Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Print version ISSN 1657-0790On-line version ISSN 2256-5760

profile no.9 Bogotá Jan./June 2008

The English Language Learning inside the Escuela Activa Urbana Model in a Public School: A Study of Sixth Graders

El aprendizaje del inglés en el marco del modelo Escuela Activa Urbana en un colegio público: un estudio en grado sexto

Odilia Ramírez Contreras*

Liceo Cultural Eugenio Pacelli & Universidad de Caldas, Colombia,E-mail: odiliarc@yahoo.com Address: Calle 66C No. 41B-21 Barrio Las Colinas, Manizales, Colombia.

This study reports the findings of research dealing with sixth-graders’ perceptions of English language learning and the impact of active learning approaches in a public school in Manizales, Colombia. Participants in the research were involved in lessons planned according to the principles of task-based learning and active learning, inside the Escuela Activa Urbana model implemented by some private and public institutions in this city. The findings reported a positive impact of the model on the language learning process which was reflected in the increase of students’ participation, language production, and class interaction.

Key words: English as a foreign language, task-based learning, active learning, teamwork

Este estudio reporta los hallazgos de una investigación sobre las percepciones del aprendizaje de la lengua inglesa por parte de alumnos de sexto grado y el impacto de enfoques de aprendizaje activo en un colegio público en Manizales, Colombia. Los participantes en la investigación tomaron parte en clases planeadas de acuerdo con los principios del aprendizaje basado en tareas y de las metodologías activas en el marco del modelo Escuela Activa Urbana implementado por algunas instituciones públicas y privadas de la ciudad. Los hallazgos reportan un impacto positivo del modelo en el proceso de aprendizaje de la lengua el cual se refleja en el incremento de la participación, la producción lingüística y la interacción de los estudiantes.

Palabras clave: Inglés como lengua extranjera, aprendizaje basado en tareas, aprendizaje activo, trabajo en equipo

Introduction

Teachers in public schools in Colombia are permanently challenged by young learners’ attitudes towards English: lack of motivation or discouragement due to the belief that English pronunciation and grammar are unbearable are two of the comments teachers frequently make about their daily teaching. In fact, it is this challenge that makes teachers work hard on the planning of lessons that really attract the students’ attention and that help them feel that learning English is not so unendurable. This is something most teachers try to do with the implementation of the communicative approach (McDonough & Shaw, 2003) and the learner-centered curriculum (Nunan, 1994), as in the public school where this research project was conducted and in which active methodologies are being applied as part of the new pedagogical model it recently adopted for the middle and high school levels.

Theoretical Framework

The theory supporting this research project includes aspects related to teaching methodology and language learning; the former refers not only to teaching English as a foreign language (EFL), but to the process of teaching as a school approach, common to all subjects; the latter directs the attention to the specific process of learning a foreign language, in this case the learning of English in a public school that follows the Urban Active Learning School model (Escuela Activa Urbana).

A current trend in public schools in Manizales is the implementation of the Active Learning Approach that refers to the level of engagement by the student in the learning process (Fern, Anstrom, & Silcox, 1994). Based on the principles stated by different pedagogues throughout history, this model was given the name Escuela Activa Urbana (Urban Active Learning School) as an educational project locally promoted by Fundación Luker1 and Secretaría de Educación de Manizales2. According to Gallego & Ospina (2002), the active learning approach this project is based on cites different educators in history and claims the following:

Education must be individual, spontaneous and natural, as stated by Rousseau in the 18th century. In the same vein, nature is a learning resource for the students.

Observation and manipulation of words and objects lead the kids to learning, (Comenius, 1670, as cited in Gallego & Ospina, 2002).

Education means the building of the kid’s personality within natural and spontaneous environments, as Pestalozzi (1820) claimed in the 19th century.

Pragmatic learning based on permanent activity and stimulation, as Dewey (1950) concluded, facilitates progress.

Group work with assigned roles, as stated by Montessori (1950), facilitates learning.

Learning and instruction are more effective when situated within the students’ context and view of the world around them, as stated by Freire (1965) in his philosophy of education.

Learning is better achieved when new information is just beyond the students’ previous knowledge, as proposed by Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development theory.

Teachers are guides or facilitators of learning.

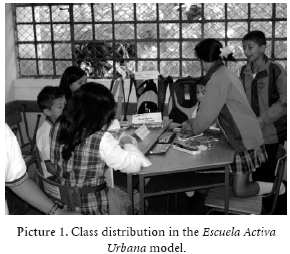

Since one of the most important features in the active learning methodology is group work, the physical environment of the classroom with this methodology is completely different from the traditional rows in which the students faced the board and the teacher. According to Gallego & Ospina (2002), furniture is now arranged so that students can move from learning centers or group discussion to plenaries in which they socialize knowledge and experiences. According to Fundación Luker (2007), the use of hexagonal moveable tables helps class distribution. Thus, roles are assigned within each group such as moderator, time controller, spokesperson, essayist, logistics chief, and note-taker.

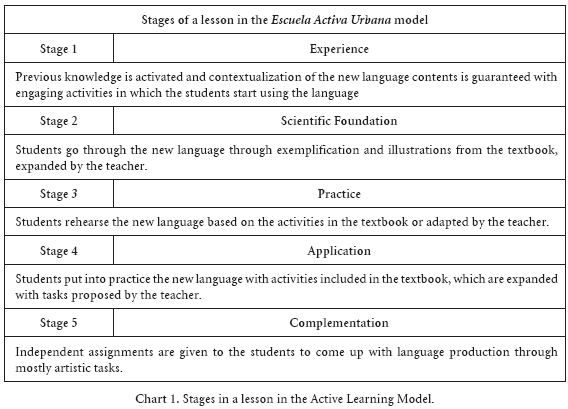

Besides class distribution, lesson planning also reflects some changes within the Escuela Activa Urbana model (Gallego & Ospina, 2002). Chart 1 shows the five stages identified in a lesson:

Concerning the learning of English as a foreign language, this project focuses on the theory about task-based learning (TBL). Willis (1996), cited by McDonough & Shaw (2003), stated that “tasks are always activities where the target language is used by the learner for a communicative purpose… in order to achieve an outcome” (p. 48). As can be seen, there is a strong stress on a product, on the achievement of a goal. Due to its emphasis on communication, TBL deals with accuracy and fluency and comprises the following three phases (ibid):

1. Pre-task phase: the learner is introduced to the new topic and given new language.

2. The task cycle itself: the learners do the task and plan how to tell or show the class their production; finally they report what they did.

3. Language focus: learners analyze and practice the language learned.

Context

The school where this study was conducted is a public school in Manizales which serves a low socioeconomic stratum community in the south of the city. The school works under the guidelines of a cultural and environmental-oriented pedagogical project from pre-school to eleventh grade; it has about 850 students, 320 of which belong to middle and high school. The study was conducted with three 37-student sixth grade groups (46 girls and 65 boys, average age 13 years old) to whom I taught English as a foreign language three classes a week. For the school year 2007, the school adopted the Escuela Activa Urbana methodology in the middle and high school levels, which implied a series of changes in the classroom including class distribution, self-instruction principles, textbooks, teamwork, and leadership, among others.

The English as a foreign language syllabus is based on language functions which derive from the standards stated by the National Ministry of Education (2006). For seven years the school has offered middle and high school education and the English classes have been taught mainly within traditional grammar-oriented practices. Sixth graders’ background in English at the beginning of the school year was restricted to vocabulary about animals, family members and colors.

As a teacher researcher, my main concern dealt with the impact of the methodology adopted by the school for the EFL class, since both the students and I were not very familiar with this model’s procedures. I started to reflect on my own teaching style, which I have always tried to make fit the principles of the communicative approach, and on what is expected from a teacher inside the Escuela Activa Urbana methodology. I found several similarities and realized that my main role was supposed to be that of a facilitator, a guide, an observer, at times a judge, but one always open to the students’ learning needs. Considering this, I decided on a task-based approach to my classes which helped me meet the expectations and needs of both the institution and the students. In the same way, as a permanent participant observer of the teaching-learning process, I decided on a qualitative descriptive approach to research, taking advantage of the various possibilities for data collection later on described.

Research Questions

With the purpose of reflecting on the changes the school was going through, the following research questions were asked:

- How do sixth grade students perceive the learning of English as a foreign language (EFL)?

- What is the impact of Escuela Activa Urbana methodology on sixth graders’ English language learning process?

Methodology

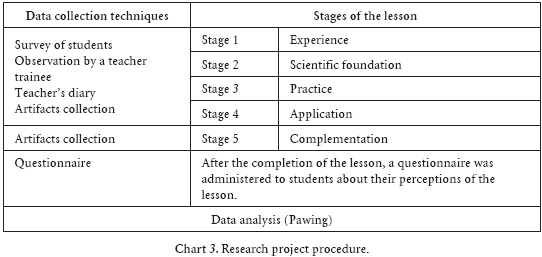

This research project corresponds to the qualitative descriptive research since, as Seliger & Shohamy (2003) claim, it attempts “to present the data from the perspective of the subjects or observed groups” and it “involves a collection of techniques used to specify, delineate, or describe naturally occurring phenomena without experimental manipulation” (p. 124). The project was carried out during the second and third academic terms of the 2007 school year; the research started at the end of the first term of the school year with a survey (Appendix 1) in which the students were asked about the kind of attitudes and emotions that the English class elicited from them and the level of difficulty of each one of the language skills (listening, speaking, reading and writing). In the second and third terms, various classes were observed by a teacher trainee from a local state university whose observations were recorded in a journal. As a teacher researcher –participant observer– I completed my own journal in which I recorded my personal views of each observed and taught lesson. I tried to focus on the students’ attitudes, perceptions, or reactions to the new methodology I was implementing in my classes, keeping in mind my role as a guide and facilitator of the learning process in response to the pedagogical principles of the model and to the principles of the chosen research methodology. At the end of each lesson, a questionnaire was administered to the students (Appendix 2) in which their perceptions about the learning process were recorded according to the tasks conducted. The students’ language production was analyzed through the collection of artifacts from classwork or extra assignments.

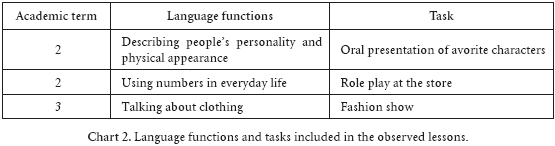

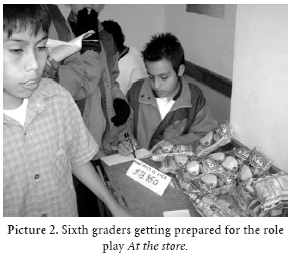

Three lessons were observed: the first one dealt with the use of language functions for descriptions of personality and physical appearance; the second one referred to the use of numbers for various purposes (time, math operations, quantities, and prices); and the third one dealt with clothing. Every lesson ended with a task in which the students were expected to use the language functions studied. Chart 2 presents the tasks corresponding to each lesson:

The analysis of the information collected was conducted through the domain analysis technique proposed by Ryan & Bernard (2002); pieces of information were ferreted out, using colors to identify the different categories arising from the analysis. As already stated, data analysis aimed at the identification of the students’ perceptions about the English learning process and the impact of Escuela Activa Urbana methodology on the students’ EFL learning process.

Procedure

According to Escuela Activa Urbana, the process of the observed lessons followed the stages shown in Chart 1; data were collected during the different stages of the lessons and artifacts collected from both in-class and extra-class assignments. Chart 3 summarizes the procedure followed:

Findings

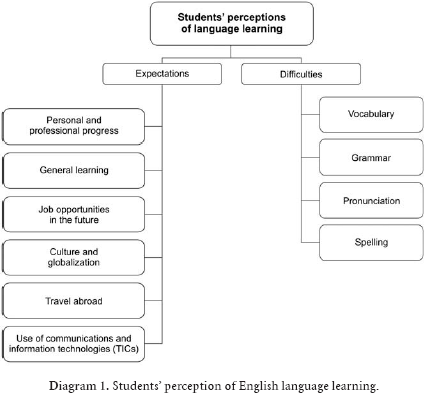

To answer the research questions stated, the findings were divided in two main sections: the students’ perceptions about the English class and the impact of the Escuela Activa Urbana methodology on the learning process. According to the analysis of the students’ survey, the questionnaires, the journals, and the artifacts, the students’ perceptions of the English language learning process were classified into two main categories: expectations and difficulties, as shown in Diagram 1 below:

Sixth grade students expressed a strong belief that English is important and that it can help them meet their own expectations of personal and professional progress, learning of other subjects, provide job opportunities, access to world culture, travel, and facilitate the use of TICs, mainly chatting on the internet. Some of their comments in the initial survey stated that: It is a way to get new jobs.3

To be able to travel abroad.

It makes me feel like learning in order to succeed in the future.

It helps me be a more efficient person.

I can succeed and get new job opportunities.

I get interested in other cultures.

I might be able to chat on the internet.

These comments provided evidence of what was stated by Freire (as cited in Fundación Luker, 2007) when referring to taking into account students’ views of the world in the classroom, since it is they who determine the areas of interest in the learning process; these views also reflect the desire to achieve high levels of personal and professional growth, which is one of the main purposes of active learning approaches.

When talking about the difficulties they encountered in the learning of English as a foreign language, the students mentioned four specific factors affecting their learning process: differences in pronunciation and spelling on the one hand, and a lack of vocabulary and knowledge of grammar, on the other. It seemed to be really hard for them to figure out complete sentences according to the English language grammatical and phonetic systems. The first two aspects referred to the differences between the pronounced and the written forms of words in English. The observed lessons reported a permanent struggle on the part of the students to overcome the difficulties that the differences between the English and the Spanish languages represented. These differences were insistently argued as the main reasons for their lack of understanding, their confusion, and sometimes desperation. They can be illustrated with some comments from the survey and the questionnaires, to wit:

Words are written a different way than they are pronounced.

One gets confused when pronouncing words because they are written in a different way.

It’s difficult to remember the spelling since words are written and pronounced in a different way.

Words are written one way and pronounced a different one.

The same concern was referred to in my journal where I wrote the following:

Most students’ confusion stems from the difference between written and pronounced forms.

Lots of questions about pronunciation and spelling were asked.

The other two aspects mentioned by the students when referring to difficulties in the learning process dealt with vocabulary and grammar. Most of them had trouble when expressing ideas due to their lack of vocabulary. That is why most of the time they asked for translation by the teacher or looked up in the dictionary the words they needed to complete the tasks assigned. They also referred to the fact that word order is different in English and Spanish which makes English learning confusing, boring, and excessively challenging. The following are some excerpts from the survey and questionnaires:

Many times words go backwards in comparison to Spanish word order.

You must know a lot of verbs and prepositions.

It’s difficult because you have to put words in an order opposite to Spanish word order.

I know very little vocabulary and not knowing much grammar makes English nonsense to me.

English is like a labyrinth.

The teacher trainee and I reported similar comments in our journals:

The students always wanted to translate word by word.

They wanted the teacher to give all the vocabulary they needed.

Vocabulary seemed to be the most relevant difficulty among the students.

These subcategories dealing with difficulties in the learning process reflected the language learning background of the students. They proved to be excessively dependent on translation and grammar; their main concern seemed to be the achievement of accurate language in terms of grammar, pronunciation, spelling, and vocabulary; the last one guaranteed by translation, ignoring communication in real life situations. In spite of the students’ constant complaints about the abovementioned difficulties and differences, they got to interact with their peers and help each other in the achievement of each language lesson, as expected inside the Escuela Activa Urbana model and as proposed by Comenius (1670), Montessori (1950), and Vigotstky (1917) (as cited in Gallego & Ospina, 2002).

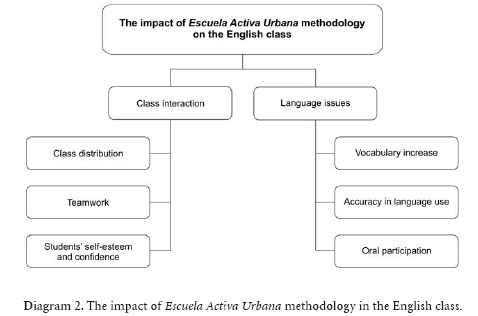

The Impact of Escuela Activa Urbana Methodology

The categories that had to do with the impact of the Escuela Activa Urbana methodology included the following two main aspects: class interaction and language issues, as shown in Diagram 2.

According to Diagram 2, one of the main concerns on the part of both the students and the teacher was the class distribution which was referred to as the most remarkable change in the class scheme. According to the teacher’s and the students’ comments, the group distribution in hexagonal tables promoted conversation, distraction, and a lack of concentration on the tasks, mainly because most of the students lacked the necessary basic listening skills to follow instructions; in fact, the students complained that the class did not listen to them when speaking English, that the class was too noisy, or that they did not concentrate on the language which was used in class. The following are some comments taken from the questionnaires:

The members of the group speak too much and they do not pay attention.

The class lacks listening skills.

It’s difficult because sometimes everybody talks and it is impossible to hear.

It is difficult to get concentrated when somebody else talks to you.

The noise does not let you concentrate.

The same comments were made by the observer and me; we wrote the following in our journals:

It was necessary to stop the exercise for requesting the student’s attention.

Most of the students were talking about personal issues.

Very few students followed the instructions at the beginning.

The groups talked among them while the teacher tried to give instructions.

At some point, I was concerned about the noise the neighbor teachers might have heard.

According to the people involved in the class (students and teacher), this new distribution demanded more time and effort for the achievement of the objectives of the lesson, but at the same time fostered interaction because students were more willing to help and support each other or ask the teacher questions when conducting the tasks; some comments in the questionnaires stated:

I liked the fact that I had more classmates around to whom to ask about the class stuff.

We helped each other and if I didn’t know, the good-at-English students would give me the vocabulary.

Things are easier when you can ask questions about vocabulary and pronunciation.

The teacher and the classmates clarified the translation to me.

This fact was also noticed by the observer who wrote in her journal:

Some usually quiet students dared to ask questions about vocabulary.

Students shared ideas about the answers and possible designs.

Posters helped students interact when designing them.

Another important finding reveals the increase of teamwork skills among the students; in spite of the difficulties related to time and student talking, the roles established in the groups according to the Escuela Activa Urbana methodology helped students recognize and respect responsibilities and rights among themselves:

It is good to have responsibilities; this way you are not bulled.

When we help each other we are more productive.

Sometimes I understand better with the help of my classmates.

In small groups I am not afraid of speaking up and I give opinions.

I was ashamed to stay quiet so I had to speak up.

The group almost forced me to participate.

I had to collaborate.

Once again, class interaction arose as an important improvement in the language class since the students became aware of the importance of their roles within a group and of their previous knowledge, as respectively stated by Montessori and Vigotsky when cited by Gallego & Ospina (2002); students also realized the significance of their own achievements in relation to both their linguistic performance (Willis, 1996), and of their personal growth (Fern, Anstrom, & Silcox, 1994). The active learning approach to my lessons proved to be beneficial because it fitted the stages of the new model (Gallego & Ospina, 2002), which helped the students go up the ladder in a sequential way.

One of the most satisfying aspects reported with the use of the Escuela Activa Urbana methodology in the English class was the raising of students’ selfesteem and confidence when conducting or participating in the tasks; some students commented as follows in the questionnaires:

I had never participated in class and this time I dared to do it because I knew what I was going to say.

Nervous but I was able to speak in public; it felt good.

When you show what you do you feel confident to speak in English.

The journals reported this aspect, too:

When students showed their production (posters) they felt confident…Girls who never spoke were able to participate in the fashion show and speak in public…Although they looked a little nervous the students were strong enough to speak aloud.

Concerning language, I could see that the students showed significant progress in their English language use; one important finding deals with vocabulary increase as a result of class interaction and task-based learning; in general, students liked the kind of activities conducted in the observed lessons and they enjoyed expressing their own likes, views, and creativity; that is, working with meaningful tasks that made them use the language for real communication.

Some of the comments the students made in the questionnaires after they performed the tasks acknowledged are as follows:

I like to do real life things.

It is easy to fix ideas according to what you do.

I liked writing about my favorite singer; it was easy.

It’s like playing; we were playing the store in English.

Although I was nervous, I liked going on the runway and describing myself in English.

I was not afraid of expressing myself as a model.

I didn’t like the fact that some students had fun on me. However, I could participate in the fashion show and speak in public.

As an additional gain, accuracy was also reported as a significant improvement on the part of the students since they used the functions dealt with for the particular purposes of each lesson with accurate language. This finding was reported in the questionnaires where the students wrote the following:

It was easy to write the sentences with the examples the teacher provided us with.

With the pictures and the vocabulary we can come up with ideas in a better way.

The journals reported similar facts:

In general, the language production was good, fewer mistakes were found…Simple and at the same time correct sentences were used to present the posters…The students introduced themselves with correct sentences…Vocabulary about clothes was easily used in the fashion show.

Concerning language use, probably the most outstanding improvement in the class was oral and volunteer participation; in spite of the messy and noisy atmosphere described in the data collection instruments, most of the instances corresponded to the willingness of volunteers to socialize their language production; the students referred to this in the questionnaires:

Sometimes you cannot hear because everyone wants to respond.

Many times you are not allowed to speak.

Since I had the sentences, I could participate several times.

The journals showed the same facts concerning class participation:

The class had to be stopped to assign more orderly turns among students.

Some students ran to the front of the class to give their examples.

Some kids yelled their answers without following instructions.

It is important to highlight the direct relationship between the subcategories belonging to class interaction, mainly the one related to the students’ self-esteem and confidence, and the subcategories dealing with language issues. Definitely, the more secure the students are the better their language production is. As the research progressed, I could observe that my students became more self-confident, which led them to higher levels of language production and, subsequently, to higher levels of participation.

Conclusions

Although changes in the Colombian Educational System have become quite frequent in the last decades (Valencia, 2005), teachers must be prepared to adapt their teaching practices to the new trends and guidelines adopted by their schools; every change is a challenge, and as such, teachers need to keep in mind that the core of the educational artistry remains: our students, those challenging subjects who permanently demand variety, flexibility and motivation. The mixture of an active learning approach and a task-based orientation proved to help EFL teaching professionals cope with the many difficulties that traditionally placed the English class in the list of boring or stressful subjects in the curriculum.

Teamwork, as one of the main goals of the Escuela Activa Urbana model, must be the result of effective communication among peers in the classroom who work together for the achievement of objectives and the completion of tasks that reflect appropriate, sequential, and contextualized lesson planning. Teamwork skills must become part of the curriculum goals so that the future generations can actively participate in their own learning in class environments in which speaking up as regards their own ideas, opinions, and experiences can be done in the foreign language through the implementation of task-based activities.

The learning of basic listening skills in the classroom and inside the groups in the Escuela Activa Urbana methodology takes time, especially for young EFL learners; active learning approaches completely change the class atmosphere since students are permanently interacting and participating as agents in their own learning process. Teachers and administrators must be aware of their new role as facilitators and of the need for a clear understanding of what really happens in the classroom: active learning. This way, frequent noisy or messy class activities will not be judged as lacking classroom management or discipline.

EFL theory can be easily incorporated into wider teaching models like the Escuela Activa Urbana in Manizales. In this particular case, task-based learning in the English class was effectively taken advantage of for the accomplishment of school goals aimed at the education of young learners through teamwork, contextualization, participation, and so on. This is a key point teachers can take into consideration when making decisions about their teaching. Schools working under the same guidelines (Escuela Activa Urbana) are recommended to take advantage of the adaptability of taskbased learning into the stages of this model so that the principles of the learner-centered curriculum and the communicative approach can be put into practice and fostered permanently.

Meaningful and active classes help teachers change the students’ negative perceptions of English as a foreign language. When students feel that they can use the language for real communication of their own experiences or views of the world, their self-esteem and confidence grow and the process of the class flows more efficiently, making learning happen. This is the most important reflection from this piece of research.

1 Fundación Luker (Luker Foundation) is a private institution belonging to the production sector of the national economy.

2Secretaría de Educación de Manizales is the Board of Education belonging to the municipality administration.

3 To ensure understanding, the survey and questionnaires for students were administered in Spanish.

References

Brown, D. (1994). Principles of language learning and teaching. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall Regents. [ Links ]

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. London: Cambridge. [ Links ]

Fern, V., Anstrom, K., & Silcox, B. (1994). Active learning and the limited English proficient student. Directions in Language and Education National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education, 1 (2). Retrieved November 10, 2007, from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/pubs/directions/02.htm [ Links ]

Fundación Luker. (2007). Memorias Segundo Seminario de Escuela Activa Urbana. Manizales: Fundación Luker. [ Links ]

Gallego, L., & Ospina, J. (2002). Escuela Nueva. Dimensionada en la educación básica. Manizales: Litógrafos Asociados. [ Links ]

McDonough, J., & Shaw, C. (2003). Materials and methods in ELT: A teacher’s guide. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional (2005). Bases para una Nación Bilingüe y Competitiva. Al Tablero, 37, Bogotá D.C.: MEN. [ Links ]

_______(2006). Formar en lenguas extranjeras: ¡El reto! Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: inglés. Serie Guías No. 22. Bogotá D.C.: Imprenta Nacional. [ Links ]

Nunan, D. (1994). The learner-centered curriculum. N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ryan, G., & Bernard, H. R. (2000). Techniques to identify themes in qualitative data. Retrieved June, 2006 from http://www.analytictech.com/mb870/Readings/ryan-bernard_techniques_to_identify_themes_in.htm [ Links ]

Seliger, H.W., & Shohamy, E. (2003). Second language research methods. Oxford: Oxford Univerity Press. [ Links ]

Valencia, S. (2005). El bilingüismo y los cambios en políticas y prácticas en la educación pública en Colombia: Un estudio de caso. Retrieved April 4, 2007 from http://www.bilinglatam.com/espanol/informacion/Silvia%20Valencia%20Giraldo.pdf [ Links ]

Willis, J. (1996). A Framework for task-based learning. Harlow, Essex: Longman. [ Links ]