Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile no.8 Bogotá Jan./Dec. 2007

Devising a Language Certificate for Primary School Teachers of English

Elaboración de una certificación lingüística para profesores de inglés en la escuela primaria

Marina Bondi* Franca Poppi**

University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy, E-mail: bondi.marina@unimore.it, E-mail: poppi.franca@unimore.it Address: University of Modena and Reggio Emilia. Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia. Largo Sant’Eufemia, 19. 41100 Modena, Italy

This paper sets out to examine how the Common European Framework of Reference can be employed as a useful tool for the purpose of devising a language certificate meant to assess the competence needed for effective teaching at the primary school level. To this end, the B1 level descriptors of the CEF have been re-written so as to make them correspond, as closely as possible, to the abilities actually displayed in the context of primary language teaching and they have also been referred to three different contexts of use: classroom management, professional self-development and language awareness. A tentative draft of one of the parts of the certificate meant to assess oral comprehension will be shown as the final step of a process which started with the definition of the profile of the foreign language teacher.

Key words: Language proficiency certificate, descriptors, Common European Framework of Reference, foreign language teaching in primary schools

Este trabajo se propone explicar cómo se puede emplear útilmente el Marco Común de Referencia Europeo (MCRE) en la realización de una certificación lingüística que atestigüe las competencias necesarias para una enseñanza eficaz y eficiente en el ámbito de la escuela primaria. El análisis dará cuenta de cómo se han modificado los descriptores del nivel B1 del MCRE, para que se correspondan lo más fielmente posible con las habilidades utilizadas en el ámbito de la enseñanza de una lengua extranjera en la escuela primaria, con referencia a tres ámbitos de uso distintos: la gestión de la clase, el propio desarrollo profesional y la conciencia lingüística. Se mostrará un esbozo de una de las partes de la certificación lingüística, destinada a evaluar la comprensión oral, para ilustrar el desarrollo de un recorrido que, a partir de la reescritura de los descriptores del MCRE, lleva además a configurar un perfil del docente de un idioma extranjero en la escuela primaria.

Palabras clave: Certificación de las competencias lingüísticas, descriptores, Marco Común de Referencia Europeo, enseñanza de un idioma extranjero en la escuela primaria

Introduction

Several initiatives have been implemented in the last ten years for the purpose of extending the teaching of foreign languages to primary age pupils either to increase the time available for the first foreign language or to facilitate the introduction of a second or third in the secondary stages of schooling. The European Union in particular has undergone a process of gradual introduction of foreign language teaching at primary level in many of its countries, as can be seen from surveys of current research1 and as clearly highlighted by the findings of a report published by the European network, Eurydice, and funded by the European Commission, which sets out the key figures on language teaching in Europe2 .

On the whole, there has been an insufficient number of trained language teachers available to cater to this new demand, especially in primary schools, and many countries have started a reflection on the specific features of the language competence required of primary teachers. This has initiated a policy of national in-service training courses for practising primary teachers, as illustrated by the European Profile for Language Teacher Education, a document which deals with the initial and in-service education of foreign language teachers in primary, secondary and adult learning contexts and offers a frame of reference for language education policy makers and language teacher educators in Europe.

There has been great variety in the kinds of policy, strategies and models of provision of both foreign language teaching at primary level and the types of training on offer, with different entry points and requirements for existing language competence. Some countries have emphasised process rather than outcome, others have focused on listening and speaking and avoided reading and writing. Some have trained specialist, and peripatetic language teachers, others generalist primary teachers3.

In Italy, the teaching of a foreign language at primary level was introduced in 1985 and, in 2004, it was extended to all the five years of primary school, with English being the language which is most widely taught. The Ministry of Education has organised national in-service training courses for practising primary teachers, who have thus been encouraged to add a foreign language to their repertoire of teaching subjects or skills The most recent courses have focused on the English language only and are meant to help primary teachers reach the B1 level of the Common European Framework of Reference4.

The B1 level is in fact considered5 the minimum acceptable level of competence needed to teach a foreign language in primary schools. It is also regarded as particularly important, within the Italian national education system, to define a common standard for training programmes that are organized locally. This normally requires the definition of a common core of abilities and specific competences that can be officially certified and recognized all over the country.

After the end of the first courses, it was decided to assess the teachers’ acquired competence by means of the Preliminary English Test (PET), concerning the level required for the teaching of English. However, it was soon clear that this certificate, though appropriate for the level, covered a wider range of skills than those strictly needed by primary language teachers and had a different, more general target in mind, while overlooking issues which were especially relevant to primary teachers. It was thus decided to try and devise a specific certificate which could assess the teachers’ competence in those areas and skills which were actually the most important ones for the purposes of primary school teaching.

This paper will report on the rationale behind and development of the CEPT (Certificate of English for Primary Teachers), jointly developed by the Language Centres of the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia and the University of Parma, as a specific language certificate tailored to assess the needs of English language primary teachers and meant to evaluate the competence they are expected to master in order to act efficiently and appropriately in class. This certificate will, in due time, become the official qualification needed by any primary teacher to start teaching English in the local state schools.

1. The Context

In March 2005, the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia was asked by the Local Education Authorities to act as consultant in a project which was meant to compile a list of the language skills that had to be mastered by primary level English language teachers, with a view to the possibility of developing a language certificate which might be used to assess the kind of qualification for foreign language teaching actually needed by primary language teachers.

Members of the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia had taken part in a Socrates Lingua Action ‘A’ project titled ‘Autonomy in Primary Language Teacher Education: An Approach using Modern Technology’, involving experts in Austria, Germany, Italy, Scotland and Spain. The close cooperation between the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia and the University of Stirling had led to the development of the PLEASE (Primary Language teacher Education: Autonomy and Self-Assessment) website6, which had been conceived as a self-evaluation tool addressed to pre-service and in-service primary language teachers.

This website had been devised to offer primary language teachers the possibility to assess their competence by going through five different checklists, each containing a series of statements describing the required language behaviours – listening, spoken interaction, spoken production, reading and writing - for primary language teaching. These statements had been obtained by adapting the B1 and B level descriptors of the Common European Framework of Reference to those areas which had been considered particularly meaningful for English-language primary teachers (see contributions to Jiménez Raya, Faber, Geweh & Peck, 2001; Faber, Gewehr, Jiménez Raya & Peck, 1999; Gewehr, Catsimali, Faber, Jiménez Raya & Peck, 1998).

The expertise gathered with the PLEASE website was used to compile a list of the language skills to be mastered by primary language teachers and to devise a testing tool for the profile thus defined.

The principle underlying the whole project was the same used for the website: to draw on existing tools, but adapt them to the specific context, reflecting critically on the learning context to which they would be addressed. The basic principle was, thus, that of devising, in our own way, an “appropriate pedagogy”. An appropriate pedagogy will take into account major features of the learners’ cultural identity. The debate, which links more generally to the learner-centred nature of educational interaction, has often drawn attention to critical approaches, learner empowerment and multicultural perspectives in general education (Bruner, 1996) as well as to issues of multilingual language policy and transcultural learning of EIL (English as an International Language) in language teaching and learning (Allison & Lee, 1999; Brady & Shinohara, 000; Brady & Shinohara, 2003; Kramsch & Sullivan, 1996; McKay, 2003; Murray & Kouritzin, 1997). In our case, this meant considering both the local and the professional cultures of the learners, thus recognizing the need to adapt rather than adopt existing tools as well as to negotiate objectives and testing tools of a teacher training programme with the learners themselves.

2. The Rationale of The PLEASE Website

Prior to the development of the PLEASE website, it was decided to refer to the relevant literature in the field of LTE (language teacher education)7 and to the outcomes of research conducted within and across different European countries (Johnstone, 1999, p. vii). The survey of research had provided an account of the outcomes (in terms of pupils’ language attainment, their metalinguistic knowledge and their attitudes) by the end of the primary school stage and of the main factors considered to influence these outcomes. Moreover, it had offered a series of recommendations for decisionmakers (Blondin et al., 1998), observing primary language classrooms first hand and conducting surveys of teachers’ views.

The analysis had also highlighted the need for more attention to be paid to such areas as:

wider-ranging skills in language for classroom management; greater competence in the language needed for autonomous professional self-development;

language awareness, as a basis for both classroom management and self-development8.

The role of language awareness in language teacher education can hardly be overestimated.9 The range of activities covered includes, as pointed out by Trappes-Lomax ( 2002 ), awareness of teachers’ and students’ language use in the classroom; awareness of the discourse features of supportive, scaffolding teacher talk; classroom interaction; classroom discourse frames; awareness of different kinds of questions and their different pedagogical purposes; teachers’ awareness of themselves as language learners. Although the language profiles of the Common European Framework do not include such a component, it was felt to be necessary to have it here, where it could be shown to contribute both to the teacher’s selfimprovement as a learner and to a reflective attitude towards teaching.10

Banking on the assumption that the language teacher is a language learner as well as a facilitator of language learning, two contexts had been singled out within which teachers should develop their language proficiency. These were the classroom context (teacher as a facilitator) and the professional development context (teacher as a learner). Moreover, since it is often quite difficult to separate language and pedagogy, as underpinning both is language awareness, it was decided to consider its impact on the teachers’ teaching and learning of the language.

Taking advantage of the above considerations, the research group had decided to rewrite the synthetic descriptions of the language behaviours associated with the levels of the Common European Framework of Reference, adapting them to the abilities and activities actually displayed by primary language teachers.

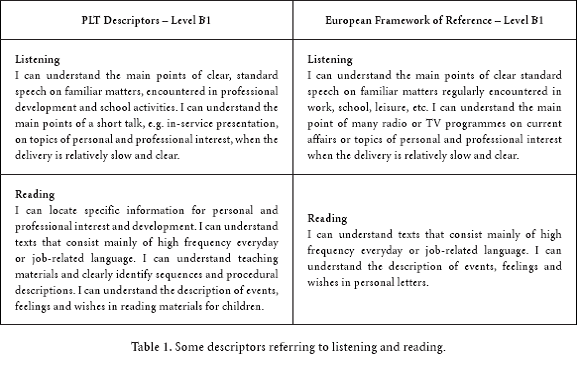

By comparing the document obtained for level B1 (see Appendix 1), with the contents of Common European Framework of Reference, it is immediately clear that, while the former actually contains indications for what concerns the overall language behaviour to be developed by primary language teachers, the latter refers to more general objectives. This can be observed by focusing, for instance, on the following statements referring to listening and reading:

The close analysis of the two sets of texts clearly shows how the former, by referring to ‘school activities’, ‘in-service presentations’, ‘teaching materials’ and ‘reading materials for children’, clearly identifies those contexts of language use which are particularly meaningful for primary language teachers.

Understandably, most of the descriptors are characterised by a certain vagueness. In the case of the CEF descriptors, this feature is mainly linked to the attempt to provide a flexible, central core, which will have to be integrated with the learning goals specific to particular contexts (North, 2000; Council of Europe, 2001; Alderson, 2002 ). On the other hand, the descriptors devised for testing the language competence of primary language teachers also retain some ‘general’ terms. This is mainly due to the fact that they are only intended as a reference point.

What we were trying to identify was the description of what we regarded as the ‘typical’ representative of effective practice, but the perspective adopted in defining its typicality has been that of ‘topologies’ rather than ‘typologies’. While the traditional typologies focus on delineating mutually exclusive categories and are set up as oppositions, which may, for example, classify learners as either elementary or intermediate, topologies are sets of criteria for establishing degrees of proximity among the members of some category, which is identified by a common core but fades off at the edges (Bondi, 1999a).

3. Primary Language Teaching Descriptors

After the above-mentioned general descriptions of language behaviours had been obtained, the need was felt, however, to develop more detailed checklists which would actually single out all the different abilities that primary language teachers should master.

These checklists were then devised, organised as a series of ‘I can’ statements and meant to reflect the teachers’ linguistic competences within the key contexts of classroom management and professional self-development.

While recognising that a general description of all learners might be limited to communicative abilities, it was felt that a specific language awareness component would be necessary for the teacher. Accordingly, this third priority for development was addressed, too, through a separate grid and checklist with ‘I know’ rather than ‘I can’ statements.

The PLEASE website had been devised to provide primary language teachers with a self-evaluation tool, which could help them to assess their competence in five different skills and three different contexts of use (classroom management, professional selfdevelopment and language awareness). On the basis of the official descriptors of level B1 and B , we selected the statements that were most relevant for the teachers and adapted them to the teaching context: 98 descriptors were thus developed with reference to the five different skills mentioned in the Common European Framework of Reference (for the full list of the descriptors of the PLEASE checklists, see Appendix 2).

4. Towards a Language Certificate for Primary Teachers

After completing the tentative list of the abilities to be mastered by primary language teachers, it was decided to employ them as the constituent parts of a language profile11, meant to provide a detailed analysis of the primary language teacher’s proficiency in relation to the typical uses of the FL needed.

The profile was validated in a series of meetings with primary teachers who would be involved in the training programmes leading to the certificate. The negotiation of the contents of the profile with the teachers allowed for a closer matching between the teaching programmes and the certificate to be produce.

Once the overall picture of a typical FL primary teacher was completed, it was decided to go on to consider how we could devise the draft of a language certificate for primary language teachers.

The CEPT (Certificate of English for Primary Teachers) undertakes the following:

to assess language skills at level B1;

to assess those skills which are directly relevant to the range of uses in which primary language teachers will be involved;

to cover the five language skills (listening, spoken interaction, spoken production, reading and writing) mentioned in the Common European Framework of Reference as well as knowledge of language structure and use in the contexts of classroom management and professional self development;

to provide accurate and consistent assessment of an additional skill, underpinning those normally employed by language teachers, namely language awareness;

to relate the various parts of the test to the professional role to be played by the candidates.

The various parts into which the CEPT is divided refer to the language domains12 which, after observing primary language classrooms and conducting surveys of teachers’ views, had been singled out as particularly meaningful for a primary language teacher; these are language for classroom management and language for professional self-development as well as language awareness.

Candidates who are successful in CEPT will be officially awarded the possibility of teaching English as a foreign language to primary school pupils by the local authorities.

The CEPT includes a reading paper, a writing paper, a listening paper and a speaking component13. The texts are authentic and adapted from real-world notices, articles, stories, texts from websites, reference books, and methodology books.

The Reading component contains four parts.

In part 1 of the test, the candidate will read five authentic notices and signs. For each one, the candidate must choose from three options the one that corresponds to the message in the notice or sign. For a sign saying “No access to District and Circle lines. Use exit at far end of platform”, for example, the three available options would be: a) Do not use this exit. b) This way out. c) Use this entrance.

In part of the test, the candidate is presented with a short story. Six sentences have been removed from the text. The candidate must read sentences A-G and decide where the sentences have to go in the text .There is one extra sentence.

In part 3, the candidate is presented with a longer factual text and needs to look for precise information. There are ten statements about the text following the same order of the text. The candidate should read these first and then scan the text to decide whether the statements are correct or incorrect.

In part 4, the candidate reads a short text containing factual interdisciplinary reference information with ten numbered spaces. There are three multiple choice options and the task is designed to test grammatical and lexical competence. The candidate must choose the appropriate word for each space.

The writing component contains three parts.

Part 1 focuses on grammatical precision and requires the candidate to correct five sentences that might be used in the classroom. In each sentence, there is ONE mistake. The candidate must find the mistake and rewrite the sentence correctly.

In part 2, the candidate is presented with some images and words in a box and asked to create a coherent short story using the given vocabulary.

In part 3, the candidate is given a letter to write following the guidelines indicated in the instructions. The letter is a longer piece of writing and focuses on the correct social forms and language used in letter writing.

The listening component includes three parts.

In part 1 of the test, the candidate listens to a recording taken from a short story. There are seven questions. For each question, the candidate will find three pictures. The candidate listens to the recording twice and chooses the right picture (A, B, or C).

In part , the candidate has to answer 8 multiple-choice questions as he or she listens to the text, choosing from three options.

In part 3 of the test, the candidate listens to a longer text, which will take the form of a lecturette in which teachers and/or teacher-trainers are talking about issues connected with the teaching/learning process. The candidate is presented with some notes summarising the content of the lecturette, from which seven pieces of information have been removed. As he or she listens, the candidate will fill in the numbered gaps on the page with words from the lecturette, providing the missing information.

The speaking component contains three parts.

The speaking part of the CEPT certificate is taken in pairs. The two candidates are assessed by two examiners. Only one of the examiners interacts directly with the candidates (posing questions, etc.), while the other acts as assessor and does not join in the conversation.

In part 1, the two candidates respond individually to one or two short questions posed by the examiner. One of the functions of this part is to allow the candidates to feel at ease, acquiring familiarity with the test setting.

In part , each candidate offers an extended “long-turn” around one of the following prompted tasks: story-telling and retelling; giving instructions; assigning and modelling a role-play, using a pair of written role-play cards; explaining learner errors.

In part 3, the two candidates interact with each other about aspects of their work and their workplace environment. A scripted question is posed first to one of the candidates who is asked to discuss the problem with the other candidate, and then to the second candidate who in turn discusses with the first.

The authors of the present study have been directly involved in the drafting of the third part of the listening component of the CEPT, namely, the lecturette. Therefore, a copy of this part is included in Appendix 3. The range of texts referred to in devising this part of the listening paper is characterised by a pedagogical focus as they may be extracts taken from in-service conferences, descriptions of short case-studies, or instructions on how to carry out activities in the classroom.

5. Conclusions

Quite often the complexity and fluidity of an L2 teacher’s interactional work is understated. In fact, the dual nature of language as a subject and vehicle places extreme demands on language teachers. Our attempt to devise a tool that might be used to assess the interactional skills and professionalism of language teachers cannot, therefore, be said to be definitive or comprehensive. Rogers (1969, p. 104) believed that “the only man who is educated is the man who has learned how to adapt and change; the man who has realised that no knowledge is secure, that only the process of seeking knowledge gives basis for security”.

Keeping these words firmly in mind, we have devised an instrument, the Certificate of English for Primary Teachers, which is flexible enough to meet the different needs of a wide range of language teachers operating in manifold contexts. Since we feel that it is not possible to separate language, pedagogy and language awareness when considering the role of the primary language teacher, we have tried to develop a certificate which highlights and supports these connections.

Obviously, further studies and tests will be needed to ascertain the validity of the CEPT as a certificate meant to assess the language competence that should be mastered by primary language teachers.

1 An idea of the changes brought about in the past ten years can be got by comparing the survey carried out by Blondin, Candelier, Edelenbos, Johnstone, Kubanek-German & Taeschner (1998) with the more recent Edelenbos, Johnstone. & Kubanek ( 2006). An overview of policies and approaches is also provided by Nikolov and Curtain ( 2000).

2 According to the report, in almost all countries pupils have to learn a foreign language from primary education onwards: in 00 , approximately 50% of all pupils were learning at least one foreign language. This figure has been increasing rapidly since the end of the 1990s, when educational reform took place in a number of countries, particularly in central and eastern Europe, Denmark, Spain, Italy and Iceland, cf. http://www.eurydice.org/portal/page/portal/Eurydice/showPresentation?pubid=049E

3 For a critical overview of training programmes in Italy, see Lopriore ( 2006).

4 The Common European Framework of Reference is available at: http://www.coe.int/T/DG4/Linguistic/Source/Framework_EN.pdf. It is a document which consists of a series of levels (A1, A , B1, B , C1, C ) across five language strands – listening, spoken interaction, spoken production, reading and writing. It has been designed with adult language learners/users, as well as self-assessment in mind. It has the benefit of not being specific to any country or context and offers a continuum for identifying language proficiency within a self-assessment grid.

5 For what concerns the legislative records in Italy, reference can be made to: Documento a cura del Comitato Tecnico Scientifico I.N.D.I.R.E., which states: “[…] se (il docente non è uno specialista, ha una competenza minima di livello B1 in una lingua straniera…” www.istruzioneer.it/allegato.asp?ID= 11 18. Information of a more general kind can also be found in Bondi, Ghelfi & Toni ( 2006).

6 For further information on the PLEASE website, see Poppi, Low and Bondi ( 2003); Poppi, Low and Bondi ( 2005).

7 See in particular approaches to reflective teaching and self-development (Li, Mahoney and Richards, 1994; Freeman and Richards, 1996). Attention was also paid to the perspectives of nonnative teachers. For an analysis of the issues see Llurda ( 2005).

8 For an overview of the complexity of the linguistic competence proposed for language teacher preparation, its components, the interaction among them and the implications for language teaching, see Celce-Murcia, Dörney & Thurrell (1995).

9 On the important role played by language awareness in LTE (language teacher education), see, for instance: Andrews & McNeill ( 2005); Bondi (1999a); Bondi (1999b); Murray ( 2002 ); Sharwood-Smith ( 2006); Wright ( 2002 ).

10 For a detailed analysis of ways available to teachers for exploring and reflecting upon their classroom experiences, see Richards and Lockhart (1994).

11 The profile is described in Bondi, Poppi ( 2006).

12 More information on the concept of ‘language domains’, defined as the context of situation in which language is used, can be found in Lee (2001), where it is defined in relation to other notions such as genre and text type.

13 The guidelines mentioned in the present study are the product of the joint efforts, collaboration and revisions of a team of experts including Glenn Alessi, Marina Bondi, Silvia Cacchiani, Claire Darby, Gillian Mansfield, Sian Morgan, Franca Poppi, Sara Radighieri, Marc Silver, Patricia Taylor and Claire Vickers.

References

Allison, D., & Lee, W. Y. (1999). Appropriate pedagogy? Evaluating a teaching intervention. Hong Kong Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(1), 61-77. [ Links ]

Alderson, J. C. (Ed.) ( 2002 ). Case studies in the use of the Common European Framework. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [ Links ]

Andrews, S., & McNeill, A. ( 2005). Knowledge about language and “good” language teachers. In N. Bartels (Ed.), Applied linguistics and language teacher education (pp. 159-178). New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Blondin, C., Candelier, M., Edelenbos, P., Johnstone, R., Kubanek-German, A., & Taeschner, T. (1998). Foreign languages in primary and pre-school education. A review of recent research within the European Union. London: CILT. [ Links ]

Bondi, M. (1999a). A language profile for the FL primary teacher. In M. Bondi, P. Faber, W. Gewehr, M.J. Jiménez Raya, L. Low, C. Mewald, & A. Peck (Eds.), Autonomy in primary language teacher education. An approach using modern technology (pp. 53-59). Stirling: Scottish CILT. [ Links ]

Bondi, M. (1999b). Language awareness and EFL teacher education. In W. Gewehr, M. Jimenez Raya, P. Faber, & A. Peck (Eds.), European Perspectives on Language Teacher Education (pp. 89-105). Berlin: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Bondi, M., Ghelfi, D., & Toni, B. (Eds.). ( 2006). Teaching English. Ricerca e pratiche innovative per la scuola primaria. Napoli: Tecnodid Editrice. [ Links ]

Bondi, M., & Poppi, F. ( 2006). L’insegnante di lingua straniera nella scuola primaria: per un profilo e per una certificazione delle competenze. In M. Bondi, D. Ghelfi, B. Toni (Eds.), Teaching English. Ricerca e pratiche innovative per la scuola primaria (pp. 13- 9). Napoli: Tecnodid Editrice. [ Links ]

Brady, A., & Shinohara, Y. ( 2003). English additional language and learning empowerment: Conceiving and practicing a transcultural pedagogy and learning. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 13, 75-93. [ Links ]

Brady, A., & Shinohara, Y. ( 2000). Principles and activities for a transcultural approach to additional language learning. System, 28(2 ), 305-322 . [ Links ]

Bruner, J. S. (1996). The culture of education. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Celce-Murcia, M, Dörney, Z., & Thurrell, S. (1995). Communicative competence: A pedagogically motivated model with content specifications. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 6(2 ), 5-35. [ Links ]

Council of Europe ( 2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Documento a cura del Comitato Tecnico Scientifico I.N.D.I.R.E.: Formazione di competenze linguistico-comunicative della lingua inglese dei docenti della scuola primaria. Retrieved May 31st, 2007 from http://www.istruzioneer.it/allegato.asp?ID=211218 [ Links ]

Edelenbos, P., Johnstone, R., & Kubanek, A. ( 2006). The main pedagogical principles underlying the teaching of languages to very young learners. Languages for the children of Europe: Published research, good practice and main principles. European Commission Report. EAC 89/04. [ Links ]

European profile for language teacher education – Final Report September 004. Retrieved May 31st, 007 from http://ec.europa.eu/education/ policies/lang/doc/profile_en.pdf [ Links ]

Faber, P., Gewehr, W., Jiménez Raya, M.J., & Peck, A (Eds.) (1999). English teacher education in Europe. New trends and developments. Munich: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Freeman, D., & Richards, J. C. (Eds.) (1996). Teacher learning in language teaching. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Gewehr, W., Catsimali, G., Faber, P., Jiménez Raya, M., & Peck, A.J. (Eds.) (1998). Aspects of modern language teaching in Europe. London and New York: Rutledge. [ Links ]

Jiménez Raya, M., Faber, P., Gewehr, W., & Peck, A.J. (Eds.) ( 2001). Effective foreign language teaching at the primary level. Munich: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Johnstone, R. (1999). Foreword. In M. Bondi, P. Faber, W. Gewehr, M.J. Jiménez Raya, L. Low, C. Mewald, & A. Peck. (Eds.), Autonomy in primary language teacher education. An approach using modern technology (p. viii). Stirling: Scottish CILT. [ Links ]

Key data on teaching languages at school in Europe - 2005 Edition Retrieved May 31st, 2007 from http://www.eurydice.org/portal/page/portal/Eurydice/showPresentation?pubid=049EN [ Links ]

Kramsch, C., & Sullivan, P. (1996). Appropriate pedagogy. ELT Journal, July, 50(3), 199- 212 . [ Links ]

Lee, D.Y.W. ( 2001). Genres, registers, text types, domains, and styles: Clarifying the concepts and navigating a path through the BNC jungle. Language, Learning & Technology, 5(3), 37-72 . [ Links ]

Li, D., Mahoney, D., & Richards, J. C. (Eds.) (1994). Exploring second language teacher development. Hong Kong: City Polytechnic of Hong Kong. [ Links ]

Lopriore, L. ( 2006). The long and winding road. A profile of Italian primary EFL teachers. In M. McCloskey, J. Orr, & M. Dolitsky. (Eds.), Teaching English as a Foreign Language in Primary School (pp. 59-82 ). TESOL Publications: Alexandria, Virginia. [ Links ]

Llurda, E. ( 2005). Non-native language teachers. Perceptions, challenges and contributions to the professions. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

McKay, S. L. ( 2003). Toward an appropriate EIL pedagogy: Re-examining common ELT assumptions. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(1), 1-22 . [ Links ]

Murray, G., & Kouritzin, S. (1997). Re-thinking second language instruction, autonomy and technology: A manifesto. System, 5(2 ), 185-196. [ Links ]

Murray, H. (2002 ). Tracing the development of language awareness: An exploratory study of language teachers in training. Bern: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft. [ Links ]

Nikolov, M., & Curtain, H (Eds.) 2000. An early start: Young learners and modern languages in Europe and beyond. Graz: European Center for Modern Languages. [ Links ]

North, B. ( 2000). The Development of a common framework scale of language proficiency. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

PLEASE website. Retrieved May 31st, 007 from http://www.please.unimore.it [ Links ]

Poppi, F., Low, L., & Bondi, M. ( 2003). Fostering autonomy: Implementing change in teachers’ education. In J. Gollin, G. Ferguson, & H. Trappes- Lomax (Eds.), Papers from three IALS Symposia – 2000, 2001 and 2002 (pp. 1-11). Edinburgh: IALS. [ Links ]

Poppi, F., Low, L., & Bondi, M. ( 2005). PLEASE (Primary Language teacher Education: Autonomy and Self-Evaluation). In B. Holmberg, M. Shelley, & C. White (Eds.), Distance education and languages. Evolution and change (pp. 95- 308). Clevedon, Buffalo, Toronto: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Richards, J.C., & Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Rogers, C.R. (1969). Freedom to learn. Columbus, Ohio: Charles E. Merrill. [ Links ]

Seidlhofer, B. (1999). Double standards: Teacher education in the expanding circle. World Englishes, 18(2), 233- 245. [ Links ]

Sharwood-Smith, M. ( 2006). The evolution of teachers’ language awareness. Language Awareness. 5(1), 1-19. [ Links ]

The Common European Framework of Reference. Retrieved on May 31st, 007, from http://www.coe.int/T/DG4/Linguistic/Source/Framework_EN.pdf [ Links ]

Trappes-Lomax, H. ( 2002 ). Introduction. In H. Trappes-Lomax, & G. Ferguson (Eds.), Language in language teacher education (pp. 1- 21). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Wright, T. ( 2002 ). Doing language awareness. Issues for language study in language teacher education. In H. Trappes-Lomax, & G. Ferguson (Eds.), Language in language teacher education (pp. 113- 130). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [ Links ]