Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile no.10 Bogotá July/Dec. 2008

Professional Development Schools: Establishing Alliances to Bridge the Gap between Universities and Schools

Escuelas de desarrollo profesional: creando alianzas para reducir la brecha entre colegios y universidades

Claudia Torres Jaramillo*, Rocío Monguí Sánchez**

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

* E-mail: ctorresjaramillo@yahoo.com

Address: Avenida Ciudad de Quito No.64-81 oficina 607. Bogotá, Colombia.

Fundación Santa María** E-mail: rociomongui@yahoo.com

Address: Cra. 109 A No. 81 A 80 Casa 13 Barrio Bulevar de Bolivia. Bogotá, Colombia.

This article was received on October 31, 2007 and accepted on August 9, 2008.

This article narrates the way a Professional Development School (PDS) got started. PDSs refer to alliances among educational institutions that join forces and resources to provide community members high quality services and products. Two stages are depicted. The first one deals with the setting up of human and material resources, identifying ways of collaboration among institutions and defining the roles of every partner involved. The second stage has to do with the implementation of the proposal per se, the obstacles faced and the action plans to carry on with the implementation. Partial findings and outcomes of this PDS-in-progress are shared with the hope of promoting the PDS concept in our community by means of establishing more partnerships, receiving feedback from experienced peers, and establishing networks.

Key words: Professional Development Schools -PDS, partnerships, cooperation, collaboration, practicum

Este artículo narra el proceso de implementación de una Escuela de Desarrollo Profesional (PDS). Las PDSs se entienden como alianzas entre instituciones educativas que unen fuerzas y recursos para brindar alta calidad y servicios a los miembros de la comunidad. La experiencia se presenta en dos etapas. La primera describe la organización de los recursos humanos y materiales, identificando formas de colaboración entre las instituciones involucradas y definiendo los roles de cada participante. En la segunda etapa se expone el desarrollo de la propuesta, los obstáculos que se enfrentaron y el plan de acción que se siguió. Se presentan los resultados obtenidos hasta el momento, en la perspectiva de promover el concepto de PDS en nuestra comunidad académica a través del establecimiento de más alianzas estratégicas, de la retroalimentación de colegas experimentados y redes de trabajo.

Palabras clave: Escuelas de desarrollo profesional, alianzas estratégicas, cooperación, colaboración, practica docente

Introduction

Professional Development Schools (PDSs) are innovative types of partnerships between universities and schools designed to bridge the gap that exists between them. Their mission is to bring about the simultaneous renewal of school and teacher education programs to improve student learning and revitalize the preparation and professional development of experienced educators at the same time. PDSs starts with the premise that the additional time and effort to try to work across two or more organizations is worthwhile compared with trying to achieve the same goals internally (Teitel, 2003).

This article is written as a narrative grounded in Dewey's educational philosophy, which at its core argues that "we are all "knowers" who reflect on experience, confront the unknown, make sense of it and take action" (Dewey, 1916, 1920, 1933; cited in Johnson & Golembeck, 2002, p. 4). The authors of this article are teacher researchers who worked together on the project - one as the on-site coordinator at Fundación Santa Maria school (FSM) and the other as a professor holding a master's degree at Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas (UD). We tell the story of how this concept was put into practice at FSM school in alliance with UD. In this setting, this is a new idea and can be considered an innovation in the educational field.

Narratives, by their very nature, are social and relational and gain their meaning from our collective social histories. They cannot be separated from the sociocultural and sociohistorical contexts from which they emerge and they are deeply embedded in sociohistorical discourses as stated by Gee (1999) and Johnson & Golembeck (2002, p. 5). How we reflect on experience and how we make sense of it is often achieved through the stories we tell. Narrative has been constructed as a mode of thinking (Bruner, 1996, p. 15) and as a means of representing the richness of human experiences (Johnson & Golembeck 2002, p. 4). As Bruner, in Jurado (1999), points out, we narrate because our thinking process demands us to do so; we feel the need to name our experience and to organize it because we want to influence the world of others. Narratives help us to open up, to fulfill the desire to communicate and are the means by which we can persuade and convince others. According to Johnson & Golembeck (2002, p. 7), our stories, as teachers, reveal the knowledge, ideas, perspectives, understandings and experiences that guide our work. Our stories describe the complexities of our practice, trace professional development over time, and reveal the ways in which we make sense of and reconfigure our work.

From our experience as educators in different settings in Bogotá, we came to the conclusion that the possibilities that PDSs offer are vast and valuable. The fact of having academic institutions joining forces with common goals opens many doors for professional development, qualification of students, shared resources that can be enhanced and improved, and more options to be explored, enriched and implemented according to every institution's needs.

This is the main reason for our interest in sharing with the academic community our experience in implementing a Professional Development School.

In order to put into practice this PDS concept, two institutions collaborated to establish objectives, procedures and possible alternatives for cooperative work. Once this collaboration was achieved, two stages were developed. The first stage dealt with developing a proposal for the setting up of human and material resources, identifying ways of collaboration between institutions and defining the roles of every partner involved. The second stage had to do with the implementation of the proposal as such, the obstacles faced and the action plans to carry on with the implementation.

Partial findings and outcomes of this PDS-in-progress are shared with the hope of promoting the PDS concept in our community by means of establishing more partnerships, receiving feedback from experienced peers, and establishing networks. We believe that this experience will open doors and lay the ground for academic institutions to look more closely at how they can work together to tackle better the challenges that they face in education.

Rationale

In Colombia, according to our experience, there has been a significant change in the approach by universities and schools towards the teaching practicum. During the 1990s the practicum as part of the teaching programs was seen as a very important component and, thus, the university was responsible for contacting schools that would be willing to accept practitioners, but it was not an easy task.

Many schools were reluctant to accept practitioners as they felt observed and judged by universities since these higher education institutions were considered the holders of knowledge. This situation reflected the need for establishing stronger relationships that would allow collaborative work and the possibility of developing research among universities and schools. As Teitel (2003) points out,

"hybrid institutions formed by university and school partners can bridge the gap between the sectors and between theory and practice. They can facilitate renewal in both school and university as a result of knowledge shared in the partnership. Most important, they can enhance both teaching and student learning" (p. 9).

Another factor that has contributed to broadening the gap between schools and universities is explained through the behaviorist and the traditional craft paradigms that have influenced teacher education not only in the US but also in contexts like ours. Zeichner (1983, p. 3) presents these two paradigms in which students are taught certain skills technically and expected to develop a certain mastery of them. It is through imitation of a model, somebody with plenty of experience, that they can be regarded as effective in their jobs. These two paradigms have been very popular in the case of pre-service teacher training since they allude to practitioners as empty vessels which need to be filled. Thus, practitioners are regarded as completely or partially lacking pedagogical knowledge and, therefore, need to be told exactly what to do and how to perform their practice (Viáfara, 2004, pp. 10-11).

From the numerous factors that hinder relationships between schools and universities we experienced another situation in this PDS that created tension among mentors and student teachers. The benefits school teachers identified in regard to having practitioners did not necessarily have to do with professional development.

Instead, in many cases they saw the fact of having practitioners as a means for catching up with their duties or for having some free time; many times teachers left the classroom when practitioners came in and these were left to face the classes on their own without proper training and self confidence to do so in an effective way. This situation did not contribute to developing collaborative relationships between in-service and preservice teachers. Therefore, it is necessary to find a balance between the opposite and extreme positions discussed above regarding the role of the practitioners and mentors in order to make the practicum a fruitful, enjoyable and enriching experience for all the parties involved.

A number of authors have discussed the personal and idiosyncratic nature of the cooperating teacher / student teacher relationship and too often this relationship is plagued by tensions and power conflicts due to different life histories and personalities of the two actors (Agee, 1996; Graham, 1993; Sudzina, Giebelhaus & Coolican, 1997, as cited in Vélez-Rendón, 2003, p. 18). Even though changes have taken place in regard to the view held towards the practicum in our context, still today, in some cases, student teachers are not seen as professionals with the growth that would allow them to contribute with their knowledge to the development of the institutions where they carry out their teaching practice. "Students teachers are told what to do in their lessons to teach appropriately and they are expected to do exactly that in order to be considered successful. Therefore, the opportunities for practitioners to develop their own knowledge as well as the tools to keep examining that knowledge seem to be reduced" (Viáfara, 2004, pp. 5-6).

According to Viáfara (ibid.), it is our duty to provide student teachers with valuable opportunities to build their own knowledge. Our practitioners are not empty vessels; they have been learning and accumulating knowledge for many years, in different ways, and from various sources.

Our role as teacher educators should be based on respect and guidance, supporting practitioners in their development of an inquiring attitude so that they are encouraged and prepared to explore several issues of the pedagogical task.

Unfortunately in this PDS, some student teachers1 missed valuable opportunities to receive feedback and support in this difficult task that they undertook and, at times, in-service teachers did not take advantage of the chance to invigorate their teaching practice and share ideas and experiences in relation to academic and pedagogical issues.

In this article we are going to narrate the way we started the implementation of a PDS in a setting in which this is a new idea and can be considered an innovation in the educational field. As Jerome Bruner (1996) points out, we narrate because our thinking process demands us to do so.

We divided the story into three parts to facilitate its understanding; the first one is Preparing the Ground, where we tell the readers how the setting was organized to start the implementation. The second part is called Getting Started. It narrates the way this project got off the ground. Finally, in the Hands on Experience section, we describe the process that has taken place up to now, the obstacles encountered and how we have coped with them. We conclude with some insights drawn from this enriching experience.

Preparing the Ground

There are some initial considerations that need to be taken into account when starting the implementation of a PDS.

Key people who are highly committed and believe in such a project as well as who are able to motivate, persuade and guide others towards achieving the same objective are needed. Furthermore, it is necessary to count on school and university partners who are open-minded, who are willing to innovate their teaching practices by interacting and sharing knowledge, experiences and views about education and who have the support of key institutions which are willing to help in such an endeavor.

In order to put into practice this PDS concept, which was an innovative proposal in our specific context, people were gathered to establish objectives, procedures and possible alternatives for cooperative work. Once this was achieved, some phases were developed. The first phase deals with the setting up of human and material resources, identifying ways of collaboration between institutions and defining the roles of every partner involved. The second phase has to do with the implementation of the proposal as such, some of the obstacles encountered and the action plans to carry on with the implementation. We believe that this experience will open doors and lay the groundwork for others in Colombia and Latin America to look more closely at how universities, schools and other entities or educators can work together to tackle better the challenges faced in education.

Although the school where the PDS was proposed to be implemented does not have enough resources to sponsor new projects, there were people and organizations interested in supporting a project that would contribute to the effective teaching and learning conditions of this population, and such was the case of the Board members of Fundación Santa María school.

They believe that children with limited resources should be given the opportunity to learn English the same as the sons and daughters of elite families. Nowadays in our country, as in any other part of the world, it is necessary to learn English in order to be able to access a globalized world. Thus, the school had the initiative to hire an English teacher to start the process of implementing English in the school's curriculum.

The Board members of FSM school realized the benefits of having an alliance with a university that would have an undergraduate teaching program with an emphasis on English and on making the connection in order to have practitioners who would reinforce the work that was being done at the school.

Getting Started

In order to start this innovative project, two institutions got together to explore possible alliances. These institutions believe that education should offer better opportunities by means of providing equity within society, and that partnerships can be established among educational entities.

The types of institutions that participated in these meetings were a nonprofit foundation that provides education services to children with limited resources in preschool and primary levels (FSM school), and a public university that is sponsored by the district and provides higher education (UD university). These two institutions established the partnership.

Alliances require, from the parties involved, identifying strengths and weaknesses, exploring different ways of working cooperatively and establishing specific roles. As mentioned by Teitel, "Roles in beginning PDSs tend to be flexible, as PDS advocates feel their way into the work" (Teitel, 2003, p. 68). As the project evolved and the parties became more familiarized with working collaboratively, the roles were more clearly defined.

The role of the school

FSM school assumed various roles like coordinator, facilitator, and mediator. It was necessary to have an institution that would manage the whole process and the school undertook the role of coordinator. In order to do so, the holder of a master's degree in the field of Applied Linguistics to the teaching of English was hired by FSM school to act as the on-site coordinator of the PDS. This person was in charge of planning, implementing and assessing the whole process and was constantly providing support to the parties involved.

In relation to planning, the on-site coordinator was responsible for organizing the meetings with the university and school representatives so as to start a fruitful relationship. These meetings were carried out in order to inform the parties about the principles underlying the PDS and the way to implement it. The meetings took place both at the university and at the school in order for the practitioners, mentor teachers and administrative staff to feel equally treated and valued. The objective of doing so was to balance out the higher status given in our context to universities in regard to schools.

Regarding the implementation, the on-site coordinator kept a written record of every meeting held with the objective of first, identifying needs and difficulties encountered by the members of the partnership; and second, establishing agreements and entrusting responsibilities.

Furthermore, there was a constant followup and support for student teachers as well as mentors. This support is fundamental in order to guarantee that every member is familiarized with the procedures and is working towards the same goal. Finally, the on-site coordinator needed to assess the process to make sure that all the actions taken contributed to the success of the PDS.

Additionally, the school -FSM- took on the role of facilitator by providing the human resources such as administrative staff, the PDS on-site coordinator, mentor teachers and students. It also contributed with resources such as the place in which the project was carried out, equipment and didactic material, among other items.

The school also assumed the role of mediator bridging the gap between the school and the university, parents, students, practitioners, mentors and administrative staff. This was achieved by means of various activities, such as organizing workshops for parents which allowed them to meet each other and share their expectations in regard to their children's education; these workshops also helped parents understand the learning processes their children were going through at school. Parents were required to do the same sort of activities their children did, so that they would comprehend the purposes behind these tasks and collaborate with their children's education at home. In these workshops, mentor teachers were leaders as they were the most experienced in handling these activities. Practitioners also participated actively in the organization of the workshops, gaining experience in the development of this type of events.

Another activity was the application of a survey with the mentor teachers to find out more about their studies, previous teaching experience, abilities and talents. Once the information was gathered and key aspects were identified, the on-site coordinator designed workshops for members of the academic community. For instance, if a mentor teacher was good at making flower arrangements, she would teach a workshop for those members of the community interested in learning about this activity. The intention behind this type of activities was to benefit from the knowledge, experience and abilities found among the teaching staff.

The role of the university

In relation to the public university -UD- it assumed the role of facilitator. On the one hand, the undergraduate program provided the student teachers, who carried out the pedagogical interventions and developed small scale projects at FSM school as part of their teaching practicum.

Moreover, the university opened spaces for mentor teachers to continue growing professionally by inviting them to attend or participate in seminars, conferences and workshops.

On the other hand, the Master's Program collaborated in designing a research project that would be carried out along with ESPERE, a non-profit foundation which bases its work on emotional literacy, implementing a method that provides training for the transformation of accumulated anger, hatred and the urge for vengeance. The foundation's work focuses on conflict resolution and the achievement of sustainable peace by means of forgiveness and reconciliation2 .

With this project, FSM school intended to train teachers from the public school sector in conflict resolution strategies, the development of tolerance and the acceptance of diversity among students and the community in general. In addition, the Master's program in Applied Linguistics motivated its students to plan and start their theses in areas that would have an impact on the school's curriculum.

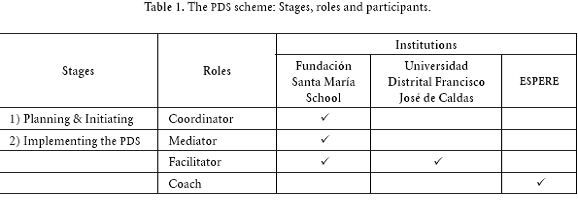

The table 1 below shows the stages the PDS went through and the roles that each institution assumed.

Hands-on Experience

Research in the educational field has demonstrated that the first five years of teaching practice are fundamental to developing pedagogical skills that usually prevail throughout teachers' professional life. After some time teachers tend to become alienated by the system and, in many cases, do not engage in professional development courses and programs. Thus, policies and projects are needed that help consolidate the teaching profession within society (El Tiempo, 2005, p. 2). Teaching has to perpetuate constant learning. Only if in- and pre-service teachers understand that especially in this field we need to be constantly studying, learning, sharing and taking full responsibility for our actions, will we provoke significant and positive changes in education.

This perspective of the teaching practicum in our country contributed to our desire to promote changes in this field and the principles that underlie the PDS became an appealing and valuable alternative to be adapted to our setting.

Thus, FSM school and UD university, being aware of the relevance and importance of PDSs, committed themselves to put into practice this project. To start, the onsite coordinator set up the appropriate conditions for the practices to take place. Then, she informed all members of the school about the project that was going to be implemented so that everybody would feel involved and motivated to cooperate; she did so by organizing schedules, preparing the induction of student teachers, mentor teachers and university professors as well as receiving and evaluating student teachers´ proposals for classroom interventions, among others.

A fundamental aspect, mentioned above, that helped to set the ground to create a positive atmosphere for the implementation of the PDS, was the role of the on-site coordinator. She sensitized mentor teachers in relation to the traditional idea of teaching practicum versus the new perspective PDS provides. It required constant dialogue, support, and a follow-up with mentor teachers throughout the time in which this PDS was implemented. In order to set the ground for this appropriate environment, several actions were taken.

On the one hand, the PDS on-site coordinator recognized and expressed that mentor teachers needed to be listened to, taken into account and supported in their initiatives, ideas and projects. This implied not only recognizing their potential but also valuing their experience and knowledge, all of which helped raise their self esteem.

Mentor teachers were also motivated to share their experience with others by taking the risk to write about their teaching practice and publishing it or presenting it in academic events. As noted by Benson (2000, in Cárdenas, 2003, p. 60), "publishing is a way for members of the academic community to share ideas and possibly contribute something to the world's store of knowledge. To publish is to engage in a dialogue with unseen and often unknown others".

Besides, the on-site coordinator contributed to raising awareness about the benefits that the strategic alliance with the university offered mentor teachers.

Advantages included the possibility to attend and participate in academic events, take courses at the university, and be in close contact with university professors, student teachers and administrators. Additionally, within the school schedule a time was set aside for mentor teachers to gather and reflect upon their teaching practice. These meetings helped mentor teachers to value the school efforts to promote an in-depth transformation. Teachers expressed that the fact of having practitioners at the school had been very enriching as it allowed them to observe, analyze and reflect carefully about their teaching, their students and even their own colleagues.

This coaching was very valuable in encouraging mentor teachers to assume an active part in the project. They recognized the key role they played in the process, which promoted ownership. Moreover, mentor teachers showed a very responsible and caring attitude towards their children in relation to the activities that they were to develop. Such attitudes evidenced how deeper reflection was taking place among mentor teachers, partly due to the fact of having practitioners observing and supporting their classes. This issue also appeared in Faith's study (2004), when she claims that there is ample evidence that mentors were prompted to think deeply about how and what they were teaching as well as why, and to try to use more effective strategies and instructional techniques when they worked with the MET students (p. 438).

Fostering Practitioners' Sense of Belonging to the Institution

When practitioners arrived to FSM school, they were given time to become familiarized with institutional documents so that they could propose pedagogical interventions in light of the children's needs, existing state educational laws, policies and principles of the school (PEI)3.

There was also an induction for these practitioners whom had the opportunity to get to know mentor teachers, school administrators and other pre-service teachers as well as to ask questions about the school environment and philosophy. Practitioners met with mentor teachers to talk about the students, look at pictures of the school, children and special events. The idea was to present an overview of the context they were to work.

Bearing in mind the importance of contextualizing student teachers in relation to the setting where they were to carry out their practicum, FSM school provided practitioners with time to observe classes before elaborating their classroom projects.

This was done in order for the practitioners to get to know the students and the class dynamics and, through this process, be able to propose a pedagogical intervention that would suit the needs of the students and the institution. After their observations, practitioners had conferences with mentor teachers who guided and oriented their proposals. The on-site coordinator also reviewed such proposals and provided feedback when necessary.

The university assigned a schedule for student teachers in regard to school presence. Initially, however, they showed up only for the specific class without setting time aside to share with the mentor teacher or to participate in any other curricular or extra-curricular activity. Practitioners arrived with the assumption that their responsibility in the school was only to "teach the class" they had been allotted without getting involved in the school dynamics. They believed that they were required to comply only with the schedule set up for the class, but this idea gradually started to change due to the support and feedback provided by the on-site coordinator and the school dynamics that were taking place.

The PDS on-site coordinator, aiming to promote ownership by practitioners, proposed that the student teachers could work on committees which were intended to provide solutions to certain issues within the school. Practitioners were given different options so as to motivate them to work on something of their interest, thus, trying to satisfy some of the school's needs.

The areas proposed for the committees had to do with material design, evaluation techniques and instruments, an after school program, parent involvement in the school setting, cooperative work, and a PDS research group. All practitioners joined the committee which had to do with material design4.

Practitioners were given a room with appropriate conditions and materials so that they could design flashcards, lotteries, posters, etc. Every time they got together in that room they worked enthusiastically, reflecting upon their teaching practice and experiences at the school and had a good time together. In addition, the school benefited from the material they designed since it could start its own resource center. This room became a space for sharing their concerns, experiences, fears and outcomes of their practicum, which allowed them to strengthen their bonds of friendship.

Student teachers felt that the school valued their work and provided enriching teaching and learning experiences. Thus, they became more and more committed as the process continued. Mentor teachers reported the transformations practitioners went through, which was reflected in their high quality lessons. A positive response was observed from the children as well.

Thus, setting appropriate conditions for practitioners to work had an impact on their performance and their sense of belonging to the institution and the PDS.

The PDS research group, which was one of the committees proposed, was based on the belief that it is important to look for different ways to achieve the educational objectives and that an important component of that quest is to investigate; in this way, you can analyze your plan of action. As some authors claim, teaching and research as practices transform teacher educators, classroom teachers, students, institutions and educational communities in general (Clavijo, Guerrero, Torres, Ramírez, & Torres, 2004, p. 14). Nevertheless, the practitioners did not get involved on this committee.

Through the PDS project, student teachers were able to discover their potential, identify their strengths and weaknesses and receive and incorporate feedback on their teaching practicum.

This has surely been an enriching experience for practitioners, since, based on the PDS principles, practitioners have been recognized as professionals valuing their knowledge and capabilities. This fact has an impact on the construction of their professional self, empowering them as future leaders, agents of change and transformation.

Obstacles Encountered When Implementing the PDS

At this point, although there was commitment from some key parties in the PDS such as University supervisors, the PDS on-site coordinator, practitioners, mentor teachers and students, some constraints existed that we had to face, including a lack of help and support from the principal of the school. She had been working in that school for many years and it was difficult for her to accept new ideas and changes in the school. She did not speak English and the fact that the PDS had an emphasis on the teaching of English, contributed to her fear of being made redundant.

The principal used to abruptly change the school activities programmed from the beginning of the year and sometimes practitioners could not carry out the lessons they had planned. To mitigate this constraint and to get the principal more involved and committed to the PDS process, it was necessary to involve her more in the project, to show her the relevance of implementing a PDS to the benefit not only of the teaching program at the university but also of the school. She was invited to the meetings with practitioners and with mentor teachers. In addition, the constant evaluation of the process reported by students, practitioners and mentors was shared with her.

Once the principal was more knowledgeable and involved in the process, she allowed us to continue implementing the project with more freedom. Wilson (1993, p. 70) points out that

"traditionally principals have exercised control by limiting access to information in a hierarchical organization. Teachers engaged in action research, creating knowledge and collaborating directly with university faculty will be empowered. They will require a new kind of leader, one who is empowering and enabling".

This situation showed us that a transformation needs to take place in terms of beliefs and practices from people involved in a PDS.

Another constraint that we faced was the fact that there were two practitioners who started teaching at FSM school and because of personal reasons, abruptly abandoned their practicum. This situation had a negative impact on the students since they had built a close relationship with the practitioners and it was difficult for the children to understand why they had left them. That event allowed us to see that when pre-service teachers are carrying out their teaching practice, it is necessary to emphasize the importance of closing cycles appropriately, especially when working with children. Children, in this case, expected student teachers to explain the reasons behind their decision to leave, or at least to have the opportunity to say good bye; but none of this happened. Because of this situation, these student teachers failed their practicum at the university as they did not comply with its requirements.

A further constraint involved the relationship established by a student and her mentor. One student was not able to work effectively with the mentor teacher to whom she was assigned. The feedback that the mentor teacher gave was pertinent but the way she delivered it upset the student teacher in such a way that they were not able to find possible solutions and had to seek help from the on-site coordinator.

Although meetings were held to talk about difficulties in the way the mentor teacher and the practitioner were communicating and sharing their insights and experience, these encounters did not improved the situation and it was necessary to assign another mentor teacher. This situation raised awareness about the need for preparing mentor teachers to assume this fundamental role. Such preparation requires informing mentor teachers about the principles underlying the PDS, explaining the ways to implement it in the specific context, constant support and counseling, time to reflect upon the issues that may appear and exchange of ideas and analysis of specific cases that could be encountered.

In the sections above we have described the experience of this PDS in progress. We know that the parties involved are willing to continue and improve every day. There are some action plans already established to carry on with the implementation. In relation to further developments, we expect to expand the scope of the teaching practicum by involving not only student teachers of English but from other disciplines as well in order to enrich the school's curriculum. A new alliance with a private university which is sending practitioners from the Child Pedagogy Teaching Program to work with preschoolers of FSM school is being planned. Besides this additional practicum, the university is also cooperating with the school to provide training for the preschool teachers in the literacy process so that they can broaden their perspectives and understanding of the area.

Additionally, with this new partnership, workshops have been designed that will be offered to all the children, not only those of the school but of the neighborhood. These workshops are intended to help students with their reading and writing processes and with the development of artistic skills, among others. Finally, one of the plans we have foreseen for the near future is to motivate the development of action research within the partnerships.

Action research becomes vital in order to follow the PDSs' track, document what happens, reflect towards its development and look for ways to improve it every day.

Research illuminates the work and provides the necessary tools for effective processes. Cárdenas & Faustino (2003, p. 24) argue that

"more and more teachers are looking into their practice -both in their classrooms and their educational institutions to solve the problems they find or to improve their practice and their students' learning process. They are resorting to research as an informed way to lead action and change".

Conclusions

Implementing a PDS is a very appealing idea for those who are interested in improving educational experiences by means of collaborative work. There are many important aspects to bear in mind when implementing PDSs but definitely the setting in which a PDS takes place plays a key role. Alliances require, from the parties involved, identifying strengths and weaknesses, exploring different ways of working cooperatively and establishing specific roles. Having an onsite coordinator facilitates the follow-up and constant evaluation and improvement of PDSs since she set up the appropriate conditions for the practicum to take place.

The fact of having academic institutions joining forces with common goals helps in professional development and qualifications of student teachers.

In every PDS there are issues that hinder its development such as lack of support from the administrators, lack of resources and lack of understanding of participants' roles. Teitel (2003, p. 5) uses the phrase "creative tension" to describe how, in PDSs, the world of theory rubs against the world of practice. Assuming new or different roles between the parties involved when implementing a PDS requires transforming one's view's about teaching, practicum, student teachers and education in general terms; unless the concept of the PDS is embedded within the institution, the project is in danger of collapsing.

Research is a key component of PDSs since it allows for one to inquire about the teaching and learning processes, the context where it takes place, the relations held by community members and any other issue that arises from the PDS. Investigation can have multiple purposes, as part of the assessment and evaluation of the process, as a way to keep track of the implementation, as a means for constant improvement and sharing of partial or final outcomes of the experience.

As this part of our story comes to an end, we still have a long way to go yet look forward to sharing our steps forward with the educational community as we progress.

1 The terms practitioner and student teacher mean the same and thus will be used interchangeably throughout this paper.

2 Retrieved from www.fundacionparalareconciliacion.org

3 Educational Project of the Institution (Proyecto Educativo Institucional - PEI) is the name given to the compendium of mission, vision, and curriculum of any Colombian school.

4 This committee focused on designing materials for teaching purposes. It allowed student teachers to develop their creativity and to support the institution in its need to have better English teaching materials.

References

Bruner, J. (1996). The narrative construal of reality. Boston: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. L. (2003). Teacher researchers as writers: A way to sharing findings. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 49-64. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, R. & Faustino, C. (2003). Developing reflective and investigative skills in teacher preparation programs: The design and implementation of the classroom research component at the foreign language program of Universidad del Valle. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 22-24. [ Links ]

Clavijo, A., Guerrero, C., Torres, C., Ramírez, M. & Torres, E. (2004). Teachers acting critically upon the curriculum: Innovations that transform teaching. Íkala, 9(15), 11-41. [ Links ]

El Tiempo (2005). Investigadores piden adelantar políticas para fortalecer la profesión de maestro en Latinoamérica. Retrieved December 8, 2005 from El Tiempo Web site: http://eltiempo.terra.com. co/educ/not/education/ [ Links ]

Faith, K. (2004). Beginning a new partnership: Professional development school-Master of Education in Teaching style. Journal of In-service Education, 30(3), 13-25. [ Links ]

Gee, J. (1999). Introduction to discourse analysis. London: Rutledge. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. & Golembeck, P. (2002). Teachers' narrative inquiry as professional development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Jurado, F. (1999). Investigación, escritura y educación. Bogotá: Plaza y Janés. [ Links ]

Teitel, L. (2003). The professional development schools handbook. California: Corwin Press, Inc. [ Links ]

Wilson, P. (1993). Pushing the edge. In M. Milstein (Ed.) Changing the way we prepare educational leaders: The Danforth experience. Newbury Park: CA: Corwin. [ Links ]

Vélez-Rendón, G. (2003). Student or teacher: The tensions faced by a Spanish language teacher. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 7-21. [ Links ]

Viáfara, J. (2004). Student teachers' development of pedagogical knowledge through reflection. Unpublished Master's Dissertation. Universidad Distrital Francisco Jose de Caldas. Bogotá: Colombia. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K. (1983). Alternative paradigms of teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 34(3), 3-9. [ Links ]