Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

versão impressa ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.17 no.2 Bogotá jul./dez. 2015

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.48091

http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.48091

Teacher Activities and Adolescent Students' Participation in a Colombian EFL Classroom

Actividades de enseñanza y participación de estudiantes adolescentes en una clase de enseñanza de inglés como lengua extranjera en Colombia

Jefferson Caicedo*

Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia

*jefferson.caicedo@correounivalle.edu.co

This article was received on December 30, 2014, and accepted on March 17, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Caicedo, J. (2015). Teacher activities and adolescent students' participation in a Colombian EFL classroom. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 17(2), 149-163. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.48091.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The present study concerns the activities teachers develop and ninth-graders' participation in responses to those activities. The objectives of this study were to identify and describe the types of teaching activities developed and how students respond to them and to show how the target language is used in the classroom. The data collection was conducted through daily field notes and a diary. The findings show that in the classroom, the teacher develops twelve types of activities, and the percentage of use of the target language is low.

Key words: Class activities, foreign language, mother tongue, student participation.

El presente estudio da cuenta del tipo de actividades desarrolladas por una maestra y la respuesta/participación de los estudiantes del grado noveno en esas actividades. Los objetivos de esta investigación fueron identificar y describir el tipo de actividades desarrolladas, la forma como los estudiantes responden a éstas y mostrar el uso de la lengua extranjera en el salón de clase. Para recolectar los datos se usó registro diario de y un diario de campo. Los resultados muestran que en el salón de clases la docente desarrolla doce tipos de actividades y que el porcentaje de uso de lengua extranjera es bajo.

Palabras clave: actividades de clase, lengua extranjera, lengua materna, participación estudiantil.

Introduction

It seems that the manner in which teaching activities are developed promotes or restrains students' use of the target language (L2) inside the classroom. Consequently, this issue has been a matter of attention and concern during my over five years teaching foreign languages (English and French). Furthermore, in the last two years, classroom observations in my teaching context have triggered research needs on the aforementioned issue. These observations showed that the use of English (mainly in public schools in Cali, Colombia) is not significant and that students' participation in English class is low. For instance, a study by Hernández Gaviria and Faustino (2006) revealed that Spanish is the language that predominates in the English classrooms in public schools in Cali and that teachers and students communicate in L2 when asking for short directions, answering questions, and participating in dialogues. Similarly, in an article published in 2010 in the newspaper El País1 and at the webpage of the Colombian Ministry of Education ("Bilingüismo aún," 2010), it is stated that both teachers and students have deficient levels of English, and the situation is worse with students from public schools. One of the interviewees, Dr. Cardenas from Universidad del Valle (Colombia), argued that among the causes of this backwardness are the unfavourable teaching conditions and teachers' unpreparedness to teach English. However, studies conducted in various English as a foreign language (EFL) settings (Akram & Malik, 2010; Peace Corps, 1989; Richards, 2006) argue that students' low English use is also attributable to the disconnected ways in which foundational skills are addressed in the different activities that are developed in language classes.

Contrary to what many authors state (Almarza Sánchez, 2000; Brown, 2007; Gocer, 2010; Harmer, 2007a; Hinkel, 2006), it appears that many teachers disregard or have found it difficult to integrate the four foundational language skills (speaking, writing, listening, and reading) into their language teaching activities. For instance, an activity that involves reading is not seen as a source for exploiting other language skills, which could foster a holistic use of language and superior student involvement. It appears that there exists a close relationship between the types of classroom activities teachers develop and students' participation in and responses to them.

Some authors defend the idea that activities must be developed in a way that fosters learners' active involvement (Harmer, 2007a, 2007b; Hinkel, 2006; Richards, 2006). As is known, language-teaching activities should aim to develop communicative skills (Klippel, 1984; Peace Corps, 1989; Richards, 2006), and activities should be developed in a way that shows each skill as a subset or constituent of a whole, the language. As a result, learning outcomes should improve if activities are carried out in such a way that they integrate various foundational language skills; if activities are meaningful for the students, they will feel more motivated to participate, and this will create an enriching teaching-learning process. Because of the connection between the teacher's activities and the students' responses to them, it is necessary to look at language teaching activities and their impact on students. Thus, this study aims at identifying and describing types of teaching activities, the way students respond to them and the ways the target language is used in the classroom.

This research was developed to fulfill some of the requirements for passing the course Classroom Research Seminar II, which is part of the syllabus of the BA in foreign languages (English-French) in the School of Language Sciences at Universidad del Valle (Colombia). Some of the purposes of the course are to acquaint pre-service teachers with research methods, instruments, techniques, and their future teaching environments. Pre-service teachers are also encouraged to reflect about possible research problems in order to ultimately report the findings in a semester final project.

Review of the Literature

Many scholars have addressed the question of classroom activities in the EFL classroom, students' participation and responses, and the ways that either L1 or L2 are used. All of these aspects are of the utmost relevance for the present study and will be further discussed next.

Teaching Activities

Richards and Schmidt (2010) define teaching activities as "any classroom procedure that requires students to use and practise their available language resources" (p. 9).

Richards (2006) contends that in communicative language teaching (CLT), activities have to include role-plays, group work, and projects with which fluent use of language can be promoted rather than focusing on formal aspects of language such as grammar. Because the main purpose of the teaching-learning process is to have students use the target language fluently, classroom activities must focus on negotiating meanings, correcting misunderstandings, and using strategies to avoid disruptions in communication. Richards also characterizes activities that focus on fluency as follows: "Reflect natural use of language, focus on achieving communication, require meaningful use of language, require the use of communication strategies, produce language that may not be predictable, and seek to link language use to context" (p. 14).

Equally, Riddell (2003) describes a group of activities that are useful for fostering language skills, grammar, and vocabulary, as well as the role of the teacher before and during each stage of a given activity. Riddell states that before an activity, teachers must identify the most suitable activity based on their class levels, their learners' average ages, class features and time available, and the targeted language aspects. Some suggestions during the activity are as follows: "Be varied in your choice of activities from lesson to lesson. Practice activities need to be carefully selected, and properly set up with instructions and examples. Practice activities should be as relevant and interesting as possible" (Riddell, 2003, pp. 94-95).

According to Klippel (1984), "activities for practising a foreign language have left the narrow path of purely structural and lexical training and have expanded into the fields of values education and personality building" (p. 6). He describes activities in terms of their topics, the speech acts involved, level, organisation, preparation, time, language focus, and educational aims. Klippel makes the following points about designing teaching activities:

Since foreign language teaching should help students achieve some kind of communicative skill in the foreign language, all situations in which real communication occurs naturally have to be taken advantage of and many more suitable ones have to be created. Two devices help the teacher in making up communicative activities: information gap and opinion gap. Information-gap exercises force the participants to exchange information in order to find a solution (e.g. reconstitute a text, solve a puzzle, write a summary). Opinion gaps are created by exercises incorporating controversial texts or ideas, which require the participants to describe and perhaps defend their views on these ideas. Another type of opinion gap activity can be organised by letting the participants share their feelings about an experience they have in common. (Klippel, 1984, p. 4)

Other points made by Klippel (1984) are that activities should help students recognize themselves in the target language, and for that to occur, the activities have to be meaningful and create students' interest, which will improve their performance.

Learning is more effective if the learners are actively involved in the process. Learner activity in a more literal sense of the word can also imply doing and making things; for example, producing a radio programme forces the students to read, write, and talk in the foreign language as well as letting them ‘play' with tape recorders, sound effects, and music. (Klippel, 1984, p. 5)

Klippel's (1984) conception of activities is in agreement with the view of skills integration that were mentioned earlier in this study and with Richards and Schmidt's (2010) definition of what EFL activities imply that learners will be doing. Thus, the question of teaching activities, as was stated earlier, is crucial in language teaching and learning. Accordingly, there are many more theoretical and practical documents that can be consulted by the novice teacher to become familiar with the theory and practice of activities or by the expert teacher to continue widening the insights on this overarching issue. Gunduz (2004), for instance, conducted a study in which the main purpose was to "investigate the effects of activity types on learners' language production in a classroom setting" (p. 31). Other relevant works are those of Allegra and Rodríguez (2010), Clutterbuck (1999), Gairns and Redman (1986), Granger (1998), Harmer (2007b), Hinojosa Cordero and Quinatoa Mullo (2012), Howard-Williams & Herd (1989), Nielsen Nino, (2010), and Seymour and Popova (2003). The aforementioned documents are very relevant because they contain practical and theoretical ideas for teaching the foundational and subsidiary language skills, that is, vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation.

Students' Participation/Response

Authors have addressed the matter of participation in both EFL and English as a second language (ESL) classrooms. As stated in a document by the Peace Corps (1989), participation is inextricably related to activities inasmuch as students' participation increases if the selected activities involve them. Solihah and Yusuf (n.d.) conducted a study in which they aimed to describe the quality of students' classroom participation and its factors. In their study, they observed an English teacher and 13 seventh-graders of a public junior high school in Bandung (Indonesia); the study reveals that students' participation in and contributions to activities were low and they preferred to keep silent; the teacher's control of the classroom processes and the students' lack of confidence in participating are dominant. In the same way, a study by Majid, Yeow, Ying, and Shyong (2010) sought to "explore students' perceptions of class participation and its benefits, barriers to their participation, and the motivational factors that may improve their class participation" (p. 1). The study was conducted with students who had graduated, but it shows important findings about the issue of classroom participation, and it also serves as a proof that concerns about this matter are present not only at the elementary and high school levels but in higher education as well. Majid et al. also found that:

a majority of the students agreed that class participation was helpful in their overall learning. It was interesting to note that over 90% of the students said that instead of talking in a big class, they usually preferred participating in small group discussions. They also indicated that they were more likely to participate in classes taught by friendly and approachable instructors. The major barriers to class participation, identified by the respondents, were: low English language proficiency, cultural barriers, shyness, and lack of confidence. (p. 1)

Language Use Inside the Classroom

The idea of no L1 use inside the language classroom is the product of the direct method, which appeared in the late 19th century. It appears that it was (and is still today) considered that if only the target language was used in the classroom, the teaching-learning process would have better outcomes, at least in terms of communication. Nonetheless, it is important to note that teachers should not see L1 use as a "sacrilege" to the learning process. Accordingly, Hamer (2007b) questions the ban on using L1, presents a series of the advantages and disadvantages of using L1 in L2 classrooms, and summarises how and when to use students' L1 in class. Harmer (2007a) maintains that:

The first thing to remember is that, especially at beginner levels, students are going to translate what is happening into their L1 whether teachers want them to or not. It is a natural process of learning a foreign language. On the other hand, an English-language classroom should have English in it, and as far as possible, there should be an English environment in the room, where English is heard and used as much of the time as possible. For that reason, it is advisable for teachers to use English as often as possible, and not to spend a long time talking in the students' L1. However, where teacher and students share the same L1 it would be foolish to deny its existence and potential value. (pp. 38-39)

To know more about language use inside the language classroom, one can review the studies by Hitotuzi (2006), Lasagabaster (2013), Muñoz Hernández (2005), and Sánchez, Pernía, Rivas, and Villalobos (2012).

Context of the Study

This project was carried out at a public high school in the city of Cali, Colombia. The pedagogical methods are oriented toward integral, inspiring development in which learning takes place in cooperation with others and the formative process is developed based on the values of the human being.

Regarding teaching English, the school has adopted the requirements of the National Bilingual Plan (NBP) 2004-2019, and the English teachers stated that they used the communicative approach. The students who were observed received three hours of English per week, and because of an agreement that the institution established with SENA (Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje [National Apprenticeship Service]), the students receive extra classes once a week; this is to reinforce their English skills and to train them with employment focus.

Participants

The group of participants was composed of 39 teenagers (20 female and 19 male between the ages of 14 and 17) and their teacher. The teacher holds a major in modern languages and a series of diplomas and certifications for teaching English. She has been teaching for 24 years, and at the time of the observations, she was a full-time teacher at the school where the study took place.

Method

To conduct this qualitative research, a review of research studies was carried out to shed light on the nature of ethnography, how to conduct classroom observation, daily field notes, and keeping observation records (Allwright & Bailey, 1991; Fernández Loya, 2002; Geertz, 1973; Gutiérrez Quintana, 2007; Hernández Sampieri, Fernández Collado, & Baptista Lucio, 1991; Nunan, 1992; Sandin, 2003). In regard to qualitative studies, Hernández Sampieri et al. (1991) state that they allow for deeper data and better contextualization of situations.

This is an ethnographic study, and in order to develop it, nonparticipant observation was conducted from January 26 to April 26, 2012. During this period, nine lessons were observed and recorded.

Procedure

To develop this ethnography, I rely mainly on Hernández Sampieri et al. (1991), and during my fieldwork, I made nine recorded observations. The initial stage of the research was devoted (with the guidance of my research tutor) to revising and consulting in order to build the conceptual framework. This allowed for familiarizing myself with the emic vocabulary, different research approaches, the methodological traditions, and developing group workshops with the aim of clarifying doubts. The second phase consisted of preparing and selecting aspects to observe, which paralleled the fieldwork with the nonparticipant observations, daily field notes, and the reflection diary keeping. In this phase, the research questions were also established: What activities does the teacher develop in order to promote the foundational and subsidiary language skills in the classroom? How do the students participate in and respond to the activities? What is the relationship between the activities developed and the L1/L2 use inside the classroom?

The third phase was devoted to constructing the body of the project, that is, the writing process. In the fourth phase, the observation records and daily field notes were refined and analysed. In this phase, the activity types and categories were also established. The fifth phase was mainly devoted to analysing those types and categories; during this period, there was a revision and rereading of all the materials as well as data coding in which three categories of data were processed: teaching activities, skills and language aspects, and students' participation and responses. A recoding process followed in order to reduce the categories to more concrete ones according to their frequency of appearance. Finally, the data were interpreted for the conclusion statement. Each of the aforementioned phases was done with the advice of my methodology course professor.

Data Analysis

During the nonparticipatory observations, the information was gathered through daily field notes and recordings. I later coded and classified the data, naming and grouping them by frequency of appearance. To do this, I used the Microsoft Word tool color text highlighter, which helped to better distinguish and establish the categories. The reflective diary was useful for registering impressions of what was being observed, reflecting on what was going well or poorly in the study, and compiling ideas for how to process and name the categories.

Findings

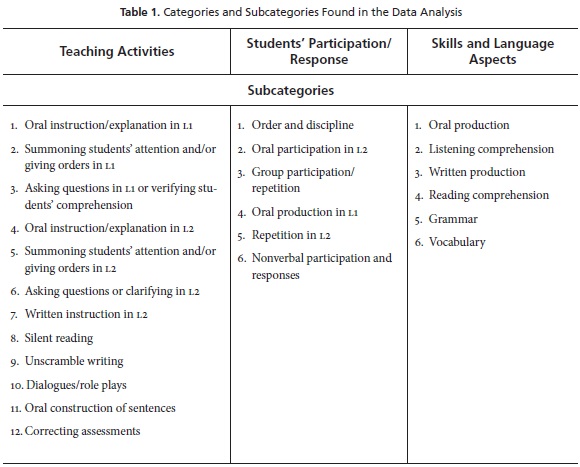

After the process described in the previous section, it was possible to identify three types of categories and subcategories, as shown in Table 1.

Teaching Activities

Here, activities refer to all realizations or practices that the teacher conducted inside the class during the nine observations and that suggest the use of any language or subsidiary skills. The following were the twelve teaching activities that were identified:

- Oral instruction/explanation in L1: This happened when the teacher spoke in Spanish to the students to illustrate and/or clarify information about the teaching, institutional information, and so forth:

- Summoning students' attention and/or giving orders in L1: When the teacher asked students to pay attention, keep silent, behave, and so on or when she asked them to do something:

Teacher: chicos, él viene observar la clase, él va estar el resto de la clase con nosotros [Guys, he's here to observe the class; he will stay with us for the rest of the class].

Teacher: No quiero que se hablen entre parejas porque cada pareja tiene un libro diferente [I don't want pairs to speak among you because each pair has a different book].

Later, after the teacher notices that students are talking too much, she asks them if they have already finished the exercise, to which they respond in the affirmative. Thus the teacher tells them: entonces todos me entregan los cuadernos [So all of you give me your notebooks].

- Asking questions in L1 or verifying students' comprehension: When the teacher talked to students to check if they had understood information or an instruction that had been given to them or given to obtain information from them:

- Oral instruction/explanation in L2: When the teacher used L2 to give directions or illustrate or clarify information about the teaching, institutional information, etc.:

- Summoning students' attention and/or giving orders in L2: When the teacher used L2 to ask for students' attention, ask them to keep silent and behave, etc. or when she ordered them to do or not to do something:

- Asking questions or clarifying in L2: When the teacher asked students questions and/or checked whether they had understood the information or instruction given to them:

- Written instruction in L2: When the teacher wrote any information or instruction on the whiteboard or on a sheet of paper in L2:

- Silent reading: The teacher gave the students books that contained stories. The reading was done sometimes individually and sometimes in pairs, and the students had to follow the teacher's instructions:

- Unscramble writing: The teacher wrote some scrambled sentences on the whiteboard, and the students had to work individually to write (unscramble) them on a sheet of paper, which took place during assessment processes:

- Dialogues/role plays: This occurred during assessment processes as follows: The students have to work in pairs or individually in order to create a conversation about any of the topics studied during the term. Each pair goes in front of the class and acts out a structured and predictable question-answer dialogue about their personal information, including like and dislikes. Unpaired students performed the dialogue with the teacher:

- Oral construction of sentences: The teacher, standing in front of the students, started a sentence and then chose a student and asked her/him to complete it. The student is helped by the teacher when necessary:

- Correcting assessments: After an assessment process, the teacher invited the whole class to review the answers. The teacher asked or started the statement, and the students participated, giving the correct answers orally.

Teacher: A ver...levanten la mano quienes no hicieron la tarea [Let's see...raise your hands those who didn't do the homework].

Teacher: Today, you're going to have reading practice; I'm going to bring books.

Teacher: Last week, I only received one work. I'm really disappointed, very bad homework. I told you you can work at home. You're going to have a bad grade...1! Finish the homework and gave [sic] me the workbook. You're really relaxed. Students: (Just whispers of concern).

Teacher: And you? When are you going to me? She went, she went; and you? Do you feel nervous about me?

On the whiteboard is the direction for a quiz: Write sentences with the following words:

1. don't - my - soda - like - friends.

2. are - from - where - you?

3. does - girl - the - not - study - here

4. favorite - English - subject - my - is

5. Live - do - where - you?

A student: Profe, ¿qué hay que hacer? [Teacher, what do we have to do?]. The teacher does not respond.

Teacher: Those are my books; you have to care for them. I love my books. The first one is this.

Students: (They just listen; everybody is silent, and then there were very low whispers).

Teacher: OK people, be quiet; you have to read the title. First, read the title; second, underline the unknown words; look up the unknown words in your dictionary; etc.

Teacher: ¿Qué van a encontrar allí? El verbo To Be, el verbo hablar, el verbo comer, etc. [What are you going to find in the reading? The verb to be, the verb to speak, the verb to eat, etc.].

Some of the books the students read were: Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson and The Crane's Gift by Steven and Megumi Biddle.

Teacher (orally): You have to write words with these words. Don't cheat please, don't cheat.

Students: Profe, ¿qué hay que hacer? [Teacher, what do we have to do?] (The teacher does not answer and continues writing on the whiteboard).

1. parents - home - are - at - today - my

2. The - don't - students - like - pets

3. They - why - here - are?

4. They - people - wonderful - are

5. me - please - help - teacher

A. What is your favorite place?

B. My favorite play is soccer.

A. No, no, place.

B. My favorite place is Palmeto.

A. Do you have pets?

B. Yes, I have three.

A. Where do you work?

B. I don't work, name.

A. Where do you study?

B. I study in...

A. What you favorite subject?

B. My favorite is English.

A. What is favorite singer?

B. My favorite singer is...

A. Umh! This is singer is amazing.

B. Do you see TV?

A. Yes

B. What is your favorite serie? (At this point, the teacher (in Spanish) asks the pair to stop because they are going off the topic).

Teacher: You are...(the students continue), you are very good people.

Teacher: I love dancing, do you love dancing? (to another student). Do you love dancing?

Student: I don't love dancing.

Teacher: OK, If you stay five minutes, I can correct the quiz. I will say the sentences as they are.

Students: (scream joyfully)

Teacher: Number one: My...

Students (orally): My - parents - are - at- home - today (claps and screams).

Teacher: Number two: The students...

Students: don't - like - pets (claps and screams).

Teacher: Why...

Students: why - are - they -here? (Claps and screams)

Teacher: They...

Students: They are - wonderful - people.

Teacher: (She just points to the sentence)

Student: Teacher help me please.

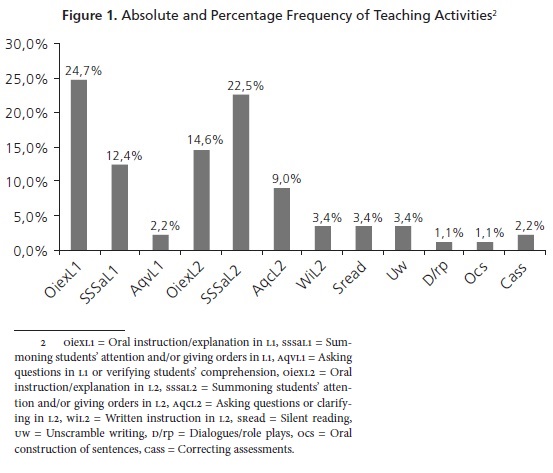

Some points to make about this category are as follows: The activity that was most practised is Oral instruction/explanation in L1, with an absolute frequency of 22 (24.7%). If other activities in L1 are added, L1 use frequency increases to 35 (39.3%). In contrast, certain L2 activities had a frequency of 54 (60.7%). In a sense, one could say that the activities genuinely promoted the target language use or that the teaching-learning process in this classroom is more developed in L2 than in L1. This is appealing, taking into account that in this particular context—a non-bilingual public school—there is evidence of lack of resources and materials (at least for teaching English) and that there is little need for target language use. Similarly, contrasting the subcategory Oral instruction/explanation in L1 with Oral instruction/explanation in L2, there is a gap in that the former appears 22 times and the latter 13 times. However, this must not be cause for concern because the reviewed literature states that it is appropriate to use L1 when giving instruction, clarifying, and so on, especially at beginner levels. Yet what one can lament is the few times Dialogues/role plays and Oral construction of sentences occurred. Figure 1 presents more details about the teaching activities.

Skills and Language Aspects

- Oral production: This took place mainly when the teacher developed activities such as dialogues, responses to comments, orders, explanations, and oral assessments, which could take the form of either student-student or student-teacher interactions.

- Listening comprehension: This skill was used when the teacher spoke in L2 and when she had students do role plays (dialogues, conversations).

- Written production: This occurred only during assessments, and students always worked individually when using this skill. For instance, the teacher asked the students to write a list of verbs and create sentences with them.

- Reading comprehension: This took place during assessments or in-class exercises. Either the teacher gave students a handout with a short story or tale or students copied an instruction from the whiteboard. The activity was individual, or sometimes in groups. For instance, students had to read while paying attention to verb conjugations (present, past, past participle), unknown words, and so forth. Students could use their dictionaries once they had finished the reading:

- Grammar: Students used this subsidiary skill when they were asked to unscramble sentences, making lists of verbs in the present and past participle tenses:

- Vocabulary: This subsidiary skill was utilized through readings, and it mainly occurred during assessments. It took place individually and in groups. Some of the texts the students read were: The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, Black Beard's Treasure by Jenny Dooley, and Love or Money by Rowena Akinyemi.

Student: Hello! Everybody.

Students: Hello!

Student: My name is JJ3 and ...

Another student: Teacher, can I make him a question?

Student: How old are you? (Repeats three times, but JJ does not answer because he does not understand).

(Seconds later) JJ?...My name is JJ

Another student: Hello! How old are you. My name is...grado noveno [ninth grade]. Do you /laIf/ Vallado?4

Teacher: Remember; I can help you, but I'm sorry, I am very angry with you. You don't need me; you don't want my help.

Student (during a dialogue): I /laIf/ in Vallado. I /laIf/.

Teacher (correcting him): I /lIv/. (The student stutters and hesitates because of the teacher's interruption).

Student: I live with my parents. My favorite pet, my fa...I am fifteen years old.

Teacher: Where are you from?

Student: I am from Cali.

Teacher (direction for a writing exercise written on the whiteboard): Write 15 verbs = present - past participle. Make 5 sentences in present - past participle with HE.5

(On the whiteboard): Exercise No. 2 with texts.

1. Read the three texts again and:

Look for: subject - verbs - predicates/complements

2. Look at the verbs and say what is its tense.

Teacher: Read the three texts again.

Students: What is again?

(On the whiteboard): Escribir el pasado simple y el pasado participio de los siguientes verbos [Write the simple past and past participle for the following verbs]: Put, play, fly, sing, dance, study, sleep, come, love, go, eat, drink.

Student: (During a reading exercise: What does it mean "come"?

Student: What does it mean "from"?

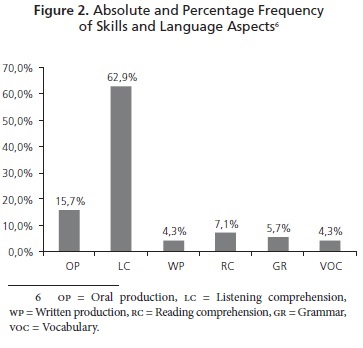

It is noteworthy that the most practiced skill in the classroom was listening at 62.9%; this was likely not intentional but a byproduct of the instruction process. It has to be considered, as was already mentioned, that during the observation process, the teacher used no technological devices to develop listening activities. This implies that the target language the students listened to was the teacher's or the other students'; thus the teacher's and classmates' inputs had a crucial role in the context that was observed. Figure 2 better describes this matter.

Students' Participation/Response

- Order/Discipline: Students remained calm, kept volumes low, remained silent, paid attention to the teacher, and so on. This student's response was closely related with assessment:

- Oral participation in L2: This sometimes occurred impromptu or spontaneously, and at other times, it was the product of the teacher's overt input, as an instruction, an order, a clarification, a correction or corrective feedback.

- Group participation/repetition in L2: When the whole class participates (most of the time) as result of the teacher's input.

- Oral production in L1: When students communicated in Spanish to ask for clarifications, answer questions, and so on:

- Repetition in L2: When students reproduced what the teacher had just said. Sometimes, students repeated to help the teacher keep the class calm.

- Nonverbal participation/response: When students participate through gestures or body language. They did this in order to follow the teacher demands, instructions, etc.

(During a silent reading): Latecomers continue entering the classroom in complete silence. By waving her head and hands, the teacher tells students to sit down. The students respond by body language too. Nobody speaks during the reading.

(Interacting with the teacher) Teacher: I love dancing, do you love dancing? (Teacher repeats) Do you love dancing?

Female students: I don't love dancing. (One student repeats) I don't love dancing.

(Whole class is creating sentences). The teacher continues encouraging the students to create more sentences. She has them repeat them, then she writes each sentence on the whiteboard): 6. They are very good soccer players. 7. My classmate is funny. 8. You are crazy people. 9. I love dancing.

Teacher (during a reading test): What's that?

Student: para traducir [For the translation].

Teacher: OK babies; come on, sit down.

Students (helping the teacher): Vea que sit down; sit down hombre. (Because the students could not remember the way to reproduce the whole sentences in English, they combined L1 and L2).

(Minutes later) Teacher (to a student who is misbehaving): Be quiet! F.

Student: Be quiet, be quiet F.

Teacher: Do you feel nervous about me?

(Student affirms by moving his head).

Teacher: Stop, be quiet! F and N come here. (The students obey the teacher).

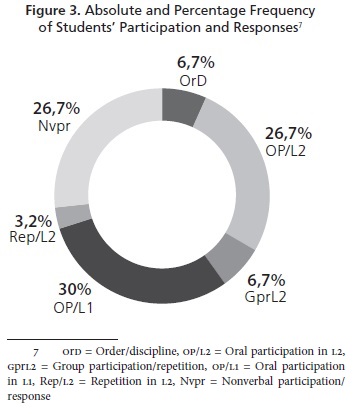

As was mentioned before, listening comprehension was the skill that took place in the classroom most often. This fact could be closely related to one of the ways the students most participated (responded), which was Oral participation in L2, with eight (26.7%) appearances. A possible interpretation here is that if the teacher used L2 in the classroom, the students were likely to use this input to communicate in L2 as well. Another aspect to note is the amount of Nonverbal participation/response, with an absolute frequency of eight (26.7%). This is undeniable proof that even though students sometimes do not participate or respond orally to the teacher or to other classmates, they do understand what is being said to or asked of them. See Figure 3 for more details on the students' participation and responses.

Other Findings

In the correlation between students' participation and responses and the activities that provoked them, this study found that if the teacher used L1 to communicate with the students, they were likely to respond or participate in L1. Additionally, if the teacher communicated in L2 and the students understood what she said but did not have the vocabulary or did not know or felt unsure about how to answer her in L2, they were likely to use nonverbal communication or body language to participate or respond.

Other important aspects are that group and individual participation were very low; this means that the teaching activities did not significantly involve students. Similarly, it cannot be affirmed that any activity or activities provoked students' indiscipline or misbehaviour; on the contrary, activities such as silent reading helped to keep students in order and calm.

Conclusions

The purposes of this study were the following: First, to identify and describe the types of teaching activities developed in a ninth-grade classroom. It was found that the teacher developed 12 types of activities, including activities that intended to present content (oral instructions/explanations in L1), control discipline (summoning students' attention and/or giving orders in L1), and assessing students' comprehension (asking questions in L1 or verifying students' comprehension). The second objective aimed at examining how the students responded to the teacher's activities. The results showed that students reacted in different ways, for instance, by following the teacher's instructions (e.g., Order/discipline) but they decided in which language to respond, for example, Oral repetition in L2 and Oral production in L1. The last research purpose was to explore how the target language was used in the classroom. The observations and data in Figure 3 indicate that although receptive skills—that is, listening comprehension (62.9%) and reading comprehension (7.1%)—received much more attention (70%), productive skills—oral production (15.7%) and writing production (4.3%)—were less emphasized (20%). As stated before, receptive skills took place when students heard the teacher talk (instructing them) in L2, when she had students listen to themselves in role plays (dialogues, conversations), and during readings during assessments or in-class exercises. In contrast, productive skills accordingly took place mainly when the teacher developed activities such as dialogues, when students responded to the teacher's comments, orders, etc., and during assessments in which students had to write lists of verbs and create sentences with them.

One of the implications of this study is that al- though there was significant use of the target language in the classroom, it was the teacher who dominated participation. This explains why receptive skills were predominant in the class that was observed, something that has been found in other studies elsewhere (Alvarado Rico, 2013; Davies, 2011; Johnson, 1995; Prieto Castillo, 2007; Urrutia León & Vega Cely, 2010).

It is important to acknowledge that receptive skills help students develop language proficiency but that teachers need to create better conditions for a balanced articulation of receptive and productive skills. Additionally, more work is needed to increase the use of the target language in the classroom. I do not oppose integrating L1 in foreign language classes, but its use must be pedagogically guided. It must be used for strategic purposes but must not dominate the classroom language environment. One call this study makes is for teachers to reflect on and design pedagogical strategies to involve their students and foster L2 communication in the classroom.

1The source text is in Spanish; it was translated into English by the author of the current research.

3A pseudonym for the student.

4Name of a neighbourhood.

5It was not possible to obtain the result of this exercise, and thus, no example is provided.

References

Akram, A., & Malik, A. (2010). Integration of language learning skills in second language acquisition. International Journal of Arts and Sciences, 3(14), 231-240. [ Links ]

Allegra, M. C., & Rodríguez, M. M. (2010). Actividades controladas para el aprendizaje significativo de la destreza de producción oral en inglés como LE [Controlled activities to develop meaningful oral English skills]. Revista ciencias de la educación, 20(35), 133-152. [ Links ]

Allwright, D., & Bailey, K. M. (1991). Focus on the language classroom: An introduction to classroom research for language teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Almarza Sánchez, M. Á. (2000). An approach to the integration of skills in English teaching. Didáctica (Lengua y Literatura), 12, 21-41. Retrieved from http://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/DIDA/article/view/DIDA0000110021A/19603. [ Links ]

Alvarado Rico, L. J. (2013). Identifying factors causing difficulties to productive skills among foreign languages learners. Opening Writing Doors Journal, 10(2), 54-76. [ Links ]

Bilingüismo aún no dice "yes" en Cali. (2010, August 22). El País de Cali. Retrieved from www.mineducacion.gov.co/observatorio/1722/article-244053.html. [ Links ]

Brown, H. D. (2007). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Clutterbuck, P. (1999). Lessons on the spot. Retrieved from http://www.blake.com.au/v/vspfiles/downloadables/l25_30min_english.pdf. [ Links ]

Davies, M. J. (2011). Increasing students' L2 usage: An analysis of teacher talk time and student talk time. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham. Retrieved from http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/documents/college-artslaw/cels/essays/languageteaching/daviesessay1tttessaybank.pdf. [ Links ]

Fernández Loya, C. (2002). Observación y auto-observación de clases [Observation and self-observation in class]. Cervantes, 2, 119-128. Retrieved from http://didacticaelesalvador2009.wikispaces.com/file/history/Observaci%C3%B3n+y+auto-observaci%C3%B3n+de+clases,+Carmelo+Fern%C3%A1ndez.pdf. [ Links ]

Gairns, R., & Redman, S. (1986). Working with words: A guide to teaching and learning vocabulary. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Geertz, C. (1973). La interpretación de las culturas [Cultures interpretation]. Barcelona, ES: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Gocer, A. (2010). A qualitative research on the teaching strategies and class applications of the high school teachers who teach English in Turkey as a foreign language. Education, 131(1), 196-219. [ Links ]

Granger, C. (1998). Play games with English 1: Teacher's resource book. Oxford, UK: Macmillan Heinemann. [ Links ]

Gunduz, M. (2004). Communicative orientation in the language class and the effect of activity types on interaction (Doctoral dissertation). University of Leicester, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez Quintana, E. (2007). Técnicas e instrumentos de observación de clases y su aplicación en el desarrollo de proyectos de investigación reflexiva en el aula y de autoevaluación del proceso docente [Techniques and instruments for classroom observation and their application in the design of reflective research projects and in self-evaluation of pedagogical processes]. In S. Pastor Cesteros & S. Roca Marín (Eds.), La evaluación en el aprendizaje y la enseñanza del español como LE/L2 (pp. 336-342). Alicante, ES: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante. Retrieved from http://cvc.cervantes.es/ensenanza/biblioteca_ele/asele/pdf/18/18_0336.pdf. [ Links ]

Harmer, J. (2007a). How to teach English (2nd ed.). London, UK: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Harmer, J. (2007b). The practice of English language teaching (4th ed.). Edinburgh, UK: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Hernández Gaviria, F., & Faustino, C. C. (2006). Un estudio sobre la enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras en colegios públicos de Cali [A study about foreign language teaching in public schools in Cali]. Lenguaje, 34, 217-250. [ Links ]

Hernández Sampieri, R., Fernández Collado, C., & Baptista Lucio, P. (1991). Metodología de la investigación [Research methodology]. México, MX: McGrawHill. [ Links ]

Hinkel, E. (2006). Current perspectives on teaching the four skills. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 109-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/40264513. [ Links ]

Hinojosa Cordero, M. F., & Quinatoa Mullo, S. A. (2012). Aplicación de técnicas para desarrollar las destrezas de listening and speaking de los estudiantes de quinto, sexto y séptimo [Application of techniques for developing listening and speaking English skills in fifth, sixth, and seventh graders] (Unpublished undergraduate monograph). Universidad Estatal de Bolívar, Ecuador. [ Links ]

Hitotuzi, N. (2006). The learner's mother tongue in the L2 learning-teaching symbiosis. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 7(1), 161-171. [ Links ]

Howard-Williams, D., & Herd, C. (1989). Word games with English plus. Oxford, UK: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. E. (1995). Understanding communication in second language classrooms. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Klippel, F. (1984). Keep talking: Communicative fluency activities for language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Lasagabaster, D. (2013). The use of the L1 in CLIL classes: The teachers' perspectives. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning (LACLIL), 6(2), 1-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2013.6.2.1. [ Links ]

Majid, S., Yeow, C. W., Ying, A., & Shyong, L. R. (2010). Enriching learning experience through class participation: A students' perspective. Cooperation and Collaboration in Teaching and Research: Trends in Library Information Studies Education. Retrieved from http://conf.euclid-lis.eu/index.php/IFLA2010/IFLA2010/paper/view/10/10. [ Links ]

Muñoz Hernández, C. A. (2005). Usos de lengua materna (L1) y lengua meta (L2) en un contexto de inmersión real [Mother (L1) and target (L2) language use in an immersion context] (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Indiana, United States. [ Links ]

Nielsen Nino, J. B. (2010). Actividades didácticas de motivación en el aula para la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera de los estudiantes de grado undécimo del Colegio Champagnat de Bogotá [Classroom motivational activities for teaching EFL to eleventh graders at Colegio Champagnat in Bogotá] (Unpublished undergraduate monograph). Universidad de La Salle, Colombia. [ Links ]

Nunan, D. (1992). Research methods in language learning. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Peace Corps. (1989). TEFL/TESL: Teaching English as a foreign or second language. Washington DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. [ Links ]

Prieto Castillo, C. Y. (2007). Improving eleventh graders' oral production in English class through cooperative learning strategies. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 8, 75-90. [ Links ]

Richards, J. C. (2006). Communicative language teaching today. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Richards, J. C., & Schmidt, R. (2010). Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics (4th ed.). London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Riddell, D. (2003). Teaching English as a foreign/second language. London, UK: Bookpoint. [ Links ]

Sánchez, L., Pernía, J., Rivas, J., & Villalobos, J. (2012). Uso de la lengua materna en una clase de inglés como lengua extranjera: un estudio de casos [The use of the first language in an English-as-a-foreign-language class: A case study]. Educación, Lenugaje y Sociedad, 9(9), 67-95. [ Links ]

Sandin, M. P. (2003). Investigación cualitativa en educación [Qualitative research in education]. Madrid, ES: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Seymour, D., & Popova, M. (2003). 700 classroom activities. Oxford, UK: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Solihah, I., & Yusuf, F. N. (n.d.). Classroom participation: A case of a junior high school students in EFL context. Retrieved from http://file.upi.edu/Direktori/FPBS/JUR._PEND._BAHASA_INGGRIS/197308162003121-FAZRI_NUR_YUSUF/Kumpulan_artikel--ppt/Paper_CONAPLIN_Participation_Fazri%26Intan.pdf. [ Links ]

Urrutia León, W., & Vega Cely, E. (2010). Encouraging teenagers to improve speaking skills through games in a Colombian public school. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 12(1), 11-31. [ Links ]

About the Author

Jefferson Caicedo is a fifth-year student in the School of Language Sciences at Universidad del Valle (Colombia). He has taught English and French for more than five years and has given talks at national and international events.

Acknowledgements

I thank Professor Omaira Vergara for her advice and Institución Eduactiva Henrique Olaya Herrera for allowing me to conduct the study reported on here. Last but not least, I appreciate the support of Professor José A. Alvarez for helping me make this study publishable, and "Xime-LDU" for encouraging me to keep going.