Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile no.6 Bogotá Jan./Dec. 2005

Isobel Rainey de Díaz

Freelance ELT consultant, retired lecturer University of Surrey, U.K.

i.raineydediaz@ntlworld.com

This article describes and analyses the concerns of EFL secondary school teachers who do, or would like to be doing, research into their own classroom practices. The study attempts to show that, despite claims to the contrary, these concerns are still not being accounted for in mainstream TESOL. Even though EFL teachers may have been given voice within their national contexts, that voice is neither being heard nor acted upon in the dominant TESOL community. It is suggested, therefore, that until EFL teachers from non-mainstream TESOL contexts not only benefit from but also contribute to that body of knowledge which forms the bedrock of TESOL, and from which many reforms derive, this profession will continue to be hegemonic and not truly representative of a global TESOL reality.

Key words: EFL teachers, secondary school, mainstream TESOL, non-mainstream TESOL, research concerns and interests, inner and expanding circles

Se describen y analizan las áreas de investigación que interesan a aquellos profesores de inglés, nivel secundario, que hacen o quieren hacer investigación en sus propios salones de clase. Aunque en la literatura se sostiene que hoy en día se toman en cuenta los intereses de dichos profesores, este estudio intenta demostrar que éste no es el caso. Aunque dentro de contextos nacionales se ha venido cediendo 'voz' a los profesores, la comunidad dominante de TESOL no ha parecido prestarle importancia. Por lo tanto, se sugiere reflexionar sobre el siguiente hecho: mientras los profesores de inglés de contextos no-dominantes no saquen provecho, ni contribuyan a los conocimientos que forman la base de TESOL, de los cuales se derivan muchas reformas, esta profesión seguirá siendo hegemónica.

Palabras claves: Profesores de inglés como idioma extranjero, colegios secundarios, la línea dominante en TESOL, la línea no-dominante, los temas e intereses de los investigadores, el círculo interior y el círculo creciente

1. INTRODUCTION

Although this study draws on the research aspirations and actual research projects of EFL teachers in non-mainstream TESOL contexts1 in general, it concentrates on the concerns and interests of EFL secondary school teachers in particular. Several factors have influenced this choice of focus.

First, the EFL secondary school community – of both teachers and learners – is by far the largest of the TESOL communities. Although some countries, under pressure from the effects of economic globalisation, have recently made EFL compulsory at the primary school level (Colombia and Argentina, for example), this is still not the case in many other countries (Peru and Indonesia, for instance). At secondary level, on the other hand, the vast majority of learners study English, even in those countries where they can opt to study a foreign language other than English. In Argentina, for example, where learners can still choose between English and French,2 the majority still opt for English. Again, the reason mooted for the preference for EFL is that it is English – the so-called language of international communication – which is required by global market forces. As for tertiary level, while there is a similar preference among students for EFL, it is commonly acknowledged that the population of learners and, therefore, teachers at tertiary level is universally much smaller than that of the other two levels. Thus, the size of the EFL secondary school population is still by far the largest of the three main levels and, considering that this community includes countries like China, Indonesia, Brazil and Japan, it is clearly very large indeed. It is logical, therefore, that such a vast community should be of interest to all those concerned with TESOL.

Another reason for the choice of focus is that, given the size of the EFL secondary school community, it is with some urgency that mainstream TESOL needs not only to begin to listen to but also to act upon the messages which emanate from the research aspirations and projects of the teachers in this community. Unless the knowledge and research results of TESOL’s largest community are assimilated into the mainstream, it is an aberration to talk of a global TESOL reality. So far (see below), there is little evidence that this process of assimilation has actually got under way. It is hoped that this study will make a contribution, albeit modest, to redressing this problem.

My personal experience with secondary school teachers of EFL has also greatly influenced the focus of this study. In the course of many years of international travels, I have heard the refrain, “They’ve had 6 years of secondary school and these EFL learners still don’t know any English.” dozens of times and in contexts as varied as Costa Rica, Korea, Malaysia, Japan, and Taiwan. Such claims do not reflect well on the EFL secondary school teacher. Paradoxically, however, I have also found that EFL secondary school teachers, again from a wide international spectrum (Argentina, Colombia, Ecuador, Korea, Pakistan3 , Peru, Tunisia, Turkey) have figured among my most enthusiastic learners on all kinds of teacher education programmes – pre-service, in-service, and post-graduate programmes. In their willingness to acquire more knowledge, improve their practices, and contribute from their own experiences and research to the body of knowledge at the core of this profession, they have been unswervingly enthusiastic, determined and diligent. It is, in short, hard to reconcile the ‘bad press’ these teachers receive with their personae as seekers and potential generators of professional knowledge. This study seeks to throw some light on this apparent incongruity.

The study begins with a brief overview of the historical issues which, during the 1980s and 1990s, led to major changes in the orientation of traditional EFL teacher education programmes and which, in theory at least, resulted in a change of roles for and attitudes towards the practising EFL teacher in general and the EFL secondary school teacher in particular. It goes on to describe and analyse data collected from EFL secondary school teachers about their research aspirations and active interests, and to juxtapose these with those of mainstream TESOL. It concludes with a discussion of the implications of these findings for both mainstream and non-mainstream TESOL.

2. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF EFL TEACHERS AS RESEARCHERS

The view that teachers should research their own practices and, in so doing, make a contribution to the body of knowledge available for teacher education, is not new. It goes back at least as far as Dewey (1929), who claimed that this type of research was ‘a profoundly important form of educational scholarship’ (Lagemann, 1999, p.375). Between the 1930s and the 1980s, for reasons which fall outside the scope of this article (See Lagemann 1999 for one meagre attempt at documenting them), schools and colleges of education lost sight of the valuable contribution teachers could make to the scholarship of their respective subject areas. Instead, there was ‘the belief that education can be changed through changes in the curriculum’ (Marcondes, 1999, p.209). Teachers of every subject at both primary and secondary school levels and, it would appear, in most countries all over the world, followed curricula that were dictated from ‘above’, i.e. curricula which were the products of research, often exclusively theoretical, carried out by university and college lecturers whose knowledge of school reality derived either from a distant memory of the days when they had first started teaching or from something they had merely read up on in books.

In the case of EFL teachers, the situation was exacerbated by the fact that not only did the curriculum4 dictates come from ‘above’, they also came from ‘afar’. That is, most of the research which greatly influenced EFL curricula for all but the last two decades of the 20th century was generated in what Kachru (1986) and Kachru and Nelson (2001) term inner circle countries, i.e. countries, such as Canada, the USA, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, where English is spoken as the first official language5 . The results of this same research were ‘exported’, with great enthusiasm and insistence, to contexts in the expanding circle6, i.e. to countries like Brazil, Indonesia, Japan, where English is taught and learned as a foreign language. Thus, EFL teachers in what is here termed non-mainstream TESOL contexts7 were continually bombarded with knowledge from the inner circle, and in time, too, from ‘privileged’ members of the expanding circle (Germany, France, etc.). Such knowledge pertained to all aspects of their work, namely, teaching methods, syllabus types, teacher’s and learners’ roles, learner strategies and testing techniques, and came with the implicit promise that the teachers’ lot would be easier and their teaching more successful if they changed their teaching to accommodate the proposed ‘innovations’.

Often and not surprisingly, given the origins of the new ideas, the teachers’ sincere efforts to innovate were rewarded, not with the success that had been forecast by the apologists of the innovations, but with even greater failure and the ensuing despondency. “Teachers … flock to conferences and workshops, looking forward to learning different ways of doing things. They anticipate with excitement the arrival of the latest textbook and materials. Subsequently, they are sometimes disappointed and frustrated when, in the classroom, these activities and textbooks do not meet with great success.” (Musumeci, 1997, p.2).

It would be wrong, unfair and grossly inaccurate to claim that nothing good has ever come out of these very unequal power relationships between mainstream researchers and non-mainstream teachers. The results of research from the mainstream into the areas of error analysis and interlanguage (IL), for example, have served to throw much light on how foreign languages are learned/acquired, and have, therefore, contributed to a fuller understanding of the learning/acquisition processes. This, in turn, has helped teachers, among other things, to adopt more tolerant attitudes towards, and a deeper scientific understanding of learners’ errors. Similarly, pedagogical principles such as those underlying speaking activities based on the information and opinion gap have proved excellent facilitators of student oral participation, often in contexts where one of the main stumbling blocks to learner progress has been the students’ unwillingness to participate in class activities. Many of the improvements in the teaching of the skills of reading, writing and listening (use of background knowledge, the need for drafting in the writing process and the advantages of going from gist to detailed understanding) have also derived from inner circle research. Ignored for many decades, however, was the fact that much of what was imported from the mainstream was often culturally alienating, at least initially, and especially if it was abruptly imposed on unprepared and untrained learners (See Kramsch, 1993; Rainey, 2002), or it was contextually inappropriate in as much as the content of the learning experience failed to address the needs of the society in which the learning was taking place (Kramsch, 1993; Breen, 2001).

All of this has been well documented before in the works of scholars like Philippson (1992), Pennycook (1994), Holliday (1998), and Carnagaragh (1999). It is touched on again merely to explain why, when mainstream education, under the influence of Stenhouse (1975 ), began to subscribe once more to the idea that it was teachers, and not mainstream researchers, who should be the principal generators of the knowledge needed to understand and improve classroom practices, and to reform curricula, the TESOL profession began, a decade or so later, to embrace this idea with open arms (Nunan, 1989; Edge and Richards, 1993; Freeman, 1998; Richards, 1998; Wallace, 1991). It is worth pointing out, however, that more than a decade before action research became ‘fashionable’ in TESOL, two Canadian foreign language teacher educators had already claimed that “...basic research techniques are not effectively productive for generating applied knowledge. The latter must be produced by the person who is going to use it and is closest to the data, namely, the teacher himself.” (Jackobitis and Gordon, 1974, p. 249).

At any rate, in the latter part of the 20th century, action research became the new order of the day (Rainey, 2000, p.65) in TESOL education, and, since then, it has been taken as given that it is the EFL teachers who should be the originators of change in their practices and that this change should reflect the outcomes of their research into their own practices. This is the theory. In practice, Rainey (2000) reported, however, that, in an international survey, the majority of EFL secondary school teachers had never heard of action research and, of those that had, few were actually doing it or had ever done it. Of those few teachers that were doing it or had done it, most claimed that they wrote up their research but no concrete evidence of the dissemination of their research reports was forthcoming and, as Rainey pointed out, without access to the teachers’ research, it is virtually impossible for the knowledge and expertise that successful teachers have developed to foster educational reform’ (2000: 83).

Much of the literature (See Nunan, 1989; Freeman, 1998; Wallace, 1998, amongst others) leaves the reader with the impression that the research of EFL classroom teachers is done mainly for the teachers’ own benefit. Riley’s position is representative of such a view. “Teacher research provides teachers with a systematic way to examine problems or issues in their own situation and to address these problems or issues.” (2000: 24).

From what is written in the TESOL literature, reaching out beyond the confines of their individual classrooms to share their research findings would appear to be, in the theorists’ view, an option – the icing on the cake for the teacher researchers. Although there are those who encourage collaborative teacher research, the scope of the influence of such research would also appear to be somewhat restricted. Burns, for example, recognises that teacher research done collaboratively can influence school policy. “Developing critical changes in practice from the basis of teachers’ collective research on school problems would, therefore, seem a fruitful direction in which to go.” (1999: 225).

Burns also claims that, on working collaboratively with other teachers, the sense of isolation so common in this profession is reduced and the ‘research process empowers teachers by reaffirming their professional judgement and enabling them to take steps to make reflection on practice a regular part of everyday teaching’ (1999: 234). None of this is being questioned. Rather, it is being suggested here that it does not go far enough. What is missing in most of the literature is a clear acknowledgement that the results of teacher classroom research could and should benefit and be of interest to a much wider audience - to the global TESOL community because “… many case studies aimed at improving action in particular settings have yielded generally useful insights into the complexities of teaching and learning, and … many action research projects have focussed on problems and dilemmas teachers experience across a wide range and variety of educational settings.” (Elliott, 2004, p.3).

It is precisely those insights and complexities that emerge from EFL secondary school teachers’ research that are at the core of this study.

3. PROCEDURES AND METHOD

The study draws on three sources of data, collected in the following ways.

3.1 Survey

EFL secondary school teachers attending professional conferences or in-service professional development seminars, most of whom had not yet received any formal training in classroom research methods/techniques, completed a simple questionnaire where they provided some basic bio data and answered the following question: ‘If you had the necessary resources (time, training and support), which aspect/s of your teaching would you like to research?’ This question was chosen as it was assumed that the topics identified would reveal the problems and issues of concern to the teachers in their specific teaching contexts.

A list was drawn up of all the topics generated by the questionnaires; these were then coded, and classified into general topic areas (See 4: Results).

The questionnaires were answered by teachers from Argentina, Costa Rica, Spain, and Pakistan8 , as these were the communities to which I had access when I began the study. In other words, the communities were selected on a convenience basis but, fortunately, they spawned data from four continents and represented not only non-mainstream contexts but also one mainstream TESOL country, Spain (See footnote 1). As most of the teachers taught in at least two institutions, they were instructed to express their research preferences for the state/public school contexts and/or for the not-so- privileged private secondary school contexts in which they taught. (Many private schools even in non-mainstream countries are very privileged and the teaching and learning conditions reflect those of mainstream country schools; these were not the focus of this study.)

3.2 Meta-Analysis (1)

A meta-analysis was conducted of the research topics selected by EFL secondary school teachers who were doing, and who had already done, research into their own practices. In the case of the former, the topics were listed as ongoing research in the Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, September 2003 (CALJ); in the case of the latter, the topics were identified in the actual reports of their research which Colombian teachers had published in the PROFILE Journal. Although both of these sources are from the same country, this, as we will see in Discussion, is not as restricting as it may seem and may even have served to strengthen the argument in this article. Once again, all the research topics pertained to the work of teachers in state or not-very-privileged private secondary schools.

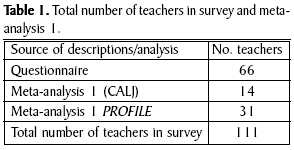

Table 1 contains details of the number of teachers involved in each of these sources of data (3.1, 3.2).

3.3 Meta-Analysis (2)

Yet another meta-analysis was conducted. This analysis focuses on the EF/SL/FL9 topics in research articles in three international journals. These journals (See 4.3) are commonly recognised by mainstream TESOL researchers as three of the journals which have most influence on the beliefs and practices of FL teaching in general and the international TESOL community in particular. The results for the three groupings (3.1, 3.2 and 3.3) were then juxtaposed to check for convergence of interests and concerns, and these results are described and analysed in 4.

3.4 Questions

Although this study does not represent a formal piece of research, the following questions served to give it a sense of direction and purpose:

• Which topic areas are the most common among the teachers/teacher researchers in the survey and in meta-analysis 1?

• What are the messages and insights which emanate from EFL secondary school teachers’ research topic preferences?

• What convergence, if any, is there between the interests of EFL secondary school teachers’ research concerns and the research concerns of mainstream TESOL?

• Why, if at all, are the research interests and concerns of secondary school teachers important, not just to the teachers themselves but to mainstream TESOL? • To what extent, if any, are these messages and insights being listened to and acted upon by the mainstream?

4. RESULTS

This section begins with a description and analyses of the survey results. The results for each subsequent source are then described, analysed and compared and contrasted with the foregoing set/s of results.

4.1 Survey

A total of 66 teachers completed the questionnaire (See Table 1 in 3.2 above): 23 from Argentina; 20 from Spain; 15 from Pakistan; and 8 from Costa Rica.

After the topics were coded, they were classified into 8 major categories/topic areas: Socio-affective/Cultural (SAC); Second language acquisition (SLA); Skills teaching (ST); Student corpora (SC), for example, written texts for error analysis, recorded texts for interlanguage studies; Grammar teaching (GTG); Language learning behaviours (LLBs); General methodology (GM); and Testing (TG). Most of the classifications are self-explanatory but here are examples of three which might not be immediately obvious.

General Methodology (GM) contrasts with formal skills teaching (ST), formal grammar teaching (GTG) and SLA concerns. For example, How can I help all my students in mixed ability classes (Argentina) was classified as GM as was How can project-based learning help EFL learners in large classes to use English meaningfully? (Pakistan)

Language Learning Behaviours (LLBs): (1) What are my students’ learning strategies and what are the teachers’ assumptions about them? (Pakistan); (2) What knowledge and behaviours do learners already have at their entry level to my school? (Pakistan)

Socio-Affective/Cultural (SAC): (1) How do feelings, like shyness, and attitudes such as a strong dislike of the FL culture, and politics affect learning and how can I reduce the negative effects? (Argentina); How can I motivate my teenage learners when they are so worried about external problems (parents’ divorce, for example)? (Argentina)

As with most classification tasks, there was occasionally some topic overlap, making classification difficult (for example, in Language Learning Behaviours above, item (2) could also have been classified under Testing). In the case of this study, however, topic classification dilemmas were few and when they did occur, the eventual classification of the topic made little difference, if any, to the overall results.

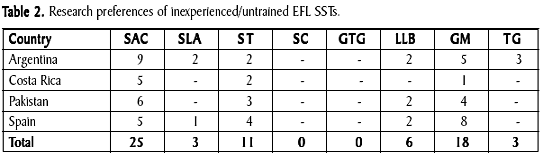

Table 2 shows the results for each country represented in the survey.

With respect to these results, several points are worth making. First, not only do socio-affective and cultural (SAC) issues receive the most interest from the group as a whole but, with the exception of Spain (the mainstream TESOL country), they are also the issues of greatest concern for each individual non-mainstream context, with 9 among the 20 Argentinean, 5 among the 8 Costa Rican, and 6 among the 15 Pakistani teachers selecting a SAC topic. Other examples of the teachers’ concerns in the area of SAC include:

(1) Is it possible to motivate my learners by integrating the teaching of English with that of the teaching of other subjects on the curriculum? (Spain)

(2) What are my students’ motivations for learning English? (Pakistan)

(3) How can I give to school tasks the social values teenagers need to cope with life outside the classroom? (Argentina)

(4) How does the very hot weather in my country (on the Caribbean Coast) affect students’ attention in class and how can we find a solution? (Costa Rica)

A second point worthy of note is that not one single teacher out of a total of 66 and from countries as far flung as Argentina and Pakistan identified the teaching of grammar as an area they would like to research. This is especially interesting in light of the voluminous literature which, in the past two decades, has come flooding out of mainstream TESOL on research into the teaching of grammar (See Poole, 2003, for an excellent summary and appraisal of this literature and of the concomitant debate). What message are these teachers conveying by not choosing GTG as one of their research topics? Are they saying that they have already sorted out their GTG problems and that they do not need to do any research into this aspect of their teaching? Or, are they simply indicating that, before researching any GTG problems they may have, they have much more pressing problems? Given the conditions under which many/most of these teachers work, the likelihood that their message is contained in the second possibility is high.

Other points could be made on the basis of this table but, as space is of the essence, there is room for only one more. Does the absence of an entry under SC (Student Corpora) indicate that teachers are not interested in the valuable data which derive from student generated data or does it simply reveal that not enough attention has been paid to, or training given in, SC in the teachers’ education programmes? Food for thought!

4.2 Meta-Analyses (1)

This analysis examines the topics chosen by two groups: trainee teachers who had just started and teacher researchers who had completed research into their teaching practices.

4.2.1 Trainee Teachers’ Choices of Research Topic

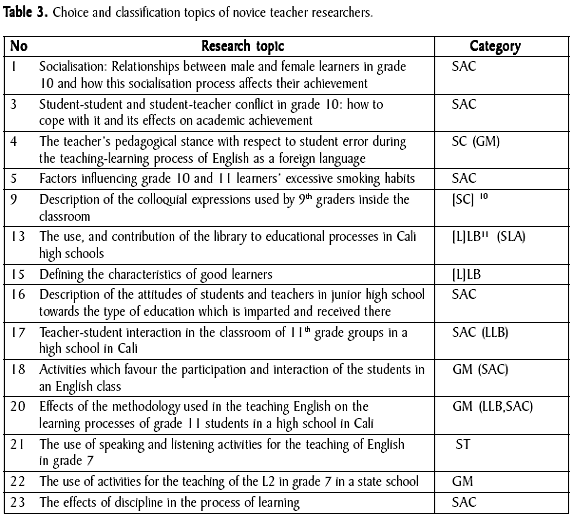

For reasons of space already commented on in 4.1 above, the first part of this analysis is limited to one article in the CALJ (Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal), namely, No 5, September, 2003. This may not seem a lot but, when it is combined with the second part of the analysis, it is sufficient. Writing in considerable, and very useful detail about how different types of research skills are integrated into the basic teacher preparation programme in the Licenciatura programme in foreign languages at the Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, Cárdenas Ramos (2003) provides in appendix 2 (pp. 42-43) a list of the topics which the EFL trainee teachers selected for their research projects, a compulsory part of the research component of the course. Even this list – of just 23 topics - is a goldmine of information for anybody who claims to have an interest in the knowledge generated by EFL teachers in non-mainstream contexts with a view to integrating such knowledge into mainstream TESOL educational reform.

Of the 23 topics provided, it is not clear in some cases whether the research is being carried out in primary or secondary school. Given my familiarity with the Colombian contexts, I have been able, in a few of these cases, to infer whether it is one or the other. I have not included those topics where my ability to infer failed me.

The topics chosen by the trainee teachers for their research at secondary school are listed in Table 3. Column 1 contains the number of the topic as it appears in Cárdenas Ramos’ original appendix. Column 2 contains the titles of the topic. Column 3 reveals the topic categorisation based on the classification procedures already applied in 4.1. Where there appears to be topic area overlap, the second and third topic areas have been placed in brackets after what would appear to be the main topic area. Given the international readership of this journal, the original topic titles have been translated from Spanish into English.

On examining these data, several features stand out. First, perhaps because the teacher researchers here are still new to both teaching and research and have not yet narrowed down their focus of interest, there is a strong tendency to focus on general, as opposed to simply EFL, teaching-learning processes. See topics 1, 3, 5, 9, 13, 16 and 23. Nevertheless, the message even in these general choices is strong and reflects that of the main message in the data in 4.1: Socio-affective and cultural (SAC) matters are of great concern to these trainee teachers. Of the seven topics of general educational interest, five (1, 3, 5, 16 and 23) are classified as SAC. Of the seven topics which appear to concentrate on EFL (4, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21, and 22), three (17, 18, 20) have a SAC or shared SAC focus. This means that out of the 14 topics, over half (eight) are SAC or SAC – related topics. Those topics which are FL-oriented and which do not have a SAC focus are also of interest. As with the teachers surveyed in 4.1, there is considerable interest in GM (General Methodology) and LLB (Language Learning Behaviours), with four topics classified in or related to both of these categories. Once again, no one has selected GTG (Grammar Teaching) as the focus of his/her research. In contrast to the teachers in the survey, however, there is some interest here in SC (Student Corpora), which leads one to wonder why the teachers in the survey appear to have no interest in SC.

4.2.2 Practising Teachers’ Choices of Topic

PROFILE Journal proved an invaluable source of data for this part of meta-analysis 1, namely, the topics selected by experienced teachers who had written up their research reports and who had had them published in PROFILE. These teachers were required to do a classroom research project as a compulsory part of a professional development course they enrolled in at the National University of Colombia, Bogotá campus. Other components of the course included language improvement and methodology updating12 . It is important to note here, however, that the teachers chose the topics for their research projects in the early stages of the professional development programme as the course director did not want their choices to be conditioned by the contents of the other components, especially the methodology updating. In other words, she wanted the teachers to identify a problem they had before they came to the course as this, she believed, revealed an immediate and real need. Had they made the choice when the course was in full swing, they might have been tempted to choose topics they were attracted to in the methodology updating component, and this would not necessarily have reflected their most urgent needs.

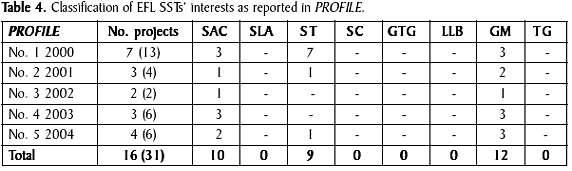

Five issues of PROFILE (No.1, 2000; No. 2, 2001; No. 3, 2002; No. 4, 2003; No. 5, 2004) were used in this analysis and are summarised in Table 4. The same coding and categorising procedures described in 4.1 and illustrated in Tables 2 and 3 were applied here, too. First, however, it is important to point out that some of the teachers in this particular professional development course did their research collaboratively. Table 4 contains, therefore, an extra column (column 2), which indicates the total number of projects reported in the corresponding issue of PROFILE and in brackets the total number of teachers undertaking the projects. The focus of interest in this study is, however, the number of teachers interested in a given topic area so the discussion will concentrate not on the number of projects but on the number of teachers.

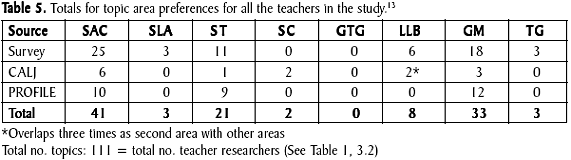

Unlike the other two sources of data, the number of teachers interested in GM (12) in terms of the Profile reports is higher than the number interested in SAC although SAC and ST follow closely behind GM with 10 and 9 respectively. Nevertheless, if the results for all three sources are computed, the overall results reveal that, among the teachers in this study, there is a greater number interested in SAC topics than in any of the other topics. See Table 5.

The scope of the interests and concerns of the secondary school teachers who wrote up their reports in PROFILE also merits some comment. In contrast to the teachers in the survey and the trainee teachers in CALJ, as many as five of the topic areas – SLA (Second Language Acquisition), SC (Student Corpora), GTG (Grammar Teaching), LLB (Language Learning Behaviours), TG (Testing) receive zero interest among the Profile teachers (See Table 4); thus, this group of teachers oncentrates intensively on GM, SAC and ST. Clearly, more research in the form perhaps of group interviews needs to be carried out to see if the teachers themselves can explain why the scope of their interests differs considerably from that of the other two. Once more, however, it is quite remarkable that, like the other two groups, this group did not choose to research GTG and, like the survey group, there is no apparent interest in SC. Part of the mystery surrounding the apparent absence of interest in GTG may reside in the fact that some of the teacher researchers in this study integrate their grammar teaching with other course components, preferring to deal with it, for example, within speaking activities. Even this, however, is, or should be, a source of interest to mainstream TESOL. At any rate, probing the reasons for this very surprising result requires further research.

4.3 Meta-Analysis (2)

TESOL Quarterly (TQ), Applied Linguistics (AL), and Language Learning (LL) were identified as three of the journals which most influence change and innovation in ES/FL and FL teaching and learning. It is not being claimed here that they are the only influence but their influence is strong. These journals are commonly rated as ‘prestigious’ or ‘blue chip’ journals and are referenced extensively in post-graduate teacher development courses in mainstream contexts. They claim to have a special interest in reporting the results of research into all aspects of TESOL and other FL teaching and learning and this is another reason why they were selected for this study; for this same reason, non-research oriented journals, ELTJ for instance, were not selected.

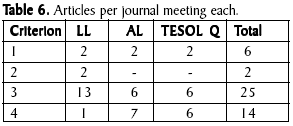

First, a tally was taken of all the articles in these journals for the years 2000, and 2001 and for one issue in 200514 which were relevant to research into and/or debates about the teaching of foreign/second languages (any foreign/second language). Out of a total of 118 articles, 86 met this general criterion. (The articles for one issue of LL were not included as that particular issue had not been published in hard copy form and at the time of doing this research the electronic copy was not available.)

Since the present discussion is specifically concerned with the teaching of EFL at secondary school level in non-mainstream contexts, the 86 articles were further narrowed down by applying the following criteria:

• Criterion 1: The article reports a formal research project which was carried out in an EFL context in non-mainstream contexts at secondary school level.

• Criterion 2: The article reports a formal research project which was carried out in an EFL context (any EFL context, not just non-mainstream) but in contrasting venues: secondary school and at least one other. (Some articles compared and contrasted vocabulary acquisition in secondary school with vocabulary acquisition at university level, for example)

• Criterion 3: The research was carried out in a non-EFL context and at a level other than secondary school but the research focused on the teaching of English (ESL, for example) and the results could be generalised, to varying degrees, to secondary school level in non-mainstream EFL contexts.

• Criterion 4: The article did not report a formal research project but discussed aspects of research and TESOL: Applied linguistics of some relevance to the present discussion.

Out of the 86 articles which met the general criterion, 47 met one or other of these four criteria. Table 6 illustrates the number of articles from each journal which met each criterion.

Two things stand out in this table: in a total of 47 articles a mere 6 were exclusively concerned with EFL at secondary school level in non-mainstream contexts, and if this is seen in the light of the total number of articles dealing with FL teaching in general, it is even worse – only 6 out of 86; out of the 47 articles meeting one of the four criteria, as many as 25 met criterion 3, that is, the research was not directly concerned with secondary school teaching; nor was it conducted in an EFL context, but the results could be generalised, to varying degrees, to such contexts. That so little research into what is the largest community of teachers and learners in the entire TESOL profession (See the discussion about the size of non-mainstream contexts in the Introduction to this article) is reported in these journals is most disconcerting and reveals an enduring and strong bias in mainstream TESOL towards educational levels other than the level with the largest community – and it would seem logical to assume the community with the greatest needs. If so little is reported in mainstream TESOL of what constitutes the reality of such a large community, it is not altogether surprising that there are misconceptions about what can be expected of learners when they complete their high school studies (See discussion in paragraph 4 of the Introduction). It may well be that, irrespective of the very different teaching and learning conditions, these learners are expected to meet the same objectives as those learners whose contexts are researched and reported.

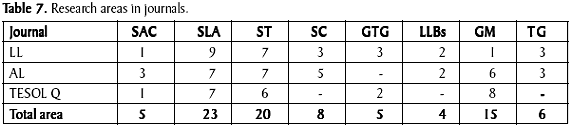

A further analysis was conducted of the articles in the journals. This time, all 86 articles were analysed for the topic areas researched or debated, applying the same procedures and classification as in 4.1 and 4.2. There were two reasons for analysing all 86 articles. First, although some dealt with the teaching of FL other than English (Dutch, Spanish, for example), they reported results and insights of some interest to all FL teaching and learning. Second, on including all 86, the number of articles was not as out of line with the total number of topic areas for 4.1 and 4.2 - 111. This, it is hoped, made the comparison fairer and more evenly balanced.

Table 7 contains the results of the classification for the 86 articles in the three mainstream journals.

Out of the 86 articles, as few as 5, that is, 5.8% were classified under SAC (Socio-affective/cultural). In contrast, as many as 41 out of 111, that is, 36.9% were classified as SAC for the results of the EFL secondary school teachers in non-mainstream contexts (See Table 5). The difference is enormous and is revelatory of the equally enormous chasm between the knowledge mainstream TESOL offers and the knowledge the EFL secondary school teachers in this study appear to be indicating they need. More importantly, the teachers in the meta-analysis are actually engaged in the relevant research and are, therefore, in a position to contribute their knowledge to the mainstream.

Another major contrast lies in the strong interest in these journals in SLA, 23 of the 86 articles, that is, 26.7% as compared with only 3 out of 111, that is 2.7%, among the teachers’ topics. Like other differences commented on above, these data require further inquiry to arrive at some possible explanation. Here it is enough to note that these marked differences exist.

Not so marked but still substantial is the GM (General Methodology) difference; whereas for the teachers it represents 29.7% (33 out of 111) of their topic area interests, it is much less for the journal articles – just 17.44% (15 out of 86).

Two other minor contrasts are worthy of note. Although in the journals only 8 articles (9.3%) are concerned with SC (Student Corpora), the apparent interest in/need for this research is even lower in the teachers’ data – 0.9% (1 out of 111).

Also worthy of mention are the areas with some convergence; for example, 18.9% (21 out of 111) of the teachers’ projects focussed on ST (Skills Teaching) as did 23% (23 out of 86) of the journal articles. Clearly, ST is an area where there is some common interest and potential for mutual support and learning but again further analysis is required to find out if the convergence pertains to the same skills.

Surprisingly, even the journal topics reveal little apparent concern for GTG (just 5 out of 86) but at least this is more than in the teachers’ topics – 0 out of 111. Equally surprising is the result for TG (Testing), just 3 out of 111 in the case of the teachers, and slightly more, 6 out of 86 in the journals. This datum may derive from the fact that there are mainstream journals which are devoted exclusively to testing. At any rate, it is just as important to explore further not only the research topics of interest to EFL secondary school teachers but also those which would appear not to be of interest to them.

5. DISCUSSION

From the data described and analysed above, it would seem fair to claim that, as far as this study goes, there are more differences than areas of common interest between the research interests and concerns of non-mainstream EFL secondary school teachers and mainstream TESOL.

Particularly worrying are the major differences, especially those with respect to SAC, greatly favoured by the teachers and virtually ignored in the journals, and SLA, favoured in the journals but virtually ignored by the teachers. Among other possible messages in these data, one would appear to be urgent: mainstream TESOL research needs to be more in touch with the socio-affective and cultural aspects of the EFL secondary school classroom. While it is not, it is failing to cater to the needs of the largest community of teachers and learners in global TESOL – EFL secondary school teachers who work in non-mainstream contexts.

This, however, is not the only message. In their determination to address the issues and problems they have with respect to SAC, some of the Colombian teachers in this research have actually undertaken or are currently undertaking the corresponding research. Their message to mainstream TESOL is not only that SAC is important but that the findings of their research are invaluable - and available. They are out there in journals for mainstream TESOL to read about, to assimilate into their teacher education programmes, and to recycle in their international journals. It could be argued that the research done by the Colombian teachers is too context specific to be of global interest but this research shows that, among the teachers in the international survey and the Colombian researchers, there is a convergence of interest; SAC is the area of greatest concern. For this reason alone, it was in fact good – fortuitously so, perhaps – to compare the concerns of teachers in one non-mainstream context with those of teachers in several other non-mainstream contexts.

Yet another message is that it is time that EFL teacher researchers from the biggest teacher-student community in this profession were offered the re-active listening ear they so badly need and deserve because ‘nothing ever really gets said until it is listened to’ and while these teachers are not listened to, it is, as commented on earlier, a nonsense to talk about ‘giving voice to teachers’ or of ‘a global TESOL community’. For such a community to exist, it must have at its core not only a knowledge base which is truly global in character but a willingness to recognise and instigate the reform and change which derive from that knowledge. “Educational researchers in the academy can collaborate with an educational agent by adopting their practical standpoint as though they were in the action context. Educational action research need not be exclusively practitioner research. The fact that it is so often construed as such by educational researchers suggests that they are viewing it as a low level a-theoretical activity from an intellectual standpoint.” (Elliott, 2004, p. 23).

That none of these 111 non-mainstream context secondary school researchers identified GTG as an area for research represents yet another energetic message: They would appear to have more pressing problems.

In sum, the evidence from this study would seem to indicate that, despite much talk and text to the contrary, the knowledge base of mainstream TESOL continues to be hegemonic and still does not reflect the needs or mirror the realities of grassroots EFL educational agents.

6. CONCLUSION

This study is not without its flaws, not least among them the subjective nature of criteria 3 and 4 applied to the 86 journal articles in 4.3. Also, there was a need to break down the topics under GM (general methodology) and ST (skills teaching) to check for convergence, or lack of it, within the subtopics of these major categories. It would have been desirable, too, to report the data for the journals for the years 2002-2004 but lack of space made that impossible. It is hoped that the message in the following concluding comments will far outweigh the impact of any minor technical inadequacies.

Every year thousands of teachers in inner circle countries and thousands of teachers from non-mainstream contexts who do post-graduate studies in the same inner circle countries are trained/educated in TESOL at inner circle universities: their staple diet is still the knowledge derived from mainstream TESOL research and that knowledge is incomplete – witness the results for the journals in this study. It still does not account for the realities of the largest community in this profession. Many inner-circle ‘trained and enlightened’ teachers travel or return to non-mainstream contexts to teach and do research, applying what they have learned in the inner circle courses, thereby perpetuating the gulf between what non-mainstream teachers believe they need and what the mainstream says they need.

Some confident and competent educators like the Colombians in this study, although no doubt there are others across the globe, resolve this problem by going about the business of adjusting what they have learned to the needs of their reality, dismissing any overbearing influence from the mainstream while generating their own pertinent knowledge. These are healthy independent attitudes and it would behove the international community to keep abreast with developments like these in Colombia and other non-mainstream contexts. Nevertheless, mainstream TESOL is missing out if what these researchers do/achieve is not just applauded but also integrated into the mainstream expertise. For years, TESOL has come to TEFL bearing, at times, dubious gifts of pedagogical enlightenment. Now, it is time for TEFL to be brought to TESOL with real truths which can be added to what should be a rich and resilient mosaic of global knowledge.

While it continues to despatch, to non-mainstream contexts, teachers with mainly or exclusively mainstream knowledge – teachers who are, therefore, not fully prepared for all the tasks they are to undertake – the needs, concerns and problems of literally millions of teachers and learners in those contexts will neither be understood nor resolved and mainstream TESOL researchers and non-mainstream EFL secondary school teacher researchers, together with their respective findings, will continue to be what they have always been - ships passing in the night.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Isobel Rainey de Díaz has worked for many years as a teacher, teacher educator, and lecturer in Applied Linguistics in Europe (England, Italy, Spain), South America (Argentina, Colombia, Peru), and the Middle and Far East (The United Arab Emirates, Japan, Korea, Pakistan). Her main research interests include: the priorities and concerns of the secondary school EFL teacher-researcher working in non-mainstream TESOL contexts; textbook design, in particular the organisation and dynamics of textbook writing teams, and the processes involved in selecting textbook themes; and the challenges facing and characteristics of the less successful language learner. Before retiring, she was a lecturer in Applied Linguistics: TESOL at the University of Surrey, Guildford, England. In retirement, she works as a freelance consultant in the areas of EFL teacher development, EFL textbook writing and intercultural communication.

1 Mainstream TESOL contexts are taken here to mean inner circle countries (See paragraph 2 of 2) like Canada, the US, Australia, the UK, Ireland, and influential countries from the expanding circle (see same paragraph of 2) like Germany, France, Sweden, which have traditionally been the main sources of innovations and reform in TESOL, and of that body of knowledge which is regarded as holding the key to successful foreign and second language teaching and learning. Non-mainstream TESOL countries are all the other countries in the expanding circle.

2 This information was provided by my colleague Lucrecia d’Andrade de Miranda of the National University of Tucuman, Argentina.

3 Although English is officially a second language in Pakistan, there are many large communities for whom it is a foreign language.

4 Curriculum and curricula in this study are to be understood as the entire FL programme, including approach, view of language, aims, objectives, methods, methodology, syllabus, and materials.

5 English is taught as a first, second and foreign language in these countries but the foreign language communities are transient and very small compared to the communities of the expanding circle.

6 The second circle, the outer circle, falls outside the scope of this discussion. According to Kachru, it is made up of those countries where English is officially recognised as a second language.

7See Footnote 1.

8 See footnote 3.

9 There were so few articles about EFL that the study had to be widened to include those ESL and FL topics which could throw some light on EFL (See 4.3).

10 Not clear whether the colloquialisms are in L1 or the FL or both; hence the square brackets

11 In this case, square brackets indicate that the trainee teacher researchers appear to be focussing on learning behaviours in general and not just on language learning behaviours.

12 I am grateful to Prof. Melba Libia Cárdenas, Director of the Teacher Development programmes at the National University, Bogotá campus, for providing me with this information.

13 Data used from Table 2 for this table have taken into account only one topic area per teacher. In those cases where there is topic overlap, only the first area has been accounted for here.

14 These data were collected for a paper read at a keynote address at KORTESOL in October 2001. The audience was so receptive that I decided to recycle them here, but to include also an analysis of the articles in one 2005 issue for each journal to see if any significant change of focus in the research interests of the journals had taken place.

REFERENCES

Breen, M. (2001). The Social Context for Language Learning: A Neglected Situation. In C.N. Candlin & N. Mercer (Eds.), English language teaching in its social context (pp. 122-144). London and New York: Routledge in association with Macquarie University and The Open University. [ Links ]

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Carnagarajah, A. S. (1999). Resisting linguistic imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, R. (2003). Developing reflective and investigative skills in teacher preparation programs: The design and implementation of the classroom research component at the foreign language program of Universidad de Valle. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 22-40. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. (1929). The sources of a science of education. New York: Liveright. [ Links ]

Edge, J. and Richards, K. (Eds.). (1993). Teachers develop teachers research. Papers on classroom research and teacher development. Oxford: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Elliott, J. (2004). The struggle to redefine the relationship between 'knowledge' and 'action' in the academy and society: Some reflections on action research in the light of the work of John Macmurray. Educar 34, 11-26. [ Links ]

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing teacher research. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers. [ Links ]

Holliday, A. (1998). Appropriate methodologies and social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Jakobovits, L. and Gordon, B. (1974). The context of foreign language teaching. Rowley, Mass: Newbury House. [ Links ]

Kachru, B. (1986). The alchemy of English. The spread function and models of non-native English. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [ Links ]

Kachru, B. and Nelson, C.L. (2001). World Englishes. In A. Burns and C. Coffin (Eds.), Analysing English in a global context: A reader (pp. 9-25). London and New York: Routledge in association with Macquarie University and The Open University. [ Links ]

Kramsch, C. (1993). Content and culture in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lagemannn, E. C. (1999). Whither schools of education? Whither education research? Journal of Teacher Education, 50, 373-376. [ Links ]

Marcondes, M. (1999). Teacher education in Brazil. Journal of Education for Teaching, 25, 203-213. [ Links ]

Musumeci, D. (1997) Breaking tradition: An exploration of the historical relationship between theory and practice in second language teaching. USA: MCGraw Hill Companies. [ Links ]

Nunan, D. (1989). Understanding language classrooms. A guide for teacher-initiated action. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Pennycook, A. (1994). The cultural politics of English as an international language. Harlow: Longman. [ Links ]

Phillippson, R. (1992). Linguistic imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Poole, A. (2003). New labels for old problems: Grammar in communicative language teaching. PROFILE Issues in Teachers´ Professional Development, 4, 18-24. [ Links ]

Rainey, I. (2002). Lessons from the less successful language learner. SPELT, 17 (2), 1-14. [ Links ]

Rainey, I. (2000). Action research and the EFL practitioner: Time to take stock. Educational Action Research: An International Journal, 8 (1), 65-92. [ Links ]

Richards, J. C. (1998). Teaching in action: Case studies from second language classroom. Alexandria, VA: TESOL. [ Links ]

Riley, K. (2000). Teachers as researchers. SPELT, 14 (3), 24-27. [ Links ]

Stenhouse, L. (1975). An introduction to curriculum research and development. London: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Wallace, M. J. (1998). Action research for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]