Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.18 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2016

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.49592

http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.49592

Strategies Instruction to Improve the Preparation for English Oral Exams*

Instrucción en estrategias para mejorar la preparación para las pruebas orales en inglés

José Vicente Abad**

Paula Andrea Alzate***

Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó, Medellín, Colombia

**jose.abadol@amigo.edu.co

***paula.alzatero@amigo.edu.co

This article was received on March 10, 2015, and accepted on August 13, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Abad, J. V., & Alzate, P. A. (2016). Strategies instruction to improve the preparation for English oral exams. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 18(1), 129-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.49592.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article presents the results of an inter-institutional research study that assessed the impact of strategies instruction on students' preparation for and performance in oral exams. Two teacher-researchers at different universities trained 26 students in their respective B1-English-level courses in using language learning strategies. The study included pre- and post-intervention tests and on-line questionnaires after each oral exam. After comparing the test scores and analyzing the questionnaire responses, we arrived at two main conclusions: First, that strategies instruction, especially in combination with evaluation rubrics, promotes students' autonomy and enhances their oral test performance. Second, that students' use of language learning strategies is influenced by instructional variations tied to the relative importance that teachers ascribe to specific aspects of oral communication.

Key words: Language learning strategies, oral assessment, preparation for oral exams, rubrics, strategies instruction.

En este artículo presentamos los resultados de una investigación inter-institucional que evaluó el impacto de la instrucción en estrategias en la preparación para pruebas orales. Dos docentes-investigadores de diferentes universidades capacitaron a 26 estudiantes de nivel B1 en el uso de estrategias de aprendizaje. El estudio incluyó la administración de pruebas antes y después de la intervención y de cuestionarios después de cada prueba. Los datos nos permitieron llegar a dos conclusiones: primero, la instrucción en estrategias, especialmente en combinación con el uso de rúbricas, promueve la autonomía y mejora el desempeño en pruebas orales. Segundo, el uso de estrategias está influenciado por variaciones en la instrucción asociadas a la importancia relativa que cada maestro asigna a aspectos específicos de la comunicación hablada.

Palabras clave: estrategias de aprendizaje en lenguas, evaluación oral, instrucción en estrategias, preparación para pruebas orales, rúbricas.

Introduction

The global imperative to communicate effectively in an international language has gained English a preeminent place in the curriculum across the different levels of education in Colombia. This privileged position of English in Colombian schools is what The National Law of Bilingualism (República de Colombia, 2013) and a recent succession of language policies (Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN], 2006, 2014) dictate. The continual changes these policies have undergone over the last decade have led some local academics to question whether it is possible to effectively implement them (Peláez, Roldán, & Usma, 2014; Usma, 2009). However, since the onset of the National Bilingual Program 2004-2019 (MEN, 2006) to its reformulation as the National Plan of English 2015-2025: Colombia Very Well (MEN, 2014),1 language policy in Colombia has been consistent in at least two aspects: First, that Colombian professionals need to achieve high levels of English proficiency;2 second, that they need to certify those levels of competence through standardized tests.3

Despite the ambitious goals set by the national government, inconsistencies between the teaching and the evaluation of English are the order of the day in Colombia. In a Phase-1 exploratory study, Restrepo and Medina (2014) observed that the results students obtain in English oral exams are usually not in proportion to the efforts they make to prepare for them. Furthermore, many college students study only for passing the exams, but they fail to understand, retain, and transfer linguistic knowledge. As a result, these students' learning gaps show up in course examinations that seek to evaluate their overall communicative competence (Bachman & Palmer, 1996; Canale & Swain, 1980).

Students' difficulties to demonstrate their English competence on school examinations largely occur as a result of ignoring or misusing language learning strategies (Restrepo & Medina, 2014). This deficiency could in turn be linked to the teachers' lack of knowledge or initiative to instruct students on how to use learning strategies to prepare for their evaluations, a lesson which educators often overlook because they neither see the need to teach it nor consider it a part of their teaching role. Aware of the need to find solutions to this problem, researchers from three English teaching programs in Medellín, Colombia, decided to conduct this project in search of a context-appropriate manner to help students improve their preparation for and performance in English oral evaluations.

Literature Review

Types and Forms of Evaluation

In language teaching some differences have been established between evaluation, assessment, and testing. Evaluation serves as an umbrella term that encompasses the application of different means and procedures to judge student achievement, teaching effectiveness, and curriculum appropriateness (Brown & Abeywickrama, 2010). Assessment involves the continuous collection of information about students' learning to inform decisions conducive to the improvement of teaching and curriculum. Finally, testing is a mechanism used to measure students' level of achievement as regards the development of language skills or the appropriation of new knowledge (Arias, Maturana, & Restrepo, 2012; Brown & Abeywickrama, 2010).

Evaluation activities can be classified into different types and forms. There are two main types of evaluation. Once specific moments of learning and teaching have taken place, summative evaluations are administered to verify students' partial or total achievement of specific learning goals (Hadji, 1997). Formative evaluation, on the other hand, entails an ongoing gathering of information about students' learning that teachers can use to inform and adjust their course planning (Council of Europe, 2001). Formative evaluation encompasses all continuous evaluation that teachers integrate into a course sequence in order to remedy students' difficulties, strengthen their learning, and prepare them for summative examinations that will require them to display their language abilities (Arias et al., 2012). Evaluation is also classified into two forms. Traditional evaluation entails a significant degree of teacher control over the expected student answers whereas alternative evaluation involves more freedom of production in this regard (Arias & Maturana, 2005; Maturana, Restrepo, & Ferreira, 2009).

Language Learning Strategies

Research in the field of language learning strategies formally started out with Rubin's (1975) work. She observed that good learners communicate and learn through the target language, seek opportunities to practice it whenever possible, develop strategies to overcome interactional inhibitions, make informed guesses regarding unknown language uses, pay attention to both meaning and form, and monitor their speech and others'. She proposed an initial classification that includes direct and indirect strategies. Although the strategies she described continue to be included as some of the most used by effective language learners, much has been researched, questioned, discussed, and adjusted since her seminal study appeared.

Later research work focused on defining and classifying learning strategies. In her earlier work, Oxford (1990, 1994) defined learning strategies as behaviors, actions, steps, or techniques that students intentionally use to improve their progress in developing their language skills. Chamot and O'Malley (1990, 1994), who conducted studies parallel to Oxford's, concluded that students use strategies to regulate their emotional disposition towards learning and to select, acquire, organize, integrate, and retrieve linguistic knowledge.

Both proponents (Chamot & O'Malley, 1990, 1994; Cohen & Weaver, 2006; Griffiths, 2004, 2007; Oxford, 1990, 1994, 2011; Wenden & Rubin, 1991) and critics (Coyle & Valcárcel, 2002; Ellis, 1994; Macaro, 2006) of the language learning strategies theory have acknowledged the difficulty in providing not only a clear definition but also a broadly accepted classification. However, according to Cohen and Weaver (2006), a certain degree of consensus has been achieved in regard to specific characteristics of the learning strategies. First, they are considered to be part of a larger set of learner strategies that also include use strategies. Second, learning strategies are purposely used by students to achieve specific learning goals, which vary in their immediacy and complexity. Ultimately, however, strategies are aimed at helping students develop their communicative competence in the second language. Third, students' selection and use of strategies largely depend on personal factors such as age, gender, learning style, and motivation; and on external factors such as linguistic task, skill focus, target language, and educational and cultural contexts. Fourth, strategies are not used in isolation but as part of clusters. Finally, whether simultaneously or in sequence, the way in which strategies are coordinated and organized, although influenced by external factors, is always a decision of the learner (Cohen & Weaver, 2006).

Starting with the general notion of learner strategies, Cohen and Weaver (2006) proposed various types of classification. Learner strategies can be classified depending on the language skills they favor, whether they are productive (writing and speaking) or receptive (reading and listening). Nonetheless, there are general skill-related strategies, such as vocabulary, grammar, or translation strategies, which cut across the different skills. In addition, learner strategies can be classified into use or learning strategies depending on the learner's goal. Use strategies include retrieval, rehearsal, communication, and cover strategies. Learning strategies, on the other hand, have been traditionally classified based on function into cognitive, metacognitive, social, and affective strategies (Chamot & O'Malley, 1990, 1994; Oxford, 1990).

Learners employ cognitive strategies to manipulate information in order to facilitate its learning. Thus, cognitive strategies are directly tied to the specific tasks learners want to complete and to the learning objectives they want to achieve. Therefore, cognitive strategies refer to the steps learners take to solve problems that require the direct analysis, synthesis, and reconfiguration of new learning material (Palincsar & Brown, 1984; Wenden & Rubin, 1991).

Metacognitive strategies (Chamot & O'Malley, 1990, 1994; Cohen & Weaver, 2006; Diaz, 2015; Klimenko & Álvarez, 2009; Oxford, 1990, 1994, 2011) allow students to “step back” and manage their language learning through a continuous cycle that involves planning, monitoring, and evaluating what they learn and how they go about learning it. They focus on the before, during, and after of any learning task, which could be as simple as writing a paragraph and as complex as developing their overall language competence.

According to Cohen (2011), social strategies allow learners to interact with other speakers, such as classmates and teachers, to facilitate the completion of a task and the learning process in general. Affective strategies, on the other hand, help students regulate their emotions, motivation, and attitudes towards the task at hand. They also help reduce anxiety and provide encouragement (Cohen, 2011).

In line with the strategies' classification described above, we conceive strategies as thoughts and actions purposely employed by learners to manage and self-direct their learning. Language learning strategies allow students to regulate their emotional dispositions and social interactions around learning, and to apply specific cognitive and metacognitive mechanisms in response to specific learning tasks. Nevertheless, strategies are ultimately aimed at supporting the development of students' communicative competence.

Taking into consideration the educational context of our country, the revision of the literature in the field, and the results obtained in a previous project, we decided to embark on this study to assess (a) the impact of strategies instruction on the degree of students' strategy use in preparing for oral exams and (b) the effectiveness of students' strategy use on their evaluation performance. Finally, we decided to focus on oral tasks because they serve as immediate and accurate indicators of students' actual linguistic competence and because of the cognitive, affective, cultural, and interactional abilities that students must employ to successfully complete such tasks.

Method

This study subscribes to the qualitative research paradigm, which aims to go into detail about how human beings experiment and perceive social phenomena as they occur. From a constructivist-interpretivist perspective, researchers appreciate the point of view of the participants regarding the object of investigation and recognize the impact that a research study may have upon their experiences and lives (González Monteagudo, 2000; Hernández, 1997; Ortiz, 2000).

As an educational action research, the study involved a process through which teacher-researchers sought not only to understand some issues that affect their teaching practice, particularly as regards evaluation, but also to engage in specific actions directed towards the improvement of student learning within their own school communities. Based upon the findings of a Phase-1 descriptive study, this particular project specifically involved a pedagogical intervention that aimed to improve students' strategy use to prepare for their oral evaluations.

We believe, notwithstanding, that qualitative and quantitative measures used for the data collection and analysis are not competing but rather complementary so long as the integrity of the participants is not compromised. For this study in particular, although we did not apply any form of probability sampling, we did collect and analyze quantitative data to enrich the understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. Therefore, from a methodological perspective, the study approaches what Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, and Turner (2007) have denominated a “QUAL + quan research.”

Participants

Participants included two groups of 12 and 14 English-teaching students from two private universities in Medellín, Colombia, and their respective instructors. They were part of the B1-English level4 courses in their corresponding undergraduate programs. Students from both institutions came from a middle-class socio economic background. There were 17 females and nine males, both of them from ages 18 to 25.

Procedures

Sampling

Although quantitative data were used in this study for triangulation purposes, the research team chose participants not through probability but through deliberate sampling (Lankshear & Knobel, 2004). We5 collected data from only two groups of students for philosophical, technical, practical, and ethical reasons. In the first place, as a research team, we wanted to gain insight on the impact of strategies instruction by means of studying our own classes rather than other teachers'. In addition, from the inception of the study we decided that data would be collected in intermediate (B1) English courses, because prior studies (Chamot, Barnhardt, Beard, Carbonaro, & Robbins, 1993; Cohen, Weaver, & Li, 1996) have shown that students at this level of competence benefit more from strategies instruction than students at any other proficiency level. Nevertheless, due to course allocation processes, only two members of the team were assigned intermediate level courses during the data collection period, so we ended up working with only those two classes. Finally, due to ethical considerations, these two teachers provided strategies instruction and administered the pre- and post- tests to all the students in both classes, but as a team we used only the data supplied by the students who signed the consent forms, thus following what Bell (2010) has called “opportunity sampling” (p. 150).

Data Collection

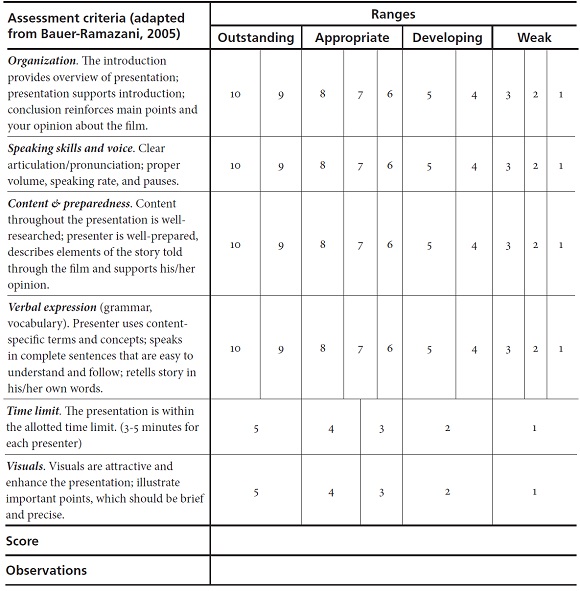

The collection of the data involved a strategy instruction intervention, pre- and post-tests (diagnosis formative assessment and final summative assessment), and the application of on-line questionnaires after each evaluation. Table 1 illustrates the steps, objectives, and instruments used.

In order to guarantee the reliability and internal validity of data-collection instruments (rubric and questionnaires), the researchers who participated in the study designed them as a group and later submitted them to the evaluation of external researchers and test designers. To ensure the validity of the oral exams scoring, a researcher different from the course instructors served as co-evaluator for both the diagnosis and the summative exams. Students' scores in the oral exams were reached through a consensus between the course instructor and the external evaluator.

Intervention

With the strategies instruction workshop, the two instructors trained students to recognize and use learning strategies to prepare for their oral exams. The intervention, which was applied only once, lasted four hours and was divided into two sessions of two hours each. The instructors conducted the workshop separately with their respective classes.

In line with the recommendations made by Cohen (2011) and Chamot (2005), both teachers delivered the strategies instruction workshop through the following stages: (a) activation of previous knowledge, (b) definition of learning strategies, (c) classification of learning strategies, (d) teacher modeling of learning strategies, (e) students practice with learning strategies, and (f) students' demonstration of strategy application. However, the instructors were allowed to modify the order of the previous stages and the way in which they conducted them in accordance with their teaching style and with the institutional principles that guide instruction at each university.

The workshop was specifically geared towards helping students prepare for their course final summative evaluation, which consisted of an oral review of a movie of their choice. Therefore, taking into consideration the test-specific requirements, both teachers incorporated as part of the intervention a general analysis of the results obtained by their students in the previous diagnosis evaluation, of the speaking-oriented strategies included in both questionnaires, and of the common rubric and the way in which the learning strategies could help students prepare to meet the evaluation criteria established in it.

Data Analysis

During this stage, three data sources were considered: (a) the answers to the closed questions of the questionnaire that indicated students' degree of recognition, selection, and use of learning strategies before and after the intervention;6 (b) the results obtained by students on both oral exams; and (c) the answers provided for the open-ended questions in the last part of the questionnaires in which students were required to describe and evaluate the strategies they used to prepare for each oral evaluation.

An external advisor guided us through the process of analysis and interpretation of the quantitative data obtained from both the first section of the questionnaires and the test scores. For the analysis of the test results, we first calculated the total scores and the scores for each of the rubric domains within a range of 10. Then, to determine the progress made after the intervention, we calculated the means and then established the difference between the values obtained for both the diagnosis and the summative exams. Finally, we identified general trends in the overall results and specific discrepancies between the results shown by the two groups.

Qualitative data from the second part of both questionnaires were analyzed following an inductive-deductive process of categorization, grouping, and interpretation through NVivo® software. Researcher triangulation was employed through three stages of codification (by individual researchers, by codification sub-teams, and by the whole research group) in order to validate the categorization of the results. Finally, the research team validated the interpretations with one another.

Results

Strategies Selection and Use

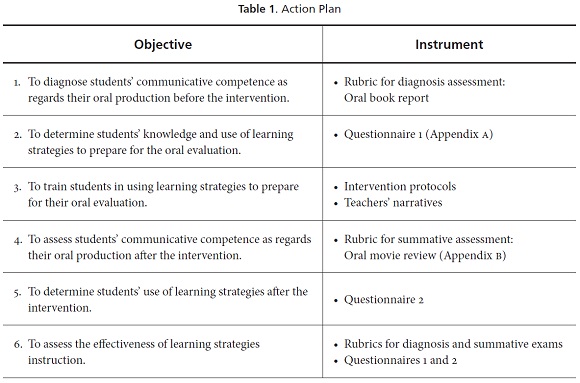

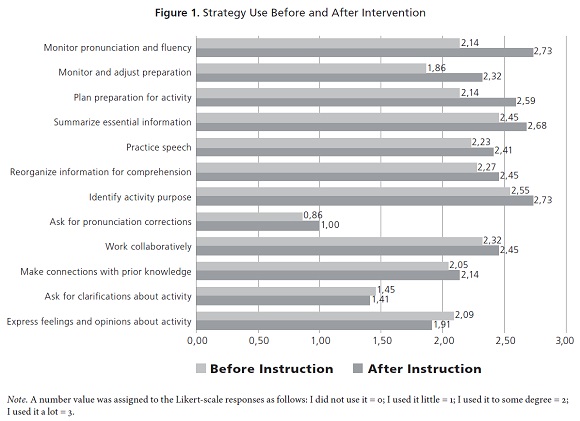

In order to assess the impact of strategies instruction on the degree of students' strategy use, we compared the results of the closed-response section of the questionnaires that were administered after each evaluation. Although 26 students participated in the study, only 22 students answered the questionnaires. Figure 1 shows the average use of strategy before and after the intervention. Strategies are organized from top to bottom according to the gain they experienced in terms of student use after the intervention. Out of the 12 strategies presented in the questionnaires, 10 had an increase in the proportion of student use, and only two of them had a decrease. The strategies that had the most significant growth were monitoring pronunciation and fluency, monitoring and adjusting the preparation for the activity, and planning the preparation for the activity. The two strategies that experienced a decrease in student use were asking for clarifications and expressing feelings and opinions.

Before the intervention, the strategies that students used the most were identifying the task's purpose and summarizing the essential information; in contrast, the strategies that students used the least were asking the teacher for clarification about the evaluation and asking for pronunciation corrections. After the intervention, the strategies that students used the most were identifying the task's purpose, monitoring pronunciation and fluency, summarizing essential information, and planning the preparation for the activity whereas the strategies that students used the least continued to be asking the teacher for clarification about the activity and asking for corrections on their pronunciation. Figure 2 shows the growth in strategy use, which was established after comparing the use of each strategy before and after the intervention.

In relation to the most used strategies, the qualitative data showed that the use of rubrics played a part in helping students identify the purpose of the activity. For instance, when asked about the most effective strategy he had used to prepare for these tests, one student answered:

I am familiar with this type of evaluation (oral presentation), and I know by experience that it is very important to take the time to read the rubric, to analyze it, and to identify what is the most relevant (for that evaluation) and what could also be a challenge when presenting. (Student 16)7

In addition, it is worth noting that metacognitive strategies that involved planning and adjusting the preparation for the activity were not only among the ones most used but also among the ones whose use grew the most. They were followed by cognitive strategies such as summarizing and reorganizing the information and practicing the speech. Students recurrently used these strategies before and after the intervention. In contrast, social and affective strategies that involved, for instance, expressing opinions and asking for clarifications and corrections were not only the least used but the ones whose use decreased the most.

These quantitative data from the questionnaires are consistent with the results obtained in the analysis of the open responses that students gave as regards the strategies they used. The analysis done through NVivo revealed that in terms of the amount of information that students provided regarding strategies, 50% of the references corresponded to cognitive strategies, 25% to metacognitive strategies, 15% to social strategies, and only 10% to affective strategies.

The results shown by the questionnaires indicate that strategies instruction increased the students' use of learning strategies. Results also show that strategies instruction especially favored the purposeful use of metacognitive strategies, even though cognitive strategies were the ones most consistently used across all stages of the study. This evidence suggests that students in general were somewhat familiar with cognitive strategies, even before the instruction they received, which is not surprising given that cognitive strategies are the most widely known in these students' academic context. Instruction, however, proved to be fundamental in getting learners acquainted with metacognitive strategies and with the way in which they could use them to better the effectiveness of their overall test preparation. This effect of strategies instruction became clear in the significant growth in the use of metacognitive strategies that students exhibited during the second evaluation.

Strategies Impact on Students' Preparation for and Performance in Oral Exams

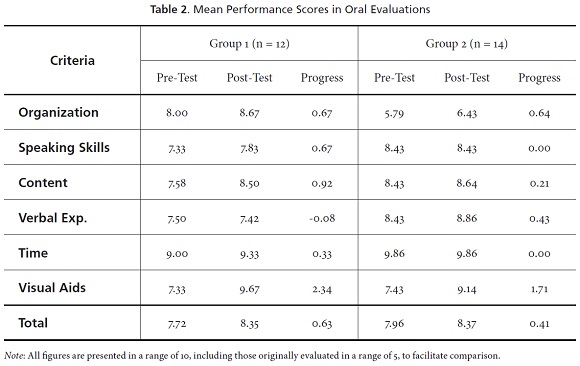

To assess the effectiveness of students' strategy use on their evaluation performance, we compared the results obtained by both groups in the pre- and post- intervention tests, as shown in Table 2.

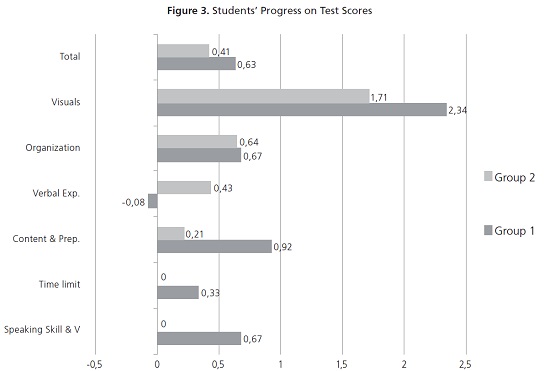

These results show that, on average, students from both groups improved on their total test scores after they received strategies instruction. Out of the 26 participants, six of them decreased their test scores whereas 19 increased them. Of the 12 students from Group 1, 11 obtained a higher score in the final test, and only one of them (the lowest-performing student) obtained a lower score than she had gotten on the first test. On the other hand, of the 14 students from Group 2, eight improved their test scores and six lowered them. Nonetheless, students from the Group 2 had obtained very high scores in linguistic aspects such as speaking skills, content preparedness, and verbal expression on the diagnosis test, and most of them either kept or improved those scores on the second exam. Figure 3 shows the progress of the test scores for both groups.

Here it is important to clarify the domains speaking skills and verbal expression as used in the evaluation rubric (Appendix B). Speaking skills were defined as the ability of students to pronounce clearly, to speak at an adequate pace, to use proper volume, and to make adequate use of pauses during their speech. On the other hand, verbal expression referred to the students' ability to appropriately use content-specific terms within grammatically correct structures to retell and analyze the stories they had selected for their presentation.

Although both groups of students had an increase on their test scores, their improvement was not homogeneous. On the one hand, students from Group 1 increased in use of visuals, content and preparedness, organization, and speaking skills, but they decreased in their verbal expression. In other words, they improved in all the criteria set for the evaluation except for their verbal expression, which actually decreased. On the other hand, students from Group 2 increased in their use of visual aids, organization, verbal expression, and content and preparedness, but they had no improvement on either their use of time or their speaking skills, albeit they had the highest scores for speaking skills from the first evaluation, and they kept them that way. Although these latter students improved the quality of their discourse and the form of their presentation, their speaking skills stayed the same.

Variations in the results obtained by both groups seem to be in alignment with the emphasis that teachers put on certain aspects of the oral evaluation during the instruction, as expressed by them in post-data collection discussions.

The teacher of Group 1 perceived that many students, when preparing for oral exams, had the tendency to focus excessively on organizational aspects of their presentation, often because they were afraid of making mistakes. As a result, he said, many students wound up memorizing their speech from a script and later reciting it during the presentation, which ultimately affected the overall flow of communication. Therefore, he instructed students to focus on understanding and communicating ideas (preparedness), even if that meant making a few grammar or vocabulary mistakes. He also highlighted the importance of adequately using visuals and organizing the discourse within a logical structure to increase clarity and facilitate the audience's comprehension.

In contrast, the teacher of Group 2 declared that she gave her instruction from a holistic perspective of what the communicative competence is. Nonetheless, in the first assessment she noticed that although her students showed an overall good level of language proficiency, they had difficulties in the use of discourse as refers to the appropriation of the type of text that was required from them. Some of them, for instance, retold a story in their own words, but they failed to analyze the story's basic literary elements and to follow the structure of an oral presentation, as the task instructions required. After asking students to pay closer attention to the formal aspects of their discourse, she observed that they were indeed ameliorated for the second exam, particularly as regards students' appropriation of the text type.

Evidently, teachers favored some aspects of oral communication over others in their instruction. Although such emphasis may have come from particular teaching styles, it was mostly a conscious attempt from the teachers to address the communication problems and learning needs that they had observed in their specific groups of students. This relative importance that teachers ascribed to specific aspects of the oral evaluation appeared to have a direct effect on the way students prepared for the second exam.

Discussion

Strategies Selection and Use

With respect to the use of strategies to prepare for English oral exams, results suggest that the clearer the instruction provided by teachers regarding the evaluation activity, the less will students have to resort to them for additional clarification. Furthermore, in line with other studies on assessment (Jonsson & Svingby, 2007; Panadero & Jonsson, 2013; Picón Jácome, 2013), this research shows that sharing rubrics with students in advance may help them identify the purpose of the evaluation activity and may give them a heightened sense of control over their test preparation. To attain these benefits, however, rubrics should clearly describe the learning objectives to be achieved, the procedural requirements to be met, and the evaluation criteria upon which performance will be assessed.

Results also seem to indicate that direct strategies instruction increases students' awareness of learning strategies and their subsequent use. This holds true particularly for metacognitive strategies, which, as opposed to most cognitive strategies, call for direct instruction so that students can really grasp what they are and how they can be used to enhance learning (Cohen & Weaver, 2006). Moreover, when strategies instruction is specifically incorporated into a language course to assist students in better preparing for their oral exams, it appears to increase the students' use of metacognitive strategies such as planning, monitoring, and adjusting their test preparation, which are pivotal for students to have a successful test performance.

In conclusion, students' selection and use of strategies to prepare for an oral evaluation seems to be directly affected by the quality of the instruction they receive from teachers. Using carefully designed rubrics and sharing them with students before the evaluation enhance their comprehension of what is expected of them and how they can achieve it, thus increasing their sense of autonomy. We believe that when rubrics are used in tandem with strategies instruction as part of a comprehensive instructional system, students are empowered with a greater sense of control over their learning, and they can prepare more effectively to increase their test performance.

Strategies Impact on Students' Preparation for and Performance in Oral Exams

Results indicate, nonetheless, that even though strategies instruction does contribute to improve students' preparation for and subsequent performance in English oral exams, instructional variations derived from teachers' focus on specific aspects of the evaluation also affect students' strategy use.

Previous work in the field of language learning strategies (Cohen & Weaver, 2006; Griffiths, 2007; Oxford, 1994, 2011; Tragant & Victori, 2012) has already pointed out that the selection and use of learning strategies depend on a number of factors, such as age, gender, learning style, and type of activity. The results of this study also suggest that the perceived importance of specific aspects of the evaluation on the part of the teacher might be connected to the strategies that students use in preparing for it. This perceived importance of aspects such as verbal expression, language skills, organization, and preparedness is directly linked to the value that teachers assign to them during instruction.

Regardless of how prescriptive strategies instruction may sometimes appear, it is ultimately the teachers' responsibility to gear it towards meeting the language learning needs of their students. However, teachers must bear in mind that the relative priority they give to some aspects of language might influence their students' choice of strategies and, ultimately, their overall language learning process.

*This article presents some of the final results of an inter-institutional study titled, Estrategias de Aprendizaje que Favorecen la Preparación del Estudiante para la Evaluación de su Desempeño Respecto a su Competencia Comunicativa en Inglés (code number 38169). This study was collectively sponsored by Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó, Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, and Universidad de Antioquia, and involved the participation of researchers from the language teaching programs of these three institutions. Also, the preliminary findings of this study were presented by the authors during the VI Coloquio Internacional sobre Investigación en Lenguas Extranjeras that took place in September of 2014 at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá.

1While we were preparing the final version of this article, the new government of President Santos nullified the National Plan of English 2015-2025, thus rendering it the shortest-lived language policy in Colombia's history to date. A new language policy to replace it had yet to be formulated.

2Professionals across different areas of study must reach a B1 level of proficiency and English teachers must reach a C1 level according to the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2001).

3All undergraduate students must demonstrate these levels of competence in the Saber-pro examinations, which are a mandatory requirement for college graduation. In addition, public school teachers are expected to take the Annual Diagnosis Test to certify their English proficiency. Both tests are administered by the National Institute for the Evaluation of Education (ICFES).

4According to the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2001).

5The pronoun we is used throughout the article to refer to the authors and, through them, to the entire research team who participated in the project. The team was made up of nine people, including teachers, advisors, and assistant students who performed various roles over the course of the study. The term instructors, however, refers exclusively to the two teacher-researchers who collected the data and supplied the strategy instruction to their respective classes. It is worth pointing out that of these two instructors, only one (José Abad) co-authored this article.

6The set of strategies included in this instrument was pre-selected by the research team based on an analysis of Oxford's (1989) strategy inventory.

7The original comments in Spanish were translated for the purpose of publication.

References

Arias, C. I., & Maturana, L. M. (2005). Evaluación en lenguas extranjeras: discursos y prácticas [Evaluation in foreign languages: Discourses and practices]. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 10(16), 63-91. [ Links ]

Arias, C. I., Maturana, L. M., & Restrepo, M. I. (2012). Evaluación de los aprendizajes en lenguas extranjeras: hacia prácticas justas y democráticas [Evaluation in foreign language learning: Towards fair and democratic practices]. Lenguaje, 40(1), 99-126. [ Links ]

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice: Designing and developing useful language tests. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bauer-Ramazani, C. (2005). Presentation rubric [Assessment rubric]. Retrieved from http://academics.smcvt.edu/cbauer-ramazani/IEP/SPKG/present_rubric2.htm. [ Links ]

Bell, J. (2010). Doing your research project: A guide for first-time researchers in education, health and social science. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Brown, H. D., & Abeywickrama, P. (2010). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices (2nd ed.). White Plains, NY: Pearson. [ Links ]

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1-47. [ Links ]

Chamot, A. U. (2005). Language learning strategy instruction: Current issues and research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 25, 112-130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0267190505000061. [ Links ]

Chamot, A. U., & O'Malley, J. M. (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Chamot, A. U., & O'Malley, J. M. (1994). The CALLA handbook: How to implement the Cognitive Academic Language Learning Approach. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Chamot, A. U., Barnhardt, S., Beard, P., Carbonaro, G., & Robbins, J. (1993). Methods for teaching learning strategies in the foreign language classroom and assessment of language skills for instruction: Final report. Washington, DC: Georgetown University. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED365157) [ Links ]

Cohen, A. D. (2011). Second language learner strategies. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning: Vol. II (681-698). New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. D., & Weaver, S. J. (2006). Styles-and-strategies-based instruction: A teachers' guide. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. D., Weaver, S. J., & Li, T. (1996). The impact of strategy-based instruction on speaking a foreign language. Minneapolis, MN: Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition. [ Links ]

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Strasbourg, FR: Author. Retrieved from http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Source/Framework_en.pdf. [ Links ]

Coyle, Y., & Valcárcel, M. (2002). Children's learning strategies in the primary FL classroom. CAUCE, Revista de filología y su didáctica, 25, 423-458. [ Links ]

Diaz, I. (2015). Training in metacognitive strategies for students' vocabulary improvement by using learning journals. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 17(1), 87-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n1.41632. [ Links ]

Ellis, R. (1994). Understanding second language acquisition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

González Monteagudo, J. (2000). El paradigma interpretativo en la investigación social y educativa: nuevas respuestas para viejos interrogantes. [The interpretivist paradigm in social and educational research: New answers for old questions]. Cuestiones Pedagógicas: Revista de Ciencias de la Educación, 15, 227-246. Retrieved from http://institucional.us.es/revistas/cuestiones/15/art_16.pdf. [ Links ]

Griffiths, C. (2004). Language learning strategies: Theory and research. Retrieved from http://www.crie.org.nz/research-papers/c_griffiths_op1.pdf. [ Links ]

Griffiths, C. (2007). Language learning strategies: Students' and teachers' perceptions. ELT Journal, 61(2), 91-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccm001. [ Links ]

Hadji, C. (1997). L'évaluation démystifiée [Evaluation demystified]. Paris, FR: ESF Editeur. [ Links ]

Hernández, G. (1997). Caracterización del paradigma constructivista [Characterization of the constructivist paradigm]. Retrieved from https://comenio.files.word press.com/2007/10/paradigma_psicogenetico.pdf. [ Links ]

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112-133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1558689806298224. [ Links ]

Jonsson, A., & Svingby, G. (2007). The use of scoring rubrics: Reliability, validity and educational consequences. Educational Research Review, 2(2), 130-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2007.05.002. [ Links ]

Klimenko, O., & Álvarez, J. L. (2009). Aprendizaje autorregulado y motivación escolar [Self-regulated learning and school motivation]. Pensando Psicología, 5(9), 21-35. [ Links ]

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2004). A handbook for teacher research: From design to implementation. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Macaro, E. (2006). Strategies for language learning and for language use: Revising the theoretical framework. Modern Language Journal, 90(3), 320-337. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2006.00425.x. [ Links ]

Maturana, L. M., Restrepo, M. I., & Ferreira, M. P. (2009). Módulo-guía en evaluación de los aprendizajes en lenguas extranjeras [Guidelines in evaluation of foreign languages]. Medellín, CO: Universidad de Antioquia. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (2006). Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: inglés. Serie Guías No. 22 [Basic standards for foreign language competences: English]. Bogotá, CO: Author. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/cvn/1665/article-115174.html. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (2014). Colombia Very Well: Programa Nacional de Inglés, 2015-2025. Documento de Socialización. [National English Program, 2015-2025. Presentation Document]. Bogotá, CO: Author. Retrieved from http://www.colombiaaprende.edu.co/html/micrositios/1752/articles-343287_recurso_1.pdf. [ Links ]

NVivo (Version 10). [Computer software]. Burlington, MA: QSR International. [ Links ]

Ortiz, J. R. (2000). Paradigmas de la investigación [Research paradigms]. UNAdocumenta, 14(1), 42-48. Retrieved from http://postgrado.una.edu.ve/filosofia/paginas/ortizunadoc.pdf. [ Links ]

Oxford, R. L. (1989). Strategy inventory for language learning. New York, NY: Newbury House. Retrieved from http://www.santurtzieus.com/gela_irekia/materialak/laguntza/nolaikasi/evaluacion_estrategias.htm. [ Links ]

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle. [ Links ]

Oxford, R. L. (1994). Language learning strategies: An update. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED376707) [ Links ]

Oxford, R. L. (2011). Teaching and researching language learning strategies. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Palincsar, A. S., & Brown, A. L. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring activities. Cognition and Instruction, 1(2), 117-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci0102_1. [ Links ]

Panadero, E., & Jonsson, A. (2013). The use of scoring rubrics for formative assessment purposes revisited: A review. Educational Research Review, 9, 129-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002. [ Links ]

Peláez, O., Roldán, A., & Usma, J. (2014, September). The national English program in Colombia: Plans, realities, delusions, and challenges. Plenary session presented at the Sixth Academic Sessions: Participating and Creating, Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó, Medellín, Colombia. [ Links ]

Picón Jácome, E. (2013). La rúbrica y la justicia en la evaluación [The role of rubrics in fair assessment practices]. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 18(3), 1-16. [ Links ]

República de Colombia. (2013, July). Ley de Bilingüismo (Ley No 1651) [Law of bilingualism]. Retrieved from http://wsp.presidencia.gov.co/Normativa/Leyes/Documents/2013/LEY%201651%20DEL%2012%20DE%20JULIO%20DE%202013.pdf. [ Links ]

Restrepo, M. I., & Medina, M. I. (2014). Factores y estrategias que inciden en la preparación para la evaluación en inglés en la Funlam [Factors and strategies that influence preparation for the evaluation in English at Funlam]. In J. D. Ruíz Roldán & C. Orrego Moscoso (Eds.), La investigación, un compromiso con la sociedad: memorias del Encuentro Nacional de Investigación Funlam 2014 (pp. 303-315). Retrieved from http://www.funlam.edu.co/uploads/centroinvestigaciones/129_LA_INVESTIGACION_Un_compromiso_con_la_sociedad_2014.pdf. [ Links ]

Rubin, J. (1975). What the "good language learner" can teach us. TESOL Quarterly, 9(1), 41-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3586011. [ Links ]

Tragant, E., & Victori, M. (2012). Language learning strategies, course grades, and age in EFL secondary school learners. Barcelona, ES: Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. [ Links ]

Usma, J. A. (2009). Education and language policy in Colombia: Exploring processes of inclusion, exclusion, and stratification in times of global reform. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 11(1), 123-141. [ Links ]

Wenden, A., & Rubin, J. (Eds). (1991). Learner strategies in language learning. New York, NY: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

About the Authors

José Vicente Abad works as associate professor at Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó (Medellín, Colombia). A member of EILEX Research Group, he coordinates both the research line in evaluation and the Semillero en Evaluación de Lenguas Extranjeras (Student Research Group in Language Evaluation). His research interests include language evaluation and teacher professional development.

Paula Andrea Alzate is finishing her BA in English Teaching at Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó (Medellín, Colombia). She works at The Columbus School and is also a member of the Semillero en Evaluación de Lenguas Extranjeras. Her interests include language evaluation and research in education.

Researchers in the field of language teaching from Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó, Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, and Universidad de Antioquia participated in the project Learning Strategies that Favor Students' Preparation for English Oral Exams. To collect data for this study, we ask that you please answer the following questionnaire.

1. General Information

Complete the requested information.

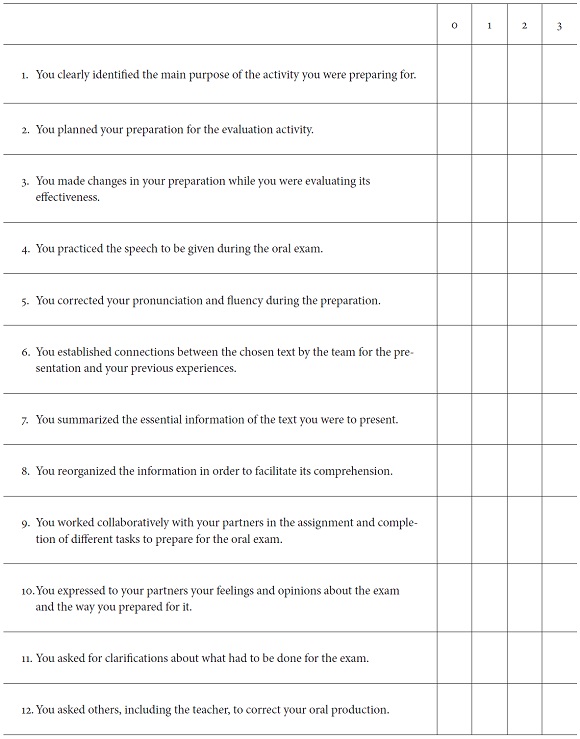

2. Strategies

Language learning strategies are defined as behaviors, actions, steps or techniques that students use to improve their progress in developing their language skills (Oxford, 1990). This section is related to the learning strategies you could use during your preparation for English oral exams.

Part A: Scale

Indicate if you used the following preparation activities. If so, tell to what extent you did it by selecting the option you consider the most appropriate in each case.*

0 = I did not use it; 1 = I used it a little; 2 = I somewhat used it; 3 = I used it a lot.

Part B: Questions

Answer the following questions, providing all the information you consider to be relevant.

- How did you prepare for the exam? Describe the process in detail, including those strategies that were not described in the previous section.

- How was the team work carried out? Describe the difficulties and achievements you had during the preparation for the exam.

- How did you handle the feelings generated by the exam during your preparation?

- Of the strategies you used to prepare for the exam, which were the most effective? Why?

- Of the strategies you used to prepare for the exam, which were the least effective? Why?

- If you could take the exam again, which changes would you make in your preparation in order to improve your performance during the exam?

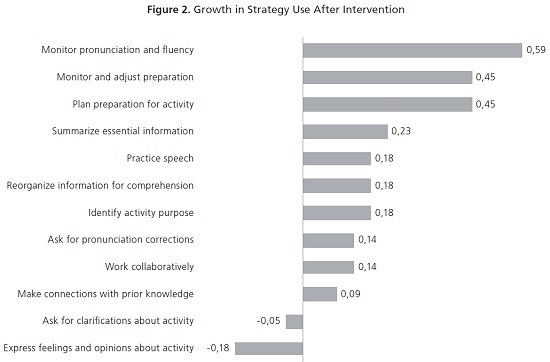

Appendix B: Rubric for Summative Evaluation: Movie Review

Instruction. In pairs you're going to choose a film of your interest and do an oral presentation about it. For the oral presentation take into account the following:

- Describe its main elements: characters (2-3), plot, setting, conflict, and resolution

- Make sure your presentation has an introduction, development, and conclusion and connect them

- Express your point of view about the film

You're going to be assessed based on the following rubric. Assessment will be individual.