Introduction

Listening fluency is a fundamental component to understand aural language and to become successful speakers, particularly, in English as a foreign language (EFL) education where exposure and practice is limited to academic or self-study practice. In this regard, Iwanaka (2014), Chang and Millett (2014), and Andrade (2006) express that this ability encouraged students to acquire not only the language but also the opportunity to expand their thoughts, culture, and communicative competences. Rost (1991) and Kim and Maeng (2012) suggest that listening fluency was a decisive competence to promote learners with capabilities such as becoming better listeners, improving oral interaction, and creating opportunities to be more analytical, synthetic, and keen on what other people say. According to Richards (2008) “listening fluency has become a goal for speaking courses because learners attempt real communication despite limited proficiency in English” (p. 2). In practice, listening fluency helps EFL students to effectively interact with the content and context of a spoken message, either face-two-face conversations or audio-visual recordings. However, most of the pre-intermediate EFL learners who were taking an English course in an EFL program of a public university in Florencia (Colombia) presented serious problems in this skill. The students misunderstood and misinterpreted oral messages from audio-visual materials such as radio podcasts, TV series, and daily-life conversations. They were unable to recognize the general content of the materials or the conversation, made incorrect guessing and analysis of the main points of the oral messages and ineffectively identified what the conversations were about. In addition, students encountered difficulties to refer to the aural materials or conversations orally because it was hard for them to remember the specific and main ideas of the conversations or to analyzed the speakers’ intentions and to connect those ideas to their life, interests, and previous knowledge. There were some reasons that affected these students.

First, students’ previous EFL education process was carried out following traditional teaching and learning methodologies to develop this ability. Some of the strategies used to practice listening were: asking for specific details, discriminating linguistics features of the language such as grammar, recognizing stressed syllables or vocabulary without integrating those elements into meaningful oral tasks. Second, in spite of the growing number of mobile apps, software, and Internet websites in which the students could practice listening, the students suggest that they did not use them to rehearse or engage in home study. Most of them have been educated by teacher-centered classes, which diminishes active student participation and interaction.

Based on the difficulties above described, we decided to conduct an action research study in which ten meaningful oral tasks were designed and implemented as a pedagogical intervention; the aim was: to systematically examine if these assignments may promote listening fluency in ten pre-intermediate EFL learners of the ELT program at the Universidad de la Amazonia in Florencia (Colombia). In addition, the implementation was carried out to try to draw some implications for using meaningful oral tasks to create opportunities to practice both listening and speaking. This research is also conducted to provide a systematic interpretation of the roles of real oral assignments to reinforce and increase learners’ performance in the listening assignments and to ascertain the effectiveness of this methodology to enhance English language learning in general.

Theoretical Framework

Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT)

According to Sarani, Behtash, and Arani (2014), TBLT increases the mastery of any language skill by creating language assignments to focus on language use rather than its form. Ellis (2003), Nunan (2004), and Richards and Rodgers (2001) agree TBLT is a teaching method that offers a framework in which students may improve their language competence by designing, implementing, and evaluating a task. In this respect, Willis and Willis (2001) and Izadpanah (2010) suggest that TBLT consists of an integrated set of processes that involves designing a task that includes decision-making. Córdoba Zúñiga (2016) concludes that meaningful oral assignments may help students to integrate any language skill and to advance in language learning. Day and Bamford (1999) indicate that these tasks may enrich the EFL learning process by providing students with productive activities that demand decision making. The second reason why students presented those difficulties was the types of activities they used to develop. The activities were uninteresting, decontextualized, and did not follow any process. According to Peachey (2011) listening fluency should be taught as a process that includes pre, while, and post listening phases. In sum, TBLT may be a significant teaching and learning methodology that could offer students opportunities to be engaged in meaningful and goal-oriented tasks to enhance fluency and accuracy at the same time. Referring to task, Nunan (2004) expresses that

A task is a piece of classroom work that involves learners in comprehending, manipulating, producing or interacting in the target language while their attention was focused on mobilizing their grammatical knowledge in order to express meaning, and in which the intention is to convey meaning rather than to manipulate form. (p. 4)

Sánchez (2009) points out that tasks are activities that promote meaningful language learning experiences for the learners.

On the other hand, Ellis (2005) manifests that fluency is the capacity to communicate in real time and accuracy is the “ability to use the target language according to its norms” (p. 142). Nunan (2006) states that “meaningful tasks provided opportunities for learners to experiment with and explore the language through learning activities which are designed to engage students in the authentic, practical and functional use of language for meaningful purposes” (p. 13). In the same respect, Ganta (2015) explains that meaningful tasks aimed at “meaning-focused language use” so they gave the participants the chance to be “language users” rather than “language learners” (p. 2761). As can be seen, there are three main components to integrate TBLT in the EFL classes: the tasks, the real-life words assignments, and the meaningful use of the language.

Willis (1996) and Ellis (2003) express that a lesson based on this methodology consists of three states: pre, during, and post task. The pre-task phase is about planning how the task will be developed by the students, the during task stage focuses on the development of the assignments, and the last stage, the post task, deals with recommendations or follow-up assignments based on the performance of the students. In this action study, we have decided to follow this model because this model offered a clear cycle in which students could have the opportunity to practice listening meaningfully.

Listening Tasks

Renukadevi (2014) recognizes that “listening tasks were fundamental to improve language competence in an EFL language” (p. 61). These assignments allow the students to expand their expertise in the language through developing activities. Kim (2004), Holden (2008), and Jin (2002) say that listening tasks are vital to help students to become experts in understanding aural language. In addition, Kim and Maeng (2012) and Benson and Voller (1997) believe that fluency tasks expose students to different aural target language input until they successfully comprehend the message. This method provides comprehensible input that encourages learners to comprehend messages, expand their experience, and actively participate in conversations. Sharma (2011) considers that listening tasks focus on three processes: comprehending, retaining, and responding. Comprehending means analyzing, understanding, and connecting what the speakers are saying to synthesize the information; retaining refers to the ability to remember and connect the messages to their prior knowledge; and responding is the way in which the knowledge acquired from the listening will be presented.

How to Promote Listening Tasks

Peachey (2011) proposes three stages: pre-listening, while listening, and post listening to implement listening tasks and these stages are related to the TBLT methodology. The pre-listening includes some activities such as setting up the activities, giving time to the students to review the instructions, and answering possible questions about the assignment. Vandergrift and Goh (2012) assume that “pre-listening engaged learners in preparatory activities that enabled them to use their background knowledge for the topic during listening” (p. 24). The while listening step is for students to listen and present the task. However, in this research, learners are asked to interact with their classmates by asking and answering questions and exchanging points of view. The final step serves to provide recommendations or to assign follow-up tasks that could solve the problems detected in the presentation of the assignments.

From our perspective, the previous cycle may promote listening tasks for various reasons. First, the stages are a dynamic process in which students have the possibility to use their previous knowledge to understand the speakers’ intentions, content, and context. Similarly, the students are exposed to a variety of listening activities that encourage practice and preparation to report their understanding. In this regard, Harmer (2008) believes that “applying different listening stages helped students prepare to listen and encouraged them to respond to the content, not just to the language, and exploit listening texts to the full” (p. 135). We also consider the previous listening plan would be a good methodology to enhance listening fluency and oral communication at the same time.

Historically, listening has been taught using both bottom-up and top-down as the main approaches. Vandergrift and Goh (2012) specify that “top-down involved the application of context and prior knowledge to interpret the message. Knowledge of the context of the listening event or the topic of a listening text to activate a conceptual framework is used to understand the message” (p. 36). However, S. Brown (2006) argues that “students need both bottom-up and top-down in listening tasks” (p. 7). Bottom-up processing helps students to connect and interpret what they listen to, and top-down allows students to use their background to understand the audios. In fact, we accept that both processes were important to encourage listening skills. In accordance with H. D. Brown (2001), interactive listening assignments are authentic tasks that are prepared to be integrated in communicative interchange. The author states that “these activities are reactive, intensive, responsive, selective and extensive assignments” (p. 258). Interactive listening tasks help to conduct real-life tasks where learners not only studied the linguistic part of the language or used the background to interpret a message, but also used their native language, the responses of their classmates, informal talks, oral interaction, or meaningful situations to make decisions to fully show that they have successfully comprehended the spoken language.

On the other hand, Lampert (1985) shows that “these techniques offer multiple opportunities to practice listening” (p. 183). That is why he proposes anticipating content, inferring, guessing, and recognizing and encouraging meaningful oral interaction as some techniques to foster listening fluency. The techniques that we used in the implementation were: predicting, asking and answering questions, connecting the listening to students’ prior knowledge, analyzing, discriminating the authentic materials to the full and applying what has been listened to in order to make decisions about talking and negotiating.

Meaningful Listening Tasks

Melanlioglu (2013) shows that “authentic learning tasks enhance experiences by enabling learners to encounter problematic situations which prepare them for real life listening situations that increase their levels of listening comprehension” (p. 1185). Day and Bamford (1999) explain that listening tasks enrich the EFL learning process. S. Brown (2006) states that meaningful listening tasks encourage students to achieve fluent abilities in the aural and communicative parts of the target language through active involvement. Listening practices include paying attention to what others are saying, avoiding distraction, listening attentively to what is being said, showing respect to the speakers, waiting for communication time, and participating in the conversation. Types of authentic meaningful tasks involve dialogues, debates, oral production, discussion, oral reports, among others.

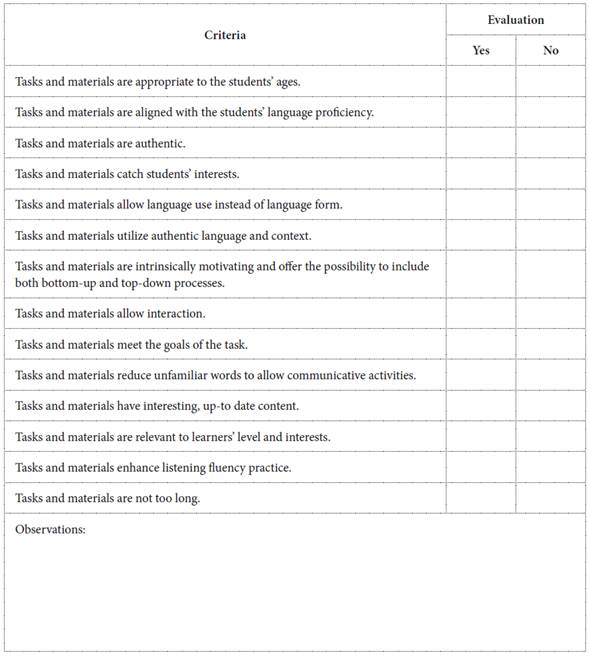

Referring to the criteria to select assignments, Vandergrift and Goh (2012) explain that they should include age, language proficiency, and genre of the authentic materials, the context, and learner’s interests. H. D. Brown (2001) adds some characteristics to select the material: the material utilizes authentic language and context, the materials is intrinsically motivating, the material offers the possibility to include both bottom-up and top-down processes, the material is interactive and allows interaction. The author proposes four steps to select materials and tasks. First, the task and the material have to meet the goals of the assignment. Second, the task and the material have to specify the structures and vocabulary items. Next, they should reduce unfamiliar words to allow communicative activities, and finally, they should be interesting, up-to-date and relevant to learners’ level and interests. In order to select the listening tasks, we designed a rubric in which some of the criteria explained above were taken into account, as well as some other criteria (see Appendix A).

Method

This study was conducted following the methodology of action research. According to Elliot (1991) this method is a type of research that consists of: planning, acting, observing, and reflecting. The cycle starts with creating a plan to observe and record classroom activities (planning). After the plan, an action is implemented to seek a solution to the difficulty that is presented in the class (acting); while this is happening, information is collected (observing) and analyzed. The final stage is to revise how effective the application of the action helps students to overcome the difficulties presented (reflecting). In this study, planning helped us find that students presented some difficulties in listening skills. In order to find a solution to those difficulties, ten meaningful oral tasks were implemented. While we were implementing these tasks, we observed and interviewed to collect information and to reflect on how the students responded to the use of meaningful tasks.

Context and Participants

The participants of this study were ten EFL learners. Six of them were male and four female. The age range was from 17 to 20 years old. They were all in the third semester, in which they had to take a pre-intermediate English course that was part of their education process in the EFL program. These students faced different conditions and situations that affected them in their successful development of listening. First, the geographical context where the university is located impeded learners having contact with native English speakers. Second, most students expressed that they did not practice listening at home and they also stated that the majority of English language teachers have taught them using listening activities in the class just to test them. Some of the activities they used to do before the implementation of meaningful listening tasks were filling the gaps, finding the missing words of a text, recognizing the pronunciation of words, or understanding the intended message of a word.

Data Sources and Analysis

Two data collecting instruments were used in this study: observation field notes and semi-structured interviews. The observations helped to gather information on how the students responded to the implementation of the meaningful oral tasks and the performance shown by them. In this regard, general information about how the students reacted to the use of meaningful tasks, the skills they developed and their reactions to their classmates’ questions and answers were written in the field notes. Specific information such as the role of the topics, materials, activities used to enhance listening fluency, and specific abilities students developed in the application were also collected. The semi-structured interviews served to know the perception of learners about the implementation and to confirm the interpretation of the field notes of the observations.

A constant comparison approach (CCA) was used to examine the data collected systematically. With respect to such method, Fram (2013) declares that the purpose of CCA is to maintain the opinions and perceptions of the participants by making constant comparisons. Following the same matter, Creswell (as cited in Córdoba Zúñiga, 2016), considered that “the constant comparison strategy is a series of procedures that help researchers to analyze and think about social realities” (p. 16). In our study, this process started with the description of the information. Then, we organized, explored, coded, and segmented the data related to the students’ response to the implementation of meaningful oral tasks and how these tasks helped enhance listening fluency. After that process, the first codes appeared: (a) task-based teaching as a way to promote meaningful oral tasks, (b) listening tasks, (c) promoting meaningful oral tasks, and (d) listening fluency. Next, we carefully read the transcribed information line by line and divided it into meaningful segments to corroborate and validate the data through triangulating and making comparisons to finally get the results.

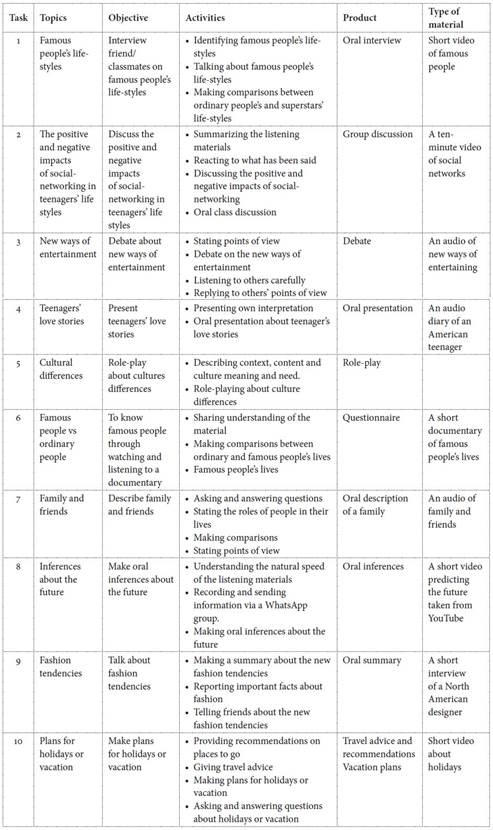

Pedagogical Intervention

For the pedagogical intervention, ten meaningful listening oral tasks were designed and implemented (see Appendix B). These assignments were based on students’ ages, interests, their English level and avoiding any controversial issue. The topics, context, and the materials (authentic videos, oral documentaries, interviews and recordings, and class oral conversations) varied to provide effective listening practice. These assignments lasted 40 hours and were developed within ten weeks during the second semester of 2016. Each task took four hours to be developed (half an hour for pre-listening activities, three for the development of the task, and another half an hour for post-listening tasks).

Pre-Listening Phase

In this phase, the participants were informed about the main purpose of the study and some recommendations were also provided for the students. The suggestions advised students to listen to the materials at home at least twice; to complete every task; to follow the recommendations and criteria of each task and to take notes, ask, and answer questions; and, ultimately, to be ready to perform the assignments successfully. Additionally, we asked the participants to present their product of each task in the while-listening phase and to do the follow-up activities if needed.

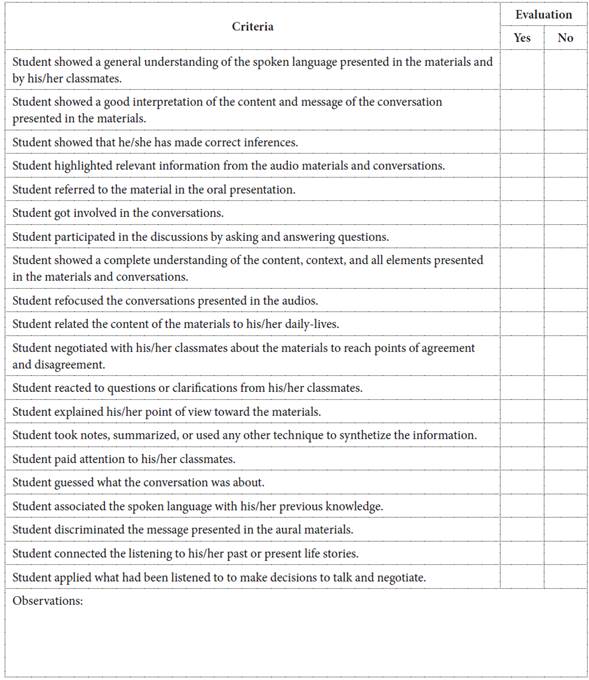

While-Listening Phase

During the development of this phase, the students followed some steps: (a) they listened to the audio resources in the class; when the listening materials were played, they took notes and activated their prior knowledge about the topic (see Appendix B); (b) during the while listening stage, the learners presented the product of the meaningful oral task; while they were doing that, their classmates paid close attention, took notes, asked and answered questions, exchanged points of view, and made comparisons between their interpretations of the content, context, and messages with the points of view of their classmates. Meanwhile, we listened to them attentively, took notes and evaluated learners’ performances by using a flexible listening rubric created by us (see Appendix C).

Post-Listening Phase

In this final phase, we first congratulated students for their performance and motivated them to continue doing the implementation. We also showed and gave the rubric and notes to the students with some recommendations on how to manage the time given for the activity, some guidance on choosing the appropriate vocabulary, how to use more supporting details, to connect oral messages to their context, and to express their ideas clearly. These recommendations were given mainly at the beginning of the study. After each assignment, new questions were asked as an illustration and to recycle the topics that had been previously studied.

Findings and Discussion

In this section, we present the findings and discussion of the information collected during the pedagogical intervention.

Task-Based Language Teaching as a Way to Promote Meaningful Oral Tasks

The analysis of data suggests that TBLT may be an effective methodology to promote listening fluency in EFL learners. The participants developed significant oral tasks in which they were engaged in step-by-step assignments that offered opportunities to analyze, synthesize, evaluate, and apply their knowledge to participate in listening and speaking tasks at the same time. Participants state that:

TBLT created a new atmosphere in the classroom to practice listening and speaking, I first listened to the materials at home, to make connections with the speaker and the message. Then, when the audio was played in the class, I could understand, talk with my classmate, and report my thoughts about the materials. (Interview 2, Participant 1)

The participants acknowledged the use of TBLT because this approach offered a framework to practice listening to a process that let them construct meaning as well as to participate in oral communication activities that served to exchange thoughts in relation to the recordings. As can be seen, TBLT offered a possibility to create a different classroom dynamic where the students went through some stages such as pre-, while-, and post-listening that facilitated the development of assignments and encouraged their participation in authentic conversations that increased listening and speaking practice.

Bearing in mind that the primary concerns of the intermediate EFL learners were the lack of fluency for listening practice, meaningless methodology to teach this ability, and limited students’ background in this skill, the use of TBLT provided significant opportunities to overcome those limitations. These tasks facilitated exploration and listening production and created opportunities to be fluent in the listening skill. They also offered a meaningful plan of action that included pre, while, and post stages in which the students became independent, reflective team-workers and creative and effective participators of their learning process. These findings are linked to Córdoba Zúñiga (2016), Ellis (2003), and Willis and Willis (2001), who considered that TBLT offered the possibility to enhance practice, class productivity, and learning.

Listening Skill and Listening Tasks

In this study, listening tasks refers to all assignments developed by students to understand, analyze, connect, and apply the content of spoken language to systematically increase their listening fluency. In this regard, data on how the students responded and reacted to the pedagogical intervention indicate that the assignments required pre, while, and post listening phases. The pre-listening task was necessary to activate students’ knowledge, encourage them to ask for any clarification, discuss the criteria of the task, and to provide the instructions to be followed. Additionally, it served as a way to embark learners into the tasks and to increase their possibilities to complete the assignments.

With respect to the pre-listening stage, Participant 3 expresses that “pre-listening tasks helped [him] to have a general understanding of what to be done during the tasks” (Interview). Equally, we observed that

Pre-listening exercises were important for the students to clarify what, how, and when to do the tasks. Also, they were important to introduce them to the world of the tasks by asking them to make inferences about the message and information of audio materials and conversations. (Observation field note)

The previous evidence suggests that the pre-listening task was very important to recognize, identify, and facilitate the development of the tasks. This stage provided support, clarified what the students were asked to do, and expanded information on how and when they were called to each task. In other words, this phase was the first journey into meaningful oral task travel, and as such, all the necessary information needed to do the tasks had to be provided.

The most important feature of this phase was that students presented the product of the meaningful oral task with which they showed they had fully understood the content of the aural materials and had restated, reorganized, connected, and applied it to their lives to finally create their own interpretation of the information. At this stage, the students showed points of agreement and disagreement and when all had finished their presentations, more discussions and negotiation started to expand the comprehension of the materials.

Participant 9 says that “this stage increased her understanding of the material because she was involved in permanent discussions that illustrated her to perform her task” (Interview). We found that

Students showed positive reactions when they participated in discussions and were performing the activities. The learners made decisions, negotiated, reached agreements, and actively participated in the conversation in which the aural material was described totally. (Observation field note)

A possible explanation for the aforementioned data would be the fact that active oral and listening practice such as analyzing, organizing, making predictions, and connecting the oral messages to students’ lives and speech provided students with more possibilities to evaluate the speaker’s point of view and intentions. Discussions, exchanging points of view and the presentations evidenced that listening fluency may be achieved in a high percentage in this phase. Another possible explanation is that constant listening tasks were helpful for learners to master the ability to interpret and connect speakers’ points of view with students’ real lives. Based on these interpretations, it could be said that while-listening was a major stage of the intervention. At this step, students expanded their ability to discover, explain, discuss, and to report their points of view orally.

Furthermore, we should insist that it is important that, while students make their presentations, their partners should be paying close attention and taking notes to evaluate each student’s performance through a flexible listening rubric (see Appendix C). This rubric was a form designed by us to evaluate how the students developed the assignments and how their development demonstrated progress in listening fluency or not. This had to be done with a formative purpose and not to punish students if they presented difficulties understanding the global message of the speech. This instrument should be given to the learners before and after their presentation, so that they can reflect upon the areas they might study and need to overcome after they have made their presentations.

The final phase-the post-listening stage-served to recycle and to underline specific or general areas to work on identified in the while-listening stage. If there are any suggestions, they should be for the task itself such as time management, engagement or level of complexity or for the performance of the students during the development of the previous stage. Participant 1 comments that “this phase helped [him] to realize that [he] pronounced some words wrongly” (Interview). From our perspective, this final stage offered opportunities to reflect on students’ performances and to explore new alternatives to strengthen listening fluency.

Promoting Meaningful Oral Tasks

As pointed out in the introduction of this paper, promoting meaningful oral tasks was the central pedagogical intervention proposed to enhance listening fluency in the participants. In this order of ideas, the information suggests that meaningful oral tasks worked as a possibility to broaden learners’ opportunities to master this skill by providing authentic oral tasks in which they were asked to pay attention to the spoken language, to think, react, ask and respond to questions, and participate in authentic oral conversations. Tasks demanded rehearsal, interaction, oral discussions, presentations, debates and interviews, decision-making, and creativity to connect the oral messages of the materials to students’ real lives.

Participant 8 mentions that “meaningful oral tasks were not only related to the message of the conversation, but also gave the opportunity to interact with their classmates” (Interview). Participant 7 explains that “meaningful tasks offered a real possibility to improve listening by doing assignments that were related to [her] life, and as a consequence, listening was improved” (Interview).

We consider that there were several possible explanations for the previous results. First, meaningful oral tasks promoted authentic exposure, practice, and a suitable atmosphere in which the participants effectively refocused the spoken language according to their needs, intentions, and communicative goals of each assignment. Second, the students developed the skill to connect their knowledge, to uncover the messages that spoken material and conversation conveyed. In other words, they learnt to predict, analyze, and make inferences to interpret verbal and nonverbal information presented in the oral material and conversations. Another main point was that these assignments were a dynamic process that included the possibility to share viewpoints, discuss, and ask and answer open-ended questions which enhanced oral listening interaction. Equally important, tasks included updated topics that matched students’ ages, interests, and English level and this may help to increase the possibilities to be engaged in the tasks development.

Additionally, the activities introduced learners to a cycle that encouraged them to practice listening fluency and oral interaction simultaneously. They had to concentrate to avoid misunderstanding and misinterpretation. So, the students’ abilities to recognize general content of spoken messages, to remember main ideas of conversation, to analyze the speaker’s intention, and to relate the oral messages to their lives increased significantly. Participant 6 reveals that “after the intervention of meaningful oral tasks I can be more engaged and focused in the tasks” (Interview).

This perception is due to the lack of listening fluency exercises the students had before this study. As was studied in the introduction, one of the difficulties that students had was the types of meaningless listening exercises. Yet, implementing these assignments encouraged them to recognize that listening demanded comprehension, attention, thinking, acting, applying, creating, and responding to the tasks committed to them meaningfully. The students went beyond recognizing simple words or understanding the meaning of a word to relate the aural message to their daily conversations, experiences, and lives; by doing that, learners became willing to seek opportunities to practice this skill at home.

Listening Fluency

As we pointed out in the introduction, listening fluency was the main weakness that the participants had before the study was conducted. Then, a pedagogical intervention was proposed as a way to promote this skill. The information collected during the implementations indicate that this methodology provided exciting opportunities to foster listening fluency through the development of meaningful dynamic oral assignments that included pre, while, and post intensive-extensive listening practices which allowed learners to understand, interpret oral messages, and provide suitable responses to do the tasks committed to them.

We observed that

Doing different listening tasks helped students to overcome the difficulties that they had before the study was conducted. They shared, talked, and demonstrated that they understood the topic and the content of the conversations. (Observation field note)

During the assignments, the participants demonstrated a significant advance to comprehend, analyze, interpret, and decode oral messages. The tasks provided students with helpful experience that had a positive impact on their pronunciation, intonation, rhythm, music, and sounds of English. The experience they gained from developing their exercises made them feel comfortable, confident, and self-sufficient English learners.

Additionally, meaningful oral tasks seemed to be a good way to make connections between the speech, what they knew and how they wanted to express themselves. Students reacted, responded, and asked questions that increased their possibilities to restate, understand, and apply information from the material to express their ideas. This was achieved because listening tasks were seen as an integrated process in which the student did pre, while, and post listening activities which encouraged them to develop understanding. This process helped them to clarify and verify the content of the audio-materials and daily-life conversations by developing engaging activities where listening was examined beyond instructional or literal interpretation. Participant 1 states that “spoken activities helped to improve listening because they helped to construct meaning and expanded listening comprehension” (Interview). This participant had this perception about meaningful oral tasks because these assignments gave him the opportunity to be involved in active listening fluency activities, in which students had to apply all that they had gathered from the materials or classroom conversation to participate in the discussion or to report their interpretations to the group. Likewise, they practiced the meaningful listening tasks that required engagement, oral classroom interactions, decision-making, and creativity.

Another reason was that meaningful oral tasks emphasized offering opportunities to practice listening fluency from a variety of activities and tasks which took into account students’ ages, culture, level, and interests. This ensured participation, the development of the task by students, and provided many possibilities to review their knowledge which may be a successful way to promote listening fluency.

Participant 2 suggests that the tasks were close to her real-world life and revolved around her interests and what she could do with the language (Interview). In the same way, we find that “students showed interest in the tasks because they did not see them as something beyond their lives” (Observation field note).

From our perspective, the development of meaningful oral tasks was an effective way to enhance listening fluency for three main reasons: First, tasks were directly connected to students’ real life; they discussed, described, and made oral inferences to understand what the speakers tried to say. Second, the tasks offered learners the opportunity to activate prior knowledge and to be familiar with the topics. Additionally, tasks helped students to connect, recognize, interpret, and understand and to be involved in meaningful conversations such as negotiating, exchanging points of view, discussing, or reaching agreements about the message of the materials.

Conclusions and Suggestions

As pointed out in the introduction to this paper, most of the pre-intermediate EFL learners presented serious problems in listening tasks. They misunderstood and misinterpreted oral messages and were unable to recognize the general content and encountered difficulties to refer to the aural materials or conversations orally. Based on that, we decided to conduct an action research that involved 10 meaningful oral tasks, where the students practiced listening activities to develop the tasks committed to them. This process included three main stages: pre, while and post listening tasks. In each phase, the students practiced, negotiated, examined, and performed a variety of oral and listening assignments that were planned following the principles of TBLT and included diverse topics (see Appendix B). The exercises were designed and applied considering students’ ages, culture, religion, and English level. It can be concluded that the implementation of meaningful oral tasks promoted listening fluency in ten pre-intermediate EFL learners in the ELT program at the Universidad de la Amazonia in Florencia (Colombia) for various reasons.

First, listening tasks were meaningful learning activities that encouraged learners to practice this skill effectively through a systematic action plan that followed pre-, while-, and post-stages. The students developed real world assignments, in which they analyzed, related, applied, and constructed meaning from the materials to actively participate in oral discussions. Apart from promoting listening fluency, this study showed how the EFL teachers may involve students in interactive listening assignments that offer class interaction to help students to confront listening comprehension difficulties.

Meaningful tasks encouraged learners to seek and provide creative and innovative responses, solutions, or evidence of their learning process rather than merely recall or repeat the information that the speaker provides. These activities engaged students in challenging problem-solving and decision-making oriented classes, where the students needed more than one step to complete the task required. In addition, the assignment took into consideration students’ personal background to broaden the possibility for learners to actively participate in the development of the task. We also concluded that listening fluency can be promoted by contextualizing and personalizing listening activities.

Further analysis should be conducted to analyze how meaningful oral tasks enhance other communicative skills such as reading or speaking. It would be good to examine how reading comprehension could be enhanced through oral tasks. It would also be interesting to study if TBLT could be applied to teach meaningful writing practices.