Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

versión impresa ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.16 no.1 Bogotá ene./jun. 2014

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.38661

http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n1.38661

Selective Use of the Mother Tongue to Enhance Students' English Learning Processes...Beyond the Same Assumptions

Uso selectivo de la lengua materna para mejorar el proceso de aprendizaje del inglés de los estudiantes...Más allá de las mismas suposiciones

Luis Fernando Cuartas Alvarez

Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia

luisfdocuartas@gmail.com

This article was received on July 1, 2013, and accepted on November 5, 2013.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Cuartas Alvarez, L. F. (2014). Selective use of the mother tongue to enhance students' English learning processes...beyond the same assumptions. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 16(1), 137-151.

This article reports the results of an action-research project that examines enhancing students' English learning processes through the selective use of their mother tongues with the aim of overcoming their reluctant attitudes toward learning English in the classroom. This study involves forty ninth-graders from an all-girls public school in Medellin, Colombia. The data gathered included field notes, questionnaires, and participants' focus group interviews. The findings show that the mother tongue plays an important role in students' English learning processes by fostering students' affective, motivational, cognitive, and attitudinal aspects. Thus, the mother tongue serves as the foothold for further advances in learning English when used selectively.

Key words: English as a foreign language, language learning, mother tongue, selective use of mother tongue.

Este artículo presenta los resultados de un proyecto de investigación-acción que examinó el mejoramiento del proceso de aprendizaje de inglés de los estudiantes, a través de un uso selectivo de la lengua materna con el objetivo de superar la actitud reacia hacia el uso del inglés dentro del aula de clase. En este estudio participaron cuarenta estudiantes de noveno grado de un colegio público femenino de la ciudad de Medellín, Colombia. Los datos recogidos incluyen notas de campo, cuestionarios y entrevistas de los participantes a través de grupos focales. Los resultados muestran que la lengua materna juega un papel importante en el proceso de aprendizaje del inglés, al fomentar aspectos afectivos, motivacionales, cognitivos y actitudinales. Así, la lengua materna se sitúa como el punto de apoyo para seguir avanzando en el aprendizaje de inglés, cuando se utiliza de manera selectiva.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje de lenguas, inglés como lengua extranjera, lengua materna, uso selectivo de la lengua materna.

Introduction

Mainstream language teaching methodologies uphold the English-only practice at schools. This teaching style assumes that English ought to be learned solely through English (henceforth, L2) and not with the help of mother tongue (henceforth, L1), which in fact tend to be prohibited in the classroom (Jadallah & Hasan, 2010). Nevertheless, practices in schools vary considerably. The mother tongue, especially at public institutions, occupies a large proportion of the language used in class. Both students as well as teachers constantly resort to L1, leading to its overuse and to avoiding using English.

The aforementioned scenario was not an exception in the institution where this study took place, an all-girls public high school located on the northwest side of Medellin with approximately 2,200 students from low and middle-low socioeconomic status. At this school, one of the most recurrent issues was that students, particularly ninth-graders, overused L1 in the classroom and showed negative attitudes toward using English. I shared my concern with my cooperating teacher (CT), who mentioned that this group had had very poor experiences with English because their previous teachers had conducted all classes in Spanish and the students were always being asked to translate texts (Informal conversation with CT, February 23, 2012). Despite the efforts of my CT to encourage English use in class, the students remained reluctant and resorted to L1 instead. Eventually, my CT resorted to using L1 to teach his class instead.

At this time, I questioned myself about the possible reasons for this issue. I wondered whether the teacher, the lessons, the topics, the language, or the classroom environment were influencing the students' constant dependence on L1. As my observations continued, I noticed that the students were unmotivated to use English and that they would use L1 all of the time. As a countermeasure for their constant dependence on L1, my CT insisted on asking students to perform oral tests, quizzes, and short presentations as a way to force them to use English in class. However, students preferred to receive bad grades than to share their work in class. The students' frustration was evident as the classes went on: "Teacher, I don't understand anything"; "Teacher, it's just that I'm stupid"; "Teacher, don't worry about me because I'm not going to study anymore" (Class Journal, February 23 and March 1, 2012).1 I decided to push this issue further by talking with those students, and I realized that most of them actually did their homework, but their lack of confidence in using English prevented them from presenting their homework in class.

This situation reflected a serious issue-when students' confidence levels and grades drop, they "may very well experience an unnecessary sense of failure" (Jones, 2010, p. 16), a very distant sense from what we may expect from a class. I understood that a methodological renewal was required to overcome this sense of failure and to inculcate in the students a sense of success that could be represented by an increase in English use within the classroom. I stated this in my journal: "To bring them [students] a sense of success would improve students' morale. This could result in better development of the activities and, eventually, better outcomes from them" (Class Journal, March 1, 2012).

Based on these data, I decided to take a different pathway by searching for information related to the use of L1 in the classroom. Beyond the taken-for-granted assumptions regarding its use, I found that the selective use of L1 could actually be beneficial for L2 learning. I also found that the problem stems not from the use of L1 but from the way in which it is used in the classroom. L1 can be actually used alongside English without displacing it as the main medium of communication (Butzkamm, 2003). It can be used as a support for students to express themselves and be understood by others even when their proficiency in English is not adequate (Cook, 2001). Additionally, L1 can be used to provide students with scaffolding to communicate in a non-threatening environment (Antón & DiCamilla, 1998; Auerbach, 1993), increasing confidence, reducing reluctance, and enhancing English learning.

However, when advocating for the use of L1, it is important to remark on the fact that there is no guideline regarding its appropriate use. In addition, there is no criterion that establishes either specific dosages or purposes for which L1 should be used to enhance L2 learning. Thus, finding a balance of L1 use appears to be a matter of reflection, judgment, and selectivity. "L1 can be a valuable resource if it is used at appropriate times and in appropriate ways" (Atkinson as cited in Cole, 1998, "L1 and Communicative Language," para. 8). This last is what best represents a selective use of L1: using L2 when possible and L1 when necessary and positioning L1 as a conscious and meditated choice with a facilitative and supportive role for students (Jadallah & Hasan, 2010).

Considering all of the findings acknowledged here, this research project sought to enhance students' English learning process through the selective use of L1, increasing both confidence and English use and fostering a non-threatening environment for language learning. Therefore, to frame this research inquiry, I proposed the following research question: How can the selective use of L1 enhance a group of ninth-graders' English learning processes in the English as a foreign language (EFL) classroom at a public school in Medellin?

Theoretical Framework

The following theoretical framework presents the arguments, assumptions, and concepts that will support the aim of this study. First, I portray a brief analysis of the debate around the use of L1 in the EFL classroom. Second, I present a brief state of the art of the research conducted on this issue and how the findings support the benefits of using L1. Third, I show some possibilities of L1 use in the EFL classroom. Fourth, I provide reasons that monolingual approaches to language teaching should be reconsidered in our country. Ultimately, I propose reasons L1 use could be beneficial in the Colombian EFL context.

The Debate Around the Use of L1 in the EFL Classroom

The use of L1 in the EFL classroom has been a polemic issue and the subject of much controversy and debate for decades. On the one hand, supporters of monolingualism in EFL, for instance, advocate that L2 should be used solely and exclusively within the classroom as the teaching and learning medium, avoiding the use of L1, which would reduce the amount of input provided to students in the target language (Polio & Duff, 1994). This assumption portrays a scenario in which L2 is appropriate, suitable, advisable, and the norm, and L1 is the opposite, detrimental, taboo, and the "skeleton in the cupboard" (Prodromou as cited in Butzkamm, 2003, p. 29); this scenario, implicitly or explicitly, reinforces the assumption that English is the only acceptable way to communicate in the EFL classroom (Auerbach, 1993). On the other hand, other authors have dissented from this assumption (Atkinson, 1987; Butzkamm, 2003; Cook, 2001). Cook (2001), for instance, mentions that the avoidance of L1 in the EFL classroom has been undoubtedly justified for decades. Nonetheless, there have been moments in history when this commonsense assumption has been rejected. These authors are progressively defying the English-only assumption (Auerbach, 1993), calling into question its suitability for EFL teaching and learning, particularly in non-English-speaking countries, and the role that L1 plays within EFL learning.

Beyond the Same Assumptions

This new stance toward the role of L1 has resulted in an increasing repertoire of relevant research studies supporting the benefits of using L1 from different sociolinguistic contexts that not only provide insights into the favorable attitudes from both teachers and students toward L1 use but also support the premise that L1 can actually facilitate L2 learning. Schweers (1999) conducted a study at a Puerto Rican university with 19 teachers and their students in an EFL context. The aim was to investigate the teachers' and students' attitudes toward using Spanish in the L2 classroom. The results showed that using Spanish led to positive attitudes toward the process of learning English and better yet, encouraged students to learn more English. Tang (2002) conducted a similar study in China with 20 teachers and 100 students. The aim was to investigate their attitudes toward using Chinese in the L2 classroom. The findings showed that limited and judicious use of the mother tongue in the classroom did not reduce students' exposure to English but rather, could assist in the teaching and learning processes. Miles (2004) utilized three low-level first-year university classes of Japanese students to find evidence of the theory that L1 use can facilitate L2 learning. The results supported that L1 use in the English classroom did not hinder L2 learning but rather facilitated it. Drosatou (2009) involved six Greek English language teachers as well as 30 students in her study. The study's aim was to analyze to what extent Greek was used in the L2 classroom. The results showed that teachers were likely to use L1 in the classroom and that students were mostly in favor of using both languages in class.

Uses of L1 in the EFL Classroom

Some authors have provided for some uses for the L1 in the EFL classroom (Atkinson, 1987; Cook, 2001). Atkinson (1987), for instance, describes favorable uses such as eliciting language, checking comprehension, giving instructions, encouraging cooperation among learners, discussing classroom methodology, presenting and reinforcing the language, checking for sense, and testing and developing useful strategies. In addition, the use of L1 facilitates the incorporation of students' life experiences and their knowledge of the world (Auerbach, 1993; Miles, 2004). These experiences are the starting points for comprehension and the references for students to connect what they have lived and learned with the L2. In addition, L1 use provides students with an effective tool for cross-linguistic analysis, confronting the new language with their already-existing mother tongue (Butzkamm, 2003). Additionally, L1 use improves the students' affective filters and the EFL learning environment; its use facilitates an affective environment for learning and reduces students' anxiety levels and other affective barriers (Auerbach, 1993; Jones, 2010). Students who are unmotivated, without self-confidence, or anxious are less likely to utilize L2 in the classroom. By using L1, they could reduce their inhibitions or affective blocks, which would encourage them to use English in class in more confident ways than would otherwise be possible in a solely EFL environment. Finally, although the discussion about L1 use in the L2 classroom has not passed unnoticed by researchers and practitioners in our country, there are scarce studies in Colombia regarding whether L1 should be used in EFL classrooms.

Reconsidering Foreign Language Teaching in the Colombian EFL Context

Foreign language teaching in Colombia relies on imported models that emphasize conformity to standards and norms of an idealized native English speaker as the main objective of language competence (Velez-Rendón, 2003). These imported monolingual models, however, fail in the Colombian context and its specific features because of several factors.

To begin with, these models are forged in Anglo sociolinguistic milieus, in which the implications of different languages apart from English are not considered. Additionally, these models are implicitly elitist and they predominantly favor high socioeconomic sectors and marginalize low socioeconomic ones, which reinforces the ever-increasing division between private and public education in Colombia (Velez-Rendón, 2003). Moreover, the curricular experiences from these models could be pedagogically justified except that they rely on unfounded assumptions that have not been fully examined, and their inner discourses encompass relationships of power and maintenance of the status quo (Auerbach, 1993; Freire & Macedo, 1987). Furthermore, monolingual models and English-only policies overlook the current conditions of teachers in the public sector. The teachers are asked to preserve the English-only policies in their classes, but they also must acknowledge the scarce opportunities for maintaining English use in the classroom and the lack of in-service training and professional development programs available to them (Gonzales as cited in Velez-Rendón, 2003). Finally, these models have been applied without considering the constant challenges that come with the lower socioeconomic conditions of our country, such as "non-motivated students, lack of support and resources, overcrowded classrooms, lack of adequate space and quality materials, and lack of morale" (Gonzales et al. as cited in Velez-Rendón, 2003, p. 192).

Positive Effects of L1 in the Colombian EFL Context

In a context in which English is learned as a foreign language, applying monolingualism then represents adopting the pretension of abolishing L1 from the EFL classroom, which deprives students of a fundamental tool for reflection, critical thinking, and social interaction (Freire & Macedo, 1987). Moreover, this represents excluding the students' most intense existential experiences obtained through their L1 (Phillipson as cited in Auerbach, 1993). In addition, this represents a lack of acknowledgement of the fact that students "have learnt to think, learnt to communicate and acquired an intuitive understanding of grammar" through their L1 (Butzkamm, 2003, p. 31).

However, by acknowledging and welcoming the use of L1 within the EFL classroom, negative attitudes toward English could be dispelled and receptivity to learning the language could be increased (Schweers, 1999). In addition, L1 use could present linguistic, cognitive, affective, political, psychological, and social benefits, which would favor both students and teachers (Jones, 2010). All of the possibilities above call for a reconsideration of L1 use in the English classroom as a possible teaching and learning resource that may be beneficial not only in the Colombian EFL context but also in other EFL contexts in different Spanish-speaking countries.

Method

Planning Actions

To enhance students' English learning through the selective use of L1, I planned to perform the following actions: (a) inform students about the aims of the study as well as the implementations to be performed in the English classes, (b) modify the teacher's speech in the English classes, (c) permit students to resort to their L1 but guided by established boundaries, (d) promote collaborative work among the students during the classes, and (e) modify the class methodology towards a more communicative approach.

Additionally, to collect qualitative and quantitative data for this study, I planned to use the following instruments: (a) field notes from all of the classes observed and taught during the school year to record the events within the classroom; (b) two questionnaires in Spanish, the first adapted from Schweers (1999) and Tang (2002) and including closed-ended questions to analyze the students' perceptions toward English and L1 use, and the second, also including closed-ended questions and a section for reflections, to analyze the impact of the implementations performed in class; (c) audio-recording of two structured interviews with my CT to collect insights about the class, the students, and their use of language (L1 and L2); and (d) audio-recording of three semi-structured focus group interviews with five students each to gain insights on their perspectives toward L1 use and the implementations performed in class. In the following section, I provide more details of each teaching action and its development.

Development of the Actions

The aforementioned actions were developed throughout the second semester of this study and were aimed at fulfilling the study objective. First, I informed students of the purpose of this study as well as what was going to be implemented in the class. I described that my objective was to enhance the students' English learning processes through the selective use of L1. However, I clarified that using L1 as a tool did not mean the whole class would be in Spanish. I emphasized that English use was going to be increased in the classroom because the main objective of an English course is for the students to actually learn English. By sharing the implications of the study, I expected students to dispel any prior ideas regarding the constant use of L1 in class and to progressively invite them to use it consciously and purposely.

Second, I modified my teacher's speech by maintaining a clear tone of voice and slow but careful pronunciation. In addition, I modified the way instructions were given in class; they remained in L2 but were continuously simplified to match them to the students' English levels (e.g., avoiding idiomatic expressions, difficult tenses and vocabulary). Additionally, I utilized code switching between L1 and L2 on certain occasions to emphasize important concepts, to reacquire the students' attention, and to supply difficult vocabulary items, as suggested by Cook (2001). By making such modifications, I expected to facilitate a progressive increase in the input provided in L2 during classes, an idea that is supported by Butzkamm (2003), who states that "when used properly, the L1 steals very little time away from the FL [L2] and, in fact, helps to establish it [L2] as the general means of communication in the classroom" (p. 32).

Third, I permitted students to resort to L1 during the classes, under established boundaries, as a way to express themselves, to convey language, and to make inner connections between their own knowledge and experiences and the topics in English. Additionally, I permitted the use of L1 in class as a way to provide students with a supportive tool to help them organize their ideas and, therefore, express themselves in L2. By allowing students to use L1, I expected them to increase their confidence and to realize that they were actually able to respond successfully, increasing their participation in class. This action was based on the premise that the more English knowledge the students acquired, the less dependent on the mother tongue they would be.

Fourth, I promoted collaborative work among the students, facilitated by the use of L1 as a way to incorporate their own life experiences and knowledge, to create a non-threatening environment in which to work and to allow students to give each other feedback to increase their confidence and learning (Antón & DiCamilla, 1998; Auerbach, 1993). By promoting this kind of work, I expected students to find support from their peers to overcome their difficulties together in a free and motivating environment that would improve their performance in class.

Finally, I modified the class methodology toward a more communicative language teaching approach instead of the prevalent grammar-translation tendency. This tendency, based mainly on translation exercises, had permeated the students to such a degree that they had to perform translations before trying any exercises in English, as presented in the following excerpt from a reflection students had to deliver as homework:

Reflexión del cigarrillo y el alcohol

El alcohol como el cigarrillo son muy malos el alcohol te destruye tus pulmones te da mal aliento te causa infarto aborto y miles de cosas que perjudican tu salud al igual que el alcohol te daña el cerebro te daña la dentadura y daña tu aspecto. Pero así nosotros somos muy tercos por que los seguimos consumiendo pero lo peor de todo que estos dos productos son adictivos y dañan tu vida.

Reflection of cigarette and alcohol

Alcohol and cigarettes are very bad alcohol destroys your lungs you gives you bad breath cause abortion infarction and thousands of things that harm your health like alcohol damages the brain you will damage the teeth and damages your appearance. But we are very stubborn and that we continue to consume but the worst of all that these two products are addictive and damaging your life. (Homework collected from student, September 25, 2012)

Instead of maintaining this tendency, I applied communicative tasks that encouraged students to use English such as role-playing, presentations, games, and dramatizations among others. These communicative tasks were facilitated by the use of L1 supported by Cole (1998), who acknowledges the role that L1 plays within this approach.

In addition, I decided to incorporate more meaningful, context-related and authentic topics (e.g., moral dilemmas, pregnancy, and drug consumption) as a way to increase students' motivation and to allow further discussions. By making these modifications, I expected students not only to realize the importance of L2 as a medium of communication but also to relate their learning to life situations, making learning meaningful even outside of class.

Data Analysis

To analyze the data collected, I followed the framework for qualitative data analysis proposed by Burns (1999) involving assembling, coding and comparing the data, building interpretations, and reporting the outcomes.

First, to analyze the field notes, I systematically read the different journal entries written after each class. Afterward, following Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw (1995), I coded the data by using open and focused coding to look for emerging patterns. I then established some preliminary categories for arranging the data. Once I finished this, I reread the field notes to code the arranged data into the identified broader categories.

Second, to analyze the questionnaires, I first gathered the responses into a chart I arranged. Afterward, I tabulated the number of responses for each item and set them into percentages. Then, following the recommendations of Bell (1993), I coded and recorded the responses as soon as they were tabulated and arranged. Once I was finished, I created a visual display by putting the data into graphic charts.

Third, to analyze the CT and focus group interviews, I first transcribed the entire interviews for subsequent analysis. Afterward, I coded the interviews' transcripts through open and focused coding to identify emerging ideas, patterns, and issues. Finally, I arranged the codes into preliminary and broader categories.

At the end, the entire process was validated by triangulation of the different data sources with the aim of enhancing the trustworthiness of my findings and by peer examination to determine my advisor's opinions regarding my findings, which were acknowledged as logical and reasonable. This process helped me to build interpretations and articulate them with my research question and objectives. In the following section, I provide a summary of what I found.

Findings and Interpretations

The findings of this study, the purpose of which was to enhance the students' English learning processes through the selective use of L1, were encompassed in terms of (a) the students' use of L1 and (b) the teachers' use of L1, all of these comprising the role that L1 plays in enhancing students' English learning processes. In the following sections, I provide further explanations of each of these findings.

Students' Use of L1 Enhancing Their English Learning Processes

The data revealed how the students' use of L1 enhanced their English learning processes in specific aspects such as acquiring and defining vocabulary, which led to English learning and increasing confidence (see Appendices A and B). Below, I provide further details regarding these uses.

Acquiring and Defining Vocabulary in English

Data from this study revealed that L1 played an important role in the EFL classroom by helping students to understand and acquire vocabulary in English, as illustrated in the following excerpt from a focus group in which one student expressed how her L1 use helped her in learning English vocabulary:2

[The use of Spanish] has helped me a lot at the moment of learning more vocabulary in English, because when I am taught new words and I don't have a clear meaning in Spanish, I forget them, but when I can and am able to connect them with their meaning, it is easier to learn them and retain them. (Focus Group, November 17, 2012)

The excerpt above shows how the L1 use assisted students in learning vocabulary by providing an effective tool for cross-linguistic analysis to confront both English and Spanish because "every new language is confronted by an already-existing mother tongue" (Butzkamm, 2003, p. 30). This tool allowed students to analyze and compare words in English to make connections with their counterparts in L1, thus facilitating acquisition and retention. In addition, the use of L1 as a cross-linguistic tool was important for students' learning; they acknowledged its usefulness as a way to elicit meaning from the English vocabulary, as illustrated in the following excerpt from a focus group: "For me, Spanish is really important for learning English because it's as I say, for me is a comparison, I compare a word in English with one in Spanish to be able to understand it" (Focus Group, September 13, 2012). This process of comparison is worth consideration because "students are, especially at lower levels, always using their knowledge of the world and their L1 to make comparisons with English . . . trying to make it [L2] more comprehensible" (Ferrer, 2002, p. 4).

Leading to English Learning

The data showed that L1 use also played a sup-portive and facilitative role within the EFL classroom by leading the students through the process of learning the foreign language. Students utilized their L1 as a reference point to compare grammar structures and to make sense of the information that had been provided in the L2, as illustrated in the following excerpt from a focus group:

The use of Spanish does help me at the moment of learning more English because it seems easier to learn and retain the information when I make some kind of comparison between these two languages, for example in the structure of a sentence. Although it is different in each language, Spanish helps me to identify the parts of the sentence such as the verb, subject, complement, etc., and, with this as a base, to be able to easily learn and identify the parts or structures of one sentence in English. (Focus Group, November 17, 2012)

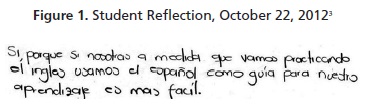

Thus, L1 appeared to be a tool for learning the foreign language, which helped students to achieve a better understanding of the mechanics of English by making comparisons and creating signposts to associate similar structures in both languages. This role of L1 in facilitating students' access to English was acknowledged by Butzkamm (2003), who stated that L1 "is the greatest asset people bring to the task of foreign language learning . . . the tool which gives us the fastest, surest, most precise, and most complete means of accessing a foreign language" (p. 31). This role of L1 was also intuitively acknowledged by the students, who understood that their mother tongue was their foothold to advancing in L2, which facilitated their understanding and served as a guide in learning L2, as illustrated in Figure 1, which shows an excerpt from a student's reflection regarding whether the L1 use had helped her enhance her learning process.

Increasing Confidence in the Classroom

The data revealed that the L1 use played an important role in increasing students' confidence in utilizing the L2 within the EFL classroom. In fact, students were allowed to moderately resort to L1 in some activities as a way to overcome nervousness or any other difficulties that could have appeared when they were expressing their ideas in L2. For instance, during an activity in which students had to describe some words to their classmates, I allowed them to resort to L1 with established boundaries such as only a specific number of words in L1, as illustrated in the following excerpt from my journal in which I asked one student to describe a specific word as part of a game in class:

I gave the word corn and she was confused; she knew neither the meaning of the word nor how to explain it in English. She asked me if I could allow her to use Spanish to explain the word. I told the class that I was going to allow them to use Spanish but just for three words. (Class Journal, September 10, 2012)

This selective use of L1 increased students' confidence to face the challenge of using L2 during class activities and increased their satisfaction after performing those activities, as is illustrated in the following excerpt from a focus group: "[The use of Spanish] gave me confidence. For example, when we have to go in front to explain something [in English] and because we could talk in Spanish, we could do it a little better, and by doing so, we felt better" (Focus Group, November 17, 2012).

Consequently, using L1 during class activities increased students' motivation toward and interest in the subject, which was reflected in their improved performance, participation, and attitudes toward learning English, as evidenced in the following excerpt from a focus group: "[The use of Spanish] helped me in many ways. For example, I paid more attention in class, I was more encouraged to participate in class and I buckled down to do the tasks in class" (Focus Group, November 17, 2012).

Teacher's Use of L1 to Enhance Students' English Learning Processes

The data revealed that the teacher's selective use of L1 served to enhance the students' English learning processes in specific aspects such as helping them to comprehend vocabulary, clarifying doubts when giving explanations, and providing affective support in the English classroom (see Appendices A and B).

Helping Students Comprehend English Vocabulary

The data showed that the teacher's selective use of L1 helped students to comprehend vocabulary in English. Then, using L1 selectively to elicit meaning and providing accurate translations to L1 when necessary assisted students in comprehending and learning the L2 vocabulary, as illustrated in the following excerpt from my journal in which a student constructed her own statements to describe some words to her classmates as part of a class activity:

Another student came, and this time the word was submarine. She asked me how she could say bajo el agua, I quickly replied "underwater," and then she started saying, "is something underwater...with periscopio" [periscope]. Students immediately understood it was a submarine. (Class Journal, September 10, 2012)

Additionally, by providing accurate and selective translations when necessary, teachers can help students construct language. To illustrate this, in one class, one student had difficulties understanding a question about her age because she was not accustomed to being asked orally in English. By using L1 selectively, however, I could help her to make connections with her prior knowledge to respond adequately, as evidenced in the following excerpt from my journal:

I carefully said just one word in Spanish after saying the question; this automatically re-focused the student and created the connection between the question itself and her prior knowledge, allowing her to answer correctly. For instance, how old are you?...edad [age]...then she answered "I'm fifteen years old." (Class Journal, July 23, 2012)

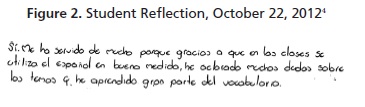

This selective use of L1 is especially useful when working with young or low-proficiency students, such as the ones in this study, who may find it difficult to understand and remember the meanings of certain words, helping them create a clear picture of those words and foster their learning. In fact, in a reflection, a student mentioned what is shown in Figure 2 when asked about how the L1 use had helped her learn English.

Nonetheless, as part of using L1 selectively, other options such as body language, exemplifications or realia should also be considered and not dismissed out of hand. These options were used throughout the classes as aids for students to understand what was provided in L2 and to avoid constantly resorting to L1, as illustrated in the following excerpt from my journal:

When students were unable to understand the question, I tried different alternatives (aids) to make them understand: I tried using gestures like using my hand as a telephone to make them tell me their telephone number; also I tried to make examples by answering the questions and then asking again to see if they [students] got it, for example "I'm 24 years old, how old are you?" Also I tried to point out what the question was about, for example "What is your favorite TV program?" (pointing to the TV in the classroom). (Class Journal, July 23, 2012)

Although these options were used with the purpose of eliciting students' language through questions, they can also be associated with other purposes such as asking students for meaning and providing them with new and more complex vocabulary, just to mention a few.

In general, the findings above are in accordance with those of other authors who have also found favorable responses toward L1 use in terms of explaining vocabulary and difficult concepts for general comprehension (Cianflone, 2009; Jadallah & Hassan, 2010; Schweers, 1999; Tang, 2002).

Clarifying Doubts When Giving Explanations in English

The data revealed that the teacher's selective use of L1 played an important role in clarifying and resolving students' doubts when giving explanations, as illustrated in the following excerpt from a focus group:

The use of Spanish helped me a lot because I believe that in the grade in which I am, I didn't understand when the teacher spoke everything in English; but when he explained to me in Spanish, the learning was more because it helped me to better develop the tasks and homework, and my understanding was better than when he spoke in English. (Focus Group, November 17, 2012)

As a result, L1 adopted a positive role as a facilitator and clarifier that proved to be helpful for students to develop better understanding of the teacher's explanations in L2, which might have sometimes been inaccurate, complex, or unreachable for the students given their levels. This positive role of L1, therefore, permitted students to overcome difficulties when understanding the class activities and tasks, as well as what they were being asked to do, as illustrated in the following excerpt from a focus group:

Spanish helped me in the English class, for example, for some explanations of difficult tasks and in some difficulties that one may have, for example, to know what to do in the tasks, that's one difficulty I present in English [class]...and in that Spanish helped me. (Focus Group, November 17, 2012)

In addition, students felt that they could easily clarify L2 when the teacher used L1 to make meaningful connections between both English and L1, which contributed to their success in understanding and clarifying English explanations, as illustrated the following excerpt from a focus group:

We understand easily in ways that we have been already taught, so, if we have as the main language Spanish, when he [teacher] uses it in class it help us to understand easily, and so when he speaks Spanish, we have more clarity of a topic, an explanation . . . that's why is good that he uses Spanish. (Focus Group, September 5, 2012)

The data also showed how the L1 use served as a direct way to facilitate students' understanding by providing them with precise and effective explanations that would not have otherwise been fully understood by using L2 only. Thus, the use of L1 can be seen as a matter of efficiency, whereby something can be done more efficiently through the L1 (Cook, 2001). For instance, during a class in which the main topic was raising awareness on teen pregnancy, I provided selective explanations using L1 when necessary to facilitate students' understanding and to avoid raising doubts, as illustrated in the following excerpt from my journal:

I asked them [students] to make a list of the things they usually like to do . . . Then I asked them which of those things they would be able to do if they were pregnant. Because the question would have been difficult to express in English, I decided to do it in Spanish for them to understand what I meant. (Class Journal, August 27, 2012)

Providing Affective Support Within the EFL Classroom

The data showed that the teacher's selective use of L1 played an important role in providing students with affective support during classes. In this study, this support came from the accompanying, scaffolding, and caring from the teacher, who adopted a participative role within the classes that is exemplified in the following excerpt from my journal:

After some minutes, I asked the students to start doing the presentations. They were nervous and worried. The students told me: "profe es que no sabemos pronunciar bien, y hay que decir mucha cosa."5 I told them that I was going to be there in front helping them with the presentation and with their pronunciation. This motivated students and enhanced their confidence to carry out the presentation. (Class Journal, September 10, 2012)

This participative role along with a selective use of L1 to support students when constructing language, especially the low-proficiency students, contributed to overcoming the "sense of failure" (Jones, 2010, p. 16) that prevented them from expressing and freely utilizing English in the EFL classroom. In addition, this participative role favored students' performance in class by creating a non-threatening environment for English learning (Antón & DiCamilla, 1998), encouraging them to take risks when participating in class and thereby increasing their confidence and self-esteem.

Conclusions and Teaching Implications

With this study, I was able to determine how the selective use of L1 could favor students' English learning processes as a way to contribute to the ongoing corpus of research knowledge regarding L1 use in the English classroom (Antón & DiCamilla, 1998; Atkinson, 1987; Auerbach, 1993; Butzkamm, 2003; Cianflone, 2009; Cook, 2001; Ferrer, 2002; Jadallah & Hassan, 2010; Schweers, 1999; Tang, 2002). Based on the findings I obtained, it was possible to conclude that the selective use of L1 succeeded in enhancing students' English learning processes within the particular EFL context in which this study took place, as well as in improving students' class performance, their levels of confidence, their language use, the classroom environment, and the students' attitudes toward learning English. At the end, this study contributed to providing a rationale for the relationship between the use of L1 and the students' English learning processes, and it placed L1 as a foothold for further advances in learning English when used selectively. Given this, it is necessary to raise awareness and motivate teachers to inquire about the different roles that L1 may play in the EFL classroom and what role L1 is actually playing within their own classes. This inquiry would not only provide sound bases for teachers to decide on L1 use in their own class contexts but would also favor further reflections on their own practices.

1 These excerpts have been translated from Spanish.

2 All of the excerpts from the focus groups were translated from Spanish.

3 Yes, because to the extent that we are practicing English, we use Spanish as a guide for our learning; it's easier.

4 Yes, it has been useful a lot because thanks to the fact that we use Spanish in the classes to an appropriate extent, I've clarified many doubts about the topics and I've learned most of the vocabulary.

5 Teacher, we don't know how to pronounce well, and there is a lot to say.

6 Thirty-six out of 40 were returned.

7 Thirty-eight out of 40 were returned.

References

Antón, M., & DiCamilla, F. J. (1998). Socio-cognitive functions of L1 collaborative interaction in the L2 classroom. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 54(3), 314-353. [ Links ]

Atkinson, D. (1987). The mother tongue in the classroom: A neglected resource? ELT Journal, 41(4), 214-247. [ Links ]

Auerbach, E. (1993). Reexamining English only in the ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 27(1), 9-32. [ Links ]

Bell, J. (1993). Doing your research project. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Butzkamm, W. (2003). We only learn language once. The role of the mother tongue in FL classrooms: Death of a dogma. Language Learning Journal, 28, 29-39. [ Links ]

Cianflone, E. (2009). L1 use in English courses at university level. ESP World, 8(22), 1-6. [ Links ]

Cole, S. (1998). The use of L1 in communicative English classrooms. The Language Teacher, 22(12). Retrieved from http://jalt-publications.org/old_tlt/files/98/dec/cole.html [ Links ]

Cook, V. (2001). Using the first language in the classroom. Canadian Modern Language Review, 57(3), 402-423. [ Links ]

Drosatou, V. (2009). The use of the mother tongue in English language classes for young learners in Greece (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Essex, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

Emerson, R., Fretz, R., & Shaw, L. (1995). Writing ethnographic field-notes. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Ferrer, V. (2002). The mother tongue in the classroom: Cross-linguistic comparisons, noticing and explicit knowledge. Retrieved from http://www.teachenglishworldwide.com/Articles/Ferrer_mother%20tongue%20in%20the%20classroom.pdf [ Links ]

Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the word and the world. South Hadley, MA: Bergin & Garvey. [ Links ]

Jadallah, M., & Hassan, F. (2010). A review of some new trends in using L1 in the EFL classroom. Retrieved from http://www.qou.edu/english/conferences/firstNationalConference/pdfFiles/drMufeed.pdf [ Links ]

Jones, H. (2010). First language communication in the second language classroom: A valuable or damaging resource? (Master's thesis). Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada. Retrieved from http://nativelanguageuse.weebly.com/uploads/4/0/4/5/4045990/roleofnativelanguage.pdf [ Links ]

Miles, R. (2004). Evaluating the use of L1 in the English language classroom (Master's thesis). University of Birmingham, United Kingdom. Retrieved from http://www.bhamlive3.bham.ac.uk/Documents/college-artslaw/cels/essays/matefltesldissertations/Milesdiss.pdf [ Links ]

Polio, C. G., & Duff, P. A. (1994). Teachers' language use in university foreign language classroom: A qualitative analysis of English and target language alternation. Modern Language Journal, 78(3), 313-326. [ Links ]

Schweers, W. (1999). Using L1 in the L2 classroom. English Teaching Forum, 37(2), 6-9. [ Links ]

Tang, J. (2002). Using L1 in the English classroom. English Teaching Forum, 40(1), 36-42. [ Links ]

Velez-Rendón, G. (2003). English in Colombia: A sociolinguistic profile. World Englishes, 22(2), 185-198. [ Links ]

About the Author

Luis Fernando Cuartas Alvarez holds a B.Ed. degree in Foreign Language Teaching (English and French) from Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia. His research interests are teaching English as a second language and language acquisition. He currently works as a full-time English teacher.

Acknowledgements

To make this study a success, I counted on the participation of a group of persons that I would like to thank: my family and girlfriend, my students, the school staff, my advisors Dr. Ana Maria Sierra and Camilo Andrés Dominguez, my cooperating teacher Robinson Durango and my fellows who contributed to my personal and professional growth as well as to the fulfillment of this study.

Appendix A: Responses to the First Questionnaire6

Appendix B: Responses to the Second Questionnaire7