Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile no.7 Bogotá Jan./dec. 2006

Maria Helena Vieira Abrahão1

1Is an Applied Linguistics professor at the São Paulo State University (UNESP), located in São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil. She has a Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics from the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and is especially interested in foreign language teaching and language teacher education. She has supervised dissertations and theses related to these research areas.

mahevieira@yahoo.com.br

This paper presents results from an interpretive research which has analysed how language student-teachers construct their knowledge about language teaching and learning during pre-service teacher education. The study, embedded within the general frameworks of teachers’ thinking and socialization, involved language student teachers from a public university in Brazil.

Key words: Initial education, beliefs, language teaching and learning

Este trabajo presenta resultados de una investigación interpretativa que ha analizado cómo los profesores de lenguas construyen su conocimiento sobre la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de lenguas durante la formación pre-servicio. En el estudio, arraigado en los esquemas generales de reflexión y socialización de los profesores, participaron profesores de lenguas de una universidad pública en Brasil.

Palabras claves: Formación inicial, creencias, enseñanza y aprendizaje de lenguas

INTRODUCTION

There is evidence in educational and Applied Linguistics literature that the theoretical and practical knowledge developed in teacher education programs has little influence on the student-teachers’ subsequent practical activities (Zeichner, Tabachnic, and Densmore, 1987). This evidence points to the fact that teachers are highly influenced by their beliefs, which are results of their personal values and background knowledge.

There are also research findings which support the fact that student-teachers have the tendency to remember their own personal experiences as students which were acquired through their "apprenticeship of observation" (Lortie, 1975) and to construct their knowledge and teaching practice upon these remembrances. Beliefs, assumptions and knowledge acquired before the student-teachers’ entrance into teacher education programs work as mediators, filters of the input received by means of the theories and knowledge to which student-teachers were exposed to (Lortie, op cit; Zeichner & Grant, 1981; Tabachnic & Zeichner, 1984; Kagan, 1992; Roberts, 1998, among others) and, according to Kagan (op cit), implicit knowledge, values and practice tend to be stronger than the teacher education programs interventions, no matter the underlying theories of orientation.

In-service teachers also, according to Schön (1983), interpret and organize their experience by means of a repertoire of values, knowledge, theory and practice which they bring with experience, which he calls “appreciative systems”. These “appreciative systems”, highly investigated, have been named differently by distinct researchers such as teachers’ personal practical theories (Connelly & Clandinin, 1988); practical theories (Handal & Lauvas, 1987); teachers’ strategic knowledge (Shulman, 1986); practical knowledge (Elbaz, 1983) and BAK - beliefs, assumptions and knowledge (Woods, 1996).

No matter what teachers’ knowledge is called, there is something that seems evident: every student-teacher provides input to his university teacher education program and every teacher uses his teaching practice beliefs, assumptions, values, knowledge and experience which seem to exert a strong influence upon his/her theoretical and practical knowledge construction and development.

Besides those teachers’ socialization studies which evidence the weak impact formal education can exert to alter the apprenticeship of observation effect (Feimann-Nemser & Buchmann, 1986 and Pennington, 1990), we evidence others which argue that classroom experience is the main source of teachers’ knowledge (Claderhead & Miller, 1985; Shulman, 1986 & 1987). Almarza (1996), on the other hand, brings evidence in her study that student-teachers’ knowledge transformation occurred during a teacher education program and before the beginning of her/his teaching practice:

Thus, teacher education played a very influencial role in shaping student-teachers’ performance during teaching practice. It was knowledge learned in teacher education that became apparent during teaching practice (p. 72).

THIS STUDY

As an Applied Linguistics lecturer and foreign language teacher-educator at a public university in Brazil, I see it extremely relevant and necessary to study foreign language teachers’ knowledge construction in different stages (pre-teacher education; in-teacher education and post-teacher education) in order to enlighten the influence each type of knowledge brings to the theoretical and practical education and development of this professional. This research was conducted with this purpose. It is an interpretive investigation which aims at analysing the language teachers’ knowledge construction or, rather, beliefs, assumptions and knowledge that are brought by student-teachers to their education program; how these beliefs, assumptions and knowledge interact with the theoretical and practical content which are focused on the education program and how these different kinds of knowledge are manifested in their practice and produced during this stage. This research was guided by the following major research question and three minor ones:

How does language teachers’ knowledge construction occur while they are in university?

a) Which beliefs, assumptions and knowledge are brought by student-teachers to their university foreign language education program and what are the origins of these beliefs, assumptions and knowledge?

b) To what extent are student-teachers’ beliefs, assumptions and knowledge brought to university modified by the theoretical and practical reflections provided by the education program?

c) What kinds of knowledge are expressed (pre-teacher education knowledge or in-teacher education knowledge) or acquired by the student-teachers during their teaching practicum?

This research can be justified as follows:

1. For helping student-teachers to be conscious of their own beliefs, assumptions and knowledge which are tacit most of the time. This consciousness, even partial, may represent a first step towards their professional education and development. Helping pre-service teachers to reveal, think about and examine their own language and teaching conceptions is essential for educating them as reflective professionals (Clandinin, 1986);

2. The comprehension of how student-teachers’ knowledge is constructed in a pre-service foreign language teacher education program -although this research involved only six participants- is likely to provide contributions for teacher educators by helping them in their planning of strategies and content specification, so as to be able to develop the different kinds of knowledge in an appropriate manner.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Research Nature

This is an interpretive research which is characterised by the description and study of concrete and singular situations and by the consideration of the participants’ perspectives (Erickson, 1986; Bogdan & Biklen, 1998 and Silverman, 2000). There was no pretension of testing hypotheses, using pre-established categories or generalizing its results, although data collection and analysis were done systematically, which makes its results meaningful to other situations and contexts.

Context and Participants

This research was developed in a "Letter Course"1 of a public university in Brazil. Six student-teachers in their third year volunteered to be participants. Four of them were future teachers of English (Ali, Ka, Ma, and So) while two were future teachers of Spanish (Am and Fa)2

Third-year student-teachers were chosen for they had had no contact with formal theories of Applied Linguistics by the time this research began. This is an important fact since I wanted to uncover beliefs, assumptions and knowledge brought by these learners to their pre-service language teacher education program; more specifically, to the discipline Applied Linguistics-Foreign Language Teaching, which they take in the second semester of their third year of studies.

Ali, Ma, So and Fa had studied only in public institutions since elementary school. Am and Ka, on the other hand, had gone to public and private institutions. All of them had studied foreign language or languages outside regular schooling in private or public language institutes.

Four of them (Ali, So, Fa and Ka) had already started their professional activity by teaching English in private and public institutions while engaged in the project.

Research Phases and Instruments

During what I called phase I (first semester of 2001), we collected data in order to study the student-teachers’ beliefs, assumptions and knowledge by means of the use of a teachers’ belief inventory, adapted from E. Horwitz (1987). It consisted of a questionnaire, an autobiography and life history sessions.

During phase II (second semester of 2001), the interaction between the student-teachers’ beliefs, assumptions and knowledge and the theoretical and practical knowledge introduced and discussed in their teacher education program during Applied Linguistics classes as well as in weekly meetings with this researcher were studied. For data collection, student-teachers and this researcher kept reflective diaries and every weekly meeting was audio-recorded.

During phase III, which took place in 2002, when the student-teachers were involved in their teaching practice in the last year of their undergraduate course, their classes were video-recorded so that we could analyse the kinds of knowledge which were expressed in their practice. Reflective diaries were kept by the participants and semi-structured interviews were collected.

As far as analysis procedures are concerned, six case studies were first developed and later compared. All data were categorised and registers collected by different instruments and perspectives were considered.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

This study, which has its focus on teacher education, has characteristics of studies developed by two research frameworks, namely: research on teachers’ thought processes and on teachers’ socialization.

The first framework has as a main assumption the premise that teachers’ actions are influenced by mental processes. Teachers’ mental life is described and from this description researchers try to understand and explain how and why the observed professional activities are the way they are (Clark & Peterson, 1986). The same authors identify the following three categories in the teachers’ mental process: theories and beliefs; proactive planning and decision-making; and interactive decisions. The first one, which includes information, attitudes, values, expectations, theories, and assumptions about language teaching and learning, is considered the main source of teachers’ classroom practices.

The second one, which studies teachers’ socialization, is interested in investigating how beliefs, knowledge, attitudes and values are transmitted. For Feimann and Floden (1986), several socialization definitions have been used. For example, some see socialization as any change in the teachers’ behaviour. Others see it as the way new teachers acquire values and practices due to the interaction with more experienced professionals.

This research is directly based on Woods’ work (1996) in which he presents an integrated view of teachers’ beliefs, assumptions and knowledge (BAK), its features and evolution and its role in the teachers’ interpretive processes. According to the author, beliefs, assumptions and knowledge “do not refer to distinct concepts, but rather to points on a spectrum of meaning, although they have been treated for the most part as separate entities in the literature”. I share Woods’s definition of belief, assumption and knowledge for whom belief is “the acceptance of a proposition for which there is no conventional knowledge, one that is not demonstrable, and for which there is accepted disagreement”. Assumption, on the other hand, is defined as a “temporary acceptance of a fact (state, process or relationship) which we cannot say we know, and which has not been demonstrated, but which we are taking as true for the time being”. Knowledge is used by the author to refer to “things we ‘know’-conventionally accepted facts” (p. 195).

In this research, we analyse beliefs, assumptions and knowledge as an integrated construct for it is difficult or even impossible to categorize them separately.

THE RESULTS

Phases 1 and 2

A comparative analysis of the beliefs, assumptions and knowledge provided by the six student-teachers involved in this study suggested changes in a year’s period, after teachers’ exposition to the theoretical and practical reflections in the Applied Linguistics course and during the weekly group meetings.

Such changes could be mainly observed in relation to these categories: language, teaching, learning, learning a foreign language, most important factors which influence language learning and teaching, and teachers’ and students’ roles. Other categories which were salient and recurrent in the data of teaching a foreign language were an efficient language teacher, error, correction and evaluation. Coursebooks in language teaching and learning were practically unchanged as will be explained later in this paper.

In the first step of the research, the participants defined language as an instrument of communication, which suggests a structuralist view; as an instrument which leads to transformation (a functional view of language); as a product of social interaction, which reflects a socio-interactional perspective and as a social practice and power instrument, a discursive perspective of language. In the second step, the same conceptions were still present in the participants’ discourse, but the socio-interactional and discursive perspectives were more emphasized (see Figure 1).

As far as teaching is concerned, we could observe that in the first phase of this study, the student-teachers understood teaching as a transmission of knowledge, a traditional and positivist view that knowledge is something stable and finished. After a year, they seemed to have assumed a constructivist perspective, for which the individual has an active role as constructor of meanings from the world and from experience. The learner is considered someone who brings knowledge and experience to the classroom and it is through them that he/she makes sense of the learning experience (see Figure 1).

In the first step, learning was defined as the accumulation, acquisition, assimilation or absorption of new knowledge. Two of the student-teachers mentioned knowledge and experience upon which new knowledge is anchored, suggesting a cognitive view of learning, which focuses on the comprehension of the way human beings think and learn. Although the data suggested some of the students’ familiarity with a cognitive view of learning, we found that all of them still saw knowledge as something ready and finished. They did not seem to know clearly that knowledge is constructed and that each person, by means of his/her previous knowledge, assumptions and beliefs, constructs it in a particular way.

After a year, learning was conceptualized as construction of knowledge; as knowledge adaptation in a reflexive and critical way; as acquisition in a reflexive and critical manner; and as a process which involves autonomy and intellectual independence. One can observe that although they expressed themselves in different manners, which suggested that each one made a different interpretation of the experience and theories they were exposed to, the student teacher’s discourse reflected a constructivist perspective of learning.

Learning a foreign language was seen by the participants in a very traditional way, namely: learning a language is to learn grammar; it is repeating and practicing a lot; it is absorption of structures and vocabulary and it is absorption of the knowledge transmitted by the teacher. In the second step of the research, we could verify changes in participants’ perspectives for the focus was turned to language use, namely: learning a language is to develop the four abilities; a foreign language is learned when it is useful; and learning a language is experiencing real situations of language use. The analysed data pointed out that a traditional view of language learning was replaced by a communicative perspective.

As far as the factors which affect learning and teaching are concerned, in the first step the participants mentioned the following in their data: materials; students’ participation and involvement; relevance of the teaching content; adequate affective environment, motivation, and teacher-student interaction and teachers’ knowledge level.

In the second step, there was little change related to these opinions. They only left aside teachers’ knowledge level and kept intact the other factors. It is interesting to emphasize that in the first step of data collection the participants had had no contact with language learning and teaching theories and stated what seemed more favourable to them by considering their previous experiences as students or as language teachers, (Some of them had already started their professional life working in private language institutes.).

Their beliefs, assumptions and knowledge regarding teachers’ role in the first step were as follows: mediator of cultures; knowledge transmitter; classroom commander; collaborator, motivator, responsible for an adequate affective environment, and worried about students’ necessities and performances. They saw the students’ role as information receptor; mediator among students; learner and questioner; active and critical agent, collaborator and researcher.

It is interesting to observe that when defining teachers and students’ roles, some participants had already included in their discourse some contemporary positions attributing to the student an active role of knowledge constructor and the teacher the role of mediator-collaborator. This is mixed to traditional positions that could also be found as follows in their discourse: teacher as knowledge transmitter; classroom commander and the student as information and knowledge receptor. The presence of contemporary beliefs, assumptions and knowledge in the student teachers’ discourse is probably due to their experience as language students at the university in which the language classes are oriented by a communicative approach.

In the second step of the research the traditional conceptions about teachers and students’ roles were replaced by contemporary ones. They saw teachers as the ones who lead to knowledge construction, in other words, knowledge constructors - the ones who create conditions for learning; and mediators between the student and the new language and facilitators of knowledge. As far as the students’ roles are concerned, they characterized them as interagents who were co-responsible for learning; autonomous; efficient and were teacher conductors in the use of teaching strategies. These participants’ perspectives are coherent with their contemporary views of language learning and teaching presented in the second step.

After having provided a summary of the main modifications observed in the teachers’ discourse, we discuss origins of these beliefs, assumptions and knowledge in the following section.

The Origins

Mapping the origins of one’s beliefs, assumptions and knowledge is a very difficult if not impossible task. All that can be done is to raise hypotheses based on life history facts and reflections to get a glimpse of these origins. That is what we attempted to achieve with the data obtained from the student-teachers’ autobiographies and life history interviews. They will be presented here briefly.

From these data, I found that the six student teachers had brought good and bad remembrances from their elementary and secondary public schooling, where they had had the best and the worst of teachers. From these teachers they might have constructed part of the image of a good teacher they had by the time of the research, namely: a fair, delicate person who has good content knowledge, who is worried about students’ individualities and necessities, and who stimulates criticism and talents. The image they had of the English teachers they had studied with in public and private schools (Two of the student-teachers had spent a few years in private institutions.) was very negative. They had had no proficiency in the foreign language, their classes were very dull and they taught only grammar and translation. This opinion was also stated in the belief’s inventory they answered, in which they all disagreed with the following statement: English can be learned in a public school and English can be learned in private elementary and secondary schools.

They were conscious of the necessity of learning English and since they believed they would not learn it in regular schools, the six participants attended private language institutes where they experienced new forms of teaching and learning English, such as small groups of students in the classrooms, audiovisual resources, audiolingual and communicative methodologies, fluent teachers, colourful imported materials, etc. According to their impressions, this contrast made them reflect on the best routes to teaching and learning a foreign language and this reflection suggested that such experience was important for the construction of the knowledge they brought to university.

According to their narratives, they were good students in regular schools and loved literature and grammar, which they thought would be the focus of the “Letter Course”. They stated that they were very surprised to verify that grammar would not be the main focus of the course at university, once their professors adopted a communicative approach. During the period before the beginning of this research, after two years at the university, they were exposed to this teaching approach which included different resources and interaction organization for teaching. They stated that these two years had been extremely important for the construction of their perspectives of language teaching and learning, constructed by means of experience and little contact with theories.

Considering the student teachers’ conceptions and the realities of their school lives, we could conclude that although they had had little or no contact with formal theories regarding language learning and teaching until that first step, they had brought some contemporary perspectives with them that seemed to be possible by means of what Lortie (1975) calls “apprenticeship of observation”. That is what seems to have happened with their beliefs, assumptions and knowledge regarding the categories, namely, teaching a foreign language, error, correction and evaluation and coursebooks. Since their perspectives were contemporary and compatible with the theoretical-practical content developed in the education program, they were not questioned and were kept unchanged.

It is implicit in the previous paragraph that in order to have beliefs, assumptions and knowledge modified or replaced, questioning is necessary. Before questioning, however, it is indispensable to make them explicit. Education programs are responsible for helping the student-teachers uncover the construction they make of the world, namely: what they know; what they believe; and where and who they are so that they can construct meanings which are relevant to them (Williams, 1999). Horwitz (op cit) agrees with this position by saying that the first step for teachers’ development, since the methodology contents are interpreted through the beliefs system each one brings with him/her, is to uncover the beliefs. Teacher development is seen by the author as a continuous construction and reconstruction of knowledge, and I totally agree with her.

My results reinforce the theoretical position that beliefs are mutable when they are adequately approached (Rokeach, 1968; Burns, 1999; Barcelos, 2001; Johnson, 1992 and 1999; Roberts, 1998; Williams, 1999 and Cabaroglu & Roberts, 2000). In the next section, the methodology that was used to make the participants’ beliefs, assumptions and knowledge explicit will be presented.

Methodology Used to Elicit Beliefs, Assumptions and Knowledge (BAK)

The modification of part of the students’ beliefs, assumptions and knowledge probably occurred by means of the methodologies we used , which is similar to the one used by Johnson (1999, p. 39), and will be presented considering their different steps.

1) First of all, conditions were created so that the student-teachers could uncover their own beliefs, assumptions and knowledge by means of writing an autobiography, answering a questionnaire and a beliefs inventory adapted from Horwitz (op cit) and participating in life history sessions. The latter were audiorecorded and later transcribed by the student-teachers themselves.

2) Once their beliefs, assumptions and knowledge brought to the education program were expressed, or at least part of them, we tried to create conditions so that they could be examined in the light of what the participants knew intellectually and not just felt. This was done when the collected data were analysed by the student-teachers themselves.

3) By analysing their data and writing a report about them, the student-teachers were able to identify beliefs, assumptions and knowledge which they thought were conflicting.

4) In the second step of the project, the participants had the chance to get in contact with alternative ways of thinking and teaching, which was caused by contact with public and academic theories (Eraut, 1994), by means of readings and discussions in the Applied Linguistics classes and in the weekly group meetings, as well as the participants’ professional experience exchange, since some of them were starting the professional exercise in private language schools. It is interesting to emphasize that our meetings were oriented by a social-constructivist perspective (Williams & Burden, 1997). Knowledge was never seen as a universal truth to be transmitted to the students and to be implemented in their classrooms. The technical rationality model was avoided (Schön, 1983) and we tried to pursue a reflective approach (Wallace, 1991 and 1998; Zeichner & Liston, 1996, Zeichner, 2003), provoking the students to compare their personal theories to the public ones, constructing if it were the case, new personal theories.

Results of Phase Three

The analysis of the data collected in the third phase of the project, which had as its objective to analyse the beliefs, assumptions and knowledge expressed in the student-teachers’ practice during their practicum activities, revealed that the student-teachers’ practice reflected new perspectives that were constructed during the teacher education program which reinforces the importance of reflection upon theories and practices for the student-teachers’ knowledge construction.

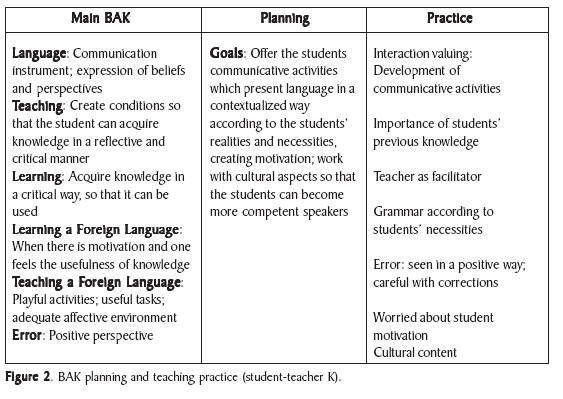

In figure 2, we can see that the participant Ka expresses the view of language as an instrument of communication and self-expression; teaching as creating opportunities for learning creatively; learning in general and learning a foreign language as a critical act, guided by usefulness and motivation and the importance of an appropriate affective environment, which can be reinforced by playful activities and an error positive view. In Ka’s planning, communicative and motivational activities were emphasized and these were selected according to the students’ interests and communicative necessities. Cultural aspects were to be discussed in order to get students more competent in the target language. As far as her practice is concerned, the following recurrent actions were observed: Interaction was valued in the classroom by the intense use of communicative activities which took for granted students’ needs, interests and prior knowledge; the teacher worked as a facilitator, was worried about the students’ motivation and treated students’ errors carefully in order to provide an appropriate affective environment for learning; also, grammar and cultural aspects were focused on according to the students’ communicative necessities.

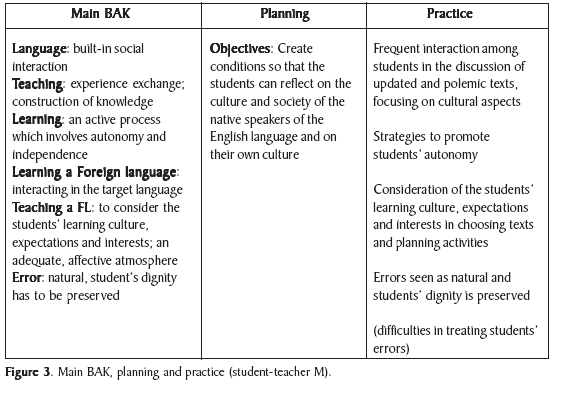

In figure 3 such coherence could also be observed. In his planning Ma expresses a sociocultural perspective of language, teaching and learning. To him we learn a foreign language by interacting in this language and when teaching a foreign language we must consider the students’ learning culture, their expectations and interests in order to create an adequate affective atmosphere in the classroom. He sees errors as a natural aspect of learning as well as students’ need to save face in the correction process. His objective for teaching was the following: to create conditions so that pupils could reflect on the culture and society of the native speakers of the target language and on their own language. His practice is characterized by the following recurrent actions: frequent interaction among students in the discussion of updated and polemic texts, focusing on cultural aspects; use of strategies to promote the students’ autonomy; and consideration of the students’ learning culture, expectations and interests in choosing texts and planning activities. Errors were seen as natural and students’ dignity was preserved in the classroom, although Ma confessed to feeling insecure as far as error correction and treatment were concerned.

Such coherence relating student-teachers’ BAK, objectives and teaching practice seems to have occurred due to the following aspects:

1. The student-teachers had had opportunities to discuss their beliefs, assumptions and knowledge over a whole year and seemed to be conscious of them.

2. The participants were completely engaged in the research project and understood that with more coherence, their teaching practice was better.

3. The participants had complete freedom in planning their courses and lessons. There was no imposition whatsoever.

4. The students were stimulated to reflect on their practice by means of keeping reflective diaries, in which they were invited to reflect upon the beliefs, assumptions and knowledge which supported their actions.

5. Some classes were videotaped and viewing sessions were organized so that student-teachers could discuss their practice with the researcher and their colleagues.

6. The weekly meetings focused on the participants’ practices and participants had the opportunity of sharing their experiences, anxieties and conflicts, which might have contributed to the later coherence in their work.

7. The participants’ practicum was informally evaluated by their colleagues and the researcher and formally by the Applied Linguistics and practicum teacher.

The rare incoherent procedures which characterized the participants’ practices were most of the time perceived and reformulated by them, which indicates their preoccupation with coherence related to what they said, planned and did.

We could also evidence moments in which the student-teachers manifested to be constructing knowledge from their practice. For example, when Ma questions the affective filter theory, saying that he had discovered from his experience with students that a tense state could be connected to the lessons and a permanent state of vigilance for new knowledge acquisition. This experience probably brought modifications to Ma’s BAK as well.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

We can conclude by stating that a pre-service education program, founded on a teaching and learning social-constructivist perspective (Williams & Burden, op cit), which started by offering conditions for student-teachers to be conscious of the beliefs, assumptions and knowledge they had brought to university (that created conditions for the interaction of these beliefs with theories and experience in a critical and provocative way and led to the construction of personal theories), offered elements for the construction of a classroom practice that was coherent with these theories, constructed throughout the education process.

Closing this article I bring the following two student-teachers’ words which evaluate the benefits of their participation in the described project:

“Besides having reflected about my beliefs and modified many of them, I can say that nowadays I feel more confident and prepared for the exercise of my profession, since I can explain my choices and consequences. Studying beliefs is very important: this knowledge makes the teacher a coherent professional who knows how to explain and justify his attitudes and keeps him far from being a dogmatic teacher.” (Final interview –student-teacher Ka)

“Considering the data from the autobiography I could find out that the student-teacher abandoned a passive attitude of absorbing the theoretical content to reflect upon his learning and teaching practice… Formal, structural aspects were replaced by communicative and affective ones… The reflections developed during the project allowed the participant to uncover these transformations, making them more explicit and concrete.”

(Research report, student-teacher M)

1 Pre-service graduation program for language teachers which lasts four years.

2 The first letters of the student-teachers’ names were used in order to protect their identities.

REFERENCES

Almarza, G. G. (1996). Student foreign language teachers´ knowledge growth. In D. Freeman & J.C., Richards (Eds.), Teacher learning in language teaching (pp. 50-78). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2001). Metodologia de pesquisa de crenças sobre aprendizagem de línguas: Estado da arte. Revista Brasileira de Lingüística Aplicada, 1, 71-92. [ Links ]

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (1998). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods (3rd ed.). London: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Cabaroglu, N., & Roberts, J. (2000). Development in student teachers´ pre-existing beliefs during a 1-year PGCE programme. IN: System 28, 2000, 387-402. [ Links ]

Claderhead, J., & Miller, E. (1985). The integration of subject matter knowledge in student teachers´ classroom practice. University of Lancaster School of Education. [ Links ]

Clandinin, D. J. (1986). Classroom practice: Teacher images in action. Lewes, Sussex: The Palmer Press. [ Links ]

Clark, M. C., & Peterson, P. L. (1986). Teachers´ thought processes. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 255-298). New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Connelly, M., & Clandinin, J. (1988). Teachers as curriculum planners: Narratives of experience. New York: Teachers College and Toronto, OISE. [ Links ]

Elbaz, F. (1983). Teacher thinking: A study of practical knowledge. London: Croom Helm. [ Links ]

Eraut, M. (1994). Developing professional knowledge and competence. Lewes, Sussex: The Palmer Press. [ Links ]

Erickson, F. (1986). Qualitative methods in research on teaching. In M.C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (pp. 119-161). New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Feimann-Nemser, S., & Floden, R.E. (1986). The cultures of teaching. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 505-526). New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Feimann-Nemser, S., & Buchmann, M. (1986). The first year of teacher preparation: Transition to pedagogical thinking. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 18(3), 236-256. [ Links ]

Handal, G., & Lauvas, P. (1987). Promoting reflective teaching. MiltonKeynes, UK: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Horwitz, E. K. (1987). Using student beliefs about language learning and teaching in the foreign language methods course. Foreign Language Annals, 18(4), 333-340. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. E. (1992). The relationship between teachers´ beliefs and practices during literacy instructions for non-native speakers of English. Journal of Reading Behavior, 24(1), 83-108. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. E. (1999). Understanding language teaching: Reasoning in action. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers. [ Links ]

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Professional growth among preservice and beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 62(2), 129-169. [ Links ]

Lortie, D. (1975). School teacher: A sociological study. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Pennington, M. C. (1990). A professional development focus for the language teaching practicum. In J. C. Richards & D. Nunan (Eds.), Second language teacher education (pp. 132-151). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Roberts, J. (1998). Language teacher education. Great Britain: Arnold. [ Links ]

Rokeach, M. (1968). Beliefs, attitudes and values: A theory of organization and change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Aldershot: Arena. [ Links ]

Shulman, L. (1986). Paradigms and research programs in the study of teaching. In M.C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 3-36). New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Shulman, L. (1987). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14. [ Links ]

Silverman, D. (2000). Doing qualitative research. London: Sage publications. [ Links ]

Tabachnic, B. R., & Zeichner, K. (1984). The impact of the student teaching experience on the development of teacher perspectives. Journal of Teaching Education, 35(6), 28-36. [ Links ]

Wallace, M. (1998). Action research for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Wallace, M. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Williams, M., & Burden, R.L. (1997). Psychology for language teachers: A social constructivist approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Williams, M. (1999). Learning teaching: A social constructivist approach-theory and practice or theory with practice. In H. Trappes-Lomax & I. McGrath (Ed.), Theory in language teacher education (pp. 11-20). Longman. [ Links ]

Woods, D. (1996). Teacher cognition in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K. (2003). Educating reflective teacher for learner centered education: Possibilities and contradictions. In T. Gimenez, Ensinando e aprendendo inglês na universidade: Formação de professores em tempos de mudanza. Londrina: Abrapui. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K., & Grant, C. (1981). Biography and social structure in the socialization of student teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 1, 198-314. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K., Tabachnic, B. R., & Densmore, K. (1987). Individual, institutional and cultural influences on the development of teachers´ craft knowledge. In J. Claderhead (Ed.), Exploring teachers' thinking (pp. 21-56). London: Cassel. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K., & Liston, D. (1996). Reflective teaching: An introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]