Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Print version ISSN 1657-0790On-line version ISSN 2256-5760

profile no.8 Bogotá Jan./Dec. 2007

Tutorial Plan to Support the English Speaking Skill of an Inga Student of an Initial Teacher Education Program*

Plan tutorial para apoyar el desarrollo de la habilidad oral en inglés de un estudiante de Filología e Idiomas que pertenece al grupo indígena Inga

Deissy Angélica Velandia Moncada**

Universidad Nacional de Colombia, E-mail: davelandiam@unal.edu.co Address: Carrera 16 No.10- 0 Zipaquirá - Cundinamarca, Colombia

This paper reports on a case study consisting of the implementation of a tutorial plan as a way to support the improvement of the speaking skill of an Inga indigenous student who had difficulties learning English as a third language. This study reveals the similarities of the learning process of the student to a traveler’s journey. On the way, the student asks his tutor for direction and support so he can get to the end of his journey on his own. Likewise, it is described and analyzed how the student was helped to improve his oral communication skill in a more natural and meaningful way through tutoring sessions that incorporated principles of autonomous and task-based learning.

Key words: Tutoring, oral skills, autonomous learning, task-based learning

Este documento reporta un estudio de caso que consistió en la implementación de un plan tutorial basado en la metodología de aprendizaje por tareas, para apoyar el desarrollo de la habilidad oral de un estudiante indígena inga quien presentaba dificultades en aprendizaje del inglés. El estudio revela la similitud del proceso de aprendizaje del estudiante, con el camino de un viajero. En el trayecto el estudiante solicita orientación y apoyo de la tutora para llegar a su destino por sus propios medios. Así también, se describe y analiza la manera como se promovió y apoyó la producción oral de una manera natural y significativa por medio de sesiones tutoriales enmarcadas en el uso del aprendizaje por tareas y el aprendizaje autónomo.

Palabras clave: Acción tutorial, la habilidad oral, el aprendizaje autónomo, el aprendizaje por tareas

After years of concerted efforts, Colombian indigenous groups have achieved, to a certain extent, inclusion and recognition in different socio-political spheres. We are starting to value their wide range of cultural and ethnic diversity. Public universities of the country, aware of the continuing discrimination and disappearance of the Colombian native communities, have facilitated their desires to study and to get professional degrees. This has brought about different expectations and needs that have not fully been taken into consideration yet. For instance, universities lack official tutoring services and follow-up for students coming from these communities who may find themselves in learning distress and in need of assistance.

Regarding this situation and taking into account a teacher’s report that his indigenous student had difficulties with the English language –especially his oral performance, we decided to use a formula teachers have to enhance learning processes and to generate changes that go beyond the classroom, which is classroom research in languages. We aimed to enquire for the reason of his difficulties by describing and analyzing the features of his oral communication in English and to guide and support him by implementing a tutoring plan. In order to protect the identity of the student, we assigned him a pseudonym: Andrés.

Literature Review

Since in this study we aimed to understand an issue that had unique and singular distinctions, we started by finding out about the cultural, social and political background of the student’s community. After that, as a way to improve the teaching and learning process, we studied tutoring techniques and the task-based learning approach. We also examined the nature of speaking and its implications.

Inga Community

This community is located in the Department of Putumayo, in the Amazon Region (Arango & Sánchez, 004). The members descend from a Peruvian in-digenous group: the Kitchua. The community is divided into reservations. Andrés belongs to the Inga Reservation of Mocoa, whose current population is 609 inhabitants. Their native language is Inga but the community has almost lost it. Inga is taught in schools as a curricular subject and is mostly spoken by the elderly and adult members of the group. Young people usually understand it but cannot speak it fluently. Spanish is broadly spoken by everyone in the community. The Inganos believe in the everlasting bond between nature, life and spirit. They are respectful toward plants and the environment and have a strong sense of belonging.

As in others indigenous communities, Inganos are concerned about their representation in the political and social fields of the country and their presence in the universities is still low. They are also alarmed about the loss of their cultural uniqueness when they are to leave their communities to go to urban contexts in pursuit of professional education. Indigenous students frequently find it difficult to adapt to this different environment, a fact that increases the percentage of desertion. Tutoring programs that assist in-need students could be an answer to this crisis.

Tutoring and Autonomy

This aspect is of special interest since it is one of the foundations of the study. First, it must be highlighted that the tutor is to increase the confidence of the tutees, help them to learn autonomously, and assure that effective learning takes place. “Tutoring is a pedagogic and educational strategy that is provided to guide and assist students to achieve integral learning. It also intends to stimulate the development of skills so that the learning of their discipline advantages students. To sum up, tutoring seeks the enhancing of students’ abilities and the overcoming of weaknesses in their learning process” (Universidad Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora Del Rosario, 2000).

The effectiveness of the tutorials was also revealed by a research study done in the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in 1995 with students of a public high school who showed poor performance in the English class. Researchers implemented a tutoring plan for them. In this study, the researchers found out that students who were helped via tutoring showed themselves more confident, motivated and engaged in class. They also acquired positive learning strategies and, in general, performed better academically (Chirivi & Jiménez, 1995).

On the other hand, the role of the tutor is to promote learning processes by giving the students the tools to take responsibility for their own learning. A tutor is not supposed to tell but to make a student find answers. “Your job as a tutor is to eventually become unemployed... Actually, one of your best successes could be that a student NO LONGER needs your services” (Alves, 2002 ). The tutor has to get the student to find his/her own weaknesses. In this perspective, tutoring techniques are closely related to autonomous learning. One of the most important aims of tutoring is to promote autonomy and self reflection so that students become active in their own learning process. According to Scharle & Szabó ( 2000), becoming an autonomous learner is a gradual process achieved due to the changing of attitudes towards learning.

In this study, besides helping the student to become independent, we needed to understand what kept Andrés from being an effective communicator in English. For this reason, we acutely studied the nature and implications of speaking.

Oral Production

As stated by Brown & Yule (1983), the nature and functions of written language and spoken language are quite different; the former is distinguished by carefully planned explicit ideas, grammar and syntax. However, the latter implies that you have to decide on what to say next and how to state it while you are speaking. On the other hand, depending on the function, oral communication can be interactional (as in dialogues) or transactional (as in talks or monologs). Brown and Yule (Ibid., p. 25) remark that these functions entail different factors and abilities e.g. fluency, pronunciation, rhythm, listener’s feedback, oral comprehension, discourse structure, turn taking, etc. All these aspects, among others, may affect the organization of the speakers’ utterances and the information communicated.

Bygate (1997) considered the differences between native oral production and EFL learners’ oral production. He asserts that even when native speakers are believed to have an impeccable oral performance, they may also apply strategies to overcome time constraints and other factors that the nature of oral production involves. Some of these strategies are hypostasis, parataxis, ellipsis, formulaic expressions, time creating devices and compensation strategies. On the other hand, EFL students more likely may use achievement and reduction strategies. Achievement strategies involve guessing, paraphrasing and cooperation. Guessing occurs when a student, having some knowledge of the operation of the language, invents, “foreignizes” or creates words. The learner paraphrases when, instead of using the exact word, he gives its definition, an example, or, he/she subordinates it (lexical substitution strategy and cirlocution). Finally, examples of cooperation strategies are miming, pointing, eliciting/asking for help from the interlocutor.

Reduction strategies happen when students definitely cannot find a way to express an idea; so, they decide to either communicate an imperfect message or communicate a message other than the one intended initially (a message that the speaker finds easier to manage). These strategies mentioned here should be considered when analyzing and assessing oral communication. Students should recognize them as positive aids to avoid resorting either to the L1 or silence. Nevertheless, students should aim to get to a level where they do not need the aids as often. Besides, EFL teachers should also be conscious that to expect perfect oral performance from an EFL learner is unnatural and irrational.

These ideas related to autonomous learning, tutoring and oral skills let us understand Andrés’s difficulties in oral production and help him overcome them better.

Research Questions

The leading question for this research project was How can I effectively help and support an indigenous student to cope with his oral communication difficulties in English with tutoring? From this question, two secondary questions emerged: What are the features of a tutorial plan, which aims to enhance the oral skill of the student? and What are the features of his oral production during the tutoring sessions?

Researh Method

This study is framed in the qualitative research paradigm. This study has a dual nature. On the one hand, it is a case study given that it describes the happenings within a certain group of individuals in a specific context (Wallace, 1998). A comprehensive and exhaustive study of the learning process of the student and the features of his speaking performance would give us a holistic view of the factors affecting his oral production. On the other hand, this study shared principles with action research since it aimed to take part in this problematic situation by identifying the problem, reflecting, making decisions and taking actions (Kogan, 004). In this study, I, as the researcher, played a mixed role: one as an observer-researcher and one as a tutor.

Context

The B. Ed. In Philology and Languages (English, German or French) is a curricular program provided at Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogotá. This university grants members of indigenous communities of the country the opportunity to study a professional career through the Programa especial de admisión para bachilleres miembros de comunidades indígenas (Special admissions program for high school students who are members of indigenous communities). An important number of indigenous students have benefited from this program since it was implemented in 1986.

Description of the Participant

Andrés was a second semester student of the B. Ed. in Philology and Languages, English. He had to repeat the English Basic I course (equivalent to a pre-intermediate level) because he did not fulfill the requirements to pass to the next course. His teachers identified some difficulties mostly in the areas of grammar, speaking and listening. In this study, we focused on his oral performance whose main features were hesitation, use of Spanish or Hispanic constructions and difficulties organizing ideas and getting the message across. However, his attitude towards the language and the tutoring plan was very positive, showing commitment, interest and enthusiasm.

He is a member of the Inga community of Putumayo. His close family remains there. His first language is Spanish; he understands and speaks Inga fairly well. He uses it mostly when speaking to his grandparents, aunts and uncles. He started to study English in secondary school two hours a week where the teacher barely had communicative activities in the class.

Data Collection and Methodology

The data came from different sources, a tutee survey, a teacher’s survey, direct observation, and a Follow-up Format. This study was conducted from March to November, 006. The first step was to carry out the surveys with Andrés and his current and previous teachers in the university (four teachers in total) to become aware of the problem and state of the art. The tutor-researcher observed Andrés’s oral performance in the communicative tasks and recorded details in the follow up format as they happened in the tutoring session. At the end of the session, the student reflected upon his learning process and strategies and recorded his thoughts in the follow-up format.

Pedagogical Design

Taking into account the report of Andrés’s past and current teachers in English Basic I course, the decision made was to focus on assisting the student to enhance his speaking skill and to complement the tutoring by helping him to work on his learning strategies and autonomy. The tutoring sessions were arranged twice a week for one and a half hour each.

The first part of the tutoring session was based on task-based learning (TBL) in order to give the tutee the opportunity to use the language creatively and spontaneously and to reflect meaningfully on its use. The features of the TBL approach by Willis (1995) were appropriate for the purpose of this part of the tutoring since it focuses on the achievement of an outcome. The completion of the tasks was done in three stages or cycles: Pre-task, when the topic and instructions were given. The task cycle, when the student planned, developed and reported the task. And finally, the language analysis cycle, that included a reflection and practice of the language used and its features.

The second part of the tutoring session focused on the methodology of the learner’s autonomy as it provided Andrés with important and resourceful methods to approach and reflect on language learning. Andrés was asked to self-evaluate his performance in the session and in his regular classes. With the guidance of the tutor he stated his weaknesses and strengths and committed himself to put into practice on a regular basis some action plans.

Data Analysis

The data was gathered, analyzed and validated to ensure reliability. The validity was confirmed with the method of triangulation. The data came from surveys, direct observation and the follow-up format which was complemented with the tutee and tutor’s thoughts and reactions towards the process being carried out. Thus, the researcher has a general view of the perceptions of all the participants involved in the process (teachers, tutee and tutor-researcher).

The teacher’s surveys were a key instrument to identify André’s weaknesses and strengths. His teachers agreed that his oral performance in class was not satisfactory due, in part, to poor previous preparation in the language. They stated that he required assistance and extra work. They also answered that the highest priority was helping the student to improve his speaking, pronunciation, grammar and listening skills. On the other hand, this survey helped to rule out the possibility of the student being affected by affective factors. Teachers stated that he showed himself to be a confident, hard-working and motivated student, attitudes that were confirmed during the tutoring sessions.

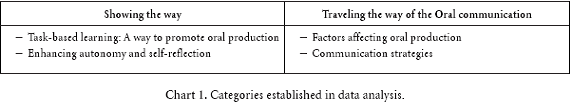

As for the analysis of the data collected by observation, journals and the student survey, we established the following categories. Each of them are divided into two.

Showing the way is a metaphor that implies what we intended to achieve through tutoring, which included equipping Andrés with the necessary tools to develop and improve his oral production and language learning autonomy. The first subcategory, Task-based learning: A way to promote oral production tells us how TBL was a useful methodology when trying to involve the student in meaningful tasks that help him to recycle, extend, create and self-monitor the language he was using. Most importantly, it reproduced the way the student learnt Inga. Andrés stated that learning Inga was easier given that at the age of 8, he had lived for a long period of time in a community where Spanish was barely spoken.

He also took Inga classes in the primary school where it was taught through stories and was usually connected to other subjects such as science and religion.

During the tutoring sessions, it was clear that by trying to achieve the goal of the tasks, Andrés interacted creatively, naturally and spontaneously. He was no longer worried about “correct” grammar but about getting the message across. During the tasks, the tutor let Andrés speak freely but wrote down grammar or pronunciation mistakes so, in the second part of the session, they could discuss the problems. This helped the student not to feel intimidated or prevented to express his ideas. The student was also assigned listening to some audio books and commenting on them in the tutoring sessions. He was also given the corresponding reading, which provided him with language patterns and vocabulary. In a short time, the incorporation of new vocabulary, pronunciation and expressions from the reading and audio was evident.

The continuous evaluation of the whole process allowed us to make decisions about learning strategies, study skills, learner preferences, etc. at the appropriate time. The discussions of the learning process taking place in the second part of the sessions revealed big advantages: the student increased his autonomy and self-reflection. For instance, he was aware that responsibility, commitment and work outside of class was vital in order to achieve real progress. In every session, the tutor guided the tutee through activities and discussions to reflect upon his own performance and progress. For instance, in the early sessions he stated:

“In this tutorial session, I realized I still have problems with being more confident, and take risks to talk without fearing of making mistakes. So I commit to participate and interact more in classes and start using a monolingual dictionary”.

Our second category, trajectory to the oral communication, refers to what is involved and implied when speaking. We aimed to describe and analyze features of Andrés’ oral production. Bearing this in mind, we established two main issues to be taken into consideration: The factors affecting oral production and communication strategies. Throughout the sessions, some factors that interfered with communication were evident. At the beginning, Andrés had difficulties applying basic grammar rules at the moment of speaking even when he was aware of their existence. He used to void the auxiliaries in the questions and to structure his utterances with the wrong word order.

In addition, he lacked understanding about informal and formal ways to express ideas; he was likely to use informal forms and chunks of language such as “yes” instead of “yes, I do” and “what?” when asking for clarification. Andrés presented some pronunciation problems, especially with the following phonemes: /ð/ /æ/ /?/ /e/ and in the final position of the words the phonemes: /?/ /p/ /v/ /z/. The reason for this, almost certainly, was the lack of these phonemes in Spanish or Inga. In order to get the student to pronounce better, we decided to start practicing isolated phonemes, phonetic patterns, linking, assimilation, etc. We used the book “Ship or Sheep” (Baker, 1997) and the “Sky pronunciation Suite” Software.

Another factor that characterized the student’s oral communication was the use of Spanish patterns. Andrés had a tendency to do direct translations from Spanish rather than looking for an equivalent meaning. For instance, he said “the Sundays” instead of “on Sundays”. In the survey, Andrés answered that he frequently tried to translate expressions from Spanish and that he found it difficult to think in English. He needed to internalize the target language and become aware of its features, but his reduced contact with English would not allow him to master the language.

However, as time passed, Andrés showed great progress. He frequently built complex utterances (subordinating) and started applying strategies to make communication flow. That is why a second subcategory of analysis was established: Communication strategies. These strategies largely determined the success of the tutee; they were used in order to compensate for his imperfect mastery of the language when faced with a communicative task. Based on Bygate’s (1997) analysis of communication strategies, we could conclude that he recurrently used time creating devices, such as hesitations, false starts, pauses, repetitions. The following is a sample of this occurrence:

Tutee: mmm… Fred don’t... don’t... (Self-monitoring) doesn’t have… he doesn’t have… (Hesitating and pausing) what do you say..? (Tutor interrupts)

Tutor: How do you say?

Tutee: Yes… How do you say: rencor? (Follow-up Format Nº 16, October 0th).

In this case, while Andrés was trying to structure a correct sentence and remember the story, he self-monitored his utterances. As one can discover, he was also using a cooperation strategy in asking his interlocutor for the translation of “rencor”. In occasions, being aware of the morphology of the target language, the learner made up or translated words from Spanish. For instance, he used “familiars” to mean “relatives” or “What more?” as opposed to a more appropriate English expression “What else?” The progress of the tutee was also evident when he avoided resorting to Spanish but tried to find a way to express himself even taking the risk of making mistakes.

We also took into consideration that according to Brown & Yule (1983), long transactional turns like retelling or reporting a story might be more demanding even for native speakers than interactional turns. In the tutoring, Andrés was guided to be able to manage both situations. For instance, every week he had to listen to a chapter of an audio book “William Wilson” by Edgar Allan Poe. He was also given the book with an easier version of the story so he could understand the audiobook better. In the tutoring, he was to retell the chapter of the story he had listened to in the week so he had the opportunity to work on strategies to manage transactional turns and it was also a good way to reproduce the way he had learnt Inga in his primary school.

Conclusions

We could see that the personalized environment created in the tutoring sessions allowed Andrés to be more confident and let him progress at his own pace, according to his specific needs. In addition, as opposed to the regular classes, the tutoring was a pressure-free activity in which the student did not worry about grades.

Tutoring also helped Andrés to take responsibility for his learning process. The learner progressively discovered a great deal of “magic wands” for language learning. Among the most important are self-reflection, selfevaluation, learning strategies, setting of goals and action plans. In the end, these tools became essential for the learner as he realized they enhanced his ability to learn the language.

The findings obtained in this research proved that TBL and autonomous learning are suitable and efficient methodologies as they helped the tutee to shed his inhibitions and gradually started turning him into a fluent communicator. During the tutoring sessions, the learner was encouraged to communicate orally without focusing on syntactic and grammar accuracy but on getting the message across. Although shortcomings of vocabulary, pronunciation and grammar were encountered during the tasks, with the tutor assistance and increased exposure to the language, the learner progressively started to internalize the language and felt more confident to use it spontaneously and creatively. For this reason, the use of communication strategies was more evident towards the end of the tutorial plan, as the student started to get engaged in meaningful communicative tasks and employed more frequently communication strategies in order to achieve the goal. Although communicative strategies are short-term solutions, as soon as the student attains a higher level of mastery of the language, he starts reducing its use.

The analysis of the features of Andrés’s oral production indicated that his mother tongue, Spanish, (and probably Inga) was interfering with the learning of English. He used to transfer language patterns from L1 and was inclined to translate from Spanish into English instead of thinking in the language. His difficulties with the language would be the result of several aspects. Firstly, the way in which he was meant to acquire the English language was artificial as opposed to the way he had learnt Spanish and Inga. Secondly, his previous preparation in the language was lower in relation to the one of the majority of his classmates and for teachers the class is not an appropriate setting to give individual assistance for students in-need. Thirdly, Andrés was not used to self-monitoring his oral performance and in general his use of the language.

This experience made us reach the conclusion that tutors can assist the oral production and language learning process by promoting learner’s autonomy and language learning strategy awareness and use. Likewise, the tutoring plan complemented the learn. ing process originated in the classroom. Nevertheless, there is a long way ahead and Andrés needs to continue by himself.

Pedagogical Implications

As a result of this teaching assistance experience, we were able to determine that lessons focusing only on vocabulary, grammar or pronunciation do not benefit a student with low academic performance. On the contrary, they would benefit more from lessons complemented with notions on learning strategies, communication strategies, study skills, and learner autonomy. Bearing this in mind, the basic course’s teachers have a huge responsibility to be aware, understand and follow up each student process so that they can detect difficulties at the right time and help students to determine an action plan to overcome them.

We also need to recognize the need of a tutoring program in the Foreign Language Department of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. The University should guarantee the integral education of students by providing help for those who are in academic disadvantage.

Further Research

This study raises a few queries that remain unstudied but could be considered in further research. In Colombia, little attention has been given to multilingualism due to the expansion of globalization; some members of indigenous communities are using three or more languages; Spanish, their indigenous tongue and a foreign language. This multilingual process may present very interesting challenges and implications for our society which we are not aware of yet.

Likewise, there is quite a deal of studies about the Inga Community of Sidmundoy but very little research has been done on the Inga Community of Mocoa. This aspect made it difficult to corroborate possible interferences of Inga in Andrés oral performance. Equally important, we need to study further repercussion of the role of language teachers as tutors who promote learners´ autonomy beyond regular classes. These unexplored fields are also worth studying.

* This is a report of a monograph project to opt for the degree of B. Ed. in Philology and Languages – English. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2006.

References

Alves D. ( 2002 , December). Tutorial and Academic Skills Center DeAnza Collage. Retrieved May 20 , 2006, from http://faculty.deanza.edu/alvesdelimadiana/stories/storyReader$29/ [ Links ]

Arango, R., & Sánchez, E. ( 2004). Los pueblos indígenas de Colombia: en el umbral del nuevo milenio. Bogotá: Departamento Nacional de Planeación. (pp. 33-34). Retrieved June 14, 006, from http://www.dnp.gov.co/archivos/documentos/DDTS_Ordenamiento_Desarrollo_Territorial/3g16librocapitulo8.PDF/ [ Links ]

Baker, A. (1997). Ship or Sheep? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Brown, G., & Yule, G. (1983). Teaching the Spoken Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Bygate, M. (1997). Speaking. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Chirivi, R., & Jiménez, M. (1995). Ventajas de un plan tutorial ofrecido a estudiantes de secundaria que presentan un bajo rendimiento en inglés: estudio de caso. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [ Links ]

Cohen, A., & Fass, L. (April 2001). Oral language instruction: Teacher and learner. Beliefs and the reality in EFL classes at a Colombian university. University of Minnesota. Retrieved March 15, 2006 from http://www.carla.umn.edu/about/profiles/CohenPapers/cohen_paper2.pdf/ [ Links ]

Kogan, L. ( 2004). El lugar de las cosas salvajes: paradigmas teóricos, diseños de investigación y herramientas. Espacio Abierto, 3(1). Venezuela. Retrieved July 0, 006, from http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/redalyc/pdf/122/12201302.pdf/ [ Links ]

Scharle, A., & Szabo, A. ( 2000). Learner autonomy: A guide to developing learner responsibility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sky Pronunciation Suite. ( 2000). Sky Software House Universidad Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario. ( 2000). Política de programa de tutoría. Comité Coordinador de Tutores. Bogotá. [ Links ]

Wallace, M. J. (1998). Action research for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Willis, J. (1995). A framework for task-based learning. Essex: Longman. [ Links ]