Introduction

The perception that has to do with a heavy emphasis on theory about pedagogy and research implicit in the contents and activities of English language teacher education programs conveys an idealistic or utopian aspect of language education. Said perception leads teacher educators to overlook the realities of their student-teachers and what they do in and out of the programs they attend. In response to that, the study shared via this article had as a purpose to foster, through a pedagogical intervention, some sensitivity towards the social and critical dimensions of language education in contexts that were immediate to its participants. This aim called for an inquiring attitude about some trans-formations concerning views and practices of language education and learning, and the way those transforming views and practices, in turn, shaped a group of student-teachers’ formative research projects. The question that guided the study: How are English as a foreign language (EFL) student-teachers’ formative pedagogical and research experiences portrayed in a transformative and critical outlook for initial teacher education?

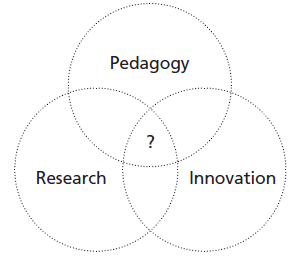

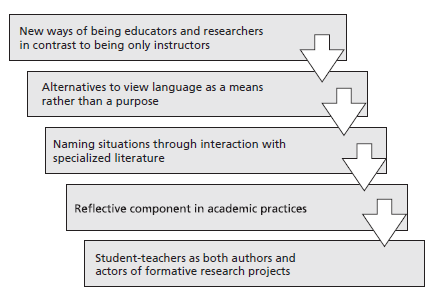

The rationale for the study, within a pedagogical innovation framework, relates to the belief that implementing transformations in the traditional educational practices in teacher education programs becomes essential. Such is the intention of this article: to encourage members of the local and global English language teaching community to not remain as mere viewers of the educational scene, but to take an active part, that is, to give themselves voice and give voice to other teachers through research agendas. The statements and discussions about the intersection of pedagogy, research, and innovation in language teacher education are proposed here under a humanistic, inquiring, and critical approach to language teaching and learning (see Figure 1). Thus, the mere linguistic and instructional dimensions of language education should be overpassed (Quintero, 2011), and one way to achieve that is by inquiring about what lies within such intersection.

Theoretical Considerations

The theoretical considerations of this article propose a discussion of three main topics: the Freirean philosophy of education, teacher knowledge, and trans-formation of pedagogical knowledge.

The Freirean Philosophy

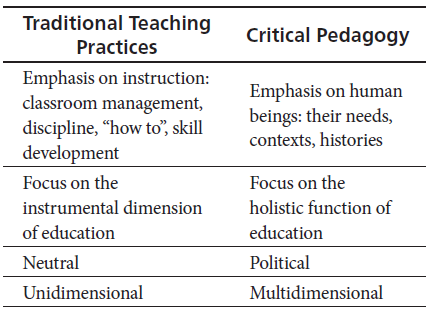

The intersection of pedagogy, research, and innovation in language teacher education can be discussed from a critical perspective, which in this work is provided by the Freirean philosophy, better known as critical pedagogy (McLaren, 2003; Norton & Toohey, 2004; Wink, 2005). Such philosophy, conversely to traditional ways of teaching, sets some principles for educators and learners to make sense of the world where they live (Table 1).

Critical pedagogy is not a method, but it is rather a way of life (McLaren, 2003). If, from a social perspective, focus is placed on the visible and hidden human interactions between a teacher and a learner in an educational institution or beyond it, then critical pedagogy will have to do more than just concerning itself with what and how students learn and what and how teachers teach (Norton & Toohey, 2004). From this perspective, Wink (2005) maintains that critical pedagogy allows educators to look at political, ideological, social, cultural, economic, and historical issues “to name, to reflect critically, and to act” (p. 3).

In the same line of thought, the tenet that subsumes the principles for the practice of language teaching and learning is the understanding of the world as a multidimensional entity which entails a multiplicity of views on school life. Schools are places where language, literacy, and culture meet; schools are contexts within which different practices are carried out by people (Nieto, 2010). In this sense, teaching and learning are both cause and consequence of the social, cultural, political, economic, and historical practices (Guerrero & Quintero, 2004).

The above referred practices take place through an empowering dialogical interaction between teachers and learners mediated by language (McLaren, 2003; Shor & Freire, 1987). Language is viewed as a vehicle that not only reveals dialogical relationships between teachers and learners, but that also constructs them (Pennycook, 2001). This dialogical construction relates to the social dimension of education (Vigotsky, 1989) and implies that teachers learn with and from learners (Shor & Freire, 1987). Teachers also play the role of learners, not merely the role of transmitters of ready-made knowledge; that is, an external packet of information for teachers to impart in an acritical manner (Freire, 1992).

Teacher Knowledge

In line with some tenets of critical pedagogy, in the theoretical considerations for this article, appears the topic of knowledge in general and teacher knowledge in particular. The latter is the focus of attention in this section.

The areas that need to be covered in a research agenda that intends to explore how pre-service and in-service teachers think and work are conceptions of teaching, dimensions of knowledge, and teachers’ lives and careers (Golombek, 1994; K. Richards, 1994). The dimensions of knowledge comprise an area that relates to this paper most directly. A view of knowledge as an external body of information for people is likely to lead to a focus on imparting that information, a focus on content; conversely, if the knower is not separated from the known, the focus is more likely to be on engagement and exploration. Such area is considered to influence a characterization of pedagogy and pedagogical knowledge. This relates to one of the main goals of research, namely, to transform already existing knowledge or to produce new knowledge. This conception applies as much to the investigation of teacher knowledge as to knowledge itself. Shulman (1987) offers a formula to conduct research in distinct areas of teacher knowledge (Table 2).

The types of teacher knowledge, which are objects of discussion in this work, are: (a) general pedagogical knowledge and (b) pedagogical content knowledge. The former can be understood as the general set of methodologies and strategies for teachers to deliver their teaching. The latter can be related to the capacities and understanding of how to teach the subject matter in a variety of ways to allow teachers to attain their objectives. These dimensions of knowledge then are the ones that are intended to be linked to the idea of trans-formation informed by critical pedagogy for developing an epistemology of language pedagogy.

Trans-Formation of Pedagogical Knowledge

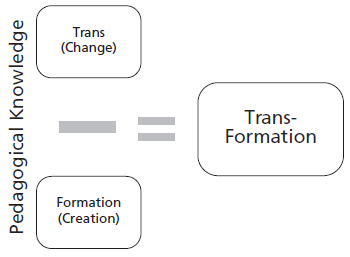

In relation to what has been mentioned, an interest in the conceptualization on trans (change) formation (creation) of language pedagogical knowledge arises. Figure 2 gives one a look at how the terms innovation and change become relevant here. Brief definitions of the two terms are proposed by Quintero (2011): “Innovation is related to the individual and collective intentions to implement new alternatives in educational practices. As for change, it relates to the perspectives from which educators see their own implementation and duration of their innovations” (p. 1). The account for this situation by the protagonists of educational practices constitutes what can be called trans-formation (Piñeros & Quintero, 2006).

Trans-formation should be a teacher-initiated activity based on teachers’ knowledge of and identification with their students, awareness of their strengths, and disclosure of their privileges and biases in the schools where they teach (Piñeros & Quintero, 2006). In addition, searching for educational alternatives and abandoning the “comfort zone”, recipes and prescriptions to teach are features of teachers that can be called transformative professionals of language education (Nieto, 2003).

Regarding pedagogical knowledge, reference needs to be made to a humanistic dimension of knowledge. In that sense, Brown and Duguid (as cited in Fullan, 2001a) make a distinction between the notions of information associated with machines, and knowledge associated with people. Fullan proposes the idea that knowledge is not information, or that the accumulation of information can be converted into knowledge. Such conversion calls for the intervention of the individual and collective dimensions of people, that is, the emotions, aspirations, hopes, and intentions of individuals as well as social groups.

Knowledge is also discussed by Piñeros and Quintero (2006) as a compound of theory and practice that is activated and created through contextualization and sharing. The theoretical part of such compound relates to the basic concepts of teacher education, and the practical part refers to the learning and teaching experiences in school settings. Such compound, in turn, has both an individual and collective dimension. The former entails attitude formation towards the world as the cause and consequence of knowledge construction; the latter denotes the social factor that takes place through sharing and debating.

In regard to the individual and collective dimensions above, Fullan (2001b) maintains that personal and group experiences of knowledge construction lead to change. Change can result in a “sense of mastery, accomplishment, and professional growth” (p. 32). The individual and collective elements of the roles played by actors in exchanging knowledge are key factors in transforming tacit knowledge into shared knowledge.

The Pedagogical Intervention

The pedagogical intervention implemented in this study took place at the English language teacher education undergraduate program of Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Colombia, (Universidad Distrital hereafter). In a vertical view of the curriculum of that program, three cycles are seen: one of foundation (first four semesters), one of deepening (from fifth to eighth semester), and one of innovation (ninth and tenth semesters). On the other hand, the curriculum, seen horizontally, has some training fields where several subjects are aligned. The fields of formation of the program are disciplinary, pedagogical, investigative, and ethical and political. In particular, the intervention of this study was initially implemented in the academic spaces or subjects of Interdisciplinary Seminar VIII and Pedagogical Project I in 2005. The structure of the intervention was replicated with small refinements in new cohorts in further years. The Interdisciplinary Seminar belonged to the research field and the subject of Pedagogical Project I was part of the pedagogical field. Both subjects belonged to the deepening cycle of the curriculum of the program, in its eighth semester.

The Interdisciplinary Seminar VIII was designed to discuss alternatives and serve as the basis for the articulation of research proposals of future English language teachers. The academic space of Pedagogical Project I, in close connection with the Interdisciplinary Seminar VIII, sought to help future English language teachers to consciously look at the implications of being a novice teacher researcher. The future English language teachers were involved in the elaboration of a research, pedagogical, and innovative proposal.

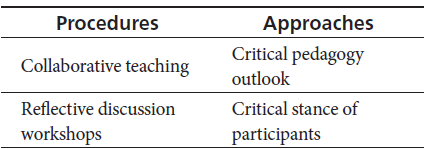

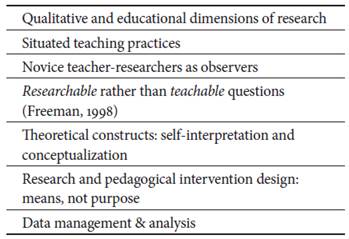

Both subjects included, as shared features, modeling and exemplifying new approaches and procedures, such as the ones contained in Table 3 and described after it. This constituted an innovation in the English language teacher education program where this study took place. As part of the intersection of pedagogy, research, and innovation, there was a collective understanding that it was teacher educators’ responsibility to create spaces of reflection and discussion about what the sociocultural reality of schools is, and how all the educational community made different interpretations of such reality within a pedagogical innovation framework. Such common understanding was, in turn, linked to the need of some transformations in the traditional educational practices in the EFL teacher education undergraduate program of Universidad Distrital (Table 3).

Collaborative teaching allowed professors to identify needs, share experiences and knowledge, plan content and courses of actions in the class, and establish a solid methodology that ensured reflection, discussion, and action (Pineda, 2002). Collaborative teaching, in this study, was established between two professors of the Interdisciplinary Seminar and two professors of the subject of Pedagogical Project I in the same semester, but two groups, one in the morning shift and another one in the afternoon shift.

The reflective discussion workshops, from an autonomous learning perspective, were given a turn from the traditional lectures of the teachers to become spaces for discussion about the teaching and learning of EFL; the view of language, literacy, and learning; and the student-teachers’ research process: before, during, and after. The critical pedagogy outlook had as a main characteristic the fact that the student-teachers’ reflections and research experiences were grounded on the tenets of critical pedagogy. The selection of the readings or the contents for the courses had in common a socio-critical perspective of education and, as a complement, were based on specialized literature on qualitative research and innovative pedagogical interventions in the language classroom. The critical stance of the participants included a view of language research as a means, not an end, for the exploration of social, cultural, and political issues that were part of the realities of their language educational contexts. That stance also facilitated an environment for reflection, discussion, and feedback on the student-teachers’ research proposals.

The procedures and approaches above were also intended to bring about an appeal for the theme of knowledge trans-formation in the participating student-teachers. Figure 3 summarizes such appeal.

The student-teachers started to self-position themselves as both authors and actors of research projects since they started to observe the need to find alternatives to view language as a means rather than a purpose. Furthermore, they discovered new ways of being educators in contrast to being only language instructors (i.e., the dialectical dimension of pedagogy mentioned above). They also started to name situations, which they did not know beforehand. This happened because of the interaction with the literature that shaped their discussions. This also led them to analyze the reflective component in their academic daily practices in the EFL teacher education program and subsequently analyze some actions that in turn became research projects, at a formative level, for their monographs.

The Research Experience

The systematic and formal experience that substantiated some EFL student-teachers’ development of formative research projects resulted from the intervention described above. With an implicit intention to challenge the traditional conception of research as something that is done on teaching, the study was proposed following the idea of research as something that can also be done by teachers to inquire into student-teachers’ alternatives to establish connections between the theoretical components of the subjects in a plan of studies and their educational experiences observing sensitivity towards the social and critical dimensions of language education in their contexts.

The Research Problem

The problem addressed through the study was conceived after an observation carried out in the EFL teacher education program at Universidad Distrital, which served the purpose of documenting both language and teaching as the objective of instructional techniques that were geared towards language skill development and the confirmation of the effectiveness of those techniques. Reflection had not occurred so frequently. Little or no inquiry into social and cultural phenomena had been practiced except for some isolated efforts. This situation can be associated with the replication of positivistic approaches (Kuhn, 1970) to education, which usually leads to overlooking the realities of the students.

A positivistic emphasis on language teaching and learning resembles the model of “training” that Woodward (1991) characterizes with an emphasis on the instructional practices, that is, the “how to” of teaching (Giroux, 1988); for instance, discipline management, group management, motivation techniques, development of language skills, time management, adequate and proficient use of English, and other products of the same nature. One reason for that model to be problematic is given by Fandiño (2013). He reviews literature about how Colombian EFL teacher education programs are addressing teacher knowledge and draws the conclusion that learning the basic skills required for teaching, mastering a subject matter, and using pedagogical skills is never enough to build a knowledge base. For Fandiño, it is also necessary to keep a balance between theory and practice by reflecting on what Colombian language teachers feel, think, and do to inform their learning and teaching practices.

Another model described by Woodward (1991), called “educational,” has a more holistic and focused approach to teacher reflection. It focuses on forming an efficient instructor; however, the same as the “training” model, it ignores critical factors of teaching, such as getting to know students, what needs they have, and in what context education is developed. In relation to that, Cárdenas (2009) states that though socially-oriented paradigms are starting to be observed, transmissionist and skill-based models continue to be a tendency in many Colombian language teacher education programs. She considers that a sort of eclecticism of behaviorist, humanist, constructivist, and reflective perspectives are being taken for granted with unclear conceptualizations and unawareness about the need to see teacher education as a multidimensional practice.

J. C. Richards and Lockhart’s (1994) “reflective model” values teachers’ reflective practice as the origin of trans-formations, conversely to training models in which others are who decide what should be done and known (González, Montoya, & Sierra, 2002). Nevertheless, that “reflective model” also emphasizes the instructional, in being what is called “a good teacher”, mainly from the technical point of view. Linked to that, Álvarez (2009) states that the technical aspects of language teaching may very well represent some value, but the humanistic dimension of education needs to be paid attention to as well by teachers through research agendas.

With the research problem in mind, a question that guided the development of the study emerged: How are EFL student-teachers’ formative pedagogical and research experiences portrayed in a transformative and critical outlook for initial teacher education? The objectives of the project were: To characterize student-teachers’ formative pedagogical and research experiences, and to analyze the innovations that student-teachers show, as such, from their own perspective.

Participants

The EFL teacher education program of Universidad Distrital receives students, men and women, who are mainly young adults (students of 18 to 21 years of age). The students mainly come from low-income families who live in southern Bogotá, Colombia. The five participants in this study were taken from a group of fourteen future English teachers who participated in the academic courses Interdisciplinary Seminar and Pedagogical Project, which were described in the pedagogical intervention above. The participants authorized the use of written information in their diaries and an audio recording of their oral interventions in interviews by signing a consent note. The participants were selected from those who had completed a number of eight reflections about the readings discussed in class and were completing their pedagogical and research proposals. The names of the five participants have been replaced by the initials of the words student and teacher in order to maintain their confidentiality, as follows: ST1, ST2, ST3, ST4, and ST5.

Method

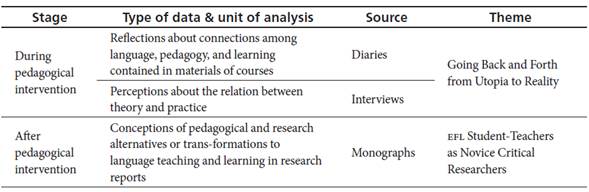

The study was a descriptive and interpretive qualitative one (Creswell, 2012). The overall purpose of this research approach is to make sense of naturalistic data, and the reasons for choosing them in this study are twofold: one being ontological and another one being epistemological. The former is related to the view that social reality is not static, singular, or objective, but is rather shaped by human experiences and social contexts. The latter has to do with the fact that social reality calls for subjective characterizations and interpretations of its various participants. A process of data management and analysis was developed within a reflective and critical atmosphere fostered through the pedagogical intervention. Table 4 summarizes the way data were guaranteed in this study.

Data collection was done in two points in time: (a) reflections and perceptions through diaries and interviews during the intervention, and (b) conceptions through monographs, after the intervention took place. The participants wrote reflective diary entries as one activity following discussions about reading materials on the subjects of Interdisciplinary Seminar and Pedagogical Project. The interviews were conducted soon after the courses ended (see Appendix). The monographs-degree works that reported on pedagogical and small-scale research studies-listed in this article were selected based on two criteria: (1) relevance to the concept of innovation and coherence with the idea of practical realization of alternative views about language, pedagogy, and (2) learning previously identified in diaries and interviews.

Findings

After analyzing data, the main emerging themes were “Going Back and Forth from Utopia to Reality” and “EFL Student-Teachers as Novice Critical Researchers”.

Going Back and Forth from Utopia to Reality

The participation of the EFL student-teachers became a stroll between utopia and reality: In pedagogy, they undertook negotiations with themselves, with their academic formation and with their pupils; in research, they engaged in applications of the qualitative paradigm to projects oriented to knowing their students and projects that involved parents. Going back and forth between the dialogical and dialectical dimensions of pedagogy (Kincheloe, 2004) during the teaching practicum was reflected in the internal and external negotiations of the student-teachers. The former were understood as the questioning of their own beliefs as compared with theory and practice; the latter were related to decision-making and innovations within the classroom, negotiations between the knowledge derived from experiences and the knowledge received during the academic formation. The following excerpts illustrate this:

Pedagogy. This is the first thing we should be clear about. Most of the time I feel that pedagogy only refers to reflection on teaching. However, it is fully connected with learning and with learners, so that whenever we say pedagogy, we always look at the relationship between teaching and learning and all that this implies in terms of people, contexts, and practices. (ST1, Diary)

It was first the two components, the practical and the theoretical part . . . the theoretical part because it greatly influenced us and made us interpret the critical pedagogy as something humanistic and social, not only as a concept, it was negotiation and dialogue as something that occurred within the classroom. Then when we were talking about negotiation in academic and social settings, we saw that the community and the school should be interconnected. (ST3, Interview)

In these excerpts, an attempt is made to relate an idea about pedagogical knowledge to real and contextualized situations. In this sense, pedagogy becomes experiential and socially situated, and knowledge turns into something real and tangible (Shor & Freire, 1987).

Being in contact with literature on critical pedagogy led the student teachers to identify controversial aspects of educational practices inside and outside the language classroom. They reported on a dynamic, in contrast to a static, feature of education by referring to pedagogical practices as tasks that involved naming educational phenomena, reflecting, and acting on them critically (Wink, 2005). Regarding this, ST2 reflected:

I know that language and learning are not static and that we can learn from anyone, but I am not aware of who, however it is. (Diary)

Focusing on the dialectical dimension of critical pedagogy, the student-teachers faced challenges and dilemmas that led them to search for a bridge between theory and practice of language pedagogy as a situated activity. In other words, language pedagogy became a set of alternatives to establish connections between language and their real-life issues. ST1 and ST2 manifested that

There are many possibilities, and in any case, you will always have certain limitations where you work because you have to comply with things, things that the institution demands, be it a school, an institute, a university; however, I think that one learns to establish a balance between what one has to do, what one has to do in terms of an instructional part, and what one can actually accomplish with the students there. (ST1, Interview)

It was a rejection first, but then the opportunity to negotiate was given. All kinds of negotiation, with myself, with the theory, with my students, etc. I did negotiation through dialogue. It became a lifestyle, I began to be critical in all aspects, it was no longer only in pedagogy, it was as I acted, as I thought that everything transcended as a way of life. (ST2, Interview)

It can be noted that the emergence of tensions was mediated through negotiation. Negotiation became a change in the lifestyle of the participants. The dialogical dimension relates to the attitude of the teachers towards knowing the students, establishing a dialogue through strategies and instruments that facilitate a direct interaction between the people involved in educational events. This is what in critical pedagogy is called “dialogue as a human phenomenon” (Freire, 2002, p. 87). This constitutes an innovation for the participants of this study since their conceptions about language undergo a transition from seeing it as a system of linguistic forms and abilities to see it as revealing, constructing, and transforming relationships between people (Pennycook, 1994).

At first it was difficult because I did not understand well [what] critical pedagogy meant through the readings I was doing. Later, I realized that the role of a teacher described in the readings of critical pedagogy had a realization when I did not stand in front of my students as if I wanted to fill them with the little or much I knew and thought could serve them. I also realized that being an instructor was totally different from being an educator. It was a very different thing. (ST4, Interview)

In this extract ST4 showed a dialectical dimension between the roles of instructor and educator. The dialectical view of pedagogy refers to the fact that what is taught does not necessarily correspond to what the students need or to what the students themselves end up learning according to their own needs and interests. ST5 declared this about it:

I work in a school where students are required to have a high grammatical knowledge so that they develop speaking. Knowing that I have to teach the structures that are a requirement of the school is a shock since I do not want to do such thing, but I know I must do it. There is a fight that one has inside. I have to cover the topics that have to be covered but at the same time I try to take my students’ needs and wants into account. (Interview)

Implicitly, ST5 gave hints about two things: (a) the fact that there was a gap between the school (official) curriculum and a real-life curriculum and (b) language went from being a purpose to being a medium for exploring the human dimension of people. It implies that ST5 also showed a struggle between what she had to do and what she wanted to do as a language teacher. This represents how the dialectical dimension critical pedagogy took place.

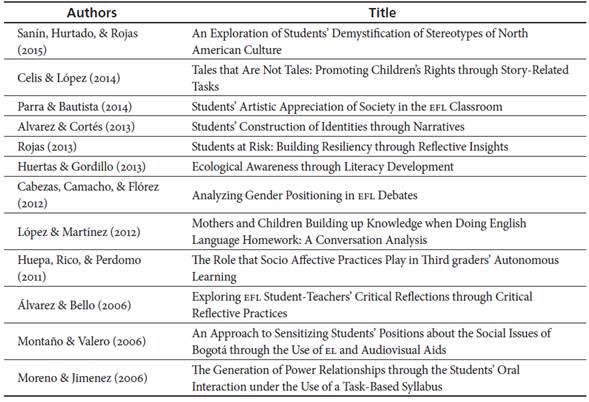

EFL Student-Teachers as Novice Critical Researchers

A description of some features of formative pedagogical and research projects contained in degree works (i.e., monographs) completed by the student-teachers serve the purpose to illustrate the shape that innovation took in the EFL teacher education program of Universidad Distrital, and that led them to position themselves as critical authors and actors of their projects (Table 5).

The degree works that were considered here can be characterized as instances of qualitative research studies that focused on going beyond the implementation and evaluation of the effectiveness of EFL instructional strategies. Overall, the student-teachers’ proposals emerged from their personal interest in exploring and understanding the causes and consequences of pedagogical practices that they had either experienced or observed in their classrooms during their teaching practicum.

In order to define the issues to work on, the novice teacher researchers went through a process of observation and reflection inside and outside their classrooms. Such observation and reflective practice led them to think about aspects that transcended instructional matters and were related to social issues of their educational communities, the needs of their learners, and their own queries and interests as educators. From that point, they started to document, both practically and theoretically, the existence of genuine research problems, which in turn led the student-teachers to pose some research questions that could guide them along the process and that condensed their concerns. In general, they addressed researchable rather than teachable questions, which means that they were open-ended and redefined in the face of the data or with the insights resulting from retrospection (Freeman, 1998).

The problem and questions demanded from the student-teachers some conceptualization of related theoretical constructs. For this, they engaged in a process of reviewing specialized literature, both theory-based and research-based. It is possible to say that the literature review of the projects revealed the relationship that the authors established between the theoretical information and their own understanding of the phenomena under study.

Having the foundations of their studies, the student-teachers went through the research design of their projects. At this stage, they needed to decide on the type of data and units of analysis required for their research questions and the methods to gather such data. One aspect to highlight here is the fact that the research projects considered the voices of participants, such as introspections, testimonies, declarative statements, and so on, as data. Some data collection methods included observations, interviews, journals, and artifacts, among others. The student-teachers considered different strategies for validity and reliability of the data management and analysis.

In relation to the pedagogical component of the novice teacher researchers’ projects, it can be said that most of them had a pedagogical intervention design. It was closely related to the role of participant observers in their teaching settings. They acted as assistant English teachers at some public schools with learners from different grades, but they were allowed to design a syllabus and lessons that considered a set of instructional objectives and a variety of activities that helped to create an environment that served a dual purpose: language development and data collection.

Once the student-teachers had collected data, they moved to the next stage which was the analysis of such data. In doing so, the student-teachers identified and defined some categories intended to answer their research questions. Such categories resulted from a detailed and systematic interpretation of the data in which they had previously spotted some relevant themes, established patterns, and found the commonalities among the information obtained by means of the different methods they had chosen.

More than a mere description of findings, the analysis of the data in each degree work revealed the researchers’ interpretation and discussion of the relationships among themes with relevant support from an array of authors and research projects. In addition, it was perceived that in this section of the reports there was a constant acknowledgement of the participants’ voices, placing them, their life experiences, and their views regarding different topics at the core of the studies. In fact, some of the researchers did use literal phrases to name the categories of analysis and to show their participants’ perceptions more accurately.

Another outstanding issue in this exploration of the novice teacher researchers’ formative research studies is the connotation that language had. In their works, it was a common feature that language was not viewed as the end, but as the means for learners to convey meaning, establish social relations, share their views of the world, and make sense of what surrounded them. In addition, the student-teachers perceived language as a means for reaching their goals as educators and as a local practice, a social activity rather than a structure, a part of social and cultural life rather than an abstract entity, and the possession of a social group (Pennycook, 2010). In relation to that, the English language was viewed as part of the responsibility of the student-teachers as EFL teachers since it was related to the development of the language and literacy of their learners; nevertheless, they emphasized that the English language was only a code, a practical realization of their conception of language.

Either in their reflections, in the literature review, or in the design of the pedagogical content of their projects, the student-teachers mentioned learning through language, rather than learning about the language; to move from mechanical transactions to real communication, and to reach a higher level of interaction, discussion, and analysis inside their classrooms.

In connection to the views of language, the student-teachers displayed some critical considerations about the roles of teachers and learners. They reflected upon the possibility of transforming their teaching practices by considering language as a means for social construction, for the empowerment of learners to take active part both inside and outside the classroom, and for taking into consideration the social context in which they and their learners were immersed. Thus, it was found that they saw themselves and their pupils as social transformers willing to construct knowledge, rather than as passive people who were there to reproduce sanctioned patterns and ideas.

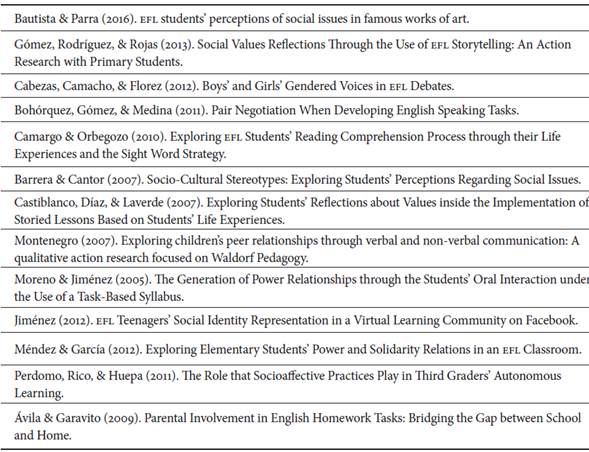

The list of monographs in Table 6 constitutes a non-exhaustive sample of the type of research experiences thought of, designed, and implemented within a transformative and critical framework. The complete manuscripts corresponding to each title can be consulted in the library of Universidad Distrital.

Concluding Remarks

As a way to answer the question posed for the study, it can be said that the implementation of trans-formations mediated by pedagogical and research agendas, such as the ones shown herein, were alternatives with high levels of sensitivity towards the socially associated issues in language education. They were alternatives that led the participants to perform as teachers without using infallible recipes, typical of traditional models (Whitmore & Goodman, 1996). The concept of language education was transformed by adopting a reflective-critical approach, where the student-teachers took an active, participatory, and critical position (Kincheloe, 2004). They evaluated their beliefs about language, teaching, and learning.

Piñeros and Quintero (2006) suggest introspection as a way to link abstraction and meaning making about different types of knowledge. While the student-teachers were constructing their knowledge about language, teaching, and learning, they felt the need to take a stand either for or against educational theories. The student-teachers’ positions served the purpose of informing their decision-making for the benefit of their learners. “Problem posing”, then, became more important than “problem solving” in the study. Posing problems, which was driven by the search for alternatives to the “banking” system of education (Freire, 2002), became illuminated by a view of education that sees curriculum as a life experience and not only as an array of academic spaces (Quintero, 2003).

Another remark that can be made here is that the trans-formations mediated by pedagogical and research agendas took the shape of articles written by the student-teachers during and after the teaching practicum. Table 7 shows some examples of those articles.

To conclude this article, the study reported here served the purpose to add understanding about the participants’ pedagogical and research experiences as forms of intellectual activism and high levels of sensitivity towards the socially associated issues in language education.