Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile no.10 Bogotá July/Dec. 2008

Action Research on Affective Factors and Language Learning Strategies: A Pathway to Critical Reflection and Teacher and Learner Autonomy

Investigación acción sobre factores afectivos y estrategias para el aprendizaje de lengua: una ruta hacia la reflexión crítica y la autonomía del profesor y del estudiante

Yamith José Fandiño Parra*

Universidad de La Salle

* E-mail: yamithjose@gmail.com

Address: Cra 78 J Bis No. 57 B - 31 Bogotá, Colombia.

This article was received on January 30, 2008 and accepted on September 22, 2008.

This paper argues the importance of action research and critical reflection in the study of affective factors and language learning strategies in foreign language teaching. The starting point is a description of what affective factors and language learning strategies are and why Colombian EFL teachers should address these issues. Critical reflection and action research are, then, presented as rigorous and systematic activities that teachers could engage in to help their students deal with the emotional difficulties of social interaction and language learning, to open their own work to inspection and, more importantly, to construct valid accounts of their educational practices. Finally, action research is proposed as a powerful means for developing teacher and learner autonomy.

Key words: Action research, teacher and learner autonomy, critical reflection, affective factors, language learning strategies (LLS)

En este artículo se argumenta la importancia de la investigación acción y la reflexión crítica en el estudio de los factores afectivos y las estrategias de aprendizaje en la enseñanza de idiomas extranjeros. Se parte de una descripción de qué son los factores afectivos y las estrategias de aprendizaje de lengua y por qué los profesores colombianos de lengua extrajeras deberían investigar estos temas. Luego se presentan la reflexión crítica y la investigación acción como actividades sistemáticas y rigurosas que los profesores pueden emplear para ayudar a sus estudiantes a enfrentar dificultades emocionales de la interacción social y del aprendizaje de lengua, para abrir su trabajo a inspección y, más importante aún, para construir relatos válidos sobre sus prácticas educativas. Finalmente, se propone la investigación acción como un medio poderoso para desarrollar la autonomía del profesor y del estudiante.

Palabras Clave: Investigación acción, autonomía del profesor y del estudiante, reflexión crítica, factores afectivos, estrategias de aprendizaje de lengua

Introduction

In the current economic climate of our country and the growing integration of the modern world, there appears to be a considerable degree of sociocultural pressure for Colombians to become proficient at English. However, there also appear to be indications that many Colombian EFL learners do not know the relevance of beliefs, attitudes, anxieties, and motivations in language learning or the relevance of using proper use of language learning strategies (LLS). In general, EFL students seem to be unaware of the impact that certain affective and personal factors can have in their success in learning and speaking a foreign language (Rubin & Thompson, 1994). Most of them tend to have poor or limited LLS such as literal translation, rote memorization, inadequate note-taking, etc (Griffiths, 2004). Specifically, Colombian EFL students seem to lack the basic skills to start and maintain their language learning process successfully. Many students, for instance, do not display awareness of how to use a dictionary, knowledge about how to store basic vocabulary, familiarity with the use of classroom instructions, etc. (Fandiño, 2007). Noticeably, EFL students in general and Colombian EFL students in particular are not accustomed to paying attention to their own feelings and relationships in class or taking notice of their use of language learning strategies.

This article argues the importance of addressing affective factors and language learning strategies in foreign language teaching by engaging in critical reflections and carrying out action research projects.

Not only can these reflections and projects provide students with appropriate activities to face up to the emotional difficulties of social interaction and language learning, but they can also help teachers open their work to systematic inspection and construct valid accounts of their educational practices.

Affective Factors and Language Learning Strategies

The affective domain or dimension of learning has been neglected by traditional methodologies. According to Feder (1987), affective factors have habitually depended on the teacher's temperament. That is to say, considerations for beliefs, attitudes, anxieties and motivations have been incidental rather than integral to the teaching methodology and have not been grounded in a conscious philosophy of pedagogy. Affective factors should not continue being considered the Cinderella of mental functions, since they "link what is important for us to the world of people, things, and happenings" (Oatley & Jenkins, 1996, p. 122 cited in Arnold, 1999, p. 2).

Concerning affection, Caine & Caine (1991, p. 82) noted: "We do not simply learn. What we learn is influenced and organized by emotions and mindsets based on expectancy, personal biases and prejudices, degree of self-esteem, and the need for social interaction[...]". Consequently, Colombian EFL teachers need to focus on tackling problems created by negative emotions and developing more positive, facilitative mind- sets in the EFL classroom.

One effective way to work with affective factors in EFL classes is the teaching of language learning strategies (LLS). According to Oxford (1990, p. 1), language learning strategies are specific actions, behaviours, steps, or techniques that students (often intentionally) use to improve their progress in developing L2 skills and communicative ability. The past three decades have seen a growing interest in studying how language learning strategies help students acquire a second or foreign language (Stawowy, 2004). LLS theorists attribute students' success rate in language learning to the varying use of strategies. Furthermore, they believe that these strategies are teachable skills, meaning that teachers can help in the language learning process by getting students aware of strategies and encouraging their use.

Thus, Colombian EFL teachers can heighten learner awareness about affection and other relevant issues (memorization, cognition, metacognition, etc) by providing strategy training as part of the foreign language curriculum (See Appendix 1).

Affective Factors and Language Learning Strategies as Issues for Colombian EFL Teachers

The inadequate familiarity with LLS and the negligible awareness of affective factors that EFL students have are issues that Colombian EFL teachers need to address in order to aid their students in mastering English successfully; indeed, it is a tool that can assist them in satisfying certain personal, social, professional and cultural needs, wants, and goals. If Colombian EFL teachers want their students to develop their inherent potential to learn, affective factors such as anxiety, motivation, self-esteem, beliefs and attitudes can no longer be denied and the inner needs of their learners can no longer be neglected (Andres, 2002).

Similarly, they can enhance the foreign language learning process by making students aware of LLS, helping students understand good LLS, training them to develop them and, ultimately, encouraging their use (Graham, 1997; Chamot & O'Malley, 1994). As a result, affective factors and LLS are issues that Colombian EFL teachers need to reflect on, not simply items with which to improve language teaching and education in the process, but, more importantly, means to help students live more satisfying lives and be responsible members of society by exercising reflection and autonomy.

Williams & Burden (1997, p. 28) reinforce the idea of working on affective factors in language teaching when they affirm that education must focus on the learner as a developing individual making sense of and constructing meaning in his/ her own world. In their model, the learner is an individual with affective needs and reactions which must be considered as an integral part of learning, as also must the particular life contexts of those who are involved in the teaching-learning process. Tooman (2006) concurs with these authors when she states that stimulating the affective dimension of learning is vital for (adult) education because learners become bored and may abdicate from sustained learning endeavors without the emotive stimuli in the affective dimension. To Tooman, educators must deal with the whole person in and out of the classroom if they want to succeed in their efforts to facilitate human growth and development and the integration of the person's mind, body, spirit, emotions, relationships, and socio-cultural context.

The work on affective factors has been greatly supported by humanism. Wang (2005) explains that humanism emphasizes the importance of the inner world of the human being and places the individual's thoughts, feelings and emotions at the forefront of all human developments. Affect is not one of the basic needs of human beings, but the condition and premise of the other physical and psychological activities. To Wang, educators should focus their efforts on the development of human values, the growth in self-awareness and in the understanding of others, the sensitivity to human feelings and emotions and the active student involvement in learning and in the way learning takes place. With regard to humanism, Stevick claims that "in a language course, success depends less on materials, techniques and linguistic analyses, and more on what goes on inside and between the people in the classroom" (1980, p. 4).

Attention to affective factors and interest in humanism show not only a desire (on the part of researchers and practitioners) to examine and adopt ideas from other disciplines (e.g. psychology, sociology and philosophy), but also an awareness of the expanding role of EFL/ESL as a vehicle of education and of "learning" per se. As an educational endeavor, EFL/ESL should aim at enabling people, without exception, to develop all their talents to the full and to realize their creative potential, including responsibility for their own lives and achievement of their personal goals. In this light, Delors et al. (1996) maintain that educators should help students learn throughout life, which consists of helping students learn to know, learn to do, learn to live together and learn to be. Accordingly, EFL/ESL should teach students to learn to learn in order to allow them to achieve their full potential as citizens of the world.

In simple terms, ESL/EFL teachers need to contribute to every student's complete development - mind and body, intelligence, sensitivity, aesthetic appreciation and spirituality.

This new role of EFL/ESL, helping students learn throughout life, involves a broader understanding of what language teaching means and entails. Language teaching should not simply be understood as a methodical effort to develop students' communicative competence but as an educational commitment to helping students learn to learn throughout life.

That is to say, language teaching should help students acquire the skills, knowledge, attitudes and strategies they need in order to interact with their learning in an informed and self-directed manner. In sum, language teachers should not only strive to help students become good language users, but also should help students become successful learners and fulfilled individuals.

This broader understanding of ESL/EFL, ESL/EFL as an educational commitment to learning throughout life, calls for critical and systematic reflection from ESL/EFL teachers. Thinking over their experiences as educators can allow ESL/EFL teachers to review critically their roles, challenges and responsibilities, which ultimately can open up space for transformation and improvement (See discussion on critical reflection below). However, Colombian EFL teachers should not simply reflect to provide their students with appropriate activities, materials and methods to understand and face up to the emotional, personal and sociocultural demands of foreign language learning. Their reflections must go beyond merely achieving instructional aims. Colombian EFL teachers should strive to observe, question and understand the teaching settings in which they work and the teaching practices they follow. In other words, teachers' reflections should be directed toward bringing to light the implicit rationale behind things done in class and at examining the beliefs and values that form or shape actions in class. This way, Colombian EFL teachers can not only focus on the learner as an individual with affective needs and reactions that must be considered integral to language learning, but can also open their own work to critical inspection and to construct valid accounts of their educational language practices.

Critical Reflection

In the last 30 years, several authors have assumed that teachers are researchers who should permanently submit their daily practice to rigorous self-examination to overcome their repetitive routine by continuously reflecting on and transforming their practices (See Stenhouse, 1993; Elliot, 1994; McKernan, 1996; Kemmis, 1998, etc.).

Educational research should aim to explain what actually happens inside the classroom, the direct and indirect influence of internal and external factors related to the student, the teacher and the ELT curriculum (Van Lier, 1988). At the heart of teachers' educational research, there should be a focus on critically inquiring into their own practice. In other words, teachers should use educational research to think about their own contexts, to analyze their judgments and interpretations and to distance themselves to make the basis of their work open to inspection.

One critical way to open teachers' work to inspection is what Donald Schön called practice-as-inquiry. This inquiry occurs when the practitioner reflects both while engaged in action and, subsequently, on the action itself as an attempt to make his or her own understanding problematic to him or herself. The teacher-researcher strives to test his or her constructions of the situation by bringing to the surface, juxtaposing, and discriminating alternate accounts of reality.

The point is to see the taken-for-granted with new eyes, to be able to come out of this experience with an expanded appreciation of the complexity of learning, of teaching, and of a stronger sense of how external realities affect what the teacher-researcher can (wants to) really do (Schön, 1983).

Another proponent of practice-asinquiry is Whitehead. He regards it as a way to construct a living educational theory from practitioner's questions of the kind: How do I improve my practice?

Valid accounts of a teacher's educational development, explains Whitehead, should be accepted when teachers ask themselves how to improve their practices, undertake to improve some aspect of their practice, reflect systematically on such a process and provide insights into the nature of their descriptions and explanations. With this standpoint, Whitehead does not deny the importance of propositional forms of understanding. Instead, he argues for a reconstruction of educational theory into a living form of question and answer which includes propositional contributions from the traditional disciplines of education (Whitehead, 1988).

In a similar vein, Restrepo (2000) explains that teachers, in fact, do research when they submit their daily practice to rigorous self-examination to face and transform their everyday practices in ways that respond adequately to their working environment, the needs of their students and their sociocultural agenda. To him, teachers as educational practitioners can use retrospection, introspection and participative observation to clarify guiding theories and to specify pedagogical interventions in order to re-signify and transform unsuccessful practices. He argues that, if done systematically and consistently, the empirical doing of teachers can become a reflective doing, a reflective practice. This "pedagogical knowhow" can allow teachers both to overcome their repetitive routine and to objectify their practices, which can ultimately help them reflect on and transform their practices simultaneously.

Cárdenas & Faustino (2003) discuss the importance of critical reflection and research when they show the necessity of preparing students and future teachers to possess not only linguistic competence in the foreign languages, but also competences that allow them to reflect, analyze and find ways of improving their professional practice. To them, more and more Colombian EFL teachers are looking into their practice -both in their classrooms and their educational institutions- to solve the problems they find or to improve their practice and their students' learning processes. They are resorting to research as an informed way to lead action and change. Similarly, González & Sierra (2005) assert that Colombian EFL teacher educators rely on six main alternatives to face the challenges in their professional growth.

Among these alternatives for professional development, doing research is regarded as the most important academic activity in order to maintain the standards set by the profession since it is the bridge between reality and change. Systematic reflection on practice is another significant alternative Colombian EFL teacher educators have to enhance their professional development. According to González & Sierra, teacher educators report learning from their own successes and failures and becoming better teachers after confronting their ideal views and experiences.

Cárdenas (2002, 2004) shows that critical reflection in research has a series of positive effects for the Colombian EFL field. Teachers become more active and interested in keeping an inquiring attitude in order to give meaning to their daily work. They look for connections between theories and practice and become more accurate and analytical observers. They also work cooperatively with students and colleagues to systematically construct personal and workable theories. To Cárdenas, critical reflection and research empower Colombian EFL teachers because these allow them to become agents of change committed to developing a pedagogically grounded understanding of their areas of concern, their working conditions and their everyday practices. Critical reflection is, then, a necessary condition for teachers to understand the underlying principles of their practices and to open up space for professional and personal transformation.

Action Research

As stated before, Colombian EFL teachers should not simply aim at doing research to create new or improved activities, practices and principles; they should do research to bring to light the rationale behind those activities, practices and principles. In particular, research should allow teachers to engage in critical reflection about their set of beliefs or expectations about what language learning is, how a foreign language is learned and why certain practices or activities are acceptable or not in a foreign language classroom. Evidently, the integration between teaching, researching and learning requires a type of research that proffers reflection and self-examination to teachers and students. This integration also requires a type of research in which teachers can search for solutions to everyday, real problems experienced in classrooms, or look for ways to improve instruction and increase student achievement. Based on these requirements, Colombian EFL studies can use action research (AR) to provide for a type of research in which teaching, learning, reflection and self-actualization can take place in the classroom. Rightly, Parrot (1996, p. 3) defined AR as follows:

[…]not so much something that we do in addition to our teaching but as something that we integrate into it. In many ways it is a state of mind - it is skepticism about assumptions and a willingness to put everything to the test[…]

It is a way of ensuring that we continue to learn even as we teach. It helps stave off staleness and routine.

According to McNiff (2002), AR is a term which refers to a practical way of looking at one's own work in order to check that it is as one would like it to be. Because AR is done by oneself, the practitioner, it is often referred to as practitioner based research, because it involves one's thinking about and reflecting on one's work, it can also be called a form of self-reflective practice. The idea of self reflection is central because action researchers enquire into their own practices.

To McNiff, AR is an enquiry conducted by the self into the self. One, as a practitioner, think about one's own life and work, and this involves asking oneself why one does the things that one does, and why one is the way one is. As concerns McNiff 's point of view, when one produces one's research report, it shows how one has carried out a systematic investigation into one's own behaviour, and the reasons for that behaviour. The report shows the process one has gone through in order to achieve a better understanding of oneself, so that one can continue developing oneself and one's work.

Different scholars have discussed AR. In 1986, Carr & Kemmis stated that AR was a form of self-reflective enquiry that participants in social situations undertook in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own practices and the situations in which these practices were carried out. In 1988, Kemmis & McTaggart defined AR as a combination of the terms "action" and "research" because it puts ideas into practice for the purpose of selfimprovement and increases knowledge about curriculum, teaching, and learning.

To them, the ultimate result of AR is improvement in what happens in the classroom and school. More recently, McKernan (1996) explained that AR was systematic self-reflective inquiry by practitioners to improve practice. In McKernan's opinion, AR is the reflective process whereby in a given problem area in which one wishes to improve practice or personal understanding, critical and systematic inquiry is carried out by oneself, the practitioner.

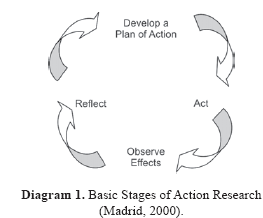

A variety of procedural plans has been proposed by different scholars regardless of how AR is understood and why it is promoted. All adopt methodical and interactive sequences of research. These sequences are meant to offer a systematic approach to introducing innovations in teaching and learning. They seek to do this by putting the teacher in the role of producer of educational theory and user of this theory. The process of researching in AR brings theory and practice together. According to Madrid (2000, p. 22), there are four classic developmental phases of AR, to wit:

- Phase 1: Develop a plan of action to a) improve what is already happening or b) identify and examine a "puzzle" or problem area in your teaching;

- Phase 2: Act to implement the plan;

- Phase 3: Observe the effects of action in the context in which it occurs, and

- Phase 4: Reflect on these effects.

These stages are shown in the following diagram:

Cárdenas (2000, 2006) states that AR is a form of self-inquiry leading to the interpretation and improvement of teachers' teaching practices as well as to understanding the situations where they take place. AR is an alternative that centres teachers' reflection on their educational contexts and allows for the discovery of new disciplinary knowledge. To Cárdenas, AR enhances feelings of responsibility, ownership and confidence because teachers can evaluate received knowledge and suggested innovations in light of their school life. Based on the previous theoretical considerations, AR can be regarded as a reflective activity dealing with issues arising from the formative quality of the curricular experiences and about the pedagogical conditions that make them possible.

Reports based on AR can be found in Colombian journals. In 2005, Ríos & Valcárcel used AR in their effort to show how English language learning can be developed from reading processes involving the other language skills and can help students to develop individual and social skills. They found AR to be an effective means to confront common problems including people who are involved in those problems. Forero (2005) decided to use steps of the AR model proposed by Burns (1999) in a research project carried out in order to implement task-based learning with a group of 50 seventh graders to improve oral interaction. AR was also used by Ariza (2005) in her research study involving the use of a series of activities related to the generation of ideas and the focus on stages from the process writing approach. These are just a few samples of works done by Colombian EFL teachers who have used AR in their personal efforts to enhance understanding and improve their educational contexts.

When using AR to transform their educational contexts, teachers can be learners interested in studying the curricular and pedagogical considerations surrounding their practices and, at the same time, researchers who regard their practices as provisional and unsatisfactory and who use research to achieve changes that are educationally worthy. Additionally, students can become active agents in their learning process; agents who take charge of their learning process by generating ideas and availing themselves of learning opportunities, rather than simply reacting to various stimuli of the teacher. In brief, AR can be regarded as an effective way to promote teacher and learner autonomy as a result of new and better pedagogical and methodological opportunities (See further discussion).

Teacher Autonomy

Apart from systematization, documentation, understanding and knowledge, AR provides teachers with autonomy. Here, I do not understand autonomy as a generalized "right to freedom from control" (Benson, 2000) or as "a teacher's capacity to engage in self-directed teaching" (Little, 1995), but as a capacity for self-directed teacher-learning (Smith, 2000).

Smith explained that the idea education should embrace teacher autonomy is not at heart a new proposition (advocates of teacher development, teacher-research, classroom-research and so on would appear to share this goal implicitly) (2000, p. 95).

What might be a relatively new idea is the emphasis on the development of autonomy through reflective teacher-learning. This autonomy must be understood as a critical reflection that teachers do on when, where, how and from what sources they (should) learn. This type of autonomy mainly takes place when teachers monitor the extent to which they constrain or scaffold students' thinking and behavior, when they reflect on their own role in the classroom, when they attempt to understand and advise students, and, ultimately, when they engage in investigative activities.

Actual engagement in and concern with reflective teacher-learning appear, then, to be a powerful means for developing teacher autonomy, particularly when it is explicitly linked to action research. Reflective teacherlearning and AR are essential for teachers to construct autonomy. This autonomy takes place when teachers gain better abilities and a greater willingness to learn for themselves. It emerges when teachers develop an appropriate expertise of their own. The point I am trying to make here is that Colombian EFL teachers can become autonomous if they use AR and reflective teacher-learning as a methodology to develop a capacity to inspect their own work, to validate their educational development and, ultimately, to foster learner autonomy.

Usma (2007) explains that research on professional development as a means for teacher autonomy has revealed the positive effects that action research and study groups, among other alternatives of development, have on teachers' knowledge, attitudes, and actions depending on the content and process of these types of endeavors. Based on his comprehensive literature review, Usma confirms the positive effects that teacher-directed research, continuous connection between theory and practice, practical workshops, discussions, continuous feedback, critical reflection, and conducting and reporting teacher research have on teachers' engagement with professional development and exercise of autonomy. To him, effective professional development experiences allow participants to increase their awareness of innovative practices, improve their attitudes towards the teaching-learning process, use their power to generate change in their schools and, ultimately, exercise control over teaching and assessment, curriculum development, school functioning, or professional development matters.

Pineda & Frodden (2008) state that making part of a collaborative action research project can transform an EFL teacher from a thoughtful person into a reflective professional because he/she gets involved in continuous cycles to plan, carry out and evaluate actions, which helps him/ her to gain awareness of their teacher's role and to renew their engagement with the profession. The authors explain that collaborative dialogue with colleagues or research groups is a major influence on teachers' professional development since it helps them enhance their critical thinking, take into account the multiple contextual factors that a teacher needs to consider when making decisions, and reminds them of the social responsibility we have to improve our educational contexts. The authors claim that doing action research can be viewed as a means to be better prepared for the challenges we encounter in our profession, which ultimately give us space and opportunities to self-direct their professional learning and development.

To sum up, AR can be the basis for Colombian EFL teachers' autonomy. First of all, AR is a feasible effective form of selfinquiry to interpret and improve teaching practices and educational contexts. Many EFL teachers have demonstrated that as teacher-researchers they can reflect about what successful foreign language teaching involves and how effective practices can be approached in foreign language classrooms. Their AR studies have not only contributed to the expansion of knowledge, but have also opened space for study groups. Definitely, AR can and has helped Colombian EFL teachers develop their own expertise.

Learner Autonomy

Cast in a new perspective and regarded as understanding the purpose of their learning programme, explicitly accepting responsibility for their learning, learners, autonomous learners, that is, are expected to reflect critically on and take charge of their own learning (Little, 1995). For all intents and purposes, the autonomous learner takes a (pro-) active role in the learning process, generating ideas and availing him- or herself of learning opportunities, rather than simply reacting to various stimuli of the teacher. In other words, the autonomous learner is a selfactivated maker of meaning, an active agent in his own learning process. The learner is not one to whom things merely happen; the learner is the one who, by his own volition, causes things to happen (Rathbone, 1971, p. 100 cited in Candy, 1991, p. 271).

However, learner autonomy does not mean that the teacher becomes redundant; abdicating his/her control over what is transpiring in the language learning process. Instead, learner autonomy involves a dynamic process learned at least partly through educational experiences and interventions (Candy, 1991, cited in Thanasoulas, 2000, p. 115). What permeates this article is the belief that in order to help learners to assume greater control over their own learning, it is important that Colombian EFL teachers help them to become aware of and identify the strategies that they already use or could potentially use. In other words, autonomous learning is by no means teacherless learning. As Sheerin (1997, cited in Benson & Voller, 1997, p. 63) succinctly put it, "[…]Teachers have a crucial role to play in launching learners into self-access and in lending them a regular helping hand to stay afloat". Thus, the teacher's role is to create and maintain a learning environment in which learners can be autonomous in order to become more autonomous.

Learner autonomy can, then, be promoted through AR studies on language learning strategies because, as Thanasoulas (2000) explained, learner autonomy mainly consists of becoming aware of and identifying one's strategies, needs and goals as a learner and having the opportunity to reconsider and refashion approaches and procedures for optimal learning. AR studies on language learning strategies can do just that. They can help students become aware of and familiar with thoughts, behaviors, mental steps or operations to learn a new language and to regulate their efforts to do so. They can also encourage them to assume greater responsibility for their own language learning and help them assume control over their own learning process.

Luna & Sánchez (2005) explain that the classroom is one of the fundamental areas for gaining autonomy in the context of Colombian EFL learning. They explain that the promotion and education of people about autonomous learning implies a pedagogic approach which focuses on specific socio-cultural needs in and out of the classroom. That is to say, pedagogic innovations which guide the participants -both students and teachers- to discover their needs and individual learning styles, to tackle new learning strategies and to enhance cognitive, social and reflective processes required in the learning of a new language. To them, the use of learning strategies from the start of the learning process helps learners to be directors of their own learning, to plan, monitor and evaluate their learning tasks, which leaves room for self-regulation and the transfer of knowledge, skills and actions from the classroom to new social and cultural areas.

Similarly, Habte-Gabr's (2006) research with university students in Bogotá showed that language learning strategies in general and socioaffective language learning strategies in particular should be considered central to studying EFL because, as he noticed in his study, students in Colombia tend to seek a mentorship relationship with their teachers and tend to learn more when they are able to share aspects of their personal life and form strong bonds.

He regarded socio-affective strategies as tactics to stimulate learning through establishing a level of empathy between the instructor and student. According to him, the enhancement of socio-affective strategies permits the student to eventually learn how to see the instructor as a resource for acquiring language and content and to assume greater responsibility for their own language learning at the same time that they are provided with options to obtain humane support.

As can be seen, critical reflection and action research studies on language learning strategies and affective factors can launch students into generating new or improved behaviors and ideas in their learning process and into availing themselves of learning opportunities, which ultimately brings about their own autonomy.

Conclusion

Colombian EFL teachers should address issues of affective factors and language learning strategies by engaging in critical reflection and carrying out action research projects. Not only can these reflections and projects provide their students with appropriate activities to face up to the emotional difficulties of social interaction and language learning, but they can also open their own work to systematic inspection and construct valid accounts of their educational practices.

Critical reflection in general and AR in particular appear to be powerful means for developing both teacher autonomy and learner autonomy. On the one hand, critical reflection and AR projects can develop teacher autonomy because new methodological and pedagogical opportunities are opened up for teachers to develop an appropriate expertise of their own. On the other hand, learner autonomy is developed because students can become aware of and identify their strategies, needs and goals as learners in order to reconsider and refashion approaches and procedures for optimal language learning. In the end, action research studies on language learning strategies can help Colombian EFL teachers and students realize that they can and should be active, reflective and autonomous agents of their language teaching and learning processes.

References

Andres, V. (2002, March). The influence of affective variables on EFL/ESL learning and teaching. In The Journal of the Imagination in Language Learning and Teaching, 7. Retrieved August 20, 2006 from JILLT Web site: http://www.njcu.edu/CILL/vol7/andres.html [ Links ]

Ariza, A. V. (2005). The process-writing approach: An alternative to guide the students' compositions. PROFILE, 6, 37-46. [ Links ]

Arnold, J. (ed). (1999). Affect in language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Benson, P. (2000). Autonomy as a learners and teacher's right. In Sinclair, B., McGrath, I. & Lamb, T (Eds.), Learner autonomy, teacher autonomy: New directions (pp. 111-117). London: Addison Wesley Longman. [ Links ]

Benson, P. & Voller, P. (1997). Autonomy and independence in language learning. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Caine, R. N. & Caine, G. (1991). Making Connections: Teaching and the human brain. Menlo Park, CA: Addison Wesley. [ Links ]

Candy, P. (1991). Self-direction for lifelong learning. California: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Chamot, A .U. &. O'Malley, J. M. (1994). The CALLA handbook: Implementing the cognitive academic language learning approach. White Plains, NY: Addison Wesley Longman. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. L. (2000). Action research by English teachers: An option to make classroom research possible. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 2(1), 15-26. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. L. (2002). Teacher research as a means to create teachers' communities in inservice programs. HOW. A Colombian Journal for English Teachers, 9, 1-6. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. L. (2004). Classroom research by inservice teachers: Which characteristics? Which concerns? Research News, 3-7. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. L. (2006). Orientaciones metodológicas para la investigación-acción en el aula. Lenguaje, 34, 187-216. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, R. & Faustino, C. C. (2003). Developing reflective and investigative skills in teacher preparation programs: The design and implementation of the classroom research component at the foreign language program of Universidad del Valle. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 22-48. Retrieved July 10, 2008 from CALJ Web site: http://calj.udistrital.edu.co/pdf_files/App_2003/Art2.pdf [ Links ]

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge, and action research. Lewes, Sussex: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Delors, J. (Coord.) (1996). La educación encierra un tesoro. Informe a la UNESCO de la Comisión Internacional sobre la educación para el siglo XXI. Madrid: Santillana. Ediciones [ Links ]

Elliot, J. (1994). La investigación acción en educación. Madrid: Ediciones Morata. [ Links ]

Fandiño, Y.J. (2007). The explicit teaching of socioaffective language learning strategies to beginner EFL students at the Centro Colombo Americano: An action research study. Bogota: Master's thesis. Division of advanced education, University of La Salle, Colombia. [ Links ]

Feder, M. (1987). A skills building game for the ESL classroom. In DiscoveryTrailTM. Originally submitted to the School for International Training, Brattleboro, VT. Retrieved August, 2006 from DiscoveryTrailTM Web site:http://www.eslus.com/discovery/thesis.htm [ Links ]

Forero, Y. (2005). Promoting oral interaction in large groups through task-based learning. PROFILE, 6, 73-81. [ Links ]

Graham, S. (1997). Effective language learning. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Griffiths, C. (2004, February). Language learning strategies: Theory and research. In School of foundations studies, Occasional paper, 1. AIS St Helens, Auckland: New Zealand. Retrieved August 20, 2006 from Web site: http://www.crie.org.nz/research_paper/c_griffiths_op1.pdf [ Links ]

González, A. & Sierra, N. (2005). The professional development of foreign language teacher educators: Another challenge for professional communities. Ikala, Revista de lenguage y cultura, 10(16), 11-39. Retrieved July 20, 2008 from Íkala Web site: http://quimbaya.udea.edu.co/ikala/index.php?option=com_contenttask=viewid =333Itemid=102 [ Links ]

Habte-Gabr, E. The importance of socio-affective strategies in using EFL for teaching mainstream subjects. Humanising English Teaching, 8(5), (Sept. 2006). Retrieved August 20, 2006 from Web site: http://www.hltmag.co.uk/sep06/sart02.htm [ Links ]

Kemmis, S. (1998). El currículo más allá de la teoría de la reproducción. Madrid: Ediciones Morata. [ Links ]

Kemmis, S. & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research planner. (3rd edition). Australia: Deakin University Press. [ Links ]

Little, D. (1995). Learning as dialogue: The dependence of learner autonomy on teacher autonomy. System, 23(2), 175-181. [ Links ]

Luna, M. & Sánchez, D. K. (2005). Profiles of autonomy in the field of foreign languages. PROFILE, 6, 133-140. [ Links ]

Madrid, D. (2000). Observation and research in the classroom. Teaching English as a Foreign Language, 1-100. [ Links ]

McKernan, J. (1996). Curriculum action research. A handbook of methods and resources for the reflective practitioner (2nd ed.). London: Kogan. [ Links ]

McNiff, J. (2002). Action research for professional development: Concise advice for new action researchers. Jean McNiff, booklet 1(6). Retrieved August 20, 2006 fromhttp://www.jeanmcniff.com/booklet1.html#6 [ Links ]

Oatley, K. & Jenkis, J. (1996). Understanding Emotions. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Oxford, R. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. New York: Newbury House. [ Links ]

Parrot, M. (1996). Tasks for language teachers: A resource book for training and development. UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Pineda, D. & Frodden, C. (2008). The development of a novice teacher's autonomy in the context of EFL in Colombia. PROFILE, 9, 143-162. [ Links ]

Rathbone, C. H. (1971). Open Education: The Informal Classroom. New York: Citation Press. [ Links ]

Restrepo, B. (2000). Maestro investigador, Escuela investigadora e Investigación. Cuadernos Pedagógicos, 14, 97-106. [ Links ]

Ríos, S. R. & Valcárcel, A. M. (2005). Reading: A meaningful way to promote learning English in high school. PROFILE 6, 37-46. [ Links ]

Rubin, J. & Thompson, I. (1994). How to be a more successful language learner (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle. [ Links ]

Sheerin, S. (1997). An exploration of the relationship between self-access and independent learning. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 54-65). London: Longman. [ Links ]

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic books. [ Links ]

Smith, R. (2000). Starting with ourselves: Teacherlearner autonomy in language learning. In B. Sinclair, I. McGrath, & T. Lamb, (Eds.), Learner autonomy, teacher autonomy: New directions (pp. 89-99). London: Addison Wesley Longman. Retrieved August 20, 2007 from Web site: http://www.warwick.ac.uk/elsdr/Teacher_autonomy.pdf [ Links ]

Stenhouse, L. (1993). La investigación como base de la enseñanza. Madrid: Ediciones Morata. [ Links ]

Stevick, E. (1980). Teaching language: A way and ways. Rowley, Mass: Newbury House. [ Links ]

Stawowy D. M. (2004). Learning strategies in the secondary foreign language classroom: An essential curriculum component for beginning students. Master's Project in Curriculum and Instruction. The College of William and Mary: School of Education. Retrieved July 10, 2006 from Web site: http://web.wm.edu/education/599/04projects/Diaz.pdf?=svr=www [ Links ]

Thanasoulas, D. (2000, November). What is learner autonomy and how it can be fostered? The Internet TESL journal, 6(11). Retrieved July 17, 2007 from Web site: http://iteslj.org/Articles/Thanasoulas-Autonomy.html [ Links ]

Tooman, T. (2006). Affective Learning: Activities to promote values comprehension. Soultice Training. Retrieved August 20, 2008 from Web site: http://www.soulsticetraining.com/commentary/affective.html [ Links ]

Usma, J. (2007). Teacher autonomy: A critical review of the research and concept beyond applied linguistics. IKALA Revista del lenguage y cultura, 12(18), 245-275. Retrieved July 20, 2008 from Íkala Web site: http://quimbaya.udea.edu.co/ikala/index.php?option=com_contenttask=vie wid=333Itemid=102 [ Links ]

Van Lier, L. (1988). The classroom and the language learner. Ethnography and second language classroom research. Harlow: Longman. [ Links ]

Wang, G. (2005). Humanistic approach and affective factors in foreign language teaching. Sino-US English Teaching, 2(5), 1-5. Retrieved August 10, 2006 from http://www.linguist.org.cn/doc/su200505/su20050501.pdf [ Links ]

Whitehead, J. (1988). Creating a living educational theory from questions of the kind, How do I improve my practice? Cambridge Journal of Education, 19(1), 41-52. Retrieved August 20, 2006 from Web site:http://www.bath.ac.uk/Eedsajw/writings/livtheory.html [ Links ]

Williams, M. & Burden, R. L. (1997). Psychology for language teachers: A social constructivist approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]