Introduction

As a member of the practitioner research family, exploratory practice (EP) envisages learners as potential co-researchers of their classroom environment (Allwright, 2005; Allwright & Hanks, 2009; Hanks, 2017a). The EP literature evidences teachers and learners successfully exploiting the principles of EP, working collegially on teacher-initiated puzzles to enhance understanding of their language teaching/learning experiences (e.g., Banister, 2017; Dar, 2015; Hanks, 2015b; Perpignan, 2003; Slimani-Rolls, 2003). However, the extent to which learners can develop, explore, and set their own research agendas is less well-documented and forms the focus of this paper.

This paper describes my experience as a business English teacher-researcher working with my tertiary level learners in line with the inclusivity principle of EP (see Appendix A for the full list of EP principles), asking them to identify a language learning “puzzle” and guiding them as we aimed to enhance what Gieve and Miller (2006) refer to as “quality of life”.

This paper provides an overview of EP, drawing upon literature about puzzles and how learners can use puzzles to set research agendas and learning paths. My mixed methods approach, including my use of case studies to foreground my learners’ perspectives, is then outlined. The subsequent analysis and discussion focuses on the opportunities and challenges arising from learner puzzlement in the business English classroom. Finally, recommendations are given for teacher-researchers considering facilitation of learner puzzling.

Literature Review

This section provides an overview of EP and examines examples of puzzling by both teachers and learners. It concludes by highlighting some issues that have been identified around learner puzzling.

Exploratory Practice

The scepticism with which English language teachers view the relevance of research findings in their field has long been a cause for concern (Anwaruddin, 2016; Borg, 2009; Rainey de Díaz, 2005). EP, a form of practitioner research, has emerged as one way to address concerns around the research-pedagogy divide (Allwright, 2005; Allwright & Hanks, 2009; Hanks, 2017a). EP is a form of practitioner research which has been used by and for language teachers to seek understanding of counter-intuitive aspects of classroom life, which EP refers to as puzzles. For example, Dar (2015) wondered why her students failed to take responsibility for learning beyond the classroom and Costantino (in press) considered how she could promote learner engagement with her written feedback. Proposing “practice as research” (Hanks, 2016, p. 28), EP gets the former done whilst simultaneously doing the latter. Studies have highlighted how EP has helped teachers see their learners as legitimate co-investigators of their language learning experience (Hanks, 2015b) and the mutual benefits to be gained from EP’s integration of research and teaching via potentially exploitable pedagogic activities or PEPAs (Hanks, 2016). Thus, EP repositions the classroom at the confluence of teaching, learning, and research. This “subtly radical move” (Hanks, 2017b, p. 47) reconceives the learning space as a site not only of knowledge consumption, but also as a legitimate scene for what Allwright (2006, p. 15) calls “locally helpful understandings”.

Puzzles

Puzzles are central to EP, providing the focus of inquiry. Teachers and learners are encouraged to identify puzzles in their classroom contexts and explore them, striving primarily towards understanding to boost quality of life in their local, idiosyncratic settings (Allwright & Hanks, 2009). EP prefers the word “puzzle” (and extended forms to puzzle, puzzling, and puzzlement). This preference reflects a rejection of problem-solution paradigms over an emphasis on the quest for understanding of practitioners’ language teaching or learning experiences.

Hanks (2015a) links learner puzzling to a Freirean pedagogy with its sense of empowerment. She explains that seeing phenonema as puzzles rather than problems is essentially a matter of adopting a different mind-set (Hanks, 2017a). However, a precise definition of a puzzle and how puzzles differ from problems fail to emerge clearly from the literature. Slimani-Rolls and Kiely (in press) note the difficulty that novice teacher-researchers may have in distinguishing between puzzles and problems. Grappling with this elusive puzzle-problem distinction, Dar (2015) contends that “not all puzzles are problematic” (p. 51) and, indeed, the literature does include examples of positively framed puzzles such as Goral’s (in press) “Why do discussion boards work so well?” or Hanks’ (2015a) student, who puzzled: “Why do people learn bad words = swear words more easily?” Admittedly, negatively framed puzzles, which more closely resemble problems, are more prominent in the EP literature.

Teacher Puzzles

Teacher-researchers have heeded EP’s call to explore their own teaching puzzles. Numerous studies attest the resulting positive impact of EP on classroom quality of life (e.g., Banister, 2017; Costantino, in press; Dar, 2015; Perpignan, 2003). In addition, Slimani-Rolls and Kiely’s (forthcoming) volume acknowledges the value of teacher puzzlement for continuing professional development. In the studies above, learners were empowered as co-researchers to explore their teachers’ puzzles. However, EP proposes that learners formulate and explore their own puzzles. In contrast to the studies focusing on teacher puzzles (listed in the Exploratory Practice section of this literature review), the literature on learner-initiated puzzles is sparse. Four such studies are drawn upon below.

Learner Puzzles

Chu’s (2007) study described her experience working with fifth grade school learners on UK study skills courses. Her learners explored their own puzzles over five months and Chu found they welcomed how puzzling allowed them to exercise decision-making power in their learning (Chu, 2007). Chu’s learners wrote reflective journals and discussed their puzzles to better understand classroom life. Chu cited initial concerns about learners’ expectations of responsibility but concluded that having a puzzle promoted active engagement with learning (Chu, 2007).

Dawson’s (2017) account draws upon learners at a private language school in the UK preparing for academic study and IELTS assessment. She noted that learners’ potential as productive puzzlers of their own learning can be viewed against the backdrop of learner autonomy and empowerment (Dawson, 2017). She concluded that the understandings learners gained through puzzle exploration lacked depth. Yet she saw value in the process itself which she claims illuminated her own teaching puzzle about the attractiveness for students of solution-based approaches. She also observed her learners becoming increasingly independent and confident as they embraced new working modes such as teamwork (Dawson, 2017). Learners reported that puzzling promoted classroom collaboration and boosted confidence in language use (Dawson, 2017).

Hanks’ twin studies (2015a and 2017b) examined learner perspectives and experiences of EP in a UK pre-sessional English for academic purposes (EAP) context. Her 2015 study described how learners enjoyed the exploration of a question to which the answer was unknown but understanding of which appeared directly relevant, set as it was, by learners themselves (Hanks, 2015a). Hanks’ (2017b) study detailed the opportunities and challenges of an EP approach and process for neophyte practitioner-researchers. Hanks concluded that EP’s base in the participants’ lived experience makes it “entirely relevant” for EAP practitioners (both teachers and learners), representing a potential path towards true inclusivity in the research endeavour (Hanks, 2017b).

Taken collectively, the studies by Chu (2007), Hanks (2015a, 2017b) and Dawson (2017) offer grounds for optimism for practitioners looking to scaffold learner puzzling in other localised contexts. However, a number of issues were also highlighted by these studies which warrant closer attention.

Challenges Around Learner Puzzlement

Firstly, there is the practical implementation of learner puzzlement. As Dawson (2017) notes, there is no single method of implementing learner puzzling. However, the studies described above all moved systematically from learners first identifying puzzles, then reflecting and reformulating whilst concurrently exploring as they strove towards understanding. Yet the extent to which a teacher can or should guide learners as they attempt to set their own research agendas remains unclear. Teacher-researchers might worry that too much scaffolding could invalidate the process but too little might see it peter out.

Secondly, there is the time factor. Hanks (2017b) and Chu (2007) were both fortunate to have syllabuses which could accommodate an extensive EP component. It remains to be seen how learner puzzling would fare in a syllabus with less space for the extended project work that Hanks (2017b) and Dawson (2017) organised. A further temporal aspect of learner puzzling relates to the extent to which understanding of learners’ language learning experiences continues beyond the formal period of puzzling. Dawson suggests that it was only some weeks after their course finished that her learners started to recognise the greater sense of confidence that learner puzzling had provided (Dawson, 2017).

The literature raises a third issue. Some learner-researchers in Dawson’s (2017) account noted that learner puzzling was sometimes seen as an unwelcome distraction from their main aim, namely, exam practice. Hanks (2015a, 2017b) noted similar learner resistance and this goes to the heart of concerns about implementing EP. Whilst Hanks’ (2015a) study reported that the success of puzzling was rooted in its direct relevance to learners’ lives, the participants in some of her studies were “specialized groups” (Hanks, 2017b, p. 40), some of whom were, in fact, language teachers themselves and might be viewed as positively predisposed to puzzling about language teaching/learning experiences. In addition, the learners in Hanks’ (2017b) case study were on pre-sessional EAP courses preparing for undergraduate study. These learners may have had more time to puzzle than undergraduate learners immersed in their studies and with all the associated stresses and strains of university life to contend with.

Finally, learner puzzlers in all four studies found the puzzle-problem distinction problematic. The focus of the learner-researchers often coalesced around problem-solving rather than prioritising understanding of their language learning experiences and represented a move away from the intended aim of puzzling. Dawson (2017) related how her learners found it a challenge to move away from a solution-based mind-set. She concluded that the understandings her learners gained through puzzle exploration lacked depth but hints that the process of facilitating learner puzzling helped advance her understanding of learners’ fixation on problem-solution paradigms. Hanks (2017b) has also identified learners’ apparent fixation with solutions as an area of difficulty and connects it to the temporal issues outlined previously, stating that a:

challenge for implementing EP, then, is to successfully convey the importance of puzzling, and to give enough time for a question framed as a “problem” to transmute into genuine puzzled curiosity. There is a fine distinction between a problem (requiring remedial action) and puzzlement (a cognitive challenge), which merits further investigation. (Hanks, 2017b, p. 48)

While Hanks (2017a, 2017b) prefers to distinguish between “seeing” something as a puzzle rather than a problem, Chu (2007) points out that a solution can be seen as a form of understanding. Meanwhile, as Dawson’s (2017) learners wrestled with puzzles that might prove a challenge even for language teachers, Hanks (2017b), by contrast, reported that her learners enjoyed tackling puzzles that exposed genuinely counter-intuitive phenomena and cites this as a perceived strength of the EP process.

To summarise, there is a broad acknowledgement in the existing literature on learner puzzling that it is far from straightforward to introduce and implement in the language classroom. Hanks (2017b) suggests that future studies situated in different language learning settings could illuminate the challenges and related to learners setting their own research agendas through puzzling. The present study takes up this call by providing an account of a teacher-researcher supporting learner puzzlement in a different context: a business English course for undergraduate exchange students in the UK. These learners were concurrently studying on business programmes. As such, this represented a highly time pressured context and one which heightened the challenges around the facilitation of learner puzzlement.

Research Focus

My previous experience of exploring teacher puzzles via EP had proved rewarding, boosting my teacher self-efficacy (Banister, 2016) and instilling a sense that my learners could potentially set and explore their own research agendas. Facilitation of learner puzzling presented a further opportunity to gauge the extent to which this conception of learners was grounded in reality. At the same time, it had the potential to promote a culture of curiosity, the prospect of which prompted the following questions to frame this research:

What kind of puzzles would learners be interested in?

What, if any, benefits would accrue from learner puzzling?

What, if any, aspects of learner puzzling would prove challenging?

In line with EP’s principle of exploration for understanding, these three research questions also imply a focus on underlying notions of “Why?” Moreover, the undergraduate level business English context represents a new setting within which learner puzzling could play out.

Method

This section describes my participants and the setting for this research. Subsequently, the data collection procedures and tools of analysis used are laid out but this section starts with a focus on some ethical considerations for the study.

Ethical Issues

EP foregrounds ethical aspects by attempting to redress the balance between the researcher and the researched (Allwright, 2005), giving the latter greater agency in the process. However, my previous experiences of engaging with EP and its core principles highlighted the need to avoid imposing an unacceptably heavy workload on participants. This therefore informed my approach as I followed Hanks’ (2017b) advice to reframe sessions rather than replace them when looking for ways to integrate learner puzzling into my already busy business English syllabus. Moreover, care was taken to select business-related content that could both promote learner puzzling yet maintain a clear business focus on sessions.

In addition to these ethical challenges around the research framework, the institution’s ethical procedures were also carefully followed. Participants were informed of both the nature and the aims of the research process via an in-class presentation and consent forms that were distributed at the outset. Anonymity was preserved in writing up the research and data stored securely.

Participants: My Learners and Me

The participants were 14 (8 in the autumn 2016 cohort and 6 in spring 2017) 3rd year undergraduate exchange students at a UK university. All participants were studying for business degrees and had elected to take a business English module as part of their exchange in the UK. The students were all at an advanced English language proficiency level. The two cohorts (autumn 2016 and spring 2017) represented a range of L1 backgrounds including Chinese and Slavic languages but these three Latin-based languages, French, Spanish, and Italian, predominated. As a teacher-researcher striving to understand how EP might promote learner puzzlement and how learners could be supported in the process, I was also very much a participant in this research, and inevitably brought my own experiences of EP to the process. My earlier teacher puzzles explored why it was a challenge to obtain meaningful learner feedback and evaluations (Banister, 2016) and learners’ decision-making when peer teaching vocabulary (Banister, 2017).

Teaching, Learning, and Research Context

Our module, Advanced Business English for Exchange Students (B6 henceforth), incorporates 36 classroom contact hours over a twelve-week semester and focuses on both language (business English) and content (business). B6 aims to develop learners’ business English skills and boost employability. Written genres such as business reports and spoken genres such as oral presentations form an important part of the course. The module covers business topics such as finance, entrepreneurship, and branding. Language (grammar, lexis, pronunciation, and style) development is based on learners’ in-class and written discussions of business news issues. Learners are assessed on their ability to communicate to business audiences and through a final written report on a business topic selected earlier by learners themselves.

Data Collection: Research as Practice

EP envisages that research gets done at the same time as teaching and learning (Allwright, 2005; Allwright & Hanks, 2009; Hanks, 2017a). PEPAs are proposed as a means to unobtrusively explore puzzles and therefore, the familiar language classroom activities were utilised. Whilst B6 learners do engage, often enthusiastically, with the language learning aims of the module, they typically expect a very clear business frame for any language work; and from the outset of the research, I was mindful that anything which could not be linked in some way with the business context might prove incompatible with learners’ expectations. With their prioritisation of business, it was unclear whether my learners would be willing to engage with language learning puzzles. This made it of the utmost importance from the beginning that learners saw puzzling as integrated into the curriculum and not a superfluous add-on.

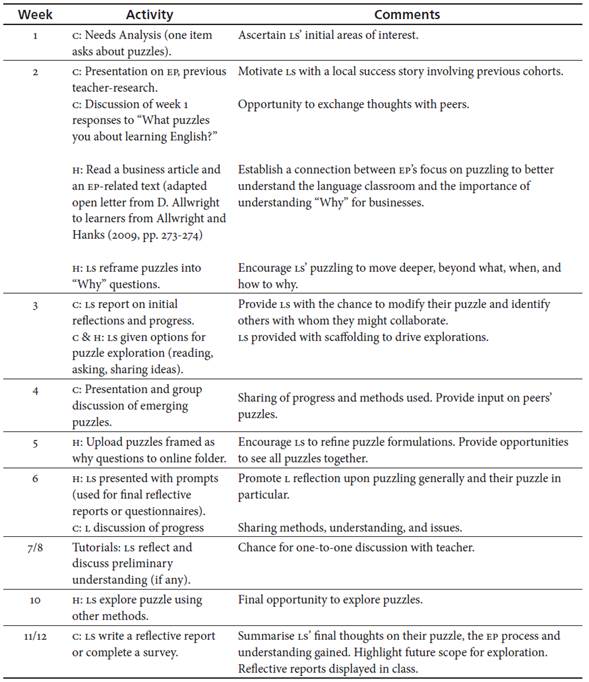

In the previous EP research I had conducted around my teacher puzzles, I had enjoyed designing PEPAs that shed light on my teacher puzzle. However, in this present study my teacher’s role was very different. Instead of looking for ways to explore my own puzzle, the focus was on guiding my learners in exploration of their own research agendas. I recognised the need to provide all learners with opportunities to explore their puzzles. Recognising that our busy syllabus called for a compact enactment of EP, I prepared classroom and homework tasks designed to foreground reflection, discussion, and sharing of understanding whilst still leaving learners the agency to work with puzzles in a way that suited them. As Chu (2007) notes, teachers can stimulate and motivate their learners by giving them decision-making power. The activities used, which also form the basis of data collection for this study, are summarised in Appendix B.

Procedure

I introduced the concept of a puzzle in week one. This was done via a single question on a standard needs analysis form (NA) which asked learners what puzzled them about learning English and business English in particular. This was to gauge learners’ areas of interest early on and help me as a facilitator of puzzling. The inclusion on the NA of this question was also an attempt to locate puzzling within the wider context of learners’ past, present, and future language needs. In week two I presented an overview of EP, outlined its principles with examples of teacher and learner. I had a teacher puzzle of my own but intentionally held this back until week three to avoid influencing learners’ own choice of puzzles. It was important for me as the teacher to have a puzzle to explore my own classroom experience but also to project a sense of solidarity. In other words, I hoped that this demonstration of aspects of classroom life remaining elusive to their teacher might legitimise puzzling for my learners. I further hoped it might help overcome any reluctance about revealing weaknesses to peers, and, of course, the teacher who would later be assessing their English. The understanding gained from exploration of this puzzle can be found elsewhere (Banister, 2017) but lies beyond the scope of this paper. In the following weeks, learners were given a series of in-class and homework tasks to facilitate refinement and exploration of their puzzles and develop their research agendas. Some activities involved individual work but there was scope for and promotion of peer-sharing and discussion (Appendix B). As noted previously, there is no prescribed procedure for working with learner puzzles but the procedure outlined above broadly aligns with implementations by Chu (2007), Hanks (2015a, 2017b), and Dawson (2017).

The intention at the start of the process was to capture learners’ thoughts at multiple points. As a busy teacher, I preferred to collect written data as it is less time-consuming to analyse. For the autumn 2016 cohort, I captured learners’ summarising thoughts through written reflective reports and in spring 2017 used the same questions reformatted as open-ended questionnaires (see Appendix C for these reflective report/questionnaire items). I supplemented this data with observations of my learners as they worked on the PEPAs and recorded these in my teacher reflective journal. In this journal I also recorded learners’ thoughts about their puzzles which emerged from in-class discussions and ad-hoc learner comments. Individual mid-module tutorials yielded further data to record in my reflective journal. Additional language learning artefacts such as NA forms, tutorial record forms, and a dedicated learner puzzle folder in our online learning space were also utilised.

It should be reiterated that all the PEPAs were activities that learners would normally undertake as part of B6. They did not intrude (see EP principle 7, Appendix A) and learners were required to practise their English language skills whilst undertaking them. For instance, learners were reminded to practise “signpost” language when giving the mini-presentations in week 4. Similarly, delayed language-related feedback was provided after discussions of puzzles and learners were encouraged to read peers’ written reflective reports in a low-key end-of-module dissemination stage.

Data Analysis

The procedure outlined above and the inclusion of questionnaires and surveys yielded data suitable for quantitative analysis. However, EP’s focus on human aspects such as quality of life and the modest size of the learner cohorts lent itself to qualitative analyses. Three learners were selected for the case studies presented in this paper. They came from a range of first language backgrounds (Czech, Cantonese, and French) and nationality (Czech, Chinese, and French-Canadian, respectively). Selection was partly on the basis of these learners providing the fullest datasets (attended class regularly, participating in the puzzle-related activities completing the end of module questionnaires/reflective reports). One learner, Pierre, was selected in an attempt to foreground a more critical voice on learner puzzling. In my analysis of open-ended responses to surveys, reflective reports, and reflective journal entries, I used manual coding to stay close to my qualitative data and identify prominent themes in the dataset. Collaboration with teacher-researchers from my institute enabled an exchange of materials and ideas. A colleague from my extended professional network provided an outsider perspective on facilitation of learner puzzling via EP principles which further informed data analysis and interpretation. Note that in the subsequent reporting, B6 2016 denotes an autumn 2016 learner and B6 2017 a spring 2017 learner.

Findings and Understanding

In this section I present my analysis, referred to here as “Understanding” in line with EP’s principles. I start by examining the nature of my learners’ puzzles before moving on to foreground learners’ perspectives on the process of puzzling, utilising the three case studies and drawing upon supplementary data from other learners.

Focus and Nature of Learner Puzzles

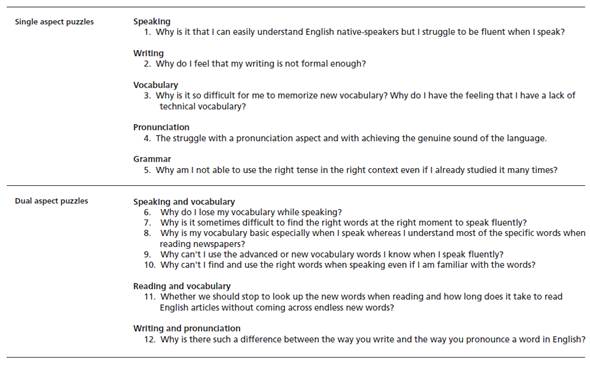

My first research question was: “What kind of puzzles would learners be interested in?” This can be addressed in terms of the focus and the nature of their puzzles. Of the 14 participants, 12 students participated in and completed the vast majority of PEPAs designed to scaffold puzzle exploration. In the autumn 2016 cohort of eight students, seven out of eight wrote a summarising reflective report. Due to a timetable issue, only two out of six spring 2017 learners completed the summative questionnaire. Whilst this was disappointing, until this point, high engagement levels with PEPAs in class were observed and the additional classroom artefacts supplemented my teacher-researcher reflections. Of the 14 learners across the two cohorts, 12 learners each formulated one puzzle in relation to their English language learning experiences. Learners’ puzzles gravitated towards vocabulary, speaking, and pronunciation and, overall, speaking emerged as the most puzzled aspect. However, beyond these popular areas, puzzlement also covered formality in written production, and tense usage. Learners’ puzzles are listed in Figure 1 with their final iterations/wording retained for the sake of authenticity.

The majority of learner puzzles (7/12) were multifaceted, demonstrating awareness of how multiple aspects of language learning might impact each other. For example, vocabulary and speaking were linked in five puzzles (6-10). When single aspect puzzles are considered alongside dual aspect puzzles, speaking and vocabulary feature most prominently (on 6 occasions in both cases).

Nine respondents gave reasons for their choice of puzzle in the questionnaire and reflective reports with a problem-based approach evident in eight out of nine cases. A linguistic analysis of this data allows the identification of three significant sub-themes (note that some responses mentioned two of the following sub-themes hence, the total number of instances exceeds the 9 respondents).

Negative affect (6 instances): “endless”, “struggle/s”, “frustrates”, “frustration”, “embarrassment”, “deepest concern”.

Inadequacy/inability (4 instances): “a lack of”, “unable to”, “not enough”, “don’t remember”.

Complexity (3 instances): “difficult”, “prevents”, “basic”.

Only one learner took a different outlook, framing their puzzle selection more positively and explaining that it would prove “useful to communicate in a proper way” (B6 2017 learner).

Despite the negative framing, overall, learners’ reactions to having a puzzle were largely positive. Of the nine students who completed the reflective report or questionnaire, eight addressed the question: Do you think that having a puzzle is a useful component to this module? Why? Of these nine students eight stated that they felt puzzles were useful. When asked why they felt positive about puzzling, learners cited the chance to work on understanding something specific to their individual situation, noting that puzzling “allows to focus on a personal issue” and “it has definitely been interesting to explore it” (B6 2017 learners). While the vast majority of learners found puzzling to be a positive experience, one learner was less enthusiastic. I now present the experience and perspectives of three learners, two who were more positive, and in the interests of balance and a more critical discussion, that of the learner less enthusiastic about puzzling. Pseudonyms are used below.

Case Studies

Naomi’s Perspective

Naomi, from Hong Kong, puzzled about encountering new lexis when reading. She enjoyed charting her fluency in reading but wondered how native speakers coped when they must “have experienced the same process and how come they ended up so differently?” Expressed like this, Naomi seems close to the sense of wonderment that Hanks (2017a) hopes EP can cultivate. Naomi was overburdened with new words when she started to read business related texts and found this a barrier to her reading. Naomi reflected on how she had tried memorising lists of words but found it “inefficient and tedious”. She then sourced an article that suggested graded readers and was pleased with its positive impact on her reading fluency: “It did help!” However, she later returned to business articles, wrestling with these and experiencing a setback: “Everything became frustrating again . . . I was so tortured . . . and didn’t want to let a new word go.” Finally, a mentor and work colleague shared shorter finance related articles via a WhatsApp group, which resulted in a satisfying equilibrium: “I read articles there every morning…which does not take me a long time while buffing up my vocabulary day by day!” Naomi concluded that having a puzzle was useful because “it engages us . . . and helps us to excel.”

Janice’s Perspective

Meanwhile, Janice, a Czech learner puzzled about why she struggled to pronounce the sounds of English, “the genuine sound of the language”. She showed early awareness of the physiological differences between her native tongue and English when it came to accurate oral production. Reflecting on the process, Janice said that she reaped the benefits early on in the process:

I believe just formulating my puzzle actually did help me a lot. Since then I was focusing consciously on a way people-especially native speakers-talk, to be honest not only the sounds but also the stresses and pace of their speeches.

She explained her methods as she researched her puzzle: How she overcame her embarrassment to ask people for help during conversation and how she used phonetic symbols to record problematic pronunciation. In addition, she listened to English via audio-books and online TV. After a class activity in which learners had acted as TV commentators for partners who had their backs to the screen (with the audio off), Janice linked this to her puzzle and understood that she might focus more effectively on pronunciation features without the distraction of the images. However, she also came to understand that fossilised mispronunciation was difficult to shift: “The only thing I can do is to hope that when I correct myself for the thousandth time, I will eventually remember.”

Pierre’s Perspective

By contrast with Naomi and Janice, Pierre’s perspective on puzzling was more critical and he seems to have found puzzling less worthwhile. A native speaker of French, Pierre puzzled about why he struggled to achieve fluency in spoken English despite being able to understand native speakers with relative ease. Pierre’s reaction in the first class was interesting. As I introduced learners to the concept of puzzles and related it to the world of business, he asked: “Where exactly are we going with this Chris?” an early indication that he might be resistant to setting his own research agenda. Despite indicating in his reflective report that his puzzle represented a deep concern, he was not able to describe any methods he had used to research this puzzle other than personal reflection. This, coupled with his relative lack of enthusiasm when we undertook the PEPAs in class, hinted that he found puzzling a waste of time. This was confirmed when he said that puzzles were useful but on the condition that “it helps the student in the end” and his somewhat depressing final admission that “In the end, I don’t know why we did this really.”

These three learner perspectives provide a snapshot of learner puzzling in a business English classroom. In the following discussion section, the cases above and additional learners’ voices are interwoven with my own reflections and observations from my privileged insider perspective.

Discussion

Opportunities: Positive Connection-Making

My second research question focused on the potential advantages of getting learners to set their own research agendas: “What, if any, benefits would accrue from learner puzzling?”

My experience scaffolding learner puzzling chimed with that of Perpignan (2003), who recognised that rather than the understanding gained, it is often in the exploration itself where real value resides. In other words, quality of classroom life is best understood as a process rather than product (Gieve & Miller, 2006). For example, in the present study, having and exploring a puzzle in a business English context also seemed to prompt some positive connection-making by learners within their wider lived experience. This was achieved through finding a business connection, a connection with pedagogy or with their exchange experience. Naomi’s case demonstrates that through the linking of her puzzle to her business interest (finance articles), she was able to ensure that it stayed directly relevant, which proponents of EP (Hanks, 2017b) claim as one of the key advantages of puzzling via EP principles.

Other kinds of positive linkage emerged from learner puzzling. Janice used her puzzle to make connections to her native language and her past language learning experiences. In fact, she also linked pedagogic activities to her puzzle to gain greater understanding. Janice concluded that her listening skill might best be developed through audio-only exposure to listening texts (as opposed to audio plus images). Janice made a link to a class activity in which students had listened to an excerpt from a TV show without seeing the related images. Similarly, another B6 learner mentioned in her reflective report that after puzzling she now realised that vocabulary knowledge is not always reflected in spoken production. This student concluded that she should make a conscious effort to incorporate recently seen words into written and spoken language production. This example reveals how puzzles can highlight the potential usefulness of language learning strategies; encouraging learner buy-in to suggestions made by teachers or published materials.

A common thread in learners’ puzzles was a focus on oral production of the language (in 6/12 puzzles). Learners especially linked speaking and vocabulary knowledge. This preoccupation with oral skills comes as little surprise. My learners’ focus on speaking skills perhaps reflects their desire to survive their sudden immersion in a new academic and social environment. Another learner, whose puzzle revolved around a lack of vocabulary, related how a shopping trip prompted her puzzle:

I was interested in this…because…when I moved to London, I need to go and buy some pots, cutlery, plates…It was horrible to find the specific names of each pot…I just felt embarrassed because of my lack of vocabulary. (B6 2016)

If puzzles can draw upon learners’ wider lived experiences, even negative experiences, and bring these into the classroom, it might aid learners in setting their own research agendas, learning goals and paths, and sustaining their search for understanding.

Challenges: Puzzlement Mind-sets and Tensions in Facilitation of Puzzling

My third and final research question considered the difficulties that might arise: “What, if any, aspects of learner puzzling would prove challenging?” My learners all focused on problematic aspects (inadequacies, complexities, and negative affect) and spent considerable time focused on a negative aspect of classroom life. This mirrored the findings from previous studies exhibiting similar tendencies (Chu, 2007; Hanks, 2017b). As many business English materials follow an action-oriented business case study approach, it might be tentatively suggested that learners found it difficult to move from this paradigm on their business modules (where they were concurrently studying) when asked to prioritise understanding of their language learning experiences ahead of a need for action. Despite this, Janice and Naomi’s statements show progression in the search for understanding of their puzzles.

The problem-solution gravitation points to a tension in EP though: Having already decided to shape learners’ puzzles into a “Why?” frame, I found myself reluctant to interfere further by insisting that they turn a negative into a positive frame. The broader issue lies in the extent to which the teacher-researcher facilitating puzzles can or should legitimately influence learners’ puzzles before, at some point, the puzzle ceases to be truly owned by the learners themselves. That said, my learners stated in tutorials and class discussion that they felt under no pressure to find solutions and many students mentioned why this might be unrealistic given our limited timeframe. Learners recognised that their puzzles would require further exploration, which some learners indicated they were willing to consider.

It is easy to forget the challenge that a researcher role entails for learners and a further tension in the puzzle facilitation process relates to how teacher-researchers communicate the purpose of learner puzzling. Pierre, the least enthusiastic about having a puzzle, later stated that he had thought his puzzle was more to help me with my research than something likely to be of benefit to him. I had introduced EP in the context of my own positive experiences of puzzling, partly in an attempt to build solidarity with my learners, yet Pierre’s comments allude to a perceived lack of ownership of the research process, despite my repeated reminders of his agency. They also point to the potential confusion that may result from EP’s relatively non-prescriptive and open-ended approach. If the purpose of learners’ puzzling is not successfully conveyed, the teacher’s privileged, insider position in the EP process is threatened and the whole process potentially compromised. Thus, communicating the aims of learner puzzlement and the role of both teacher-researchers and learner-researchers within EP requires careful and considered presentation on the part of the facilitator of puzzling.

Conclusion

The questionnaire and reflective report responses of my business English learners in this study revealed that a majority engaged positively with EP and in particular the aspect of learner puzzling. Whilst a small minority of learners approached puzzling with less enthusiasm, the vast majority of them successfully identified, formulated and to some extent, explored a puzzle, gaining some understanding and building some useful connections between their wider lived experience and their current context of study. There remain some notable challenges and unresolved tensions for the teacher-researcher looking to promote learner puzzling. These include encouraging a mind-set shift from puzzling to problem-solving in learner-researchers which could in turn help prioritise learners gaining a genuine, in-depth understanding of language learning experience rather than a more mechanical problem-solving. Persuading sceptical learners that setting their own research agenda is something that they can genuinely own and benefit from is a further challenge. Moreover, the level of input and guidance in the process of setting and exploring learner puzzles that teacher-researchers should or need to offer remains opaque. However, the example provided by these learners of business English suggests that those who can establish links between their English language puzzles and aspects of their wider world (e.g., exchange student status, business interests) are more likely to see their puzzle given life and injected with the relevance required to sustain their search for understanding over the course of the 12-week module and scaffolding by teacher-researchers.

Implications

Teacher-researchers looking to work on developing learner puzzles and develop learner-researcher identities in their language classrooms might wish to consider the following points. Firstly, to facilitate the positive connection-making that some learners in this study experienced at the outset, learners could be provided with a bank of PEPAs aimed at supporting their research journey. In order to maintain learners’ sense of ownership of their puzzles and avoid a prescriptive approach creeping in, learners could then be free to select tasks that they feel might illuminate their puzzle and to add additional novel tasks of their own. If the tasks were logged they could then prompt a later discussion in class in which learners explained which tasks they found best illuminated their puzzle and why. The list could feature tasks aimed at inducing positive connection-building between learners’ puzzles and their current or future business interests and/or their exchange study period in the UK. Throughout the inquiry process learners should be encouraged to share their explorations with each other. In doing so, a sense of solidarity could be fostered and classmates might be able to shed light on puzzles of their fellow learner-researchers. Learners might be able to head off negative feelings arising when puzzling is difficult. Similarly, they could support each other and help each other regain momentum when puzzling proves challenging.

Secondly, teachers hoping to scaffold learner puzzlement in business English contexts could helpfully unpack not only the similarities to be found between business study and EP principles (e.g., the power of understanding “why?”) but also the potential differences. This might help learners distinguish between the problem-solving emphasis common in business which may jar with the notion of prioritising puzzlement required of learner-researchers. Equally, this distinction must be clear in the mind of teacher-researchers aiming to scaffold the setting of learner research agendas. Understanding of these issues and tensions represents a useful starting point for teacher-researchers wishing to facilitate learner puzzlement through the adoption of EP principles, especially those who are trying to convey the notion and benefits of puzzling to undergraduate learners of business English.