Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

versión impresa ISSN 1657-0790

profile v.12 n.2 Bogotá jul./dic. 2010

The Impact of a Teacher Development Program for Strategic Reading

on EFL Teachers' Instructional Practice

El impacto de un programa de desarrollo profesional en lectura estratégica en la

práctica instruccional de docentes de inglés como lengua extranjera

Fatemeh Khonamri

Mahin Salimi

Mazandaran University, Iran

fkhonamri@yahoo.com

mahin2002000@yahoo.com

This article was received on March 1, 2010, and accepted on July 2, 2010.

Research on teacher development has been the focus of attention in recent decades. The overall aim of this study was to explore the impact of reading strategy training on high school teachers' reading instructional practices. The study was conducted in the EFL context of Iran. To meet this aim, four EFL high school teachers voluntarily took part in the study. Teachers' reading classes were observed and audio-recorded both before and after the teachers took part in a three-hour workshop on reading strategies. Drawing on data from observations, the results showed some degree of change in teachers' reading practices after their having taken part in the workshops. That is, they took a more strategic approach to the teaching of reading in their classes.

Key words: High schools, reading strategies, teacher development, innovation in ELT.

La investigación en el desarrollo profesional docente ha sido el centro de atención durante las últimas décadas. El objetivo general de este estudio fue explorar el impacto de la capacitación de profesores de secundaria en estrategias lectoras en las prácticas de enseñanza. Este estudio se realizó en el contexto del inglés como lengua extranjera en Irán. Para cumplir con este objetivo, participaron cuatro profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera de educación secundaria. Se observaron y grabaron sus clases enfocadas en lectura. Esto se hizo antes y después de participar en talleres de tres horas sobre el tema de estrategias lectoras. Los datos provenientes de las observaciones arrojaron como resultado que hubo cierto nivel de cambio en las prácticas de lectura de los profesores después de participar en los talleres. Es decir, adoptaron un enfoque más estratégico en sus clases.

Palabras clave: colegios de secundaria, estrategias de lectura, desarrollo profesional docente, innovación en la enseñanza del inglés.

Introduction

English is one of the most important subjects in many schools around the world, including in Iran. Iranian students study English for at least 7 years on average. And the main aim of teaching English as a Foreign Language, especially in high schools of Iran, is reading comprehension (Roshd, 1980). In spite of the time spent and the emphasis on reading comprehension, the majority of the Iranian learners are not equipped with the desired reading comprehension ability after graduating from high school. Among many other reasons, one can be the methodology of teaching reading in high schools (Roshd, 1980).

In high school, reading comprehension instruction is limited to the assignment of a reading passage accompanied by a number of short, multiple choice, or true/false questions relating to the passage. In this type of reading practice, which is generally known as "intensive reading procedure", short passages are given to the learners to read carefully and analyze the details. This type of reading, as Alderson and Urquhart (1984) have described, is not a reading but a language lesson. What happens in such situations is that teachers do not give instructions regarding the use of reading strategies and do not tell learners how to read more efficiently. In fact, they take it for granted that all the learners know how to read a passage strategically mainly because they already know how to read in their first language (Khonamri, 2008).

It seems that in spite of the importance of reading strategies in reading comprehension, the absence of teaching them is completely felt in high school English reading classrooms. "The effectiveness of teaching reading comprehension strategies has been the subject of over 500 studies in the last twenty five years. A common conclusion from these works points out that strategy instruction improves comprehension" (Willingham, 2006, p. 39).

Generally speaking, there are two kinds of teaching strategies in the classrooms: explicit and implicit teaching (Dole, 2000). In the early 20th century, researchers seldom thought that reading comprehension should be taught (Smith, 1986, cited in Shen, 2003). Researchers began to revisit comprehension processes in the 1980s. Under the umbrella of metacognition, researchers made huge discoveries concerning expert readers' strategies and developed the term explicit instruction (Pressely, 2000). Explicit instruction is rooted in cognitive psychology. Since the 1970s, cognitive psychology has led researchers to consider reading as an active process that involves readers' interaction with the text to produce meaning (Dole, 2000). In cognitive psychology, metacognition requires learners to use not only declarative knowledge (knowing the content) but also procedural knowledge (knowing how to use the content) and conditional knowledge (knowing when and why to use the content) (Dole, 2000). In other words, explicit reading strategy training refers to "the practices of deliberately demonstrating and bringing to learners' conscious awareness of those covert and invisible processes, understanding, knowledge, and skills over which they need to get control if they are to become effective readers" (Cambourne, 1999, p. 126).

Implicit instruction is rooted in the progressive movement, which focused on children and their experience rather than on teachers and the curriculum (Dewey, 1938; Dole, 2000). According to Dewey's view, children learn best when education focuses on their interests. Implicit approaches include whole language, language experience, literary response theory (Dole, 2000), extensive reading (Bamford & Day, 1998), and free voluntary reading (Krashen, 1995).

In this study both explicit and implicit instructions of reading strategies were the focus of the investigation. Meanwhile, to be in line with the research finding on the effectiveness of teaching reading strategies in reading comprehension and initiating the changes necessary to be brought to reading classes, teacher professional development programs were considered to be a solution. Teacher professional development or teacher learning can occur through activities like self-monitoring, journal writing, teaching, portfolios, action research, peer observation, reflection, and workshops (Richards & Farrell, 2005).Workshops are one of the most common and useful forms of professional development activities for teachers (Richards & Farrell, 2005). Thus the purpose of the present study was to explore the relation between teachers' reading classroom practices and professional development regarding reading strategies. In other words, it examined the impact of reading strategy training workshops as a professional development program on teachers' practices regarding reading strategies. To achieve the purpose of the study the following research questions were raised:

- Which reading comprehension strategies are most frequently taught by EFL high school teachers?

- Is there any change in EFL high school teachers' reading instructional practices before and after a reading strategy training program?

Method

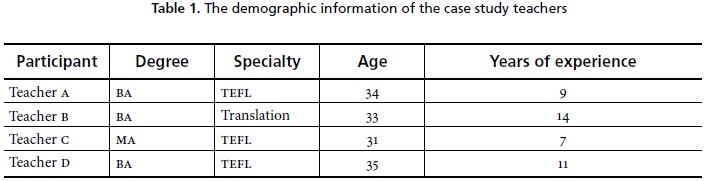

Four EFL female high school teachers, teaching in Babol, a city in the north of Iran, voluntarily took part in the study. Table 1 shows the demographic information of the participants.

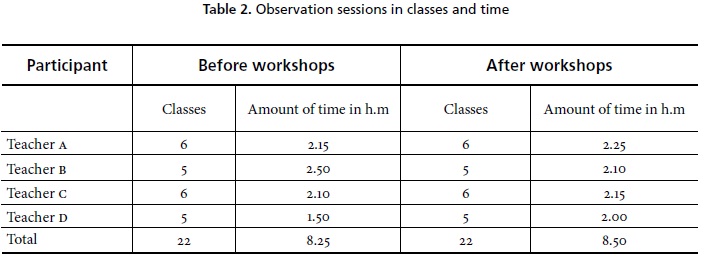

The current study was done in about six months during fall and winter, 2008. The main procedures applied to do the project as a qualitative study were observation, workshops on reading strategy training, and interview. Two series of observations were done and audio recorded by the researchers. One series was done before the workshop and the second after the workshop. The pre-workshop observation of each teacher was conducted from early October to the end of November and the post observation from December to March. The researcher was present in the classes as a non-participant observer observing teaching reading classrooms and taking notes but not contributing her/himself to the practices.

Table 2 shows in detail the observations done for each teacher in classes and time.

Three three-hour workshops were held in three weeks in one of the case study teachers' private tuition classrooms equipped with a whiteboard, a laptop, a table and chairs. Teachers and the researcher sat around the table. A combination of lecturing presentations, handouts, worksheets, and whole group discussions were presented. There were lecture sessions, moving on to the main segment of the workshop, and usually ending with a group discussion. The main segment of the workshop included a number of different awareness-raising activities (Ellis, 1986). The main aims of conducting the strategy training workshops were having the teachers reflect on their teaching methodology regarding reading; examining the observation session regarding the amount and quality of teaching reading strategies; making the teachers familiar with the theoretical basis of learning and reading strategies; making the teachers familiar with what the research says about the effectiveness of teaching reading strategies in reading classes; and modeling explicit teaching of reading strategies and so on. At the end of the final workshop, teachers completed a program evaluation questionnaire to assess the usefulness of the three-week project.

An unstructured type of interview was used in the current study. There was no list of questions. The researcher developed her own questions "to help respondents to open up and express themselves in their own terms and at their own speed. Unstructured interviews are more similar to natural conversations, and the outcomes are not limited by the researcher's preconceived ideas about the area of interest" (Mackey & Gass, 2005). During the breaks and especially when the teachers didn't have a class between two periods, the researcher had the opportunity to speak with the teachers informally, which helped immensely in understanding them and their teaching approaches.

Results

Case Study A

Teacher A had divided teaching reading into three major activities: pre-reading, while reading, and post-reading activities. Teacher A presented a summary of the passage or told the students what was going to be read in the passage in the pre-reading period. In the while reading period, she used strategies like reading aloud, paraphrasing, translating, retelling in L1 or L2, and asking questions to check the students' comprehension. In post-reading activities, the lesson's comprehension exercises were done. These exercises usually encompass some yes/no questions, true/ false statements, and multiple choice questions. It should be noted that the students' proficiency influenced the degree of the use of while reading strategies. For example, the teacher allotted more time to translation in less proficient classes while she spent more time on paraphrasing and retelling in more proficient classes.

It seemed that teacher A's knowledge and awareness of learning and reading strategies were rather low. Through the interview and the workshop questionnaire, she defined language learning strategies as listening, speaking, reading, and writing. In fact, she called language skills language learning strategies and like other teachers, used summary instead of retelling in her teaching.

Through observation, it was obvious after the workshops that teacher A's reading practices, which included pre-reading, while-reading, and post-reading stages, had differed to some extent. Although the pattern was the same, the strategies used in each stage were more varied. For example, in the pre-reading stage, she employed strategies like identifying the title by using the book's pictures, asking the students to predict what would be found in the text, and asking the students to scan the text and find sentences related to the pictures. In while reading activities, when the students asked the meaning of some words, she explained that they could skip the unknown words and pay attention to the whole meaning of the sentences. Sometimes, she elicited some contextual clues and asked the students to guess the meaning of the unknown words.

Regarding post-reading activities, teacher A asked the students' opinion about the text and how they felt. She also asked them what they thought of the passage and how correct they thought their guess was. As teacher A had noted in her reflective journal: "after the workshop, I asked the students to predict the content of the text by identifying the title. I explain to them how to guess unknown words or skip them".

It seemed that teacher A had some reflection on her teaching when after a reading class she told me, "I think giving a summary of the text or explaining what the text is about is not an effective strategy for activating the students' background knowledge. They are not involved in the process and I am the only person who transmits the information. When the students guess or predict the content, they are motivated to find out how right or wrong their guesses are. They are involved in the process of teaching. I think more students took part in the activities today. It's a good method and the students like it. It's more like a puzzle to be done".

Case Study B

Interview and observation revealed that teacher B's main concern was getting the meaning of the words, sentences, and the paragraphs thoroughly. As she herself stated in the interview, "because of my major, translation, I believe we can't understand a text unless we translate it". She used strategies like reading aloud, translating, and asking questions to check students' comprehension. She also did the lesson's comprehension exercises at the end.

Teaching reading was the last session of each lesson. She taught the new words in the previous sessions and asked the students to memorize the list of the vocabulary before reading the passage. She also emphasized that students study the passage at home before they were taught. As she herself noted: "A reading passage is taught when all the students know the exact meanings of the words in the text with their synonyms and antonyms (these are taught in previous sessions)". She was very sensitive to pronunciation and grammatical points. She often interrupted her reading aloud to emphasize pronunciation. She also explained the grammatical points while she was translating the sentences. Teacher B had the same model of teaching reading in all classes. She often told me that it was not really necessary to observe all her classes. She did the same for all classes.

Teacher B's answers to the questions on the workshop questionnaire -How do you define learning strategies? and How do you define reading strategies?- showed that she was not aware of learning and reading strategies. She had noted, "Learning strategies are the strategies we use in teaching a foreign language" for the first question. Defining reading strategies, she had noted, "reading strategies are the ones which help us learn a reading and get the main idea of it. They enable us to answer the questions made by a person about the text".

After the workshops, teacher B like teacher A employed some new strategies in teaching reading. The most distinguished strategy was implementing the pre-reading stage. She didn't use any pre-reading strategy before the workshop. Teacher B dealt straightly with the text before any introduction. But after the workshop she activated the students' background knowledge by asking some questions related to the topic.

For while-reading activities, although teacher B was still sensitive to the exact meaning of the words and phrases, she began to employ some strategies like scanning and silent reading.

There was no change in post-reading activities. Therefore, although teacher B continued with her methodology, she employed some new strategies in her practices.

Case Study C

The workshop questionnaire and interview showed that teacher C like teacher A had divided teaching reading into three activities: pre-reading, while-reading, and post-reading activities. Observation revealed that teacher C used a variety of strategies during the pre-reading stage. She introduced the title by showing the book's pictures. She also asked some questions about the pictures and wanted the students to predict a relation between the pictures and the text. She also asked the students' opinions about the pictures and the title. Using these strategies, she tried to activate their background knowledge.

In the while-reading stage she employed strategies like silent reading, retelling in L1, asking some questions to check the students' comprehension, and translation of the text by the more proficient students.

For post-reading activities, she asked some questions about the passage and then asked the students to do the book's comprehension exercises.

It seemed that teacher C had come to a pattern for teaching reading although there were some minute differences in different classes. For example, in one class she gave the students time for silent reading and then asked some display questions to check comprehension while in another class she wrote some questions on the board and then asked the student to find the answers as they were reading the paragraph silently. Teacher C never explained grammatical points or read the text aloud. She sometimes explained the words by giving synonyms or antonyms. It seemed that she believed that linguistic strategies were not important in reading comprehension and her responses to the questionnaire confirmed it. She had reported that she never taught grammar or asked the students to read aloud while teaching reading.

According to the workshop questionnaire, interview, and the methodology teacher C used in teaching reading, it could be inferred that she was aware of language learning and reading strategies. It seemed that her degree, M.A. in TEFL, to some extent had distinguished her from her colleagues.

After the workshops, teacher C like teachers B and A began to teach and use more strategies in her practices. For example, before teaching a passage entitled "Learn a Foreign Language", consisting of two paragraphs each being a very short story, she explained that the text type was narrative. She talked about the paragraph connections. She explained "story grammar" in teaching another lesson and asked the students to retell the story based on the "story grammar". She asked them to identify the setting first, then to explain the events, and finally to reach the conclusion or solution. She also explained by having this order in mind, they could easily find the paragraphs' connection. In all her classes that I observed after the workshop, she taught the students how to write a summary of a passage. She had noted the following in her reflective journal: "I have found out that I must teach the students how to summarize a text. I am from those teachers who always asked the students to tell a summary but I never had taught them how to do that. In fact, what my students were doing was retelling not summarization". It seemed that teacher C also had reflected on her reading practices.

Case Study D

Teacher D, like teacher A and C, presented her reading instructional practices in three stages: pre-reading, while-reading, and post-reading. For the pre-reading stage, she wrote the title of the reading on the board and clarified its meaning. For example, in teaching a passage entitled "The boy who made steam work", she asked the meaning of the word "made". The students answered and then she explained thoroughly the different meanings of "make".

In while-reading activities she first read aloud the passages paragraph by paragraph. Then she asked the students to read the paragraphs silently. Finally, she asked some questions to check the students' comprehension. She did the same for all paragraphs. She paraphrased some sentences that she felt the students had not entirely understood. Sometimes, she explained some grammatical points.

For post-reading activities, she asked the students to do the comprehension exercises. Of course, she checked only true/false and multiple choice exercises.

In the interview, teacher D stated, "I ask the students to study the passages at home before I teach them. I explain the meaning of the vocabulary list at the first session of each lesson. So, the students are provided with the meaning of the words and they can comprehend the passages. When I teach the passage, they should pay attention and understand the parts that they could not cope with by themselves". Based on the interview, the workshop questionnaire, and my observation, it seemed that teacher D employed the same methodology in all her classes.

The observation done after the workshop revealed that teacher D didn't change her practices considerably. She only specified more time for silent reading.

To be brief, observation revealed that teachers employed some reading strategies in their practices but no explicit teaching of reading strategies was observed before the workshops. They employed some strategies like paraphrasing, silent reading, retelling, translating, and asking questions to check comprehension in their practices. The observation showed that paraphrasing was the most frequently used strategy and the teacher's giving a summary was the least frequently used. All four teachers used paraphrasing in their practices while only one teacher gave a summary of the text. Three out of four teachers employed more reading strategies in their practices and began to teach reading strategies explicitly after the workshops. It seemed that the dominant teaching reading methodology by the four teachers was the pattern of pre-reading, while-reading, and post-reading activities. It was employed by three out of four teachers before the workshops. It remained the dominant pattern after the workshops and all the four teachers employed it.

Discussion and Conclusions

Three main results were obtained from the study. First, the observation revealed that teachers did not explicitly teach any reading strategy in their reading classes. However, they employed some strategies like paraphrasing, silent reading, retelling, translating, and asking questions to check comprehension in their practices. The observation showed that paraphrasing was the most frequently used strategy and summarizing by the teacher was the least frequently used strategy. This result was obtained from eight hours and twenty minutes' observation of high school reading classes.

Reviewing the literature, the researchers could not find a compatible study in the EFL/ESL context. However, the literature confirms the mentioned findings in the L1 context. Major findings of Durkin's study (1979) through classroom observations of reading and social studies in elementary schools included the fact that almost no comprehension instruction was found. The attention that did go to comprehension focused on assessment, which was carried on through teacher questions. Instruction other than that for comprehension was also rare. Teachers actually devoted two percent of classroom time designated for reading instruction to teaching students how to comprehend what they read. Ness (2007) also collected data from forty hours of direct classroom observations in eight middle and high school science and social studies classrooms. The study showed that just over 3 percent of instructional time was devoted to reading strategies.

The above findings might mean that high school teachers emphasize breadth over depth (Ness, 2007). EFL teachers are likely to see their major instructional responsibility as covering the books and preparing their students to pass the final exams.

Second, the dominant methodology of teaching reading by the four teachers under study was the pre-reading, while-reading, and post-reading model.

Third, observation done after the workshops revealed that the strategy training workshops affected teachers' practices in several ways as follows:

- One out of four teachers did not make a considerable change to her practices.

- Three out of four teachers began to teach reading strategies in reading classes.

- They modified their reading teaching methodology.

- The strategies they used in teaching reading became more varied.

- They replaced some strategies with new strategies.

- They began to reflect on their teaching methodology.

Studying the interplay between teachers' beliefs, instructional practices, and professional development regarding grammar, Mohamed (2006) also found that by the end of a development program two of the teachers had started using grammar discovery tasks in their teaching. Several of the other teachers had also started to make some changes to their teaching. Four teachers continued to teach without making any alterations to their practices. Looking into the literature on teacher change, the sentiment one can find expresses that teachers do not change and teachers are not manageable (e.g. Duffy & Roehler, 1985; Fullan, 1991, as cited in Richardson, 1998). Regarding the time of teacher training strategy (9 hours), it seems that teachers revealed considerable change in their practices. Of course, it is not clear whether they continued the implementation or not. I think the main reason for teachers' change in this study is that teachers voluntarily took part in the study. They willingly took part in the workshops and, as the program evaluation questionnaire revealed, they aimed to implement reading strategies in their classes as much as their classes could accommodate them. Other reasons are the ages and the teaching experiences of the case study participants that ranged respectively from 31-35 and 7-14 in this study. According to Hargreaves (2005), teachers in the early stages of their career were the most open to change, and those nearing the end of their career showed the most resistance while mid career teachers who were relaxed in their professional duties were also fairly flexible and positive toward change.

Several practical implications of the study, especially concerning EFL teachers, teacher trainers, material developers, and educational managers, can be identified. It is recommended that EFL high school teachers be aware of the effect of reading strategies in improving reading skills. They should try to enhance their professional knowledge to be compatible with the current research findings and theories. Furthermore, teacher trainers are expected to familiarize their students with these effective factors in successful teaching. Furthermore, material developers are required to design materials which encompass explicit teaching of reading strategies while preparing the materials for schools. If explicit teaching of reading strategies becomes a part of the textbooks, EFL teachers will surely pay more attention to it. Finally, pre-service education alone is not adequate to fully prepare a teacher for a lifetime of teaching. In-service teachers need to be made aware of different models and approaches of teaching and be provided with opportunities to put these into practice. Teachers must be regarded as learners who need to continually expand their knowledge and improve their practices. All the above issues can be obtained via systematic and continuous in-service training programs. As a final note on the limitations of the research, the subjects of the study were limited to five female EFL high school teachers in Babol. The researcher doubts whether the findings will be applicable to other places as well. And, the presence of the researcher, as any other observation, may have affected the teachers' behavior.

References

Alderson, J., & Urquhart, A. H. (1984). Reading in a foreign language. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Bamford, J., & Day, R. R. (1998). Teaching reading. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 18, 124-141. [ Links ]

Cambourne, B. (1999). Explicit and systematic teaching of reading: a new slogan? The Reading Teacher, 53(2), 126-127. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

Dole, J. A. (2000). Explicit and implicit instruction in comprehension. In B. M. Taylore, M. F. Graves, & P. van den Broek (Eds.), Reading for meaning: Fostering comprehension in the middle grades (pp. 52-69). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. [ Links ]

Durkin, D. (1979). What classroom observations reveal about reading comprehension instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 14, 481-533. [ Links ]

Ellis, R. (1986). Activities and procedures for teacher training. ELT Journal, 40(2), 91-99. [ Links ]

Hargreaves, A. (2005). Educational change takes ages: Life, career and generational factors in teachers' emotional responses to educational change. Teaching & Teacher Education, 21, 967-983. [ Links ]

Khonamri, F. (2008). An investigation of the relationship between ESL readers' beliefs, metacognition and their strategic reading behavior. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, PUC, India. [ Links ]

Krashen, S. D. (1995). Immersion: Why not try free voluntary reading? Mosai, 3, 1-4. [ Links ]

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. (2005). Second language research: Methodology and design. New Jersey: LEA. [ Links ]

Mohamed, N. (2006). An Exploratory study of the interplay between the teachers' beliefs, instructional practices, and professional development. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The University of Auckland, Auckland. [ Links ]

Ness, M. (2007). Reading comprehension strategies in secondary content-area classrooms [webpage]. Retrieved from http://www.pdkmembers.org/members_online/publications/Archive/pdf/k0711nes.pdf. [ Links ]

Pressely, M. (2000). Comprehension instruction in elementary school: A quarter-century of research progress. In B. M. Taylore, M. F. Graves, & P. van den Broek (Eds.), Reading for meaning: Fostering comprehension in the middle grades (pp. 32-51). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. [ Links ]

Richards, J. C., & Farrell, T. S. C. (2005). Professional development for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Richardson, V. (1998). How teachers change [webpage]. Retrieved August 24, 2010, from: http://www.ncsall.net/?id=395. [ Links ]

Roshd. (1980). English group news. EFL Journal of Lesson Planning and Curriculum Design, 6, 28-29. [ Links ]

Shen, H. J. (2003). The role of explicit instruction in ESL/ EFL reading. Foreign Language Annals, 36(3), 424-433. [ Links ]

Willingham, T. D. (2006). The usefulness of brief instruction in reading comprehension. American Educator, Winter, 39-45, 50. [ Links ]

About the Authors

Fatemeh Khonamri is an assistant professor of TEFL in the English Department, at Mazandaran University in Babulsar, Iran, and an M.A. candidate of TEFL at the same university. Her main fields of interest include EFL teacher education and learning strategies. She is also interested in research on reading and writing, assessment, cooperative learning, and autonomous learning.

Mahin Salimi holds an MA in TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) from the English Department of the University of Mazandaran in Babulsar, Iran. Her main fields of interest include EFL teacher education and learning strategies.