Introduction

It has long been acknowledged that a learner’s first language (L1) has a considerable influence on both the acquisition and use of second language (L2) vocabulary (Swan, 1997). This influence often manifests itself in lexical errors in oral and written production which are seemingly difficult for the learner to eradicate. The fossilization of erroneous lexical forms is especially likely when learners are in a monolingual educational environment, as much of their exposure to English comes from other language learners who share the same L1, such that the same errors are reinforced and normalized.

This problem is compounded by the fact that teaching materials often come in the form of course books which are designed for the international market and therefore cannot address the common lexical errors that speakers of one specific L1 are prone to. As a consequence, teachers may give too little attention in class to dealing with these errors and to raising awareness amongst learners of how L1 can help or hinder accurate vocabulary use.

University students for whom English is an integral part of their degree programme often need to achieve a high level of linguistic competence and accuracy, which means that basic vocabulary errors need to be minimized, or if possible eliminated. I therefore perceived a clear need for this issue to be addressed in some way in my context, since, although there has been considerable research on the effect of L1 influence on second language acquisition (SLA), little has been written about how to approach the problem of negative lexical transfer in the classroom.

Literature Review

Two main areas of the literature were instrumental in framing this research. These were the influence of L1 on second language learning, especially in the area of vocabulary acquisition and production, and intentional versus incidental second language vocabulary learning.

To consider how far L1 influence may hinder second language learning, we need to have a clear understanding of the phenomenon. However, Jarvis (2000) points out that despite decades of research in this area, there is still no commonly accepted definition of L1 influence or even agreement that such a definition is possible. Perhaps because of this fundamental problem, there are also widely varying estimates of how many errors in L2 production can be attributed to L1 influence, with some studies claiming them to be as low as 3%, and others as high as 51% (Ellis, 1985). Against such uncertainty, Jarvis settles on a definition of L1 influence on SLA as “any instance of learner data where a statistically significant correlation . . . is shown to exist between some feature of learners’ [interlanguage] performance and their L1 background” (p. 252).

Jarvis and Pavlenko (2008) identify nine categories of linguistic transfer: phonological, orthographic, lexical, semantic, morphological, syntactic, discursive, pragmatic, and socio-linguistic. Much of the literature focuses on grammatical structure, perhaps because it is where the majority of negative transfer occurs. For example, in one study of Spanish high school students, Alonso (1997) found that of 138 interlingual errors, 96 were due to transfer of grammatical structure. Despite these findings, lexical transfer errors deserve attention for two reasons: first, lexical selection consists mainly of content words, and so errors of this type are potentially very disruptive as they may impede communication, in particular placing a greater burden on the reader of written production (Hemchua & Schmitt, 2006). The second reason is that English language course books largely deal with the types of grammatical errors Spanish speakers make, since these are more universal in nature than the specific lexis which causes problems.

Alonso (1997) identifies three ways in which negative lexical transfer from Spanish to English may occur: overextension of analogy (false cognates), substitution errors, and interlingual/intra-lingual interference. False cognates are words which have identical or similar forms in English and Spanish, but which have different meanings. A typical example is the Spanish word sensible, which means sensitive in English. The overextension of analogy by Spanish speakers leads to mistakes such as: “I can’t go out in the sun much, as I have very sensible skin”. Substitution errors are seen as those in which the learner uses a direct translation of a word or expression in Spanish in a context which is not appropriate in English. A common example is the use of the word “know” in the sentence “I would like to know France” (Quiero conocer Francia). Although conocer can be expressed by the word know in many contexts, in this one, it is inappropriate. Finally, interlingual/intralingual interference errors refer to cases where there is word distinction in L2 where none exists in L1. An example is the sentence “I arrived late because I lost the bus.” The distinction is made in English between lose and miss, whereas in Spanish, only perder is used.

Although these errors would affect intelligibility for native English speakers, they may not necessarily cause problems of communication between L2 learners in a monolingual classroom context. This is because they sound familiar, precisely because they come from the learners’ L1. The familiarity of, and familiarization with, these erroneous forms in the monolingual classroom is highlighted by Amara (2015) as one reason why it is important to carry out correction, since “there is the danger that by leaving errors untreated, the defective language might serve as an input model and be acquired by other students in the class” (p. 61).

L1 often plays a positive role in SLA and may account for much of what is correct in a learner’s interlanguage (Swan, 1997). According to Hulstijn (2001), “beginning L2 learners . . . often appear to link the L2 word form directly to a corresponding L1 word form” (pp. 260-261). So, at an early stage of learning, L1 may aid L2 vocabulary knowledge. However, as Swan (1997) points out, learners will repeatedly make mistakes with words they have learnt correctly,1 especially if the knowledge of a particular language item is not reinforced through repeated exposure and rehearsal. Frantzen (1998) echoes this point, noting that “even after students are repeatedly exposed to the target language meanings of false cognates, they continue to misuse them in their speech and writing” (p. 243). Swan says that when retrieving lexical items for recall, learners usually have to choose from a number of possibilities, and often select the language form that most resembles a counterpart in L1 because they have more fully automated control over this form than the correct target language equivalent. Kavaliauskiene (2009) suggests that negative transfer errors may occur because learners lack the attentional capacity to activate the correct L2 form.

Swan (1997) points out that between closely related languages, there is more transfer, and therefore more scope for interference errors as learners equate forms which are similar, but have different meanings. Corder (1983) claims that the greater the perceived distance between the language being learnt and the learner’s L1, the less likely the learner will be to borrow from the L1 and hence there will be fewer “borrowing errors” (p. 27). However, he suggests the highest incidence of this type of error will occur in languages which are “moderately” similar rather than those which are closely related. Since English shares a common linguistic root with Spanish, yet is not as closely related to it as Romance languages such as Italian or Portuguese are one should expect the incidence of L1 transfer errors from Spanish-speaking learners of English to be fairly high.

Raising learners’ awareness of cross-linguistic transfer in order to facilitate linguistic development is seen as essential by a number of researchers. Swan (1997) points out that improved understanding of the similarities and differences between L1 and L2 will help learners “to adopt effective learning and production strategies” (p. 179). Talebi (201)4, who conducted research on cross-linguistic awareness amongst Iranian learners, considers that teachers have a responsibility to raise learners’ awareness by using materials which are specifically designed for the purpose of teaching for transfer. This point is echoed by Kavaliauskiene and Kaminiskiene (2007), whose study indicates that the use of translation as a learning tool facilitates the raising of linguistic awareness in learners of English for specific purposes.

Considering the problems caused by negative lexical transfer, and the difficulty of eradicating fossilized lexical transfer errors in a monolingual English as a foreign language context, it is important to consider how they can be dealt with in the classroom. However, there seems to be little research in this area. In the next part of my review, therefore, I focus more broadly on research on vocabulary teaching and how this affects acquisition, retrieval, and production of lexis.

Much of the literature on vocabulary acquisition has addressed the comparative benefits of incidental versus intentional vocabulary learning. Hulstijn (2001) defines incidental vocabulary learning as “the learning of vocabulary as a by-product of any activity not explicitly geared to vocabulary learning” and intentional vocabulary learning as “any activity aiming at committing lexical information to memory” (p. 270). Krashen (1989) contended that learners will acquire all the vocabulary they need through extensive reading, and that therefore teachers should promote activities which are conducive to incidental learning and discourage intentional vocabulary learning procedures.

However, the position that exposure alone is enough to ensure effective vocabulary learning is not widely supported. Nation (2001) accepts that large amounts of incidental vocabulary learning will result from the reading of large quantities of comprehensible text, but holds the view that some vocabulary requires special attention and therefore, teachers should deal with it in a principled and systematic way. He believes that the giving of elaborate attention to a word or words, which he terms “rich instruction”, can be of real benefit to the L2 learner, especially when dealing with high-frequency items which are deemed important or are of particular use to the students, and when it is not to the detriment of other components of the course.

According to Nation (2001), there are three important steps which facilitate the learning of new vocabulary: noticing, retrieval, and generation. Noticing can happen in a number of ways, but basically implies decontextualization, whereby attention is given to a lexical item as part of the language rather than part of the message; retrieval is when a learner needs to express the meaning of a certain item and is obliged to retrieve its spoken or written form; and generation implies the production of the item in new ways and/or new contexts. For Nation, these processes are essential for effective learning.

It is also important to understand that learners have a receptive and productive vocabulary. Schmitt (2008) states that since “acquiring productive mastery of vocabulary is more difficult than acquiring receptive mastery” (p. 345), it cannot be assumed that having receptive exposure will automatically lead to productive mastery. He believes that words acquired by incidental learning are unlikely to be learned to a productive level and that recall learning from reading is more prone to forgetting than recognition learning. He concludes that for productive mastery to be developed, learners need to engage in productive tasks. For Schmitt, the idea of engagement is central to the effectiveness of vocabulary learning. This encompasses a range of factors, such as time spent on a lexical item, the attention given to it, increased noticing of lexical items, manipulation of the target item, and a requirement to learn. He sees the promotion of high levels of engagement with the lexis as a fundamental responsibility of researchers, materials writers, teachers, and students.

Hulstijn (2001) highlights the importance for learners to attain quick and automatic access to vocabulary (automaticity). He points out that rich, elaborate processing on its own is not sufficient for this, and that frequent reactivation of lexical forms is also essential. For this, he proposes the allocation of sufficient classroom time for deliberate rehearsal of problematic lexis and the recycling of previously seen items. Schmitt (2008) also highlights the importance of increasing the automaticity of lexical recognition and production, noting that “knowledge of lexical items is only of value if they can be recognized or produced in a timely manner that enables real-time language use” (p. 346).

Drawing on this literature, this study focused on a number of specific areas. The first of these was the need to raise learner awareness of the issue of negative transfer amongst Spanish-speaking learners of English. Due to the relative proximity of Spanish and English lexis, and therefore the scope for erroneous transfer, the focus was lexical interference. Jarvis’ (2000) definition of L1 influence was used to justify the choice of lexical transfer errors analysed in the study, as was Alonso’s (1997) taxonomy of L1 errors, since this came from a study of Spanish-speaking learners. Finally, the study aimed to increase learner engagement with problematic lexis as a way to improve their attentional capacity and automaticity. Translation activities were employed to raise awareness of L1/L2 difference and correspondence. Also, Nation’s (2001) three steps were employed as part of the lexical analysis and practice: close analysis of erroneous and correct lexical usage (noticing), oral and written translation exercises and controlled practice oral discussion activities (retrieval), and mini-presentations and small group discussions of word pairs (generation).

My research questions were as follows:

Method

This study was conducted within the context of a year-long teachers’ action research programme in 2016 at the Universidad Chileno-Británica de Cultura (UCBC). UCBC is a small, private university in Santiago, Chile, offering undergraduate degrees in translation, secondary English teaching, and primary teaching and nursery school teaching with a special focus on English. It is an action research project which addresses a local problem and follows the cycle of planning, implementation, observation, and reflection to bring about change and improvement in practice (Burns, 2015). In this section, I will first describe the participants, then the design and realization of the implementation stage, and finally the data collection and analysis.

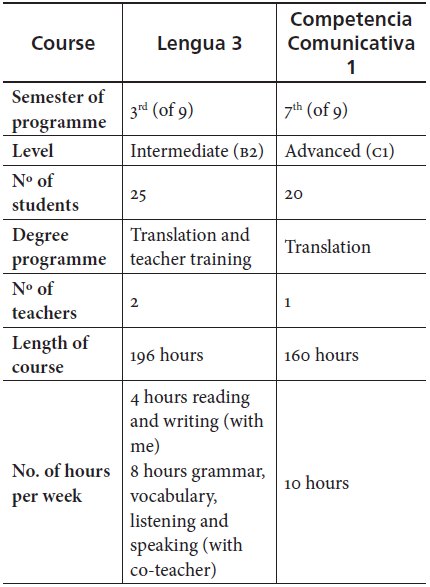

My project was carried out with two groups of UCBC students over a 13-week period during the first semester of 2016. Both groups were studying in general English language courses as part of their degree programmes. An overview of the profile of these groups can be found in Table 1. One of these courses was Lengua Inglesa 3 (English Language 3), which students take in the first semester of their second year, and the other was Competencia Comunicativa 1 (Communicative Competence 1), which is taken in the first semester of the fourth year. The former class was made up of 25 students from both translation and teacher training degree programmes. They had an intermediate/upper-intermediate level of English and were using a Cambridge First Certificate in English (FCE) course book as part of their course material. The FCE examination corresponds to a level B2 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). The latter class consisted of 20 students from the translation degree programme, who had an advanced level of English and were using a Cambridge Certificate in Advanced English (CAE) course book (CEFR level C1).

I taught the Lengua 3 course with another teacher, who focused on grammar, vocabulary, listening, and speaking. That component took up two thirds of the course time. The remaining component, which I taught, focused on reading and writing. In the Competencia Comunicativa 1 course, I was the only teacher. Students in both courses are assessed by means of written tests, oral tests/presentations, and written assignments throughout the term (70% of their final mark) and three final exams (use of English and listening, reading and writing, and oral) which have a weighting of 30% of the final mark. I decided to carry out the project with two groups to see how useful it would be for students at different stages of the language learning process. All of the participants were Chileans and native Spanish speakers. Their ages ranged from 20 to 30, but the majority of them were in their early 20s.

My initial task for this research project was to develop a bank of typical L1 errors. My main considerations when choosing the lexical items to be included were frequency of error occurrence and intelligibility of the erroneous form to a native English speaker-intelligibility because such errors are greater obstacles to communication, and frequency because high-frequency lexis merits attention if students are aiming for productive mastery. I developed the word bank from my memory of typical lexical transfer errors made in class, along with examples I found in approximately 75 second and third year students’ written examinations from previous years. This list was then cross-referenced with examples given to me by university colleagues and other English teachers who had been informed of my project. I subsequently selected 40 items to use in the input sessions, taking into account the two considerations previously mentioned of frequency and intelligibility.

I programmed 13 weeks for the intervention, setting aside between 45 and 60 minutes of class time per week. In week 1, students were asked to complete a pre-test to establish the extent of their knowledge of some of the target lexis and also to provide a point of comparison for the post-test which would be used at the end of the project. In week 2, students were informed about the objectives of the project, asked to complete a questionnaire, and given an explanation of key concepts, such as transfer, L1 interference, cognates, and so on. Finally, the participants were asked to read a document about the purpose and nature of the study, and to sign a consent form if they wished to participate; all of the students agreed to do so.

The teaching input and analysis of the lexical items took place from weeks 3 to 12 and took two main forms: teacher-led activities, which involved the analysis of a short text or series of sentences which I devised, and student-led activities, which took the form of mini-presentations followed by small group discussions. My programme allowed for eight input sessions, in each of which five lexical items would be analysed, thus covering the 40 items selected from the word bank. This approach allowed time for testing, feedback, revision, and quizzes (see Table 2).

Table 2 Overview of Project Programme

| Week | Intervention | Data Collection |

| 1 | Pre-test | |

| 2 | Introduction to project: Objectives and key concepts | Questionnaire/Audio recording of students |

| 3-12 | Teacher-led activities: 5 x textual analysis input sessions 2 x revision sessions Student-led activities: 3 x mini-presentations | Mid-project feedback (audio-recorded) |

| 13 | Post-test Audio-recorded focus group meetings |

The pre-test contained two types of items:

Items 1-8 - Translation: The first set of items contained eight sentences in Spanish, sections of which the students were asked to translate into English. Most of the underlined sections contained words or expressions in L1 where students often make mistakes due to negative transfer (see Figure 1, i.).

Items 9-16 - Error identification. The second set of items was an error correction exercise, in which students were given eight sentences and asked to identify errors. The students were told that the sentences may contain one, two, or no errors. Again, these errors were typical L2 lexis errors that come from L1 interference (see Figure 1, ii.).

Before the pre-test was carried out, students were informed that it was a general diagnostic test which had no bearing on their course evaluation, and therefore they were not aware of what specific aspect of language use was being assessed. My aim was to obtain as accurate an idea as possible of the problems these lexical items caused. All the items in the test were included in the input during the following weeks along with other items from my word bank.

The first stage of each of the five teacher-led activities-the “textual analysis input sessions” (see Table 2)-consisted of identifying errors in a short text or series of questions in English. Students were given a few minutes to read the text/sentences and identify the errors. By this stage, they were aware that they were looking for examples of negative transfer. There then followed whole class feedback and analysis of the errors, during which students were encouraged to suggest why a Chilean Spanish speaker might make them. Students were encouraged to make a note of these items in their notebooks to build up a word bank of L1 interference items containing examples of misuse and correct usage. The final stage was a controlled practice activity. This activity was usually done as a written translation where half the students in the class were given one set of sentences and the other half given a different set to translate into Spanish. Both sets contained the target language and students were encouraged to use natural Spanish. They then swapped their papers with someone from the other group and translated their classmates’ Spanish sentences back into English, being careful to avoid erroneous L1 transfer. When done orally, the activity involved splitting the class into two groups with different texts to translate into Spanish. Students were then paired off (one from each group) to read their translations to their partner, who had to translate it back into English, again being careful to avoid L1 interference. An example of a written translation activity can be seen in Appendix A.

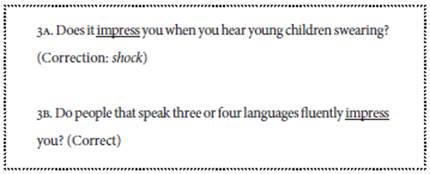

This translation stage was not employed in all of the five teacher-led sessions. On one occasion, the error identification stage came in the form of a series of pairs of questions, such as those in Figure 2. Each pair contained the same word, once correctly used, and once erroneously used as a result of typical L1 interference. In this case, following the identification, analysis, and recording stages, the students were asked to discuss the questions in pairs. They were then given just the target lexis, isolated from the questions on the board and asked to discuss the questions again with a new partner.

The student-led activities were a series of three mini-presentations. On each occasion, four or five volunteers from each class were given five pairs of words-one in English and one in Spanish (see Appendix B). The volunteers each prepared a short oral presentation which explained the usage of the words in English and Spanish, highlighting any correspondence and difference between the two and giving examples. They delivered their presentations individually in class the following week to a group of about five students. After 15-20 minutes, I drew the different groups together as a whole class, and we discussed their ideas. I gave feedback and examples for the class to record. (During this stage and the presentation stage, words also came up in discussion which had not been in the word pairs, such as the words “bookshop” and “stationer’s” which came up when analysing “librería - library”). A controlled practice activity followed, in which students used the target vocabulary to complete a series of opinion questions. In the final stage, students discussed the questions in pairs.

As well as these presentations, all students from the fourth-year class prepared a separate presentation of between five and ten minutes, delivered in pairs, which involved them recording (or finding a recording of) a native Spanish speaker talking in English. They analysed the recording and presented it to the class, commenting on any examples of L1 interference.

In order to answer the first research question regarding the impact of the intervention on students’ lexical errors, quantitative data in the form of results from the two tests were collected. The pre-test has been described in some detail in the section above. The post-test was carried out in the final week (13) of the study. It was the same as the pre-test in terms of format, and included many of the lexical items from that test and also some items that had not been in the initial test, but had been analysed in class over the course of the project.

In order to address the second research question regarding the students’ perceptions of the intervention, qualitative data were collected at the beginning of the project, mid-project, and at the end: Prior to the beginning of the input and practice sessions (week 2) students completed a questionnaire and, audio recordings of students’ opinions were made. Students’ opinions were also recorded mid-project (week 7) and immediately after the post-project test (week 13).

Students’ opinions were collected post-project via focus discussions with five members of each class. The discussions lasted about 20 minutes each and were audio-recorded. These were semi-structured interviews whose aim was to remind students of the objectives of the research project, ascertain whether, in their opinion, these had been achieved, and get a general idea of how useful they thought the project had been. The interviews were carried out in English and Spanish. (Questions were asked in English, but students were encouraged to respond in Spanish if they felt they could express themselves more clearly in that language). These interviews took place immediately after the post-project test and I invited students who tended to be more willing to express their opinions in class to participate so as to maximize the data I would receive. The audio recordings from the focus group sessions were later transcribed so that they could be analysed more thoroughly.

Findings

The data collected from the tests, questionnaire, recorded group discussions, and focus groups are presented and analysed here with reference to my two research questions.

Research Question 1: Would a sustained, explicit, systematic approach to addressing the transfer of L1 lexical errors reduce the production of this type of error by students?

Not all of the students who completed the pre-test completed the post-test (see Table 3).This was particularly true of the Lengua 3 group, whose low attendance may have been due to students’ perceived need to study for tests in other subjects during this period.

Table 3 Number of Students Who Completed Pre- and Post-Tests

| Course | Nº of students who did pre-test | Nº of students who did post-test | Nº of students who did both tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| L3 (2nd year) | 24 | 13 | 12 |

| CC1 (4th year) | 20 | 17 | 17 |

In both the pre- and the post-tests, each question was marked either correct or incorrect. In some cases, half marks were given (if an expression was wrongly translated but without signs of L1 interference in Item 1, and where an error was correctly identified but not corrected in Item 2). Although the allotting of half marks in this way is somewhat subjective, I strove to maintain consistency in the marking of both tests. The marks for each student’s test were then transformed into a percentage and an average was calculated for the whole group.

Table 4 shows that both groups improved their scores on both translation and error correction exercises. The post-test results for the fourth-year group are around 20 - 25% higher than the pre-test results, and those of the second-year group are around 30 - 40% higher. The final column shows that almost all, and in one case all, of the students improved their individual marks in the post-test.

Table 4 Comparison of Results From Pre- and Post-Tests

| Group | Pre-test results - average scorea | Post-test results - average score | Difference in results between pre- and post-test scores | Number of students who improved their score | |

| 4th year (CC1) | Item 1 (Translation) | 68% | 87.5% | 19.5% | 17/17 |

| Item 2 (Error correction) | 45% | 72% | 27% | 14/17 | |

| 2nd year (L3) | Item 1 (Translation) | 37% | 66% | 29% | 10/12 |

| Item 2 (Error correction) | 13% | 52% | 39% | 11/12 | |

a These averages are taken solely from the results of the students who also took the post-test. The averages of all students who took the pre-test diverged negligibly from the averages shown (0% - +2.5%).

Research Question 2: How would students respond to a sustained, explicit, systematic approach to addressing the transfer of L1 lexical errors?2

The questionnaire which students were asked to complete in week 2 was in English and required them to provide their names and ages. The aims of this instrument were: to obtain information about students’ exposure to native English speakers; to gauge how aware they were of the problem of L1 interference; to find out if and how the issue had been addressed in their previous classes; to ascertain whether they thought it useful to spend time in class analysing the problem in a systematic way, and to elicit suggestions on what classroom activities might facilitate such an analysis. There were nine items, two which were limited response questions, five which were open questions, and the remaining two which were yes/no questions with the option to give further details.

From analysis of these questionnaires, it became apparent that less than half the students (in both groups) had any real awareness of negative lexical transfer. Only six students (15% of the total number) mentioned having previously looked at this problem in any systematic way, which coincided with the number claiming to have made any attempt to keep a record of these types of errors (only three of whom mentioned actually writing a word list). Interestingly, one student made the comment that he thought that only native (English) speakers would notice the transfer problem, lending weight to the point made by Amara (2015) that students in a monolingual L1 classroom would struggle to correct these errors and may even have them reinforced. However, all students expressed the opinion that it was either very useful or essential to spend time in class focusing on transfer.

Following the completion of the questionnaires, students spent about 15 minutes, in groups of four or five, discussing some of the questions featured in the questionnaires and a spokesperson from each group then summarized the opinions discussed. This summary was recorded. The main points that were highlighted were:

Greater exposure to/contact with English is needed to help eliminate errors of negative transfer.

It is natural for students to try to adapt their Spanish lexis to English if there is a gap in knowledge.

Error correction/analysis, translation activities, more writing practice, and the recording of word lists would be useful ways of addressing the issue.

Another small-group discussion session was carried out in week 7. Students worked in groups of four or five and discussed five pre-prepared questions. They were asked how appropriate they deemed the time spent in class on the project, the lexical items analysed, and the practice activities we had done. They were given the opportunity to suggest alternative ways of approaching the issue, and were asked to consider whether they now felt more aware of their own lexical transfer errors and of the issue of L1 interference in general. A spokesperson from each group then summarized the ideas of their group. This discussion was recorded. The responses were mostly positive, though students naturally expressed preferences for some activities over others. The overall impression was that they appreciated taking part in the project and valued its aims.

At the end of the project, a focus group was conducted with five students from each group. In these meetings, the students were asked their opinions on a series of questions about the project. In response to the first question about whether they thought that the activities carried out in class had helped them avoid L1 interference errors, the students were overwhelmingly positive. All the students said that the activities had helped them become more aware of these errors and many gave specific examples:

One mistake that I always made was “share time”. (Camila, L3)

In the written tasks, I still write “called my attention” and then I think, “No wait! It’s ‘caught my attention’”. (Francisco, L3)

I always said “arrive to” instead of “arrive at”. (Sofia, L3)

I always translated “dar una prueba” and “practicar un deporte” wrongly. (Andrea, CC1)

Now I am much more aware of these types of errors, and thanks to everything we have done in class, I am increasingly managing to avoid them. (Sofia, L3)

Some of the students from the fourth-year group (CC1) made the point that they had already been aware of some of the errors highlighted during the project but pointed out that they nevertheless thought that the activities had been valuable:

We were aware of the majority [of these errors] but we think in Spanish so we still make mistakes…so I think it is still worth practising them. (Soledad, CC1)

This comment reflected a general appreciation that the errors we analysed were difficult to eliminate because they had become entrenched. For example, Pablo (L3) pointed out that although he was aware of the correct versions of the lexical items, he was often unaware that the other alternative (in this case, an example of negative transfer) was not acceptable. Other comments reflected the perception students have of how important it is for them to eliminate these errors:

When we leave here and go out and get jobs, we won’t be able to make these types of mistakes, because as translators and teachers, it will affect our work. (Francisco, L3)

The students also favoured the systematic treatment of negative transfer errors over dealing with errors as they arose:

Before, when we made one of these mistakes, for example, in a writing task, it was highlighted, but we never did exercises to help us to not make the mistake again, and so we continued making them. (Soledad, CC1)

Other students expressed the view that the time spent analysing these errors, and the translation and discussion activities that we did to practise the correct forms, were helping them to avoid these errors. The point was made that simply drawing students’ attention to examples of negative lexical transfer at the moment the errors occurred would not raise awareness of the issue:

If you had only corrected these mistakes in class when we made them, and mentioned that they were examples of L1 interference, we wouldn’t have paid much attention to it. But since it became part of the class, it made it easier for us to remember them. (Camila, L3)

I also asked the students about whether they thought that the activities had raised their awareness of the general problem of negative lexical transfer. Again, the response was positive. Students from both groups claimed that they had noticed changes in the way they thought when writing and, to a lesser extent, speaking. This development was not limited to the problem of false cognates, as students also mentioned thinking more about collocation and whether or not certain combinations of words used in Spanish could be used in the same way in English.

Before now, I just sat down and wrote, and l1 interference happened, but now I take my time and think about what I have written and whether it actually comes from Spanish, and if it will be understood. This has been a turning point. (Francisco, L3)

I have realized that I think in Spanish a lot and translate Spanish to English word for word. Now I am more aware that I make certain mistakes and I ask myself, “does this combination of words work in English?” (Vicente, CC1)

We are much more careful about not making these mistakes. If we make a mistake, it is immediately going to sound wrong and we’re going to say, “No. That’s not right,” especially with the words that we have practised, but we are also more careful about not making mistakes that we haven’t seen. (Soledad, CC1)

Another noteworthy comment, which was made by a number of students, both during the mid-project group discussions and the focus group meetings, was that the activities should be included in the syllabus from year one. Francisco (L3) summed up this view:

I think that instead of being just a one-off project, this should be part of the syllabus because for us as translators and teachers, whether we like it or not, this is something essential.

Towards the end of the project, I was pleasantly surprised to receive an e-mail from one of the second-year students with further examples of possible L1 interference. When asked to tell the group about her reflections, she commented:

I had been thinking about [L1 interference] for a while, and suddenly I thought of the word realize and I said to myself, “I’m sure some people think that means realizar” and I looked it up. Then I thought of another one, which was slow motion which means cámara lenta, but people might translate it as slow camera and that would be wrong. (Claudia, L3)

I found this student’s comments very encouraging. Not only did they provide evidence that she was engaged in the issue of L1 interference and was perhaps beginning to think differently about the two languages she spoke, but also because they offered a clear example of what I, as a teacher, had wanted to achieve, which was for students to think more critically about how Spanish and English correspond and differ.

Discussion

My initial impression of how the students reacted to the activities we did during the project was that many of them were less able to identify examples of negative transfer than I had expected. Some of them seemed surprised to learn that language forms that they had assumed to be correct for many years were actually wrong. However, once they had recognized these errors as stemming from L1, and so to a certain extent “theirs”, students from both groups quickly became engaged with the issue. On the whole, students participated enthusiastically in both the teacher-led activities and the mini-presentations, which generated extended and animated discussion. Students were keen to seek clarification about correspondence and difference between L1 and L2 and they became more alert to possible instances of negative transfer. These impressions were confirmed by comments made in both focus groups.

Both the quantitative and qualitative data from this study seem to support the claim made by Nation (2001), Schmitt (2008), and Hulstijn (2001), among others, that direct focus on, and engagement with certain lexical items (in this case, those which cause problems for Chilean Spanish speakers) help learners make those items part of their usable vocabulary. Furthermore, the type of instruction carried out seems to have raised awareness of a common problem of second language learning: that of L1 interference.

It should be noted that despite the positive results of the study, some of the errors which were dealt with were still being made in instances of freer production by some students after the project. This point highlights the importance of repeated revision over the long term to ensure automaticity of recall and production.

Conclusion

When drawing conclusions about the impact of this research project, it is important to be aware of the limited nature of the study. First, it has to be acknowledged that the errors which were analysed were somewhat artificial in the sense that they were not collected from samples of free oral or written production of the students who participated in the study. Neither did the instruments used to analyse students’ knowledge of the target items incorporate free production. In addition, the qualitative data obtained from the students throughout the study were collected in the presence of the researcher, which may have influenced the answers and opinions given. Finally, it must also be observed that due to the short-term nature of the project, it was not possible to check the retention of learning over time and so the long-term impact of the instruction, discussion, and practice done in class is still questionable.

Nevertheless, the findings of the study seem to give some indication that the systematic analysis of typical examples of negative lexical transfer can, at least in the short-term, reduce the frequency of the errors being produced. They also indicate that the students generally valued the opportunity to focus on the typical lexical mistakes that they are prone to making as Spanish speakers and point to an increased awareness in the participants of the lexical pitfalls implicit in having an l1 which shares roots with the L2 being learnt.

This research project has highlighted an area of study which has hitherto been neglected or overlooked in many English language-teaching institutions. This is because course programmes in many schools, institutes, and universities are often closely tied to general English language course books which have been produced for the international market and which therefore cannot cater to local learner needs. The need to focus on the specific linguistic problems which arise in monolingual classes and to design appropriate materials for this purpose is, therefore, something which ought to be addressed by course planners, not just in Chile but in all contexts where L1 interference is a significant problem. The participants in this study were university students studying translation and English teaching degrees. They expressed the view that the fossilization of certain errors might impede the attainment of the linguistic proficiency required in their future careers. It is therefore important that lexical L1 interference be given sufficient attention.

In terms of future research, there are a number of avenues which could be explored further. A longer-term study would allow for investigation of the possible impact of this type of vocabulary instruction on L1 interference errors in free production and provide a more credible measure of improvement over the long term. Another area for exploration would be more specific research into the frequency and type of lexical transfer errors made by students of different ages and levels, and in different educational contexts, for the purpose of building and piloting a number of target lexical lists and study materials which could be incorporated into syllabuses.