Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Print version ISSN 1657-0790On-line version ISSN 2256-5760

profile vol.11 no.2 Bogotá July/Dec. 2009

ELT Materials: The Key to Fostering Effective

Teaching and Learning Settings

Materiales para la enseñanza del inglés: la clave para promover

ambientes efectivos de enseñanza y aprendizaje

Astrid Núñez Pardo*

María Fernanda Téllez Téllez**

Universidad Externado de Colombia, Colombia

*astrid.nunez@uexternado.edu.co

**maria.tellez@uexternado.edu.co

Address: Calle 12 No. 1-17 Este. Universidad Externado de Colombia. Bogotá, Colombia.

This article was received on January 19, 2009 and accepted on June 20, 2009. Our article aims at providing teachers with an overview for materials development, taking into account the experience gained by two teachers in the English Programme of the School of Education at Universidad Externado de Colombia in Bogotá. This experience has helped us achieve better teaching and learning conditions for our university students in their quest to learn a foreign language. This paper addresses the issue of the role of teachers as textbook developers, and how they can meet materials development demands by integrating a clear conceptualisation and set of principles as well as their essential components. Key words: Materials development, text developers, materials development demands, effective teaching and learning settings Este artículo brinda a los profesores de inglés un panorama del desarrollo de materiales con base en nuestra experiencia como profesoras del Programa de Inglés de la Facultad de Educación de la Universidad Externado de Colombia, en Bogotá. Esta experiencia ha permitido mejorar las condiciones de aprendizaje de nuestros estudiantes de inglés como lengua extrajera. El documento se centra en el papel de los profesores como diseñadores de textos para cursos de inglés, y cómo ellos pueden satisfacer las exigencias que demanda el desarrollo de materiales, integrando una clara conceptualización, sus principios y sus componentes esenciales. Palabras clave: Diseño de materiales, diseñadores de textos, requisitos para el desarrollo de materiales, ambientes efectivos de enseñanza-aprendizaje Introduction Our intention is to motivate EFL/ESL teachers to exploit their creativity and embark upon the fascinating task of developing their own materials, applying their valuable knowledge and experience as regards English learners' needs, particularly in the case of English for speakers of other languages (ESOL). To do so, the first aspect to take into account is to include some considerations with regard to the issue of teachers as materials developers and their contribution to teacher development. The second one is to provide some reflections about language teaching and learning as essential demands when developing materials. And the third is to present the concept, principles and components for adapting didactic materials.

Materials Development for Teacher Development

Teachers have realized that a whole industry has been built up around changing teaching resources and methodologies. Considerable attention is now being paid to developing instructional materials and recognising the importance of teaching resources and strategies used to maximize students' language learning.

Most EFL/ESL teachers are creative professionals who have the potential to explore their creativity and embark upon the fascinating task of developing their own didactic materials based not only on their teaching experience, but also on their expertise in the cognitive and learning processes needed by EFL/ESL learners, as described by Pineda (2001). Therefore, this task should not be confined to text developers exclusively since there is no complete textbook that fulfils both learners' and teachers' expectations, as concluded by Núñez & Téllez (2008).

For many decades, materials development was merely the production accompanying a wide range of learning resources to illustrate methods. However, things have started to change due to teachers' awareness of two issues: first, the huge production in the interest of methodologies and materials used for teaching; and second, the importance of including students' voices in order to update teaching materials in terms of the way learners would like to learn and what they need to learn in today's increasingly globalized world.

We do believe that developing materials to enhance teachers' pedagogical practices involves reflection and practice because, as Goethe stated, "Knowing is not enough. We must apply. Willing is not enough. We must do", meaning that reflection and action go together, hand in hand, from the onset of materials development.

Then, pondering on the teaching process is vital in the search for developing materials that satisfy students' learning objectives and styles, preferences, and expectations. Gardner (1993) envisioned the multiple intelligences model in which he asserts that human beings are unique and have eight native intelligences he termed as interpersonal, intrapersonal, musical, spatial, kinaesthetic, logical-mathematical, linguistic, spiritual and naturalistic that must be acknowledged and developed when teaching a language. This, in turn, should lead teachers to reflect upon classroom procedures in unique paths.

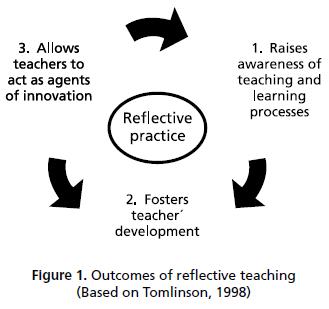

Besides, in agreement with Schön (1983; 1987), reflective practice is a two-fold concept implying a dialogue of thinking and doing through which teachers become more skilful. Thus, the onset of teachers' reflection is the individual assessment of the EFL classroom, which enables them to make decisions when they create or adapt materials that fulfil particular students' needs and learning settings.

This leads us to conclude that teachers should devote plenty of time to the demanding task of constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing their daily pedagogical practice as a means of facing decision making, improving their teaching performance, innovating in their classes and, so, developing professionally. This practice can be summarised in the following figure, based on Tomlinson' insights about both materials and teachers' development (1998).

Materials Development Demands

Acknowledging that students learn at particular speeds and succeed in different manners, teachers should consider this diversity when teaching the target language and when developing their materials trying, at the same time, to keep a balance among students' language learning needs, preferences, motivations and expectations, their affective needs, and the institutional policies.

In the same way, and following Oxford (1997), teachers should also bear in mind that since knowledge is socially built, fostering pair and group learning activities is a "must" as they enhance motivation, improve self-esteem in students, and lower anxiety and prejudice. Additionally, they are helpful in sharing information, cooperating with each other's learning, enhancing commitment to subject learning as well as to developing a sense of belonging to the educational institutions and classmates.

Furthermore, it is relevant to highlight the valuable element of enjoyment in our practices and in the material being produced for our students, which results in having students motivated and engaged in a comfortable, warmhearted and challenging learning atmosphere. To that extent, Tosta (2001) and Small (1997) assert that an essential element of success in an EFL classroom is the possibility for the class to be an opportunity to learn and the students to find learning enjoyable. For this reason, teachers ought to create materials that promote pleasant learning settings, thereby fostering motivation, interaction, and long-term learning.

Moreover, language learning materials constitute a key factor in creating effective teaching and learning environments. Following Tomlinson (1998), these materials could be considered effective if they facilitate the learning of a language by increasing learners' knowledge, experience and understanding of it and, simultaneously, helping learners learn what they want and need to learn.

In addition, the effectiveness of materials used for language teaching depends largely on how meaningful, relevant and motivating they are to the learners. These three conditions are met when there is a match between the materials and tasks proposed in them, with the learners' needs, interests, attitudes and expectations. In other words, teachers should do their best to develop the most effective, appropriate, and flexible materials for their students and their programs.

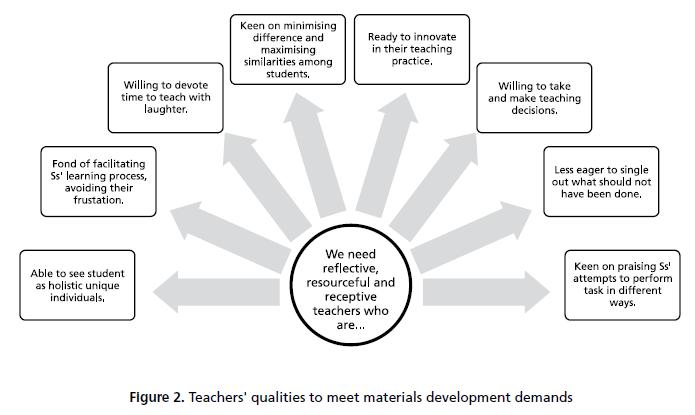

Above all, materials development requires designers to be reflective, resourceful and receptive (RRR) agents with regard to their teaching practice, besides becoming more willing to take risks and make decisions related to the way they handle classes, and being less willing to single out what should not have been done as well as attentive to complimenting and praising their students' attempts to perform tasks in a different manner as there are not necessarily incorrect ways to do things, but rather different ways to do them.

Consequently, RRR teachers inspire and do most of these things: devote time to teaching, facilitating, and guiding their students' learning process; implement changes or innovations in their teaching practice; see students as holistic, unique individuals; minimize differences and maximize similarities among students; match students' language learning needs, concerns and motivation; comply with institutional targets and students' affective needs in their teaching methodology; create a language learning atmosphere that keeps students' attention and imagination going; envision and cope with the syllabus models; and deal with the types of learning/teaching activities, the role of the learners as well as that of the instructional materials.

Figure 2 depicts the triple RRR acronym and the way we conceive the kind of teachers needed to carry out the process of materials development for teacher development.

Conceptualisation

Although the expression "materials development" (Tomlinson, 1998) has different denominations in available literature, such as instructional materials design (Small, 1997), course development (Graves, 1997), course books (Harmer, 2007), instructional design strategies (Arnone, 2003), we prefer the term materials development since it offers a more inclusive definition. It embraces an array of behaviours leading to fostering effective teaching and learning settings. Moreover, it includes the adaptation and/or creation of a learning- teaching exercise, a task, an activity, a lesson, a unit, or a module composed by one or two units.

Materials development implies the combination of both reasoning and artistic processes. In this respect, Low (cited in Johnson, 1989) states that "designing appropriate materials is not a science: it is a strange mixture of imagination, insight, and analytical reasoning" (p. 153). In the same thread of thought, Maley (1998) asserts that the writer should trust "...intuition and tacit knowledge" .... "and operate with a set of variables that are raised to a conscious level only when he [she] encounters a problem and so works in a more analytical way" (pp. 220-221). Then, these authors agree on the fact that materials development entails a rational process and artistic inspiration that together perform a central role in attaining appealing teaching-learning resources.

Considering that our duty as teachers is to care for our students' learning, developing appropriate tailor-made materials that suit all of our learners' profiles becomes a fundamental must. According to Unesco (2004), "... to respond to the diversity of learners and enhance the quality of education we should improve the effectiveness of teachers, promote learning-centred methodologies, develop appropriate textbooks and learning materials, and ensure that schools are safe and healthy for all children". For this reason we insist upon the fact that developing materials embraces all teachers' attempts to create or adapt didactic resources to teach and foster students' language learning process.

Finally, Tomlinson's (1998) definition of materials development suits our perception of inclusiveness as it is "anything which is done by writers, teachers or learners to provide sources of language input and to exploit those sources in ways which maximise the likelihood of intake" (p. 2).

Principles and Strategic Components of Materials Development

As we stated before, materials development entails the blending of reasoning and artistic processes, which are guided by some tenets and essential ingredients that help both language learners assimilate and provide teachers with the groundwork to embark on the materials development route. Although in the field literature some theorists have devoted valuable time to providing principles and strategic components of materials development, such as Tomlinson (1998), Harmer (2007), Arnone (2003) and Small (1997), we will stick to Tomlinson's principles of second language acquisition (SLA) that apply to materials development. In the following list we present the tenets that materials development must hold:

- Achieve impact through novelty, variety, attractive presentation, and appealing content.

- Help learners feel at ease. SLA research has revealed that students seem to learn more and in a shorter time when relaxed and comfortably engaged in learning activities (Dulay, Burt & Krashen, 1982).

- Help learners develop self-confidence. "Relaxed and self-confident learners learn faster" (ibid).

- Be perceived as relevant and useful by the learner.

- Facilitate student self-investment, which aids the learner in making efficient use of the resources to facilitate self-discovery.

- Attain readiness, as asserted by Krashen (1985). There is a need for roughly-tuned input since it features what the learners are already familiar with, but that also contains the potential for acquiring other elements of the input which each learner might or might not be ready to learn.

- Draw learners' conscious or sub-conscious attention to linguistic features so that they become aware of a gap between a particular feature of their native or first language and the target language. Seliger (1978) suggests that helping learner notice the gap between output and input facilitates the acquisition process.

- Provide opportunities for communicative purposes in L2, thereby fostering language use, not just usage. As pointed out by Canale & Swain (1980), learners should be helped to reflect upon their existing procedural knowledge and develop strategic competence.

- Take into consideration that for learning to take place, learners may be able to rehearse certain information, to retrieve it from short term memory or to produce it when prompted by the teacher or the materials, but this does not mean that learning has taken place. Ellis (1997) reports on some research on this principle and suggests the need for post-evaluation of materials to find out what learners have eventually learned as a result of using them.

- Take into account students' different learning styles such as visual, auditory, kinaesthetic, analytic, experiential, global, dependent, independent, etc., as suggested by Tomlinson (1998) and Harmer (2007).

- Regard students' emotions or affective screen. As Dulay, Burt & Krashen (1982) assure, learner's individual motives, emotions, and attitudes are displayed in the EFL classroom, and result in different learning rates and grades.

- Allow for a silent period at the onset of instruction until learners have gained sufficient exposure to the target language and confidence in understanding it.

- Stimulate left and right brain lateralization through intellectual, aesthetic and emotional involvement. While the left side of our brain processes speech, analysis, time, and sequence, and recognizes letters, numbers, and words, the right side processes creativity patterns, spatial awareness, and context, and recognizes faces, places, and objects, as affirmed by Tomlinson (1998) and Arnone (2003).

- Offer plenty of free practice. As Ellis (1990) asserts, controlled practice seems to have little long-term effect on the accuracy required to perform new structures. Ellis also points out that control practice has little effect on fluency.

- Provide opportunities for outcome feedback. The following aspect we would like to address has to do with the fundamental elements that must be taken into consideration for the development of teaching and learning materials.

Essential Components in the Process of Creating and Adapting Didactic Learning Materials

Given that our intention is to encourage EFL/ ESL teachers to make the most of their creativity and engage them in developing their own teaching materials, we place special attention on the components that lead us along the captivating path to materials development.

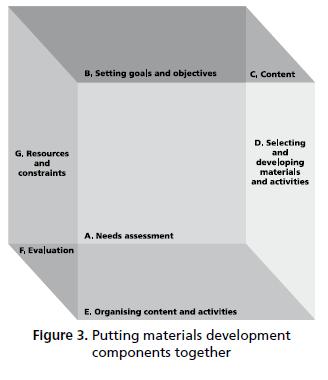

In this respect, Graves (1997) provides us with a particularly interesting framework for course development that is not one of equal and sequential parts, but rather one in which each individual's context determines the processes that need more time and attention. According to her, a framework of components is useful because it constitutes an "organized way of conceiving a complex process", explains areas of interest for teachers or "domains of inquiry", raises issues for teachers to explore and discover, and provides an array of "terms currently used in course development" (p. 12).

Figure 3 presents the way we conceive the seven essential components that make up the framework for materials development in a solid unit, integrating all of them and setting needs assessment as its core.

A. Needs Assessment

A central ingredient for developing materials is the use of systematised needs assessment procedures because it involves a set of aspects that determines teacher-decision making that will most probably help both students and teachers achieve meaningful and effective teaching and learning settings. In regard to this process, Núñez & Téllez (2008) state that as teachers most frequently make decisions regarding aims, strategies, and materials that will influence their classes, those ought to be based on a systematic well-informed needs assessment.

The previous concerns have led us to propose needs assessment as the core and, thus, the onset of materials development. In the same thread of thought, Pineda (2001) asserts that it ought to be the point of departure to make academic decisions such as syllabi development, instructional strategies and materials selection, as well as assessment and evaluation implementation. Therefore, identifying, addressing, and meeting students' needs will most probably narrow the gap between learners' needs and teaching materials that address such needs and, so, foster both their level of involvement in classroom and their language performance.

Having stated the importance of needs assessment, we can now turn our attention to what it entails. According to Graves (1997), it is an ongoing or evolving process that looks into "what the learners know, and can do, and what they need to learn or do..." (p. 12). Furthermore, it is influenced by a series of aspects such as the teachers' views of what the course is about; the situational constraints; the students' perceptions of what is being asked or expected of them; and teachers' views or perceptions of their students' needs as a result of prior contact with their students.

As we can see, carrying out a needs assessment goes beyond recognizing students' lacks. It implies making informed academic decisions that will, in turn, enable teachers to envision alternative learning routes to meet different needs, teaching environments, and students' profiles. In other words, implementing the needs assessment process will allow for more meaningful, dynamic, challenging, enjoyable, and effective learning settings.

B. Setting Goals and Objectives

Another significant aspect that must be dealt with when developing materials is the setting of learning goals and objectives. The horizon to be focused on in the EFL classroom should be set up clearly, aiming at satisfying students' needs and expectations through the development and implementation of learning materials. In this respect, Graves (1997) defines goals as the general or overall long-term purposes of a course and objectives as the specific form in which goals will be attained. They are just "particular ways of formulating or stating content and activities" (Nunan, 1988, p. 60).

Reflecting upon the reasons to set goals and objectives, we may encounter the following. First, they give a sense of direction and content framework for teachers in regard to course planning. Second, they compose a map of the territory to be explored in which the destination is made up by the goals; and the objectives by the various points of the path to go along. Third, they help teachers determine the appropriate content and activities for the course. Fourth, they help students to become aware of what they are doing in the course.

All in all, stating learning goals and objectives prior to developing materials not only gives a sense of direction of the lesson or course, but also benefits the agents involved in the teaching and learning endeavours to the degree that students undergo a successful non- threatening learning process and teachers improve their teaching practice.

C. Conceptualising Content / Designing a Syllabus

This third component encompasses the incorporation of language aspects and language learning development procedures that are vital to the course progress. Even though the definition of a syllabus seems quite simple, its design demands accurate knowledge of the teaching and learning processes. Etymologically speaking, a syllabus means a "label" or "table"; and Altman & Cashin (1992) pinpoint that a syllabus aims at communicating to students what the course intends to be, the reasons for teaching it, its destination, and the requirements to pass it. However, following Graves' description (1997), a syllabus can be considered a complex living entity under permanent change because there is never a perfect version of a syllabus, but rather one in which four focal points, namely, the language view, the learning and the learners' focus as well as the social context factor, play a central role.

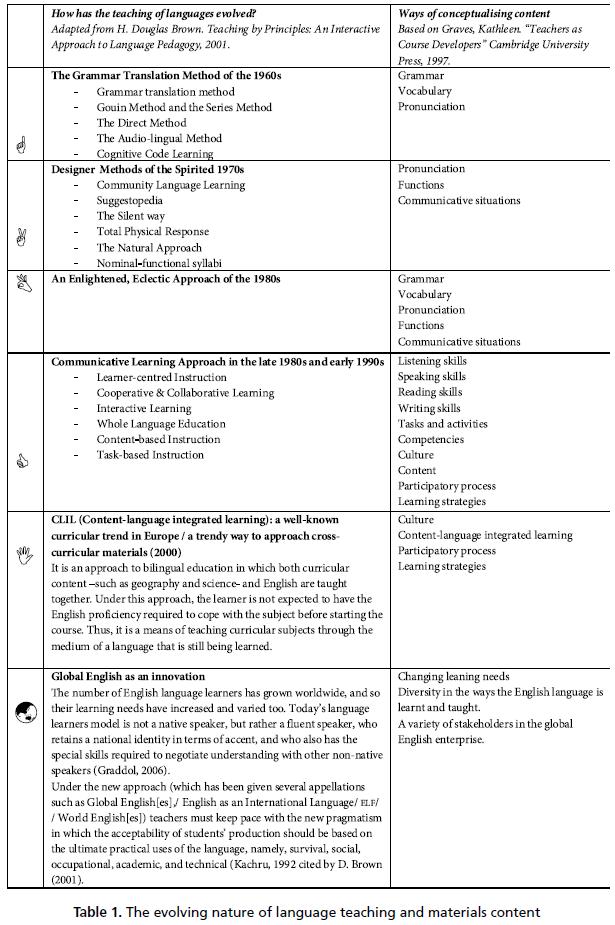

The previous reasons lead us to affirm that we cannot refer to the evolution of course and materials content conceptualisations without considering the changes that, throughout history, have taken place in teaching methods and approaches, language acquisitions insights, and educational milieus. They have, to a great extent, permeated materials production starting with the structural view of language, then moving forward to a four-skill based language approach, later to a more communicative use of the target language, and finally to the development of cognitive, communicative and contextual competencies. All these adjustments have allowed for self-directed learning, cultural knowledge and awareness, and global communication, as can be observed in Table 1.

To conclude, we acknowledge that designing a syllabus demands the integration of an array of aspects that are fundamental to language learning and acquisition within a diversity of social contexts. Indeed, learners' particular needs, informed teaching and learning tendencies, and the wide range of socio-cultural conditions must be properly identified, addressed and considered if we want to promote more interesting, significant, and favourable learning environments.

Table 1 depicts the close relationship between the evolution of the teaching of languages and the ways in which content is conceptualised.

D. Selecting and Developing Materials and Activities

Selecting materials and activities for our students is not a haphazard decision; it is one that embraces making effective and opportune decisions for their benefit. That is why we utterly agree with Graves (1997) who had the conception that any text by itself is not the course, but rather a tool that can be divided or cut up into components and then rearranged so as to suit the needs, abilities, interest, and expectations of the students comprising a course. Therefore, textbooks can be modified to incorporate activities that encourage students and move them beyond the constraints of the textbook.

In fact, a proper selection of activities must consider a range of factors such as usefulness in attaining the course purpose; suitability of students' age, interests, needs and expectations; availability of use; and plausibility of being adjusted up or down according to students' particular learning styles. Ideally, learners should be exposed to a set of carefully planned, graded, sequenced and very well-articulated learning activities that will eventually enhance students' self-confidence and self-worth as a result of learning at their own pace and in their own styles. Moreover, an appropriate selection of activities will simultaneously allow teachers to make autonomous opportune decisions that foster a harmonious and efficient development of their classes and the attainment of students' learning objectives.

E. Organisation of Content and Activities

In materials development, both content and activities could be structured in three distinct fashions known as the building, the recycling, and the sequence and matrix approaches. The first one gradually moves from the simplest to the most complex activities, from the general to the specific ones, and from the concrete to the abstract. The second one provides students with a learning challenge in terms of a new skill area, a different type of activity, or new focus. The third one follows a consistent sequence to be fulfilled within a given period.

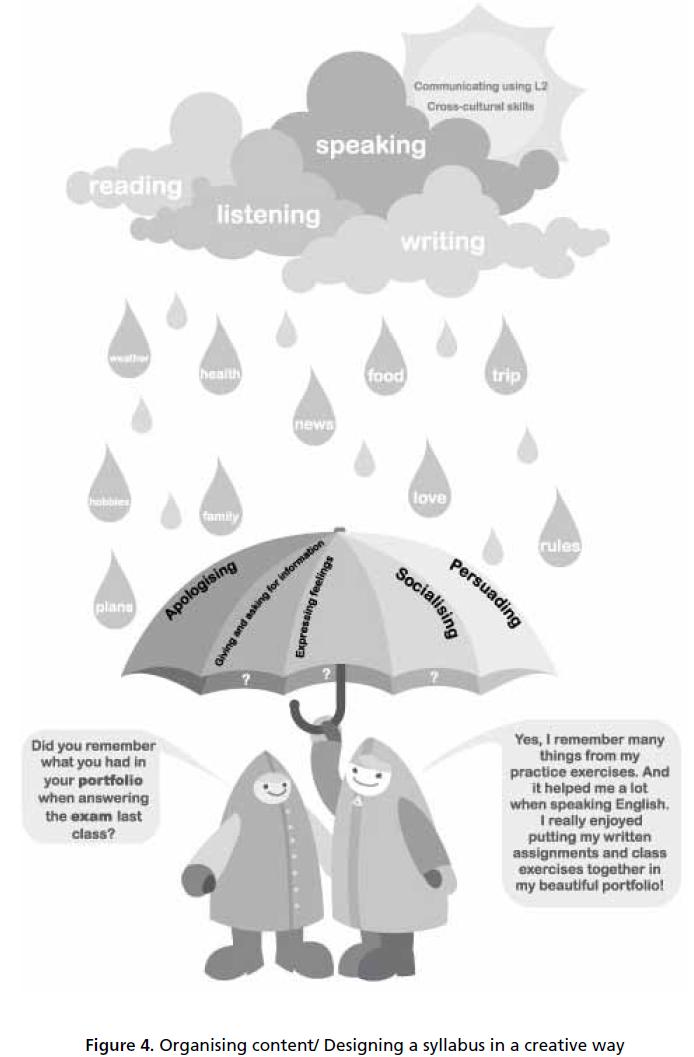

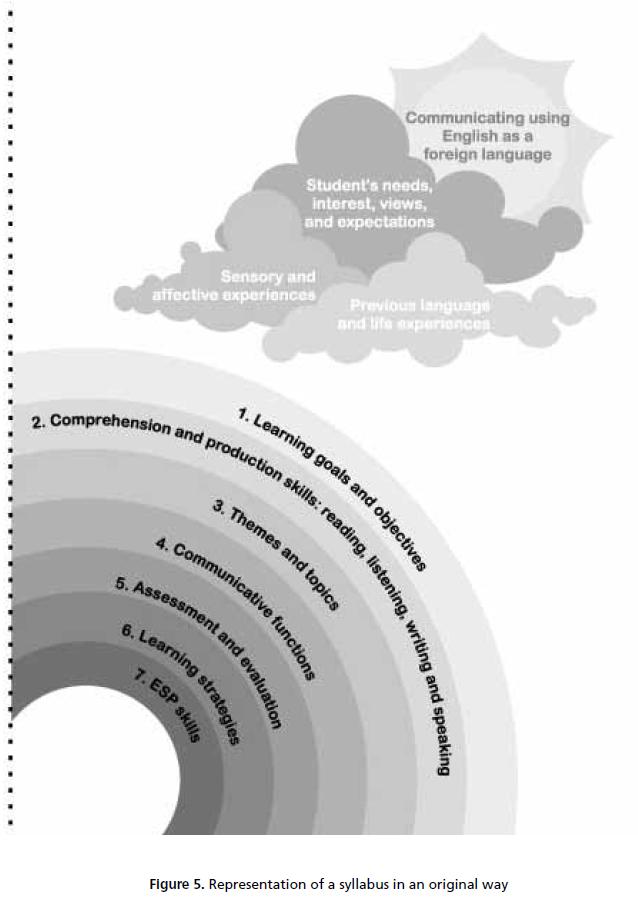

Although tables and webs are excellent tools to organise content, any graphic representation or illustration can be useful. Teachers' creativity can easily represent content and activities through a rainbow, a racing route, a landscape, etc., as can be seen in Illustrations 1 and 2. The first one is based on Graves (1997), the second one was inspired by our students' ideas about an English programme that promotes the multidimensional approach of learning a language, and English for General Purposes (EGP) and English for Specific Purposes (ESP) as its main components. Illustration 1 is an adapted version of Denise Maksail-Fine's second mind map for a high school Spanish course, as cited by Graves (1997, p. 61).

F. Evaluation

As it is widely-known, evaluation is a constant process and so must be carried out during the ongoing lessons. This suggests that any moment is opportune for the teacher to check what students have understood and how much they have been able to apply. According to Hughes (1989), evaluation is a permanent component of the course development process that serves, among other purposes, to diagnose specific strengths and weaknesses, and assess students' achievement in a course programme. However, our duty as teachers-facilitators is to make the evaluation time a positive experience that brings out the best in students, and thus builds their confidence in the process of learning a language.

Furthermore, Brown (cited in Johnson, 1989) identifies two types of evaluation: formative and summative. The former takes place during the implementation of the course and provides information about students' achievements and shortcomings and the extent to which needs are met, aiming at adjusting it while being developed. The latter, on the contrary, occurs at the end of a course and gives information about both students' overall achievement and the effectiveness of the course for future implementation. Thus, the evaluations we implement may lead students to become aware of strategy use, which, in that case, would enable them to polish up their positive language learning aspects and tackle those harmful ones as well as self-regulate their own learning endeavours.

For the previous reasons, the assessment component of the framework for materials development plays a vital role in assessing both students' needs and learning, and the course per se. In Graves' view (1997), there is a match between assessing students' learning and evaluating the course itself because the first gives a clear account of the second one and vice versa. Hence, to develop criteria for assessment, teachers should undergo the disciplined processes of formulating goals and objectives, designing a syllabus and conceptualising content.

Overall, teachers are to fulfil the dual process of stating goals and objectives, and asking students questions at both the beginning and the end of each unit, which will help them make decisions about skills and topics to be assessed, and identify what students know and what they need to refine. Thus, pre-and post-reflective questions about the materials allow teachers to detect flaws and so reexamine students' needs, reorganise syllabuses, reselect activities aimed at meeting and challenging students' needs and learning.

G. Resources and Constraints

Teachers ought to be resourceful and then adapt to the tangible or intangible givens and lacks of their teaching situation insofar as it allows them to make down-to-earth sense of all the processes involved in developing materials. Graves (1997) highlights how resourceful teachers can become in the absence of physical or technological resources, such as a classroom, books, technology, time, and even furniture. In other words, the lack of physical resources may encourage teachers to use available resources like brief periods of time or poor facilities in creative ways.

Conclusions

Our aim is to inspire EFL/ESL teachers to take advantage of their knowledge and creativity to undertake the development of their own teaching materials. Although course and materials development, like teaching, is a complex multidimensional process, all teachers are potential materials devel opers. Such process demands the careful fulfilment of a well-informed framework of components, which will eventually allow both teachers and students to succeed.

The degree of acceptance by learners that teaching materials have may vary greatly according to the novelty, variety, presentation and content used in them. The material content is likely to reach its purpose when the input in the target language the learners are exposed to can somehow be understood, inferred or deduced by the learner.

Teacher-developed materials boost not only effective learning settings and outcomes, but also teachers' pedagogical practice/performance. On the one hand, students' self-confidence and selfworth will be enhanced as a result of learning at their own pace, in their own styles, and in an enjoyable, non-threatening atmosphere that will keep their motivation up. On the other hand, opportune teachers' decision-making will foster a harmonious and efficient development of their classes and the accomplishment of students' learning objectives.

Effective materials make learners feel comfortable and confident because both the content and type of activities are perceived by them as significant and practical to their lives. However, the teaching materials by themselves are not sufficient to create effective teaching and learning settings since a lively EFL/ESL classroom depends largely on good materials used in creative and resourceful ways. Therefore, in the materials designed, language teachers need to lead their students to have materials interact appropriately with their needs and interests in order to facilitate learning.

Apart from the aspects mentioned above, materials development contributes directly to teachers' professional growth insofar as it betters their knowledge, skills and creativity, raises their consciousness as regards teaching and learning procedures, and allows them to act as agents of permanent change. This, in turn, may probably encourage language teachers to run the risk of designing materials and becoming more assertive individuals because as Marie Curie stated: "Nothing in life is to be feared. It is only to be understood." By the same token, Einstein wrote "Don't be afraid to encounter risks. It is by taking chances that we learn to be brave." In other words, it is by doing that we enhance our expertise.

Last, but by no means least, we would like to leave you with this remark to keep in mind: designing materials is not a race, but rather a peaceful journey to be savoured each point along the path, each step of the route to be travelled.

References

Altman, H. B., & Cashin, W. E. (1992). Writing a Syllabus. Idea Paper, 27. Manhattan: Center for Faculty Evaluation and Development, Kansas State University. [ Links ]

Arnone, M. P. (2003). Using instructional design strategies to foster curiosity. Retrieved on September 2003 from Eric Clearinghouse on Information and Technology, Syracuse, NY. ERIC Identifier: ED479842 Web site: http://www.ericdigests.org/2004-3/foster.html [ Links ]

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. MA: Addison Wesley Longman Inc. [ Links ]

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Curie, M. (nd). BrainyQuote. Retrieved on September 15, 2008 from Web site: http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/m/marie_curie.html [ Links ]

Dulay, H., Burt, M., & Krashen, S. (1982). Language two. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Einstein, A. (nd). Famous quotes and authors. Retrieved September 15, 2008 from Web site: http://www.famousquotesandauthors.com/topics/risks_quotes.html [ Links ]

Ellis, R. (1997). Second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Gardner, H. (1993). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Graddol, D. (2006). English next - Part three: Conclusions and policy implications. London: British Council. [ Links ]

Graves, K. (1997). Teachers as course developers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hughes, A. (1989). Testing for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Harmer, J. (2007). How to teach English-New edition. Pearson Longman. [ Links ]

Johnson, R. K. (1989). The second language curriculum. In Appropriate design: The internal organisation of course units. Chapter 9. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Krashen, S. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Nunan, D. (1988). Syllabus design. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Núñez, A., & Téllez, M. (2008, January-December). Meeting students' needs. Enletawa Journal, 1, 65-68. [ Links ]

Oxford, R. (1997). Language learning-Strategies: What every teacher should know. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers. [ Links ]

Pineda, C. (2001). Developing an English as a foreign language curriculum: The need for an articulated framework. Colombian Applied Linguistics, 3(1), 6-20. [ Links ]

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner. London: Temple Smith. [ Links ]

Schön, D. (1987). Education for the reflective practitioner. London: RIBA Publications. [ Links ]

Seliger, H. (1978). Implications of a multiple critical period hypothesis for second language learning. In W. Ritchie (Ed.), Second language acquisition research (pp.11-19). New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Tomlinson, B. (1998). Materials development in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Tosta, A. L. (2001). Laugh and learn: Thinking over the "funny teacher myth". English Teaching Forum, 39(1), 26-28. [ Links ]

Unesco, (2004). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved on September 22, 2008, from UNESCO Web site: http://portal.unesco.org/education/fr/ev.php-URL_ID=11891&URL_ DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html [ Links ]

Von Goethe, J. W. (nd). Think exist. Retrieved on September 15, 2008 from Web site: http://en.thinkexist.com/quotes/Johann_Wolfgang_von_Goethe/ [ Links ]

Small, R. (1997). Motivation in instructional design. Eric Clearinghouse on Information and Technology, Syracuse, NY. 1997 ED409895. Retrieved on September 22, 2008 from Web site: http://ils.unc.edu/daniel/214/MotivationSmall.html [ Links ]

Astrid Núñez Pardo is a full-time professor, English Programme coordinator, researcher and materials designer in the School of Education, Universidad Externado de Colombia. She holds an m.a. in Education, a Specialization in International Economics, and a b.a. in Hotel and Tourism Business Management from Universidad Externado de Colombia; and a postgraduate Diploma in Linguistic Studies from University of Essex, Colchester, England. She is author of several textbooks and Grupo Editorial Norma - Greenwich elt Editor.

María Fernanda Téllez Téllez is a full-time professor, English teacher-researcher and materials designer in the School of Education, Universidad Externado de Colombia. She holds an m.a. in Education, Universidad Externado de Colombia, and a b.a. in Teaching Modern Languages, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá. She is also author of the book You Too Teacher's Guide for grade 7th and Grupo Editorial Norma - Greenwich elt Editor.