Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.11 no.2 Bogotá July/Dec. 2009

Exploring Teachers Practices for Assessing Reading

Comprehension Abilities in English as a Foreign Language

Exploración de las prácticas de los profesores para evaluar las habilidades de

comprensión lectora en inglés como lengua extranjera

Jorge Hugo Muñoz Marín

Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia

hugomu74@gmail.com

Address: Universidad de Antioquia, Escuela de Idiomas, Calle 67 No. 53-108 - bloque 11. Medellín - Antioquia, Colombia.

This article was received on November 19, 2008 and accepted on August 20, 2009. This paper reports the findings of an exploratory study that aimed at identifying the assessment practices that English teachers have in the reading comprehension program at Universidad de Antioquia. Data collection included documentary analysis and interviews of 15 teachers and of the head of the program. Findings suggest diverse practices in assessing reading comprehension, the use of quantitative instruments to evaluate qualitatively, students' lack of familiarity with qualitative assessment practices, teachers' lack of familiarity with alternative assessment and teachers' concern for verification of achievement of learning objectives. Conclusions highlight the need to expand the teachers' assessment repertoire through in-service programs designed for the specificity of teaching reading comprehension skills. Key words: Foreign language reading, reading abilities, reading comprehension, assessment criteria, teachers' assessment practices Este artículo reporta los hallazgos de un estudio exploratorio que buscó identificar las prácticas evaluativas de los profesores de inglés en el programa de comprensión lectora de la Universidad de Antioquia. La recolección de datos incluyó un análisis documental y entrevistas con 15 profesores y el coordinador del programa. Los hallazgos sugieren prácticas diversas en la evaluación de la comprensión lectora, el uso de instrumentos cuantitativos para evaluar cualitativamente, la falta de familiaridad de los estudiantes con las prácticas de evaluación cualitativa, la falta de familiaridad de los profesores con la evaluación alternativa y la preocupación de los profesores por verificar el cumplimiento de los objetivos de aprendizaje. Las conclusiones señalan la necesidad de expandir el repertorio evaluativo de los profesores por medio de programas de desarrollo profesional centrados en la enseñanza de habilidades en la comprensión lectora. Palabras clave: Percepciones de los docentes sobre la evaluación en el aula, uso de evaluaciones, formación en evaluación Introduction This paper starts by introducing a literature review to frame key issues in the study. Then, it will describe the context of the study, data collection and data analysis. The main findings are discussed and supported with excerpts from participants' testimonies. Finally, I will state some conclusions. Colombian universities have experienced an increasing number of programs that promote the acquisition of reading skills in undergraduate curricula. These programs intend to provide students with the necessary skills to access information in English that is pertinent for understanding scientific literature in their fields of training as well as non academic texts. The Universidad de Antioquia requires the acquisition of reading skills in a foreign language in all its undergraduate and graduate programs. To fulfill the requirement, the School of Languages offers reading comprehension courses taught according to some general guidelines that some professors have constructed collaboratively. In my experience as a professor in the program for the last 4 years, I have faced the challenge of assessing the reading comprehension skills of my own students. Some other colleagues have shared my concerns. In an attempt to improve my teaching practice and contribute to the academic growth of the program, I became motivated to explore in more detail the current assessment practices that English teachers have in our program. I hope that the study reported in this paper will contribute to the consolidation of better approaches in the development of reading comprehension skills in our context.

Literature Review

In this section, I will present some theoretical points related to reading comprehension and its assessment in a foreign language to frame the study.

To start analyzing the assessment practices of EFL teachers in a reading comprehension program, I will present a definition of reading. Dubin & Bycina (1991) explain reading as a selective process taking place between the reader and the text, in which background knowledge and various types of language knowledge interact with information in the text to contribute to text comprehension. Grabe & Stoller (2002, p. 17) view reading as "the ability to understand information in a text and interpret it appropriately". The authors state that this definition does not account for the true nature of reading abilities because it does not consider four main issues: One, the ways to engage in reading; two, it does not define fluent reading abilities; it does not explain reading as a cognitive process that takes place under intense time constraints; and four, it does not explain how reading varies according to one's ability in the second language. Alyousef (2005) states that reading is an "interactive" process that takes place between a reader and a text and that leads to automaticity (reading fluency). In this process, the reader interacts dynamically with the text as he/she tries to elicit the meaning. Additionally, various kinds of knowledge are used: linguistic or systemic knowledge as well as schematic knowledge.

Consistent with the definitions presented above, research on reading comprehension focused on describing the processes to understand reading. This is how Alyousef (2005) identified six general skills and knowledge areas necessary for reading comprehension, namely: automatic recognition skills, vocabulary and structural knowledge, formal discourse structure knowledge, content/world background knowledge, synthesis and evaluation skills/strategies and metacognitive knowledge and skills monitoring. Additionally, Grabe & Stoller (2002) identify different components and knowledge areas in the process of reading. They classify them as two different processes for skilled readers: lower- level processes, which are related to vocabulary and grammar recognition when reading; and higher level processes, which are concerned with comprehension, schemata and interpretation of a text. According to these authors, a fluent reader may need the combination of lower and higher level processes; otherwise, their reading skills may not be as efficient and reliable as they should be. These definitions and considerations have provided the guidelines and principles for establishing the competences a successful foreign language reader should have.

In my experience as a teacher of reading comprehension in EFL, I find that Grabe & Stoller (2002) provide a complete and accessible theory of reading. I believe that their description of the lower and higher reading processes allows us to construct a better understanding of reading, and therefore, an informed approach to teaching reading comprehension.

The appropriate use of the reading processes presented above determines if a reader is successful or not. Several authors define the conditions for success in reading. Block (1986) finds that more successful readers use general strategies such as anticipating content, recognizing text structure, identifying main ideas, using background knowledge, monitoring comprehension, and reacting to the text as a whole. Less successful readers rely on local strategies such as questioning the meaning of individual words and sentences, seldom integrating background knowledge with the text, and not focusing on main ideas. Singhal (2001) concludes that successful readers tend to use cognitive, memory, metacognitive, and compensation strategies far more than less proficient readers. Less successful readers generally focus on local concerns such as grammatical structure, sound-letter correspondence, word meaning, and text details. Finally, Saricoban (2002) examines the use of strategy of post-secondary ESL students and finds that the successful readers engaged in predicting and guessing activities, made use of their background knowledge related to the text's topic, guessed the meaning of unknown words, and skimmed and scanned the text. Less successful readers focused on individual words, verbs in particular. Brown (2004) calls an efficient reader, the one who is able to master fundamental bottom-up and top down strategies; as well as an appropriate contents and formal schemata.

The identification of successful and not successful readers is regularly a task that teachers develop in the classroom through assessment practices. In the case of foreign language reading, assessment should aim at collecting information from students' reading abilities, and then using that information for planning and implementing better reading classes (Gersten, 1999). In that sense, teaching reading comprehension and assessing it should go hand and hand. Similarly, Aweiss (1993) states that assessment is a necessary component of effective instruction as it should help teachers answer many questions about students' learning and, therefore, make it possible to prepare and implement more effective teaching. Foreign language reading assessment should focus on the idea of identifying readers in the classroom so that those called "non-proficient" can receive more attention in order to improve and those called "proficient" can enhance their abilities. According to Cross & Paris (1987), reading comprehension assessment should be implemented based on three specific purposes. The first one is sorting, used to predict a learner's academic success or to indicate mastery of an instructional program. The second one is diagnosing, intended to gather information from learners' strategies and processes so that the teacher can make decisions about the instruction process. The final goal is evaluation, which calls for determining the effect of a program on a specific community. I agree with these ideas because assessment certainly informs teaching and this belief motivated me to explore the assessment practices in our reading comprehension program.

Grabe & Stoller (2002) state how the major goal of foreign language reading assessment should be to introduce assessment practices that incorporate the following: fluency and reading speed, automaticity and rapid word recognition, search processes, vocabulary knowledge, morphological knowledge, syntactic knowledge, text structure awareness and discourse organization, main ideas comprehension, recall of relevant details, inferences about text information, strategic processing abilities, summarization, synthesis skills and evaluation and lastly, critical reading. The authors explain that assessment tasks should be based on real world reading needs and activities.

Teachers implement the assessment practices described above using specific assessment instruments. According to Aweiss (1993), assessment instruments range from the unstructured and spontaneous gathering of information during instruction to structured tests with specifically defined outcomes and directions for administration and scoring. Aebersold & Field (1997) recognize some forms of assessment as informal, alternative, developmental, learning-based, and studentcentered. Others are considered formal, teacher controlled, traditional, and standardized methods. These assessment forms range from small forms, such as a quiz to recall information or an exercise at the end of the reading, to much larger forms, such as a presentation of a project or a unit examination that measures learning throughout an entire course. In a study of assessment instruments used for foreign language teaching, Frodden, Restrepo & Maturana (2004) classified assessment instruments as hard and soft. Hard assessment instruments are a traditional way to assess that emphasizes objectivity, precision, and reliability focusing on product rather than process. Soft assessment instruments, on the other hand, deal with a naturalistic, alternative and purposeful ways of assessment. Alderson (2000) classifies new and old trends for assessing reading, but explicitly asks for the need to dedicate extra thought to how informal assessment can replace more formal testing, so that informal assessment procedures can appropriately substitute more standard assessment practices.

To better understand the assessment practices described in this study, it is important to identify alternative and traditional assessment methods. Aebersold & Field (1997) proposed six alternative assessment methods for reading comprehension focusing on students' learning products, students' participation in the classroom and making learning processes observable. These methods are the following: (1) journals (audio and written), used to keep learners involved in the processes of monitoring comprehension, making comprehension visible, fitting new knowledge, applying knowledge, and gaining language proficiency; (2) Portfolios, provide a number of elements that could serve as a part of the evaluation of the students' work in the reading course; (3) Homework, used to let students learn what they do not know or what they need to ask questions about; this can be a valuable part of an assessment plan in a classroom; (4) Teacher assessment through observation consists on taking advantage of different classroom situations, group work, pair-work, students' reading exercises evaluate students' comprehension and participation; (5) Self-assessment, which asks students to reflect on their practices and achievements when reading; and (6) Peer assessment, which looks for the sharing of insights among classmates to assess participation, attentiveness and work produced by another classmate in a given activity.

The traditional method for assessing reading comprehension is testing. Aebersold & Field (1997) recognize the misuses and misconceptions that traditional tests have had on learning experiences, but they have also acknowledged that tests may provide valuable information on students' reading performances if they are designed and used with a more educative purpose. Testing depends not only on the teachers' abilities to convey the authority they exercise in a test, but also on their responsibility as educators to provide a learning atmosphere in which students can achieve as much as possible without unproductive tension and anxiety (Aebersold & Field, 1997). Testing in reading comprehension includes using materials which are closely related to the type of practice material implemented by the teacher to develop the reading skills (Heaton, 1998). Hughes (1999) also remarks on teachers' ability to design tests that can actually match specific assessment interests and students' abilities with the language. This is why Heaton (1998) remarks on the need for greater awareness of the actual process involved in foreign language reading comprehension, so that it is possible to produce appropriate exercises and test materials to assist in the mastery of text comprehension.

Although there may be a great variety of assessment and testing procedures to measure the reading ability, no method should be singled out as the best, as explained by Alderson (2000, p. 204) "It is certainly sensible to assume that no method can possibly fulfill all testing purposes... certain methods are commonplace merely for reasons of convenience and efficiency, often at the expense of validity, and it would be naïve to assume that because a method is widely used it is therefore valid". Therefore, the author believes "it is now generally accepted that it is inadequate to measure the understanding of text by only one method, and that objective methods can usefully be complemented by more subjectively evaluated techniques. This makes good sense, since in real life reading, readers typically respond to texts in a variety of different ways" (Alderson, 2000, p. 207).

Finally, Aebersold & Field (1997, p. 167) claim the need for "[...] reading teachers to become thoughtful, attentive, reliable assessors, able to use both alternative and traditional assessment measures that are beneficial to all". I believe that EFL teachers should be aware of the possibilities that traditional and alternative assessment bring to their classrooms. It is not a matter of choosing one over the other, but of being able to recognize the benefits each one has for making informed decisions.

Context of the Study

As stated in the introduction, the foreign language reading comprehension program at the Universidad de Antioquia demands from undergraduate students the demonstration of reading comprehension abilities in a foreign language as a requirement for graduation. To fulfill the requirement, students may take a twolevel reading comprehension course. Each level consists of 80 hours of instruction in English for developing students' reading abilities. The course has no academic credits and its final grade is reported as "pass" or "fail". Students may also take a foreign language reading proficiency test instead of taking the two-level course.

The purpose of the courses is that "students acquire the ability to extract implicit and explicit information from authentic reading materials by using the reading skills acquired during the courses"1. The objectives specify what students should be able to do when reading a text in English or French in terms of vocabulary, grammar, discourse and comprehension. The content is divided in units and it also specifies the number of hours to be devoted to each part of the content in the instruction. Finally, the syllabus states the way teachers should assess their students during the course, 50% a follow up, 25% a mid-term test and 25% a final test. These assessment practices and their corresponding percentages constitute students' final grade for passing or failing the course.

The program has around 5,000 students from all the academic departments of the Universidad de Antioquia. Between forty and fifty teachers are currently involved in the program. The majority of teachers are hired as hourly-paid instructors. Many of them also teach in other programs that include English for General Purposes. Six fulltime professors also work in the program. They and the headperson constitute the program's academic committee in charge of designing and leading the implementation of the reading comprehension policy.

Methodology

This case study (Creswell, 2007; Leedy & Ormrod, 2001) attempts to explore the assessment practices that teachers in the reading comprehension program use. The research question that led the study could be stated as follows: "What are the assessment practices of EFL teachers of the foreign language reading comprehension program at Universidad de Antioquia when measuring reading abilities?"

This methodology allows me to have a closer understanding of the teachers' practices in our context. The analysis of the data will enlighten my personal reflection on teaching and assessing reading comprehension. It will allow me to contribute to future improvements in the program as well as to the construction of local knowledge on teaching reading skills.

Participants

Fifteen English teachers and the head of the foreign language reading comprehension program at Universidad de Antioquia participated in this study. Teachers were chosen based on the following criteria: (a) those who had worked in the program for more than two years; and (b) those who had taught both levels of the reading comprehension courses. I decided to include their experiences and opinions because they have had closer contact with the students and with the assessment practices in the program. Fourteen of the English teachers are hourly-paid instructors and one is a full-time professor. The headperson is a full-time employee with teacher training and experience teaching reading comprehension. These opinions allow me to have a comprehensive view of the program and the assessment component seen from the administration perspective. Participants were identified as teachers 1 through 15 to protect their identities and keep the anonymity of their testimonies.

Data Collection

Data collected come from three different sources: (1) a documentary analysis of foreign language program regulations. These documents are the general framework for the foreign language reading comprehension courses. The official documents consulted were the following: (a) Acuerdo Académico # 0114 de 1997, proposed by the Academic Council of the University. This is the document that creates the foreign language reading comprehension program; (b) Orientación Pedagógica y Didáctica Programa de Competencia Lectora (2002), written by teachers and administrators of the Escuela de Idiomas. These documents provide some general teaching guidelines for the reading comprehension courses; (c) Memorando (2003), written by the program administrators, is a paper that presents a set of practical information for new and experienced teachers in the program; and (d) Reading comprehension syllabi (level I and II) (1998), designed by program administrators and teachers in the program

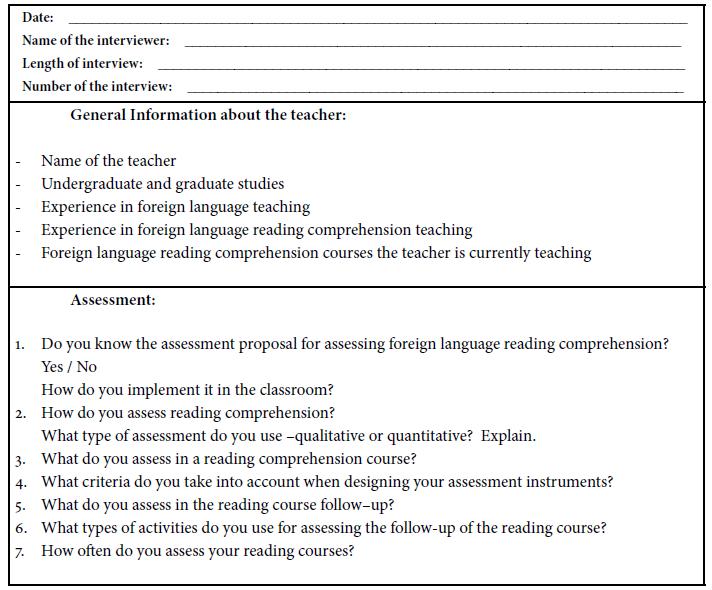

(2) A semi-structured interview with the head of the foreign language reading comprehension program. This instrument attempted to get information about the opinions and thoughts of the head of the program regarding teachers' assessment practices and the information provided by the program for teachers to assess the foreign language reading ability (See Appendix 1).

(3) A structured interview with 15 teachers from the reading comprehension program. It focused on the exploration of the practices they have when assessing foreign language reading comprehension in the classrooms (See Appendix 1).

Data Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. For the data analysis, I used the cycle proposed by Burns (1999). It consists of a 5-step process: I assembled the data collected from different sources and I devoted time to explore and examine data collected starting with developing codes to identify patterns about the different issues implicit in the study. This process of coding information helped me to reduce the data collected and identify specific categories of concepts or themes. I could make comparisons to see whether themes or patterns were repeated or developed across different data gathering instruments. In this part of the process it was necessary to triangulate all the information collected as a way to test the trustworthiness of the data and ensure ongoing reflections (Burns, 1999). According to Burns (1994, p. 272), "[...] triangulation is a way of arguing that if different methods of investigation produce the same result then data are likely to be valid". When I finished categorizing and comparing, I started interpreting and making sense of the meaning of the data in step four. Finally, in step five, I began presenting an account of the research findings. Once I identified the major categories, I chose the excerpts that best suited them and translated them into English.

Findings

Data analysis showed the following main findings regarding the teachers' practices in assessing reading comprehension skills:

Diverse Practices in Assessing Reading Comprehension

The interviews showed that there are shared beliefs regarding assessment in the reading comprehension courses. Each teacher uses his/ her own criteria and a great variety of instruments and emphasis on qualitative or quantitative approaches appear. Fourteen participants said that they implement quantitative assessment as well as the combination of qualitative and quantitative assessment for measuring foreign language reading comprehension. One can find a major difference in the teachers' explanation about what they include in the "follow-up" component. While some teachers use quizzes, multiple-choice tests, class participation or the reading of reports, others include presentations, workshops or assign a grade for attendance and interest shown in the activities. Teacher 13 describes his approach as follows:

[...] I have different forms of work. First, tests can be about all topics studied in the follow – up, or it can be an individual workshop. Then, we start working in groups, so that it is possible for students to have an individual reflection and then in groups...Later, we can start working with workshops in or out of the class.

Teacher 6 seems to have a different approach to assessment. He says:

[...] 50% of the grade is assigned to the follow up. There I include the workshop students have to complete in class. I observe students' interest in doing the exercise or if students do not pay enough of attention to the exercise. These are details that are taken into account for the grade.

Teacher 12 describes her assessment practices for the follow-up component:

[...] The follow up grade is obtained during class time. I usually do workshops, mid-term tests, quizzes, class participation, homework... I believe everything is valid.

As it is possible to perceive, there may be as many assessment practices as there are teachers in the program. One possible explanation for this may be the fact that the program has not defined clearly one assessment approach, even if there are some guidelines referring to the percentages for a midterm-exam, a final exam and follow-up. Another explanation may come from university autonomy that allows every teacher to design his/her program based on his/her own criteria for content selection and assessment. Diverse practices for assessing English reading may affect the achievement of the program's objectives.

Use of Quantitative Instruments to Evaluate Qualitatively

As the reading comprehension courses do not end with a numerical grade, many teachers seem to have difficulties assessing qualitatively. They tend to use instruments that allow them to calculate a number and then try to approximate it to a qualitative concept. They have to do it because the reading program asks them to do so. Teacher 10 acknowledges her use of quantitative instruments for obtaining a qualitative grade. She translates the numbers into a concept. Describing her assessment practice, she says:

[....] for designing the exams I use quantitative grades, but when I have to hand in the grade to the program administration I use pass or fail, because it has to be qualitative.

According to all the participants, the process of assessing students' reading abilities in the classroom consisted of a mixture between institutional regulations and teachers' decisions. The institutional documents and the interview with the head of the program reported clearly that assessment should be qualitative. The headperson expresses this condition:

[...] The courses have a qualitative assessment, as they are not part of any curriculum. The courses don't have credits for students, and therefore students' performance is expressed in terms of pass or fail.

Additionally, the "Memorando", a set of guidelines that the teachers receive to frame their work in the program, states clearly that the final grades are reported as "pass", "fail" or "dropped out". Although the program calls for qualitative assessment, the guidelines given to the teachers include percentages. The headperson explains the percentages:

[...] the assessment criteria stated for the foreign language reading comprehension program is based on the university rules, therefore none of the assessment components in the course should be higher than 25% from the grade. This is why the program proposes 25% of a mid-term exam, 25% of a final exam and a follow up of 50%.

Another issue that may get the teachers to mix quantitative and qualitative instruments comes from University program syllabi. It is a common practice in most universities and language centers where the majority of our teachers work to propose a quantitative assessment for all the undergraduate and graduate programs. Ours is maybe one exception to that tendency because the Academic Council from Universidad de Antioquia stated it like that in Acuerdo Académico 334 of 1997 as these courses require special skills.

Nevertheless, the headperson of the foreign language reading comprehension program had a different perception of teachers' decisions for implementing quantitative assessment instead of qualitative assessment. She acknowledges the problem in the teacher's practice of mixing qualitative and quantitative instruments:

[...] For teachers it has been a problem to assume a qualitative assessment. We have had meetings for discussing qualitative and quantitative assessment .We have discussed issues on both kinds of assessment. We have also made clear that teachers should be assessing qualitatively, but you will probably find a lot of teachers doing quantitative assessment... I believe teachers know what qualitative assessment means. The problem is that assuming qualitative assessment implies that they must evaluate their own teaching principles. It is not only a matter of defining institutional guidelines for assessing; it is also about the teachers' decision on how to assess...

One can see that in her opinion teachers may find qualitative assessment as problematic because it is more demanding and challenging for them. Apparently, even if there has been training in the two kinds of assessment, the difficulty remains.

Students' Lack of Familiarity with Qualitative Assessment Practices

Although the major focus of this paper is the teachers' assessment practices, I would like to address the students' lack of familiarity with qualitative assessment as a major finding. The reason I claim the importance of this issue comes from the fact that teachers' assessment practices were affected by this. In other words, this may have made teachers choose quantitative instruments rather than qualitative instruments as can be seen in the teachers' voices reported below.

For the majority of the teacher-participants in this study, their students were not familiar with qualitative assessment as they are used to being graded quantitatively in all the undergraduate programs. Students often claimed that they did not know how well or bad they performed in the course and asked teachers for clearer grades. They preferred a number rather than a grade expressed qualitatively. Teachers 2, 3, 6 and 11 share this opinion. Teacher 2 describes her students' discontent with their performance expressed as "pass" or "fail":

Students do not seem to understand what "pass" means, so they usually ask... What does "passing" mean. So, I try to explain them, but they understand easily when they receive a number as a grade. For example, if a student gets a 4.0 grade for the course, I translate that 4 into "pass".

To face this challenge, teachers try to make the qualitative assessment equivalent to the numbers students are used to. They usually design their own equivalency chart. This was found in the testimony of Teacher 10, presented above. Likewise, Teacher 14 describes his assessment practice:

[...] the reading comprehension program has the goal of assessing students qualitatively: pass or fail. However, I have seen how students do not understand these procedures, as they are used to quantitative assessment, therefore I assess quantitatively, but I hand in students results qualitatively.

The grade is probably one of the main motivational sources for our EFL students and in our university setting, it is better expressed with a number. This teacher uses a number rather than a word so that students have a clear idea of their performance. It seems that quantitative grades allow students to understand whether they were performing good or bad in the course. Teacher 11 believes the use of quantitative grades enhances his students' motivation in the course. His opinion is expressed as follows:

[...] I gave students quantitative grades because that is a cultural practice. If the student doesn't see grades, he/she starts losing interest in the subject, therefore it is necessary to provide qualitative grades. If you don't do it, students start asking for them.

Teachers' Lack of Familiarity with Alternative Assessment

Aebersold & Field (1997) state that it would be advisable for teachers to be familiar with alternative and traditional assessment. However, participants in this study seemed to have little knowledge about alternatives to tests and quizzes to assess reading comprehension. None of the participants mention assessment practices such as self-assessment, peerassessment, journals or portfolio (Hancock, 1994). These assessment instruments are recognized as informal, alternative, developmental, learningbased and student-centered as they pay more attention to the process; that is to say, the interaction between the reader and the text (Alderson, 2000).

The data analyzed also revealed a tendency of teachers to use traditional assessment instruments to measure students' reading comprehension. These assessment instruments are recognized as formal, teacher controlled, and standardized methods for measuring students' reading abilities (Cohen, 1994). Teachers' interviews showed the implementation of multiple-choice tests and quizzes as the most common reading assessment procedures in the classroom.

Teacher 6 explains that tests represent the best alternative for assessing his students' skills:

[...] I applied the assessment proposal from the program by doing tests. This is how I identified if students were able to infer, to write a summary from a reading... I always do workshops, quizzes, a mid-term and a final exam, so that I can have some order and control over the assessment of students... I usually do quizzes and workshop for units.

For the majority of teachers, tests are easier to design because they can anticipate the answers. Moreover, they can have the feeling they have more control over the learning process because every student has the same right answer. Assessment is also less time consuming because the grading time is shorter if the answers are known in advance. Many of the participants believe that issues such as students' attitude, behavior or motivation in class may serve the purpose of alternative assessment. Teacher 13 explains how he approaches some alternatives to testing and quizzes:

[...] I assessed students every class. Each workshop students complete, I try to assess it. When students start completing the exercise, I usually walk around the classroom; I observe students' work and that is how I realize if students are learning. If I notice that some students do not understand the exercise or the topic of the exercise, I try to explain by introducing some general comments.

Teacher 10 considers students' attitude in class as part of the grade too. She states:

[...] As part of the assessment I do during the course, I usually observe students' interest in class activities, class attendance and homework as important factors to complete students' grades.

This teacher, like many others in the study, finds a sign of interest in class behavior, homework completion and attendance. These features of positive attitude are compensated by a grade that complements the tests and quizzes. This is included as an assessment practice mainly because other instruments such as portfolio or journal are unfamiliar to many of our teachers.

Teachers' Concern for the Verification of Achievement of Learning Objectives

Most of the participants expressed a common concern for verifying the students' achievement of the learning objectives stated in the program. Eleven teachers stated that they tended to implement traditional assessment instruments, not only because they provide more precise information of what students can do when reading, but also because they assess what students are actually learning in the classroom. They believed that using these instruments favored objectivity, precision, reliability and a focus on product rather than process (Frodden, Restrepo & Maturana, 2004).

One important issue highlighted by Teacher 15 is the teacher's control of learning through the control of assessment in the use of tests. He says:

[...] I always implement workshops, quizzes, a mid-term exam and a final exam. This is for me to have an order and a good control of students' assessment.

The testimonies of teachers 10 and 13 reveal another interesting practice for achieving accountability. One of them describes that one of her classroom practices implies teaching for the test as a way to help students succeed in the course.

[...] I assess the topics presented during the classes. There is a complete preparation for quizzes or any test...there are usually workshops and exercises on the topics we have studied in class, then students should be prepared for the assessment.

[...] I try to focus on what we are teaching in class for assessing students... Those are the topics I take into account for a midterm or a final exam. The teachers believed that a test, whether midterm or final, should include all reading strategies learned during instruction. Therefore, the results of the test should provide a clear picture of students' performance when reading in a foreign language. Teacher 7 explains it as follows:

[...] I prefer to have a 25% mid-term exam and a 25% final exam so that students have some minimal standards to pass or fail the course. If students do not pass both tests, they should not pass the course.

The teachers' beliefs concerning accountability in the tests may be the result of their interpretation of the Memorando.

It is necessary to establish if the objectives of the courses were achieves, therefore we need to perform tests (exams, report, homeworks, quizzes, etc) that prove the achievement of objectives. These tests need to be as precise, reliable and valid as possible.

According to the document, learning is verified through tests and quizzes because the information resulting from these instruments is more precise and valid.

Conclusions

The analysis of the assessment practices used by EFL teachers of the reading comprehension program at the Universidad de Antioquia who participated in this study let me conclude that:

- Teachers have diverse practices in assessing reading comprehension.

- Teachers use quantitative instruments to evaluate qualitatively.

- Their students lack familiarity with qualitative assessment practices.

- Teachers lack familiarity with alternative assessment.

- Teachers are concerned about the verification of achievement of learning objectives.

Therefore, it is necessary to promote teachers' reflection on foreign language reading assessment practices not only for implementing better assessment practices with students, but also for introducing new guidelines for the reading program at Universidad de Antioquia. Although the study's results do not claim that teachers' professional development is a solution, it may be quite possible that assessment difficulties and misconceptions in the program may decrease if the program promotes discussion about reading assessment practices.

As a final remark, I would like to say that more studies are required to validate or reformulate these results. The sample and the instruments used reflect the situation at our University, but some of the assessment practices described here may be used somewhere else. I hope this study motivates other colleagues to explore their assessment practices and construct local knowledge around teaching reading comprehension in English.

1Translated from the foreign language reading comprehension courses syllabus at Universidad de Antioquia.

References

Aebersold, J. A., & Field, M. L. (1997). From reader to reading teacher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Alderson, J. C. (2000). Assessing reading. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Alyousef, H. S. (2005). Teaching reading comprehension to ESL/EFL learners. The Reading Matriz, 5(2), 143-154. [ Links ]

Aweiss, S. (1993). Meaning construction in foreign language reading. Atlanta, Ga: Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Association for Applied Linguistics (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED360850). [ Links ]

Block, E. (1986). The comprehension strategies of second language readers. TESOL Quarterly, 20, 436-494. [ Links ]

Brown, H. D. (2004). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices. New York: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. (1994). Assessing language ability in the classroom. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers. [ Links ]

Colombia, Universidad de Antioquia. (1997). Acuerdo académico No. 0114 de Septiembre de 1997. Documentos Jurídicos: Normas Jurídicas Universitarias. [ Links ]

Colombia, Universidad de Antioquia. (2002). Orientación pedagógica y didáctica programa de competencia lectora. Sección Servicios. Escuela de Idiomas. [ Links ]

Colombia, Universidad de Antioquia. (2003). Memorando. Sección Servicios. Escuela de Idiomas. [ Links ]

Colombia, Universidad de Antioquia. (1998). Programas de competencia lectora (nivel I y II). Sección Servicios. Escuela de Idiomas. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Cross, D. R., & Paris, S. G. (1987). Assessment of reading comprehension: Matching tests purposes and tests properties. Educational Psychologist, 22, 313-322. [ Links ]

Dubin, F., & Bycina, D. (1991). Academic reading and ESL/EFL teacher. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (pp. 195-215). Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers. [ Links ]

Frodden, C., Restrepo, M., & Maturana, L. (2004). Analysis of assessment instruments used in foreign language teaching. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 9(15), 171-201. [ Links ]

Gersten, R. (1999). Lost opportunities: Challenges confronting four teachers of English-language learners. The Elementary School Journal, 100(1), 37- 56. [ Links ]

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. L. (2002). Teaching and researching reading. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited. [ Links ]

Hancock, C. R. (1994). Alternative assessment and second-language study. Retrieved on November 2008, from ERIC Digest Web site: http://www.eric.ed.gov/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=ED376695 [ Links ]

Heaton, J. B. (1998). Writing English language tests. New York: Longman. [ Links ]

Hughes, A. (1999). Testing for language teachers. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Leedy, P. D., & Ellis Ormrod, J. (2001). Practical research: Planning and design. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill, Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Saricoban, A. (2002). Reading strategies of successful readers through the three phase approach. The Reading Matrix, 2, 1-13. [ Links ]

Singhal, M. (2001). Reading proficiency, reading strategies, metacognitive awareness and L2 readers. The Reading Matrix, 1, 1-9. [ Links ]

Jorge Hugo Muñoz Marín holds a Master's degree in English Teaching from Universidad de Caldas and a Specialization in Foreign Language Teaching from Universidad de Antioquia. He is a teacher in the Reading Comprehension Program at Universidad de Antioquia and a member of the research group eale (Enseñanza y Aprendizaje de Lenguas Extranjeras) at the same university.

Appendix 1: Forms for the Interviews*

Interview 1: With the Head of the Foreign Language Reading Comprehension Program

- What type of assessment is being implemented in the foreign language reading comprehension program? What are the guidelines given to teachers to assess foreign language reading comprehension?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses while assessing the foreign language reading comprehension program?

Interview 2: With the Teachers of the Reading Comprehension ProgramThis information is for the exclusive use of the interviewer.

* All interviews were designed in Spanish. They were translated for publication purposes.