Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile no.7 Bogotá Jan./dec. 2006

Enrique Alejandro Basabe1

1M. A. in English Language Teaching and British Cultural Studies, The University of Warwick, Coventry, UK. Currently a student in the Maestría en inglés, UNRC, Córdoba, Argentina. Teacher of English Literature of the 20th Century at Universidad Nacional de La Pampa, Santa Rosa, La Pampa, Argentina. Hornby Alumnus.

quiquebasabe@yahoo.com.ar

It is generally acknowledged that the culture of English-speaking countries has abandoned its central role in recent ELT materials. However, this study suggests that representations of the Anglo-American culture are still favoured in ELT textbooks but that, in most cases, they have been transformed into “international” attitudes. This idea is tested by the compilation of lists of cultural references for four series of textbooks in use in Argentina, and by the application of the procedures of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to a selection of reading passages from them. The findings provide an answer as to what representations of English-speaking cultures are in current textbooks and open to debate the apparent fairness of English as an International Language (EIL).

Key words: Cultural representations, culture of English-speaking countries, materials design, English as an international language, critical discourse analysis

Existe un consenso casi generalizado en que la cultura de los países de habla inglesa ha abandonado su papel central en los textos de inglés como lengua extranjera. Sin embargo, se sugiere que las representaciones de la cultura Anglo-americana aun persisten sólo que transformadas en actitudes “internacionales”. Esta idea se pone a prueba mediante la compilación de listas de referencias culturales en cuatros series de libros en uso en Argentina y en el Análisis Crítico del Discurso (ACD) de una serie de textos destinados a la lectura en dichos volúmenes. Los resultados determinan qué representaciones culturales subsisten en los textos y abren al debate la aparente neutralidad del inglés como lengua internacional (EIL, por sus siglas en inglés).

Palabras claves: Representaciones culturales, cultura de los países de habla inglesa, diseño de materiales, inglés como lengua internacional, análisis crítico del discurso

ELT TEXTBOOKS AND THE REPRESENTATIONS OF CULTURES

Textbooks belong in our cultural universe and are powerfully inscribed in our social knowledge. They are informed by systems of representations, or “different ways of organizing, clustering, arranging and classifying concepts, and of establishing complex relationships between them” (Hall, 1997, p.17). These systems, in turn, reach moments of arbitrary closure in which the linkages established among them become powerfully tied into articulated discourses. Through the textbooks we use, our learners are constantly exposed to these systems, so it is almost mandatory to examine them closely since there may be “a direct relationship between the values and attitudes learners express and those found in the texts with which they work” (Littlejohn & Windeatt, 1989, pp.171-172).

Traditionally, the cultural systems represented in ELT textbooks were those of the countries where English is spoken as a first language, mainly the United Kingdom and the United States of America. From the 1990s onwards, however, the demand of consumers for a better fit to local contexts in the highly competitive publishing industry has generated a rising awareness of the cultural contents already present and of the ones which should be promoted in ELT materials. This, together with the advent of the integrative theoretical discourse of English as an International Language (EIL), have led scholars to suggest

• “that learners do not need to internalise the cultural norms of native speakers;

• that ownership becomes de-nationalised; and

• that the educational goal is to enable learners to communicate their ideas and culture to each other” (McKay, 2002, p.12).

Some have gone even further and called for the “deanglicization” of English “both in linguistic and cultural respects” (Alptekin, 1990, p.23). This process has led to an apparent displacement of the “target culture” from its central position, a shift which has paved the way for the consideration of the “source culture”, or the learner’s own background, and of an emerging “international culture” inclusive of non-English-speaking countries2 . It is now generally acknowledged that the culture of English-speaking countries has abandoned its central role and given way to a fairer inclusion of local and international cultures in recent ELT materials. This study questions whether or not such has been the case and it suggests that representations of the Anglo-American culture seem to be still quantitatively and qualitatively favoured in ELT textbooks. If this is so, then the apparent neutrality and fairness of EIL may be questioned or, at least, open to debate.

CORPUS, RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND METHODS

Four series of textbooks in use at the Third Level of the General Basic Education or with adolescents in private institutes in 2003 in Argentina were chosen for the sake of testing the hypothesis suggested above. They are the following:

• New Headway. Pre-Intermediate and Intermediate. A global coursebook published in the UK between 1996 and 2000 used in private institutions;

• New Let’s Go for EGB 1 and 2. (from now on NLGforEGB) A global course book produced in the UK under the name of Go! (1996) adapted to the local market from 1999 to 2000 and used widely in the Third Level of the General Basic Education,

• English Direct 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, 3A and 3B. A course book produced in Mexico to teach American English adapted to teach British English in Argentina in 2001 and specially offered by the publishers to disadvantaged schools, and

• Explorer 1, 2 and 3. A local course book written in Argentina for the local market from 1999 to 2001.

The first question that guided this investigation was

• How the repertoires of representation of the target culture, i.e. the UK and the USA, are put into discourse.

The findings suggest tentative responses to a second query,

• Whether and how these systems of representation differ or not on the basis of the context of production of the textbooks and their discourse.

The research process entails a study of the representations of the target culture in view of the ways in which it appears in global, adapted or locally -produced teaching materials. It was carried out using two different methodological tools, one to gather quantitative data and the other one to qualitatively validate the findings of the former.

Firstly, a decision had to be taken as to what was going to be considered “cultural”, which was solved by the application of the analytical categories suggested by Risager (1990) and which encompass a consideration of phenomena of social and cultural anthropology as well as international and intercultural topics. See Appendix 1 for further reference. Using these categories, lists of cultural references were compiled. Their concoction followed the model Byram used to assess representations of Germany in textbooks used to teach German to speakers of English in 1993. This model consists of succinct preliminary comments on the cultural contents of the reading passages of the series of textbooks under analysis. For further reference, see Appendix 2. It shows the list of cultural references regarding the target culture in New Headway Pre-Intermediate.

Once listed, the references were classified into “topics”, as shown in the Findings. The notion of “topics”, even though at first considered pre-theoretical, was preferred as it is widely used in the context of ELT. This process was thought of as a preliminary instance of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), in the sense that articulations into systems of representations were suggested and interpretative hypotheses were developed while the reading and ensuing listing were going on.

Secondly, the basic procedure for Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) proposed by Fairclough (1989, pp. 110-111) was applied to a selection of reading passages of approximately 400 (four-hundred) words chosen at random from each of the series. This instance entails an examination of the uses of vocabulary, grammar and textual strategies as well as a consideration of the different realisations of narrative and conceptual representational structures in photographs and pictures accompanying reading passages following Kress and van Leeuwen’s proposal for a semiotic analysis of images (1996). For a summarised version of Fairclough’s model, refer to Appendix 3. For an application of it to a particular text, see Appendix 4. Last but not least, the findings resulting from the previous two steps were compared and contrasted on the basis of their belonging to global, adapted or local materials.

FINDINGS

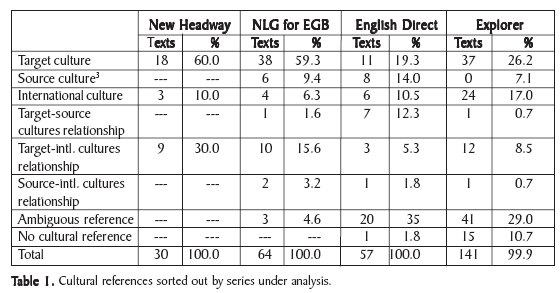

Table 1 shows the results of the quantitative data produced by the lists of cultural references for each book. In all cases the references to the target culture are more frequent than those to the source or the international cultures, in New Headway and NLGforEGB (approximately 60 %). Moreover, there are only two cases in which another type of reference overcomes those to the target culture and these are ambiguous references in the series English Direct and Explorer. In these series, however, the target culture still keeps 19.3 % and 26.2 % of the cultural references, respectively, occupying the second place after the cases of unclear references. Texts containing cases in which there exists a relationship between the target and the international cultures are also the commonest among these containing cultures establishing some kind of contact. These cases represent 30 % in New Headway, 15.6 % in NLTG for EGB! and 8.5 % in Explorer.

Representations of the Target Culture

The cultures of the UK and the USA have prevailed as the ones chosen to be represented in the textbooks under analysis. In the reading texts in the coursebooks constituting the corpus of this work, the target culture is represented through the topics and in the percentages displayed below.

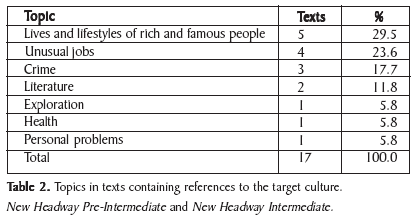

Of the 30 texts included in the list of cultural references for New Headway Intermediate and New Headway Pre-Intermediate, 18 contain cultural references pointing at the target culture, which accounts for 60 % of the total of the passages destined for reading comprehension. The commonest topics dealt with by these texts are he lives and lifestyles of rich and famous people (29.5 %) and unusual jobs (23.6 %). US millionaires constitute the vast majority of the ones under the former label and British subjects who choose to change their lifestyles –a nun who becomes a TV star, a vicar who works as a ghost buster and a retired plumber who skates for Tesco, for example– comprise most of the cases in the latter label. Other texts include references to crime (17.7 %) and literature (11.8 %), as shown in the following table:

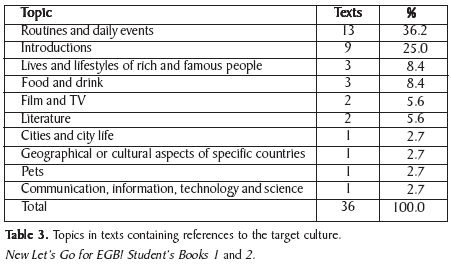

Fifty-nine percent of the reading texts in NLGforEGB Student’s Books 1 and 2 refer to the target culture. In most of the 38 texts that make up this percentage this reference encompasses the social and geographical definition of characters and the material environment surrounding them as the story in the textbooks features a group of students on board a ship sailing along the coast of the UK. Thus, routines and daily events (36.2 %) and introductions (25.0 %) are necessarily situated in a British context.

As it can be seen in the table below, the lives and lifestyles of rich and famous people represent 7.9 % of the texts pointing at the Anglo-American culture. The text “Billie” (Elsworth, Rose & Date, 1999, pp. 44-45), studied using the tools provided by CDA, belongs in this category. It constructs a world in which adolescents can be rich and famous from a very early age and still live a “normal” life, respectful of family and national values since sudden popularity seems not to cause any problem for teenagers raised in traditional family and school settings.

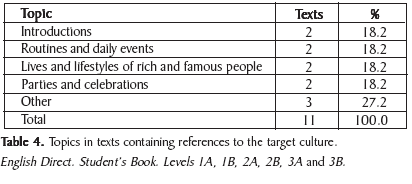

As can be appreciated below, in English Direct, the amount of texts referring to the target culture does not reach a percentage as high as the ones in New Headway and in NLGforEGB! Only 11 passages out of the 56 reading texts the series contains allude to the target culture, which accounts for 19.3 % of the total. Neither do any of these exts refer to British culture, but to introductions, daily routines, the lives and lifestyles of rich and famous people and parties and celebrations set in the USA or in Australia. Each of these topics constitutes 18.2 % of the overall quantity of references to the target culture in the textbooks.

One of the texts on which CDA was applied falls into this category as it describes the world premiere in New York of a film by an Australian cartoonist. Its analysis reveals a world in which the accumulation of “objects” (Llamas & Williams, 2001d, p. 14), for example, becomes the evidence of fame and wealth. These also appear to be part of the everyday life of people belonging to the target culture.

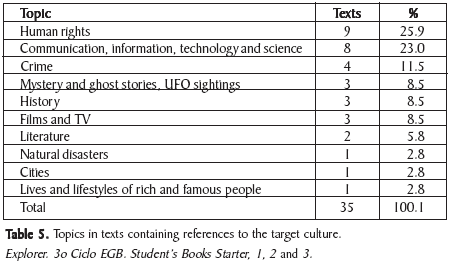

As can be seen in the table above, the series Explorer contains 35 texts with references to the target culture, which stands for 26.2 % of the total amount of its reading texts. Here, topics show a wider variety than in the previous textbooks since, in most cases, texts are introduced as encyclopaedic entries of a purely informative nature. Twenty-five point nine percent of them, however, are concerned with narratives in which members of the target culture fight for their human rights and achieve their aims. The cases of Nelson Mandela, Emmeline Pankhurst, Francis Robinson and Martin Luther King can be counted among them. The manipulation of communication and information mainly through the Internet and the advances of technology and science are also recurrent topics in the reading passages. They constitute 23.0 % of the texts related to the UK and the USA. Four texts (11.5 %) portray a society fighting against crime. There are also references to English history and literature, films and TV, natural disasters, cities and the lives of rich and famous people. The text, “A macabre job” (García Cahuzac & Tiberio, 1999, p. 49), included in Appendix 4, is remarkable as its critical analysis shows an evident rewording of the “crime” of robbing newly buried bodies from cemeteries in the England of the 18th century into a “job” carried out in the name of the progress of medical science and out of the needs of poor people. Thus, the target culture, its academic institutions and its higher classes are discursively freed from the stigma of illegality.

Representations of the Target Culture in Relationship to Others

Not always are the cultural references in textbooks so clear and distinct that they allow classifying reading passages with utmost accuracy. Sometimes cultures experience contact with one another, they are compared or contrasted, or, simply, information about more than one culture is contained within the limits of only one text. Tables are not included in order to keep the article at an appropriate length and not to pack it with quantitative data. For figures and percentages, please refer to Table 1.

Thirty percent of all the texts destined to be used for reading comprehension in New Headway comprises instances of the target and the international cultures in contact. Most of them are about the lives and habits of people from international cultures. Others, for example, evaluate negatively the economic evolution of Warsaw, Poland, and Shenzhen, China, both cities that used to live under communist governments, after having gained access to the capitalist world. The majority of texts, though, retell stories of either Europeans or Americans exploring, touring or consuming resources from places set in international cultures or of people from such cultures migrating to the USA. The article from New Headway upon which CDA has been applied, “Three plants that changed the world” (Soars & Soars, 2000, p. 91), belongs to this group of texts and reinforces the view of an active European citizen “conquering” the world for his own profit and well-being. In it, crops like tobacco, sugar and cotton are rendered natural resources to be consumed by Europe, the “world” these plants “changed”. Moreover, the world and lives of other people that were also changed by these crops becoming lucrative is barely described or deemed to be forgotten if ever hinted at. Last but not least, this worldview runs the risk of appearing naturalised through the inclusion of photographs accompanying the text that reproduce the working context of the past in distinctly non-temporal situations thus helping construct the idea that these circumstances are still standard and fair.

Only 13 texts in NLGforEGB Student’s Books 1 and 2 contain references to more than one culture, of which only 3 can be said to constitute instances of intercultural personal communication. These are letters from a member of the target culture and the corresponding answer from a Brazilian boy (Elsworth et al., 1999, pp. 36-37), which in fact and within the confines of the texts themselves, still remain cases of monologue. Most of the rest of the reading passages only display facts and figures, stamps, animals and celebrations belonging to different countries, all of them elements that are never shared by more than one culture and are always presented as exclusive of one particular cultural group. The reading text, “What is Sea Watch? Who are the Sea Watchers?” (Elsworth et al., 1999, p. 22), discloses a world in which students from the target, the source and the international cultures can share educational programmes in view of their common global interests, institutions, attitudes and codes of conduct that unite them under an aura of mutual understanding. The disposition of the texts and the corresponding illustrations in the brochure, however, reveal by implication a totally opposite worldview. The participants are introduced in an overtly classificatory representational manner by which the South American teenagers occupy the top half of the structure and the British and American adolescents the bottom half, thus reinforcing the idea that target and source cultures never mix. Nor do target and South American cultures, either.

By contrast, English Direct shows instances of the target, the source and the international cultures in contact. Nevertheless, as in New Headway, it stereotypically represents the members of the target culture as active explorers and adventurous tourists and those of the source culture as passive workers related to the tourist industry or humble immigrants arriving in the USA. Two texts from this series were critically analysed. One retells Ernest Hemingway’s catch of a big marlin on the coast of Peru when his novel The Old Man and the Sea was being made into a film (Llamas & Williams, 2001d, pp. 8-9). It transpires that the passage embodies the theme of the man of letters who dares plunge into exploring adventurous activities different from his usual activities –in this case, fishing–and, consequently, creating an impressive effect on ordinary people –here, the Cabo Blanco fishermen. The other text under analysis is a conversation in which an Argentine man arriving at an American airport is asked to show his passport to an officer at a check-in desk (Llamas & Williams, 2001a, pp. 12-13). The illustration that accompanies it is indicative of the authoritative view of the target culture. Firstly, it strikingly antagonises he arrival of the Argentine, dressed in simple clothes and placed in a bottom-left position in the drawing, with that of an Italian actress clad in jewels and a fur coat, visually-centred and surrounded by photographers. This obviously marks the social, economic and even political position not only of the particular people involved in the narrative action but also of the countries and the cultures they represent. Secondly, the skin colour of the Argentine in the illustration is revealing of the racial dichotomy English Direct creates. As in all other illustrations in the series, Argentine people are always dark-skinned, which makes them distinctive when compared with the pale pink complexions of the American and European subjects4. This implicit hint of racism, however, seems not to produce any particular problem for the world created by English Direct and this is visually emphasised through its illustrations. See Appendix 5 for further references. In Explorer, there are 14 texts that refer to more than one culture. Twelve texts are concerned with the relationship between the target and the international cultures. Among them are those in which British expeditions to places faraway from the UK are narrated.

DISCUSSION

The choice of which culture is representative of the target culture as a whole has got its variations in the different types of textbooks being analyzed.

In New Headway and NLGforEGB, elements of the culture of the UK are the ones that cover longer stretches of text. In the former, this is mainly due to the texts being mostly from British newspapers such as The Daily Mail, The Observer, The Telegraph and The Guardian, the target culture thus retaining for itself the power of surveillance over the world, even over such culturally remote places as the cases of Poland and China already mentioned. In the latter, the British material environment of its narrative structure causes the geographical and social landscape of England to flood the text, as the teenagers on board the ship live their unproblematic lives. In Explorer, the approach can be said to be somewhat more balanced since, if “things British” pervade the texts through references to the history and literature of the UK, Americana flows in them through the scientific and technological advances of the USA.

In these matters, English Direct becomes contradictory since it linguistically prefers British English, in accordance with the long-standing Argentine tradition that follows this variety, but culturally favours American people and places and contains almost no hint of the British culture. Other English-speaking countries such as Canada and Australia sporadically appear in the textbooks.

However, the representation of the target culture in view of the topics related to it is highly homogenous in all the coursebooks no matter whether they are global, adapted or local products. The lives and lifestyles of rich and famous people, such as those of Michael Owen, Bill Gates or Milton Petrie and Hetty Green, construct the world of the target culture as one in which fortune and success are within one’s reach and accessible even to people with working class origins like the British footballer here cited. If this is not the case, the society of the target culture lets its subjects fight for a better world, therefore achieving some kind of success. This is shown mainly in Explorer through the cases already mentioned.

In the textbooks, the people from the target culture are characterized by at least three traits that make them distinct from that of the source and international cultures. They are technologically advanced, culturally rich and geographically expansionistic.

Technology is usually in the hands of the target culture. It may be accessible to more “ordinary” people but only in instances of personal communication or schooling. Otherwise, it is controlled by the USA, as in the case of the Internet or it has provided the Americans with the tools to simply defeat the Russians in the race for space exploration without any further contextual explanation.

The culture of the English-speaking countries is judged to be “rich” in view of the references to English literature and American cinema present in the texts. Dickens, Wilde and Stevenson are included in the textbooks as if it were “natural” for teenagers all over the world and, in this case, in Argentina, to be instructed in the literature written in England in the 19th century. If something “helps” bridge this spatial and temporal gap, this is American cinema and television, overwhelmingly present in almost any contemporary society and whose popular films and series similarly cover long stretches of current ELT textbooks. In Explorer, The X Files and Die Hard are instances of this as are most of the fictional reading texts whose narrative elements evidently resemble those of American thrillers. It should be noticed here that the rest of the fictional texts in this series seem to have been written after 19th century English mystery stories as well. This shows a particular emphasis on the cultural symbiosis current textbooks seem to create between the English literature of the 19th century and the American cinema of the 20th century. Thus the dissemination of Anglo-American values carried out by the latter appears to be more than an extension of the enterprise started by the former.

Similarly, current American tourism seems to embody the geographically expansionistic spirit of British exploration of the 19th century. This is shown by the American couple touring Europe in New Headway e.g. Paul Howard looking for “adventure”, bungee jumping in Mexico in Explorer, the Waltons’ trip to Machu Picchu in English Direct, or the presentation of Argentine cities as sites receiving only international tourism in NLGforEGB. This is also true of the references to explorations to Spain, Switzerland, the Andes and the Poles. The settings where these actions occur, mostly places other than Europe, seem to have suffered the authorial process of “insubstantiation” by which landscapes are described only as backdrops for European voyages. On the contrary, NLGforEGB is set in the UK. Here, tourism emerges as a culturally “safe” topic experienced by fictitious students whose activities are mostly trivial involving situations of spare time clearly marginalized from ordinary life (Risager, 1990, pp. 185-186).

In all other instances, however, members of the target culture live in cities that are “modern” and “reflect their people” (García Cahuzac & Tiberio, 1999, pp. 14-15) and usually suffer the threat of crime as shown in New Headway and Explorer. The “problem” is constructed as one that is endured by society as a whole. Therefore, the absence of other problems, such as those which may be effectively suffered by teenagers, implicitly signifies that they remain “marginal” expressions undermining society per se.

Moreover, problems, as well as voyages, literary and filmic achievements and technological advances, are not really aspects of social binding and solidarity but the results of a society which emphasises “individual development and personal experience” (Cortazzi, 1999, p. 57). This society, which much resembles the one envisioned by the Thatcherism and Reaganism of the 1980s, have been effective in expanding its hegemonic views not only of itself but also of the world to the globe through its “self-presentation as universal, one that does not acknowledge its own particularity” (Stratton & Ang, 1996, p. 364), as is also shown through its representations of the source and international cultures.

The authors of the textbooks agree on their highlighting the “international” character of the topics they discuss. Headway declares on its cover that it contains “new universal topics”. The authors of NLGforEGB, in turn, claim that their production “has a truly international feel” (Mugglestone, Elsworth & Rose, 2000, p. iii). Llamas and Williams (2001g, p. 2) declare in English Direct, “topics such as environmental protection, respecting others and cultural differences are carefully incorporated into the lessons”. Cresta, García Cahuzac, and Tiberio suggest that teachers use Explorer to make students discuss “why English should be learnt, mainly English for International Communication” (1999, p. 24). Last but not least, reference should be made again to the teacher’s book by Mugglestone et al. They summarise a common stance on the issue when they posit that “learning a foreign language is seen […] as part of the broader educational goal of learning: to live in the modern world in the global sense” (2000, p. xiii). These assertions, however, should be tackled cautiously and critically.

On the one hand, the risks of an internationalisation or universalisation of interests in view of the attention they get from a dominant minority, i.e. mainly Europe and the USA, become actually evident. The case of environmental protection is a paradigmatic one that deserves further discussion. In recent years, it has become a fashionable issue to be included in ELT textbooks as “it reflects a growing interest in nature conservation” (Mugglestone et al., 2000, p. 1T22). Certain issues are not considered, though, such as where and why the interest grows and whether it actually constitutes a genuine concern. The burning of oil wells as a result of their bombing by the military forces of countries in which the environmental question creates popular anxieties, or the destruction of the rainforests to raise cattle in their places to provide American restaurants with meat (García Cahuzac & Tiberio, 2001, p. 57) may hint at probable answers to these queries.

On the other hand, the ultimate claim that learning a foreign language in order to gain access to the modern world is part of the broader educational aim of learning may be equally arguable. First, the generalisation itself may not be valid in each and every educational context, since not every human being on earth might agree with such a “global” goal. In fact, there exist anti-globalisation movements, not to mention real people all over the world who, even though they strive to learn at least the basic English required to manage modern information technologies, will never share the “advantages” of modern life. For these people, learning English may be perceived as a must, but not necessarily enjoyed. As Pagliarini Cox and de Assis-Peterson (1999, p. 438) posit, the discourse in favour of the instrumental orientation provides a release from subjugation by a located and tangible culture and leads to another subjugation by an intangible and scattered plot of discourses that have promoted the Westernization of the world for more than two millennia.

CONCLUSION

The promotion of ELT textbooks produced by increasingly global commercial enterprises may be “aimed ultimately at boosting commerce and the dissemination of ideas and language” (Gray, 2002, p. 156). Global economic processes, hand in hand with “the view of English as an international and therefore neutral language, a view central to the discourse of EIL [may] resurface[s] in the form of a new ‘international content’ for ESL textbooks” (Pennycook, 1994, p. 45), which may mean an actual change in the repertoires of representation around “difference” and “otherness”. The production of textbooks can also be posited to be an ideological enterprise. As cultural artifacts, they may be said to have remained as “stubbornly Anglo-centric” (Prodromou, 1988, p. 74) as they were during the Cold War era, for instance, in which case earlier representational traces may have remained intact in contemporary society.

Despite claims of a progressive de-Anglo-Americanization of the cultural aspects of ELT materials since the 1990s, a critical discursive view of them in the textbooks analysed proves that the process has fallen short of actually representing cultures in a fair way both quantitatively and qualitatively. The world constructed by these coursebooks still remains one in which the English-speaking countries are not only linguistic but also cultural “targets” the globe has to aspire to, imitate and follow. These aims, however, have been, in most cases, transformed into “universal” or “international” attitudes we all seek to share and identify with. Alptekin, for instance, explains the satisfactory acquisition of English in the Greek context by saying it is due to the students’ “wish to identify with international attitudes which have developed in such fields as pop culture, travel culture, and scientific culture where English happens to be the principal medium of communication” (1993, p. 23). It is arguable whether pop culture, travel culture, and scientific culture actually are “international” or whether they may be said to have been “internationalised”. Moreover, it is also disputable whether English just “happens to be” the global language that carries these cultural messages.

Furthermore, this way of representing cultures seems not to show any substantial differences in view of the materials considered being global, adapted or local. Such a situation may be said to be duplicitous in view of most of the theoretical discourse of EIL. If learners do not need to internalise the cultural norms of native speakers of English, then it is contradictory to propose the acquisition of knowledge about the target culture and to reflect on how their own culture contrasts with it. This assumption points to a naturalisation of this “contrast”. It does not acknowledge the fact that, as cultural artifacts, textbooks embody the belief systems of the societies from which they originate (Wallace, 2002, p. 113) and that, therefore, they are instrumental to this process. As it has already been proved, even though trying to come to terms with cultural diversity, the course books analysed still seem to project “an Anglo-American utopia” (Prodromou, 1988, p. 79) which, instead of fostering a reflective judgement and a critical evaluation of the products of the target culture (Corbett, 2003, p. 13), seems to be promoting an acquiescent and uncritical reception of them and of the patterns of behaviour fostered by them. Moreover, if the ownership of the English language becomes de-nationalised, then the textbooks analysed have a tendency to be incompatible with this assumption as they try to strengthen the representation of the UK as an ideal modern European nation and they covertly nurture a growing internationalisation or Westernization of trends and attitudes.

Not less important than providing explanations that account for the cultural representations textbooks convey is the consideration of the context of reception in which these configurations have an impact. There may be a direct relationship between the values and attitudes learners express and those found in the texts with which they work. Therefore, students may tend to concur with the ideas of an Anglo-American superiority and of an Argentine fate to be part of a stagnated working class. Or they may also follow the pattern of excessive imitation. Or they may even resist not only the cultural but also the linguistic content of ELT textbooks as they consider both to be almost an “absurd” imposition of foreign powers. This is generally true in less favoured social contexts in which students tend to have higher degrees of underachievement, and question the usefulness of learning a foreign language. Solutions to this issue appear to be also difficult to find, as an excessive emphasis on critical reading could end up in developing further and stronger resistance to English. But an uncritical and compulsory acceptance of the views thrust upon students by teachers and textbooks alike may lead to servile submission and to the actual death of any hope of social change.

1. This work is partially based on the unpublished M. A. Dissertation The representation of cultures in ELT materials: A comparative analysis of global, adapted and local courses written at the Centre for English Language Teaching at The University of Warwick in Coventry, UK, in 2004, studies completed with the help of a scholarship from the Hornby Trust administered by The British Council.

2. Even though useful as a classificatory tool, the distinction of these three types of cultural information proposed by Cortazzi and Jin (1999) already maintains the culture of the English-speaking countries in its central or “target” position, which is debatable in view of the de-nationalisation EIL promotes.

3. More information on the representation of the source culture in the textbooks under analysis can be found in Argentina. Its Representations in Local and Adapted ELT Textbooks. 30th FAAPI Conference Proceedings. Towards the Knowledge Society. Making EFL Education Relevant. (2005): 380-391.

4. This is also true of the Argentine and Brazilian teenagers in the photographs in the text on nationalities from NLGforEGB, already discussed, and of the workers in tobacco, sugar and cotton plantations in the photographs accompanying the text from New Headway, already introduced.

REFERENCES

Alptekin, C. (1990). Target-language culture in EFL materials. ELT Journal, 47(2), 136-143. [ Links ]

Byram, M. (Ed.). (1993). Germany. Its representation in textbooks for teaching German in Great Britain. Frankfurt/Main: Verlag Moritz Diesterweg. [ Links ]

Corbett, J. (2003). An intercultural approach to English language teaching. Clevendon and Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters Ltd. [ Links ]

Cortazzi, M., & Lin, J. (1999). Materials and methods in the EFL classroom. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Culture in second language teaching and learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Cresta, E., García, S., & Tiberio, S. (1999). Explorer one. 3o ciclo EGB. Teacher´s book + Guía didáctica. Buenos Aires: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

Elsworth, S., Rose, J., & Date, O. (1999). New let´s go for EGB! Student´s book 1 with activity book. Harlow, England: Addison Wesley Longman Ltd. [ Links ]

Elsworth, S., Rose, J., & Date, O. (2000). New let´s go for EGB! Student´s book 2 with activity book. Harlow, England: Addison Wesley Longman Ltd. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and power. London: Longman. [ Links ]

García, S., & Tiberio, S. (1999a). Explorer starter. 3o ciclo EGB. Student´s book. Workbook included. Buenos Aires: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

García, S., & Tiberio, S. (1999b). Explorer one. 3o ciclo EGB. Student´s book. Workbook included. Buenos Aires: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

García, S., & Tiberio, S. (2000). Explorer two. 3o ciclo EGB. Student´s book. Workbook included. Buenos Aires: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

García, S., & Tiberio, S. (2001). Explorer three. 3o ciclo EGB. Student´s book. Workbook included. Buenos Aires: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

Gray, J. (2002). The global course in English language teaching. In B. David & D. Cameron. Globalisation and language teaching. London and New York: Routledge. Taylor and Francis Group. [ Links ]

Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. London: SAGE, in association with The Open University. [ Links ]

Kress, G., & Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading images. The grammar of visual design. London and New York, Longman. [ Links ]

Littlejohn, A., & Windeatt, S. (1989). Beyond language learning: Perspectives on materials design. In R.K. Johnson (Ed.). The second language curriculum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Llamas, A., & Williams, L. (2001a). English direct. Student´s book. Level 1A. activities included. N. P.: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

Llamas, A., & Williams, L. (2001b). English direct. Student´s book. Level 1B. activities included. N. P.: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

Llamas, A., & Williams, L. (2001c). English direct. Student´s book. Level 2A. activities included. N. P.: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

Llamas, A., & Williams, L. (2001d). English direct. Student´s book. Level 2B. activities included. N. P.: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

Llamas, A., & Williams, L. (2001e). English direct. Student´s book. Level 3A. activities included. N. P.: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

Llamas, A., & Williams, L. (2001f). English direct. Student´s book. Level 3B. activities included. N. P.: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

Llamas, A., & Williams, L. (2001g). English direct. Teacher´s book. Levels 1A and 1B. N. P.: Macmillan Heinemann ELT. Macmillan Publishers S. A. [ Links ]

McKay, S. (2002). Teaching English as an international language. Rethinking goals and approaches. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mugglestone, P., Elsworth, S., & Rose, J. (2000). New let´s go for EGB! Teacher´s resource book 1 and 2. Harlow, England: Addison Wesley Longman Ltd. [ Links ]

Pagliarini, M. I., & Assis-Peterson, A. A. (1999). Critical pedagogy in ELT: Images of Brazilian teachers of English. TESOL Quarterly, 33(3), 433-452. [ Links ]

Pennycook, A. (1994). The cultural politics of English as an international language. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Prodromou, L. (1988). English as a cultural action. ELT Journal, 42(2), 73-83. [ Links ]

Risager, K. (1990). Cultural references in European textbooks. An evaluation of recent tendencies. IN B. Dieter & M. Byram (Eds.), Mediating languages and cultures. Towards an intercultural theory of English language teaching. Clevendon and Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters Ltd. [ Links ]

Soars, J., & Soars, L. (2000). New headway. English course. Student´s book. Intermediate. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Soars, J., & Soars, L. (2000). New headway. English course. Student´s book. Pre-Intermediate. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Soars, J., Soars, L., & Sayer, M. (2000). New headway. English course. Teacher´s book. Pre-Intermediate. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Stratton, J., & Ang, I. (1996). On the impossibility of a global cultural studies: British cultural studies in an International frame. In D. Morley & K. H. Chen, (Eds.). Stuart Hall: Critical dialogues in cultural studies. London: Routldge. [ Links ]

Wallace, C. (2002). Local literacies and global literacy. In B. David & D. Cameron. Globalisation and language teaching. London and New York: Routledge. Taylor and Francis Group. [ Links ]