Introduction

Northwestern South America is a key territory for population studies, as it constitutes a passage for both North-South and South-North migrations in the new continent. There have been recent attempts to identify how early settlements in the Colombian territory took place based on biological samples and the analysis of different molecular markers (Casas-Vargas, et al., 2017; Díaz-Matallana, et al., 2016; Noguera-Santamaría, et al., 2015; Noguera, et al., 2014; Casas-Vargas, et al., 2011; Jara, et al., 2010; Uricoechea, et al., 2010; Keyeux & Usaquén, 2008; Briceño, 2003; Keyeux, et al., 2002; Noguera & Bernal, 2010).

Studies on pre-Hispanic populations (Casas-Vargas, et al., 2011; Silva, et al., 2008) have allowed an initial approach to human genetic variability in Colombia. However, although various archeological contexts have been identified in the Colombian north coast (Angulo-Valdés, 1951; 1981; 1983; 1988; Ramos & Archila, 2008; Rivera-Sandoval, 2018; Rojas-Sepúlveda & Martín, 2015), little is known about their genetic variability within the pre-Hispanic Caribbean region.

One of the most thoroughly studied areas in the Colombian Caribbean coast is the archaeological site of Malambo, near the Magdalena River. Its inhabitants settled and adapted to environmental determinants in Lower Magdalena around 3070±200 years B.P. Their crops and the use of water resources such as rivers and lakes can be deducted from the remains of typical archaeofauna in these ecosystems. This type of sustenance is associated with well-known ceramic structures in western Venezuela and the Orinoco River valley (Angulo, 1981, Langebaek, 1987, Meneses & Gordonés, 2005). However, there are some questions regarding the Malambo timeline and its associations with other archaeological sites in the region, some of which seem to differ from the periods proposed by Angulo (Langebaek, et al., 1998, Langebaek & Dever, 2000). In fact, it has been suggested that Malambo's excavations belong to different occupations, some of which were interpreted as a single establishment (Langebaek & Dever, 2000), as verified by the detailed analysis of ceramics reported on the site since the incised modeling style known as the Malambo tradition is predominantly located in the deepest strata while the ceramics located in the superficial layers show similar characteristics to those of the indigenous settlements in the late period linked to the Malibú tradition between the 13th and 16th centuries (Rivera-Sandoval, 2018).

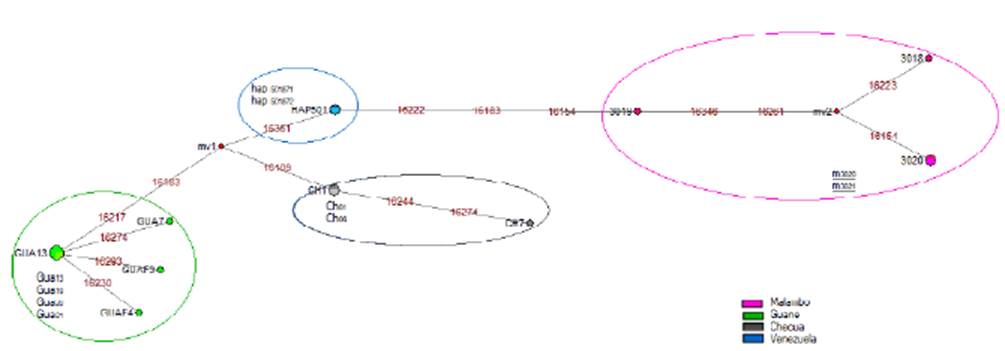

One aspect to consider about Malambo, besides its deep history, is its relationship with other contemporary communities established in distant regions and with those occupying the region at different times. Genetic analysis can be very helpful in order to answer these questions. Previous works have defined specific American lineages (A2, B2, C1b, 21, C1c, C1c, C1d, D1, D4h3) described as founding lineages (Figure 1), as well as the sub-haplogroups found in North, Central, and South America (A2a, A2b, C4c, D2A, D3, D4E1, X2a, X2g, A2ad, A2af1 B2i2, B2J, B2K, B2L C1b13, DIG, D1J) (Tamm, et al., 2007; Perego, et al., 2009; De Saint Pierre, et al., 2012; Gómez-Carballa, et al., 2012; Romero-Murillo, 2016). In this study, we selected a sample of four individuals from the Malambo site excavated by Angulo (1981): two middle-aged adults, one young adult, and one subadult. We analyzed and compared mitochondrial DNA with previous results in America (Tamm, et al., 2007; Achilli, et al., 2008; Fagundes, et al., 2008; Perego, et al., 2009) to reconstruct population dynamics of ancient and contemporary communities.

Materials and methods

Human bone remains

We analyzed human remains associated with four individuals of the Pre-Colombian population of Malambo (part of the MAPUKA Museum collection at Universidad del Norte in Barranquilla), specifically, three (3) dental samples corresponding to premolars in the adults and a sample of the costal arches from the sub-adult individual (Table 1). Despite being a reduced sample, it provided new data on the genetic affiliation of the ancient populations in the Colombian Caribbean that we expect to expand with new analyses in the future. The samples were processed and analyzed according to the existing legal protocols concerning archeological heritage as established by the Instituto Colombiano de Antropologia e Historia (ICAHN) under the intervention license # 4977.

Authenticity criteria for Pre- Colombian DNA

To ensure the authenticity and fidelity of the genetic results, we adopted the criteria suggested by Cooper & Poinar (2000), i.e.: 1) Availability of a laboratory exclusive for this type of analysis (Instituto de Genética Humana-IGH at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá) and preparation of an independent pre-PCR laboratory in a separated area (first floor) in the IGH building to avoid contamination of pre-Hispanic and present samples; 2) amplification of negative and positive control groups; 3) sequencing of the same sample several times to confirm results; 4) availability of another specific laboratory for DNA analysis (at Universidad de la Sabana in Chía) to make independent replicas of selected samples; 5) strict aseptic conditions using disposable materials (coats, gloves, and masks). Additionally, each one of the areas and materials was irradiated with UV light before and after each procedure; 6) all investigators involved in the molecular study were typed for their mtDNA.

Sample preparation and DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing

Ancient DNA extraction (aDNA) in bones and teeth. To avoid the presence of PCR inhibitors we used the following protocol for aDNA extraction: 1) Cleansing of bone or teeth was performed without pulverizing (scrapping of the sample by the external surface, 1.5% sodium hypochlorite immersion for five minutes, four to five 5-minute washes with ultrapure water type 1, and, finally, a 5-minute exposure to ultraviolet light). This standardized protocol was based on previously published recommendations (Bolnick, et al., 2012; Korlevic, et al., 2015) 2); we used K proteinase (12.5 mg/mL) for bone digestion, SDS 10%, and EDTA 0.5m.; 3) and left overnight for 72 hours. We used the salting-out method previously described and standardized by our group; 4) DNA was purified with QIAquick PCR Purification Kit.

DNA amplification and sequencing. We designed four pairs of overlapping primers and used them so that the whole mtDNA hypervariable 1 was covered; we obtained fragments of approximately 150-180 bp in each reaction. We used primers np 15986-16174, np 16105-16256, np 16194-16360, and np 16261-16429 (Table 2). DNA was amplified utilizing a DNA polymerase master mix (Qiagen) containing 1.5 mM of MgCl2, 200 uM of each dNTP, 2.5 units of Taq-DNA-polymerase, and 1x Qiagen PCR Buffer. Subsequently, 0.3 uM of each primer were added to each sample. The PCR products were visualized in 2% agarose gel, stained with GelRed® (Biotium), and sequenced in the Applied Biosystems® sequencer 3130.

Table 2 Primer sequences in the present study

| Target region | Primer | Sequence (5'-3') | Annealing temperature | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control region 1 | L 15,986 | GCA CCC AAA GCT AAG ATT CTA ATT T | 61.3°C | Present |

| 16,011-6,131 | H 16,174 | CAG GTG GTC AAG TAT TTA TGG T | study | |

| Control region 2 | L 16,105 | TGC CAG CCA CCA TGA ATA TTG TAC | 58°C | Present |

| 16,127-6,229 | H 16,256 | TGC CAG CCA CCA TGA ATA TTG TAC | study | |

| Control region 3 | L 16,194 | ATG CTT ACA AGC AAG TAC AGC AA | 62.4°C | |

| 16,194-6,360 | H 16,360 | GAG AAG GGA TTT GAG TGT AAT GTG | Kemp, et | |

| Control region 4 | L 16,261 | CCT CAC CCA CTA GGA TAC CAA CAA | 62.4°C | al, 2007 |

| 16,261-16,429 | H 16,429 | GCG GGA TAT TGA TTT CAC GGA | ||

| Haplogrup B (9-pb deletion) | L 8,196 | ACA GTT TCA TGC CCA TCG TC | 55°C | Present study |

Data analysis

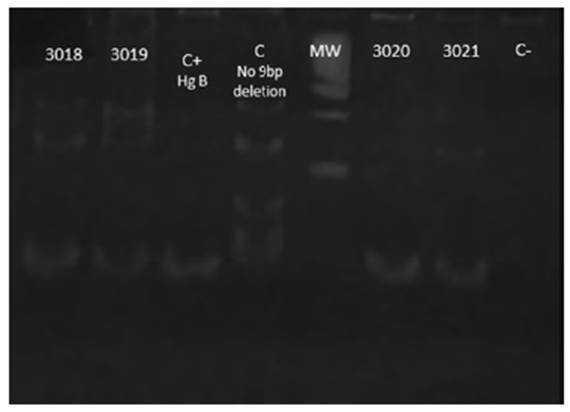

For the alignment of sequences, we used the CLC Main Workbench (Qiagen). The hyper-variable region (HVR-I) nucleotides were aligned with a consensus sequence (Cambridge Reference Sequence -CRS-). We found the G16361A mutation recently described and confirmed in haplogroup B and sub-haplogroup B2j (Gómez-Carballa, et al., 2012). We confirmed these results using restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis with the HaeIII enzyme to identify the intergenic 9-bp deletion in the COII/tRNA(Lys) as previously reported for this haplogroup. Fragments were visualized in polyacrylamide gel at 45 volts for 3 hours (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Mitochondrial DNA restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) for haplogroup B in Malambo individuals 3018, 3019, 3020, and 3021

We calculated the frequency of the haplogroup obtained by direct count. The genetic diversity was calculated based on the variant frequency: Ae= n/(n-1)= 1-Σpi2, where pi is the frequency of each allele (haplogroup) and n the size of the sample. Using the Arlequin 3.5.2 software, we analyzed the samples at intra- and inter-population levels by calculating their corresponding F st (Excoffier, et al., 2005) to estimate the genetic distances. We analyzed the phylogenetic networks of pre-Colombian mtDNA sequences obtained from the literature using a median-joining algorithm (NJ).

Intrapopulation analysis. For the assignment of the mitochondrial haplogroups, we compared the DNA sequences with the CRS reference sequence and determined the specific polymorphisms for each American-Indian haplogroup according to Torroni, et al. (1992).

Interpopulation analysis. For this analysis, we compared genetic data obtained from present and antique populations both in Colombia and in America. Then, a phylogenetic reconstruction was performed based in the genetic distances between haplogroups applying the Tamura and Nei Method (1993). Reduced Median Networks were established to determine the genetic relationship between haplogroups found in this study and other populations, as calculated and distributed by the Network 5.0 program. (Figure 1).

Results

Mitochondrial haplogroup identification

We obtained high-quality DNA from four pre-Hispanic samples belonging to Malambo human remains and we identified a single haplogroup in all of them: haplogroup B2.

This haplogroup, together with haplogroups A, C, and D, is one of the founding genetic lineages in America and can be linked to the coastal North-South peopling of the Pacific Coast. This route has been associated with the first step of the integrated multi-step migration model of the early peopling process of Northeastern South America (Neves, et al., 2005; Wang, et al., 2007; Reich, et al., 2012; Rasmussen, et al., 2014; Raghavan, et al., 2015; Skoglund, et al., 2015; Díaz-Matallana, et al., 2016; Llamas, et al., 2016; Lindo, et al., 2017; Moreno-Mayar, et al., 2018; Scheib, et al., 2018). It is thought that these human groups advanced in a West-East direction from the Pacific Ocean and arrived to the inter-Andean valleys possibly locating themselves on the borders of the Magdalena and Cauca Rivers before continuing their migratory route (Díaz-Matallana, et al., 2016). The model may correspond to the Malambo settlement according to the genetic closeness shown by this Colombian Caribbean population and other early groups from the central high plains of present-day Colombia, such as the Checua, site dated 8200±10 years B. P. (Groot, 1992) (Figure 1).

Haplogroup B2 is one of the most widely distributed haplogroups in the continent nowadays, which suggests genetic continuity since the Paleo-Americans up to the contemporary mestizo communities (Díaz-Matallana, et al., 2016). Nevertheless, our results show a high genetic distance of 0.37258 between the Malambo and the Checua that may be due to the presence of specific sub-haplogroup B2j in all four Malambo samples, all associated to the mutation G16361A. This same mutation was recently described in an individual from Venezuela, far from the Checua and relatively near the Malambo (Gómez-Carballa, et al., 2012).

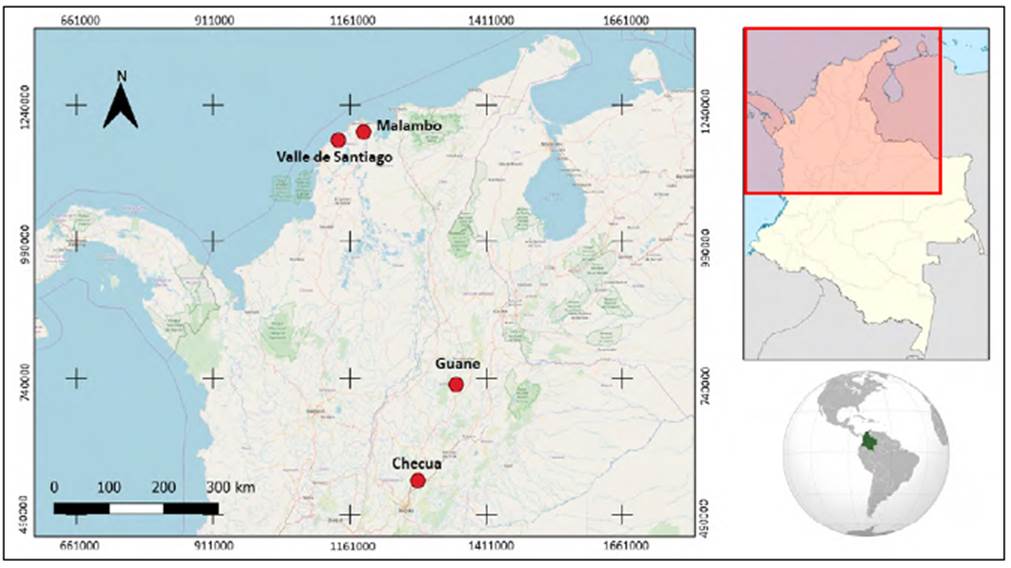

Georeferencing

We used Google Maps to draw a map using the longitude and latitude references for each location where the samples were reported (Figure 3).

Discussion

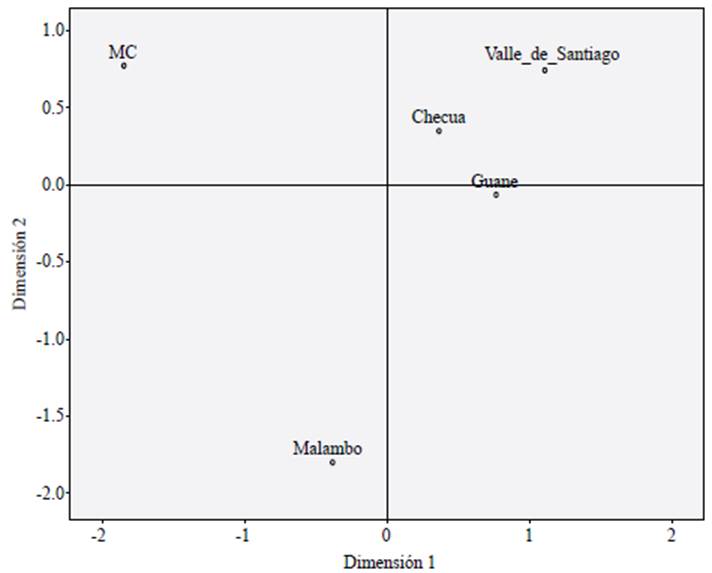

Lower Magdalena is a geographically and culturally diverse region. To determine whether such diversity could be associated with the biological composition of the ancient human groups that settled in this region of the Caribbean, we carried out a genetic analysis of available bone and teeth remains. Based on our preliminary results with ancient DNA (aDNA), we found no evidence of population variability among the indigenous groups that settled in this region compared to other contemporary communities. Using bioarcheological and genetic results, we conducted a multi-variant analysis integrating the different data to correlate each result. We used the SPSS version 1.8 software for the analysis and generated a genetic distance matrix based on the Fst data; we also performing a principal component analysis (PCA) using haplogroup frequencies obtained upon the comparison of data from the present study with previously reported archeological populations of Colombia. For comparative purposes, we chose samples from Checua, Guane, and Valle de Santiago sites: the Checua are one of the oldest populations of Colombia while the Guane correspond to an indigenous group who inhabited the municipalities of Los Santos, Jordán, and Cabrera in the Northwestern department of Santander and the Valle de Santiago, a native population of the Lower Magdalena region (Figure 4,Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 4 Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Malambo, Valle de Santiago, Guane, and Checua communities. Individual MC corresponds to the experimental researcher of the present work.

Table 3 Genetic distance matrix based on FST data from pre-Columbian individuals belonging to Checua, Guane, and Malambo populations

| CHECUA | GUANE | MALAMBO | CONTROL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Checua | 0 | 0,11141 | 0,37258 | 0,50036 |

| Guane | 0,11141 | 0 | 0,36727 | 0,6237 |

| Malambo | 0,37258 | 0,36727 | 0 | 1 |

| Control | 0,05292 | 0,07636 | 1,00000 | 0 |

Table 4 Genetic mutations in pre-Columbian Malambo and contemporary individuals. MCN corresponds to the experimental researcher of the present work.

| Population | Sample | 16069 | 16126 | 16145 | 16154 | 16166 16167 16172 | 16183 | 16189 16217 16222 | 16223 | 16261 | 16346 | 16361 | Haplotype Haplogroup | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Cambridge | C | T | G | T | A A T | A | TTC | C | C | G | G | rCRS | H2a2al |

| 3018 | 154A | 222T | 223T | 261T | 346C | 361A | HI | B2j | ||||||

| Malambo | 3019 | 154A | 222T | 261C | 346G | 361A | H2 | B2j | ||||||

| 3020 | 223C | 261T | 346C | 361A | H3 | B2j | ||||||||

| 3021 | 222T | 261T | 346C | 361A | H4 | B2j | ||||||||

| Caracas/ Venezuela | HAP71 | 183C | H5 | B2j | ||||||||||

| Pueblo llano/ Venezuela | HAP72 | 183C | H5 | B2j | ||||||||||

| Researcher | MCN | 69T | 126C | 145A | 172C | 222T | 261T | 346A | HJ | Jlbla | ||||

Human groups established in Malambo around 3120 years B.P. started a new model of settlement in the region and promoted horticulture including tuber cultigens such as cassava (Angulo, 1981; Groot, 1989). From an archeological perspective, this subsistence pattern, as well as the pottery style identified in Malambo, have been closely related to populations in the Venezuelan Orinoquia, specifically the Barrancoid series (Angulo, 1981; Langebaek, 1987; Langebaek & Dever, 2000; Meneses & Godonés, 2005; Sanoja, 1978). The results regarding the genetic distances at an interpopulation level seem to confirm the relationship proposed from the archeological perspective, specifically with the identification of sub-haplogroup B2j, which has been reported among present Venezuelan populations and indicates that this sub-haplogroup could be traced back in Northern South America up to approximately 3900 years B.P. (Gómez-Carballa, et al., 2012). This date approaches the earliest occupation of the archeological site of Malambo, i.e., 3070±200 years B.P. (Angulo, 1981).

A predominance of the founding American mitochondrial haplogroups (A-D) has been reported in Colombia (Silva, et al., 2008; Casas-Vargas, et al., 2011; Noguera, et al., 2015; Díaz-Matallana, et al., 2016; Casas-Vargas, et al., 2017). In contemporary populations, the most frequent haplogroup is A (48.3%), one of the most common in Mesoamerica, which supports those models proposing early Chibchan linguistic group migrations from Mesoamerica to South America. Haplogroup C (28.4%) has also been found in previous studies and, less frequently, haplogroups B (16%) and D (6%) (Noguera, et al., 2015). Population dynamics among the Paleo-Colombian populations has been somewhat different: in the Cundi-Boyacense high plains, a predominance of haplogroups A and B has been reported (Casas-Vargas, et al., 2017; Silva, et al., 2008), as well as a higher frequency of haplogroup B in different Colombian regions with the continued presence of diverse haplogroups such as the B2 and the C1 in the Andes region (Díaz-Matallana, et al., 2016), Norte de Santander (Romero-Murillo, 2016), and Santander (Casas-Vargas, et al., 2011).

We identified haplogroup B2 in all four individuals of the Malambo population. This haplogroup is widely distributed in the American continent, which has been interpreted as evidence of the genetic continuity that endures since the first settlers up to contemporary mestizo populations (Díaz-Matallana, et al., 2016). Thus, haplogroup B2 has been associated with the founding genetic lineages in the continent along with haplogroups A, C, and D, which would be supported by the integrated migration model of the early populating of northwestern South America as evidenced by genetic, geological, archeological, and anthropological findings. This model proposes that the first settlers of northern South America migrated across the coastal route of the Pacific Ocean. It is assumed that these groups moved sequential movements through the Andes in a West-East direction across the Cauca and Magdalena Rivers valleys where they found the advantage of easy feeding resources and were also used as fluvial migratory routes (Díaz-Matallana, et al, 2016). This influenced adaptation strategies and settlements in these ecosystems directly.

A specific sub-haplogroup B2j was identified in individuals from the archaeological Malambo site and also reported across the Venezuelan Caribbean northern coastline with no reference to the maternal ancestry (Gómez-Carballa, et al., 2012). The G16361A mutation present in all four individuals has been confirmed as a diagnostic mutation for this sub-haplogroup. Based on this coincidence, even with the inherent limitations of a preliminary analysis of only four pre-Columbian individuals and their comparison with only one individual in contemporary Venezuela, we can postulate both a maternal affiliation and a migration process to or from the Orinoco River valley down or up the Lower Magdalena territories. This relationship amongst pre-Hispanic populations of the Colombian Caribbean and Lower Orinoco may also be confirmed by comparing the ceramic styles identified by archeologists in Malambo (Colombia) and Barrancas (Venezuela). These sites share some stylistic designs that seem to belong to the same cultural tradition established in the Caribbean from 3070±200 years B.P. up to 1270±150 years B.P. (Angulo, 1981; Sanoja, 1978).

Sub-haplogroup B2j is characterized by T131C, A183G, C5270T, A15824T, A16166G, A16183C, G16361A, and T16519G mutations. Its coalescence age was estimated at 3.9 ky (95% C.I.: 0-7.8) and, as such, it has been considered a recent clade within the phylogenetic tree of haplogroup B (Gómez-Carballa, et al., 2012). This coalescence age coincides with the earliest occupational period reported for Malambo. Even so, the population of Malambo is differentiated from the Guane and the Checua in that it presents the specific G16361A mutation associated with the B2j sub-haplogroup identifying the Malambo as a whole separate group.

On the other hand, continuity in these sites of occupation might have been much wider than what has been registered up to this moment with an incidence in genetic relationships of the Lower Magdalena populations. Even if specific cultural tradition and lifestyle have been identified for the Malambo group, recent radiocarbon analysis in bone samples from a particular individual of this study (individual 3018) dated this individual between 1405 and 1445 A.D. [573-613 B.P.] (Rivera-Sandoval, 2018). This chronology is linked to the late period groups characterized by a very similar ceramic style as compared with the most superficial layers in Malambo (Angulo, 1981). This has also been reported in other sectors of Lower Magdalena (Angulo, 1955; 1983; 1988; Ramos & Archila, 2008; Rivera-Sandoval, 2018). These ceramics have also been associated with Malibú populations (Falchetti, 1993) differing from Malambo's incised modeling decoration but with similar technological features in the paste composition and clay temper.

Although the coincidence of the G16361A mutation corresponding to a B2j sub-haplogroup could result from an independent mutational event, the geographical proximity in northern South America of the corresponding individuals within +500 years suggests a matrilineal genetic continuity among Lower Magdalena populations. This eventual biological continuity might not necessarily be reflected on the cultural traditions represented in the type of cultural material present in the archeological archives nor in the sustenance ecosystems and resource exploitation, which during the late period were oriented to the exploitation of corn and other plants, hunting, and fishing, as well as fauna recollections associated to rivers and lakes. Genetics would thus offer new data for bioarchaeological studies in the New World, including the eventual maternal filiation and continuity of northern South American populations with the presence of genetically related individuals who underwent cultural mutations as demonstrated by their ceramic vessels.

Conclusions

Our data support the importance of aDNA contribution to archeological studies as they are complemented with further evidence to reconstruct mobility patterns and relationships between ancient pre-Hispanic groups in this region of South America. We implemented non-disruptive DNA cleansing showing a high reproducibility of results for every DNA extraction, which allowed a confident mitochondrial DNA analysis of several bone fragments.

Out of the four mitochondrial haplogroups (A, B, C, and D) previously assigned to the first settlers in America, i.e., an exclusive presence of B lineage, was determined in all four samples of the Malambo archeological site showing a strong association with a modern contemporary individual in Venezuela who shared the B2j sub-haplogroup. This preliminary finding in five individuals (four pre-Columbian Malambo and one 20th century mestizo from Venezuela) can be associated with possible migratory routes, contacts, and exchanges that could have occurred in the last 3000 years as, from a molecular genetic perspective, they adjust to the coalescence age of the corresponding mutations. However, it is necessary to integrate the genetic data with additional genetic markers in these four pre-Columbian individuals and further contextualize this information with archeological data.