Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.12 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2010

The Role of Music in Young Learners' Oral Production in English

El papel de la música en la producción oral en inglés de niños y jóvenes

Daniel Fernando Pérez Niño

Universidad Nacional de Colombia, sede Bogotá

dfperezn@unal.edu.co

This article was received on July 30, 2009 and accepted on January 13, 2010. This article reports on a study conducted at Universidad Nacional de Colombia in the foreign language extension courses. The author shows how young learners who study English in this program can develop their oral production by making and listening to music. The study took place in the first semester of 2009 and followed the qualitative and descriptive approaches to classroom research. The author describes how young learners view music as a ludic tool that will improve their oral performance and how the activities applied by a music teacher help to reinforce the language topics studied in other English classes. Key words: Music in English learning, teaching young learners, oral production Este artículo reseña un estudio realizado en la Universidad Nacional de Colombia en los cursos de extensión de lenguas extranjeras. El autor muestra como los niños y jóvenes que estudian inglés en este programa pueden desarrollar su producción oral creando y escuchando música. El estudio se realizo en el primer semestre del 2009 y siguió los enfoques cualitativo y descriptivo para la investigación en el aula. El autor describe como perciben los niños y jóvenes la música como una herramienta lúdica para mejorar su desempeño oral y como las actividades musicales que realiza un profesor de música ayudan a reforzar los temas estudiados en otras clases de inglés. Palabras clave: la música en el aprendizaje del inglés, enseñanza del inglés a niños y jóvenes, producción oral Introduction

Learning is a long process which depends not only on the inner abilities of the student, but also on the method chosen for teaching any subject. Although Gardner (1993) in his theory about multiple intelligences said that there are many different ways of learning, we have to take into account our methodology and how we use other disciplines in order to make the learning process easier.

Learning an alternative language is different from learning any other kind of subject. This is the conclusion that I came to after studying English for almost five years. It is different in the sense that you do not learn just structures and vocabulary. While you are learning a foreign language, you are learning the culture behind that language and you are learning thousands of years of history. In other words, you are acquiring a different way of thinking.

As a language student (in this case English student) I have to say that learning by doing is the best way to learn the components of English. Ludic activities and games are useful to apply what you learn in a specific context; however, there is another way of teaching English. You can use alternative disciplines in order to teach the language components already mentioned. Some language teachers use science or theater for teaching English or French, but others use music for the same purpose. It was interesting for me to see how music could be applied in the theories of teaching language and how students reacted when learning a language using this discipline. I felt interested in examining how a teacher could apply different alternatives for reinforcing the information we are teaching. Hence, being a close observer helped me to see how music was really attached to English learning each time I was in the classroom.

The following sections present the problem, the research questions and the main participants of this project; then, the theoretical framework and the methodology are explained. We bear in mind the theories about music, learning during youth, oral production and the data collection procedures, respectively. Finally, the results, the conclusions and the recommendations to be taken into account for future studies are included.

The Problem

One thing that we as language researchers have to keep in mind is how we teach a foreign language. We cannot follow the traditional way in which the teacher is in front of her/his students, writing several structures on the blackboard. This is the typical method used in elementary and high schools, and that is why in most of these places there is a low level of English proficiency.

Teaching a foreign language is not just about teaching structures; this is only one step of a big process. You have to create real language use for your students by taking into account the context in which you are involved.

As a result of the interest generated by the methodology used in the extension courses for children, I took into account the following research questions in my project:

- What kind of music was the teacher keeping in mind? In other words, what specific kind of music did the teacher use in order to teach the English class. Did the teacher use musical instruments for students to make their own music? Or did the teacher use common songs?

- What kind of activities did the teacher plan for teaching the English class? In other words, did s/he apply ludic games, role-plays or other kinds of activities related to music?

- How did young learners react when they took the specialized English class?

- How can other pedagogical alternatives like music encourage and reinforce the speaking ability of young students?

Research Setting and Participants

The context in which this research project was involved corresponded to one of the foreign languages extension courses developed by the Foreign Languages Department of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogotá. The methodology of these courses was that each one of the courses had two teachers: the first one, which was called the regular, had to teach the basics of English language. The main job of the regular teacher was to teach and to work with students on the main skills: listening, speaking, reading, writing and grammar, according to the expected proficiency level; and the second one, who was called the specialized teacher, had to reinforce those skills and teach a different discipline.

There were specialized teachers who taught the students certain basics according to the discipline in which the teacher was working. Some teachers worked on painting and drawing, and taught the students how to create pieces of art. Also, there were specialized biology teachers, who taught the students how to do experiments in chemistry. Other teachers specialized in physical education and gave the students the opportunity of jogging, jumping, playing soccer, basketball, volleyball or others. Finally, there were specialized teachers in music, who taught the English language by using musical instruments, by having the students sing and engage in other activities.

Knowing that it was a six months' course, the music teacher divided the course program into two main parts. The first part was called theoretical feedback, because the teacher focused on teaching specific vocabulary and the characteristics of each one of the main musical instruments. It did not mean that the class was boring. Instead, the teacher encouraged ludic activities to make the class more pleasant. On the other hand, in the second part –called practice and reinforcing– the children could practice what they learned in the first part by playing musical instruments.

The participants who took part in my investigation were students from 10 to 15 years old. They were part of one group called Seekers Challengers who took classes in the Extension Courses of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, in Bogotá. These children took three English classes: two classes with their regular teachers and the last one with their specialized music teacher.

Theoretical Framework

Being a language teacher is a hard job if we keep in mind that we are trying to get the student to acquire a new and different language. Hence, it is helpful to find some other pedagogical tools in order make our work more effective. Here we have some theories and other studies related to the role music plays in young learners' oral production

Music as an Alternative Method

The use of alternative pedagogical methods in learning processes is not anything new in foreign language acquisition. Music is a subject that has been used in this field as a teaching tool for many years. It has been demonstrated that music is a trigger that improves academic skills such as vocabulary and grammar, and also develops linguistic abilities (Jalongo & Bromley, 1984; McCarthy, 1985; Martin, 1983; Mitchell, 1983; Jolly, 1975). As a ludic activity, music is a discipline that not only reinforces such mentioned abilities but acts as a great motivational source that helps teachers to make the class enjoyable.

The role of music for Catterall (2006) has to do especially with the cognitive abilities that the learner can improve by keeping in mind musical concepts such as songs or instrumental music and how these can improve learners' special reasoning. This is, in turn, connected with subjects like mathematics, language skills of writing and reading and, finally, verbal competence. In the case of language development, the relationship is somehow more indirect, but at the same time important: what we write, what we read, and what we hear involve words that are used and understood in specific contexts. These contexts can be seen as spatial networks involving words with related words, words with their historical backgrounds, words with their social relationships, and words placed in expressions.

In addition, in a study carried out in Colombia, Morales (2007, p. 163) stresses that "While listening to a song we can read the lyrics and clarify pronunciation issues, we can sing and practice speaking and pronunciation skills, and we can write opinions or answer questions about our understanding of the songs". These kinds of listening activities, apart from being a good teaching and learning alternative, are useful and effective for language learning.

Nowadays, music is used as an important pedagogical tool, especially in English as a Second Language (ESL) in both young learners' and adult classrooms. It is useful for creating enjoyable environments as well as for building listening comprehension, speaking, reading, and writing skills; it is also useful to increase vocabulary and to expand cultural knowledge. As pointed out by Lems (2001), songs contextually introduce the features of supra segmentals (how rhythm, stress, and intonation affect the pronunciation of English in context). Through songs, students discover the natural stretching and compacting of the stream of English.

Young Learners

By young learners, we understand the ranges in age from 11/12 to 17/18. This is a stage in which it is difficult to say whether the person is a child or an adult. According to Laza (2005), there are some physical changes that affect not only students' learning, but also their personality. Such changes have to be underlined and analyzed as important learning factors. Those physical changes start and continue from 10/11 years of age to 16/18 in boys; in girls this process goes from 10/11 to 14/18. We, as the teachers of young learners, have to be careful and alert to be able to deal with the physical and emotional changes.

Referring to personality, it is relevant to talk about the personality and identity development of young learners. This is the period in which teenagers have to adopt their own way of thinking, their own values and identity. There is heavy social pressure on them. Self-esteem is the key word at this stage. If we as emotional supporters do not inculcate in them this essential concept, we will later on have behavior problems in the classroom and in the home.

Social tradition has some beliefs about children and their ability to learn a second language effortlessly, superior than the adults' learning ability. According to Brown (1994), it happens because of children's amazingly widespread success in acquiring other languages. They exercise a good deal of two important mental skills: cognitive and affective effort for internalizing languages. The main difference between children and adults, apart from their ages, is the contrast between the child's spontaneous, peripheral attention to language forms and the adult's overt, focal awareness and attention to those forms.

Oral Production

According to Guerrero (2004), when foreign language learners try to speak, the accuracy of their speech, the variety and precision of their words and the complexity of their utterances are highly influenced by some specific factors such as the anxiety that learners feel as they speak, the degree of cognitive complexity of the task that they are trying to perform, and their proficiency level. As we can see, these factors are relevant if we are going to analyze the oral production of young learners, even that of children who are acquiring their oral skills.

Some investigators like Levelt (1989; 1993) have suggested that the production system can be broken into a number of distinct components which have specific functions such as finding and organizing the concepts of a message or articulating it into sounds and utterances.

Bearing in mind one of the investigations about oral interaction developed by Cazden (1988), Hall & Verplaetse (2000), language classrooms can be seen as sociolinguistic environments and discourse communities in which interaction is believed to contribute to learners' language development. According to the aforementioned authors, oral production has to do with the transfer of meaning. In oral production, people learn the foreign language grammar structure and connect its structures with oral ability, pronunciation and sound patterns.

In another study conducted in an English class of the Extension Program of the same university where the present investigation took place, Monsalve & Correal (2006) examined the development of children's oral communication in English and the way in which the activities and the teachers' roles created or expanded students' opportunities for learning. The study revealed that children's oral production was possible thanks to the teacher's efforts to provide children with topics and activities closely related to the students' particular interests and needs. Likewise, the teacher created an appropriate learning environment in which children were challenged to use English in meaningful ways.

Research Methodology

This study followed the descriptive research approach. According to Knupfer (2007), the descriptive approach provides a detailed account in connection to the type of research question, design, and data analysis that is applied to a given topic. It does not fit neatly into either quantitative or qualitative research methodologies because it uses elements of both. In addition, it uses descriptive statistics, which refer to what is. In contrast, inferential statistics try to determine cause and effect.

In order to gather the information needed for this study, I used field notes, diaries, video recordings and interviews.

Based on Cohen & Manion (1994) and Burns (1999), I used observation because through it we can abstract real data from real situations. By using observation you can analyze and study the environments that data come from. In other words, through observation we can describe perfectly not only the features of participants, but also the context to which the participant belongs.

Field notes are one of the best observational data techniques because it has observation as the most important complement. Notes help the researcher to register some specific facts about their participants at a specific moment. My expectation was to use notes as a primary way of collecting the basic data when the music class was taught.

The diary, like notes, also belongs to observational techniques or, according to Nunan (1992), introspective methods. Diaries are very similar to notes in terms of the observational component; however, this technique is more systematic and has a specific structure in terms of order. In diaries, you can write the important facts that you are seeing and give those a detailed order by date or by time of occurrence. Diaries helped me record relevant events observed in class and consolidate information that was also collected through other instruments. In other words, the diary was more linked to the personal notes that I, as the researcher, wrote about the class management and methodology applied by the teacher.

Video, as well as audio recordings, provides us with denser linguistic information than does field note taking for, ideally, it allows us to record every word. When taking field notes, the researcher is limited to writing down the gist of what the interlocutors said, or recording only brief interactions consisting of a few short turns because of constraints on memory and the inherently slower speed of writing as compared with speaking (Beebe & Takahashi, 1989). Recordings were the main instrument that I used during the project. Through these, I could describe each one of the activities applied by the music teacher. First of all, I chose three classes in which music had more of a presence, then I recorded five lessons altogether, as well as the students' perceptions, as expressed in the interviews I carried out. Finally, I transcribed the data collected in order to find the results.

Interviews are an elicitation or non-observational technique which allows the researcher to obtain more in-depth information. Most effective interviews require researchers to develop a guide to use during the interview process. Thus, it is important to follow certain guidelines and to train all interviewers to use the same techniques. In order to apply the interviews, I bore in mind the recommendations pointed out by Siedman (1998):

- Listen more, talk less

- Follow up on what participants say

- Ask questions when you do not understand

- Ask to hear more about a subject

- Explore, do not probe

- Avoid leading questions

- Ask open ended questions

- Follow up, do not interrupt

- Ask participant to talk to you as if you were someone else.

Some personal interviews promote a higher response rate but require more staff, time, and travel. I interviewed the music teacher in order to get a professional opinion about the presence of music in English learning (see Appendix 1). It was also important for me to know how students felt in each class, so I interviewed them (see Appendix 2)1. I picked the last classes for interviewing them because it was at that time when the teacher and the students had a clear image about music and the English language.

Data Collection Process and Analysis

As already mentioned, the field notes and the video recordings were gathered inside the classroom. The diary contained additional reflections and some other observations registered after the specialized class. In addition, the interviews reinforced the information that I collected through recordings and notes and gave me a different perspective of the situation despite the subjective content of each one of the interviews I did.

When the specialized English classes started, I focused on five classes in which I applied the data collecting instruments. In the process of analyzing data, my units of analysis were the evidence of children's oral production collected through my journal and the transcriptions of the audio and video recordings. Some information such as the teacher's and students' experiences, as well as impressions and opinions were also useful for me as a means to complement my understanding of the phenomenon under study and to ensure data validation.

In terms of qualitative data analysis, which was the option adopted in this study, González (2004) explains how qualitative information must be organized and classified. He stresses that qualitative data is linked to content analysis.

Results

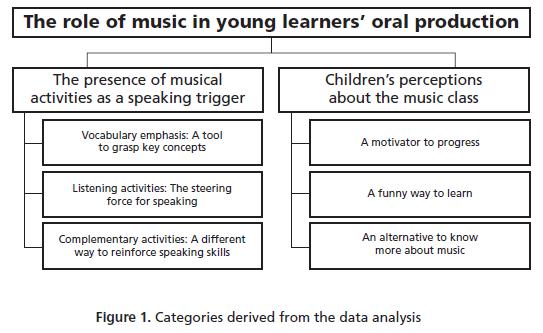

On the basis of the research process described before, and following González (2004), I categorized, codified and interpreted what I grasped from the classroom. Diagram 1 depicts the categories and subcategories found in the study

The Presence of Musical Activities as a Speaking Trigger

This is the category that embraces a set of facts that helped children speak in class. What follows is an explanation of the kind of activities the English music teacher used for encouraging children's oral production. To do so, it was divided into three subcategories, each one of them linked to the actions in class and how they affected the children's oral production. Now let's examine each one of the subcategories in detail.

Vocabulary Emphasis:

A Tool to Grasp Key Concepts

I noticed that one particular aspect of the several exercises that the teacher prepared for kids was that all of them focused on teaching children specific vocabulary related to music. In other words, the main emphasis of this specialized class was vocabulary learning and listening comprehension, as evidenced in the following extract:

T: (...) Well, according to all the activities I plan every Saturday for children, there is no doubt that my two most important emphases are vocabulary and listening... Because it is a music class, it's important for them first, to train their ears with songs with advanced vocabulary and second, to have the specific concepts about music and the knowledge of some musical instruments that I am showing for them. (Teacher's interview, April 18, 2009)

The interview let me know about the emphasis that the teacher proposed for the lessons. It was also important to analyze in detail the activities that he planned in order for the children to grasp specific vocabulary and key aspects that helped them with musical knowledge such as instruments and their characteristics. The following extract illustrates how the teacher went about it:

The teacher asks student to read the first part of the lesson prepared for this day in order to get them interested in music theory.

T: Ok, guys, this is the first thing we are going to learn in the first music class. Do you know the difference between sound and noise?

C: [Noise]... Umm... No teacher

T: So... Let me see... You please read the first part!

C: Sound without definition is called... noise. For example, a broken glass or car crash. (Journal, February 21, 2009)

This example shows that in this music class, the teacher had students identify vocabulary by asking them for the word noise, a key concept, and by having them read what noise means. These kinds of exercises helped children not only grasp words or definitions, but also involved other skills such as reading.

Listening Activities:

The Steering Force for Speaking

In connection to this category, we should highlight the kind of listening activities the teacher used in class. The teacher used listening activities such as common songs with authentic English in use and musical instrument sounds to get children to recognize the instrument they were talking about. I noticed that both of them are used in class, first, for teaching them vocabulary and, second, for supporting the speaking part.

During the data collecting process, I wondered about the type of music they listened to in class. I was surprised when I came into the classroom to observe them. Below, we can read the events that took place at the beginning of a lesson I recorded:

The teacher plays a song and all children pay attention. While the song is playing, teacher guides children with numbers, so they can catch the missing word and fill in the blank. When they finished the children seemed very interested and asked the teacher about unknown words.

C: Teacher, what's the meaning of dar...kness?

T: Ok, for example, when you go to sleep and you turn the lights off, so what happens.

C: Eee... queda oscuro. [It gets dark.]

T: So, what is the meaning of darkness?

C: Ahh... 'Oscuridad' [darkness], and teacher, what's the meaning of bones?

T: It's what you have in your body, so when you touch it, is hard and white

C: .Huesos? [Bones?]

T: Yes, very good, Ok, so let's see... so far... The meaning not of the unknown words but the whole meaning... So who wants to tell me the meaning of the song?

C: Umm. La cancion dice que [The song says that...]

T: Wait a second, do it, but in English please.

C: Ehh... It says that a men, no, no, a man that... thinks in aaa.. woman every time and Sunday remembers she... ehh... her.

T: So far so good, Esteban. (Transcription of a video and audio recording, March 14, 2009)

This piece of data exemplifies that these kinds of songs were used to encourage the speaking part in the music class. In most of the classes, the teacher prepared a different song for practicing the listening and the speaking part. With this kind of activities, children could, first, have a good time by relaxing with music and, second, learn some unknown words useful to them to understand the meaning of the lyrics. Finally, after doing the exercise, the teacher tried to make them talk about the song.

On the other hand, Woodall & Ziembrosk (2004) pointed out that oral language is an interactive and social process, and using songs with authentic meaning is a natural way to experience rich language in a pleasurable way. Songs are a good way for teaching children not only theoretical concepts related to music, but also vocabulary we use daily. In order to exemplify this fact, I extracted the following sample from the teacher's interview:

I: What do you expect from the listening activities you plan for children?

T: OK, first of all, I think about the development of the class, I think that songs make the class more pleasant for them and it is a good tool for teaching them vocabulary and some grammar structures. What I expect is to support of course listening and speaking when I ask for the pronunciation or the opinion about the song. (Teacher's interview, April 18, 2009)

Complementary Activities:

A Different Way to Reinforce Speaking Skills

This was an important category in my research project. Although we have seen that listening activities were the main bases of speaking outcomes, there were alternative activities that helped to reinforce not only the students' oral production, but also the other linguistic abilities. This category was made up of three subcategories which helped me identify the use and role of some complementary activities the teacher used to reinforce the speaking skill: Games such as contests and competitions in the classroom; reading and writing skills for children's speaking outcome, and visual aids for helping children speak in class.

Activities prepared by the teacher of the music class, such as contests or games were also a good connection between music and learning. Piaget's research and theory (1965) convinced constructivist educators of the value of group games for intellectual and moral development as well as for social and physical development. In most of the sessions, the teacher I observed prepared a contest in which a group of boys and a group of girls had to confront themselves. The idea of this kind of game was to practice and consolidate all the vocabulary and the topics that they had previously learned. This evidence is shown in one of the teacher's interviews, as shown in the following extract:

T: These games that I prepare represent the class environment that I want. You know, games make the children feel fine and comfortable in class, and improve the participation. That's why I try to make contests for them, not only for changing the classroom environment, but also for reinforcing all the topics I teach for them. (Teacher's interview, April 18, 2009)

Most of the contests that the teacher organized for children were intended to help children practice vocabulary about the musical instruments, their proper spelling and the perfect pronunciation of the words describing them. Children could also develop oral production by interacting with their classmates and by having a good time in class, as seen in the following example:

After the teacher's explanation of the activity, children get excited and want to start playing.

T: Ready? So, let's begin, so you will be number one, two, there, four, five, six and seven right?

C: Which number you are?

C: Seven

C: Huyy... The last one, yo vere, no se deje ganar de Natalia [I'll see... Don't let Natalia win.]

T: Ok, so number ones, please come here.

C: COME ON CAMILO, WIN, WIN, WIN, WIN...

T: OK. Silence, calm down... (Transcription of a ideo and audio recording, March 21, 2009)

The example above illustrates what the teacher explained in the interview. Children got really excited in those types of activities, no matter what kind of topic he was teaching them. This shows that if you try to make the class environment funnier, you will be able to teach them all the things you want.

Reading and writing skills for children's speaking outcome was the second sub-category found in connection to complementary activities. I want to highlight a special particularity that happened regularly in some other activities related to the interconnection of skills, especially reading, writing and speaking. It is not a new issue in language learning.

As Cárdenas (2000, p. 15) argues: "Listening comprehension is added on to established stages of reading, writing and speaking". At this point, we can say that all reading and writing activities used in the extension course under study were interconnected. They were also useful in encouraging the young learners' oral production. This can be observed in this instance:

The listening exercise ends and the teacher starts the second activity with another worksheet about string instruments.

T: You... please start reading... Esteban! Yeah... you please, start with the first part.

B: Es...tring instrument.

T: String instruments

B: Perdon [Sorry]... String instruments... the four major instru...ments in the string instruments, the violin...

T: Violin

B: Violin, the vio..la, the chello

T: Cello

B: Cello and the doub...le brass... ehh bass

T: Repeat... double bass

B: Double bass. (Transcription of a video and audio recording, March 14, 2009)

Visual aids for helping children speak in class were the third sub-category in the area of complementary activities. When the child finished reading the first part about the characteristics of the violin, the teacher got prepared for showing them the violin's image.

T: So, the violin... I think you already know this instrument! He shows a flashcard of a violinist.

T: Do you know the violin, don't you?

C: Yes...

B: As you said teacher, put the violin on the ... How do you say... .Cómo se llama? [How do you call it?]... ¡Barbilla! [Chin!]

T: The chin, you have to put the violin on the chin... and play... Do you see?... So repeat: Violin

C: VIOLIN. (Transcription of a video and audio recording, March 14, 2009)

As we can see in the example, visual aids –in this case, flashcards– helped children to grasp new information and consolidate language learning. Also, we can see how the teacher directed the lesson for practicing pronunciation, which was basically the main objective of the music teacher in most of the classes.

Flashcards were really useful for the teacher to make the learning process more effective and funny for young students. Children need to have all five senses stimulated. Sensorial inputs like the smell of flowers, the touch of plants or audiovisual aids like videos or pictures are important elements in children's language teaching (Brown, 1994). Through my experience in the practicum, I could see that images help children, first, to perceive more in detail what they are learning and, second, to grasp information faster. Below we can see an extract from the oral evaluation children had. In it, we can see the role of visual aids in oral production.

While children prepare the music folder, the teacher calls each one of them for the oral test.

T: Ok, I want here just the one who I called, the rest of you please in your place, ok? So, Maria Paula, please bring me your music folder and come here.

G: Teacher, this is the folder.

T: Ok, so let's check, one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine and ten... Very good and you have... three points for the last tournament. Now, I am gonna show you some flashcards and you are gonna tell me the name of the instrument. Ok, so, here we go.

The teacher shows Maria Paula the flashcards of the musical instruments they have seen.

G: Ehh... snare drum, cello, cymbals, umm... oboe, violin [violin], clarinet.

T: Ok you failed just one, please repeat: violin.

G: Violin.

T: Ok, so the next one, Ricardo Jose, please come here with the music folder.

B: Teacher, aquí está el folder [Here you are the folder].

T: Ok, so please check how many worksheets do you have.

B: One... seven, eight nine and ten... Ten, teacher.

T: Ok, I´m gonna show you some flashcards and you are gonna tell me the name of the instrument, ok? So get ready... The teacher shows Ricardo Jose the flashcards of the musical instruments they have seen.

B: Umm... Xilophone, violin, stream drum, oboe, cello, French horn, flute.

T: Ok Ricardo, be careful with the pronunciation, you failed two answers, please, repeat: Oboe

B: Oboe

T: And snare drum.

B: Snare drum.

T: Ok, good, Ricardo thank you. (Transcription of a video and audio recording, April 4, 2009)

Children's Perceptions about the Music Class

This category is made up of four subcategories which helped me to organize and identify the most important perceptions children had in relation to the music class they attended each Saturday. Most of this information was collected through the personal interviews I carried out with them. Children were comfortable with the interview; they expressed what they felt and thought about the class and the teacher.

The Music Class as a Motivator toward Progress

Children feel very bad when they do not understand the exercises that they have to do in class. In fact, we adult learners feel the same way when we have to face these kinds of situations. But this bad sensation helps teachers wonder about possible solutions that exist for avoiding these feelings. In the case reported in the following interview extract, a girl decided to study more to understand the activities and enjoy the class more:

I2 : Laura Carolina, how have you been in the last English classes?

G: Umm... ee... fine

I: Why did you hesitate?

G: Because at the beginning I did not like to come to class. It seemed that the activities were really difficult, besides, the teacher speaks in English all the time. It is difficult to me understand his explanations.

I: And now?

G: Now I like to come to class because I studied very hard and I already understand a little bit more.

I can do all the homework alone. (Children's interview, April 4, 2009)

Just as Laura Carolina, there were some other children who felt bad when they had to come to class because it was very hard for them to understand all the explanations that the music teacher gave them. Nonetheless, encouragement was a key factor to engage her in the class processes, as can be found in the following extract:

T: So, Laura Carolina, please... quickly, and the last one... Santiago, please, be prepared ok?

G: Teacher, I am Laura Carolina.

T: Ok so, check out how many photocopies do you have

G: I have just eight copies

T: Umm... Now, listen to me. I´m gonna play some sounds, the idea is that you have to tell me the names, clear?

G: Ok., lista [ready].The teacher plays some musical instruments' sounds...

G: Cello, violin, triangle, xylophone, snare drum, oboe, flute.

T: Ok very good pronunciation, but you have 3.9 for the two missing copies. So be careful ok?

G: Bueno profe [Fine, teacher]. (Transcription of a video and audio recording, April 4, 2009)

As Dörniey (2001) remarked, one important aspect to take into account about children's self confidence is encouragement. Now, the two extracts above, from the oral test, demonstrated that the student was able to recognize and pronounce all the names of the musical instruments. The girl also felt encouraged to continue working. On the other hand, from the responses of two girls who told me in the interviews that they could not understand what the teacher said, we can conclude that the music class was a good motivator for students to improve their language level.

Music as a Funny Way to Learn

It is common knowledge that music is a good alternative for relaxing and having fun. People in general play music while working or studying. In most cases, music can be used in the language learning field. Young children seem to be naturally "wired" for sound and rhythm (Davies, 2000). In our case, most of the children in the music class agreed that this subject could be used in language learning classrooms to make the class nicer and more pleasant. Also, through music, children can learn structures or vocabulary faster.

One aspect of this research project was to assure that music helped children to learn in a funny way. In the following excerpt we have some information that illustrates this fact:

I: Laura Valentina, Do you like music, I mean, do you like to learn English through music?

G: Yeah, yeah, I like music. I like to play the recorder and guitar... Ok. I do not play guitar so much because I am learning right now.

I: Ahhh... but do you like it?

G: I would say yeah as for English... I also like it and I think it is cool to combine the two subjects in just one class

I: why?

G: Because we can learn in a different and a great way; besides, when the teacher bring us some songs, we can sing and listen to these. (Children's nterview, March 21, 2009)

In the previous extract, we can confirm that music is a fun way to learn English because young learners enjoyed doing listening activities with popular songs. They liked to learn unknown vocabulary related to music and enjoyed bringing musical instruments to the class too. In regards to this confirmation, Griffee (1983) stated that songs can be used to encourage extensive and intensive listening, to stimulate discussion of attitude and feelings, to encourage creativity and use of imagination, to provide a relaxed classroom atmosphere, and to bring variety and fun to learning.

It should also be noted that although most children did not know how to play a musical instrument, they really had fun listening to the music and sounds. This facilitated the learning process and made the class enjoyable. In this context, if we take into account the role of specialized classes, we could say that it could also supported the other English classes as seen in the following example:

I: Do you think that specialized classes such as music, or sciences could help children to reinforce English language?

T: That's the idea. I think that the specialized learning, in this case music, is a parallel learning that makes children to have whole language learning in many subjects. Besides, the classes such as theater, science or music are very funny for them, so I think that these classes are a good tool for children to gain knowledge of English. (Teacher's interview, April 18, 2009)

The Class as an Alternative

to Know More about Music

The extension courses in the extension program under investigation have one particularity and it is that all children, from the first level, have to take a specialized course in which they are taught subjects in the arts (involving areas such as drawing, theater and music) or science. In these classes students learn how to engage in scientific experiments. In other words, apart from taking the normal English classes, they take classes in specific subjects in order to complement their language learning with some different activities. Let's read some examples which show the views of children in respect to the program organization:

I: Do you think that all specialized classes are useful in the extension courses?

G: Yes, because we can learn other subjects, for example, last year we studied science and besides we made experiments. Now that I am taking music, we can learn more things in a funny way. (Children's interview, March 21, 2009)

If we analyze the opinion of this child, we can see that students agree with the fact that it is good to have the chance to learn English by studying other subjects. Ludic activities such as playing musical instruments or making scientific experiments make the class pleasant for children. Furthermore, it is a good trigger for teaching in the sense that children enjoy the class and feel comfortable in the classroom. These views are also present in the following opinion about the music class:

I: Santiago, what things of the music class call your attention?

B: Hummmm, the fact that they are teaching us other things in English; for example that each musical instrument belongs to a specific family, the differences between sound and noise and many unknown words... What we did not know.

I: Can you learn all these things, even if the teacher speaks English all the time?

B: Mmmmm, at the beginning it was very hard because in the primary school the teacher speaks Spanish all the time, but here the things change because sometimes I do not understand what he says but little by little you get accustomed and finally you understand everything. (Children's interview, March 14, 2009)

As can be seen, there is clear evidence about the positive view of the specialized classes. Students think that the music class is a good opportunity for learning new, useful things to complement what they already know about music and about English.

Conclusions

After examining the main opinions of the students and the teacher participating in this study, we can have a clearer vision of the specialized music class in the extension courses at the University, as well as of their benefits for young learners. The findings revealed that the music employed by the teacher in the specialized class presented two features. The first feature had to do with the specific songs the music teacher exploited in class. The teacher used popular rock and pop songs in most listening activities he planned in order to promote the speaking part. As a result, children enjoyed doing listening activities like filling in the blanks and discussing the whole meaning of the songs as well as the unknown vocabulary they found. The second feature had to do with the musical instruments that the teacher used to help children grasp the specific musical concepts of the class. In other words, musical instruments were useful to explain to students some important concepts related to music such as the specific features about the appearance and sound of each one of these instruments.

Visual aids were also used to enable students to pronounce the corresponding name of the musical instruments and to have them recall or infer relevant information. In most classes, especially in the oral test session, I observed the teacher placing emphasis on the visual aids in order to evaluate the children's oral production; however, the interesting part of this activity was that the children, by looking at the image, could recognize the name of the instruments. Although a few children made mistakes, they distinguished the name of the instruments, so it made confirmed for me that visual aids are useful for oral correction.

As for the reactions or perceptions of young learners in relation to the specialized English class, I found that music sessions worked, first, as a motivator to enable students to advance in the English course. In addition, children felt confident and motivated when they heard the music teacher explaining the activities in English. It helped them to improve the English level by getting accustomed to the pronunciation and the intonation of the English language. Furthermore, music was a fun way to learn English. Children enjoyed the music class and its activities so much that they also wanted to practice more with the musical instruments. In general terms, most students agreed that the specialized music class was a fun way to grasp information and gain acknowledge.

Further Research

I want to remark on the importance of using other subjects such as music, science, or arts to teach a second language. In the National University Extension courses, children not only learn the general aspects of the language but also find the opportunity to learn it in some other contexts; in this case, in the music area.

Although there are several research studies about the link between music and learning, this investigation had some different aspects, which can add more interesting statements to the field. On the one hand, here we have a very strong link between English and music in terms of language acquisition in a very specific context and with a very specific group of participants in an extension program. On the other hand, this investigation was supported by some theories which state that music can be an excellent tool to get children to learn and reinforce the linguistic skills "reading, listening, writing, speaking and vocabulary" of a second language.

One possible study highly related to the conclusions I found would be about the emphasis on vocabulary in young students' learning. This was a particularity inside my research because of the way almost all the activities planned by the teacher were followed in order to reinforce the students' speaking skills. Therefore, I think that an investigation about the relation between vocabulary and young learners' oral production could be a good complement for this research study.

1 The interviews were conducted in Spanish to let the students express themselves freely in their mother tongue and then they were translated into English for the purpose of the research report.

2 I = Interviewer (the researcher).

References

Beebe, L. M., & Takahashi, T. (1989). Do you have a bag? Social status and patterned variation in second language acquisition. In S. M. Gass, C. Madden, D. Preston, & L. Selinker (Eds.), Variation in second language acquisition: Discourse and pragmatic (pp. 103-128). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Brown, D. (1994). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall Regents. [ Links ]

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. L. (2000). Helping students develop listening comprehension. PROFILE, Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 1, 8-16. [ Links ]

Catterall, J. S. (2006). Conversation and silence: Transfer of learning through the arts. Journal for Learning through the Arts, 1(1). Retrieved from: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/6fk8t8xp [ Links ]

Cazden, C. B. (1988). Classroom discourse. Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Cohen, L., & Manion, L. (1994). Research methods in education. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Davies, M. A. (2000). Learning... The beat goes on. Childhood Education, 76(3), 148-153. [ Links ]

Dörniey, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

González, S. P. (2004). Investigación educativa y formación del docente investigador. 2a Edicion. Cali: Universidad de Santiago de Cali. [ Links ]

Griffee, D. T. (1983). Songs in action. Hertfordshire, England: Phoenix ELT. [ Links ]

Guerrero, G. R. (2004). Task complexity and L2 narrative oral production. Barcelona: Universidad de Barcelona. [ Links ]

Hall, J. K., & Verplaetse, L. S. (2000). (Eds.), Second and foreign language learning through classroom interaction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Jalongo, M., & Bromley, K. (1984). Developing linguistic competence through song. The Reading Teacher, 37(9), 840-845. [ Links ]

Jolly, Y. (1975). The use of songs in teaching foreign languages. Modern Language Journal, 59(1), 11-14. [ Links ]

Knupfer, N. N. (2007). Descriptive research methodologies. Kansas State University. Hilary McLellan, McLellan Wyatt Digital. [ Links ]

Laza, S. (2005). Adolescentes y adultos como sujetos de aprendizaje. Mendoza: Facultad de Filosofía. Letras UNCUYO. [ Links ]

Lems, K. (2001). Using music in the adult ESL classroom. Chicago: National Louis University. [ Links ]

Levelt, W. J. M. (1989; 1993). Speaking: From intention to articulation Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Martin, M. (1983). Success! Teaching spelling with music. Academic Therapy, 18(4), 505-506. [ Links ]

McCarthy, W. (1985). Promoting language development through music. Academic Therapy, 21(2), 237-242. [ Links ]

Mitchell, M. (1983). Aerobic ESL: Variations on a total physical response theme. TESL Reporter, 16, 23-27. [ Links ]

Monsalve, S., & Correal, A. (2006). Children's oral communication: An explanatory study. PROFILE, Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 7, 131-146. [ Links ]

Morales, C. (2007). Using rock music as a teachinglearning tool. PROFILE, Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 9, 163-180. [ Links ]

Nunan, D. (1992). Research methods in language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Piaget, J. (1965). The moral judgment of the child. London: Free Press. [ Links ]

Siedman, I. (1998). Interviewing as qualitative research. New Cork: Teaching College Press. [ Links ]

Woodall, L., & Ziembroski, F. (2004). Promoting literacy through music. Retrieved November 2008 from http://www.songsforteaching.com/lb/literacymusic.htm [ Links ]

Daniel Fernando Pérez Niño holds a B.A. in Philology and Languages from Universidad Nacional de Colombia. The study reported in the article was his monograph as a requirement for his degree. He participated in the extension courses of languages as monitor and nowadays works in the extension courses as an English teacher.

Appendix 1: Protocol Used for the Interview with Teachers

Teacher Gonzalo Rubiano:

The main purpose of this interview is to know your opinion about some specific aspects founded through the previous data analysis of the research I have been developing on children's oral production in your English class.

- What can you tell me about the features of the activities you use to encourage children to speak in class?

- What role does music play in the development of the activities?

- What do you expect from these activities?

- What has been your role in the development of the music activities?

- From the development of the activities, what can you tell us about the children's oral production?

- Do you consider that children get more involved in music activities than other kind of activities?

- When do you see that children get more involved? What could be the reason for that situation?

- I would appreciate your permission to use the information I get. I clarify that your identity will be protected all the time if you want it to be.

Thanks for your help, your time and your consideration.

Appendix 2: Protocol Used to Interview the Students

- How have you felt in the music class these last Saturdays since we started extension courses?

- Do you like music, I mean, do you like to learn English through music?

- How have you felt doing the activities in the music class?

- What do you do in the music class? What kind of activities do you do in class?

- Would you change anything about the class?

- What kind of things about the music class calls your attention in comparison with the regular English class?

- Do you think that music classes are useful in the extension courses? Yes? No? Why?