Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile no.10 Bogotá July/Dec. 2008

Teacher Collaboration in a Public School to Set up Language Resource Centers: Portraying Advantages, Benefits, and Challenges*

Trabajo cooperativo de profesores de un colegio público para crear centros de recursos de lenguas: retrato de sus ventajas, beneficios y desafíos

Javier Augusto Rojas Serrano**

Universidad Nacional de Colombia

** E-mail: javirse@yahoo.com.mx

Address: Diagonal 146 No. 136A 59 Int. 7 Apto 528, Suba.

This article was received on March 25, 2008 and accepted on July 23, 2008.

In the present article, the author attempts to describe the benefits, challenges, advantages and disadvantages experienced by teachers in a public school when working collaboratively to implement a language resource center in their institution. Taking as a point of departure the development of a proposal to implement the resource center in their school, some teachers engaged in group work in order to attain the different objectives that were stated at the beginning of the process, thus encountering a number of difficulties and challenges. When overcome, these difficulties and challenges rendered good opportunities for teachers to develop further in their professional and personal life as well as to improve the school environment and classroom practice.

Key words: Collaborative work, language resource center, teacher professional development

En el presente artículo, el autor se propone describir los beneficios, desafíos, ventajas y desventajas que un grupo de profesores de un colegio público encontraron al trabajar colaborativamente para implementar un centro de recursos de idiomas. Tomando como punto de partida la construcción de su propuesta de implementación del centro de recursos para la institución, algunos profesores decidieron trabajar en grupo para alcanzar los objetivos planteados al comienzo del proceso, encontrando una serie de dificultades y desafíos. Al superar dichas dificultades y desafíos, los docentes hallaron oportunidades para su desarrollo profesional y personal así como para el mejoramiento del ambiente escolar y del ejercicio docente.

Palabras clave: Trabajo colaborativo, centro de recursos de lenguas, desarrollo profesional docente

Introduction

The teaching profession has always been regarded as an important milestone in modern society. Francisco Imbernón (1997), in the introduction to "La Formación y el desarrollo profesional del profesorado" (Teachers' Professional Training and Development) highlights the increasing interest in Teacher Development, which is reflected in several forms, such as publications, lectures, reports and academic studies in general. This fact may be due to the recognition of teachers as powerful social elements, whose commitment influences social change and development, work relations, values and citizenship, as well as historical and cultural identity.

Because of the multifunctional presence of teachers in society, the studies devoted to their actions, activities and practices focus on many specific and individual aspects regarding the profession, viewed by scholars from varied academic fields.

Although in Colombia there is an increasing interest in teacher development issues in the area of languages, there is still a lack of studies related to practical and actual examples of actions undertaken by teacher development movements in the Colombian educational panorama, though this does not mean that these are non-existent (González, 2003, p. 88). Given this context, the present paper describes one of those ongoing joint efforts of school teachers aiming to reach a common goal in their institution, highlighting, in particular, the advantages, disadvantages, benefits and challenges made evident in this type of interaction. Undoubtedly, these attempts and activities are to be recorded, studied and analyzed because they will contribute to a large extent to the understanding of the Colombian teaching context, with its particular characteristics, needs and requirements, as well as of the teachers who are key elements in this dynamic.

As an assistant to a teacher updating program on the use of resource centers for language learning, I had the opportunity to work closely with teachers belonging to 5 public schools in the process of building proposals with the ultimate goal of setting up these centers in their institutions. This program, carried out in 2005 by the PROFILE Research Group of the Foreign Languages Department of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogotá and sponsored by the Secretary of Education of the city, focused on three major components; namely, language development, ELT methodology and use of the resource centers. Grupo de Investigación PROFILE & Programa ALEX (2004) offer a very comprehensive perspective of this program in the project presented to the Secretary of Education of Bogotá.

The writing and implementation of proposals for these resource centers entailed the exploration and analysis of current English curriculum and syllabi, review of methodologies and pedagogical approaches, assessment and evaluation of students' real levels of proficiency, and acknowledgment of resource center philosophies, among many other tasks. Hence, undertaking group work and collaborative efforts was decisive and, furthermore, absolutely necessary among teachers belonging to the same institution. As a witness of the processes and outcomes of teachers' cooperation and common pursuance of determined goals, I became greatly interested in their perceptions and challenges while engaging in collaborative endeavors during the program.

The question leading the present study was: What does the process of group work undertaken in Bogotá by teachers from a public school -in order to set up a resource center- tell us about teacher development activities and their characteristics within the Colombian context?

Taking this question as a point of departure, the following other queries also arose: Which are the most salient patterns of group work that emerge from such a process? How are those patterns of group work reflected in the proposal to set up the resource center? What are the feelings and perceptions of teachers with regard to teacher development activities and programs?

In order to address these questions as accurately as possible, I will first offer a brief yet comprehensive description of the context in which this study was produced, followed by the theories and previous works related to the research questions. Afterwards, I will explain the reasons for choosing a qualitative approach (case study) that helped me construct the subsequently delineated methodological framework.

The research findings and their ensuing pedagogical implications and limitations will follow. Finally, I will propose some paths for further research and draw some conclusions out from the study.

Context and Research Focus

This study was carried out among teachers belonging to one of five public education institutions involved in the teacher updating development program1 called 'Programa de Actualización para el Uso Pedagógico de los Centros de Recursos de Idiomas en la Localidad Cuarta de San Cristóbal'. This particular school was chosen because it had the most difficult geographical conditions as regards undertaking group work as well as the largest group of teachers taking part in the program among all the participating schools.

This public school belongs to the Localidad de San Cristobal, in the southeast of Bogotá, and has three campuses in different sectors of the zone, corresponding to the School headquarters or Sede A, and Sedes B and C. According to the information provided by the participating teachers throughout the process, this school serves a community from the lowest social strata, whose members are usually employees such as housekeepers, bricklayers, concierges, shop assistants, among others. Most of them do not have steady jobs, are underpaid or unemployed. Their levels of education generally do not allow them to help their children with academic assignments or to reinforce what children learn at school. The school population is about 3,000 students. In general, the most frequent problems found in the school have to do with violence, gangs, adolescent pregnancy, drugs, family violence, parental divorce, among others. This may produce, sooner or later, low academic performance or even separation from all school contact.

The academic activities in the school are based on its PEI (School Education Project), which emphasizes science and technology. That is to say, the basis of this educational project is founded on subjects such as mathematics, biology, physics, and similar sciences. The area of languages (including the study of Spanish, the mother tongue) has just an instrumental aim, as stated by the teachers themselves; this area is thought to serve in the achievement of high levels in the presentation and exposition of the "main subjects".

Even though the main purpose of the updating program was to help teachers come up with a proposal to implement a resource center for languages in their institution, these teachers were not all teachers of languages. From a group of 35 teachers, only 3 were actually teachers of English; the others were primary all-round subject teachers who taught children of ages ranging from 5 to 10. These teachers were also interested in learning English or improving their proficiency, and regarded the program and the resource center as tools that they could also take advantage of. These 35 teachers, who represented one of the five participating schools, were part of the 125 teachers that partook of the whole program.

All teachers were aware that the main purpose of their work was the setting up of the resource center to support the teaching of English at their schools.

Literature Review

Based on the analysis of the objectives of this study, three main areas emerged as target constructs of research: Teacher training and development, collaborative work among teachers, and the resource center philosophies and principles. These areas make up the spine of this research and lead the basic structure for subsequent analysis.

Teacher Training and Development According to Molina (2000), "Teacher training refers to preparation and professional development of teachers", and he describes pre-service instruction as the best example of teacher training. It has to do with "basic teaching skills, techniques, and activities, and the teaching and exploration of the four language skills" (Molina, 2000, p. 84).

Teacher development, on the other hand, refers to in-service programs which are directed to ongoing professional development and involves further reflexive and analytic skills. It means that the professional teacher needs to develop theories, awareness of options and decision-making abilities (Richards & Nunan, 1990).

From my viewpoint, the factor that really makes the difference between teacher training and teacher development is, precisely, reflection. This perception is not far from Molina's ideas, in the sense that in pre-service instruction students cannot reflect upon a professional practice that they are not undergoing yet; so, they can just receive instruction in language use, methodologies and pedagogical skills from a theoretical perspective (even though many language teaching programs in Colombia may offer teaching practice and microteaching, but not in a sustainable way).

Teacher development, on the other hand, is directed to in-service teachers whose real practice allows them to implement direct changes into their pedagogical activity. The PROFILE Research Group has contributed to this study by doing research and publishing papers in the area of teacher development in Colombia. This group has continuously offered valuable information on this matter since 1995, when it started to run teacher development programs in the public as well as private sector. The number of action research projects in these programs is outstanding. The program leads teachers that participate in the programs to carry out an action research project in order to tackle classroom problems. This means that a program for 120 teachers may yield 30 to 40 projects depending on the number of teachers in each group.

Many of these have also been published as research reports. Research areas, according to Cárdenas (2004), include topics as varied as approaches to language teaching, language skills, teaching aids (visual aids and computers), and curriculum.

In the case of the present study, teachers were immersed in a teacher development endeavor in the Colombian context since they were also in-service teachers who could apply the contents of the program to their daily teaching practice. Even though language issues as well as methodological training are important areas for teachers, and were taken into account in this study as ways to apply pedagogical issues on teachers' language development, we concentrated on networking and the collaborative work created by the participating teachers.

Collaborative Work among Teachers Working in groups is one of the landmarks in contemporary work relations of our society. Individuality can hardly be effective in a world where alliances and associations have to be attained in order to compete and gain major recognition.

However, these relations have to be built very carefully since "the group is for human beings a primary need and a primary threat at the same time" (Bonals, 2000, p. 5).

The seed of group work also has to be watered in the school since, as Imbernón (1997, p. 97) claims, "many collaborative efforts in the educational institutions may fail because some characteristics of collaborative work are not implemented". Some of these characteristics, according to the same author, are the following:

- Changing the kind of teaching staff development and getting a new organization based on collective interests

- Organizing working groups among teachers

- Establishing clear processes of educational collaboration in the school

- Improving the communication process among peers, including frequency and quality of interactions.

According to Imbernón, "the relationship between development and changing processes is given by the capacity of interaction among teachers" (Imbernón, 1997, p. 97).

One of the best assets of the updating program, in which this study was framed, had to do with the enhancement of group work among the teachers belonging to the same institution. The nature of the program was given by the understanding of the fact that no real change can be made in isolation. Santos Guerra, as quoted by Imbernón (1997, p. 102), gives us some insights in this direction when saying that "when a project is founded on the teacher's individual action in the classroom, the structures remain unchanged, they are neither transformed nor dynamized".

Benefits and difficulties of teacher collaboration

Inger (1993, p. 1) highlights that, although the current major educational reforms call for extensive, meaningful teacher collaboration, teachers "work out of sight and sound of one another, plan and prepare their lessons and materials alone, and struggle on their own to solve their instructional, curricular and management problems".

However, according to his research, conducted in different schools in California, Inger (1993) identifies some benefits and positive aspects from collaborative experiences. These benefits are as follows:

-There have been substantial improvements in student achievement, behavior and attitude.

- Collegiality breaks the isolation of the classroom, brings career rewards and daily satisfactions, and stimulates enthusiasm.

- Teachers who work closely together on matters of curriculum and instruction find themselves better equipped for classroom work

- Novice and inexperienced teachers benefit from experienced colleagues.

- Teachers take considerable satisfaction from professional relationships that withstand differences in viewpoints and occasional conflict.

- Teachers' teamwork makes the complexities of teaching issues (curriculum, classroom management, and so on) more manageable.

In spite of the several benefits outlined above, Inger also points out other aspects that become barriers and shortcomings when they are not adequately managed by the people involved in a cooperative project within the school. Among the barriers shown by Inger, the most important are:

1) the norms of privacy of teachers who are not accustomed to offering advice and support when they are not asked for it;

2) the departmental organization in which the only peer contact is given among teachers of the same areas and departments;

3) the barriers between vocational and academic teachers, which, in this study, can be paralleled to the barriers between secondary school teachers dealing with only one subject and primary teachers who usually have to teach topics of several subjects at the same time and with the same groups, and

4) the physical separation presented in schools like the one that is dealt with in this article.

Of course, the reader may find, when considering the analysis of the data collected during the process, other benefits and shortcomings that reflect the particular characteristics of the school and teachers participating in this work. In addition, other elements in this analysis may relate more to personal factors such as individual motivation and attitudes, which are not considered in Inger's work.

Previous works related to the topic

Different studies about collaborative teacher development activities have been made around the world. Here, I have talked about the experiences described by Imbernón in Spain and Inger in North America. Whereas Imbernón reports on the factors that impeded the attainment of the objectives stated by a group of teachers (Imbernón, 1997, p. 104), Inger analyzes the case of several schools in California in order to find out the benefits of and barriers to group work.

In Colombia, I found research done by Clavijo, Guerrero, Torres, Ramírez & Torres (2004) from the Universidad Distrital, who report on a teacher development activity carried out together with research group.

The researchers describe the process of primary and secondary teachers planning and implementing curricular innovation in their schools.

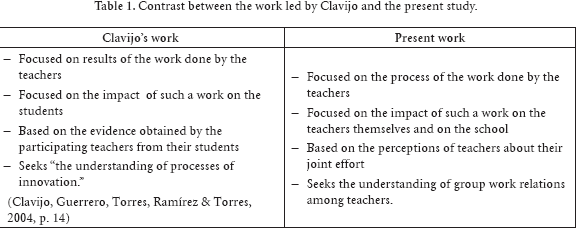

Their research is, therefore, quite similar to the research presented in this article in terms of the nature of the program, the participants and even the objective of the group work; that is, implementing innovations. However, the differences between the work led by Clavijo et al. and the one presented here lie in the following aspects:

Cárdenas (2002) also shows how teachers' collaborative efforts, particularly to establish teachers' communities, are vital in the formation of teacher study groups, which will ultimately settle permanently to bring permanent change to schools in the shape of ongoing innovation, research and academic improvement for the whole school community. In this way, the challenge is not to have teachers work collaboratively, but to keep on doing so by forming steady groups of researchers who can think about their own pedagogical and professional challenges, question their own daily practice, and conduct action research to better the teaching and learning processes.

The Resource Center and Its Basic Principles

The use of resource centers in ELT practices is currently the object of a great deal of teaching-learning studies. (table 1)

istorically, resource centers caught the attention of many people even as early as the 70s. Nowadays, the concept of Resource Center that we usually find is similar to the one expounded on in MEMFOD (2005, p. 4) of "a total space, integrated to educational centers and prompter of regional cultures.

Resource centers are thought to be promoters of the teaching-learning process by enhancing pedagogical renewal and facilitating autonomous learning through a varied gamut of didactic materials".

The resource center, thus, is not just an organized collection of bibliographical, didactic or technological material that is categorized and classified according to determined criteria. What is important here is the pedagogical principle that is being developed through all those resources and tools.

The teachers involved in this study, then, had to study some of the most important concepts and philosophies embedded in the use of resource centers.

Benavides (2000), when talking about these principles, particularly mentions the notion of autonomy -which was also fostered implicitly as well as explicitly in the sessions of language development and methodology-, CALL (Computer Assisted Language Learning) and curriculum adaptation to include the resource center in the school environment. Even though every principle is fundamental in the setting up of language resource centers, the notion of autonomy seems to be the most complex, given the fact that it is not only a way of learning, but also a way of living. Lagos & Ruiz (2007), in their research, found many implications for autonomy that affected students and their beliefs and perceptions about autonomous work.

In order to figure out how the language resource centers were to be implemented in the school, the program counted on the valuable experience of ALEX (Program for the Development of Autonomous Foreign Language Learning) in La Universidad Nacional, whose tutors explained in detail basic principles to implement a resource center.

Methodological Framework

As the main interest of this work was to get a better understanding of group relations among a specific group of teachers, case study research allowed for the study of "the peculiarity and complexity of a singular case in order to figure out its activity in important circumstances" (Stake, 1999, p. 15).

Perhaps the best justification that I can offer for the use of case study is clearly stated by Stake (1999, p. 15) in this enlightening paragraph:

The cases that are interesting in education and social services are mostly constituted by people and programs. People and programs are similar in a way, but they are unique as well. These cases are interesting [to case study researchers] for their uniqueness as well as for their commonalities. We intend to understand them. We would like to listen to their stories.

Perhaps we may have some reservations about what people tell us; similarly, they may be suspicious about some things we say about them. However, we come into stage with the sincere interest to learn how people work in their habitual environments, and with the willingness to leave aside many presumptions while learning. The main characteristic of case studies is that they focus on a unique and particular case, and look deeply into it in order to acquire a profound knowledge of how this singular case works in a determined situation without paying much attention to surrounding situations and activities. In other words, case study "represents depth of information rather than breadth" (NOAA Coastal Services Center, 2005, p. 3).

Methodological Design

In order to come up with the written proposal, the participating teachers agreed on six objectives and started to work in groups of branches and shifts so that they could develop each of the objectives. Each group was in charge of one objective and had to establish schedules and actions to achieve it. The objectives to be achieved were 1) To design the resource center of the school in all shifts and branches in order to support the English language teaching process; 2) To create pedagogical strategies to promote the students' autonomous learning through the use of the resource center; 3) To involve all teachers in the school so that they can / will also support the resource center; 4) To sensitize the school community about the existence and use of the resource center; 5) To administer the resource center; and 6) To support the development of the four communicative skills in the resource center.

Instruments for data collection

A survey was the instrument that informed us about the difficulties and benefits that teachers went through during the process, the way they faced the difficulties and the possible problems in the future. It also gave us ideas about the perceptions and beliefs teachers had about the program and its product. This was applied to the majority of teachers from the different branches or sites (sedes A, B and C) and shifts (morning and afternoon) of the school.

Interviews were also carried out to look more deeply into the results of the survey and to offer insights into more personal perceptions and specific data. This instrument was applied to one member in every group in charge of a specific objective. Each group selected a spokesperson to respond to the interview. The questions formulated for the interviewees were the following:

- How do you feel about the process that has been undertaken in order to come up with a resource center project in your institution?

- How has the interaction with the other members of your group been?

- What kind of difficulties have you found in this work? Personal? Professional?

- Which advantages?

- Have these difficulties been completely overcome? How?

- How have you contributed to group work?

- Do you think that the process of group work has contributed to your personal and professional life? In which sense?

- Would you like to add any other aspect that has not been dealt with in this interview? Field notes were also taken in the meetings provided within the program at the university and in the meetings held during the in situ visits in the School.

Mostly, the field notes were prepared in order to provide ideas about the steps given in every meeting and about the interaction and group relations among the teachers.

All in all, the first two instruments show the perceptions of the teachers about the process they underwent. In contrast, the third instrument contains the perceptions of the researcher, which provide a balance between inside (the participating teachers' views) and outside perceptions (the researcher's view) that helps assure different perspectives of the same phenomenon.

Whenever I refer to samples taken from any instrument in the research findings section, it is referred to as follows:

(Surv.): Survey

(Int 1, Int 2, Int 3, Int 4): Interviewee 1,

Interviewee 2, Interviewee 3, Interviewee 4

(FN 1, FN 2): Field Notes 1, Field Notes 2.

Data Analysis and Research Findings

Data were collected throughout a five-month period, in which there was a follow-up of teachers' interactions in the updating program, in the university and in their own school. To do the follow-up, we took advantage of the sessions that were scheduled in the university as well as of the in situ visits to the school. In the present study, methodological triangulation was used as a way of validating the research outcomes and results. The notion of methodological triangulation that was taken into account here is similar to the one stated by Denzin, as mentioned in Clavijo, Guerrero, Torres, Ramírez & Torres (2004), as the process of the combination of multiple techniques of data gathering such as observations, interviews, and others with the purpose of achieving validity.

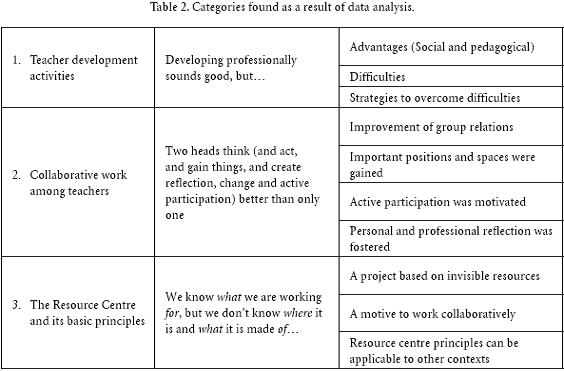

After comparing the different results drawn from the processing of data obtained from each instrument, it was found that most of the collected information had a direct connection to the theoretical constructs that guided our study, namely, teacher development activities, teacher collaboration and resource center implementation. Consequently, each category also reflects these relations, as shown in Table 2.

Developing Professionally Sounds Good, but…

The results of this study suggested that when teachers decide or are encouraged to be part of teacher development programs, they not only find a lot of advantages and help, but they also have to face several difficulties and challenges and have to look for strategies that allow them to overcome these difficult and challenging situations.

The analysis showed that social and pedagogical advantages of teacher development were the most acknowledged by teachers. Social and personal skills such as communication, respect for others' ideas and listening abilities were the most important. As described by some teachers, the "relationship with other teachers has improved" (Survey). Similarly, when asked if they thought that the process of group

work had contributed to their personal and professional life, one teacher said:

"Yes, of course. Nowadays, for example, we not only work on the resource center, but, well, we have learned that the most important thing was communication as such". (Int 2)

Pedagogical advantages were also touched on, as responded by the same teacher:

"I feel myself more spontaneous when teaching English. I have gained self-confidence". (Int 2)

Given that the advantages of teacher development activities are obtained after the overcoming of several obstacles, teachers also mentioned very often a number of difficulties seen during the process as well as the strategies they used to advance through their tasks. The most frequently mentioned difficulties have to do with lack of institutional support, either from colleagues at the school or from administrative staff, limited time, and mobility among teachers.

The first two difficulties are dealt with in the intervention of a teacher during the interview:

"I wish that the administrative staff, and more specifically, the principal, were more in contact, more in contact with the resource center, so that she realizes all the things we need, especially time..." (Int 4)

As an observer, I also noticed that

"they found problems in agreeing on a schedule so that every member can attend. However, the teachers that could attend the meetings, worked together in order to have a report ready for the meeting". (FN 1)

Changes in positions and mobility of teachers, which are very common in the public sector, were also regarded as great limitations for conducting collaborative endeavors, as pointed out by another teacher:

...It means that the former principal was involved in the program. Afterwards, she was moved, and a process of transition came for us to know the new principal…so the administrative procedures are going to be a problem in the implementation of the resource center. (Int 3)

Regardless of the different problems presented by teachers, it was also noticeable that they, as creative and innovative agents, were able to overcome difficulties by using different strategies according to the problems that appear in any pedagogical process. Devoting personal time, activating emotional links with the school and engaging in dialogue and negotiation with administrative staff appeared among the most successful strategies.

Two Heads Think (and Act, and Gain Things, and Create Reflection, Change and Active Participation) Better than Only One

Despite the multiple problems and difficulties presented when teachers engage in teacher development programs, some of which were delineated above, the participating teachers paid more attention to the personal as well as professional benefits of group work.

Teacher development programs that are based on teacher collaboration and group work are more likely to create and improve the relationships of teachers inside as well as outside the school. Programs of this nature evidence essential social and intercultural skills such as harmony, respect, negotiation of differing agendas, dialogue, etc, as commented on by one of the participants:

Of course, it has been good because we know each other for a long time, there is harmony, respect, support...Besides, we are committed to this job because there is friendship, and with friendship the outcomes are better and the work to be done inspires more commitment. (Int 3)

In addition to the renewal of relations within the group of teachers, it was evident that collaborative work does have a real impact on the school structures and practices. In this case, the endeavors of teachers resulted in the gaining of acknowledgment in the school as well as a better negotiating position, regardless of other difficulties that may arise:

"Some opportunities of socialization have been gained but, still, apathy is a common feature among some colleagues". (Survey)

Talking about the role teachers have played in group work, participants showed a favorable move into activeness and participation. When teachers were asked in the survey about their role in their own group's work, their responses showed that most of them thought of themselves as active participants fulfilling different roles such as leader, reporter, spokesperson, etc.

Furthermore, one of the most interesting outcomes of this case of collaborative work was that, when working in groups, teachers were able to reflect upon their own individual performance, to analyze the contributions from their colleagues and to implement suggestions and strategies used by others in order to apply them to their pedagogical settings with satisfactory results. This perspective is clearly stated here by one of the interviewees:

Gathering with other people makes the work to be enriching, doesn't it? In other words, when hearing the contribution of another person, one says: 'Well, so I can do this too…' Then, There is a mutual enrichment...we have learned from the other, from the others' experience... (Int 3)

We Know What We Are Working for, but We Don't Know Where It Is and What It Is Made of…

The primary goal of this specific case of teacher development activity and teacher collaborative endeavors was the resource center. The center and its principles influenced teachers not only as a possible innovative tool to better the pedagogical processes in the school, but also as a way to explore new alternatives to improve classroom practices and social relationships of teachers, students and administrative staff.

Nevertheless, one of the most important difficulties found by the teachers in the construction of their proposal was that they were working on a project based on resources they had not seen. Thus, apart from the difficulties shown above, the doubts about the resource center, its elements, administration and materials, which had not been introduced to the teachers, impeded a better and more realistic project. Thus, teachers had to work on something unknown and blurred. Despite their good performance in the process, it was by far the most recurrent complaint:

And we have this problem of the resource center within the institution because it arrived at the school, and afterwards it was taken out again...in other words, we haven't had the opportunity to know what the materials and components of the resource center are. (Int 1)

The lack of information about legal and administrative procedures was a big constraint.

This information and data must be provided by the school administration and by the Secretary of Education. This information had to do with the stock of the resource center, the person to be in charge of it, and the security devices to be used in the Resource Center. (FN1)

Despite the issue previously mentioned, the resource center, in addition to being the final goal of this program, was regarded as a justification to work collaboratively in the school and establish new bonds among teachers, as one of them put it: "Eh, because we are interested in the resource center working in the school, for the benefit of the students as well as of ourselves" (Int 2).

Moreover, teachers in the program understood that the principles and philosophies underlying the resource center can be extrapolated to other contexts, fostering autonomous learning and the use of different sources of information to improve students' communicative competence:

This project has contributed to my profession because, apart from the fact that we learn to work collaboratively, we have kept on working autonomously, and we apply this manner of learning to practice, in the classroom and with oneself... (Int 3)

Limitations

This work has basically the same limitations that are likely to appear in any case study. It shows a unique case among many others, which is a feature that weakens the possibility to make generalizations, even when other cases may have similar characteristics. Nevertheless, as noted by Stake, it is important to understand that "from particular cases people learn about many things which are general" (Stake, 1999, p. 78). Another limitation of this study is that of the relativity based on the personal viewpoint and interpretation made by the researcher; that is, different researchers may find different things in the same scenario. In addition, attempts to apply the results of a particular case study to others are quite restricted because the nature itself of case studies is to delve into the features and aspects of a single case.

In terms of data gathering techniques, although every technique was carefully selected in accordance with the time and other conditions of the study, I felt at certain moments of the inquiry process that some other things such as video recordings of teachers' interactions or a longer observation process could have been implemented in order to give a clearer and less subjective perspective of the case.

However, more instruments, artifacts and methodological tools would have meant more time and more interpretation too. Nevertheless, the information shown here can be regarded as the basic triangulation needed to obtain validity and reliability.

Conclusions

The study that has been presented on these pages is a factual example of the existence of teacher development activities in Bogotá and evidence of teachers' willingness to create positive change in schools. The project that was carried out by the participating teachers, in particular, is among the most complex. In the words of Bonals, "building the educative project of the school, making the objectives fit into students' levels or harmonizing work styles are supposed to entail the major difficulties" (2000, p. 43).

However, these "major difficulties", as shown in this project, are better handled when teachers work collaboratively and strive together to attain common goals. In this particular case, thanks to a collaborative endeavor, participants were able to present a comprehensive and coherent proposal to set up the resource center of the school by putting together their views regarding each objective and by discussing the results of each group's efforts. Gradually, educational authorities and theorists have acknowledged the constructive role of collaboration as opposed to competition in the achievement of pedagogical innovations within educative institutions. The case presented here should reaffirm this perspective.

It is important to highlight though that a follow-up of teacher development activities (the resource center, in this case) needs to be implemented. When no followup is implemented, educational authorities, universities and school administrations cannot keep track of the outcomes and results of teacher development activities, are unable to evaluate them and, as a consequence, educational processes remain obsolete.

In any case, all the aspects mentioned throughout this study cannot be adequately understood without looking at the crucial notion of professionalism. At a time when teachers are regarded as mere employees facing the same problems that are common to any other professional, it is important to show them that they are knowledge creators and promoters with a high scientific potential, rather than being solely 'syllabus performers' and followers of others' ideas.

Teachers' professional obligations go far beyond the reproduction of given models without reflection and analysis (Imbernón, 1997, p. 145).

Pedagogical Implications

The present study attempts to offer researchers, program coordinators and university tutors a close view of what may happen when teachers get together to work collaboratively in the school. The perspective presented in this work can give program administrators some clues for them to adapt, improve or qualify the preand in-service programs that they plan and develop, based on collaborative skills and abilities.

In schools, principals and coordinators are often happy when teachers undertake actions in order to improve the academic situation of the institution. However, they are sometimes reluctant and rigid when teachers ask them to arrange spaces and time in the academic schedule to develop the activities planned to initiate innovation or research in the school, even though some committed teachers are willing to devote personal time and extra efforts. These personal efforts need to be acknowledged, valued and supported by the school. By examining the case that is depicted on these pages, school managers should ask this question: If teachers without much support and resources are able to attain such great things for the school, how would it be with full institutional support?

Finally, the message sent to school teachers from this study seems to be clear: Regardless of all the difficulties they might find when working with colleagues, it is certainly worth it. When teachers learn that they can do more beyond their regular classes, their professional and personal self-esteem will increase to a large extent and their work atmosphere improves too. Through the work that was observed, it was detected that the teachers' attitude towards the teaching profession was improved. Thus, this study aims to transmit the same attitude to the readers by showing them an endeavor that was successfully made by people with perhaps more social and work-related challenges than average teachers.

Further Research

Bonals (2000) gives us some ideas for conducting further research when he highlights that there is a new and unexplored field for those involved in school consultancy, which encompasses, firstly, the preparation of trainers and tutors to enhance teachers' networking, and secondly, the acknowledgment of the real importance of teachers' interpersonal skills and teamwork on the side of the school administrations. These two aspects will be crucial in the improvement of group relations and pedagogical processes at school and, consequently, in the improvement of education in the country.

It would be worth conducting research concerning the enhancement of group work among teachers either in the public sector or in the private one.

* This paper reports on a study conducted by the author while participating as assistant to the PROFILE Research Group during the development of the Programa de actualización para el uso pedagógico de los centros de recursos de idiomas en la Localidad Cuarta de San Cristóbal, in 2005. The program was sponsored by Secretaría de Educación de Bogotá, D.C. Code number: 30102004391, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Humanas.

1 This program held as its main objective to update teachers in pedagogical and practical uses of resource centers, which also included new methodologies and approaches to the teaching of English as well as the philosophies and fundamentals of these centers.

References

Bonals, J. (2000). El trabajo en equipo del profesorado. Barcelona: Editorial Grao. Benavides, J. (2000). CALL, self-access, and autonomous learning. HOW. A Colombian Journal for English Teachers, 116-118. [ Links ] [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. L. (2002). Teacher research as a means to create teachers communities in inservice programs. HOW. A Colombian Journal for English Teachers, 9, 1-6. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. L. (2004). Classroom research by inservice teachers: Which characteristics? Which concerns? Research News, 3-7. [ Links ]

Grupo de Investigación PROFILE y Programa de Desarrollo del Aprendizaje Autónomo de Lenguas Extranjeras - ALEX (2004). Programa de actualización para el uso pedagógico de los Centros de Recursos de Idiomas en IEDS de la Localidad de San Cristóbal. Propuesta presentada a la Secretaría de Educación de Bogotá, en convocatoria pública de diciembre de 2004. Bogotá: Mimeo. [ Links ]

Clavijo, A., Guerrero, C. H., Torres, C., Ramírez, M., & Torres, E. (2004). Teachers acting critically upon the curriculum: Innovations that transform teaching. ÍKALA, 9(15), 11-41. [ Links ]

González, A. (2003). Tomorrow's EFL teacher educators. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 86-99. [ Links ]

Imbernón, F. (1997). La formación y el desarrollo profesional del profesorado. Barcelona: Editorial Grao. [ Links ]

Inger, M. (1993). Teacher collaboration in secondary school. Retrieved August 5, 2005, from NCRVE National Center for Research in Vocational Education CenterFocus Web site: http://vocserve.berkeley.edu/centerfocus/CF2.html [ Links ]

Lagos, J. & Ruiz, Y. (2007). La autonomía en el aprendizaje y la enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras: una mirada desde el contexto de la educación superior. Retrieved March 25, 2008, from Revista Electrónica Matices en Lenguas Extranjeras, 1. Web site: http://www.revistamatices.unal.edu.co/numero1.html [ Links ]

Molina, O. (2000). Teacher training: A multifaceted framework in language learning. HOW. A Colombian Journal for English Teachers, 84-94. [ Links ]

MEMFOD (2005). Programa de Modernización de la Educación Media y Formación Docente. Retrieved July 3, 2005, from MEMFOD Web site: http://www.memfod.edu.uy/pages/acerca.php [ Links ]

NOAA Coastal Services (2005) Case Study Research. Retrieved March 27, 2006, from Social Science Methods for Marine Protected Areas Web site: http://www.csc.noaa.gov/mpass/tools_casestudies.html [ Links ]

Richards, J. & Nunan, D. (1990). Second language teacher education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Stake, R. E. (1999). Investigación con estudio de casos. Madrid: Morata. [ Links ]