Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

versión impresa ISSN 1657-0790

profile v.14 n.1 Bogotá ene./jun. 2012

Adolescent Students' Intercultural Awareness When

Using Culture-Based Materials in the English Class

La conciencia intercultural de estudiantes adolescentes al usar materiales

con contenido cultural en la clase de inglés

Mireya Esther Castañeda Usaquén

Secretaría de Educación de Bogotá, Colombia

mire_@hotmail.com

This article was received on February 20, 2011, and accepted on October 30, 2011.

This article reports on a qualitative and interpretative case study conducted at a high school located in the southeast of Bogotá. The case is comprised of a group of fifty-one eighth graders who had had little contact with English. It aimed at exploring how these adolescents made sense of the culture-based materials implemented in the English lessons, and at describing their perceptions about foreign cultures. Video and audio recordings, surveys, field notes and students' artifacts were used to collect data. In this article, teachers can find some materials and reflections upon cultures as well as some ideas on how they can be adapted to their own needs and/or teaching contexts.

Key words: Culture, culture-based materials, foreign culture, home culture, intercultural awareness.

En este artículo se reporta un estudio de caso de tipo cualitativo e interpretativo que se realizó en un colegio público del suroriente de Bogotá, con un grupo de cincuenta y un estudiantes del grado octavo, quienes tenían poco contacto con el idioma inglés. El objetivo fue explorar cómo estos adolescentes entendían los materiales con contenido cultural usados en las clases de inglés y describir sus percepciones de las culturas extranjeras presentadas en los materiales. Se recolectó información mediante grabaciones de video y audio, encuestas, diario de campo y material elaborado por los estudiantes. En este artículo, los profesores pueden encontrar materiales y reflexiones sobre culturas y adaptarlos a sus necesidades o contextos.

Palabras clave: conciencia intercultural, cultura, cultura foránea, cultura materna, materiales con contenido cultural.

Introduction

What people say every day is shaped by their knowledge, background, and experience, among other factors. English teachers must be aware of some cultural differences or similarities between our students' language and culture and what they learn in our classrooms, a foreign language and culture. As students use English only in the classroom I prepared and implemented materials which help them to broaden their views of the world. This study purports exploring students' knowledge about culture, finding out the relationship between the culture-based materials implemented in the lessons and analyzing students' perceptions about culture in a semi-rural state school with large classes. In order to fulfill the objective, the questions shown in Figure 1 were posed.

Conceptual Framework

Culture

Damen (1987), Robinson (1988), Freire and Macedo (1987), Storey (1996), Roth and Harama (2000), Nieto (2002), McLaren (2003) and Dolby (2003) agree with the conception that culture is complex, is dynamic, and is influenced by many factors because it is the center of human relationships. Nieto (2002) affirms that "everyone has a culture because every person participates in the world through social and political relationships informed by history as well as by race, ethnicity, language, social class, sexual orientation, gender, and other circumstances related to identity and experience" (p. 10). McLaren (2003) points out that culture is understood as "the particular ways in which a social group lives out and makes sense of its 'given' circumstances and conditions of life" (p. 200). In addition, Kramsch (1999) stresses that the perceptions that we have about foreigners are determined by the culture that we belong to.

For this study, culture is defined as the way eighth graders interpret and understand what happens in English classes because they expressed their perceptions of their native culture, and the foreign cultures. I explored what they conveyed with their messages about those cultures during the lessons.

In relation to school, Nieto (2002) states that comprehending a culture entails "an understanding of how students from diverse segments of society -due to differential access, and cultural and linguistic differences- experience schooling and a commitment to social justice" (p. 4). Since the school was located in a marginal area of the city, and pupils' socio-economic conditions were restricted, it was fruitful to see the different visions students had of the classes when they used the materials. Students' background and the perceptions generated by their interaction with materials were crucial aspects that shaped students' understanding of their home and the foreign culture.

Materials

Tomlinson (1998) defines materials as something that teachers and pupils use to make the experience of learning a foreign language easy; and as "anything which is used by teachers or learners to facilitate learning of a language. (...) It can be everything, which is deliberately used to increase the learners' knowledge and/or experience of the language" (p. 2). Both teachers and learners can be materials developers, but when studying cultures teachers have to ask about the sociocultural aspects that materials presented involve because "No society is a single seamless entity made up of 'standard' members" (Tudor, 2001, p. 73).

Going beyond, authors such as Storey (1996) and Roth and Harama (2000) gave a hint for finding sources with cultural content because from their perspective culture can be picked up from everywhere. Roth and Harama (2000) affirm that teachers "need to consider the world as a text, so that literacy means engaging the full range of what we can find in the library, art gallery, and the street" (p. 771).

In relation to the classification of materials, Cárdenas (2000) refers to two kinds of materials depending on the public they are directed to: materials for a local audience and commercial materials, which are for a large audience. She describes a 10-stage procedure that a team she worked with followed in order to produce materials to respond to children's local needs. She also explains some of the principles that they kept in mind when designing and evaluating the materials. They took into account learners' needs, the relation between teaching materials to schools' aims and objectives, the variety in class arrangement, and the connection between language, the learning process, and the learner. Finally, she asserts that if a book suited students' needs, interests, and abilities, suited the teacher, met educational policies, and was flexible enough to be used it would be the best book available for teacher and students.

Cortazzi and Jin (1999) establish three groups of materials according to the role of the cultural content and information in them. The first one is source cultural materials which draw on learners' own culture content. The second one is target culture materials which exploit the culture of a country where English is spoken as the first language. The last one is the international target culture materials which take advantage of resources from different countries not only the English-speaking ones.

Pedagogical Design

I used some criteria proposed by Cortazzi and Jin (1999, p. 203) to evaluate textbooks with cultural content. I organized the tasks implemented in the classroom according to the parameters shown in Table 1, which gathers the criteria connected to culture and the tasks. Then, I explain each of the lessons, the roles of students and the teacher, the steps followed, and their relationship with culture.

For the first criterion, social identity and social groups, students read about a real situation lived by a group of people in New York. This is not widely known and I have to confess that I did not know anything about that. So, I also learned about a group in deprived economic conditions in the USA.

For the second criterion, social interaction, students saw London through an educational video. They could hear some colloquial and formal expressions in different locations in the center of London such as cafes, bookshops, the underground, etc. The main focus of this video was to show the city as a place where one can find lots of facilities. Students listened to formal language when the actors asked for something and informal language when they talked friendly to each other. It is important to say that one of the characters was a tourist and the other was a native speaker.

The third criterion, belief and behavior, was worked because most of the students manifested being mistreated at home and complained of a lack of affection inside their family life. So, I illustrated the same situation lived by large numbers of people, including North Americans through a TV program called "Jerry" which, that day, presented a problem between a man (stepfather) with two teenagers (stepsons) and his wife (teens' mother). This program was moving for students, and it helped them reflect on aggressive actions, on the use of rude words, and also on their roles as sons and daughters.

The fourth criterion, social and political institutions, was addressed through a reading on the Buckingham Palace. This text showed the Queen's life in her palace. Some aspects of the British government were introduced, which are different from North American and Latin American societies.

For the fifth criterion, socialization and the life cycle, pupils watched two social events: one was in a real classroom and the other took place during a school party. Those situations touched pupils' lives because they had watched such moments as they happened: since the video was not edited, they could have a clear picture of North American students, their same age and grade (8th). Adolescents could see how foreigners behaved in at least two familiar settings: a classroom and a school party.

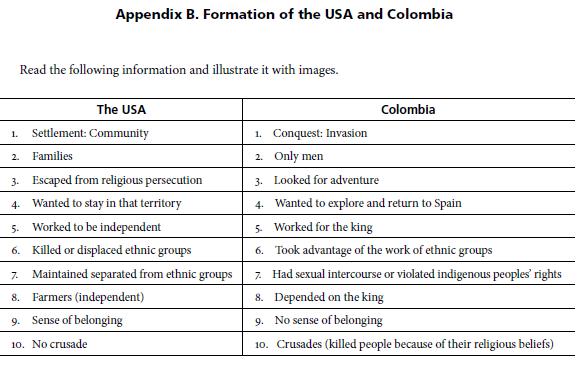

For the sixth criterion, national history, I included readings and tasks related to historical events that explained facts about some nations' formation and identity. One of those readings described how Great Britain was settled and the other was a book in which the foundation of each state of the USA was explained.

Figure 2 shows some excerpts from a pupil's notebook. They show the student's drawings to illustrate some facts about the settling of Colombia and the USA.

For the sixth criterion I also created and implemented a task that included a cultural product like currency (bills, coins), and followed some steps: In the first, students were given some dollars and they pretended to sell and to buy some souvenirs (brought by them from a tourist place where they had been). Then, they completed a table, including the products they had sold, and the customers' names. In another task, I provided pupils with a photocopy from a worksheet I myself designed which contained some historical facts of the people who were printed on the bills, and they looked for the prize that corresponded to that person. Then, as homework, students took the same information from Colombian bills. Thus, students not only learned about American history but also about Colombian history by recognizing significant people from foreign and native cultures.

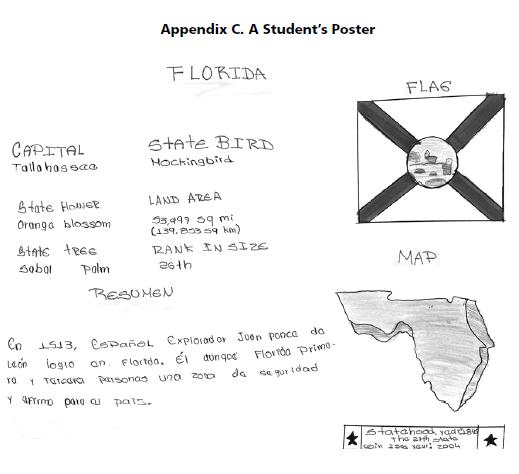

For the seventh criterion, the national geography, students read texts about the founding of the states (USA) and departments (Colombia), drew some maps and included the most significant information about them.

For the last one, stereotypes and national identity, teenagers read texts about typical foods, sports, and symbols in the USA and the UK. In one of the lessons students saw a video about tea, and in another they drank tea. Students gave some oral presentations based on some excerpts about holidays in North America and in the UK.

Finally, during the last lessons, pupils wanted to give a presentation; most of them chose something in the fashion of popular singers such as Shaggy and Madonna. The teenagers seemed to enjoy their presentations and the audience was attentive.

Materials

A detailed description of the materials used for each lesson, the name of each lesson, and the list of sources used during the instruction is provided in Table 2. I adapted a lesson of the book called Cultural Awareness by Tomalin and Stempleski (1994), and designed tasks using some of the following resources: magazines, newspapers, songs and their lyrics, photos, videos, maps, two home video clips -one of an American classroom, a party at a school1, an American TV program; two educational videos, one about London and the other about tea- some currency of the USA, Britain and Colombia, readings from textbooks (see Table 2) and CDs brought in by students.

Research Design

This is a qualitative, exploratory and interpretative case study (Larsen-Freeman, 1991) carried out with the whole class over ten months. Observation was naturalistic because students were recorded. This is a case study because "it gives an opportunity for one aspect of a problem to be studied in some depth within a limited time scale", and the data are collected in a systematic way (Bell, 1999, p. 10).

Participants

Bogotá is a place where one can find diverse realities. It is very different to teach in a school located in an urban area than in one in the periphery. This project was conducted in 2003 with a group of eighth graders at a public school located in the southeastern part of the city. In this neighborhood there were not any banks, cinemas or malls, so the community had to go to other neighborhoods to get some goods and services. People belonged to zone one of the local socioeconomic stratification. The classes were large, with about fifty-one students in each group. Students had two sessions of English class a week, one of 110 minutes, and the other of 55. Students were at the elementary level of English. Their ages were between 11 and 16.

Data Collection

I used surveys, field notes, audio and video recordings, and students' artifacts. According to Bell (1999), the main purpose of a survey is to find out information which can be analyzed to identify patterns (p. 13). Surveys were administered to the whole class in order to explore students' knowledge, perceptions, opinions, and reflections of home and foreign cultures and of the materials used. Besides that, at the end of the lessons semi-structured interviews were administered to some students of the class. "These interviews are guided by a list of questions or issues to be explored, but neither the exact wording nor the order of the questions is determined ahead of time" (Merriam, 1988, p. 74).

Because of the noisy setting, I took the tape recorder with me all the time. I set the camera in one of the corners of the classroom and placed a tape recorder in a group that was not being captured on camera. I recorded what students said "verbatim quotes, in your students' own words" (Hubbard & Power, 1999, p. 95). I also took field notes regarding students' comments about culture. Finally, with the students' artifacts I gathered evidence of what students did during the lessons, and what they learned from the lessons.

Data Analysis

To analyze the data I followed the open coding procedure (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). First of all, I read and re-read the data in order to find commonalities. Second, from these common attributes I read again to find patterns; the ideas that I found were grouped into subcategories according to the characteristics shared.

I read students' answers in the surveys and tried to find patterns. Next, I labeled the subcategories; then I numbered each page; and finally, I designed a chart where I indexed students' verbatim dialogue by indicating date of the lesson, page number, question number, and the name of the group those words represented. I transcribed the tapes (audio/video) and used color-coding for the video and tape transcriptions. I highlighted in different colors the ideas that supported the commonalities I found. I also used symbols next to the line that caught my attention and, at the end of the transcription, wrote commentaries, questions, headings and thoughts.

I transcribed the semi-structured interviews and underlined in color the ideas that substantiated the categories identified in the other instruments. Then, a name was given to each category. After that, the data were read again and the patterns contrasted to establish the categories that emerged from the different instruments. Then I wrote the quotations or ideas from the data that helped illustrate the categories.

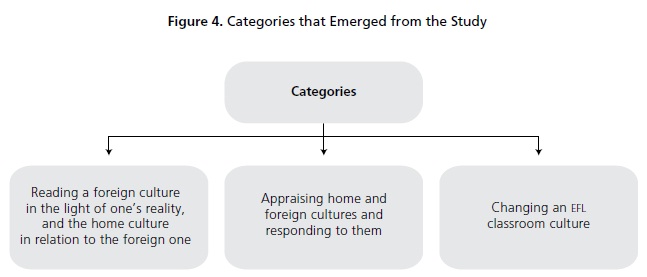

Findings

The categories depicted in Figure 4 were drawn from the data to explain students' intercultural awareness while interacting in class with culturebased materials.

Reading a Foreign Culture in the Light of One's Reality, and the Home Culture in Relation to the Foreign One

This category reflects the way students used their own world, their experiences, and their knowledge as a tool to read the foreign cultures presented in the materials, and reading home culture in relation to the foreign one. For Freire and Macedo, "Reading the world always precedes reading the word, and reading the word always implies continually reading the world (...)" besides that, "reading the word is not preceded merely by reading the world, but by a certain form of writing it or rewriting it, that is, of transforming it by means of conscious, practical work" (1987, p. 35). Students read the materials used in lessons following a path: First, they used the materials; then, they made sense of them, and finally they let me know their interpretations by sharing them through their writings, behaviors, and ideas. Students used their previous cultural knowledge and experiences, and their home culture characteristics, to understand, to read the foreign culture, and to establish links between the two cultures in contact.

Pupils read the foreign culture in the light of a very familiar feature of their home culture because after reading a text about Buckingham Palace, they found, as most of them did not have any spatial referent for this place, a referent in the city they live in, Bogotá; they also considered it very big, like Buckingham Palace. According to Dayana, Nicol and Xiomara: "in London there was a prime minister and a parliament, and that the palace was as big as a city" (Survey, Nov. 4th)2.

Another example was that Fernanda did not know that champeta is a Latin rhythm, so she associated it with hip-hop3. Hence, and since she did not like champeta, she concluded that "the parties in that foreign school were boring" (Survey, Nov. 4th)4.

In another lesson, teenagers watched a video about tea, but most of the students reported that they had watched a video about coffee. Beethoven: "about the history of coffee, how many times people drank coffee, and about the country where caffeine is drank the most" (Survey, Oct. 21st).

When I realized the misunderstanding, I made tea and pupils drank it, most of them had not drunk it before. Some students linked that new flavor with a very familiar drink in their diet. Nathalie: "tea shared a characteristic with a popular Colombian drink made from sugar cane, it was its color" (Survey, Nov. 12th). Thus, she compared the new with the old. She read the foreign culture in the light of her own reality.

Language is another aspect that played a role in students' interpretations of the foreign culture because when they wrote they used Spanish in a very peculiar way. For example, Carlos explained a situation experienced by some people in New York who lived in the undergrounds. He used a particular expression to mean that these people had to go away from the undergrounds: "pisarse" when the police came.

285. Ss: Railway.

286. T: Railway, and what else? Where do they live?

287. Ss: Tunnel.

288. T: Tunnels. Then, they

289. have to (rises her hand and shakes

290. her fingers to show that they have to go)

291. Carlos: Go away, go away. (Video transcriptions, Nov. 13th)

Regarding the use of language, Fabián said that American teenagers were yankees: "They are yankees". I asked him what he meant by yankee and he said that it meant "very tall" (Teacher's field notes). To analyze this example, I used Adaskou's assertion (1990, in McKay, 2000), which states that in the culture level denominated pragmatic sense, language learning has to do with cultural norms: whether an expression fits in a specific context. For Duvan and his group the word yankee had a shared connotation, which differed from mine, or from other groups'. When I looked at this expression I put the meaning of that word in a broader context, our Colombian one, where that word is used during workers' protests to refer to North Americans (yanquis). Because of Duvan's answer, I was sure that he did not know of the negative and political force that this word had. He was using an expression but it did not fit the context in which it was framed. Pupils reflected the images of the foreign culture through their native language and that matched Halliday's idea (1990) that language is a way of coming nearer to the world and making sense of it, and that language is a mirror of reality. In other words, the word "yankee" for this group referred to a very tall foreigner.

Fernando used an idiomatic expression when he described the video about London as a nice one:

46. Fernando: (reading the question aloud) What do you think of

47. the materials used in today's class? AJISOSOS.

48. I write ajisosos (talking to himself).

49. Duveimar: Wow!

50. T: A volunteer (to Fernando). What does ajisoso

51. mean?

52. Fernando: ajisoso.

53. Duveivar: WONDERFUL! NICE!

(Audiotape, Oct. 20th)

Participants used their average physical characteristics (short and thin) to comprehend the foreign culture. American students who were recorded in the video and the observers, Colombian students, had in common their ages (14-15), grade (8th graders) and context (a public school) but pupils wrote in the surveys that the main difference between them was the age. That idea did not correspond to the factual information, but that was the way they perceived that reality using the standards of height and weight in their home culture. Nicol: "Young boys looked very old" (Survey, Nov. 3rd) and Jhonpy said that he could see students of his same course, "that they were old between 16 and 18" (Survey, Nov. 3rd).

Students also contrasted foreign classrooms with the ones at home. Hemili explained that she learnt about rooms in the USA because "In the USA places are spacious while here places are cramped" (Survey, Nov. 3rd).

Danielewicz (2001, p. 59) states: "Our identities are manifested in what we regard as the self, the internal state of consciousness we refer to in everyday speech whenever we say I". Students manifested their social self because they used key words like we, our, I, or in Colombia to talk about themselves; and other words like there, they, in the USA, in order to contrast the home culture with the foreign one. I refer to social self in this document to the relations established between myself and others, or my country (Colombia) and the other societies (the USA and the UK).

Students contrasted their social selves with the foreigners'. For Collins (2000) the self-concept develops the self-image, the self-esteem, and the ideal self. Self image is defined as the individual awareness of his/her mental characteristics; selfesteem refers to the individual's evaluation of the discrepancy between her/his self-image and the ideal self, which is made up of the ideal characteristics he or she should possess, and ideal standards or skills and behaviours which are valued within the society in which she/he is growing up.

Besides that, Roth and Harama (2000) think that identity is an articulated premise of daily life, including schooling: students showed their identity when they talked about customs that characterize their culture. Collins (2000) affirms that identity involves the self-concept, which has three aspects: the cognitive (thinking), the affective (feeling), and the behavioral (actions). From my point of view the first one deals with the academic self, the second with self-esteem, and the third with the social self. Pupils revealed the concept they had about their social behavior.

After reading a short text called "Where do the British come from?", which presented the idea that British people were all immigrants, Xiomara found some correlation between the formations of both Great Britain and Colombia. She wrote: "It seems that there was not a slow conquest but invasion" (Survey, Oct. 3rd). The information she provided was the product of the connections she had made among news on TV (in those days the conflict between the USA and Iraq reigned), the situation of many Colombians being displaced or forced to resettle, and the content of the reading.

Regarding the role of mass media in students' view of the world, Dayana, Nicol and Xiomara read some paragraphs about Buckingham Palace and established a relationship between the White House in the United States, which they have seen on TV several times, and Buckingham Palace, and not with the Nariño Palace in Colombia. Apparently, students had not seen our palace before. That could be due to the fact that they rarely go out of their neighborhoods. Otherwise, students would have contrasted the palace in London with the palace in Bogotá. The White House was not mentioned in the reading. They reported what they learnt: "Here, in Colombia, there was a president and a White House" (Survey, Nov. 21st). Pupils gave attributes to their home culture that it does not have. They did that because they tried to apply knowledge transmitted by mass media and not with the information presented in the text. Willis, in Dolby (2003), argues, "popular culture is a more significant, penetrating pedagogical force in young peoples' lives than schooling" (p. 264). He also states that school has left aside its role in students' identity formation, which has been taken or assumed by the popular culture and mass media.

We can recapitulate from this category that students read their home culture in light of their own reality by using their previous knowledge, experience, and home culture characteristics such as language, physical characteristics, behaviors, and buildings. They also related their home culture to the foreign one by contrasting their social selves with the foreigners', and by making connections between the home culture and foreign cultures.

Appraising Home and Foreign Cultures and Responding to Them

To appraise is "to examine (someone or something) in order to judge their qualities, success or needs" (Cambridge international dictionary of English, 1995, p. 57) and response is understood as the "act or feeling produced in answer to a stimulus; reaction" (Oxford advanced learner's dictionary, 1993, p. 1077). Students not only read about the foreign and home cultures, but also responded to them critically. When students responded to the culturebased materials, they challenged home culture policies, acknowledged some aspects of the foreign culture represented in the materials, reshaped their home culture beliefs, expressed surprise, reshaped perceptions of the foreign culture, balanced the cultures, and valued the richness of their home culture. Some examples are the following:

In a lesson, after watching a video of an American school, Adriana stated: "In the school in Virginia (USA) there are things that we do not have in a Colombian public school. The government does not invest in public education." (Survey, Aug. 3rd) Beethoven read between the lines of this situation as he described the bad conditions of his own classroom, chairs that were like old sticks of wood and explained the role he saw of the American state in the maintenance of the American school:

19. "T: Well... Did you like the video?

20. Yes or no? And why?

21. Beethoven: Eh...Yes, I do. I liked the video because eh...

22. there we learnt eh, how, eh, the, the state

23. takes cares of the school very well.

(...)

30. T: Well, did you learn anything new about...

31. those aspects?

32. Beethoven: (Nods)

33. T: about what aspect you learned

34. Anything new?

35. Beethoven: of a classroom from a public school.

36. because, because we are

37. sitting on very old and destroyed desks

38. our classroom, and there, they have everything

39. modified, new. We do not have anything.

(Audio transcription, Aug. 22nd)

In another lesson, students read a short text of one state in the USA. There was a big map of the American continent on a table; Leonardo and Beethoven were looking at it. Teacher approached them and asked what they had seen. Beethoven answered that Colombia was very close to becoming a new state of the USA because we had debts with the World Bank. He also expressed that he did not like that situation because we would lose our beloved land:

113. T: What did you see on the map?

114. Beethoven: That we are near (points to the map)

115. T: What?

116. Beethoven: Being another state.

117. T: Why?

118. Beethoven: Because we have a debt with the World Bank.

119. T: What happens, don't you like it?

120. Beethoven: No, I do not. We lose our land.

(Audio transcription, Sep. 5th)

Students understood our Colombian social situation by using foreign policies as an excuse. This is what Freire and Macedo (1987), Storey (1996), Nieto (2002) and McLaren (2003) explained when they said that culture is a site of social differences. Teenagers drew conclusions of their own socioeconomic situations in light of politicians' decisions about investing money and placed the responsibility for the differences found between the foreign and home societies on the politicians.

When students used the materials they also reshaped their home culture values. When I read students' reflections I could recognize that the materials and the instruction exerted a certain kind of power which helped students expand their ideas about some essential values that help everybody live a better life such as environmental protection, dialogue, coexistence, and tolerance.

Pupils watched a video about the center of London. Horse manifested that he learnt "about the protection of the environment by taking care of everything and not throwing rubbish to rivers"(Survey, Oct. 20th). Students also read a short article about people who live in the undergrounds of New York. This reading caused Xiomara to reflect on "the importance of recycling, and of taking care of books, and keep them to sell in the future as a mean to survive" (Survey, Nov. 13th). It can be inferred that students were thinking about things they valued in order to have a better place to live in, as they saw in the video, and when they read the article, they realized that a place like that could be possible and reflected upon the actions they could take to build that better place. In that way, they evaluated their self-concept and manifested these possible actions to take care of everything in their worlds, recycling, not throwing rubbish into the water, or not throwing away books, in order to accomplish an ideal self. In fact, these are values expressed in the shape of actions to be carried out. Finally, self-concept and the ideal self were explored because students expressed some thoughts which allowed me to hear their ideas about protecting the environment and the importance of recycling.

The importance of conversing to live in harmony was also remarked on by students constantly. It seemed that to solve problems by talking is what pupils concluded as the best option, after having used the materials. Students watched a video, which contained a troublesome situation in a North American family.

Escarcha: "one must not be aggressive."

Fernanda: "I liked the activity. Males and females are aggressive and both used rude words, so we have to use proper words." (Survey, Nov. 21st).

When students used the materials they valued the richness of their home culture. Value is defined as "have a high opinion of somebody or somebody" (Oxford advanced learner's dictionary, 1993, p. 1411). Students found the worth of their home culture in relation to its music, famous people printed on the currency, and landscapes. In one task, students had to find information about the people who appeared on Colombian bank notes; the class shared their findings and compared them with the American dollars. The class expressed that on Colombian bank notes there was a variety of people who appeared printed on them while on the American ones there were only presidents.

13. T: What's the difference?

14. Ok. Rise your hand and say

15. (Points to a student)

16. Fabian: That most of them are

17. Liberators and the others can be eh.

18. can be male heroes

19. Nerón: Heroes

20. T: And what else?

(Video transcriptions, Sep. 3rd)

Damen (1987) says that "cross-cultural awareness involves uncovering and understanding one's own culturally conditioned behaviour and thinking, as well as the patterns of others. This process involves not only perceiving the similarities and differences in other cultures but also recognizing the givens of the native culture" (p. 141). I could state that students are in the process of raising intercultural awareness because in the data analyzed we have seen how they try to uncover and understand not only the similarities and differences between the cultures they are in contact with but also the qualities or richness of their own.

Changing an EFL Classroom Culture

Change is defined as "become different" (Oxford advanced learner's dictionary, 1993, p. 187), and classroom is understood as the place students and teachers interact in the English language lessons. One aspect of the culture is that it can be changed; according to Murphy (1986), in Holliday (1994), cultures are "the products of human activity and thinking and, as such, are people-made" (p. 26). Students changed the classroom culture in terms of types of learning, the roles played by teacher and students, and the classroom routine.

Robinson (1988) and Cheung (2001) stated that two types of knowledge take place inside schools: one is the related to the subject matter and the other is concerned with the world. Regarding learning about the subject matter, English, I found some concepts that helped me explain what happened in the classroom: inventive spelling and learning vocabulary. Inventive spelling occurred when learners listened to a word but did not see it in the written form so pupils made up its spelling. Some examples of this phenomenon were Ti for tea; musicc for music; jalowin for Halloween (Survey, Nov. 13th). Besides that, Lawrence (2001) states that "spelling errors made during the process of writing were not viewed as impediments to learning, but as opportunities for the observant teacher to notice how children were making sense of sound-letter relationships (p. 265). Students also learned vocabulary; Rasputin wrote: "I learned many words in English like homeless, live, mole, etc." (Survey, Nov. 13th).

In relation to learning about the world, one student wrote that he learnt "a mole makes tunnels" (Survey, Nov. 13th). I found that he learnt that information from his classmates because the presentation of this word occurred in this way:

52. T: What Does mole mean? What is a mole?

53. Nerón: What do you write?

54. Boy: An animal.

55. T: and where does it live?

56. Ss: (inaudible) in the land.

(Video transcriptions, Nov. 13th)

In the previous example pupils were sharing their knowledge when one explained to the other what a mole was, and according to McKay and Hornberger (1997, p. 439), classrooms must generate knowledge sharing on the part of the students. Materials had a great influence on students' engagement and interest in the foreign language class. Most of the students wrote their opinions about the materials used in each lesson and showed their curiosity for learning about other worlds. Beto said that "it was funny to see the videos from other countries, because he could see how people lived, their routines, and how they spent their free time" (Survey, Nov. 4th). Beethoven stated: "the materials were good because they were different from other school subject matters" (Survey, Nov. 4th). In the surveys students gave some advice regarding materials that could be useful in class. This confirmed what Nieto (2002) says about students helping to build a better atmosphere in the classroom.

Conclusions

Students read the foreign culture in light of their own reality by using their previous knowledge, making connections between foreign and home issues learned from media, using home culture standards to assess their own reality, acknowledging foreign culture development, and reshaping their beliefs about the foreign culture. When students interacted with something new that did not have any kind of equivalent in their home culture they tended to look for a suitable and familiar referent to make sense of it. This process was influenced by students' previous knowledge and experiences. Some examples: Buckingham Palace with Bogotá, hip-hop with champeta, and tea with coffee.

In the school context analyzed throughout this study, mass media (especially national TV) exerted great influence in the connections that students made between situations lived in Colombia and the content presented in the culture-based materials used in this research. For instance, students had not had any direct contact with a typical sport of the USA (American football, for example) but as they had watched a film where it was played, they made sense of it and gave their opinions about the sport and sportsmen's behaviors. The same happened with some historic situations when they connected our Colombian situation of forced resettlement with the USA invasion of Iraq, and with the formation of Great Britain. The other example occurred when students connected Buckingham Palace with the White House.

Based on the awareness raised through the analysis of the culture-based materials, students took a stand on politics, challenged home culture policies by using the foreign culture as a parameter. Pupils went beyond their usual level of analysis, for example, expressing emphatically what they would do if they were the politicians in our country. By doing so, students reflected upon and analyzed some critical socioeconomic aspects of home culture.

In order to read the foreign culture students expressed their beliefs about it using idiomatic expressions. When students found situations in the foreign culture which caused an impact on them, they chose idiomatic expressions in their mother tongue to effectively communicate that impact. Consequently, language played an important role when sharing beliefs, feelings, and understanding about other cultures.

When students read the foreign culture using their home culture parameters they could not easily accept that reality. It was difficult for them to accept that teenagers of their same age were taller and looked stronger than they did. For this reason they emphasized that American teenagers were older than they were. Besides that, pupils found that they behaved differently from American teenagers in parties; here they are livelier. So, they deduced that American teenagers were bored in their parties.

When students established contact with the foreign culture they reshaped their beliefs about it. Pupils recognized that American institutions were more organized than ours, and that sports were more advanced than ours too. Before coming into contact with culture-based materials, they used to think that in American schools there were not any Afro-Americans. They then noticed the different ethnic groups who live abroad.

Students read their home culture by contrasting their social selves with the foreigners'. They used home culture parameters and described themselves in relation to others. So, pupils evaluated their self-concept, which provoked their thinking about their ideal selves and reshaped their own values like environmental protection, dialogue, tolerance, and coexistence. This comparison led students to value the richness of their home culture too. Some home culture elements were music, famous characters printed on their currency, and landscapes. Likewise, students kept a balance between the foreign and the home cultures. They found commonalities in both positive and negative aspects, things that cultures shared such as their behaviors when watching sports, poor people's occupations, historic situations, and means of transportation.

Pedagogical Implications

It is of much value that people involved in educational matters, particularly in teaching a foreign language, are aware of their own beliefs about the foreign and home cultures. Teachers' practices, voices, feelings, and opinions revealed in classrooms shape students' identities. We are responsible for the kind of ideas generated in our practices; we cannot be far from the role that we assume when being teenagers' educators.

Culture is a construct that must be at the heart of education; students have their own way to interpret the materials used in our practice. Having this in mind, we must be aware of the culture that is being placed on or introduced to them, and of the kind of ideas presented to them.

Culture is broad and we always have to keep it in mind if we want to really help in the transformation of this violent world into one in which everyone respects the other's point of view. Hence, teachers must hear students' voices after the lessons to know what they think, learn, or feel when attending a class where a foreign culture is presented, and also to be familiar with students' readings of different worlds. That is, teachers must guarantee their students' literacy of foreign and home cultures.

Considering that pupils have numerous ways to approach different realities (foreign culture, in this case), it is strongly recommended that educators use a wide diversity of materials to make sure their classrooms are places of learning for everyone. The use of video is strongly suggested due to the great influence that it puts toward students' class engagement, and on their production of multiples responses which ultimately enrich the teaching and learning process. Regarding the nature and the role of materials in students' understanding of home and foreign cultures, resources must motivate students' curiosity to know about different worlds, and the resources need to touch pupils' lives because they could foster students' engagement in foreign language classes and teamwork.

1 These videos were recorded by a teacher who was working for an American school in Virginia and who helped me to collect authentic materials for this study.

2 The expressions in quotation marks correspond to students' Spanish ideas translated into English for the purpose of this publication.

3 Champeta is the cultural phenomenon and musical genre of independent and local origin from the African descendents in the areas in and around Cartagena de Indias, (Colombia). It is also associated with the culture of Palenque of San Basilio. San Basilio is located in Bolívar, in northern Colombia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Champeta

4 The expressions in quotation marks correspond to students' Spanish ideas translated into English for the purpose of this publication.

References

Bell, J. (1999). Doing your research project. Buckingham: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Cambridge University Press (Ed.). (1995). Cambridge international dictionary of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Cárdenas B., M. L. (2000). Producing Materials to Respond to Children's Local Needs. ELT Conference Proceedings, Bogotá. Retrieved from http://www.britishcouncil.org.co/english/english/colenelt.htm [ Links ]

Cheung, C. (2001). The use of popular culture as a stimulus to motivate secondary students' English learning in Hong Kong. ELT Journal, 5(1), 55-61. [ Links ]

Collins, J. (2000). Are you talking to me? The need to respect and develop a pupil's self-image. Educational Research, 42(2), 157-166. [ Links ]

Cortazzi, M., & Jin, L. (1999). Cultural mirrors. Materials and methods in the EFL classroom. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Culture in Second Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 196-219). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Damen, L. (1987). Culture learning: The fifth dimension in the language classroom. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Danielewicz, J. (2001). Teaching selves. Identity, pedagogy and teacher education. New York, NY: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Dolby, N. (2003). Popular culture and democratic practice. Harvard Educational Review, 73(3), 258-277. [ Links ]

Kiesewetter, J. (2003). (Television broadcast, May 30). In R. Dominick (Executive Producer). The Jerry Springer Show. Virginia, USA: Universal Talk Television Productions. [ Links ]

Elsworth, S., Rose, J., & Date, O. (1999). Go for English 1. Turin: Longman. [ Links ]

Elsworth, S., Rose, J., & Date, O. (1999). Go for English 2. Turin: Longman. [ Links ]

Elsworth, S., Rose, J., & Date, O. (1999). Go for English 3. Turin: Longman. [ Links ]

Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy. Reading the word and the world. Westport: Bergin & Garvey. [ Links ]

Halliday, M. (1990). Written and spoken language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Harris, M., Mower, D., & Sikorzynska, A. (2001). Opportunities, pre-intermediate. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Holliday, A. (1994). Appropriate methodology and social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hubbard, R., & Power, B. M. (1999). Living the questions. A guide for teacher researchers. York, Maine: Stenhouse. [ Links ]

Kramsch, C. (1999). Language and cultural identity. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Larsen-Freeman, D. (1991). Second language acquisition research and methodology. In An introduction to second language acquisition research (pp. 10-51). London: Longman. [ Links ]

Lawrence, R. (2001). Invention, convention, and intervention: Invented spelling and the teacher's role. A Journal of the International Reading Association. The Reading Teacher, 55(3), 264-273. [ Links ]

McKay, S., & Hornberger, N. (1997). Sociolinguistics and language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

McKay, S. (2000). Teaching English as an international language: Implications for cultural materials in the classroom. TESOL Journal, 9(4), 7-11. [ Links ]

McLaren, P. (2003). Life in schools: An introduction of critical pedagogy in the foundations of education (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publications. [ Links ]

Miller, R., Fernández, V., & Price, K. (1999). The 50 States. New York, NY: Tangerine Press. [ Links ]

Nieto, S. (2002). Language, culture, and teaching: Critical perspectives for a new century. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Oxford University Press. (Ed.). (1993). Oxford advanced learner's dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Robinson, G. (1988). Cross cultural understanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Roth,W. M., & Harama, H. (2000). (Standard) English as second language: Tribulations of self. Journal Curriculum Studies, 32(6), 757-775. [ Links ]

Soars, J., & Soars L. (1993). Headway-Elementary. Sudents' book. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Soars, J., & Soars L. (1993). Headway Video-Elementary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Storey, J. (1996). Cultural Studies and the study of popular culture: Theories and methods. Athens: The University of Georgia Press. [ Links ]

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research grounded theory procedures and techniques. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Tomalin, B., & Stempleski, S. (1994). Cultural awareness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Tomlinson, B. (1998). Materials development in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Tudor, I. (2001). The dynamics of the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

About the Author

Mireya Esther Castañeda Usaquén holds a BEd in Philology and Language-English (Universidad Nacional de Colombia) and a Masters in Applied Linguistics to TEFL (Universidad Distrital, Colombia). She also studied in a professional development program at Universidad Nacional de Colombia. She has worked in primary and high schools, and in universities. She currently works for Secretaría de Educación de Bogotá and Universidad Antonio Nariño, Bogotá, Colombia.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Esperanza Vera who was my mentor during the Master's Program and to Judith Astrid Rodríguez who was teaching Spanish in the USA and collected authentic materials for this study.

![]()