Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.13 no.1 Bogotá Jan./Apr. 2011

Grassroots Action Research and the Greater Good

La investigación acción de base y el bien mayor

Isobel Rainey

GESE/ISE Panel for Trinity College London, United Kingdom

isobelrainey@googlemail.com

This article was received on May 3, 2010, and accepted on November 27, 2010.

This study examines the action research topics and topic preferences of two groups of grassroots teachers: active researchers, and potential researchers. The analysis of the topics appears to indicate that, over the past decade, action research at the teaching of English at the grassroots level to speakers of other languages has been principally understood in terms of professional development with respect to teachers' methodologies and learners' learning behaviours. A nascent concern for a more ample approach to professional development and issues conducive to the greater good of the profession can, it is mooted, flourish only with the collaboration of all relevant stakeholders.

Key words: Collaboration, comprehensive professional development, grassroots action research, research topics.

En este estudio se examinan los temas de investigación acción y los temas preferidos por dos grupos de profesores de base: uno de investigadores activos y otro de investigadores potenciales. El análisis sugiere que, durante la última década, la investigación acción en el aula de inglés para hablantes de otras lenguas se ha entendido principalmente en términos del desarrollo profesional con respecto a las metodologías de los profesores y las conductas estudiantiles de aprendizaje. Se considera que un incipiente interés por un enfoque más amplio y por asuntos conducentes al beneficio general de la profesión, solamente puede florecer con la colaboración de todos los actores más importantes.

Palabras clave: colaboración, desarrollo profesional integral, investigación acción de base, temas de investigación.

Introduction

The motivation for this study derives from the author's experience as an avid reader of the reports of the action research projects of EFL teachers working at the grassroots level and from her hunch, as a result of her reading, that the sources from which the teachers select their research topics are rather limited -for example, to aspects of their teaching methodologies and their learners' learning behaviours. As a result, the impression given is that the teachers' putative professional self-development cannot be described as fully rounded and, furthermore, the potential for the knowledge generated by the research projects to impact the TESOL profession as a whole, either at national or international levels or both, is somewhat restricted. In identifying these potentially problematic issues, this paper is not suggesting that achievements in this area of TESOL research have been either inadequate or insubstantial. On the contrary, over the past ten years, and particularly since the launch of journals like PROFILE, progress has been quite remarkable, reaching far beyond the dismal predictions of many action research doubters. Inasmuch as it is always good to take stock of what is being achieved in any research field lest important issues are overlooked, this paper aims to do precisely that.

The paper begins by revisiting briefly aspects of the works of Dewey (1923), Lewin (1948) and Stenhouse (1975), who, either directly or indirectly, have had a major influence on the theory of educational action research. It goes on to define what is meant, in the context of this study, by the term 'grassroots (EFL) teachers' and to identify and analyse the main sources of the topics selected by a group of published teacher-researchers working at the TESOL grassroots level and by a group of potential action researchers for their action research projects.

Sources of data for the study include documentary evidence in the form of the topics of articles published in an academic journal, the principal aim of which is to publish grassroots EFL teachers' action research reports, and the topics of chapters in a book also reporting EFL teachers' action research as well as two questionnaires (one closed; one open) completed by group of potential grassroots action researchers who were participants at a symposium on action research. The data derived from the documentary evidence are analysed in terms of a framework of factors influencing teaching and learning, as reported in the literature review, and of the difficulties EFL teachers face, established in the discussion on grassroots teachers; the analysis of the questionnaire involves basic descriptive statistics, accompanied by critical reflection. As anticipated, the data reveal that the choices of topics for the action research projects of both groups do not represent a comprehensive treatment of all their needs in respect to their immediate teaching contexts; nor is there a marked tendency to address issues pertaining to the wider scope of TESOL. The conclusion to the study is, however, not pessimistic. Rather, it acknowledges the achievements of the grassroots teachers in terms of their action research activities and celebrates the contribution these activities have made to building up the teachers' sense of self-worth (Cárdenas, 2003; Stringer, 1999, p. 24) and to creating formal written records of grassroots EFL teacher expertise and knowledge. At the same time, it reminds traditional researchers in the field of Applied Linguistics: TESOL that, if, in line with Dewey, Lewin and Stenhouse, the greater good is to be served through action research at the grassroots level, they need to draw on and respect this knowledge in their teacher training and development programmes; by the same token, they need to work collaboratively with their grassroots colleagues in order to facilitate research into areas they appear to find excessively challenging if working alone.

Bases of and Developments in Action Research

When a theory becomes popular in a given profession, it is not uncommon for academics, in their enthusiasm, to publish enormous amounts of literature reporting their interpretations of, views on, and even modifications of that theory. Educational action research is no exception to this rule; nor is action research in TESOL. The volume of literature produced over the past three decades through conventional publications and on the internet is overwhelming; more importantly, in its detail it has sometimes obscured, even overlooked, the original, clear and important bases on which action research has been constructed. It is, therefore, in the interests of clarity and strength of argument that this overview of the contributions of Dewey, Lewin, and Stenhouse to the genesis of, and developments in, action research theory1 is brief and focused on those aspects of their philosophies and beliefs which pertain directly to action research or, in Dewey's case, to active learning.

Views of Knowledge and the Active Learner: Dewey

It is generally believed that the term action research was coined by Lewin, who used it for the first time in his writings in 1946 as follows:

The research needed for social practice can best be characterized as research for social management or social engineering. It is a type of action-research, a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action, and research leading to social action. Research that produces nothing but books will not suffice. (Lewin, 1946, reproduced in Lewin, 1948, pp. 202-203, cited in Smith, 2001)

Although Lewin may have been the first person to use the term and to propose the procedures for the conduct of action research (see below), the pragmatic principles underpinning some of Dewey's writings would appear to have prepared the way for educational action research. Dewey posited, for example, that the "development of knowledge was fundamentally an adaptive response to the environment" (Dimitriadis & Kamberelis 2006, p. 5) and defined the environment itself as "whatever conditions interact with personal needs, desire, purposes, and capacities to create the experience which is had" (Dewey, 1938, p. 44, cited in Dimitriadis & Kamberelis, 2006, p. 5). Rejecting the view that knowledge could be represented in the form of an encyclopaedic copy of all the facts about the universe, Dewey, thus, proposed that

(i)t is the expression of man's past most successful achievements in effecting adjustments and adaptations, put in a form so as best to help sustain and promote the future still greater control of the environment. (Dewey, 1977, p. 179)

This view on the development of knowledge sits well with action research as teachers are encouraged to practise it today. Action research is done 'by the teachers and for the teachers' (Mertler, 2009, p. 4) and

(i)s defined as any systematic inquiry conducted by teachers, administrators, counsellors, or others, with a vested interest in the teaching and learning process or the environment for the purpose of gathering information about how their particular schools operate, how they teach and how their students learn. (Mills, 2007, p. 10, cited in Mertler, 2009, p. 5)

With respect to understanding and controlling the environment, Caillods and Postlethwaite's detailed, though not exhaustive, breakdown of factors affecting teaching and learning is a useful reference for checking that research aimed at improving that particular environment is in fact looking at it from all, or most, of the relevant angles.

Many factors operate to produce pupil learning and achievement. The child's home background, the curriculum, the materials, the language used, the time devoted to instruction and homework, the work ethos of the school, the pupil's motivation, the teachers' perception of the ability of the class, their education and status, their behaviour, and teaching practices all intervene in this network of influences (Caillods & Postlethwaite, 1989, p. 182).

Thus, knowledge is for action researchers what it was for Dewey, not "an a priori psychological or ontological phenomenon" but "an effect of goal-directed activity" (Dimitriadis & Kamberelis, 2006, p. 5) on factors in the environment which are of special interest to them -either because they represent a challenge or because they represent success (see Discussion and analysis of data for a consideration of teacher researchers' need for success). Furthermore, Dewey believed that if collectives of individuals worked together, they could make life better through experimentation and inventiveness, finding their own answers to questions rather than accepting dogmatic answers handed out to them by authority (Barrow & Woods, 1988, p. 135). This belief finds resonance in modern theorists who see action research as fundamentally, maybe even exclusively, collaborative2.

Action research is collaborative (italics in the original): it involvesthose responsible for action in improving it ...it starts with small groups of collaborators at the start, but widens the community of participating action researchers so that it gradually includes more and more of those involved and affected by the practices in question (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1992, pp. 22-5).

At this point, it is worth noting that much of what Dewey wrote on education focused on the learners and on his concerns that they should be 'active learners' within the context of their educational experiences and, as a result,"become tolerant and rational adults, able to cope with a relatively high degree of social freedom without abusing that freedom to interfere with the freedom or well-being of others" (Barrow & Woods, 1988, p. 134); that is, in the long-term, education was for the greater good, the good of the community as a whole.What Dewey had to say about the (child) learners was subsequently applied to adult learners, and specifically in the case of TESOL to EFL teachers in pre-service, in-service and teacher development programmes. This is most likely due to the influence of Lewin.

Experiential Learning and Democracy in Teacher Training: Lewin

It was Lewin who, quite fortuitously3, first realised that the underlying principles of Dewey's work could also be applied to teachers in initial and/or in-service training. His approach, not surprisingly, perhaps, given that the 'learners' with whom he was dealing were adults, emphasised the contribution to learning that the trainees could make if the programmes were organised along democratic lines. Kolbsummarises Lewin's beliefs thus:

(l)earning is best facilitated in an environment where there is dialectic tension and conflict between immediate, concrete experiences and analytic detachment. By bringing together the immediate experiences of the trainees and the conceptual models of the staff in an open atmosphere where inputs from each perspective could challenge and stimulate the other, a learning environment occurred with remarkable vitality and creativity. (Kolb, 1984, p. 10)

Lewin's convictions about how training is better effected through creative and dynamic learning environments, where theorists and practitioners participate in a democratic debate, are echoed today in Winter's principles of action research4. Action research creates "... plural structures, which involves developing various accounts and critiques, rather than a single authoritative interpretation" (Winter, 1996, pp. 13-14). Lewin also had a strong belief in the need for a close integration of theory and practice "There is nothing so practical as a good theory" (1952, p. 169), and this is reflected today in the claim that action research "makes for practical problem solving as well as expanding scientific knowledge" (Cohen et al., 2000, p. 228). Lewin's greatest contribution to the action research debate is probably his proposal for the process by which action research should be conducted, as illustrated in his by now ubiquitous Action Research Spiral (Mertler, 2009, p. 15); nevertheless, a discussion of how to conduct action research falls outside the scope of this study. It is, here, sufficient to emphasise that, like Dewey, he believed in a collaborative, democratic approach to the educational process in active experiential learning, all of which would lead to both the resolution of immediate problems and the generation of knowledge which would have the potential to add to and widen the scope of professional understanding.

Teachers as Researchers and Curriculum Reform: Stenhouse

Although it was Lewin who coined the phrase action research, it was Stenhouse (1975) who was responsible for promoting the notion of the teacher as researcher. He cast the teacher in the role of learner with respect to "both their subject matter and their pedagogical knowledge" (Elliott & Chingtien, 2008, p. 569), insisting that any major attempts at curriculum reform could be effective only if they were informed by teacher research (Kemmis, 1995, p. 74). Like Lewin, Stenhouse believed in a good theory but for him the theories for teaching should derive principally from teachers' practices. Thus, action research involved teachers in theorising about their practices and these theories were to contribute to curriculum reform. Aware of the exigencies of such projects, he also acknowledged that there was "a need to evolve styles of cooperative research by teachers using full-time researchers to support the teachers" (1975, p. 62), and that "the emergence of a healthy tradition of curriculum research and development depends upon a partnership of teachers and curriculum research workers" (Stenhouse, 1975, p. 207). He was most insistent, however, that it was ultimately the teachers' influences which would prevail. Research workers have a contribution to make, but it is the teachers who in the end will change the world of the school by understanding it (Stenhouse, 1975, p. 208).

In an age of globalisation and of the hegemony not only of English as the language of international communication but also of the curricula and methodologies for teaching it (Phillipson, 1992), such an approach offers a welcome opportunity for EFL teachers and curriculum reformers working in non-Western contexts to design more appropriate, even less threatening, curricula for their specific contexts. Thus, Elliott and Ching Tim, writing in their case about East Asia, maintain that curriculum reform

(n)need not draw exclusively on ideas from the West. Within the educational traditions of East Asian societies lie cultural resources for the creative reconstruction of teaching and learning as an educational process. The value of the encounter with Western educational ideas for East Asian educators is that it can heighten their awareness of ideas embedded in their own cultural traditions and their similarities and differences to Western ideas. Indeed such encounters provide opportunities for mutual learning between Eastern and Western educationists. (2008, pp. 573-574)

It is worth noting that Elliott and Ching Tim Tsai do not exclude Western ideas when curricula are being designed in non-Western contexts; rather, they favour an approach where both communities are learning from one another.Also worth noting is that what Elliott and Ching Tim have to say about East Asia can easily apply to many other regions of the world, Eastern Europe, South America, the Middle East to mention just a few.

Summary

This brief overview of the genesis of, and developments in, action research reveals, in terms of the three influential theorists discussed, the importance they ascribed to active learning for the growth and edification of the whole person and for the community in which he/she studied, lived or worked; a democratic and collaborative approach to generating the knowledge relevant to such growth; and, specifically in terms of educational curriculum reform, a firm belief that reforms could work only if they were based principally in the outcomes of teachers' action research. The extent to which action research is being practised in these terms in the TESOL grassroots realm is one of the main concerns of this study, but first it is necessary to clarify what is meant here by the term 'grassroots'.

Grassroots EFL Teachers

Grassroots EFL teachers are traditionally regarded as those who teach in difficult circumstances at primary and secondary schools in developing countries, for example, Algeria, Brazil, Cambodia, Mexico, Peru, Thailand, and Vietnam, where English is widely studied for specific purposes, such as reading scientific and technical literature and facilitating communication in business and tourism. Furthermore, these countries do not have a tradition of English being used as a second language in, for example, governance, education, the press. They correspond roughly to the category of expanding countries, as proposed by Kachru (1985), contrasting roughly with outer circle countries where English has varying degrees of institutionalised functionality. Kachru's concept of the inner circle i.e. countries like Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the USA, where English is the first language, is quite useful in the context of this study but the other two categories are not considered all that useful: many outer circle countries (Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Sudan, for example) are developing countries and teachers in these contexts, despite erstwhile colonial connections with inner circle countries, still face many difficulties in their teaching experiences; and these are just as severe, if not more so, than those of teachers in expanding circle contexts. Furthermore, in terms of this study, it is considered inappropriate to limit the term 'grassroots' to one specific type of country.

That in many developing contexts investment in education is inadequate and opportunities for teachers and learners to interact with speakers of English as a first language are severely limited is here not disputed. Some of the difficulties which teachers in these contexts face are vexing and have been identified, for example, as follows: in Uzbekistan, scanty resources and low salaries (Hassanova & Shadieva, 2008); in Argentina, problems with discipline bordering on the violent (Zappa-Hollman, 2007); in Malaysia, limited English language competence (Kamarul Kabilan, 2007); and the demands of unrealistic recently imposed CLT curricula on teachers who lack the linguistic competence and/or pedagogical skills to implement them - all three contexts: (Hassanova & Shadieva, 2008; Kamarul-KIabalin, 2007; Zappal-Hollman, 2007). These difficulties find resonance in the field of general education as stated below:

[t]eachers work with 45-50 students in crowded spaces with few resources and are paid salaries below what is required to sustain a family. They often have other jobs in order to garner reasonable resources. (Saud & Johston, 2006, p. 17)

It would be somewhat naive to assume, nonetheless, that the difficulties faced by these teachers (note that outer circle countries [Malaysia] as well as expanding countries are represented) are exclusive to developing countries. In terms of this paper, what makes teachers 'grassroots teachers' is not the specific difficulties they face, or the geographical or historical relationship of their country to the inner circle; what makes them grassroots is that, irrespective of where they teach, they face daunting difficulties of one type or another in their day-to-day classroom realties. Thus, Appel (1995), who narrates -poignantly- how he grappled for a whole year with one major source of difficulty, namely discipline, in his secondary school in Germany, which is supposedly 'an outer circle context', is in terms of this article a grassroots teacher. Despite coming from different circle (viz Kachru) backgrounds, Prodromou and Clandfield (2007) have identified similar sources of difficulties in their teaching contexts and have recently collated their strategies and suggestions for dealing with them. Even in inner circle or mainstream contexts, where the material, organisational and professional circumstances in which teachers work tend to be satisfactory (well-equipped classroom; small group teaching; mother or near-mother tongue teachers with a good command of the language and an up-to-date working knowledge of FL teaching methodologies), teachers can encounter intractable problems which have a dampening effect on teacher performance and learner achievement. Senior (2006) found, for instance, that ESL teachers working in Australia often had to deal with challenging affective inhibitors, which resulted in worried students, reluctant students and culture-shocked students, among others (p. 27).

In terms of this study, therefore, a salient characteristic of grassroots teachers is that they are teachers for whom a lot, if not all, of the joy has been taken out of their teaching or out of their learners' learning experiences, or both because of one or more prevailing difficulties (viz Appel, 1995). Another characteristic is the extent to which the teachers have the power to do something about their difficulties. Within the constraints of traditional, top-down educational settings, grassroots teachers are seldom in a position to do much about their problems; quite the opposite in fact, because in these circumstances:

(t)he teacher's task is reduced to that of bringing about certain pre-specified behavioural changes in all pupils in a predetermined stereotypical manner. Neither teachers nor pupils are considered as individuals with the need to teach and learn in mutually responsive ways toward ends that they themselves have agreed upon. (Clark, 1987, p. 34, cited in Appel, 1995, p. XIV)

In the 1980s and 1990s, action research was heralded in the field of education as a process by which teachers could be empowered not only to do something about the difficulties they encountered in their immediate teaching contexts but also something for the wider educational setting within which they operated. In this interpretation, action research is regarded as "a dual mechanism for transforming the curriculum and for the empowerment of teachers" (Somekh, 2006, p. 59). The practice of action research by TESOL grassroots teachers, in theory, anticipated a long-awaited situation where action research would contribute to teachers' professional self-development and where the outcomes of teachers' research would, through a bottom-up process, be fed into curriculum reform, thus effecting a change in attitude within central ministries of education for whom "most knowledge which is valid is that produced by the ministry" (Riddell, 1999, p. 384). Thus, in addition to examining the extent to which action research is being practised in line with principles of Dewey, Lewin and Stenhouse, this study examines the extent to which it is fulfilling its promise for the TESOL grassroots realm.

The Study

The discussions in the two foregoing sections suggest the following research questions as a focus for this study:

a) To what extent, if any, are the teachers in this study being empowered through their action research activities?

b) Is the research, as practised by the active researchers, or as would be practised by the potential researchers, comprehensive? In other words, does it (would it) address a wide spectrum of the factors influencing and challenging teaching and learning in their situations?

c) Is the action research carried out not only for the teachers' professional self-development but also for the greater good i.e. for the community of TESOL educators and learners as a whole?

d) Is there evidence that teachers or professional researchers and teachers work collaboratively on their action research projects?

Sources of Data

Data for this study are the action research topics and research topic preferences of two groups of EFL teachers. Group 1 is made up of teacher researchers who have already done, and published reports on, their own action research projects. Group 2 comprises a large group of potential action researchers. It is mooted that analyses of the topics of the published articles and of the topic preferences of the potential researchers lead to an appreciation of the extent to which action research, as practised by group 1, and as it would be practised by group 2, is contributing or has the potential to contribute to the ample professional development of the teachers and to progress in the profession as a whole.

Group 1 teachers have published their research reports in (a) PROFILE, an academic journal produced at the National University of Colombia, Bogotá campus; the express purpose of the journal is to facilitate the space for grassroots EFL teachers to report their action research projects; it was selected as the main source of data for this group as it is the only academic journal this author knows of which consistently reports the action research findings of grassroots EFL teachers working in primary and high schools (henceforth PS and HS, respectively); and (b) in Action Research in English Language Teaching in the UAE (henceforth, ARUAE), a book published by the Higher Colleges of Technology in the United Arab Emirates, which reports the action research experiences of a small group of pre-service teachers in the context of the teaching practicum component of their undergraduate degree courses. There are more data for the Colombian (PROFILE) than for the UAE publication. It is not the intention here to establish a comparison of the value or success of these two publications. Although the contribution from the UAE publication is small, it provides not only a second concentrated source of topics selected by EFL school teacher researchers but also a unique example of collaboration between professional researchers and grassroots teachers.

Group 2, the potential action researchers, attended a symposium on action research at the National University of Colombia, Bogotá campus, in December 2009. They were asked to complete two questionnaires: (1) about the difficulties they encountered in their current teaching positions (Appendix 1); and (2) about which topic they would choose, should they be given a chance to do action research (Appendix 2). The data generated by these two questionnaires are voluminous and will not be analysed in all their detail here5; rather, these data are also used to triangulate the data generated by Group 1 and to gauge the extent to which grassroots teachers consider, or do not consider, action research as a path beyond immediate professional development to greater empowerment within the profession. Just as PROFILE was selected for its consistent service to grassroots teacher researchers, the symposium at the National University in Bogotá, Colombia, was used to collect the data for Group 2 because of the enthusiasm with which action research has been embraced by the Colombian TESOL community in general and at the National University in particular.

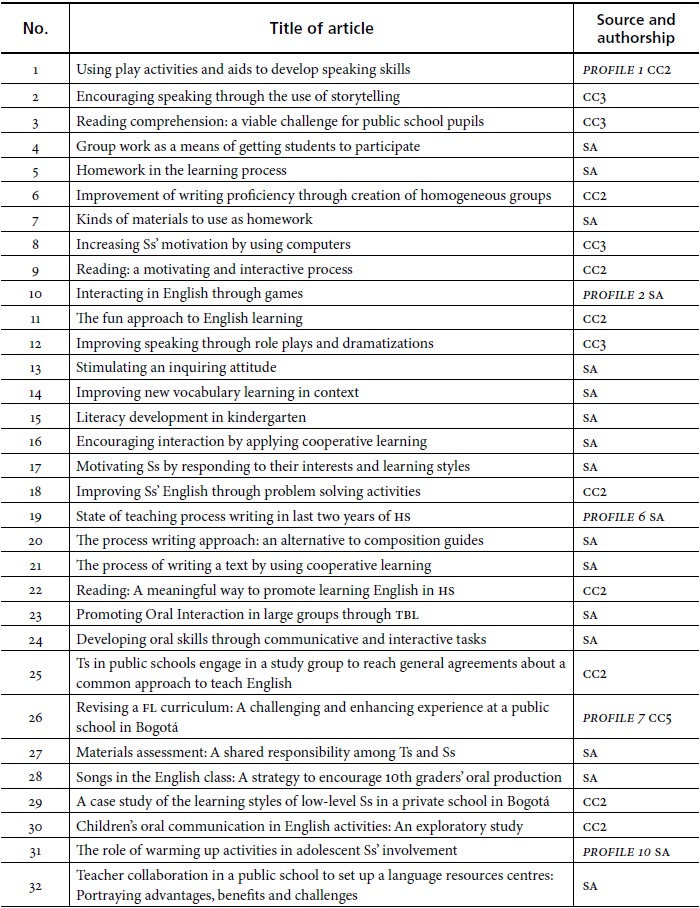

Topics Data: Group 1

The first issue of PROFILE was published in 2000 and the most recent in October 2010. Data for this study are collected from issues numbers 1, 2, 6, 7, 10 and 11(2) which correspond to the years 2000, 2001, 2005, 2006, 2008, and 2009. (PROFILE now has two issues a year; hence 11(2)). Selecting these issues from the beginning, middle and end of the decade offers, it is believed, a fair representation of the trends in PROFILE. In the case of both publications (PROFILE and ARUAE), only those articles pertaining to teacher research at primary and secondary schools are used for the data on the grounds that, in TESOL, it is in these two sectors of education that the grassroots conditions described above are most common and most acute. Thus, articles on the teaching of EFL to adults at universities or language academies were not included in the tally; neither were theoretical-reflective articles as they are not relevant to the present discussion.

Description and Presentation of Data: Group 1

Altogether, the data for this group are made up of 41 topics: 35 derived from the titles of the relevant articles in the six PROFILE journals; six from the relevant chapters in ARUAE. As a title does not always accurately predict the contents of an article, all the articles and chapters were read to ensure that the topic identified through the title is in fact the topic discussed. Similarly, the title may give the impression that the focus of the research is narrow i.e. of interest only to a specific teacher and/ or of little relevance to the profession as a whole, but reading the article may reveal that the focus is not so narrow and the topic may indeed be of wider interest than anticipated. Conversely, titles which promise a wider focus, especially topics containing words like 'approach' are sometimes researched from a very narrow basis. Where these issues arise, they are dealt with in Comments after Table 1.

Table 1 contains the titles of the articles (PROFILE) and chapters (ARUAE) selected. Each entry in Table 1 is given a number for ease of reference within this study. There is a key (below the table) for the abbreviations in the titles and to indicate how the articles were authored; for space-saving reasons, the authorship is recorded in the same column as the source.

Table 1. Sources of topics: data for Group 1

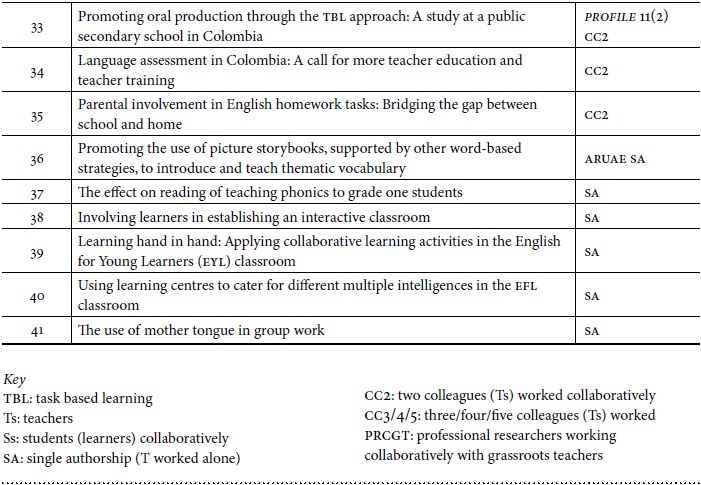

Classification of Data: Group 1, as Presented in Table 2

Table 2 contains the classification of the data for Group 1 into a framework derived mainly from the discussions in 'Genesis of and developments in action research' and 'Grassroots EFL teachers' above. The framework has two main categories: (a) Environmental Issues, which is based on Caillods and Postlewaithe, with some modifications to accommodate the teaching of English as a foreign language (for example, Teachers' FL competence) and recent advances in FL pedagogy (Learner Behaviours, as in strategies and learning styles); and (b) Difficulties, as discussed in Grassroots EFL teachers, and likewise modified in line with EFL considerations (see, for example, Appel, 1995; Prodromou & Clandfield, 2007). The sub categories within each major classification are arbitrary and could, depending on individual teaching contexts, be switched, especially from Environmental Issues to Difficulties. For example, Testing programmes (Environmental Issues) could in some circumstances be classified under Difficulties, as could Students' Home Backgrounds but, unlike the subcategories under Difficulties, they are not inherently problematic. Testing programmes and students' home backgrounds can in fact be supportive of students' learning.

Where topics have a narrow methodological focus, as in 'Songs in the English class: A strategy to encourage 10th graders' oral production' (article 28), they are classified under Teacher methodology. If, however, the methodology issue is of wider application, it is classified under Curriculum (curriculum being used here in its wider sense of the overall FL programme including language content, materials to be used and methodologies to be applied) or under Large classes (see below) for the discussion of topics 16 and 18). Some topics could belong in two subcategories; thus 7 could be classified under Materials or Homework. Where this is the case, the topic is placed in both subcategories without brackets under the subcategory, which is the main focus in the article, and in brackets under the other subcategory. When calculating percentages, however, only the main focus is considered.

Some specific clarifications of the classifications are in order. Articles 4 and 11 would appear to be quite broad in their treatment of the topic but they are in fact narrowly focused: article 4 is concerned with participation in speaking activities, as opposed to participation in the language learning experience in general; article 11 promises a fun approach to learning English in general but deals only with the use of games in the teaching of EFL. Thus, both of these topics are classified in Teacher methodology (see Table 2), not under one of the bigger issues e.g. Curriculum. Article 13 does not do itself justice inasmuch as the wording of the title is so vague but it is in fact about the integration of the science and English curricula in the early years of school and, for this reason, classified under Curriculum (see Table 2). Although article 16 focuses only on improving the skills of listening and speaking, it does so in the context of large group teaching; thus, it is classified in the Difficulties section under Large groups. Article 17 is widely focused taking into account the learner as a whole person when attempting to motivate him/ her and thus classified under the general heading of Motivation. Likewise, article 18 is concerned with the integration of all four skills through a problem solving approach and could, potentially, make a useful contribution to curriculum reform; hence, it is classified under Curriculum.

Five of ARUAE chapters are of interest: 37, 38, 39, 40 and 41. At first glance, all the topics represented in the titles for this publication would appear to offer 'more of the same' in terms of EFL methodologies i.e. the same problems and solutions as those traditionally offered by TESOL pundits from the inner circle. On closer reading, however, five of these action research projects reveal (a) an angle to the topics which is wide enough to make them significant in terms of general teaching methodology throughout the national primary school (all the research reports are PS based) level, and (b) a sensitivity to national realities; thus, these reports could be taken into account for EFL primary school curriculum reform in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and hence their classification under Curriculum issues.

Authorship of the articles reveals that as many as 17, almost 50%, of the 35 PROFILE projects, were carried out collaboratively with two or more colleagues working together. This is an important finding and is discussed under Data analysis below. All of the six ARUAE projects were conducted by a teacher working alone (SA), not surprisingly given that the teachers in question were carrying out their research within the context of their teaching practicum. Of great interest and significance for the current discussion, however, is how such a project (action research in the context of teaching practicum) got started in the first place. It is clear that it is the outcome of international collaboration i.e. of professional researchers from Western contexts, in this case the University of Melbourne, working with teacher educators and their trainee teachers at the Higher Colleges of Technology in the UAE. Thus, while each of the ARUAE projects is classified as SA (Ts working alone), the overall project would be classified as PRCGT (professional researchers working collaboratively with grassroots teachers).

Table 2. Classroom environment issues

Discussion of Data in Tables 1 and 2

As predicted, the main focus of the research topics for this group is Teacher methodology: 18 (42%) out of the 41, with 17, exactly 50%, of the topics classifying in this category in the case of PROFILE. Thus, the practice of action research for the PROFILE teachers is fundamentally aimed at teacher professional development. In the case of ARUAE, the picture is somewhat different, with only one topic in this subcategory. The focus on methodological issues has, in terms of five out of the six ARUAE topics (83%), wider implications for the curriculum. This is perhaps due to the fact that all of the ARUAE research was carried out at the PS level, where it is hard not to integrate methodology with wider curriculum issues. It may also be an outcome of the collaboration with the researchers (see Comments on data above) but this can only be confirmed through further research. That Curriculum is the second biggest subcategory for the Colombian and the first for the UAE researchers, seven and five respectively, is encouraging as this makes the total for the curriculum-relevant topics 12 altogether, i.e., 29%. Furthermore, two of the Colombian topics in other categories (29, 31) have a strong relevance for the curriculum so this statistic of 29% is on the conservative side. Also worthy of note is the fact that of the seven curriculum-focused projects carried out by the Colombians, more than half, four, which is 57%, were carried out collaboratively, which could possibly be interpreted as an implicit recognition that collaboration is highly recommendable when addressing bigger issues (see Data analysis below).

It is, however, of concern that the topics selected by this group of researchers concentrate so markedly on two aspects of Environment Issues, with other elements, such as Time for instruction, Ts' FL competence, Testing programme, which contribute just as much to the teaching-learning processes, receiving very little or no attention. Even more perplexing is the fact that only two of the topics deal directly with commonly acknowledged major difficulties of grassroots EFL teachers. The data for Group 2 serves, on the one hand, to further compound this issue; on the other, to illuminate it.

Group 2 Data

These data were collected at the beginning, in the case of questionnaire 1, and at the end, in the case of questionnaire 2, (see Appendixes 1 and 2 respectively) of the final plenary of a day's symposium on action research. Not all the participants at the symposium were new to action research; some of them had already done at least one action research project and had published their reports in PROFILE or other journals, but judging by their enthusiasm for it (see Cárdenas, 2003), were open to further projects. Similarly, not all of the participants were drawn from PS and HS, although PS and HS teachers were in the majority. Detailed reporting and analyses of the data from this group will form the bases of at least one other article on teachers' choices of topics for their potential action research projects. Here it is used solely to triangulate and expand on the discussion of the data collected from Group 1.

Areas of Difficulty: Data Questionnaire 1

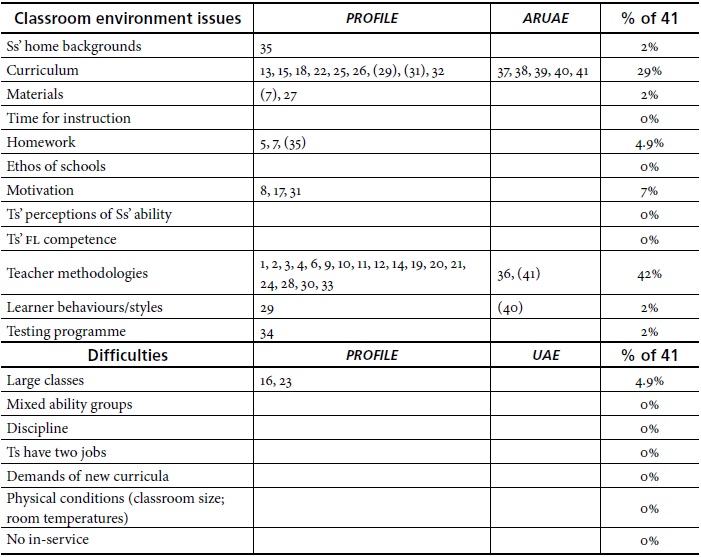

Altogether 89 copies of questionnaire 1 were distributed. Respondents were given a number by the monitors who distributed the questionnaires and asked to register the number in the space provided on questionnaire 1 and to memorize their number, or write down their number, as they would need it again at the end of the plenary. Respondents were given seven minutes to complete the questionnaire, the main aim of which was to check for the most common and salient difficulties for the symposium participants, most of whom work in similar contexts to those of the PROFILE researchers (Group 1). 83 questionnaires were returned. Only 47 respondents filled in item 12 but the percentages given in Table 3 for this item is based on 83 respondents as, in not responding, the other 36 participants were by omission registering a 0 rating for other sources of difficulties.

For this study, ratings 8-10 were interpreted as 'very difficult;' 5-7 'difficult'; 3-4 'not very difficult'; and 0-2 'not at all difficult'. Of interest here are the four items in questionnaire 1 which the highest number of respondents rated as 'very difficult' and the three most common additional difficulties they identified in item 126. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Most difficult aspects of teaching situations

Comment on Results for Questionnaire 1

What is most striking about these results is the very high number, 62 out of 83, (74%) who identify their own language ability as a major source of difficulty; this identification, however, was not an area of action research for Group 1 researchers even though the PROFILE researchers come from the same teaching environment. Yet, Stenhouse (as quoted by Elliott & Ching-Tien above) was clear that action research could help teachers improve not only their teaching practices but also their competence in the subject matter they taught. Just as striking are the reasonably high ratings, 42% and 35%, given respectively to items 6 and 9, which could be seen as two sides of the same coin: pupils' affective problems and lack of interaction between the school or teachers and parents. In the data for group 1, only one of the research projects (35) addresses the issue of pupils' backgrounds. Large classes posed a predictable major difficulty which was given a high rating by 28 (34%) of this group but again it gets scant attention in Group 1 with only two projects, 16 and 23, addressing this issue.

For additional sources of difficulty (item 12 in questionnaire 1), nine (11%) out of the 47 who answered this item identified 'time' as problematic in the sense that the time allocated to instruction is too short in their contexts. Yet, none of the action researchers in Group 1 focused on this aspect of their teaching even though it could lend itself to a variety of action research projects, such as maximising time through homework tasks, collaborating with teachers of other subjects in the reinforcement of knowledge, and more obviously using the Internet7. Specific aspects of teacher methodology, for example, how to use games in the language classroom, were identified by 7 (8.4%) of the respondents as another source of difficulty under item 12. This echoes the data for Group 1, but to a much lesser degree,where 50% of the topics were drawn from this source. Not enough opportunities to use English in the outside community also got a rating of 8%, which could serve to point future teacher researchers in the direction of another very useful action research topic.

Potential Topics for Action Research Projects Group 2

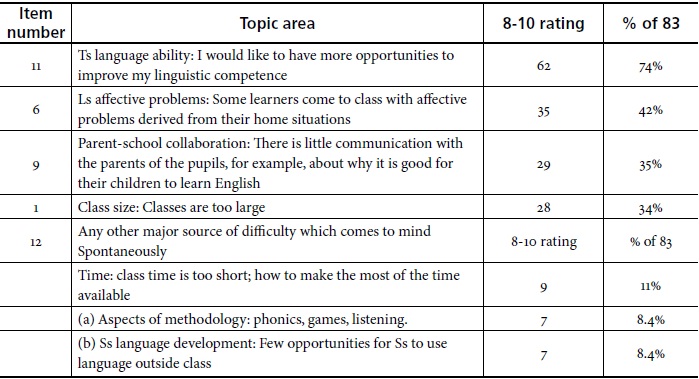

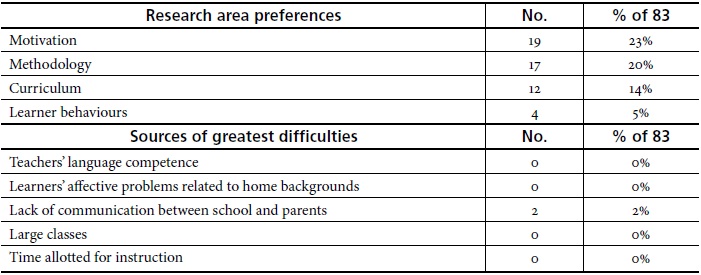

These data were generated by questionnaire 2 (open-ended), which was completed at the end of the plenary. Section 1 of Table 4, Research area preferences, reports the data relevant to the four most popular potential areas of research. Section 2, Sources of greatest difficulty, contains the data for the number of respondents to questionnaire 2, whose research preferences reflected the seven areas of greatest difficulty identified by the same group of respondents at the beginning of the symposium (Table 3).

Comparisons of Table 4 with Table 2

Nineteen (23%) of the Group 2 respondents (see Table 4 above) said they would like to do research on aspects of learner motivation, whereas only 3 (7.3%) selected motivation as a research focus in Group 1 (see Table 2). This may be because Group 1 respondents had more experience as teachers and had already sorted out their problems with learner motivation. It is worth pointing out, however, that many of the motivation topics for Group 2 were methodology-oriented, as in Motivating Learners through Songs. With respect to teachers' methodologies, 17 (20%) of Group 2 respondents said they would opt for a topic in this area, the second favourite topic source, but not as large as in Group 1, where it was the most common source of topics: 42% (see Table 2). With respect to the Curriculum, the gap between the two groups is smaller: 29% of Group 1 respondents opted for research into curriculum matters, while 12 (14%) of Group 2 respondents identified it as their preference; a difference of 15%. It is in Learner Behaviours where the gap is smallest with 2% of Group 1 opting to do research in this area and 4% in Group 2 identifying it as their preferred area of potential research but both of these percentages are very low indeed.

Table 4. Results for questionnaire 2 relevant to Tables 2 and 3

Comparison with Table 3: Although 76% had, at the beginning of the plenary, identified their own language competence as an area they needed help with, no one (0%) selected research into ways of improving their command of English as a possible choice of topic. Likewise, no one (0%) opted for a topic related to their learners' affective needs even though 42.1% had selected this as a major problem area in their teaching context. Two (2.4%) said they would do research into parental involvement with the school but as many as 34.9% had identified it as a major source of difficulty. Very surprisingly, no one expressed an interest in doing research into large class teaching. Similarly, although time allotted for instruction had been identified as the most common additional source of difficulty (11%), no one (0%) said they would opt to do action research in this aspect of their teaching either.

Discussion and Analysis of Data

Although this is a small study, certain patterns of teacher behaviour with respect to their action research emerge for these two groups. These are reflected in the answers to the original research questions:

a) To what extent, if any, are the teachers in this study being empowered through their action research activities?

Clearly, teachers in Group 1 have been empowered inasmuch as they have taken control of their own teaching practices and endeavoured to improve them through their own research. They have taken a big step away from the mainstream dependency grassroots teachers showed for so many years when attempting to improve their practices exclusively through the application of the results of research carried out in contexts different from their own. Empowerment could also be seen to be enhanced by the fact that these teachers have not only done their own research, but have published it too. This, as reported above, has added to their feelings of self-worth (raising self-esteem) which, in turn, will no doubt have positive effects on their self-confidence as teachers, hence, a positive effect on their teaching performances. It would seem unwise, however, to limit the empowerment of teachers to the narrow sphere of teachers' immediate professional development. Empowerment as proposed by Freire (1969) and clearly embraced by Stenhouse (see discussion above) goes beyond this interpretation into the realm of the profession as a whole, the realm of the greater good. Dewey, Lewin, and Stenhouse, as discussed above, were concerned that teachers would be instrumental in moulding the knowledge base upon which their professions as a whole are built, and in promoting general change.

In essence, action research typifies a grassroots effort to find answers to important questions or to foster change. Most important, action research can support the call for transformative educational leadership (Grogan, Donaldson, & Simmons, 2007, p. 2).

Again, inasmuch as these teachers have generated knowledge relevant to their actual grassroots circumstances, there is scope for such moulding and change to take place. Whether or not mainstream TESOL will accommodate this knowledge is another matter and the extent to which this is, or is not, happening is a question for future research projects. It is important to note, however, that now that teachers have generated such knowledge, the onus for accommodating it into mainstream TESOL is on the shoulders of mainstream educators and not on those of the grassroots teachers -or their educators. Their responsibility is to ensure that their research addresses all the issues which impinge on their teaching and this leads us to the next question.

b) Is the research, as practised by the active researchers, or as would be practised by the potential researchers, comprehensive? In other words, does it (would it) address a wide spectrum of the factors influencing and challenging teaching and learning in their situations?

On the one hand, need for improvement in the subject matter (EFL), the affective needs of the learners, lack of parental involvement with schools, mixed ability groups, large classes and insufficient time allotted for instruction are identified either in the literature review or by Group 2, or both, as major sources of difficulty. Yet, there appears to be a tendency for both groups to shy away from choosing topics related to these issues in their action research projects. It is, therefore, very hard to make a claim that, at this point in the history of the action research of these grassroots teachers, they are addressing all the questions which they find challenging in their specific context. This is true also of the researchers for the ARUAE publication. Although they do focus on wider curriculum issues, the topics all derive from an interest in methodology and general methodology issues are only one aspect of the curriculum; thus, there is still an imbalance in the distribution of the topics. Difficulties common to the UAE teaching context8, mixed ability groups, the issue of dealing with culturally alienating EFL materials, the testing programmes, for instance, are not addressed. There is on the part of both contingents in Group 1, however, what would appear to be a nascent interest in taking their research beyond their immediate classroom into the wider TESOL context (see Curriculum for both the PROFILE and ARUAE researchers in Table 2).

That these researchers eschew in their choice of research topics some of the major difficulties they themselves identify may have several explanations. First, they may feel intuitively that they need help with addressing major challenges. Second, the examples of action research they have been exposed to in the literature may, for the most part, have been strongly oriented towards methodology issues. Thus, the need for mainstream TESOL to recycle those research projects from the grassroots which address other issues of concern in the grassroots realm is even more pressing. Third, inasmuch as all of these researchers are developing in their field, although some more so than others, it may be that their choice or preference of topic has been made or expressed in line with how they see the future outcomes. In other words, while finding their feet as researchers, they, not unreasonably, want to tackle a problem with which they will have a measure of success, and therefore, avoid more complex issues.

c) Is the action research carried out not only for the teachers' professional self-development but also for the greater good i.e. for the community of TESOL educators and learners as a whole?

If teachers are improving in their individual practices as a result of action research, then clearly the greater good is being served as the profession as a whole is benefiting from better teaching. There is also evidence, in both the PROFILE and ARUAE contingents in Group 1, which would appear to indicate a nascent concern for bigger issues. It would be hard to claim, however, that, as yet, grassroots action research as represented in the choice of topics and topic preferences of these groups is generating in terms of their knowledge and that of the mainstream 'a dialectic tension ... an open atmosphere where inputs from each perspective could challenge and stimulate the other' (Kolb, 1984, p. 10). That grassroots researchers have taken the first major steps in a process which will help them influence the profession as a whole is undeniable. It behoves them at this point to reflect on their choices of research topics in order to ensure that they are not in fact endorsing the knowledge from, and concerns of, the dominant groups as it is the very problem of the top-down flow of knowledge which action research is supposed to resolve.

d) Is there evidence that teachers or professional researchers and teachers work collaboratively on their action research projects?

There is and this is one of several encouraging outcomes of this study. The ARUAE is a welcome and valuable example of international collaboration between teacher trainers and trainee teachers and that collaboration appears to have contributed to the success of the project. As for the PROFILE researchers, there is a clear tendency to do action research with colleagues, with 17 out of the 35 Colombian researchers, that is, exactly 50% opting to do their research with at least one colleague. Interviewing the collaborators, both for the ARUAE and PROFILE about the strategies employed for, and benefits of, the collaboration could provide more important insights into this aspect of grassroots action research in TESOL and would help prepare the ground for the collaboration which appears to be needed to address those problems which, because of their exigencies, these action researchers seem to be avoiding.

Concluding Comments

This study is itself not without problems. First, had circumstances permitted, interviews with the respondents to questionnaires 1 and 2 would have provided their specific answers to some of the questions this study poses, for example, "Why are some obvious areas of research being avoided?", and not limited the answers to mere speculation on the part of the author. Second, a full tally of the articles published in PROFILE so far might have resulted in a more favourable balance between topics derived from methodology and those from other areas. Third, interviews with the international collaborators of the ARUAE publication could have provided some useful benchmarks for future collaboration in other contexts. Despite these problems, it is hoped that the study has at least sparked some interest in the issues discussed, as synthesised below.

That most of the grassroots teachers in this study did not, or do not aspire to, research topics which they identify as representing major sources of difficulties is, on the one hand and for the reasons discussed in the analysis of the data, a source of concern; on the other hand, these data may harbour an implicit message from grassroots teachers to the TESOL community in the sense that, to research the bigger issues, grassroots teachers need help: help from professional researchers, from the institutions within which they work and the government departments who encourage them to do action research. This help was provided in the case of the ARUAE publication, and with laudable results. Even the ARUAE researchers, however, appear to view methodology as the main point of departure for their action research endeavours. That this might be the result of the focus of their teacher development programmes serves to alert teacher educators to the need to check that the examples of action research projects to which they expose their trainees derive from a wider scope of topic sources and teaching contexts. In this way, teachers should come to realise that action research is a way of attempting to mitigate all obstacles in their environment (Dewey); for example, overcoming problems with competence in the subjects they teach. It is also important that the problem solving aspect of action research is not sidelined in favour of the mere practising of a procedure and that grassroots researchers become aware that they can, should, and have a right to influence the profession as a whole through finding their specific solutions to problems.

Finally, this study is not to be understood as a criticism of the action researchers and potential action researchers whose research topics and topic preferences are at the core of the discussion. Despite identifying areas of concern, the study celebrates the outstanding achievements of the researchers in Group 1 and the enthusiasm and interest of those in Group 2. The progress in grassroots EFL teachers' action research has, over the past decade, been quite remarkable; in 1999, few applied linguists would have believed that publications like PROFILE and ARUAE would ever materialise, let alone progress and develop -as is the case with PROFILE. The credit for this progress goes first to the researchers themselves, many of whom work in extremely difficult circumstances, to the determined efforts of the teacher educators, and, in the case of ARUAE, to their institutional and international collaborators. It is hoped that this study will inspire other professional researchers to offer similar assistance to grassroots teacher researchers as the data analysis would seem to indicate that grassroots researchers find it too daunting to deal with the complex issues on their own. The tone of much of the literature on action research in TESOL is one of uncritical enthusiasm which can, in the long term, be counterproductive. This study is to be interpreted as a stock-taking exercise of what is being achieved in the field, serving principally to flag up areas which require some thought, attention and even reorientation to help keep the ship on course.

1 This study does not enter into debate about whether action research is or is not a theory in scientific terms; theory here is being used in its most general sense as a set of principles.

2 The collaborative-collective distinction, which some theorists insist on (see Winter, 1996, p. 228), is not considered essential or even all that useful to this discussion.

3 See Smith 2001 for the circumstances under which Lewin 'discovered' the benefits of two-way discussion and debate in teacher training when the trainees themselves asked for permission to sit in on the discussions of their performances.

4 See Winter 1996 for the full list of principles he proposes.

5 The data not discussed here are being used in articles which are forthcoming at the end of 2010.

6 As noted earlier, the remaining data for these two questionnaires will be processed in another/other articles as here there is insufficient space to analyse these data in full.

7 In the United Arab Emirates and in the main cities in Colombia, most PS and HS now have access to Internet facilities and where they do not have access in the schools in Colombia they have it at home.

8 Having worked in this context, the author is familiar with the challenges.

Documents Consulted

Action Research in English Language Teaching in the UAE. A. Warne, M. O'Brien, Z. Syed, M. Zuriek (eds.) Abu Dhabi: Higher Colleges of Technology Press.

[ Links ]PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 1, 2000. M. L. Cárdenas (ed.), Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Human Sciences Faculty, Bogotá.

[ Links ]PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 2, 2001. M. L. Cárdenas (ed.), Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Human Sciences Faculty, Bogotá.

[ Links ]PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 6, 2005. M. L. Cárdenas (ed.), Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Human Sciences Faculty, Bogotá.

[ Links ]PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 7, 2006. M. L. Cárdenas (ed.), Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Human Sciences Faculty, Bogotá.

[ Links ]PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 10, 2008. M. L. Cárdenas (ed.), Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Human Sciences Faculty, Bogotá.

[ Links ]PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development 11(2) 2009. M. L. Cárdenas (ed.), Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Human Sciences Faculty, Bogotá.

[ Links ]References

Appel, J. (1995). Diary of a language teacher. Oxford: Macmillan Heinemann.

[ Links ]Barrow, R., & Woods, R. (1988). An introduction to philosophy of education (3rd edition). London and New York: Routledge.

[ Links ]Caillods, F., & Postlewaite, N. (1989). Teaching/learning conditions in developing countries. Prospect, 14(2), 182-190.

[ Links ]Cárdenas, M. (2003). Teacher researchers as writers: A way to sharing findings. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 5, 49-64.

[ Links ]Clark, J.L. (1987). Curriculum renewal in school foreign language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[ Links ]Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research methods in education (5th Edition). London and New York: Routledge and Falmer.

[ Links ]Dewey, J. (1923). How we think. London: D. C. Heath & Co.

[ Links ]Dewey, J. (1977). The middle years, 4, (1907-1909). Carbon-dale: Southern Illinois University Press.

[ Links ]Dimitriadis, G., & Kamberelis, G. (2006). Theory for education. New York London: Routledge.

[ Links ]Elliott, J., & Ching-Tien, T. (2008). What might Confucius have to say about action research? Education Action Research, 16(4), 569-578.

[ Links ]Freire, P. (1969). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder & Herder.

[ Links ]Grogan, M., Donaldson, J., & Simmons, J. (2007, May 19).Disrupting the status quo: The action research dissertation as a transformative strategy. Retrieved from the Connexions Web site: http://cnx.org/content/m14529/1.2/

[ Links ]Hassanova, D., & Shadieva, T. (2008). Implementing communicative language teaching in Uzbekistan. TESOL QUARTERLY, 42(1), 138-143.

[ Links ]Kachru,Y. (1985). Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: The English language in the outer circle. In R.Quirk & H. Widdowson (Eds.), English in the world: teaching and learning the language and literature (pp. 11-30). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[ Links ]Kamarul Kabilan, M. (2007). English language teachers reflecting on reflections: A Malaysian experience. TESOL QUARTERLY, 41(4), 681-706.

[ Links ]Kemmis, S. (1995). Some ambiguities in Stenhouse's notion of the 'the teacher as researcher': Towards a new resolution. In R. Jean (Ed.), An education that empowers (pp. 73-111). Clevedon, Philadelphia, Adelaide: Multilingual Matters Ltd..

[ Links ]Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (Eds.). (1992). The action research planner (third edition). Geelong, Victoria, Australia: Deakin University Press.

[ Links ]Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning. Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

[ Links ]Lewin, K. (1946). Research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2, 34-46.

[ Links ]Lewin, K. (1948). Resolving social conflicts; selected papers on group dynamics. Gertrude W. Lewin (Ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

[ Links ]Lewin, K. (1952). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers. London: Tavistock Publications.

[ Links ]Mertler, C.A. (2009). Action research (second edition). Los Angeles, London, New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

[ Links ]Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[ Links ]Prodromou, L., & Clanfield, L. (2007). Dealing with difficulties. England: Delta Publishing.

[ Links ]Riddell, A. (1999). Evaluations of educational reform programmes in developing countries: Whose life is it anyway? International Journal of Educational Development, 19(6), 383-394.

[ Links ]Saud, U., & Johnston, M. (2006). Cross-cultural influences on teacher education reform: Reflections on implementing the integrated curriculum in Indonesia. Journal of Education for Teaching, 32(1), 3-20.

[ Links ]Senior, R. M. (2006). The experience of language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[ Links ]Smith, M.K. (2001).Kurt Lewin, groups, experiential learning and action research, the encyclopedia of informal education. Retrieved from http://www.infed.org/thinkers/et-lewin.htm

[ Links ]Somekh, B. (2006). Action research: A method for change and development. Buckingham: Open University Press.

[ Links ]Stenhouse, L. (1975). An introduction to curriculum research and development. London: Heinemann.

[ Links ]Stringer, E.T. (1999). Action research (second edition). Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

[ Links ]Winter, R. (1996). Some principles and procedures for the conduct of action research. In O. Zuber-Skerritt (Ed.). New Directions in Action Research (pp. 13-27). London: Falmer.

[ Links ]Zappa-Hollman, S. (2007). EFL in Argentina's schools: Teachers' perspectives on policy changes and instruction. TESOL QUARTERLY, 41(3), 618-625.

[ Links ]About the Author

Isobel Rainey has worked in the UK, South America, and the Middle and Far East as an EFL teacher, lecturer in Applied Linguistics and textbook writer. Her main research interest concerns the teaching of EFL in challenging circumstances. She is currently member of the GESE/ISE panel for Trinity College London.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions during the process of publishing this article. Any errors are of course mine alone.

Appendix 1: Questionnaire Used at the PROFILE Symposium to Inquire

about the Difficulties Teachers Encountered in their Current Teaching PositionsPROFILE Symposium

FIRST ACTIVITY

Number: ___________________

On a scale of 0 (does not apply at all) to 10 (applies 100%), rate the extent to which each of the following statements applies to your particular teaching circumstances. Do not attempt to put the statements into an ascending order of applicability.

- Classes are too large: ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- The range of levels/abilities in each class is very wide: ____________________________________________________________________________________________________

- There is not enough money to buy appropriate resources (teaching materials and aids): ___________________________________________________________________________

- There are serious problems with discipline in some classes: ________________________________________________________________________________________________

- The motivation to learn English of some students/groups is very low: _________________________________________________________________________________________

- Some learners clearly come to class with affective problems derived from their home situation: ______________________________________________________________________

There is little enthusiasm on the part of the school/institution for innovations to teaching or the curriculum or for action research: _____________________________________________- Few teachers of other subjects are interested in working collaboratively to change teaching/learning approaches: ________________________________________________________

There is little communication with the parents of the pupils e.g. about why it is good for their children to learn English:_____________________________________________________- I have to hold down two jobs to make a living and that limits the time I have to think about and research major sources of difficulties in my classes: _______________________________

- I would like to have more opportunities to improve my linguistic competence: ______________________________________________________

- Any other major source of difficulty (just one) which comes to mind spontaneously:

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

(Please rate):

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Appendix 2: Questionnaire Used at the PROFILE Symposium to Ask

Teachers Which Topic They Would Choose, Should They Be Given a Chance to Do Action ResearchPROFILE Symposium

SECOND ACTIVITY

Number: _______________________

Now that you have attended this talk, take a few minutes to think about an aspect of your teaching experience which you would like to research (through action research):

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________