Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile no.8 Bogotá Jan./Dec. 2007

Looking at Cooperative Learning through the Eyes of Public Schools Teachers Participating in a Teacher Development Program*

Una mirada al trabajo cooperativo desde la perspectiva de los profesores de colegios públicos que participan en un programa de desarrollo profesional

María Eugenia López Hurtado** John Jairo Viáfara González***

**Universidades La Salle, Nacional de Colombia & Javeriana, E-mail: melh005@gmail.com Address: Calle 39F Sur No. 7 F-73 Bogotá, Colombia

***Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, E-mail: jviafara@yahoo.com Address: Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia. Avenida Central del Norte. Tunja–Boyacá, Colombia

An exploration of in-service public schools teachers’ implementation of cooperative learning forms the basis of this article. By means of a qualitative approach to research, two tutors in a teacher development program have studied how a group of English teachers set the conditions to create a cooperative learning environment in their classes. Additionally, they reveal the perceptions that these educators have of themselves as initiators who guide their students in this pedagogical experience. The analysis of information collected provides views about the role that teachers assumed and their concerns when organizing their classroom in order to experience cooperative work. Furthermore, teachers’ self-encouragement for professional development emerged as a fundamental issue when they implemented this approach in their institutions.

Key words: Cooperative work, cooperative group, cooperative class, cooperative workshop, cooperative learning

Una exploración de la implementación de aprendizaje cooperativo por parte de los maestros de colegios públicos fue la fuente esencial para escribir este artículo. A través de un enfoque de investigación cualitativo, dos tutores de un programa de desarrollo de maestros han estudiado como un grupo de profesores establecen condiciones para crear un ambiente de aprendizaje cooperativo en sus clases. Adicionalmente, ellos revelan la percepción que estos educadores tienen de ellos mismos como los iniciadores para guiar a sus estudiantes en esta experiencia pedagógica. El análisis de la información recogida proporciona las diferentes opiniones sobre el papel que los profesores asumieron y sus preocupaciones al organizar su aula para experimentar el trabajo cooperativo. Además, el mismoestímulo de maestros por el desarrollo profesional surge como un asunto fundamental cuando implementaron este enfoque en sus instituciones.

Palabras clave: Trabajo cooperativo, grupo cooperativo, clase cooperativa, taller cooperativo, aprendizaje cooperativo

Introduction

Group work as a pedagogical strategy has no doubt been experienced in a great variety of forms for students and teachers in language learning. There might be cases in which teachers set a structured plan to guide the functioning of groups as teams cooperating to achieve success, however, at the other end of the spectrum, students might work in groups without any specific principles which structure their interaction, being just aware of a task they are expected to complete in their own groups as soon as possible. In any case, creating conditions for making traditional group work a cooperative experience could be a challenging task for educators.

On studying the area of cooperative learning, we have found that a good number of people involved in teacher education in our country hold the belief that many of the principles of cooperative learning are now a reality in schools. Nevertheless, based on the survey applied to the group of public school teachers participating in this study, 70% have either not heard of this methodology or have not implemented it in their lessons, at least not while following a set of solid principles. Others have also talked about how difficult cooperation continues to be for many students in the given context. Owing to the specific challenges that implementing cooperative learning might represent in relation to different school subjects and contexts, we consider it relevant for us in EFL to see how this method is adjusted to public school realities.

Bearing in mind what has been said above, in this opportunity we have focused on examining what a group of in-service EFL public school teachers participating in the PFPD PROFILE1 reported about the implementation of cooperative learning in their classrooms. The examination entails, on the one hand, characterizing teachers’ procedures as they used this pedagogical strategy and, on the other, exploring what they perceived about themselves as initiators showing the path to their students.

The PFPD PROFILE (Professional Development Programs in the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language), which took place during 004 and 005 for teachers in Bogotá public schools, was the context for this study. These programs were financed by the SED (Secretaría de Educación Distrital) and developed at Universidad Nacional. The PFPD PROFILE has pursued as one of its aims the involvement of teachers in analyzing their theoretical principles and practices in the teaching of English as a Foreign Language while they work with their pupils in schools. To reach this objective, teachers participated in workshops about pedagogical issues. At the same time, along the different stages of the program, educators had the opportunity to integrate their updating in ELT (English Language Teaching) methodology with their experience as language learners and their research skills by means of an innovation or research project they developed in their specific settings.

The program counted on a team of tutors who not only guided different workshops in issues about pedagogy, language learning and research, but additionally supported groups of teachers in the planning and implementation of their projects at schools. The two writers of this article worked as tutors in the PFPD PROFILE. One of them participated in the program in 004 and 005 and the second one in 005. Both of them contributed to the development of the pedagogy module and guided several research or innovation projects that teachers implemented in their schools.

Literature Review

Experiences indicate that group work does not necessarily deal with cooperative work. According to Cohen (1986), group work involves working together in a small group so that everyone can participate in a task previously assigned. However, not all group work engages students in cooperative learning as Dörnyei (1997) points out.

Cooperative learning foundations are rooted in several motivational theories. To begin with, Slavin (1999), claims that a member who is part of a team can be encouraged to participate if he perceives that the group’s benefit constitutes also his/her own gain. One of the advantages of the motivational approach stems from the goal-oriented nature of teamwork that can be fostered in the members of a team. Some researchers have agreed that mutual support for procedures helps to achieve group objectives. Slavin, along with others such as Kagan (1994), has also stressed the role of cognitive theories in establishing the principles of cooperative learning. They pointed at Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s contributions as regards the idea that there is a better chance of learning taking place when people interact with each other. Another important tenet originates in social psychology from the concept of interdependence studied by Deutsch (cited in Kagan, 1994, p. 32 ) in relation to “people’s perceptions of how they affect and are affected by what happens to others”.

The previous theories closely relate to a set of principles for implementing cooperative learning environments that researchers have established. Johnson & Johnson (1999, pp. 38-46), for instance, point at the following ones: face-to-face interaction, positive interdependence, processing group interaction and individual accountability. Kagan (1994) has also observed positive interdependence and individual accountability as key elements in cooperative learning; however, he introduces two other principles, namely, equal participation and simultaneous interaction.

If teachers undertake the tasks of planning a cooperative learning class, along with the principles mentioned above, additional decisions need to be made. Johnson & Johnson (1999, p. 75) consider it necessary to determine how to integrate formal cooperative learning in which students constitute groups for several lessons, with informal teams. Additionally, the organization of groups according to specific criteria for the selection of members and the distribution of participants’ roles are key issues for the support of the principles of cooperative learning. Dörnyei & Malderez (1999, p. 169) state that teachers’ skills in managing groups in the EFL classroom to a great extend originate from educators’ knowledge of group dynamics.

Arranging and monitoring groups are part of the cooperative atmosphere that is fundamental to encouraging positive relations among members. Participants in a team might feel a sense of identity when they are assigned a role to perform since they assume new responsibilities, challenges or tasks in order to achieve a common goal (Millis & Cottell, 1997). Finally, planning cooperative learning experiences also has implications for certain aspects of lesson organization. Some of them include the determination of how cooperative work becomes part of the class stages, the supervision of students’ attitudes in order to gather information as well as to improve students’ work, and an enriching evaluation process (Johnson et al., 1999).

The following studies inform what participants in cooperative work experiences have said about their involvement with this kind of approach. Children’s reflections during and after working cooperatively with a team of partners to complete a science class project were part of the sources from which Muller & Fleming ( 001) drew their conclusions about their pupils’ learning process. This study not only confirms the benefits of cooperative learning mentioned in previous studies, but also points out difficulties that this methodology can bring. For instance, some students might end up doing all the work and certain group members might not contribute as others do. In relation to the teachers’ role during the development of this study, it is stressed that when teachers work completely on their own to implement cooperative learning, they might find the experience tough. Therefore, the provision of support for teachers who decide to work with this approach is highly recommended.

Other studies in the area of cooperative learning reveal how teachers made decisions in terms of grouping. Kutnick et al. ( 005) worked with twenty teachers from different areas at secondary schools in England to determine their thoughts and practices regarding the way they grouped their students in lessons. Results showed that teachers’ criteria for choosing specific groupings depended on the stages of the classes. Teachers believed in the benefits of teamwork but they did not prepare students to work cooperatively. Controlling pupils’ behaviour was closely related to teachers’ decisions about grouping. Individual learning received much more acceptance than the idea of interaction among students. Some teachers thought that small grouping was time consuming and they might lose control.

Regarding teachers’ implementation of cooperative learning, Siegel ( 2005) explored how a math teacher put this method into practice within a research-based model. The math teacher’s study revealed that the implementation of cooperative learning is not a simple task. Additionally, she found that in a constructivist perspective “one set of factors influencing a teacher’s use of cooperative learning will be his or her prior knowledge of teaching and experience as a teacher” (p. 346).

Cooperative Learning: A Component in the Pedagogical Module in the PFPD PROFILE

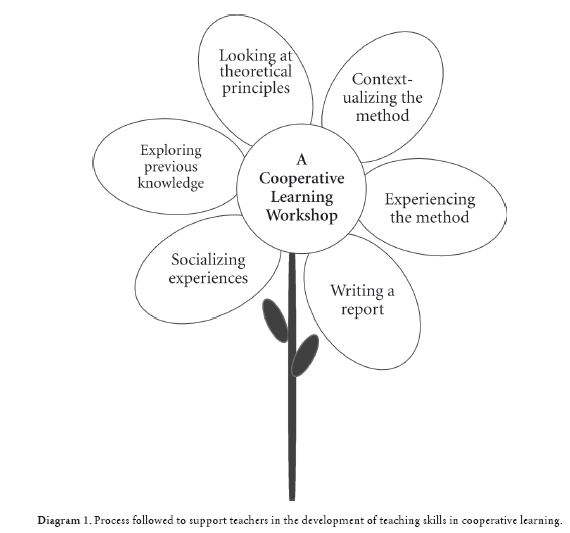

The cooperative learning workshop was implemented during the two years in which this study took place. The following diagram summarizes the process we followed during the program to support educators in their development of teaching skills in the area of cooperative learning.

This workshop usually took the form of three sessions. Two initial consecutive sessions explored teachers’ previous knowledge looking at the principles behind cooperative learning and involving teachers in experiencing the method.

In order to achieve this, a task was organized. The worksheet (See Appendix 1) supported the beginning of the workshop. Teachers read about the principles of cooperative learning and prepared a short presentation for peers. They wrote their summary in the petals of a flower that was completed as each teacher shared their conclusions with their peers. To fulfill their tasks, teachers worked in groups of four and performed specific functions (monitor, speaker, secretary and designer). As they worked in teams, the tutor demonstrated different aspects to be taken into consideration when dealing with cooperative learning. From the distribution of materials to particular ideas in giving instructions, reducing noise or coordinating what happened in groups, the tutor acted as a guide to illustrate possibilities. All the stages and roles of participants during the workshop served, at the end of the sessions, as points of analysis to be discussed and connected with participants’ experiences in their real contexts.

At this point, participants were encouraged to implement the approach and prepare a written report. They were also asked to be ready to share with their peers their impressions about what happened during their implementations. This task was developed in groups or individually. They were invited to get online support for their implementations. They could send drafts or express their concerns, and were given feedback and comments; we provided suggestions about authors that could support their planning, methodological tips and the introduction of philosophical reflection with their students. Furthermore, they were provided with bibliographical information to complement their knowledge.

After implementations took place, a socialization session was held so that teachers had the chance to share what they did and the results which were produced; they revealed their experiences, some of them successful and others not so fortunate, but all of them enriched each other since it was feedback coming from similar situations.

Setting Up a Research Framework to Explore In-service Teachers’ Implementation of Cooperative Learning

Context and Participants’ Profile

This study took into account what twenty male and fifty female public school teachers who participated in PROFILE during 004 and 005 reported regarding their experiences. They held Licenciatura degrees in Philology and Languages, Modern Languages or similar programs. Some of them worked exclusively in teaching English, but others worked in teaching Spanish, too. Their ages varied from the early twenties to the early fifties. They belonged to 34 public schools located around the city and implemented cooperative learning in secondary education. Approximately fifty percent of the teachers had heard of this approach before, but only thirty percent claimed they had used it. Educators had heard of it during their undergraduate programs or symposiums. The strongest reasons they gave for not having worked with cooperative learning before dealt with their belief that it was very complex or its association with ordinary group work. Among the total number of teachers, fifteen percent said they had used it but not systematically; they thought they lacked the theoretical background and had not implemented it with all the strategies and conditions required to guide their students in achieving common goals.

The lessons in which these teachers worked with cooperative learning included from forty to fifty boys and girls on average. Students who attended most of the schools lived in challenging socio-economic conditions. Based on teachers’ comments, violence, drug-abuse, mugging and earlypregnancy are some of the social problems in these contexts. A good number of them lived in single-parent families and started to work very early.

Method

This research is effected as a qualitative case study. In this light, the case study presented here is aimed at understanding the meaning of an experience on how a particular group of teachers makes sense of using cooperative work in their classes. According to Merriam (1988), a qualitative case study is “an intensive, holistic description and analysis of a single instance, phenomenon, or social unit” (p. 9). This method provided us with a rich view of the data collected in order to interpret and reflect on teachers’ perceptions towards using cooperative work in their classes.

Procedures for Data Collection and Analysis

Surveys

Seventy teachers were asked to fill in a survey (Bell, 1999) at the end of the program. All the questions were open. The survey started by asking participants about their favorite methodology during the PFPD program. Then other questions about their implementation, such as reasons for their preferences, duration of the implementation, their acquaintance with that methodology and results in their lessons, along with their recommendations for other teachers who might intend to use it, gave an overall picture of the approach teachers followed (See Appendix 2).

Teachers’ reports

We might associate this type of instrument to what Hubbard & Power (1993) call ‘students’ artifacts’. During the teachers’ cooperative learning workshop, they were asked to write a report on their implementation of this methodology in their classes. The guidelines provided by the tutors asked teachers to focus on three aspects. First, they contextualized the experience which involved describing duration, grade, group size and objective of the activity. Second, teachers narrated how they organized their lesson and the stages of the activity. Third, they described what they had observed during their implementation in relation to their experiences and to those of their students, feelings and opinions of this approach. They had the chance to work individually or in groups with teachers in their schools who were in the program. We analyzed 32 reports from teachers in 004 and 2005. These reports were not expected to be graded as such since teachers selfevaluated their participation in workshops.

Interviews

A semi-structured interview (Bell, 1999) was used to explore the teachers’ implementations of cooperative learning in their lessons. The base questions for the interview were basically the same used in the survey plus the ones that emerged during the process which provided an opportunity to expand their comments (See Appendix ). Twenty-one teachers were interviewed. They volunteered to answer and their answers were audio-recorded.

Field notes

Following Hubbard & Power (1993), we used field notes to record the comments that teachers voluntarily decided to share with their peers about their implementation of cooperative learning. We took notes each session in which this took place, recording as much as possible of what they said. These records represent the oral version of their written reports.

The data analysis in this study is based on a grounded approach; this approach invites the researcher to read the data several times to notice similar themes or patterns (Freeman, 1998). We wanted to analyze the data from surveys, teachers’ reports, interviews and field notes to identify the categories that emerged from that analysis.

We followed the principles of triangulation to provide credibility for our study. We took into consideration multiple methods for data gathering (Martin Denzin, 1978, as cited in Freeman, 1998). Furthermore our study involved more than one researcher; according to Janesick (1994), this is called investigator/researcher triangulation because it uses more than one investigator/researcher to gather data.

Characterization of Teachers’ Implementation of Cooperative Work in Their Classrooms

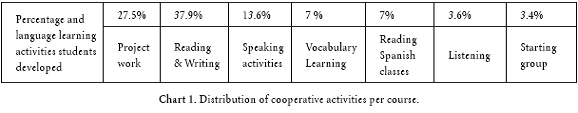

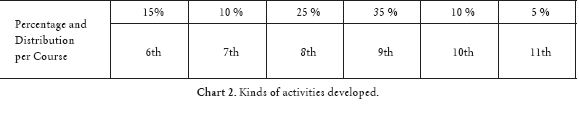

The analysis of the thirty-four reports submitted and shared by teachers in the same number of public schools in Bogotá, along with the teachers’ comments during feedback sessions, informed us as to how they organized the cooperative experience in their classrooms. The frequency of implementation of this approach in classes varied from one time, for the teachers who used it the least, to one semester, for the ones who used it the most. On average, the participants implemented it for approximately two months during the 10 months that they participated in the PFPD. The following charts reveal teachers’ preferences in relation to courses and kinds of activities when setting up cooperative work.

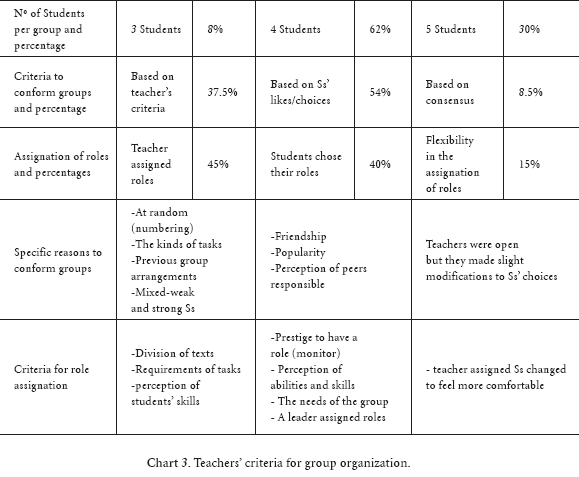

Group organization, as a key feature in cooperative learning, took a good amount of time from teachers. Several variables, such as the ones shown in the chart below, seemed significant at the time when the groups were formed.

Revealing Teachers’ Perceptions about Themselves as Guides in a Cooperative Learning Experience

When teachers implemented cooperative work in their classes, they continuously reflected upon the possibilities that this pedagogical strategy offered and upon their classrooms’ reality. The following findings describe in detail how they viewed themselves as initiators of cooperative work, showing the path to their students.

The Teacher as a Mediator in a Cooperative Environment

Guiding their pupils in learning how to work cooperatively required teachers to act as agents through which common efforts could be channeled. In achieving the previous role, teachers seemed to soften relations among their students, foster students’ expression of their ideas, and encourage reflection upon the meaning of cooperative learning. As an illustration of how teachers assumed the roles of mediators in their implementation of cooperative learning, an excerpt of a report prepared by a group of teachers is cited below. In this implementation, students were placed in groups made up of a leader, a materials monitor, a designer and a reading monitor. After they had worked together for a while, some of them started to act aggressively; they shouted and tried to fight. Teachers agreed that this type of behavior is common in the context of many public schools. The problem arose because students felt forced to do what their partners told them to do. After this difficulty started, teachers commented, “in this moment, the teacher acted as a conciliator and two of them came back to work with their group, the other two students definitely did not want to work, they did different things”. This situation relates to the most noticeable feature teachers remarked on their roles as mediators; they became similar to bridges for communication among students.

Information collected suggests that teachers had a tendency to be more flexible in their roles in order to facilitate cooperation not only among their pupils, but also between themselves and their pupils. They shared their “steering wheel” with their students so that they were not always in front of the class guiding others and monopolizing the opportunities for communication. In transferring authority to the groups, teachers showed their students that they were not the only person in the classroom who gave and had knowledge and they gave their pupils new possibilities for learning since sometimes students understood their peers better than teachers. This is reflected in the notes taken during a feedback session in which Aura’s comments were recorded. Aura was a ninthgrade teacher who worked in a school located on the edge of the city, where a high number of students have the characteristics of rural citizens. She said while using this approach she noticed how students could also be leaders. It was not always she who made decisions. Students made appropriate selections of team members since they knew their peers’ abilities. The teacher was not always in control and she felt more like a guide.

Additionally, teachers’ mediation to make cooperative learning a successful experience bore connections with the ways in which educators encouraged their students’ development of qualified work. There are several comments in which praise or rewards took on an important value for teachers. This is reflected in a report that three teachers wrote, to wit: after students had created articles cooperatively about different issues such as poetry, culture and sports, they were rewarded as the best works and were published in the school bulletin.

Closely related to the challenge that teachers took of assuming new attitudes towards their students, participants talked about their disposition in managing their feelings and emotions in coherent ways within a cooperative environment. They commented that usually, as the number of students in their classrooms is extremely high, they might become quite stressed when they try to handle all the managerial aspects to support the learning of 50 students or even more without any help. They frequently have to pay attention to the organization of materials, the clarity of procedures and the way students were using language, just to list some issues. When they started to use cooperative learning, they felt this method helped them to avoid becoming overstressed since they shared responsibilities.

During this experience, educators also faced the pressure of the policies they had to follow in their schools. A silent classroom, with students writing on their own and sitting in rows, was expected from many of them. Ernesto commented about his experience that:

I would like to contribute to the discussion with some points in relation to the school administration. When I started assigning cooperative work, students worked in groups; some of them worked, others came, others went around and they (the administration) told me off. ‘It seems you are doing nothing in your class; why aren’t your students quiet? Why aren’t they silent?’ The coordinator wanted to see the kids in lines, silent and writing; that’s for her a good teacher. These are retrograde ideas and one has to fight against them.

Though the teachers’ initial fear, caused by the noise in groups, worried them for a while, apparently their concerns tended to turn into relief as they gained more skills. On the whole, they mentioned that being more relaxed provided them with opportunities to look at students in greater detail and to solve problems which previously they did not know how to solve. Several participants remarked that students were not the only ones who showed more self-confidence during this experience. A good number of educators claimed that they felt more selfassured themselves.

As teachers acted as mediators, they noticed that their efforts brought another meaningful contribution to them; they knew more about their students and about their own teaching skills. Specifically, they increased their understanding in relation to their students’ need for more social abilities, their hidden talents and the way in which those skills could help others in the lessons. This reminded them that it was not only the teaching of English that was at stake in their EFL lessons.

The Search for Class Organization

While working with cooperative learning, teachers commented on the efforts that they made to arrange their classrooms as spaces where cooperative learning might take place; many times their job contexts seemed not to fit with the innovation they tried to carry out. For some educators, the lack of materials, the kind of desks or the number of students in classrooms became obstacles. Apparently, their first step to overcome this challenge was to become aware of their need to plan their lessons more systematically. Teachers considered that any plan to encourage cooperative learning strategies in the class would only have a good chance of working if circumstances were propitious. Among these conditions, they underlined preparing the lesson carefully in advance, taking into account possible difficulties, being alert to the need to reshape the lesson as this took place, and having enough resolution to keep on despite downfalls.

Specific curricular aspects that educators kept in mind when organizing this cooperative approach dealt with the clarity of objectives as well as topics, the specification of tasks, the organization of time, the availability of materials needed and the clarity in the rules of the game for students. Jorge was a teacher who decided to develop his research project on cooperative learning. He worked with students in 10th grade and when we asked him about his suggestions for other teachers who wanted to use cooperative learning in classes he commented:

I would tell them to use this strategy as a learning and teaching method. Nevertheless, what you have to do as a teacher and your commitment increases and this is so because you have to consider the organization of many aspects in advance. Something which you probably don’t do traditionally for your class… for example, resources and above all monitoring and providing feedback in relation to students’ responsibilities.

A great deal of participants’ planning involved their search for suitable possibilities to plan for both work with groups and work with the whole class. Facing this challenge was not easy because it implied a change in their traditional organization of students in the class space; teachers did not find it easy to break the traditional sitting in lines. However, as teachers experimented with cooperative leaning, they realized this was suitable for mixed ability classes, a characteristic of the large groups they usually teach.

As teachers work in preparing their teaching setting for cooperative learning experiences, they realized it was important to combine several methodologies and approaches in their teaching. Many of them said that they integrated project work and task-based learning with cooperative work since they perceived similarities and coherent principles to support students in their development of language-learning processes; guiding students in a systematic process such as writing by means of cooperative learning can enrich them a lot, they expressed. Jimena talked about her experience with two of her colleagues in an interview.

We integrated cooperative learning and Project Work. This is to say that the work we developed was geared towards the development of a project by means of cooperative learning. We designed some workshops based on clear specific tasks and everything was part of a process ‘till a final product was reached.

The planning of evaluation experiences in agreement with cooperative learning principles was a concern for many teachers too. They regarded evaluation as a shared task among teachers and students and looked for different alternatives in their assessment of pupils. Cooperative learning allowed teachers to open more to the value of self-assessment since students worked more in identifying their own weaknesses and strengths. Moreover, students’ constant monitoring of their peers’ performance, as well as their group reflection in order to achieve a specific task, made peer-evaluation a more spontaneous practice. Self and peer assessment seemed to make the teacher’s job in the area of evaluation more complete because they had more points of view as regards their students’ performance and attitudes.

Teachers’ Realization of the Need for Continuous Professional Development: A Link to Their School Community

The positive and negative results that teachers achieved while working with cooperative learning seemed to have encouraged them to look deeply at themselves as professionals in need of continuous improvement. To begin with, they questioned what they knew about this approach. In fact, several participants stressed at the end of the program that they were still lacking more knowledge and experience in working with cooperative learning; as a consequence of that, they showed willingness to obtain more information as well as to increase their skills in using this pedagogical strategy. Participants valued development programs not only because they studied theory and were encouraged to put it into practice, but also because they were monitored in their implementations by tutors. Regarding the previous aspect, Hector, an eleventh-grade teacher, said during the feedback sessions that reading the comments that his tutors had written in his report had made him aware of key aspects of his experience. He commented that for him theory had always been important but that now he thought it was secondary. It was not only theory but also practice that he needed to pay attention to.

Furthermore, participants remarked how, by means of their participation in the program, they moved from a pure experimental practice into a more documented work since they wrote about their processes. On the whole, educators considered that these kinds of courses gave them the support they needed to be more systematic and analytic in their teaching. In relation to her experience with cooperative learning, Rosa commented in an interview:

…being accompanied and supported, sometimes you need another person who can tell you let’s take into account opportunities, spaces and schedule… you sometimes are very relaxed on your own discipline and you do not set a suitable rhythm to work. When you have acquired a commitment with an institution and you feel they are by your side, you are more devoted in those kinds of things.

Teachers had the opportunity to experience cooperative learning first as learners in the program and then they carried it out with their students. Teachers were encouraged to try this method in their classes, thus, participants informed us that the TDP fostered their innovations. Their EFL classrooms were the school context where cooperative leaning took place in the first place, but teachers also transferred their new skills and used the approach in other classes, namely, in the Spanish ones. Additionally, this approach was also used when various activities for school were being organized. Cooperative learning went beyond the EFL classroom context since teachers saw a variety of opportunities at their disposal for helping themselves and others.

Teachers perceived cooperative work as a learning experience which took place not only among their students, but also among teachers in their institutions. Among their group of colleagues in the EFL area at their schools, it was possible for some educators to replicate the workshops that they had been part of in the TDP about how a cooperative lesson could be. That is to say, they could support their preparation of cooperative work experiences among themselves before putting them into practice. Likewise, it seemed for them that the possibility to have a bigger impact in their students related to how they teamed up with teachers in the same grade.

Conclusions and Pedagogical Implications

Cooperative learning as a pedagogical strategy, in which groups of students are guided to structure their work strategically to support each other in reaching common goals, does not seem to be implemented regularly by a large number of public school teachers. Group work without a clear structure for cooperation is widely practiced in the context of the population studied. Different factors, such as teachers’ lack of knowledge, confidence, specific logistic features of their job context and school policies, seemed to explain educators’ attitudes. Thus, the use of mainstream methodologies in EFL might pose some challenges for specific populations of teachers in our country. Further research in regards to these factors might contribute to what teachers themselves and teacher educators might plan to support their work with the methodologies they choose to try.

Characterizing teachers’ decisions in regards to their implementations of cooperative learning revealed their tendency to adapt the basic principles of this pedagogical strategy to their contextual needs and their previous teaching experiences. The great variety of options that we perceived in educators’ organization of groups, kind of classroom activities and combination of methodologies supports Siegel, 2005, p. 347. He concluded that professional development courses should include strategies to encourage teachers to describe their daily teaching practices as a way to foster the integration of cooperative learning in their work.

Teachers perceived cooperative learning as a methodology which in several respects shared similarities with other pedagogical strategies they had used in their efforts to support their students’ communicative learning of English. In this sense, cooperative learning seemed to be an ideal ally for taskbased learning and project work which shared tenets with communicative language teaching approaches. This, in turn, endorses the views of Arias et al. ( 2005) in relation to the experimental attitude that teachers need to adopt when working with this approach. Experimenting can facilitate the way in which cooperative learning spontaneously becomes a part of a teacher’s pedagogical strategies and so obstacles might be overcome.

The experience of incorporating cooperative methodologies in our classrooms opens up a rainbow of opportunities for teaching and learning. Teachers developed skills to conduct future cooperative experiences, encouraging their students to grow academically and to be society members who build new knowledge and experience together.

Teachers’ implementation of cooperative work seemed to provide them with a myriad of positive pedagogical outcomes which brought benefits for themselves and their students. Even though educators also encountered difficulties in using the approach, part of their learning process dealt with their awareness of how to overcome those limitations. Difficulties appeared as a natural part of the process which involved leaving aside the kind of traditional classroom work that hinders possibilities for innovation in aspects such as seating arrangement and assignation along with distribution of roles in the lessons. Other difficulties reported by teachers included how hard, on a regular basis, they found it to encourage students to assume genuine cooperative attitudes. They regarded the problematic context in which public school students often live as a potential reason for their pupils refusing to cooperate. Despite the previous vicissitudes, most participants accepted the challenge of innovating by means of this approach and tried to take the necessary measures to organize a cooperative classroom.

Providing for a genuine cooperative environment meant that the majority of participants had to assume a reflective attitude in considering what cooperation implied. Crandall (1999) underlines the fundamental role that teachers play in planning strategies to discuss with their students’ cognitive, social and learning issues in cooperative work. Using cooperative learning led teachers to consider and take actions about the importance of their roles as mediators among themselves and their students in establishing a cooperative environment. It is necessary to construct and develop cooperation abilities since it is not easy to change our mentality if, traditionally, we have been working in isolation.

Participants’ views about the relevant role of teacher development programs in their education implies that individuals and institutions supporting teachers need to seek opportunities to monitor and further support participant educators in their classroom innovations not only while the program takes place but, ideally, after it has finished.

Since participants perceived cooperative work as a necessary skill among colleagues in the same institution or different ones, they could become involved in networking. This kind of association might bring educators’ “emotional support and professional support and growth taking into consideration that personal and professional dimension interrelate” (Oliphant, 1996, p. 69).

* This paper reports on a study conducted by the authors while participating as tutors in two PROFILE Teacher Development Programmes, at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, in 004 and 2005. The programmes were sponsored by Secretaría de Educación de Bogotá, D.C. Code numbers: 3010 003905 ( 2004) and 30501006055 ( 2005).

1 The PROFILE Professional Development Programs in the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language were developed at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Foreign Languages Department, Bogotá.

References

Arias, J. et al. ( 2005). Aprendizaje cooperativo. Bogotá: Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. [ Links ]

Aldana, A. ( 2005). The process of writing a text by using cooperative learning. PROFILE, 6, 47-57. [ Links ]

Bell, J. (1999). Doing your research project. Philadelphia: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Cohen, E. G. (1986). Designing groupwork: Strategies for the heterogeneous classroom. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Crandall, J. (1999). Cooperative language learning. In Arnold, J. (Ed.), Affect in language learning (pp. 226- 245). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dörnyei, Z., & Malderez, A. (1999). The role of group dynamics in foreign language learning and teaching. In Arnold, J. (Ed.), Affect in language learning (pp. 155-170). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dörnyei, Z. (1997). Psychological processes in cooperative language learning: Group dynamics and motivation. Modern Language Journal, 8 , 482 -493. [ Links ]

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing teacher research: From inquiry to understanding. London: Heinle and Heinle Publishers. [ Links ]

Hubbard, R., & Power B, M. (1993). The Art of classroom inquiry. A handbook for teacherresearchers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Janesick, V. (1994). The dance of qualitative research design. In Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (Ed.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 209- 219). CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Johnson, D. et al. (1999). El aprendizaje cooperativo en el aula. Buenos Aires: Paidos. [ Links ]

Johnson, D. et al. (1999). Los nuevos círculos de aprendizaje. Argentina: Aique. [ Links ]

Kagan, S. (1994). Cooperative learning. CA: Kagan Cooperative Learning. [ Links ]

Kutnick, P. et al. ( 2005). Teachers’ understanding of the relationship between within-class pupil grouping and learning in secondary schools. Educational Research, 47(1), 1- 24. [ Links ]

Merriam, S. (1988). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass. [ Links ]

Millis, B., & Cottell, P. (1997). Managing the cooperative classroom. In Cooperative learning for higher education. Phoenix: American Council of Education. Oryx Press Series on HigherEducation. [ Links ]

Muller, A., & Fleming, T. ( 2001). Cooperative learning: Listening to how children work at school. The Journal of Educational Research, 94(5), 259- 265. [ Links ]

Oliphant, K. (1996). Teacher development groups: Growth through cooperation. ÍKALA, (1), 67- 86. [ Links ]

Peterson, S., & Miller, J. ( 2004). Comparing the quality of students’ experiences during cooperative learning and large-group instruction. The Journal of Educational Research, 97(3), 123-133. [ Links ]

Siegel, C. ( 2005). Implementing a research-based model of cooperative learning. The Journal of Educational Research, 98(61), 339-349. [ Links ]

Slavin, R. (1999). Aprendizaje cooperativo. Teoría, investigación y práctica. Argentina: Aique. [ Links ]

Slavin, R. (1988). Educational psychology. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]