Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

versão impressa ISSN 1657-0790

profile v.11 n.2 Bogotá jul./dez. 2009

English as a Neutral Language in the Colombian National Standards:

A Constituent of Dominance in English Language Education*

El inglés como idioma neutral en el marco de los estándares nacionales en

Colombia: un elemento constitutivo de dominación en la educación en inglés

Carmen Helena Guerrero Nieto*

Álvaro Hernán Quintero Polo**

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Colombia

*helenaguerreron@gmail.com

**quinteropolo@gmail.com

Address: Avenida Ciudad de Quito No. 64-81 Oficina 607. Bogotá, Colombia.

This article was received on April 30, 2009, and accepted on August 13, 2009. This article attempts to problematize the way the English language is used in official documents. We will focus on the "Estándares Básicos de Competencias en Lenguas Extranjeras: Inglés" (Basic Standards of Competences in Foreign Languages: English), a handbook issued by the Colombian Ministry of Education. We deem it as a vehicle used to spread a hegemonic and ideological influence and to alienate teachers' beliefs and practices within English language education. To be concise, here we discuss only neutrality as one broad category that emerges in our close examination of how the English language is constructed within the handbook. In this paper, we construct our main points around three forms of neutrality: prescription, denotation, and uniformity. Key words: English as a neutral language, English language education, foreign language standards, critical discourse analysis, symbolic power, language policies Este artículo intenta problematizar la manera como el idioma inglés es construido en documentos oficiales. Concretamente, nos centramos en los "Estándares Básicos de Competencias en Lenguas Extranjeras: Inglés", una cartilla emitida por el Ministerio de Educación colombiano. Consideramos este manual un vehículo usado para difundir la influencia hegemónica e ideológica y para alienar las creencias y prácticas de maestros dentro del campo de la educación de la lengua inglesa. Aquí, por razones de espacio, sólo se discute la neutralidad como una gran categoría que surge de un examen detallado de cómo el idioma inglés es construido dentro de la cartilla. En este escrito, presentamos nuestros puntos principales alrededor de tres formas de neutralidad: prescripción, denotación y uniformidad. Palabras clave: Inglés como un idioma neutro, educación del idioma inglés, estándares de idiomas extranjeros, análisis crítico del discurso, poder simbólico, políticas lingüísticas Introductory Theoretical Considerations on Neutrality and Dominance The discourse that portrays English as a neutral language has been around for a long time. On the one hand, there is the designation of English as the official language of the countries of the outer circle (Kachru, 1997), where many languages disputed this status. This situation has contributed to the construction of the notion of English as a neutral language based on the argument that by choosing English over all the local languages, conflicts would be avoided (Myers-Scotton, 1988; Skutnabb-Kangas, 2001). On the other hand, Pennycook (1994) asserts that the neutrality of English emerged from two main discourses: the discourse of linguistics and applied linguistics, where language was seen as a medium for communication (where "communication" was also constructed as a "neutral" activity); and the discourse of marketing where English, along with all the activities related to it, such as teaching methodologies, textbooks, teacher training, tests, materials and the like, are portrayed as a service industry. Neutrality of English language emerged as an issue that we were motivated to discuss while defining our main concern in a new study. This new study should add to the understanding of how language teachers in public schools in the district of Bogotá position themselves as regards government policies such as the ones related to language education. One main concern in the new research agenda is the need for language educators, from different regions in Colombia, to share and take a stand on the implementation of those policies. Consequently, from the legitimization of their voices, we can construct a discourse community (Gee, 1996) committed to national educational policies that value teachers' daily teaching experiences. It is justifiable to propose here a debate about the dominance expressed through the imposition of English as a neutral language. In our paper, we understand dominance as related to a dominant discourse of a reduced group of people i.e. elite, composed of terminologies established as norms and fallacious and reified ways of expression which influences the thought processes of the members of a community. Control and surveillance executed by those in power are characteristic activities of a domineering elite over a vast number of dominated ones. Since language is a significant constituent of the whole range of activity implicit in the teaching and learning of the English language, a dominant discourse represents, according to Fairclough (1995), a naturalized, hegemonic, ideological influence. Applied linguistics makes an important contribution to this understanding through critical discourse analysis. That is how we also intend to deconstruct the restricted view of English as a neutral language as presented in official documents from the perspective of our professional-academic orientation: a young academic tradition in applied linguistics that focuses on language as a key element in social issues. Our orientation is divergent from a dominant non-academic culture of English language teaching (ELT) which has been produced by an expansion from the Anglo North American paradigm of teaching English as a second language or teaching English as a foreign language (TESL or TEFL)1. The Anglo North American paradigm imposes demands on accountability and quality, bringing increased government instrumentalism. Government instrumentalism, in turn, relates to the decisions made by its representatives at the top level of a hierarchy of planning functions in the language- teaching operation (Quintero, 2007). These decisions affect not only the treatment of children and adults learning English, but also the careers of English language educators in schools and universities around the world, and Colombian settings cannot be an exception. This happens when English is "brought in" by a certain government or international policy as a force that affects wider curricular and administrative practices (Ruiz, 1984). For example, the implementation of the National Program of Bilingualism (PNB by its acronym in Spanish) carried out in Colombia through the "aid" of the British Council (i.e. the positioning of products of British publishing houses, the marketing of standardized tests that have the seal "certification of quality" of British universities, and imposition of short non-academic and skill-based teacher training courses) affects what happens in schools or universities. The presence of the British Council as foreign agents who control "aid" projects, such as the PNB in Colombia, a developing country, represents a political issue that has little to do with language per se. Nowadays the issues surrounding English language education become critical internationally, politically, and institutionally (Pennycook, 2004). In Colombia, we are preparing for the commemoration of the two-hundredth anniversary of independence from Spaniards. This event will take place next year. This connects post-colonial discussions of various types of imperialism that sustain themselves after the decline of an empire. Curiously, these discussions often turn to become centered around the role of English (Phillipson, 2008), not only in a national language policy, but in its influence on how education generally should be administered, whether from classroom practices of both teachers and students to curriculum decisions and actions of policymakers. Because of the imposed idea of English as a symbol of success within the world of international labor and as a symbol of educational status in many parts of the world (Shohamy, 2004), the aspirations of a wider community will also come into the picture.

The Object of Discussion in This Paper

The official document we analyze in this paper is the "Estándares Básicos de Competencias en Lenguas Extranjeras: Inglés" (Basic standards of competences in foreign languages: English). From this point on, we will use the Spanish term Estándares to refer to this official document issued by the Colombian National Ministry of Education (MEN by its acronym in Spanish) within its PNB (MEN, 2006a; 2006b)2. We decided to engage in a discussion of the way the power of English language is present in this official document. Like any other official document, it is a vehicle used to maintain and legitimate dominance and inequality (Phillipson, 2007). In this case, this presence relates to technical academic standards in the light of the "late capitalist society" (Fairclough, 1995) that is directed by a macro global-political, Anglo North American imperialism and its overall political and economical supremacy of which English language education is a part (Phillipson, 1992; Pennycook, 1994).

The Estándares has been an object of evaluation, not necessarily support, in Colombian academic events and publications in the last five years (e.g. Usma, 2009; Guerrero, 2008; Vargas, Tejada & Colmenares, 2008; Sánchez & Obando, 2008; González, 2007; Quintero, 2007; Cárdenas, 2006; Ayala & Álvarez, 2005, among others). The points some Colombian authors make about the Estándares relate to the need for genuine democratic participation of different sectors of the Colombian academic community and the need for an analysis that calls for positions from a socio-political perspective. Vargas, Tejada, & Colmenares (2008) refer to the Estándares as framed within the so called "Revolución educativa" (Educational revolution) and the "Plan de desarrollo educativo" (plan of educational development), official programs of the MEN that are based on three dictates: "ampliar la cobertura educativa, mejorar la calidad de la educación y mejorar la eficiencia del sector educativo" (broadening educational coverage, improving quality of education and improving the efficiency of the educational sector), according to the very Colombian minister of education, Cecilia Maria Velez White, in her "Carta abierta" (Open letter) that appears as an introduction to the Estándares. These three dictates result from industrialized models that contrast the view of education as a democratic activity. Furthermore, the Colombian authors who evaluate the Estándares agree on the need for an intra- and inter-textual perspective from which its fundamental goal of being "criterios claros y públicos" (clear and public criteria) that serve the purpose of guiding the educational community can be analyzed. It is obvious that the two perspectives mentioned above are so complex that it is impossible to discuss them fully in only one article. For this reason, we would like to focus on section three of the Estándares and three types of neutrality found in this document.

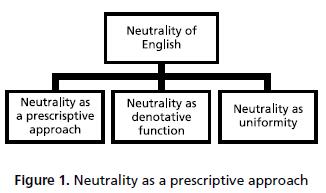

Section three of the Estándares, entitled "¿Por qué enseñar inglés en Colombia?" (Why teach English in Colombia?), is devoted particularly to highlighting the benefits of learning English. The authors start by establishing connections between internationalization and the need for a common language; then they present the advantages of learning a foreign language and, in the last part, state the reasons it is important to speak English. A close examination of the discourse used in the section aforementioned shows that English is deemed as having a neutral construction. This label is not new in terms of how English is regarded around the world, but is particularly salient in this document. The way in which English is constructed within the Estándares contributes to the enhancement of the neutrality attached to it and does so in three main forms: 1) English is neutral in the sense that throughout the document there is a strong emphasis on a prescriptive approach to the use of the language. 2) It is neutral because it only fulfills a denotative function. and 3) It is neutral because by presenting the language as one single standard variety, issues of social differentiation are erased and searches, rather, for uniformity. In the following section, we will discuss each of these forms of neutrality (See Figure 1).

Neutrality as a Prescriptive Approach

One's consideration of a prescriptive approach to teaching language as a form of neutrality arises from the idea that when the intention is to transmit a language as a set of fixed rules, which are detached from any relationship with the speakers of that language, the assumption is that language is not a vehicle by which inequality, discrimination, sexism, racism, and power can be executed. A prescriptive approach presents a language that does not have real speakers and, therefore, no conflicts of any sort.

Along the document, the emphasis is on the appropriate ways of doing things with language such as the rules students must know and how they must apply them, as stated in this excerpt:

Al igual que en otras áreas, los estándares de inglés son criterios claros que permiten a los estudiantes y a sus familias, a los docentes y a las instituciones escolares, a las Secretarías de Educación y a las demás autoridades educativas, conocer lo que se debe aprender. Sirven, además, como punto de referencia para establecer lo que los estudiantes están en capacidad de saber sobre el idioma y lo que deben saber hacer con él en un contexto determinado (Estándares, p. 11) (Bold in original).

As in other areas, English standards are clear criteria that allow students and their families, teachers and schools, the local and other education authorities, to know what must be learned. They also serve as a benchmark to establish what students are able to learn about the language and know what to do with it in a determined context.

In this excerpt, the authors of the document define the Estándares as "clear" criteria; this means that all the members of the school community must understand the same thing to ensure that everybody will follow the same patterns. The objective of these criteria is to inform everybody of what "must" be learned. By using specifically the verb debe and deben (must) in lines 3 and 5, the message is that of an imposition; the possibility of doing things differently does not exist. A variation in the word choice would give a different message; for example, using "should" or "could". The verb deber implies the obligation of doing something, and therefore establishes from the beginning an asymmetrical power relationship where those who "know" (MEN and its consultants) determine what those who do not know (school community) "must" learn.

Behind statements such as the one in the excerpt above lies a behavioral concept of education. The interest of the authors of the Estándares is to direct people's behavior by limiting what students "must" know in terms of the language. They still believe that it is possible to predict the result of instruction (Tumposky, 1984), that students will learn whatever teachers (or the State) define in the curriculum. The banking model of education (Freire, 1970) and the computer metaphor input=output are still in effect, regardless of all the controversy and more interactive and creative ways of looking at teaching, in general, and teaching languages, in particular.

To ensure that students will not deviate from the standards but continually observe the rules, the descriptors used within the document follow a pattern of controlled language. The following examples, taken from the descriptors set for the writing skill, serve to illustrate this point:

a) Copio y transcribo palabras que comprendo y que uso con frecuencia en el salón de clase (Estándares, Escritura, p. 19).

I copy and transcribe words I understand and which I use frequently in the classroom.

b) Escribo mensajes de invitación y felicitación usando formatos sencillos (Estándares, Escritura, p. 19).

I write messages of congratulations and invitations using simple formats.

c) Estructuro mis textos teniendo en cuenta elementos formales del lenguaje como la puntuación, la ortografía, la sintaxis, la coherencia y la cohesión (Estándares, Escritura, p. 27).

I structure my texts taking into account formal elements of language such as punctuation, spelling, syntax, consistency and cohesion.

Example a) above offers the most obvious narrow conception of what writing is within the Estándares. Here, the text conceives writing as a mechanical activity of "transcription" and students "copy" words from textbooks or boards; as such, writing is the lifeless and meaningless activity of putting isolated words on paper. Furthermore, writing, in this sense, responds to the concept that it is simply the transcription of the spoken word. We believe that this view of writing is not emancipatory but functional as can be inferred from Unesco's (1970) policies for literacy for developing countries. A functional concept of writing is concerned more with economic productivity than it is with human agency. This functional concept of writing implies learning writing skills such as copying or transcribing, which make one likely to become a functioning member of society who can enter the labor market (Blake & Blake, 2002; Papen, 2005), but not necessarily a critical person.

The excerpts that follow, b) and c), resemble the writing approaches in fashion before the 1980s where the emphasis was on the product of writing. Brown (1994) states that in the product approach, students' written pieces should a) meet certain standards of prescribed English rhetorical style; b) reflect accurate grammar; and c) be organized in conformity with what the audience would consider conventional. The focus of writing instruction was in imitating models of different types of texts, and the final products were evaluated according to the similarity with the original. In the examples mentioned above, students find themselves limited by "formats" they have to follow in order to preserve the correct form of the language.

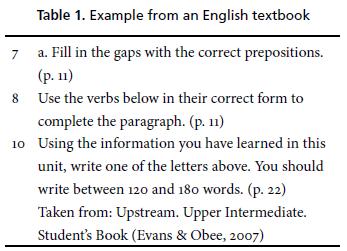

The common factor in these three examples, as in all the two hundred and eighteen descriptors included in the Estándares, is the absence of real meaning and purpose. The way the descriptors were written suggests that the activities held in class have the purpose of mastering patterns, structures, and formats. Students are asked to write an invitation for the sake of practicing the structure of an invitation; the content, purpose, addressee, relationship between them and the writer, occasion, media and other aspects are not included or considered. Instead, there is always stress on form (reinforced in the textbooks used in Colombia, such as the one in Table 1 below).

The same pattern of "modeling" is used to direct students' oral production. The following examples belong to the first and second level (first to fifth grade of elementary school) in relation to what must be achieved in monologue skill:

a) Recito y canto rimas, poemas y trabalenguas que comprendo, con ritmo y entonación adecuados (Estándares, Monólogos, p. 19).

I recite and sing rhymes, poems and tongue twisters that I understand with appropriate rhythm and intonation.

b) Participo en representaciones cortas; memorizo y comprendo parlamentos (Estándares, Monólogos, p. 19).

I participate in short performances; I memorize and understand speech.

c) Digo un texto corto memorizado en una dramatización, ayudándome con gestos (Estándares, Monólogos, p. 20).

I recite a short, dramatic text, helping myself with gestures.

d) Recito un trabalenguas sencillo o una rima, o canto el coro de una canción (Estándares, Monólogos, p. 20).

I recite a simple tongue twister or a rhyme, or sing the chorus of a song.

Rote learning, highly criticized lately in SLA theories, seems to be in effect here where students are encouraged to take in bits of language relying on memory skills, and then produce them observing the right rhythm and intonation. Rote learning is disguised by the inclusion of the word comprendo in the examples a) and b) above, but not in c) and d). The implication is that students should imitate the native speaker's3 accent and pronunciation, and the more similar the better.

This strategy, one that is not overtly explicit in these standards, was used by the British colonizers in Trinidad and Tobago (London, 2001). London discusses that during the late colonial period, the dominance of English was assured by certain curriculum and pedagogic practices. It is interesting to see that the same strategies used in the early 1900s to Anglicize people in Trinidad and Tobago, are the same suggested in the Estándares such as "hand-writing, spelling, recitation, rhymes, 'chats', and story telling" (p. 409) whose purpose was "to ensure acceptable pronunciation even at the expense of textual comprehension" (p. 410).

Linguistic creativity is then completely excluded and prevented by telling students to use non-verbal resources to get their messages across as stated in the excerpts below. The proponents of the PNB aim to preserve the standard variety as pure as possible because that is the one sanctioned as valuable in the linguistic market (Bourdieu, 1991):

a) Utilizo el lenguaje no verbal cuando no puedo responder verbalmente a preguntas sobre mis preferencias. Por ejemplo, asintiendo o negando con la cabeza (Estándares, Conversación, p. 19).

I use non-verbal language when I cannot respond verbally to questions about my preferences; for example, to deny or accept by nodding the head. 3 Conceiving of the native speaker of English as one, single, ideal speaker.

b) Refuerzo con gestos lo que digo para hacerme entender (Estándares, Conversación, p. 19).

I reinforce with gestures what I say to make myself understood.

c) Utilizo códigos no verbales como gestos y entonación, entre otros (Estándares, Conversación, p. 23).

I use non-verbal codes such as gestures and intonation, among others.

d) Formulo preguntas sencillas sobre temas que me son familiares apoyándome en gestos y repetición (Estándares, Conversación, p. 23).

I ask simple questions on familiar topics relying on gestures and repetition.

A prescriptive ideology of the Estándares ignores the very nature of language as a live and dynamic entity that is in constant flux and change; it is impossible to maintain an unchanged and unchangeable language regardless of the efforts of purists and prescriptivists (Bhatt, 2001; Makoni & Pennycook, 2005). Otherwise, there would not be an explanation for the emergence of the world Englishes. Only to cite an example, de Mejía (2006) documents the nativization of English in an elite bilingual (English-Spanish) school in Paraguay, where students have developed a new variety of English (and Spanish) called ASA English (after the acronym of the school: American School of Asuncion: ASA) which they use on a daily basis at school. Unfortunately, a prescriptive ideology has been motivated and supported by the popular view that other varieties of English are corrupted or degenerated and therefore they have no place in the classroom (Siegel, 1999).

As a result, learners of English who are exposed to this narrow approach become believers that English is a neutral language because there are patterns to be followed, the same for everybody, in every occasion, and in any part of the world.

Neutrality as a Denotative Function

In a speech event, when the focus is on the context, the function is called "referential"; this function is denotative (Jackobson, 1990) since it is used to talk about the world as it is. English around the world has been presented as a language that serves a mere denotative function in the sense that it is used to talk about the world in an unproblematic way. One probable cause of this is that the content of English language education is, in many cases, dictated by the textbooks, which are produced by the Anglo North American companies (Canagarajah, 1999; Valencia-Giraldo, 2006; Vélez-Rendón, 2003). These textbooks are characterized by an aseptic portrayal of reality that is transmitted to students as a fact so the topics of textbooks are about leisure, travel, celebrities, and the like (Pennycook, 1994). London (2001) states that during the late colonization period in Trinidad and Tobago, all the textbooks used were identical to those used in Ireland, Scotland and the West Indies. This pattern is maintained nowadays because the more "neutral" the textbooks are, the easier they can be marketed anywhere in the world (Pennycook, 1994; Valencia-Giraldo, 2006).

Another probable reason is the spread of English language teaching methodologies that originated in the Anglo North American countries and whose main concern is to train teachers to be efficient instructors; these methodologies are exported around the world in an identical format, regardless of the context, culture, or resources of each particular location (Canagarajah, 1999; Cárdenas, 2006; González, 2007; Pagliarini & De Asis-Peterson, 1999; Pennycook, 1994; Valencia- Giraldo, 2006). As a consequence the English classroom is a site to practice forms that are, in nature, detached from the local reality.

Likewise, in the Estándares there is no attempt to promote the use of the language to fulfill a purpose different from the denotative one. For example, the 'listening" descriptors aim at developing the skill to understand what is said in order to follow instructions, or to understand a story, or to identify connectors, and so on, as can be seen in the following descriptors taken from different levels:

a) Entiendo instrucciones para ejecutar acciones cotidianas (Estándares, Escucha, p. 26).

I understand instructions to perform everyday actions.

b) Reconozco los elementos de enlace de un texto oral para identificar su secuencia (Estándares, Escucha, p. 24).

I recognize the linking elements of an oral text to identify its sequence.

c) Comprendo preguntas y expresiones orales que se refieren a mi, a mi familia, mis amigos y mi entorno (Estándares, Escucha, p. 22).

I understand questions and oral expressions that refer to me, my family, my friends, and my surroundings.

For the other skills, the descriptors work in the same way:

d) Comprendo relaciones establecidas por palabras como and (adición), but (contraste), first, second... (orden temporal), en enunciados sencillos (Estándares, Lectura, p. 22. Italics in original).

I understand relationships between words such as and (addition), but (contrast), first, second ... (temporary order), in simple statements.

e) Escribo mensajes en diferentes formatos sobre temas de mi interés (Estándares, Escucha, p. 25).

I write messages in different formats on topics of my interest.

f) Utilizo una pronunciación inteligible para lograr una comunicación efectiva (Estándares, Escucha, p. 27).

I use intelligible pronunciation to achieve effective communication.

Descriptors constructed in this way help to perpetuate the idea that English is a neutral language because in our mother tongue we are aware of the different ways in which social relationships are established through language (for example, we are aware of which accents have prestige and which ones do not, how to address people of higher or lower hierarchy, etc. (Thompson, 2003). Throughout the two hundred and eighteen descriptors of the Estándares there is no sign that English is inextricably linked to social life (Bourdieu, 1991; Fairclough, 1992; 1995; Halliday & Hasan, 1985; Norton, 1989).

By obscuring the relationship between language and social life, the authors of the Estándares are also establishing a barrier between the language and the learners (as part of the society). When the standards limit what can be said and how it can be said, they are telling the users that the language does not belong to them and that the language serves only certain purposes. Speaking a language is a matter of making meaning (Halliday, 1974; Norton, 1989) but if speakers are constrained by formats, models, rules, etc., there is a risk of silencing them (Norton, 1989) because they cannot relate to the language.

In the Estándares students are told they can write about their interest but using specific formats; they can tell a story but observing the grammatical rules; they can participate spontaneously in a conversation but with good pronunciation. All in all, the Estándares privileges form over content because, in that way, it is easier to perpetuate the idea that English is a neutral language. If its function is merely denotative, the stance of the speaker is not considered nor the multiple interpretations triggered by a text.

The authors of the Estándares state that according to the level (Básico, Pre-intermedio I and Pre-intermedio II), a particular function of the language will be emphasized:

a) En el nivel principiante se hace mayor énfasis en las funciones demostrativas del discurso (Estándares, p. 29).

b) In the beginners level the emphasis is greater on the referential functions of language.

En los niveles básicos se busca fortalecer el dominio de funciones expositivas y narrativas (Estándares, p. 30).

In the basic levels the aim is to strengthen the mastery of expository and narrative functions.

c) En los últimos grados se busca fortalecer el dominio de funciones analíticas y argumentativas, aunque no con el mismo nivel de su lengua materna (Estándares, p. 30).

In the upper grades the objective is to strengthen the dominance of analytical and argumentative functions, but not on the same level as students' mother tongue.

Underneath this graded function emphasis lies on the concept that a limitation in a linguistic code is the same as a limitation in thinking ability; consequently, six to ten-year-old children are only capable of using language in a denotative way, to describe their surroundings without taking a stand. For this reason, only the referential function receives attention, although the superficial structure of example a) suggests something different. By stating that se hace mayor énfasis (there will be greater emphasis), the implication is that all language functions will receive attention, but the emphasis will be on the referential one. If we suppose this is true, there should be descriptors aimed at developing all functions. However, there is a mismatch between that statement and the descriptors set for this level because none of them refer to using the language with a purpose different from denotation.

The same situation happens with the statement in example c) because, although the authors warn that the analytic and argumentative functions cannot have the same level as has the mother tongue, there are only three descriptors that remotely relate to the goal:

a) Expreso mi opinión sobre asuntos de interés general para mí y mis compañeros (Estándares, Monólogos, p. 25).

I express my opinion about issues of general interest for my classmates and me.

b) Asumo una posición crítica frente al punto de vista del autor (Estándares, Monólogos, p. 26).

I take a critical position regarding the views of the author.

c) Identifico los valores de otras culturas y eso me permite construir mi interpretación de su identidad (Estándares, Monólogos, p. 26).

I identify the values of other cultures and this allows me to build my interpretation of their identity.

It is interesting that the three descriptors above are included in the Monólogo skill, which means that students do not interact with others to develop or challenge their opinions. If there were a real interest in promoting argumentative and analytic functions, these would be included in all the skills to give students the opportunity to strengthen their abilities by using different modes of language for their purposes. Besides, it is unrealistic that after nine years of controlled production in the L2, students will feel comfortable presenting their opinions and critiques in English.

Neutrality as Uniformity

Uniformity is another type of neutrality in English. The aim is to reproduce uniformity in two ways: language variety and social behavior. We have stated earlier that textbooks present an aseptic portrayal of reality. In the same line, English is presented as an aseptic language that exists in a vacuum, free of any kind of contamination in a pure and fixed state (and as such it must be kept), where everybody speaks in the same way. Students are not made aware that, as in any other language, English presents different varieties that respond to regional origins, gender, sex, education, age, and context in which the language is used.

With English being one of the most used languages in the world, there is wide variability within it. The problem is that English is conceived as having one single variety that by default is Standard American English or Standard British English, but whatever the standard, it cannot be matched to any real group of people; it is an imaginary language that resides in an ideal speaker (Lippi-Green, 1997). This is the language introduced in the classroom through international textbooks (Pennycook, 1994), and through the Estándares in the PNB. The following excerpts, serve to illustrate this point:

a) Identifico elementos culturales como nombres propios y lugares, en textos sencillos (Estándares, Lectura, p. 20).

I identify cultural elements such as proper names and places in simple texts.

b) Identifico el tema general y los detalles relevantes en conversaciones, informaciones radiales o exposiciones orales (Estándares, Escucha, p. 22).

I identify the general topic and the relevant details in conversations, information on the radio or oral presentations.

c) Comprendo relaciones de adición, contraste, orden temporal y espacial y causa-efecto entre enunciados sencillos (Estándares, Lectura, p. 24).

I understand relationships of addition, contrast, spatial and temporal order, and cause-effect between simple statements.

d) Identifico personas, situaciones, lugares y el tema en conversaciones sencillas (Estándares, Escucha, p. 26).

I identify people, situations, places and the topic in simple conversations.

These descriptors for reading and listening, where students could be exposed to different varieties of the language and encouraged to appreciate its differences, do the opposite. In example a) the cultural experience is reduced to the identification of people's names and to the names of places. These types of activities give way to stereotyping because students might get the idea that certain names are attached to certain cultures along with certain social practices, particularly considering that English textbooks tend to be very ethnocentric, e.g. portraying only the positive characteristics of the Anglo North American people; as a consequence, students will see the world in black and white in spite of the colorful layout of textbooks (Pennycook, 1994).

The same is true in examples b) and d). Besides, the use of the verb Identifico restricts the intellectual activity students perform; they are simply expected to pinpoint information they hear or read without engaging their personal beliefs or ideas. Example e) shows a recurrent pattern in the descriptors: that the relevance of the activity is given to the structure of a text; students have to identify the relationships among the components of the text, but there is no mention of why it is written in a particular way; in this sense, the relationship between the author and the text is ignored.

The insistence on denying the existence of other varieties of English (along with denying the existence of the speakers of those varieties) nurtures an ideal state in which one day we all will be able to speak exactly the same way and live in endless harmony. This plan is already in progress as in some workplaces employees are asked to modify their own linguistic persona and adopt a more homogeneous corporate one (Cameron & Block, 2002).

The second aim of the neutrality of English in relation to uniformity is to perpetuate, reproduce or promote a pattern of social behavior where students are positioned as passive consumers of social norms enacted via language (Auberbach, 1993; Pennycook, 1994). The following excerpts show how specific language choices and grammatical structures indicate the role of students as users of the language:

a) Utilizo variedad de estrategias de comprensión de lectura adecuadas al propósito y al tipo de texto (Estándares, Lectura, p. 26).

I use a variety of reading comprehension strategies appropriate to the purpose and type of text.

b) Utilizo estrategias adecuadas al propósito y al tipo de texto (activación de conocimientos previos, apoyo en el lenguaje corporal y gestual, uso e imágenes) para comprender lo que escucho (Estándares, Escucha, p. 26).

I use appropriate strategies according to the purpose and text type (activation of prior knowledge, body language and gestures support, and use of pictures) to comprehend what I listen to.

c) Monitoreo la toma de turnos entre los participantes en discusiones sobre temas preparados con anterioridad (Estándares, Conversación, p. 25).

I monitor turn-taking among participants in discussions on topics prepared in advance.

The three examples use action verbs to give the idea that students are active participants in the process, autonomous individuals who are in control of their own learning; but looking at the predicate of each one of the sentences, the message is different. In examples a) and b), the purpose is to use strategies to understand a text (written and oral). Therefore, students are supposed to become efficient readers or listeners (See Table 2). These types of goals can be associated with the language of business in the capitalist world, where efficiency is a "must" to assure economic profit (Tollefson, 1991; Tumposky, 1984). The instrumentality of these descriptors is apparent because there is a preeminence of technique over enjoyment.

Table 2.

In example c) students' future behavior in any conversation is being directed by observing how turn taking occurs. The implication of monitoring is that students have to pay attention and replicate the pattern; they are not asked or expected to problematize turn taking practices, to question unfair distribution of talk time depending on age, gender, regional origin, hierarchy, social status, and the like (Norton, 1989). Consequently, the intention by choosing the verb "monitor" is to hide the fact that turn taking and all the day-to-day social practices are sites where asymmetric power relationships are enacted (Auberbach, 1993).

Leaving social practices unexamined contributes to the perpetuation of forms of inequality, submission, and discrimination, particularly taking into account that learning a language implies acquiring a way of looking at the world (Goke-Pariola, 1993). If schools serve the interests of dominant groups interested in maintaining the status quo, they are facilitating their task of exerting symbolic power, because one cannot resist or contest what one does not perceive as unfair, and therein lies the strength of symbolic power (Bourdieu, 1989).

Writing is another skill in which students' use of language is highly controlled in order to preserve the uniformity of their written production according to the norms set by the Estándares:

a) Escribo mensajes en diferentes formatos sobre temas de mi interés (Estándares, Escritura, p. 25).

I write messages in different formats about topics of my interest.

b) Diligencio efectivamente formatos con información personal (Estándares, Escritura, p. 25).

I fill in forms with personal information effectively.

c) Organizo párrafos coherentes cortos, teniendo en cuenta elementos formales del lenguaje como ortografía y puntuación (Estándares, Escritura, p. 25).

I organize coherent short paragraphs, taking into account such formal elements of language as spelling and punctuation.

Students are directed to follow the rules so that, although the action verb possesses the students as agents, it is the format and conventions that are in control of what is produced and how. Students are positioned as mere instruments, by which texts are written, and in this way, their agency is not acknowledged; they are not constructed as the verbs misleadingly indicate, in control of their own learning and owners of the language, but as submissive consumers of norms. A final note of caution needs to be made regarding this last point: students might be conceived of as passive by the authors of the Estándares but they are certainly not, as stated by Canagarajah (1999): "Whatever policies the colonies adopted, the locals carried out their own personal agendas, and foiled the expectations of their masters" (p. 64).

Conclusion

To provide a rationale of why the MEN chose English over other languages for its PNB, the authors of the "Estándares" relied on the discourses about the neutrality of English that have been produced since the 18th century. Bringing that universal discourse to the local context seems unproblematic because the MEN can pretend they are providing the solution to the deep needs of our country by including the teaching of the "magical" language.

One of the forms of neutrality is the dominance of a prescriptive approach in the standards. The descriptors aim at producing students who use the language within strict limits that control what they can do with it. The so-called productive skills (speaking and writing) establish the appropriateness of students' outcomes. When speaking, learners have to produce correct sentences and observe appropriate pronunciation; the definition of "appropriate" responses contrasts students' pronunciation with that of native speakers of the variety approved as the standard. When writing, they have to follow the patterns given, where the predominance is on the form and not on the content. Ideas of meaningful and purposeful learning do not have a place in these standards.

The neutrality of English is also embodied by attaching to it only a denotative function. The different activities students are expected to perform in the English class are aimed at perpetuating an idealized image of English and everything associated with it, as a "fantasyland" where everybody is happy and lives in a perfect world. These descriptors are written in such a way that students are not invited to interrogate social practices. Rather, they are asked to remain passive and submissive and participate diligently in the social order. It is ironic that something as inherently social as language is introduced in a national program as just an innocent and isolated tool.

Preventing students from playing with the L2, from getting contact with other varieties of the language, and from interacting with different speakers, that is, keeping them in a vacuum makes neutrality take another form: uniformity. The purpose of uniformity is to fulfill the dream of purists to maintain the language as unchanged as possible, where every speaker observes the rules and sounds exactly the same. A second purpose is to promote a single view of the world where social behaviors are dictated by the dominant groups; we all should copy the rules for the social practices of these groups and assume our roles to maintain an undisruptive social system.

The Estándares in its third section contains examples of how a dominant discourse in English language education favors a professionalism that incorporates prescriptive views of teaching and excessive needs for accountability and controlled quality. This is channeled through foreign agents that belong to the private sector, who are fine tuned to commercial survival (Quintero, 2003). Behind the Estándares there are principles of learner-centeredness. They are derived from skillbased and non-academic education that turns into manipulative activities and objective competences used to control the users of the language.

If the search is for a shared language, then an explicit declaration of what it implies should be made. To share a language means to be part of a discourse community, not for speaking the same tongue, but for sharing the same values and beliefs this discourse community has and, even more, for performing a role within this specific group of people (Gee, 1996). This performance can be achieved through the construction of empowering settings in which every actor can access the discourse and can make of it a linguistic capital in order to understand the challenges of their tasks and their alternatives for redefinition from their teaching and learning practices.

Nevertheless, some characteristics of the official document that we read hinder the construction of such settings. The audience to whom the Estándares is addressed is composed mainly of Colombian teachers. They are affected by the nonaligned status of English, which has been a key aspect in the promotion of the official document. It contains a language that serves mere instrumental purposes instead of enriching teachers' discourse. It limits their access to other characteristics of the English language as a vehicle to broaden the ideological and cultural practices of the Anglo NorthAmerican countries.

* We wrote this article as part of the initial activities in the construction of a research proposal, which is now under evaluation in the Centro de Investigaciones y Desarrollo Científico of the Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas.

1 ELT, TESL, and TEFL, among others, are typical acronyms that represent discoursally loaded concepts that deserve being further analyzed rather than taken for granted (Holliday, 1998).

2 The word "Estándares" is used to refer to the document "Estándares Básicos de Competencias en Lenguas Extranjeras"; the word "standards" will be used to refer to the actual standards (descriptors) adopted by the Ministry of Education, and presented in the document "Estándares".

3 Conceiving of the native speaker of English as one, single, ideal speaker.

References

Auberbach, E. (1993). Re-examining English only in the ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 27(1), 9-32. [ Links ]

Ayala, J., & Álvarez, J. A. (2005). A perspective of the implications of the Common European Framework implementation in the Colombian socio-cultural context. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 7, 7-26. [ Links ]

Bhatt, R. (2001). World Englishes. Annual Review of Anthropology, 30, 527-550. [ Links ]

Blake, B., & Blake, R. (2002). Literacy and learning: A reference handbook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P . (1989). Social space and symbolic power. Sociological theory, 7(1), 14-25. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Brown, H. (1994). Teaching by principles. Upper Saddle River, nj: Prentice Hall Regents. [ Links ]

Cameron, D., & Block, D. (2002). Globalization and language teaching. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Canagarajah, S. (1999). Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, R. (2006). Considerations on the role of teacher autonomy. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8, 183-202. [ Links ]

Colombia. Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN]. (2006a). Políticas educativas. Enseñanza del inglés en Colombia. Retrieved July 22, 2009 from Web site: http://www.britishcouncil.org/es/men-2-presentacion.pdf [ Links ]

Colombia. Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN]. (2006b). Estándares básicos de competencias en lengua extranjera: inglés. Formar en lenguas extranjeras: le reto. Retrieved June 09, 2009 from Web site: http//www.colombiaaprende.edu.co/html/mediateca/1607/articles.115375_archivo.pdf [ Links ]

Evans, V., & Obee, B. (2007). Upstream upper intermediate B2+. Student's book. Newbury, Berkshire: Express Publishing. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (1995) Critical discourse analysis. The critical study of language. Essex: Longman. [ Links ]

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum. [ Links ]

Gee, P. (1996). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses (2nd ed.). London: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Goke-Pariola, A. (1993). Language and symbolic power: Bourdieu and the legacy of Euro-American colonialism in an African society. Language and Communication, 13(3), 219-234. [ Links ]

González, A. (2007). Professional development of EFL teachers in Colombia: between colonial and local practices. Íkala, 12(18), 309-332. [ Links ]

Guerrero, C. H. (2008). Bilingual Colombia: what does it mean to be bilingual within the framework of the national plan of bilingualism? profile Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 10, 27-45. [ Links ]

Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (1985). Language, context, and text: Aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective. Victoria: Deakin University. [ Links ]

Halliday, M. A. K. (1974). Explorations in the functions of language. New York, Oxford, Amsterdam: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Holliday, A. (1998). Evaluating the discourse: the role of applied linguistics in the management of evaluation and innovation. In P. Rea-Dickins & K. Germaine (Eds.), Managing evaluation and innovation in language teaching: building bridges (pp. 195-219). Harlow, Essex: Addison Wesley Longman Limited. [ Links ]

Jackobson, R. (1990). The speech events and the functions of language. In L.Waugh & M. Monville-Burston (Eds.), On language (pp. 259-293). Cambridge, MA, London: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Kachru, B. (1997). World Englishes and English-using communities. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 17, 66-87. [ Links ]

Lippi-Green, R. (1997). English with an accent. Language, ideology, and discrimination in the United States. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

London, N. (2001). Language for the global economy: some curriculum fundamentals and pedagogical practices in the colonial educational enterprise. Educational Studies, 27(4), 393-423. [ Links ]

Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (2005). Disinventing and (re) constituting languages. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 2(3), 137-156. [ Links ]

Mejía, A. M. de (2006). Bilingual education in Colombia: Towards a recognition of languages, cultures, and identities. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8, 152-168. [ Links ]

Myers-Scotton, C. (1988). Patterns of bilingualism in East Africa. In C. Paulston (Ed.), International handbook of bilingualism and bilingual education (pp. 203-24). Westport CT: Greenwood Press. [ Links ]

Norton, B. (1989). Toward a pedagogy of possibility in the teaching of English internationally: People's English in South Africa. TESOL Quarterly 23(3), 401-420. [ Links ]

Pagliarini, M., & De Assis-Peterson, A. (1999). Critical pedagogy in ELT: Images of Brazilian teachers of English. TESOL Quarterly, 33(3), 433-452. [ Links ]

Papen, U. (2005). Adult literacy as social practice: More than skills. London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Pennycook, A. (1994). The cultural politics of English as an international language. London & New York: Longman. [ Links ]

Pennycook, A. (2004). Critical moments in a tesol praxicum. In B. Northon & K. Toothey (Eds.), Critical pedagogies (pp. 327-345). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Phillipson, R. (2007). Linguistic imperialism: a conspiracy, or a conspiracy of silence? Language Policy, 6(3-4), 377-383. [ Links ]

Phillipson, R. (2008). The linguistic imperialism of neoliberal empire. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 5(1), 1-43. [ Links ]

Quintero, A. (2003). Teachers' informed decision-making in evaluation: corollary of elt curriculum as a human lived experience. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 122-138. [ Links ]

Quintero, A. (2007). The place of language teachers' decision-making in the hierarchy of planning functions in the language-teaching operation. ASOCOPI Newsletter, March, 2007, 8-9. Retrieved July 23, 2009 from ASOCOPI Web site: www.asocopi.org. [ Links ]

Ruiz, R. (1984). Orientations in language planning, NABE Journal, 8, 15-34. [ Links ]

Sánchez, A., & Obando, G. (2008). Is Colombia ready for "bilingualism"? PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 9, 181-196. [ Links ]

Shohamy, E. (2004). Assessment in multicultural societies: applying democratic principles and practices to language testing. In B. Northon & K. Toothey (Eds.), Critical pedagogies (pp. 72-92). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Siegel, J. (1999). Stigmatized and standardized varieties in the classroom: Interference or separation? TESOL Quarterly, 33(4), 701-728. [ Links ]

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (2001). Linguistic human rights in education for language maintenance. In L. Maffi (Ed.), On biocultural diversity. Linking language, knowledge and the environment (pp. 397-411). Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institute Press. [ Links ]

Thompson, J. (2003). Editor's introduction. In J. Thompson (Ed.), Language and symbolic power. Pierre Bourdieu. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Tollefson, J. (1991). Planning language, planning inequality: Language policy in the community. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Tumposky, N. (1984). Behavioural objectives, the cult of efficiency, and foreign language learning: Are they compatible? TESOL Quarterly, 18, 295-310. [ Links ]

Unesco (1970). Functional literacy: Why and how. Paris, France: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Usma, J. (2009). Education and language policy in Colombia: exploring processes of inclusion, exclusion, and stratification in times of global reform. profile Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 11, 123- 141. [ Links ]

Valencia-Giraldo, S. (2006). Literacy practices, texts, and talk around texts: English language teaching developments in Colombia. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8, 7-37. [ Links ]

Vargas, A., Tejada, H., & Colmenares, S. (2008). Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras (inglés): Una lectura crítica. Lenguaje, 36(1), 241-275. [ Links ]

Vélez-Rendón, G. (2003). English in Colombia: Asociolinguistic profile. World Englishes, 22(2), 185-198. [ Links ]

Carmen Helena Guerrero Nieto, holds a Ph.D in Second Language Acquisition and Teaching, University of Arizona and an m.a. in Applied Linguistics to tefl, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. She is an assistant professor at Universidad Distrital, Bogotá, and a member of the research group Lectoescrinautas. Her research interests are discourse analysis and language pedagogy.

Álvaro Hernán Quintero Polo, holds an m.a. in Applied Linguistics to tefl, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. He is an assistant professor at Universidad Distrital, Bogotá, and a member of the research group Lectoescrinautas. His research interests are discourse analysis, language pedagogy, and curriculum evaluation.