Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.18 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2016

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.48608

http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.48608

Novice Non-Native English Teachers' Reflections on Their Teacher Education Programmes and Their First Years of Teaching

Reflexiones de profesores novatos y no nativos del inglés sobre sus programas de formación y sus primeros años de instrucción

Sumru Akcan*

Boğaziçi University, Istanbul, Turkey

This article was received on January 27, 2015, and accepted on July 28, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Akcan, S. (2016). Novice non-native English teachers' reflections on their teacher education programmes and their first years of teaching. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 18(1), 55-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.48608.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This study investigates novice non-native English teachers' opinions about the effectiveness of their teacher education programme and the challenges during their initial years of teaching. The results of a survey administered to fifty-five novice teachers and follow-up interviews identify strengths and weaknesses in their teacher education programme and catalogue the difficulties they faced when they star-ted to teach. The study found significant differences between the content of novice teachers' academic courses in their teacher education programme and the conditions they experienced in classrooms. The major challenges of their first years of teaching were related to lesson delivery, managing behaviour, unmotivated students, and students with learning disabilities. The article includes suggestions to prepare teachers for the actualities of working in schools.

Key words: In-service teacher development, non-native English teachers, novice teachers, teacher education programmes.

Este estudio se centra en las opiniones de profesores principiantes de inglés, no nativos, sobre la eficacia de sus programas de formación como profesores y los retos durante sus primeros años trabajando. Los resultados de una encuesta administrada a cincuenta y cinco profesores principiantes y entrevistas posteriores permiten identificar fortalezas y debilidades en el programa de formación del profesorado y catalogar las dificultades que tuvieron que afrontar en el comienzo de su carrera docente. Se encontraron diferencias significativas entre el contenido de los cursos académicos de los profesores principiantes en su programa educativo y las condiciones experimentadas en sus clases. Los retos principales de sus primeros años como profesores tienen que ver con la impartición de la lección, la gestión de la conducta, el alumnado desmotivado y alumnos con dificultades de aprendizaje. El artículo incluye sugerencias para preparar a los profesores para las realidades del trabajo en las escuelas.

Palabras clave: formación permanente del profesorado, profesores de inglés no nativos, profesores principiantes, programas de formación del profesorado.

Introduction

This study investigates the opinions of Turkish novice English teachers about the effectiveness of their teacher education programme in light of the challenges they have experienced in their first years of teaching. Novice teachers, according to Farrell (2012), have started to teach English within three years of completing their language teacher education programme. Veenman (1984) characterizes their first teaching experience as a type of “reality shock.” Newly qualified teachers might find themselves in a struggle for survival as they strive to adapt to an unfamiliar professional community in their induction years.

The first few years of teaching are a critical time for professional development (Farrell, 2009; Warford & Reeves, 2003). During this period, novice teachers either strengthen the belief that they will become competent teachers or they leave the profession (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2007). For the novice English teacher, challenges may include feelings of stress (Mann, 2008); the potential for misunderstandings in a culturally diverse classroom (Hooker, 2003); and isolation leading to loneliness and frustration (Numrich, 1996). Bullough, Knowles, and Crow (1991) noted that new teachers' initial concerns are usually about relationships with students, problems of classroom management, and unfamiliar instructional methods. Despite the good intentions and thoughtful planning of teacher education programmes, the first years of teaching have long-term implications for job satisfaction and length of career (Cochran-Smith, 2004; Darling-Hammond, 2003).

The phenomenon of novice teachers taking on the characteristics of existing teachers is known as “teacher socialization.” Teacher induction programmes aim to provide systematic and sustained assistance, specifically for beginning teachers in the early years of their profession for at least one school year. The new teachers begin to understand the school culture and the needs of students (Huling-Austin, 1990). Once they are members of the school community, they embrace the rules and expectations created by the veterans around them and gradually they adopt the same practices (Bliss & Reck, 1991; Shin, 2012; Zeichner & Gore, 1990). Learning about teaching is a situated process; the new teacher is socialized into a “community of practice” in which novices “move toward full participation in the sociocultural practices of a community [and gradually they] learn about the relations between newcomers and old-timers, and about activities, identities, artefacts, and communities of knowledge and practice” (Lave & Wenger, 1991, p. 29).

Senom, Zakaria, and Shah (2013) investigated the challenges faced by novice English as second language (ESL) teachers in Malaysia in the early years of teaching. This nationwide large-scale study examined novice teachers' socialization experiences. The data related to socialization problems were categorized into four groups: those concerning students, school community, the teaching profession, and parents. The problems concerning the students included their lack of interest in learning, misbehaviour, lack of discipline, and negative attitude towards the learning of English. Problems concerning the school community included the burden of teaching assignments and administrative responsibilities, high expectations, lack of support and guidance, isolation, and school politics. Problems concerning the teaching profession included the discovery that their teacher preparation programme had been inadequate, fatigue, time-consuming lesson planning, and the application of pedagogical theory to classroom practice. Problems concerning parents stemmed mostly from the high expectations that parents had for their children and their children's teacher. Despite the struggles, the novice teachers also found pleasure in the process of becoming a teacher and rewards in the form of student learning. These and the guidance they received from colleagues and administrators provided the motivation to remain in the profession.

Tarone and Allwright (2005) claim that the “differences between the academic course content in language teacher preparation programmes and the real conditions that novice language teachers are faced with in the language classroom appear to set up a gap that cannot be bridged by beginning teacher learners” (p. 12). One might ask how second language teacher education programmes can minimize the gap and prepare teacher candidates for the conditions they will find when they get a teaching job.

Farrell (2012) also argues that one of the reasons why young teachers leave the profession is that pre-service teacher preparation and in-service teacher development are not aligned. Novice teachers suddenly lose contact with their teacher educators just when they feel they must meet the performance standards expected of their more experienced colleagues. Such expectations include the necessities of lesson planning, lesson delivery, and classroom management. Other than their own resources, they have only the support and guidance of fellow teachers and administrators, which may or may not be forthcoming.

Invariably, beginning teachers must reconcile the pedagogy espoused in their university courses with the reality of teaching. In doing so, they are likely to encounter a set of norms and behaviours that clash with their previous experiences (Sabar, 2004; Scherff, 2008). Johnson (1996) reported that second language (L2) teacher education programmes are often criticised because they do not convey the sort of knowledge that teachers need most when preparing and teaching lessons in real classrooms. Novice teachers complain that in teacher education programmes they got too much theory and too little practice.

Richards (1998) explained that novice teachers do not automatically apply the knowledge they received in preparation courses because as teachers they have to construct and reconstruct “new knowledge and theory through participating in specific social contexts and engaging in particular types of activities and processes” (p. 164). On reflection, novice teachers found that practice teaching experiences that approximated “real” teaching were the most helpful part of their preparation programmes (Atay, 2007; Faez & Valeo, 2012). Faez and Valeo (2012) found that novice teachers of English increased their perceptions of efficacy as they gained experience in the classroom. The key issue in second language teacher education, then, is what teachers need to learn most and how their learning can have a beneficial impact on their future teaching practice.

The purpose of this study was to investigate novice English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers' perceptions of their preparedness to teach and the challenges they encountered in their first years of teaching in primary and secondary schools. The research questions of this study were:

- What are novice Turkish EFL teachers' opinions about their teacher education programmes?

- What parts of a language teacher education programme have novice Turkish EFL teachers found useful and why?

- What concerns and difficulties do novice Turkish EFL teachers have in their first year of teaching in the Turkish context?

Method

The study is an exploratory case study. The exploratory process gives way to collect data and allows patterns to emerge to define problems and explain causal links in real-life interventions. Exploring can include activities such as providing information, giving reasons, or making a causal statement (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998; Patton, 1990; Yin, 1994). This study is specific to a concern emerged in a context and aims to explore the novice teachers' attitudes towards their teacher education programme and the challenges in the first years of teaching.

The Context

The Foreign Language Education department in the Faculty of Education at a well-known English-medium university in Istanbul (Turkey) aims to prepare EFL teachers to teach in primary, secondary, and high schools. Prospective English teachers are provided with a foundation in theoretical and applied methodology through courses in linguistics and literature, the teaching of grammar and the four basic language skills, principles of first and second language acquisition, materials development, syllabus design, language testing, and approaches to foreign language teaching. The programme offers courses such as School Experience and Teaching Practicum in cooperating schools. Teaching Practicum places each fourth-year student in classrooms with three experienced teachers at three different grade levels in various state and private schools. A university supervisor from the department provides additional supervision and support. The student teachers visit the schools regularly and observe lessons taught by the three cooperating teachers. In the course of the practicum they observe for 45 hours and teach six 40-45 minute lessons. A cooperating teacher observes each student-taught lesson and provides feedback. The university supervisor and a cooperating teacher together evaluate each student's performance and provide oral and written feedback. The cooperating teachers are selected by the school administration. Although they are chosen for their experience and willingness to work with student teachers, they do not receive any formal training in supervision.

The Participants

The Turkish education system is under the supervision of the Ministry of National Education. Education is compulsory from ages 6 to 14 and it is free in public schools. In Turkey, there are public and private schools at the primary, secondary, and high school levels. English language instruction starts at Grade 2 in public schools and at kindergarten (3 to 4 years-old) in private schools. Participants in the study included 55 novice EFL teachers teaching at public and private primary, secondary, and high schools in the Marmara region (North-West) of Turkey. Twenty-nine teachers were primarily working with young learners (K-4), and the remaining 26 teachers were teaching in secondary and high school levels. All had less than three years of teaching experience after having graduated from a foreign language teacher education programme. Of the 55 participants, 50 were female and five were male. Their ages ranged from 23 to 27 years. They comprised a homogeneous group in terms of teacher training, language learning experience, and proficiency in English.

Data Collection and Analysis

The participants filled out a questionnaire composed of both open-ended and closed-ended questions. The researcher used the questionnaire called Survey of Teacher Education Programs (STEP), which was developed by Williams-Pettway (2005) for the purpose of gathering data concerning teachers' satisfaction with their teacher education programme (see Appendix). The data collection took place in the academic year of 2012-2013. It is organized around components of the National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education's accreditation process in the US, such as knowledge, skills, dispositions, field experiences, and quality of instruction. The researcher, with the help of expert input, adapted the questionnaire to the Turkish context and added seven open-ended questions that inquired specifically about the structure and content of the teacher education programme and participants' concerns during their first years of teaching. The questionnaire was adapted based on the teaching competencies of the Ministry of National Education in Turkey and then the questionnaire was evaluated by the experts (academics) who were specialized in the fields of teacher education and language teaching. Lastly, the questionnaire was revised based on their feedback and comments. Out of fifty-five teachers, fifteen volunteer teachers also participated in focus group interviews for the purpose of gathering more detailed information about their concerns and difficulties. The focus group interviews were run with a group of three to four teachers.

Responses to the closed-ended items were examined for frequency and percentages, and responses to the open-ended questions focus group interviews were analysed for content. The constant comparative method was used (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998) for the purpose of identifying themes. An interpretive, naturalistic method was used for the purpose of interpreting the teachers' experiences (Gall, Borg, & Gall, 1996).

Findings

The Teacher Education Programme

All the participating novice teachers agreed that their teacher education programme provided them with a good foundation in English language teaching. However, they thought that there was more emphasis on theory rather than practice and that theory and practice were not integrated in the programme. Asked to identify the strengths of the programme, 85% (47 teachers) of the teachers said that the practice teaching experience in a school setting gave them an opportunity to test their knowledge and skills at different grade levels, requiring them to deal with different student characteristics; 77% (43 teachers) said that the teacher education programme stimulated critical thinking and problem solving in context; and 88% (48 teachers) said that the programme helped them to learn a variety of teaching strategies and how to adjust teaching methods to the purpose of a lesson.

A majority of the teachers emphasized the need for more practice teaching, starting early and being offered throughout the programme rather than saving it until the final year. Furthermore, they wished they had had more teaching opportunities in young learner classrooms, including kindergarten, so that they could better learn to cope with the difficulties unique to teaching at that level. They felt the need for better instruction on dealing with classroom management problems, and they believed that they should have been offered more practical information about teaching students with learning disabilities.

In addition to practice teaching in classrooms, there had been opportunities for peer teaching in the university classroom, and the teachers considered this to be a valuable introduction to teaching methods. All 55 teachers had the peer teaching experience since “peer teaching” is one of the main requirements of the methodology courses in the teacher education programme. The teachers integrated their theoretical knowledge to practice through peer teaching sessions in their courses. Some of their statements are quoted below:

To be able to have the opportunity of peer teaching was one of the most useful experiences in my university education. (Ayşen)

By observing our peers and reflecting on their teaching performance, we learned not only how to observe but also reflect upon their teaching which we can use later on our own teaching skills. (Zeynep)

It helped me to evaluate my own teaching and see my strengths and weaknesses. (Ece)

Peer teaching helped us share our ideas and respond[ing] to my peers' reactions improved my thinking and deep understanding. It helped me to see different ways of doing things in other people's classrooms. (Serkan)

I had the opportunity to put into practice what I learned. But it was a little bit artificial as they were not real students but my friends. Lack of authenticity is the main problem in peer teaching. (Cansu)

Although the teachers valued peer teaching, they also knew that teaching in real classrooms was completely different. All of the teachers emphasized the importance of the School Experience and Teaching Practicum courses which were offered in the last year of the programme.

In their appraisal of university supervisors and cooperating teachers, 74% (41 teachers) of the novice teachers thought that their cooperating teachers had been influential and resourceful; 85% (47 teachers) thought that their university supervisor had provided clear feedback and suggestions; 77% (43 teachers) thought that the university supervisor and cooperating teacher had collaborated with them to evaluate their performance in the classroom. However, they reported that their university supervisors had little or no teaching experience in primary and secondary schools and thus had insufficient practical knowledge of real classroom practice. Some of what they said included:

I think it will be more effective if instructors have teaching experiences, so students can benefit from their experiences. (Mehtap)

Our instructors should learn more about the real schools and their situations in order to prepare us better as teachers. (Didem)

In their appraisal of coursework, 85% mentioned that their teachers had used appropriate instructional materials and demonstrated enthusiasm when teaching. However, in addition to the course content of the practicum course, they wished that their teachers had offered more explicit guidance to help them improve their language proficiency. They suggested that watching and discussing video recordings of lessons in real classrooms would be helpful, and that projects directly related to the content of the Ministry of Education's English language curriculum would have helped them to become more familiar with it.

The First Years of Teaching

The greatest challenge of the first years of teaching was classroom management. For this reason, most of the teachers chose activities such as drills and dictation, which restrict behaviour and minimize potential problems. Some of the teachers drew attention to the problems of managing behaviour in classrooms for young learners. Their comments included:

It is not easy to make group or pair work with young learners. At university we . . . included group work in our lesson plans. But in real life it does not work well because managing little kids in group work creates chaos in class. Now I usually prefer drills, dictation and role-playing in my classes.

Honestly, I must say that I cannot use any of the activities that I learned at university. I should follow the teacher books. . . . Also, I should focus on grammar and vocabulary because the exam period is coming up. (Merve)

My main problem was classroom management. I could not decide how to respond to specific misbehaviours. . . . I think classroom management is a skill that improves through experience. (Zehra)

Classroom management and motivating students seem to be harder than one can think when you are not in an actual classroom. (Şeyma)

The participating teachers also experienced difficulty in the implementation of the communicative approach in their classes. They explained in their teacher education programme they had learned and practiced the communicative approach for the teaching of English but that they were not able to use communicative methods in their classrooms because their classrooms were too crowded and they were expected—in the short time available—to prepare their students for national examinations. It was not possible in crowded classrooms to do group work, but most could get their students working in pairs. Their method of checking comprehension was to ask questions and receive answers. Some had tried to use discussions to motivate students to express themselves in English, but when the students' proficiency was not sufficient to maintain a discussion, the teachers resorted to drills to teach certain phrases.

Other difficulties included unmotivated students and students with learning disabilities. The majority of the teachers stated that they did not know how to deal with students who have learning disabilities. They were also lack of skills and strategies that could be used when their students were unwilling to learn and had behaviour problems. To cope with these difficulties, the teachers asked for help from experienced colleagues and sought out books and articles about effective teaching strategies. One of the teachers (Ebru) expressed her gratitude towards her school by noting that: “The school administration, the counselling department and my colleagues helped and guided me in every difficulty I had. I wouldn't have survived my first year without their support.”

Suggestions for Improving the Teacher Education Programme

The novice teachers made suggestions to improve the quality of the teacher education programme that they all graduated from. They thought that exchange programmes, such as the Erasmus programme (European Community Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students) would be helpful, or an online environment in which teacher candidates could interact with teacher candidates in other countries, an innovation that would help improve their communication skills as it helped to broaden their understanding of education. Erasmus is a European Union student exchange programme at the tertiary level in which teacher candidates take courses and receive training for one semester or a year at the host institution. With this opportunity, the teacher candidates can improve their language skills and increase their knowledge towards other cultures.

This study also indicated that most of the teachers wanted to be better informed about the conditions they would encounter as novice teachers, especially the challenges of working in crowded and underfunded state schools. They mentioned the need for more explicit guidance from university supervisors and mentors, both to improve their teaching skills and to develop their language proficiency. The teachers appreciated feedback about their classroom language use and the ways to improve their English language proficiency. They wished to hear more from their mentor teachers about their classroom language use to be able to use the target language more spontaneously for a more enriched interaction in the classroom.

The novice teachers reported that some of the teachers to whose classrooms they were assigned were neglectful of the teacher trainees they were supposed to help. Hence these novice teachers recommended training and a better selection process to identify interested and capable mentors. Orland (2001) made the following statement about mentor teachers as teacher educators: “learning to become a mentor is a conscious process . . . and does not emerge naturally from being a good teacher” (p. 75). They need to have more preparation for supervision and school administrators should be more careful in assigning mentor teachers for the practice teaching programmes as mentors for pre-service teachers.

As might be expected, other suggestions addressed issues that had also been identified as weaknesses in the programme: a practical classroom management course, the use of video recordings of situations in actual classrooms, and how to work with learning disabled students.

Discussion and Conclusion

The novice teachers in this study reported that there was more emphasis on theory rather than practice in the teacher education programme. The teachers emphasized the need for more practice in the programme, starting the first year. It is a paramount responsibility of teacher educators to connect generalized theory with the specifics of practice. This should be the goal of the practicum, the preparation of teacher candidates for classroom realities. Since the teacher candidates, as a rule, do not know exactly where they will get a teaching job, it is important that they develop the ability to adapt their generalized knowledge and skills to classrooms at different levels. Even though the novice teachers in this study had a rich theoretical education with practical experiences thrown in, their primary concerns when they started to teach were different; they had to learn quickly how to manage unruly student behaviour, and they were given the priority of covering the required material in preparation for national examinations.

This study showed that the novice teachers' initial concerns and challenges in the first years of their teaching are similar to the early studies in the field (Farrell, 2009; Bullough et al., 1991; Senom et al., 2013; Warfood & Reeves, 2003). In the present study, the teachers' concerns are primarily related to classroom management, implementation of the communicative approach in classrooms, unmotivated students, and students with learning disabilities. The novice teachers also reported that their relationships with cooperating teachers could have been more fruitful when they were student teachers. The cooperating teachers could have been more influential and resourceful by providing more time to give feedback and establishing an environment in which the student teachers question and reflect on their own teaching.

Akcan and Tatar (2010) had conducted an earlier study in the teacher education programme from which these novice teachers had graduated. The purpose of the study was to investigate the content of feedback given to teacher candidates by university supervisors and cooperating (mentor) teachers during supervisory conferences. They found that the feedback the university supervisors gave in post-lesson conferences with student teachers tended to promote reflection and self-evaluation whereas the feedback given by the cooperating teachers was more prescriptive and directive. The cooperating teachers contributed to a one-way flow of direct suggestions about classroom practice that discouraged any dialogue between the student teacher and themselves.

Considering this finding, school administrators, with the guidance of university supervisors, should be more careful when matching student teachers and cooperating teachers. A short supervision training programme for mentor teachers can be conducted by university supervisors to help them with their supervisory roles. Studies have shown that when cooperating teachers are better prepared for their supervisory roles, teacher candidates develop more positive attitudes towards teaching (Guyton & McIntyre, 1990).

Starting teachers need positive support (Brannan & Bleistein, 2012; Villani, 2002), and the use of support groups is one way to provide it. Online support groups through e-mail and discussion boards can provide support networks that help teachers with similar concerns to communicate with one another and engage in collaborative reflection (Merseth, 1991). A continuing relationship with peers and a university supervisor after graduation and during the first year of teaching would also be helpful.

As a final remark, there is a need to collect more data on the teaching experiences of graduates from teacher education programmes in general. Baecher (2012) believes that the lack of data may be preventing TESOL programmes from preparing teacher candidates to work effectively with English language learners. Similarly, Farrell (2008) has characterized the personal, social, and psychological demands faced by novice English teachers as they struggle to adapt to the realities of their work. Their feedback is invaluable as we undertake to meet the needs of teachers and learners in teacher education programmes.

References

Akcan, S., & Tatar, S. (2010). An investigation of the nature of feedback given to pre-service English teachers during their practice teaching experience. Teacher Development, 14(2), 153-172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2010.494495. [ Links ]

Atay, D. (2007). Beginning teacher efficacy and the practicum in an EFL context. Teacher Development, 11(2), 203-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13664530701414720. [ Links ]

Baecher, L. (2012). Feedback from the field: What novice preK-12 ESL teachers want to tell TESOL teacher educators. TESOL Quarterly, 46(3), 578-588. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tesq.43. [ Links ]

Bliss, L. B., & Reck, U. M. (1991). PROFILE: An instrument for gathering data in teacher socialization studies. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Eastern Educational Research Association. Boston, USA. [ Links ]

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (1998). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Brannan, D., & Bleistein, T. (2012). Novice ESOL teachers' perceptions of social support networks. TESOL Quarterly, 46(3), 519-541. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tesq.40. [ Links ]

Bullough, R. V., Knowles, J. G., & Crow, N. A. (1991). Emerging as a teacher. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cochran-Smith, M. (2004). Editorial: The problem of teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 55(4), 295-299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022487104268057. [ Links ]

Darling-Hammond, L. (2003). Keeping good teachers: Why it matters and what leaders can do. Educational Leadership, 60(8), 6-13. [ Links ]

Faez, F., & Valeo, A. (2012). TESOL teacher education: Novice teachers' perceptions of their preparedness and efficacy in the classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 46(3), 450-471. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tesq.37. [ Links ]

Farrell, T. S. C. (Ed.). (2008). Novice language teachers: Insights and perspectives for the first year. London, UK: Equinox. [ Links ]

Farrell, T. S. C. (2009). The novice teacher experience. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp. 182-189). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Farrell, T. S. C. (2012). Novice-service language teacher development: Bridging the gap between pre-service and in-service education and development. TESOL Quarterly, 46(3), 435-449. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tesq.36. [ Links ]

Gall, M. D., Borg, W. R., & Gall, J. P. (1996). Educational research: An introduction (6th ed.). White Plains, NY: Longman. [ Links ]

Guyton, E., & McIntyre, D. J. (1990). Student teaching and school experiences. In W. R. Houston, M. Haberman, & J. Sikula (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education (1st ed.). (pp. 514-534), New York, NY: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Hooker, J. (2003). Working across cultures. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Huling-Austin, L. (1990). Teacher induction programs and interships. In W. R. Houston, M. Haberman, & J. Sikula (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education (1st ed.). (pp. 535-548). New York, NY: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. E. (1996). The vision versus the reality: The tensions of the TESOL Practicum. In D. Freeman & J. C. Richards (Eds.), Teacher learning in language teaching (pp. 30-49). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355. [ Links ]

Mann, S. (2008). Teachers' use of metaphor in making sense of the first year of teaching. In T. S. C. Farrell (Ed.), Novice language teachers: Insights and perspectives for the first years (11-28). London, UK: Equinox. [ Links ]

Merseth, K. K. (1991). Supporting beginning teachers with computer networks. Journal of Teacher Education, 42(2), 140-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002248719104200207. [ Links ]

National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education. (2002). Professional standards for the accreditation of schools, colleges, and departments of education. Washington, DC: Author. [ Links ]

Numrich, C. (1996). On becoming a language teacher: Insights from diary studies. TESOL Quarterly, 30(1), 131-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3587610. [ Links ]

Orland, L. (2001). Reading a mentoring situation: One aspect of learning to mentor. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(1), 75-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00039-1. [ Links ]

Patton, Q. M. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Richards, J. C. (1998). Beyond training: Perspectives on language teacher education. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sabar, N. (2004). From heaven to reality through crisis: Novice teachers as migrants. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 145-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.09.007. [ Links ]

Scherff, L. (2008). Disavowed: The stories of two novice teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(5), 1317-1332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.06.002. [ Links ]

Senom, F., Zakaria, A. R., & Shah, S. S. A. (2013). Novice teachers' challenges and survival: Where do Malaysian ESL teachers stand? American Journal of Educational Research, 1(4), 119-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.12691/education-1-4-2. [ Links ]

Shin, S. K. (2012). "It cannot be done alone": The socialization of novice English teachers in South Korea. TESOL Quarterly, 46(3), 542-567. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tesq.41. [ Links ]

Tarone, E., & Allwright, D. (2005). Second language teacher learning and student second language learning: Shaping the knowledge base. In D. J. Tedick (Ed.), Second language teacher education: International perspectives (pp. 5-23). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2007). The differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(6), 944-956. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.05.003. [ Links ]

Veenman, S. (1984). Perceived problems of beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 54(2), 143-178. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543054002143. [ Links ]

Villani, S. (2002). Mentoring programs for new teachers: Models of induction and support. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. [ Links ]

Warford, M. K., & Reeves, J. (2003). Falling into it: Novice TESOL teacher thinking. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 9(1), 47-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1354060032000049904. [ Links ]

Williams-Pettway, M. L. (2005). Novice teachers' assessment of their teacher education programs (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Auburn University, USA. [ Links ]

Yin, R. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K., & Gore, J. (1989). Teacher socialization. In W. R. Houston, M. Haberman, & J. Sikula (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education (1st ed.). (pp. 329-348). New York, NY: Macmillan. [ Links ]

About the Author

Sumru Akcan is an associate professor in the Department of Foreign Language Education at Boğaziçi University (Turkey). She holds an MA in English as a Second Language (University of Cincinnati, USA) and a PhD in Second Language Acquisition and Teaching (University of Arizona, USA). Her research focuses on teacher education.

Appendix: Questionnaire for Novice Teachers

Survey of Novice Language Teachers Who Completed Their Teacher Education Programmes

Data collected from this survey will be analysed to learn more about your teacher preparation experiences. Participants will not be identified.

Thank you.

Part 1. Demographics

Please circle your answers or complete the information as appropriate.

Name of the educational institution where you are now teaching:

Status of the educational institution (State vs. Private):

The high school you graduated from:

GPA (Bachelor's degree program):

Female ( ) Male ( ) Your age: ______

- At what level are you presently teaching?

- Early Childhood & Elementary (K-4)

- Secondary and High School (5-12)

- For how many years have you been teaching since you graduated from your teacher education programme (including the current year)?

- One year

- Two years

- Three years

- More than three years

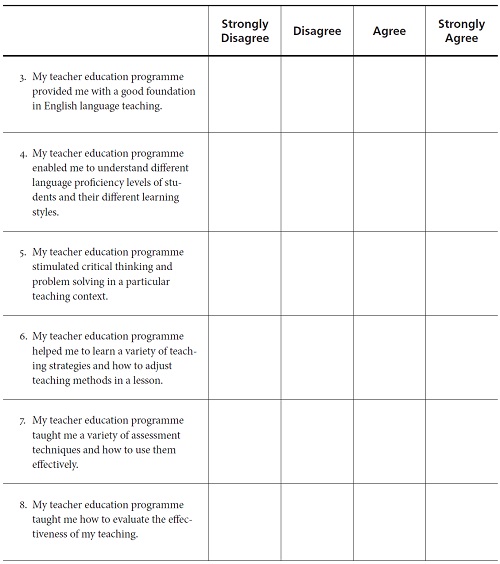

Part 2. Knowledge, Skills and Dispositions*

*Dispositions—The values, commitments, and professional ethics that influence behaviours toward students, families, colleagues, and communities and affect student learning, motivation, and development as well as the educator's own professional growth. Also, dispositions are guided by beliefs and attitudes related to values such as caring, fairness, honesty, responsibility, and social justice (National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education, 2002).

Indicate the extent of your agreement by selecting and putting a tick (☑) in the table below.

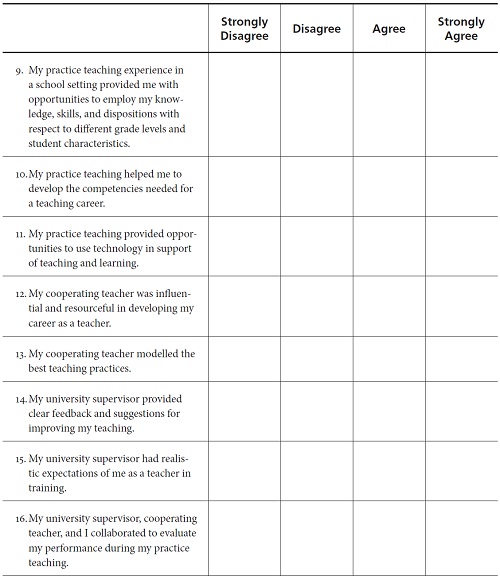

Part 3. Field Experiences and Practice Teaching

Indicate the extent of your agreement by selecting and putting a tick (☑) in the table below.

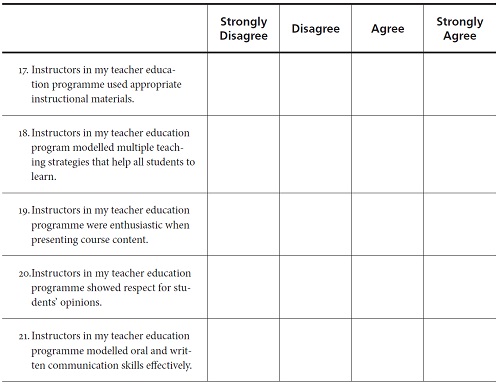

Part 4. Quality of Instruction

Indicate the extent of your agreement by selecting and putting a tick (☑) in the table below.

Part 5. Open-ended questions

Your brief responses are much appreciated.

22. Identify three major strengths and/or weaknesses of your teacher education programme.

23. Suggest two or more ways to strengthen your teacher education programme.

24. Circle the response that best describes your level of satisfaction with your teacher education programme.

- Excellent

- Good

- Fair

- Poor

Comment:

25. Which method(s) do you often use in your lessons? (You may circle more than one response.)

- Audiolingual method

- Communicative language teaching

- Content-Based language instruction

- Other: (please indicate)

Comment:

26. Which technique(s) do you often use in your lessons? (You may circle more than one response.)

- Role-playing

- Discussion

- Pair-work

- Group work

- Drills

- Other: (please indicate)

Comment:

27. If there are any methods or techniques that you cannot use in your lessons for reasons such as classroom environment, student characteristics, etc., please explain the difficulty and the reasons.

28. Did the peer teaching experiences in your methodology courses contribute to the improvement of your teaching skills? If so, in what ways? If not, why not?

29. Have you experienced any particular problem or challenge during your first few years of teaching? Please specify the problem, the cause, and, if appropriate, how you responded to the challenge.

30. Do you have any suggestions for improving the quality of the teacher education programme? Please be specific.

31. What advice would you give to teacher candidates who will soon graduate and start to teach?