Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.19 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2017

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.53955

http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.53955

Language Learning Shifts and Attitudes Towards Language Learning in an Online Tandem Program for Beginner Writers

Cambios lingüísticos y actitudes hacia el aprendizaje de lenguas en un programa virtual tándem para escritores principiantes

Constanza Tolosa*

The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Claudia Lucía Ordóñez**

Diana Carolina Guevara***

Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

*c.tolosa@auckland.ac.nz

**clordonezo@unal.edu.co

***dcguevaran@unal.edu.co

This article was received on November 3, 2015, and accepted on July 22, 2016.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Tolosa, C., Ordóñez, C. L., & Guevara, D. C. (2017). Language learning shifts and attitudes towards language learning in an online tandem program for beginner writers. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 19(1), 105-118. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.53955.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

We present findings of a project that investigated the potential of an online tandem program to enhance the foreign language learning of two groups of school-aged beginner learners, one learning English in Colombia and the other learning Spanish in New Zealand. We assessed the impact of the project on students' learning with a free writing activity done as pretest and posttest and used a semi-structured interview to explore their attitudes towards language learning and their perceived development of their native language. Data analysis indicated statistically significant gains in foreign language writing and positive attitudinal changes toward foreign and native language learning.

Key words: Computer mediated communication, foreign language writing, language learning shifts, tandem language learning.

Presentamos los resultados de un proyecto que investigó el potencial de un programa de comunicación virtual tándem para mejorar el aprendizaje de lengua extranjera de dos grupos de adolescentes jóvenes principiantes, uno en Colombia en el aprendizaje de inglés y otro en Nueva Zelanda en el aprendizaje de español. Evaluamos escritura libre como pretest y postest para determinar el impacto del proyecto en el aprendizaje de cada lengua, y con una entrevista semiestructurada exploramos las actitudes de los estudiantes hacia sus clases de lenguas y su percepción del desarrollo de su lengua madre. El análisis de los datos arrojó ganancias estadísticamente significativas en la escritura en cada lengua extranjera y cambios positivos en actitudes hacia el aprendizaje de la lengua extranjera y la materna.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje de lenguas en tándem, cambios lingüísticos, comunicación mediada por computador, escritura en lengua extranjera.

Introduction

As a consequence of the vertiginous increase in communication between speakers of different languages worldwide, foreign language learning is not only important today as an academic task but it is a 21st century imperative that provides speakers with access to information and people in the target language. However, in largely monolingual countries like Colombia, learning foreign languages is hampered by lack of contact with speakers of the target language. Language education is increasingly turning to computer mediated communication (CMC) to facilitate contact between learners with native speakers of the languages they are learning. CMC is broadly defined as the way in which telecommunications technologies have combined information technology and computer networks to offer new tools to support teaching and learning (Warschauer, 1997). While implementing these types of activities in foreign language learning environments is increasingly popular, research into the effects of this implementation is just beginning (Dooly & O'Dowd, 2012), with the majority of studies documented within post-secondary contexts (see O'Dowd & Ware, 2009, for a review).

The study reported here aimed to advance our understanding of how CMC, and specifically tandem communication, can support foreign language (FL) learners in developing their beginner language skills by communicating with speakers of the target language in writing. Using a sociocultural view of learning, we present in this article findings of a project that investigated the potential of a reciprocal peer tutoring (i.e., tandem) program to enhance the FL learning of two groups of school-aged beginner learners, one group located in Colombia and the other in New Zealand. The study extends the findings of a previous tandem project documented by the researchers (Tolosa, Ordóñez, & Alfonso, 2015). It is located at the intersection of two bodies of research as identified by Ware and Hellmich (2014): It focuses on learning outcomes and how technology might influence them, and it uses technology as a site for learning where new learning environments "expand semiotic resources and new modes of communication" (p. 141).

Theoretical Background

CMC refers to communication between two parties connected by technological devices. It is also described as a pedagogical tool that enables groups separated in time and space to engage in active production of shared knowledge through exchanges that can be synchronous (in real time) or asynchronous (in deferred time) (Warschauer, 1997). Research on CMC points at advantages over face to face language learning such as meaningful communicative engagement (Lafford & Lafford, 2005), increased motivation (González-Lloret, 2003), particularly towards written production (Kern, 1995), enhanced practice of the target language in a trustful environment, and a more equitable participation between learners (Warschauer, 1997). It has been suggested that written online communication provides an ideal medium for students to benefit from, since it allows greater opportunity to attend to and reflect on the form and content of written communication. In asynchronous online communication students have more time to plan, compose, revise, and edit their texts as well as opportunities to read and reflect on their interlocutors' texts (Warschauer, 2005). In other words, writing online supports writing as a process, as it promotes genuine interaction (Manchón, 2011). This interaction removes the barriers of time and space that characterise remote language learning (Salaberry, 1996), although there is a loss of immediacy as learners have to wait for their peers' response (Andrews & Haythornthwaite, 2007).

One kind of CMC, the one relevant to the present study, is tandem learning between pairs of students from different linguistic backgrounds. The students are learning as a FL the language that the other student of the pair holds as L1. This pairing establishes a tutor-tutee relationship based on the assumption that students will have equal levels of expertise in their respective L1s. This form of tutoring often relies on structured academic activity and has been found to increase language development (Fantuzzo & Ginsburg-Block, 1998). It is also likely to increase student self-confidence and positive attitudes towards the FL (Thurston, Duran, Cunningham, Blanch, & Topping, 2009), as it is based on the principles of autonomy and reciprocity (Brammerts, 1996).

The notion of tandem is underpinned by a sociocultural view of learning as mediated by social interaction with a more knowledgeable other: A person who possesses a better understanding or higher level of ability than the learner; the learning partners then work in what is known as the zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978). In recent years, a broader scope of the zone of proximal development has been adopted that is not restricted to interactions between a learner and a more knowledgeable other but that also includes peer-to-peer interaction and interaction with technology (Lantolf & Thorne, 2006; Warschauer, 2005). This collective scaffolding provides a space in which learners support one another's development by collaboratively taking their linguistic output to a higher level (Lantolf, 2012). Philp, Adams, and Iwashita (2014) explain that increased appreciation of the value of peer-to-peer interactions is supported by both a cognitive perspective (e.g., Long's [1996] interaction hypothesis) and a sociocultural perspective in which learning is "collaborative, in the sense of participants working together toward a common goal . . . a jointly developed process and inherent in participating in interaction" (Philp et al., 2014, p. 3, p. 8). Tandem enhances opportunities for FL learners to practise communication, negotiate meaning, and take on new roles, as Van den Branden (2006) puts it, "by understanding language input and by producing language output, i.e. by interacting with other people in real-life situations through the use of language, the goals that the learner has in mind can be (better) achieved" (p. 4).

Applying these notions to FL writing, peers engage in mutual scaffolding, helping each other to extend their writing abilities. Peer responses provide an authentic sense of audience and may promote writers' autonomy and confidence (Ware & O'Dowd, 2008), as well as develop communicative competence and inspire more learner participation (Hyland, 2003). However, peer-to-peer work may have disadvantages. For instance, Hyland and Hyland (2006) point to limitations in the interactions because learners may lack communication and pragmatic skills, or hold different expectations about the interactions when coming from different cultural groups. Other researchers have questioned the ability of peers to offer support to others who are in the same learning process (Mendonça & Johnson, 1994). Despite these reservations, when the tandem is organized between pairs who have similar language ability in the FL, it provides an opportunity for learners to use their language with a peer who is experiencing the same process and may have fewer inhibitions to use the FL and be more willing to help her/him (Brammerts, 1996).

Researchers have also begun exploring how interactive writing can promote intercultural communication in tandem projects where students communicate with international partners by developing a different set of competences and skills increasingly viewed as important for communicating online in the 21st century (Guth & Helm, 2010). Tandems can be done via email exchanges as was the case in a study that used authentic cultural communicative tasks between senior high school students in both the United Sates and Hong Kong, who described the exchanges as positive and felt that writing their emails was easier and faster and error correction was useful (Greenfield, 2003). In another email tandem, Canga Alonso (2012) analysed three e-mails produced by students at different times for reciprocity and corrections of texts, concluding that the principle of reciprocity holds while corrections varied across time. Reciprocity was also included in a study between advanced exchange students in Japan that communicated with Japanese students who volunteered to interact via a Bulletin Board System (Kitade, 2008). The author concluded that the preparation of written texts increased the collaboration between the pairs and helped students consolidate L2 knowledge.

CMC and tandem studies suggest the potential of interactive writing for promoting online communication skills, arguably introduced by an increasingly networked, interactive world outside the classroom. Interactive writing in online spaces, whether with local or global interlocutors, has been shown to afford language learners the opportunity to hone their understanding and application of the writing process; it may also help them develop cross-cultural understanding.

Participants and Intervention

The project involved a group of 27 eleven-year-old students in a public school in Auckland, New Zealand, learning Spanish as a FL and a class of 30 peers with ages from 11 to 14 learning English as a FL in a public school in Bogotá, Colombia. The students in both sites were beginner learners of the language and were placed in dyads with comparable foreign language levels, based on their performance on a parallel FL diagnostic test, to ensure that they would be able to actively engage in peer tutoring. A number of students were paired into triads to accommodate the higher number of Colombian students. At the end, only data from participants who completed all the tasks -the 27 New Zealand participants and 21 Colombians-were used.

The students participated in reciprocal peer tutoring through asynchronous written interaction in Moodle, sending each other messages on topics chosen by their teachers on the basis of the topics dealt with in their language classes (students' self-descriptions and descriptions of family, hobbies, likes and dislikes, schools and classrooms, lunch boxes, cities, and favourite celebrities). Each participating student received their unique username and password to ensure privacy and security, and the data were only accessible to the students, teachers, and researchers involved in the project.

The teachers carried out the project in the context of their regular classes. They were asked to dedicate one session per week of their normal curriculum to the peer writing project. The session should have ideally taken place with each student at a computer, but this was not possible with the Colombian group due to limitations in the availability of machines. Every week for eight weeks, students sent each other a short message in their FL on the week's designated topic. The peer tutors read the messages in their L1, identified errors, and provided feedback to their tutees. The tutees then considered their tutors' corrections and suggestions and edited the messages, which they resubmitted as final versions to complete the cycle of writing-feedback-rewriting. This process continued until students completed five sets of messages in their L2. The teachers agreed to provide minimal writing support, yet introduced sequentially the types of possible corrections to be done in texts (identify the error, provide the correct answer, provide an explanation, suggest alternative ways of expressing their ideas).

Unfortunately, the process could not be followed perfectly in the Colombian school because it did not have complete resources and the students' work was constantly interrupted by multiple events unrelated to school activities. A major disruption occurred when the posttest data were being collected, which led the Colombian research team to include the last message in Moodle as a part of the posttest.

The Study

The study aimed to assess the impact of the communicative activity on the students' FL learning, on their attitudes towards it, and on their metalinguistic awareness in their L1. The following questions were answered in the study:

- Do young native speakers of Spanish and English engaged in online tandem interaction improve their writing in the FL when they have their texts corrected by peers? If so, what do they improve on?

- Do these young learners report changes in their attitudes towards learning the FL as a result of their participation in the tandem interaction? If so, what changes do they report?

- Do these young learners learn something about their L1 in the interaction by tandem? If so, what do they learn?

A mixed methods design was used with the following data collection and analysis methods:

-

To answer the first question about what students learned in FL writing, we used quantitative data from a pretest/posttest free-writing FL task and qualitative data from a semi-structured interview. For the writing task students were given one class period (50 minutes) to draft on paper what they would write to their peer overseas to introduce themselves, including personal information, likes, and preferences. In the Colombian school the students could only use four computers located in their English classroom and they only had 20 minutes to complete the writing task at the end of the semester, while for the pretest they had had one 50-minute lesson. As a result, the final paragraphs were too short in comparison to the New Zealand paragraphs, so the last message written on Moodle was added to the paragraph written as a posttest for analysis. All the messages sent within the eight weeks were copied without modifications for safekeeping, and compiled by the order of interactions between peers in dyads (first paragraph sent by a tutee to a tutor, tutor's response, tutee's edit of the first draft, and so on).

We computed a quantitative measure of writing proficiency for the pretest and posttest from a variation of the measures of fluency, accuracy, and complexity adapted from Wolfe-Quintero, Inagaki, and Kim (1998). This measure assumes that as language learners progress, they will write sentences that are more grammatically and lexically complex, they will write with fewer errors, and they will write more words in a given time period. Following this assumption, we initially marked all the complete sentences in each paragraph written by the students. Then, we counted the total number of words in each text, the number of simple, complex, and compound sentences, the number of clauses per sentence, and the number of error-free words and sentences. For each paragraph, fluency refers to the number of words per sentence; accuracy accounts for the number of error-free words and sentences; and complexity computes the number of complex and compound sentences. To obtain total values for writing proficiency, we produced a simple average of the fluency, accuracy, and complexity measures for each paragraph.

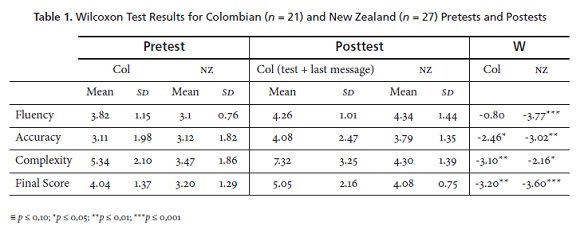

We used the Anderson-Darling normality test on the data sets for pretests and posttests to check for normal distribution. Since they did not show normal distributions, we applied the non-parametric Wilcoxon test to determine significant differences between the means of pretests and the posttests, instead of the t-Student test. The results were complemented with qualitative data from the interview, related to the learning of syntax, spelling, and punctuation in the FL.

-

To answer the second and third questions on the young learners' changes in attitudes towards FL learning and on development of the students' L1, we used data from the semi-structured interviews. In Colombia, all 21 students were interviewed by the researcher to collect comments about their experience of reciprocal peer tutoring with their peers around four themes: the online tutoring experience, perceived gains in FL, perceived gains in L1, and attitudes towards language learning. In New Zealand, 12 students chosen by the classroom teacher as representatives of three different levels of academic performance in the FL and engagement in the project were interviewed. The interviews were transcribed and their information categorized as we looked for specific information related to the three research questions.

Findings

Writing in the Foreign Language

The students' writing ability was analysed based on texts written before and after the eight week intervention. The texts were analysed for accuracy, fluency, and complexity. Table 1 shows the results of the Wilcoxon tests for pretests and posttests in Colombia and New Zealand. As can be seen, there are statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 in accuracy, complexity, and final score for the texts produced by the Colombian peers. This indicates that the number of both simple and complex sentences increased while the number of syntax, spelling, and punctuation errors decreased in the final paragraphs. However, the results for fluency, with no statistically significant difference, indicate that the number of words did not increase. These results are consistent with Lapadat (2002), who found that in tandem interaction, students tend to produce shorter messages but messages which are better constructed, more pragmatically adapted to the receiver, and more coherent. Table 1 also presents the results for the New Zealand peers, which, on the other hand, show statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 for all measures, including fluency. This may have been a result of better access to technology and more focused work in the project from the New Zealand group.

These results indicate that positive changes occurred in both groups after the intervention. It seems that the online interaction contributed to improve FL writing in both groups, in Spanish for New Zealand peers and in English for the Colombian. At the end of the intervention both groups of students wrote significantly more correct and more syntactically complex paragraphs.

These data are supported by the qualitative data of the interviews, where the Colombian students provided richer information about their learning than their New Zealand peers. Participants from both groups asserted that they learned about their FL. They identified aspects such as syntax, spelling, and punctuation as part of their learning.

In relation to syntax, 16 out of 21 Colombian peers mentioned that they learned about syntactic aspects of English such as word order, verb conjugation, and singular and plural forms of verbs and adjectives. According to them, this helped them improve their writing. On the New Zealand side, 5 out of 12 interviewed students also indicated gains in Spanish, but they only referred to word order, which seemed to be what stood out for them in their interactions.

A Colombian peer, for example, said that he learned about the order of nouns and adjectives:

[aprendí] que [en español] va primero el objeto que la cualidad [y en inglés] va primero la cualidad que el objeto, por ejemplo "my blue sweater." ([I learned] that [in Spanish] the object goes before the quality [and in English] the quality goes before the adjective, for example "my blue sweater"). (Col, 3)

This is repeated by another student:

aprendí también que primero va la cualidad y luego el objeto, por ejemplo, brown eyes en español es ojos cafés. (I also learned that the quality goes first and then the object; for example, "brown eyes" in Spanish is ojos cafés). (Col, 5)

In turn, one of the New Zealand students also talked about his learning regarding the order of nouns and adjectives in Spanish: "I used to put ‘grande' before a noun, and they say you have to put the noun first before the adjective" (NZ, 3). Other New Zealand peers also stated that they learned about word order, although they did not provide specific examples: "[In the corrections I learned things] like positions of some words the wrong way" (NZ, 2). Finally, another student said: "[I learned] where the words are put around. Uh, the word order. Yeah" (NZ, 11).

The Colombian students talked about more than word order. For example, one of them mentioned his gains in the correct use of verbs in English, which he acknowledges are used differently in Spanish: "y bueno pues uno aprende que no es have cuando [dice los] años, [ahora digo] ‘I am 12 years' (well, one learns that it is not have when [you talk about] age. [Now, I say] ‘I am 12 years')" (Col, 3).

Spelling was another aspect of learning for all students. Participants from both groups, 15 in Colombia and six in New Zealand, expressed that they also learned about spelling rules in the FL. In Colombia students highlighted their gains in the use of the capital I for the personal pronoun I:

Ahora ya sé muchas cosas de inglés, como [el uso de las] mayúsculas...siempre escribía [yo en inglés] con minúscula; [antes] se me olvidaba, pero ahora no (I know many things in English now, as [the use of] capital letters...I always wrote [I] in low case; I would forget it before, but not now). (Col, 8)

Correspondingly, five New Zealand peers also expressed their gains in spelling and mentioned their improvements in the use of accents in Spanish: "Urm...mostly it's about my spelling and...how they...put in...an e and then they have signs above them? They correct [sic] me on that" (NZ, 10). Other students also mentioned that they learned about accent placement: "[I learned] all about the accents and where it goes" (NZ, 5), or "Urm, [I learned] where the accents go above what we have" (NZ, 11). Regarding the use of accents, a Colombian peer said that he learned that these are not used in English: "yo le colocaba tilde a football y en inglés no [se usa la tilde] (I used to put the accent on ‘football' and in English [accents] are not used" (Col, 13).

Finally, both Colombian and New Zealand peers indicated that as a result of the intervention, they were more aware of the importance of punctuation in their writing. A Colombian peer said: "Aprendí [a usar] los signos de puntuación. Cuando termina una oración [debo] colocarle un punto; antes no lo hacía (I learned [to use] punctuation marks; when a sentence ends, [I have to] write a period. I didn't do it before)" (Col, 9). Another Colombian student stated that he learned that he has to use punctuation all the time: "ya sé que no se me puede olvidar [usar] los puntos y las comas (I know that I can't forget [using] periods and commas)" (Col, 3). New Zealand peers also commented on their leaning of punctuation: "[I learned sometimes punctuation" (NZ, 1); and "[I learned] how to put the exclamation mark and where to put the question mark" (NZ, 6).

L1 Development

The process of correcting their peers' messages on the platform also contributed to improve students' awareness of different aspects of their L1. In Colombia 18 out of the 21 participants confirmed this, while the other three indicated that their knowledge of L1 did not improve. On the New Zealand side, six of the 12 students interviewed expressed that correcting their peers' texts helped them improve what they knew about English. Although participants strengthened their knowledge of their L1, the gains were declared differently in each group. On the Colombian side, students highlighted their improvements in aspects such as spelling and punctuation, while New Zealand peers pointed out gains in their awareness of the meaning of their texts and the correct use of the language.

A Colombian girl, for example, indicates that she improved her spelling in the L1. She mentioned that correcting her peer's paragraphs contributed to strengthen what she already knew about Spanish, "pues uno corrige y así mejora [su propia lengua]...por ejemplo [el uso de las] tildes (you correct and that way you improve [your own L1]...for example [the use of] accents)" (Col, 4). Another student agreed with her: "sí aprendí [español] porque ellos tienen errores que uno sabe, por ejemplo [el uso de las] tildes (I did learn [Spanish] because they make mistakes that you recognize. For example, [the use of] accents)" (Col, 15).

Additionally, other students noticed the importance of the use of accents for the sake of meaning:

[Corregir fue] un poco difícil...[le corregí] las tildes, por ejemplo en papá y mamá, que [significan] diferente cuando no tienen [tilde] ([Correcting was] a little difficult...[I corrected] accents, for example in "papá-father" and "mamá-mother" whose [meaning] is different when they don't have [an accent]). (Col, 13)

There were also advances in the use of punctuation in Spanish:

Yo mejoré en puntuación [con las correcciones], porque tildes, comas y puntos antes no las tenía en cuenta [ahora sí] ([with the corrections] I improved in punctuation because before I did not care about accents, commas, and periods [now I do]). (Col, 11)

Due to the limited use of punctuation marks, it was frequent for the students to forget them:

pues a ver, yo sí corregí cosas que yo sabía, aunque a veces se me olvida al escribir...[por ejemplo usar] puntos...ahora sí me acuerdo [de usarlos] (Well, I corrected things I knew, although I forget them when I write [for example to use] periods...Now I do remember [to use them]). (Col, 10)

New Zealand peers also indicated that they improved aspects of their English. For example, a student declared that during the intervention he realized that he must be more careful in his use of the language when he is writing: "Oh, yup [I learned things about English]. Because I missed out on a few things in my own English, and when I actually see them, I can correct myself as well" (NZ, 2). Similarly, another student pointed out that he learned to pay more attention to the meaning of his texts: "Urm, I think I learned a lot about making sure that it makes sense, because I don't always check for [meaning]" (NZ, 9).

Furthermore, a student commented that she had to reflect on her L1 to both identify the correct structures of English and then be able to explain them to her peers:

if they write a sentence, it kind of makes me sit for a little while, and I keep reading it back to myself, and say, "Yeah, that's right", or "No, that's wrong", and I keep changing so I could teach them the best I could... So, if it's "My father name is Christopher", I'll read it several times, but I said it's better "My father's name is Christopher" rather than saying "My father name is Christopher"...Oh, because, well, in their example, if you break the sentence, it would be "my fathers-name is Christopher". But then, if I put an apostrophe there, it would've sound [sic] a bit different. So, then, I make it as easy as possible for them to understand. (NZ, 5)

Attitudes Towards FL Learning

In both countries the young learners who were interviewed expressed positive attitudes towards FL learning. They stated that learning the FL through interaction with native peers increased their interest in FL learning, made the learning process easier, and provided them with the opportunity to learn about their peers' lifestyles, providing them with development of intercultural understanding. Furthermore, Colombian students showed interest in receiving corrections from their peers, and also suggested extending the intervention in the school. In New Zealand, young learners expressed their interest in continuing to learn Spanish.

Students in both groups reported in the interviews that their interest in learning the FL was enhanced because of the intervention. A Colombian boy, for example, said that he felt more motivated to learn English because he was able to do it with a native speaker: "[me gustó aprender inglés con este proyecto] porque uno habla con gente que sabe inglés ([I liked learning English in this project] because you speak with people that know English)" (Col, 13). Another Colombian participant found it interesting to learn English because he participated in activities that were different from the activities they usually did in class:

Era chévere [participar en los intercambios] y lo que [estoy haciendo en el colegio para aprender inglés]...porque uno siempre tenía que estar leyendo o estudiando y uno ahora [aprende] con otras personas de otros países (It was nice [to participate in the interaction] and what I [am doing in the school to learn English]...because we were always reading or studying, and now [we learn] with people from other countries). (Col, 9)

Likewise, learning Spanish through interaction with native speakers was also positive for New Zealand students: "[This project makes me more interested in learning Spanish because] we were partners, with someone from their country, doing it with us, and helping...Yeah. [It is more interesting] than just the thing from the teacher" (NZ, 11). Additionally, another student highlighted the fact that he had the opportunity to learn with other peers because they faced similar difficulties:

It was a fantastic experience to me, because I found it really easy to communicate with them, and at times, they would write back my suggestions but I couldn't really understand it at the very beginning because they replied in Spanish and said "bla bla bla; you didn't quite get this right." And then when I was giving the suggestions, I use them in English as well, so then, I kinda felt like they knew how I was feeling when I see it in Spanish. (NZ, 5)

The interaction with native speakers also facilitated the FL learning process, as stated by a Colombian young learner: "[me gustó] mucho, porque como ellos nacieron hablando inglés...como que se le hace más fácil a uno aprenderlo (I liked it very much, because since they were born speaking English...it seems easier for one to learn it)" (Col, 8). This was reiterated by one of his classmates:

[me gustó aprender inglés con este proyecto] porque uno habla con gente que sabe inglés y ellos hablan siempre inglés, [y] así aprende uno más con gente que...le enseñen a uno ([I liked learning English in this project]) because we speak to people that know English and they always speak English...so, we learn more with people...that teach us). (Col, 9)

A New Zealand peer added that age closeness also facilitated the interaction: "Urm, I think it's just a lot easier if you work with someone of your same age because it's like...you understand it a little more better [sic] what each other is talking about" (NZ, 5).

Students in both Colombia and New Zealand mentioned that they enjoyed learning the FL through interaction with other students overseas because this allowed them to learn about their peers' culture and lifestyle, as a Colombian peer stated:

Me gustaba mucho [participar en este proyecto] porque hablábamos con gente de otros países. [Aprendí que a] Alex le gusta mucho el hockey y es de China. [Me gustó] porque nos comunicábamos con ellos (I liked [participating in the project] very much because we talked with people from other countries. [I learned that] Alex likes hockey very much and that he is from China. I liked it because we communicated with them). (Col, 9)

Another student also mentioned what he learned about his peer's culture:

[Aprendí que mi amiga] es [de la] India; la mamá trabaja en un restaurante [indio]; ella en su lonchera lleva muchas cosas de su país ([I learned that my friend] is [from] India; her mom works in an [Indian] restaurant; she packs many things from her country in her lunch box). (Col, 17)

Similarly, New Zealand peers said that they enjoyed learning Spanish with the Colombian students because they also learned about the country and the culture: "because it was fun learning Spanish too; then I got to learn about other people's culture and them and everything [sic]" (NZ, 11). They also had the opportunity to identify the differences between New Zealand and Colombia:

Oh yeah! Learning Spanish is really fun, and... in the text, I think is better because...now I know that their lifestyle is not the same as ours, and their city is very crowded, and they have a lot different lifestyle to the people in New Zealand [sic]. (NZ, 2)

Colombian participants were pleased when they had their texts corrected. Corrections made them feel confident and stimulated their learning:

Ellos nos corregían...eso era bonito porque como ellos saben inglés le enseñaban a uno...porque aprendí más, porque él me corregía palabras y todo (They corrected us...that was good because they know English and they taught us...because I learned more, because he corrected my words and everything). (Col, 11)

The young learners accepted the corrections and considered them as a part of their learning process:

[Me gustó participar porque] ellos nos enseñan inglés, hacemos textos y ellos nos corrigen...porque si yo lo hacía bien ella me felicitaba y si no pues ella me corregía...porque sólo en medio de textos puedo aprender más cuando nos corrigen nuestros errores ([I liked participating because] they teach us English, we write texts and they correct them...because if I wrote correctly, she congratulated me, and if I didn't, she corrected me...because just through texts I can learn more when they correct my mistakes). (Col, 12)

Some students in Colombia considered it important to extend the project in the school:

Hacer esto [los intercambios] en el colegio es bueno, porque uno conoce nueva gente y pues eso lo anima a uno [a aprender] (Implementing this [the tandem] in the school is good because we can meet new people and this encourages us [to learn]). (Col, 19)

One of his classmates agreed with him:

[A mí me gustaría] que todos los [niños] del colegio también [participaran], porque ellos también [aprenderían y] conocerían nueva gente y pues eso lo anima a uno [a aprender] ([I would like] for all the students in the school to participate, because they would also [learn and]...meet new people. So, it encourages us [to learn]). (Col, 15)

Finally, some New Zealand students said that after participating in the project they felt motivated to continue learning Spanish: "It makes me want to do it even more because when I made a mistake, it makes me want to try harder to make it correct" (NZ, 9). One of his classmates also stated that he was interested in learning more Spanish: "I like learning Spanish with this project because I like meeting new people and it was fun talking to Colombians, and I still go on about my Spanish thing" (NZ, 10).

Discussion

This study sought to assess the impact of tandem communication between young learners of English and Spanish as foreign languages in Bogotá, Colombia, and Auckland, New Zealand, on their skills in FL writing, their attitudes towards FL learning, and their knowledge of their L1. The results are positive in the three aspects of learning studied in both groups of students. Quantitative analysis showed statistically significant differences between the means of pretests and posttests, with an advantage for the posttests in the measures of the students' writing. Analysis of the interviews provided further information on the students' language learning as well as their report of positive changes in attitude toward FL learning. Furthermore, the students expressed having liked the opportunity to interact with and learn from peers from a distant country. Such positive results are remarkable and all the more meaningful considering the great differences in the conditions in which the two groups worked.

In a previous study of tandem corrective interaction between similar groups of Colombian and New Zealand beginners (Tolosa et al., 2015), where we focused on comparing types and frequency of feedback produced by the participants, we provided a plausible explanation for these similar positive learning outcomes which seem to originate in the tandem intervention. Our previous study indicates that even though the students could not identify all the errors produced by their peers, the tandem activity provided a proper context for language practice and authentic interaction, where peers were a real audience for each other. Similar results were also reported by Ware and O'Dowd (2008) and Lafford and Lafford (2005) who emphasized the importance of meaningful communicative engagement and the motivation that a real audience provides to writing in an FL. Conscious reflection on language form required by the tandem format has been found to improve FL skills (Fantuzzo & Ginsburg-Block, 1998), even if there are variations on writing accuracy (Canga Alonso, 2012), both of which were observed in the present study.

Another characteristic of the participants in the present study— which makes it surprising that all actually developed both FL and L1 through their interaction— is their very beginning level of proficiency in the FL. In our previous study (Tolosa et al., 2015), we reported that our participants, also at a very low level of FL language development (i.e., CEF A1), read each other's messages with real interest in what they said, acted as experts in their L1, and accepted their peers' novice level in it because they knew they were also novices in their respective FL. The qualitative data from the present study show similar high levels of motivation and willingness to participate in the interaction in the two groups of students. As Brammerts (1996) asserts, learners in tandem arrangements are interested in each other as individuals as well as sources of language input. This interest transpired in the interviews carried out in the present study; the students felt comfortable with each other since they shared the beginners' learning path while at the same time relied on each other's expertise in their L1s.

Other disadvantages shared by all participants were revealed in our previous study (Tolosa et al., 2015) when we noted that the same intervention produced interactions limited in content and scope because of the low level of proficiency of the students and limited collaboration established by the one-way descriptive texts interchanged. We also found that the tutees did not follow up on their peers' feedback but just accepted the direct correction of their errors, which prevented the detection of conscious gains in the process and pointed towards the need for more instruction on giving and receiving feedback and more teacher intervention and monitoring of the interaction process. But in spite of all this, tandem interaction seems to make a real difference. The significant advance it produces in FL writing and the motivation it causes in the participants towards FL work after a very short intervention, even under unfavorable conditions, speak for its potential for exploitation as a learning environment. The fact that the students spoke about the mechanics of writing in the interviews seems to indicate that they have all developed their metalinguistic skills, a common outcome of tandem interactions (Thurston et al., 2009). The principle of autonomy of tandem exchanges resulted in enhanced academic skills and metacognitive strategies for these learners, such as analysing their language learning process and recognizing different ways in which their own languages work. For 21st century learners, these skills may be valuable not only for their language learning. The promise of CMC seems to be its potential to bridge learning contexts and facilitate the delivery and construction of knowledge while allowing for personal and ubiquitous connections among learners and between learners, teachers, and their technological environments (Crompton, 2013).

There was little doubt that learners in both contexts would be motivated to engage in authentic communication with peers of their same age. The intercultural gains cited in other studies (Guth & Helm, 2010; Ware & Kessler, 2013) were evident in many responses during the interviews. The opportunity to interact with real speakers of the language was a first for most learners in both contexts. They were curious and delighted to learn about each other, yet frustrated that their FL was limiting. However, having eight weeks to know each other gave students the sense of belonging to a wider community of FL learners, one that they would like to continue and extend to others in their schools.

Finally, there is a methodological achievement in the present study in spite of its exploratory nature and small size: It was able to detect formal gains in FL writing and gains in L1 metalinguistic knowledge. This had been impossible in our previous study (Tolosa et al., 2015), where we tried detecting these gains in the messages interchanged in the virtual platform and failed because of the characteristics of the interchange and the lack of training and monitoring mentioned above.

Final Remarks

This study has provided further evidence of the potential of CMC to enhance FL learning. Even under unequal circumstances, the young learners (and their teachers) in this study persevered in communicating with each other driven by the motivation to learn about each other and from each other. Linking classrooms through online tools that are increasingly ubiquitous and affordable may be the site of language learning preferred by learners in this century.

A clear limitation of the study is the sample size of the two classrooms, as well as the different conditions under which the schools worked. However, with gains in FL, L1 and intercultural understanding, this small scale study presents a model that could be expanded and replicated with learners in different contexts and different languages. Tandem learning in online spaces at school level seems a promising way forward for learners and teachers as well as for researchers.

References

Andrews, R., & Haythornthwaite, C. (2007). Introduction to e-learning research. In R. Andrews & C. Haythornthwaite (Eds.), The sage handbook of e-learning research (pp. 1-57). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607859.n1. [ Links ]

Brammerts, H. (1996). Language learning in tandem using the Internet. In M. Warschauer (Ed.), Telecollaboration in foreign language learning: Proceedings of the Hawai'i symposium (pp. 121-130). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai'i Press. [ Links ]

Canga Alonso, A. (2012). La pareja tándem como modelo para el aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera [The tandem partner as a model for learning a foreign language]. Escuela Abierta, 15, 119-142. [ Links ]

Crompton, H. (2013). A historical overview of mobile learning: Toward learner-centered education. In Z. L. Berge & L. Y. Muilenburg (Eds.), Handbook of mobile learning (pp. 3-14). Florence, KY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Dooly, M., & O'Dowd, R. (2012). Researching online interaction and exchange in foreign language education: Introduction to the volume. In M. Dooly & R. O'Dowd (Eds.), Researching online foreign language interaction and exchange: Theories, methods and challenges (pp. 11-44). Frankfurt, DE: Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-0351-0414-1. [ Links ]

Fantuzzo, J., & Ginsburg-Block, M. (1998). Reciprocal peer tutoring: Developing and testing effective peer collaborations for elementary school students. In K. Topping & S. Ehly (Eds.), Peer assisted learning (pp. 123-144). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

González-Lloret, M. (2003). Designing task-based call to promote interaction: En busca de esmeraldas. Language Learning & Technology, 7(1), 86-104. [ Links ]

Greenfield, R. (2003). Collaborative e-mail exchange for teaching secondary ESL: A case study in Hong Kong. Language Learning & Technology, 7(1), 46 -70. [ Links ]

Guth, S., & Helm, F. (Eds.). (2010). Telecollaboration 2.0: Language, literacy and intercultural learning in the 21st century. Bern, DE: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Hyland, K. (2003). Second language writing. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667251. [ Links ]

Hyland, K., & Hyland, F. (2006). Feedback on second language students' writing. Language Teaching, 39(2), 83-101. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444806003399. [ Links ]

Kern, R. G. (1995). Restructuring classroom interaction with networked computers: Effects on quantity and characteristics on language production. Modern Language Journal, 79(4), 457-476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1995.tb05445.x. [ Links ]

Kitade, K. (2008). The role of offline metalanguage talk in asynchronous computer-mediated communication. Language Learning and Technology, 12(1), 64-84. [ Links ]

Lafford, P. A., & Lafford, B. A. (2005). CMC technologies for teaching foreign languages: What's on the horizon? CALICO Journal, 22(3), 679-709. [ Links ]

Lantolf, J. P. (2012). Sociocultural theory: A dialectical approach to L2 research. In S. M. Gass & A. Mackey (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 57-72). New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal1084. [ Links ]

Lantolf, J. P., & Thorne, S. L. (2006). Sociocultural theory and the genesis of second language development. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lapadat, J. C. (2002). Written interaction: A key component in online learning. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2002.tb00158.x. [ Links ]

Long, M. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413-468). New York, NY: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Manchón, R. M. (Ed.). (2011). Learning-to-write and writing-to-learn in an additional language. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.31. [ Links ]

Mendonça C. O., & Johnson, K. E., (1994). Peer review negotiations: Revision activities in ESL writing instruction. TESOL Quarterly, 28(4), 745-769. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587558. [ Links ]

O'Dowd, R., & Ware, P. (2009). Critical issues in telecollaborative task design. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 22(2), 173-188. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220902778369. [ Links ]

Philp, J., Adams, R., & Iwashita, N. (2014). Peer interaction and second language learning. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Salaberry, R. (1996). A theoretical foundation for the development of pedagogical tasks in computer mediated communication. CALICO Journal, 14(1), 5-34. [ Links ]

Thurston, A., Duran, D., Cunningham, E., Blanch, S., & Topping, K. (2009). International online reciprocal peer tutoring to promote modern language development in primary schools. Computers & Education, 53(2), 462-472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.03.005. [ Links ]

Tolosa, C., Ordóñez C. L., & Alfonso, T. (2015). Online peer feedback between Colombian and New Zealand FL beginners: A comparison and lessons learned. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 17(1), 73-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n1.41858. [ Links ]

Van den Branden, K. (2006). Introduction: Task-based language teaching in a nutshell. In K. Van den Branden (Ed.), Task-based language education: From theory to practice (pp. 1-16). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667282.002. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Ware, P., & Hellmich, E. (2014). CALL in the K-12 context: Language learning outcomes and opportunies. CALICO Journal, 31(2), 140-157. https://doi.org/10.11139/cj.31.2.140-157. [ Links ]

Ware, P., & Kessler, G. (2013). CALL and digital feedback. In M. Thomas, H. Reinders, & M. Warschauer (Eds.), Contemporary studies in linguistics: Contemporary computer-assisted language learning (pp. 323-340). London, UK: Continuum. [ Links ]

Ware, P., & O'Dowd, R. (2008). Peer feedback on language form in telecollaboration. Language Learning & Technology, 12(1), 43-63. [ Links ]

Warschauer, M. (1997). Computer-mediated collaborative learning: Theory and practice. Modern Language Journal, 81(4), 470-481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1997.tb05514.x. [ Links ]

Warschauer, M. (2005). Sociocultural perspectives on CALL. In J. Egbert & G. M. Petrie (Eds.), CALL Research Perspectives (pp. 41-51). New York, NY: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Wolfe-Quintero, K., Inagaki, S., & Kim, H.-Y. (1998). Second language development in writing: Measures of fluency, accuracy, and complexity. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press. [ Links ]

About the Authors

Constanza Tolosa: lecturer and teacher educator in foreign language education, Faculty of Education, The University of Auckland, New Zealand. She is currently involved in projects on the implementation of the language curriculum in primary schools in New Zealand and the use of technologies in language teaching and teacher education.

Claudia Lucía Ordóñez: associate professor, Faculty of Human Sciences and Faculty of Engineering, Universidad Nacional de Colombia - Sede Bogotá. Her research explores pedagogical innovation and its impact on learning in all academic areas, with emphasis on language education.

Diana Carolina Guevara: English teacher, English Service Programme, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, currently a candidate for the Masters in Applied Linguistics-Spanish as a Foreign Language, at Universidad Javeriana. Her research interests are the use of technologies in foreign language teaching and bilingual education.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the teachers and students who participated in this project, especially Dora Inés Mesa, the Colombian teacher whose Master's thesis inspired this article. Data analysis was partially funded by a mobility grant from Colciencias (Conv. 650-2014).