Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

versión impresa ISSN 1657-0790

profile n.6 Bogotá ene./dic. 2005

M Ashraf Rizvi

Indian School of Mines, Dhanbad, India

ashrafrizvi@yahoo.co.uk

This paper investigates a particular aspect of learner participation – students’ analysis (SA) in an oral communication program of an undergraduate business and commerce curriculum in Sultan Qaboos University, Sultanate of Oman - and examines its role in improving and promoting learning effectiveness in English for Academic Purposes (EAP) classroom discourse. Drawing on the results of a set of surveys into needs analysis, students’ peer response and student feedback, it is suggested that SA can play a significant role by providing wider input into the content, design and implementation of an EAP course by creating opportunities to engage students in interesting and meaningful classroom experiences and providing essential data for reviewing and evaluating the course to improve and promote its effectiveness.

Key words: Students’ analysis, English for Academic Purposes, needs assessment, students’ peer evaluation

Este artículo investiga un aspecto particular de la participación del estudiante – análisis de los estudiantes en un programa de comunicación oral del currículo de un pregrado en negocios y comercio de la Universidad Sultan Qaboos del Sultanato de Oman – y examina su rol en el mejoramiento y promoción de la efectividad del aprendizaje en el discurso del aula de inglés con propósitos académicos. Basado en los resultados de una serie de encuestas sobre análisis de necesidades, respuesta a pares y retroalimentación del estudiante, se puede sugerir que el análisis de los estudiantes (SA) tiene un papel significativo en cuanto proporciona un insumo más amplio en el contenido, diseño e implementación de un curso de inglés con propósitos académicos, ofreciendo así mayores oportunidades para involucrar a los estudiantes en experiencias interesantes y significativas en el aula y brindando información esencial para la revisión y evaluación del curso, para así mejorar y promover su efectividad.

Palabras claves: Análisis de los estudiantes, inglés con propósitos académicos, evaluación de necesidades, evaluación de pares

INTRODUCTION

With the information revolution, globalization and other social and economic changes in the new millennium, the importance of effective oral communication skills has increased. As the professional world becomes more diverse, competitive and result-oriented, success in the highly competitive environment today will depend not just on one’s professional knowledge but on the ability to present that knowledge in an appropriate oral form. Moreover, oral communication skills are cited as the single most important criterion in hiring professionals as most of the professionals are hired through a selection process, which involves oral interaction in the form of a personal interview, group discussion, seminar presentation or some other form of oral communication. Media reports frequently highlight employers’ complaints that graduates’ oral skills leave considerable room for improvement. As Vaughan (2004) rightly argues, “knowledge of highly sophisticated technical or professional skills will be useless if the employee does not know how to communicate with others about the information and insights which result from the use and application of these technical and professional skills”. Students, thus, need specific oral communication skills if they are to be successful in their careers.

Normal teaching constraints as well as the assumption that a traditional teaching framework may not work with a professional oral communication course made us experiment with innovative means to involve students in the teaching process through students’ analysis. It has been largely felt that a very important, rather the most important, element in the process of teaching any language course is the learner and his/her learning needs. The emphasis on needs analysis in EAP course design and program implementation has been rightly justified over the years (Jackson, 2005; Johns & Price-Machado, 2001; Dudley-Evans & St. John, 1998; West, 1997; Jordan, 1997; Ellis & Johnson, 1994). Several new approaches such as target-situation analysis, present-situation analysis, strategy analysis, means analysis, deficiency analysis, genre analysis, and language audits have been advocated by EAP course designers (Dudley-Evans & St. John, 1998; Jordan, 1997; West, 1994, 1997; Bhatia, 1993; Allwright, 1982; Holliday & Cooke, 1982; Richterich & Chancerel, 1980; Munby, 1978).

However, most of the studies that have focused on needs analysis in ESP have largely ignored the possible implications of integrating needs assessment with other aspects of learner participation. The present study is an attempt to explore the integration of needs analysis with other aspects of learner participation in an EAP oral communication program i.e. “Public Speaking for Business”. It is suggested that by integrating needs analysis with peer response and student feedback, teachers can provide wider input into the content, design and implementation of an oral communication EAP course and also create opportunities to engage students in interesting and meaningful classroom experiences. Although the subjects of the present investigation are from a country in the Middle East, the focus and approach have a wider implication for ESP/EAP practitioners in other parts of the world.

STUDENTS’ ANALYSIS (SA)

The term Students’ analysis (SA) is used here to denote a systematic analysis of the target group of students to get relevant information about their perception of their communicative needs and learning-style preferences, peer response and feedback in order to improve the quality of teaching. It is an attempt to explore the implications of using needs analysis in a simple form with other aspects of learner participation. SA, thus, integrates needs analysis, peer response, and student feedback.

Needs Analysis

Needs analysis, as rightly claimed by Jackson (2005), has been ‘the cornerstone of ESP course design, materials development, and program implementation and assessment’. Needs analysis is “the process of determining the needs for which a learner or group of learners requires a language…” (Richards et al., 1992). Theories in adult learning have made it clear that adult students seem to be less interested in learning for learning’s sake than in learning to achieve some immediate life goals. This seems to be more appropriate for business students. Thus, students’ needs analysis is an attempt to make students aware of their learning needs. I am using the term students’ needs to refer to subjective student needs, which are derived from students themselves. I have basically focused on the following three questions:

• Do students need public speaking skills? If yes,

• Why do they need public speaking skills?

• What are their learning-style preferences in a course in public speaking?

Peer Response

Peer response, as defined by Liu & Hansen (2002), is “the use of learners as sources of information, and interactions among each other in such a way that learners assume roles and responsibilities normally taken on by a formally trained teacher, tutor, or editor…” Peer response is increasingly being used by ESL and business communication teachers in writing classes (Rollinson, 2005; Liu and Hansen, 2002, 2005; Bartels, 2003; Braunstein, Meloni and Zolotareva, 2000; Berg, 1999; Hedderich, 1997; Villamil and de Guerrero, 1996; Mendonca and Johnson, 1994; Mittan, 1989), and could be successfully used in oral communication teaching. Using peer response in EAP oral communication classes enables students to understand the purpose of the oral communication process more profoundly than they do with most of their oral assignments. Rizvi (2004: 22) rightly claims that “there are several advantages to having our students give oral feedback to their peers in a group setting”.

Advantages of peer response

• It can be very useful in a variety of oral communication classes.

• It creates opportunities for oral interaction.

• It provides instant feedback on students' oral communication performance.

• Every student gives and receives oral peer response.

• Monitoring peer response is easy with written feedback.

• Assessing students' speaking is easier with quick oral responses.

• It saves time, especially in large classes.

• It provides material for review.

• It is good practice for future teachers.

Student Feedback

We used student feedback primarily as an informal method of collecting students’ feedback on the teaching process. The main purpose of the feedback is to get students’ opinions on the functioning of the course. I used informal discussions and interviews to get students’ feedback. I met students on a regular basis and encouraged them to voice their opinions on the following aspects of the course:

• Teaching method

• Teaching materials

• Classroom activities/tasks

• Course assignments

• Evaluation

There may be different ways of finding information about students. It can be done through various questionnaires, surveys, group discussions, individual talks, interviews, etc. Well, I have used questionnaires, informal discussions and interviews as effective tools in SA.

METHOD

Participants

The participants of the analyses discussed in this paper were 20 Omani students enrolled in an undergraduate commerce program in Sultan Qaboos University, Sultanate of Oman. The English curriculum required teaching intensive language support programs in the first year and three EAP courses, i.e. business communication, public speaking for business and technical writing in the second, third and fourth years, respectively. The participants were in their third year taking the course “Public Speaking for Business”. As calls have been made in recent years for graduates to be proficient in oral communication skills so that they can function effectively in the workplace, “Public Speaking for Business” (PSB) is quite a popular course among the students in the university here. Moreover, the changing nature of business further underscores the importance of oral communication skills. Although EAP courses often target the development of discussion skills for seminar-type classes, Public Speaking for Business involved teaching public speaking skills with an emphasis on developing oral communicative competence in a business setting. Although the four popular published works on academic speaking (James, 1984; Lynch & Anderson, 1992; Madden and Rohlck, 1997; Rignall & Furneaux, 1997) offer guidance to students for structuring and signposting oral presentation and discussion practice tasks, SQU students used a textbook on public speaking for business.

Data Collection

All the data collection of the study was carried out within the framework of the students’ regular classes. First the students were asked to fill in two needs assessment questionnaires. The first (Appendix 1) asked students to provide input on their perceptions of their needs and long-term goals in the area of public speaking while the second questionnaire (Appendix 2) asked the students to comment on their learning style preferences in a course in public speaking. In the middle of the course, students were given Structured Peer Response sheets (Appendix 3) to complete while they listened to the first three oral assignments of their classmates. Next, they were asked to give their comments on the performance of their classmates in the remaining oral assignments as an open evaluation. Finally, through personal interaction and pre-arranged meetings and discussion sessions with the students, the teacher tried to get students’ feedback by encouraging the participating students to comment on the teaching method, teaching materials, classroom activities/tasks, course assignments, use of textbook and evaluation system.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This discussion focuses on students’ responses in three main areas, namely: (1) their learning needs and preferences in public speaking, (2) peer response in public speaking classroom assignments, and (3) their feedback on the teaching process.

Students’ Perceptions of their Learning Needs in Public Speaking

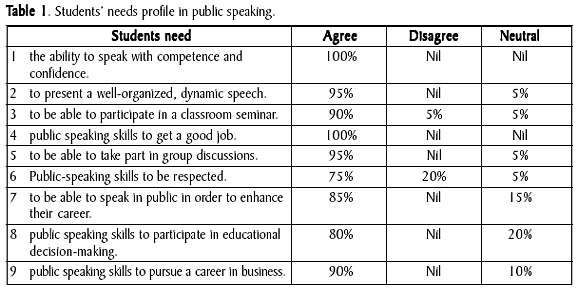

The results of the small-scale needs analysis survey provided some key information about students’ learning perceptions. As you can see (Refer to Table 1 below), the overwhelming consensus from all those responding to the questionnaire reveals a strong awareness of their long-term goals in taking a course in public speaking. One hundred percent of the students agrees that business students need the ability to speak English with confidence and almost ninety-five percent agrees that they need to present a well-organized, dynamic speech. Ninety to ninety-five percent of the students agrees that they need the ability to participate in classroom seminars and group discussions. As to the long-term goals of taking a course in public speaking, one hundred percent of the students agrees that they need public speaking skills to get a good job and ninety percent of them agrees that public speaking skills are needed in order to pursue a career in business. Eighty-five percent of the students agrees that public speaking skills are needed to enhance their career. Eighty-five percent of them thinks they need public speaking skills to participate in educational decision-making while seventy-five percent of the students thinks they need these skills to be respected.

Students’ Perceptions of their Learning

Preferences in Public Speaking

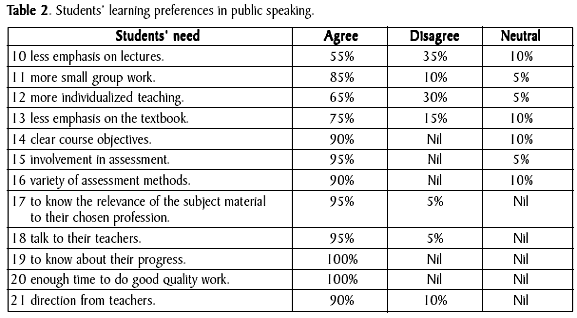

Results of the survey of students’ learning preferences in a course in public speaking (Refer to Table 2) show that students need more small group work and individualized teaching and want to know the relevance of the subject material to their chosen profession with clear course objectives. They want involvement in assessment and demand a variety of assessment methods. They need enough time to do good quality work and need to know about their progress frequently.

Moreover, they need to talk to their teachers as they want direction from them.

Thus, the students’ needs analysis survey does focus on information about learners’ perception of needs and their learning style preferences. From the SNA data, it would seem that

• students are highly motivated and are aware of a need to take a course in public speaking.

• they are aware of their long-term goals for taking a course in public speaking.

• they have strong learning-style preferences.

Peer Response

Through peer response we involved students in the process of student assessment by asking them to assess the performance of fellow students in different students’ presentations and assignments. It included structured peer evaluation, and open evaluation. In structured evaluation, students are provided an evaluation form to complete whereas in open evaluation they are simply asked to grade and write their comments.

A careful analysis of student evaluation sheets of my students provided the following crucial information:

• 80% of the students stated that it created an interested audience for students' public speaking assignments.

• 75% of the students claimed that instant feedback from their classmates helped them to improve their next assignment.

• About 70% could correctly evaluate different aspects of public speaking.

• 70% of the students were able to apply theoretical concepts of public speaking while evaluating the oral performance of their fellow students.

• 45% of the students were able to evaluate delivery techniques in oral presentation assignments.

• 60% of the students did reflect a clear understanding of strategies for creating credible oral presentations and were able to make correct evaluation.

As involving students in meaningful classroom experiences through peer response promotes classroom motivation, we found that our students evaluating the oral performance of their classmates were genuinely interested in communicating their response and comments clearly because they wanted to provide useful feedback. Likewise, the oral presenters eagerly received the peer comments because they wanted to do better on their next assignments and genuinely felt that the comments would highlight their problems and they would be able to improve their performance.

Student Feedback

Student feedback focused on the learners’ perceptions of learning in the course. As the main purpose of this exercise was to get students’ opinions on the functioning of the course, I devised several mechanisms to encourage students to freely comment on the weaknesses and strengths of the course. In particular, they were asked to give their impression about how well the teacher implemented the program as planned. The students were asked if the teaching method used by the teacher was appropriate. I also elicited the learners’ views about the effectiveness of the teaching and course materials to take care of students’ needs and their learning preferences. The students were also asked to pinpoint the positive and negative features of classroom activities, learning tasks, course assignments, use of textbook, and the method of evaluation.

Teaching method

Many of the students revealed that the method of teaching was simple and they were able to follow the lectures easily but they demanded more involvement of the students in the classroom. They felt that the teacher ought to provide students opportunities to speak on general topics in the classroom on a regular basis. They also wanted a reduction in the discussion on the theoretical concepts of public speaking and felt that they needed more practice in public speaking. Some of them indicated that they had inadequate communication skills and were reticent in classroom discussions because they had little or no opportunity to speak English in public. Some students wanted more emphasis on individualized teaching because they felt that the students in the classroom had different proficiency levels in English speaking due to their differing social and educational backgrounds.

Teaching materials

Many students felt that the textbook used in the classroom was very difficult. Most expressed the view that they needed simplified course materials and teaching notes to understand the basic concepts discussed in the course. Although many students suggested that the textbook could be supplemented by appropriate remedial study materials, some students felt that the textbook could be replaced by simple course materials to be developed by the teacher. However, the provision of simplified course materials and teaching notes seemed to be a major concern of all students.

Classroom activities/tasks

Students held differing views about classroom activities. Some students acknowledged that the classroom activities were useful and the teacher did everything possible to make these activities meaningful as well as useful to students. However, some students did not believe this and felt that smaller group activities were needed. Some of them suggested that the activities needed to be more interactive and student-centred. Many students felt that they needed more classroom discussions and oral exercises. A few students expressed the view that the number of non-credit classroom presentations should be increased.

Course assignments

Many students noted that the course assignments were well organized and their implementation was effective. However, they needed more time before each presentation. Some students felt that the gap between two presentations should be longer. Many students suggested that the number of assignments should be reduced to give students more time to prepare for a presentation. Some students wanted flexibility in the time-frame chosen by the teacher and opposed the idea of penalizing students who submitted the assignment late.

Evaluation and grading

Students held differing views about evaluation and grading. Some students acknowledged that the teacher was very impartial in evaluating the assignments and presentations but a few students did not agree. They felt that the teacher was slightly biased towards good and regular students. Some students believed that they deserved better grades than those they were awarded by the teacher. Many students suggested that peer evaluation should also be considered while evaluating the individual performances of students. A few students commented that the marking was too rigid. Better grading seemed to be a major demand of all students and they made several suggestions to liberalise marking and the grading system.

All the comments of students were noted. A systematic analysis of these comments gave me enough ideas to make changes within the framework. I could implement some of the suggestions given by the students.

CONCLUSION

We believe that by the use of a framework of students’ analyses as described here, teachers can involve the students in the learning process and provide essential data for reviewing and evaluating the course to improve and promote its effectiveness. As any EAP oral communication course should be not only need-based, but also learner-centered, students’ analysis can play a very significant role by providing wider input into the content, design and implementation of the course. Moreover, it can provide opportunities to engage students in interesting and meaningful classroom experiences.

Teachers can effectively use students’ analyses as a tool to improve learning effectiveness in their classes. Firstly, an integration of needs analysis, peer response and students’ feedback can prove to be an effective means of obtaining wider input into the content, design and implementation of an EAP program as it provides essential data for reviewing and evaluating an existing EAP program to improve and promote its effectiveness. Secondly, by getting learners involved in the learning process through peer response and student feedback, it can promote reflective learning. Reflective learning encourages, as argued by Mezirow (1990: 366), ‘critical reflection in order to precipitate or facilitate transformative learning in adults’. Similarly, Schon (1991) claims that reflection can change traditional learning into a transformative and emancipatory experience. By analyzing their communicative needs, expressing their learning preferences, and by giving peer feedback, students become more aware of what they need as course participants and develop skills to reflect on their learning process. Finally, students’ analyses can motivate students by engaging them in interesting and meaningful classroom experiences.

Although the study presented here is limited to a particular context as the subjects of the present investigation are from a country in the Middle East, the focus and approach have a wider implication for ESP/EAP practitioners in other parts of the world. In fact, the results would seem to be compatible with second language acquisition studies concerning the creation of learning experiences and opportunities. On the basis of this, the conclusion is that encouraging learner participation through SA may have positive outcomes on successful language learning, and EAP teachers, particularly those teaching oral communication courses, should therefore seek practical ways of introducing this into the EAP classroom.

THE AUTHOR

M Ashraf Rizvi is an Assistant Professor of English at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian School of Mines, Dhanbad. His previous assignment was with Sultan Qaboos University, the National University of the Sultanate of Oman, where he taught business communication courses as Assistant Professor and program Co-ordinator. He has been an External at Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages, Hyderabad and a Course Writer of Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi. He has authored a series of textbooks for business and technical communication. He has also written articles in the area of oral language development and ELT. His special interests include students’ analysis, learner autonomy, material production, and error analysis.

REFERENCES

Allwright, R. (1982). Perceiving and pursuing learners’ needs. In M. Geddes and G. Sturtridge (Eds.), Individualisation (pp.24-31). Oxford: Modern English Publications. [ Links ]

Bartels, N. (2003). Written peer response in L2 writing. English Teaching Forum, 41 (1), 34-37. [ Links ]

Berg, E.C. (1999). The effects of trained peer response on ESL students’ revision types and writing quality. Journal of Second Language Writing 8 (3), 215-241. [ Links ]

Bhatia, V. (1993). Analysing genre: Language use in professional settings. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Braunstein, B., C. et al. (2000). The U.S.-SiberLink Internet project. TESL-EJ, 4 (3), 1-23. [ Links ]

Dudley-Evans, T. & St. John, M. (1998). Development in English for specific purposes: A multi-disciplinary approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ellis, M. & Johnson, C. (1994). Teaching business English. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Hedderich, N., (1997). Peer tutoring via electronic mail. Unterrichtspraxis, 30 (2), 141-147. [ Links ]

Holliday, A. & T.Cooke. (1982). An ecological approach to ESP. Lancaster Practical Papers in English Language Education, 5 (Issues in ESP). University of Lancaster. [ Links ]

Jackson, J., (2005). An inter-university, cross-disciplinary analysis of business education: Perceptions of business faculty in Hong Kong. English for Specific Purposes, 24 (3), 293-306. [ Links ]

James, K., (1984). Speak to learn: Oral English for academic purposes. London: Collins. [ Links ]

Johns, A. & Price-Machado, D. (2001). English for specific purposes: Tailoring courses to students needs- and to the outside world. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (pp.43- 54). Boston: Heinle and Heinle. [ Links ]

Jordan, R.R., (1997). English for academic purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Liu, J. & Hansen, J.G. (2005). Guiding principles for effective peer response, ELT Journal 59 (1), 31-38. [ Links ]

Liu, J. & Hansen, J.G. (2002). Peer response in second language writing classroom. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

Lynch, T. & Anderson, K. (1992). Study speaking: A course in spoken English for academic purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Madden, C.G. & Rohlck, T.N., (1997). Discussion and interaction in the academic community. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

Mendonca, C.O. & Johnson, K.E. (1994). Peer review negotiations: Revision activities in ESL writing instruction. TESOL Quarterly 28 (4), 74-769. [ Links ]

Mezirow, J. (Ed.). (1990). Fostering critical reflection in adulthood. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Mittan, R., (1989). The peer response process: Harnessing students’ communicative power. In D. Johnson and D.Roen. (Eds.), Richness in eriting: Empowering ESL students (pp. 207-219). New York: Longman. [ Links ]

Munby, J., (1978). Communicative syllabus design. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Richards, J.C., et al. (1992). Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Richterich, R. & J.L. Chancerel. (1980). Identifying the needs of adults learning a foreign language. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [ Links ]

Rignall, R. & Furneaux, C. (1997). Speaking. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Rollinson, Paul. (2005). Using peer feedback in the ESL writing class. ELT Journal, 59 (1), 23-30. [ Links ]

Rizvi, M.A., (2004). Teaching oral communication skills to business English learners. Journal of Communication Practices, 1 (1), 13-24. [ Links ]

Schon, D.A., (1991). The reflexive turn: Case studies in and on educational practice. New York: Teachers’ College. [ Links ]

Vaughan, D.K. (2004). The impact of the new global economy on business communication skills. Journal of Communication Practices, 1 (1), 3-11. [ Links ]

Villamil, O.S. & De Guerrero, M.C. (1996). Peer revision in the L2 classroom: Social, cognitive activities, mediating strategies, and aspects of social behaviour. Journal of Second Language Writing 5 (1), 51-75. [ Links ]

West, R. (1994). Needs analysis in teaching: State of the art. Language Teaching, 27, 1-19. [ Links ]

West, R. (1997). Needs analysis: State of the art. In Howard, R., & Brown, G. (Eds.), Teacher education for LSP (pp. 68-79). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual matters. [ Links ]