Introduction

Many factors influence language learning, and learning strategies play a significant role in this process. Researchers in the area of learning strategies have posited that there is a close relationship between high strategy use and high achievement or success in language learning (Griffiths, 2003; Oxford, 1990). On the one hand, successful language learners, who have been referred to as effective, efficient, good learners, or high achieving learners, are the learners who reach the ultimate goal, which is language learning; according to Rubin (1975), good language learners take advantage of all practice opportunities; they have a strong desire to communicate, they are not inhibited, they practice, they monitor their own and the speech of others and they attend to meaning. Rubin also noted that such characteristics depend on a number of variables that vary with every individual. On the other hand, poor, ineffective, unsuccessful, or low achieving learners are the learners who fail to learn or move relatively slowly through an English program (Vann & Abraham, 1990). The use of learning strategies can aid the learner in being successful, and it is a factor that differentiates high from low achievement. Researchers have explained that high achievers and low achievers use different types of strategies and at different frequency rates (Chamot, Barnhardt, El-Dinary, & Robbins, 1999; Rubin, 1987). Chamot et al. (1999) indicated that “differences between more effective learners and less effective learners were found in the number and range of strategies used, in how the strategies were applied to the task; and in whether they were appropriate for the task” (p. 166). Nonetheless, there are learning strategies that both high achievers and low achievers use in a similar way. Learners bring to language learning such strategies from their previous learning experience. Pressley and Woloshyn (1995) identified strategies which are used for different tasks and across disciplines of knowledge and called them general learning strategies.

Learners engage in English lessons with a wide repertoire of learning strategies that they use across different learning contexts or across different language levels. Such strategies have been proved effective, and they are fixated on the learners’ repertoire. Learners use them as the core strategies of their learning; however, low achievers might be using these strategies incorrectly. It is possible that although both types of learners use the same strategies, they both use different processes. Thus, a learner might be using an adequate type and a significant number of strategies, even at a high-frequency rate; however, they might not be using the strategies efficiently.

The ultimate goals of this study are to identify the strategies that high and low achievers use; additionally, to identify the strategies that both types of learners use in common and the strategies that they use differently.

Literature Review

Research on language learning strategies has been active for decades, and Rubin (1975) was a pioneer in the research of the methods or strategies that good language learners used to become successful. Since then, much research has been conducted in identifying the strategies that good, successful, effective, advanced learners use (Gan, Humphreys, & Hamp-Lyons, 2004; Griffiths, 2003, 2013; Wong & Nunan, 2011).

Researchers in the field of language learning strategies have provided varied definitions of a learning strategy; however, Griffiths (2013), in an exhaustive review of previous literature, defined strategies as “activities consciously chosen by learners for the purpose of regulating their language learning” (p. 36). Although her definition accurately defines a learning strategy, a learning strategy can be not only an activity but also a behaviour that learners acquire, maintain, or change in language learning. When behaviour becomes conscious, it will probably work in a similar way as those activities that are deliberately selected; for instance, being persistent, or responsible during learning. Thus, for the purpose of this study, a language learning strategy is an individual action or behaviour consciously and deliberately chosen by a learner in order to understand, retain, retrieve, and use information in language learning. Additionally, Oxford (1990) states that learning strategies make language learning: “easier, faster, more enjoyable, more self-directed, more effective, and more transferable to new situations” (p. 8). That is, learners choose procedures to learn based on the easiness to perform the activity and the enjoyment they find in the activity, which eventually will aid their motivation and endurance in language learning.

Many learners’ individual differences must be taken into account the use and acquisition of strategies. Learners choose strategies according to their preference, learning styles, motivations, goals, and so on; however, it is not sufficiently clear on what basis learners choose and use certain strategies, and why they prefer them instead of others (Gu, 2005). Perhaps research should be conducted on the reasons learners choose strategies and identify the purpose learners have in mind when using a strategy; thus, the effort can be applied to the intended learning goals.

Rubin (1975) stated that the characteristics of good language learners very much depend on variables such as target language proficiency, age, situation, cultural differences, and learning style. Poor or good performance in language learning can also depend on factors such as motivation, learning style, attitude towards language learning, personality type, and learning strategies, among others. The use of learning strategies has helped in identifying successful and unsuccessful learners. For instance, Chamot et al. (1999) indicated that “differences between more effective learners and less effective learners were found in the number and range of strategies used, in how the strategies were applied to the task; and in whether they were appropriate for the task” (p. 166). Chamot et al. observed that different types of learners apply the strategy differently to the task and that learners might not be accurately applying strategies to the task. Choosing the correct strategy to reach their intended goal is a differentiating factor between high and low achievers. However, learners are not always aware of this choice, and the effect a strategy has on their learning. Learners use strategies based on what they perceive as useful, enjoyable, or practical for their learning and hardly ever is it an informed choice. That is, they do not know the beneficial effect a strategy has, or does not have, in their learning goals.

Low Achievers

There is not a single factor that accounts for low performance but an accumulation of variables over time that hinders achievement. Many factors cause learners to be low or high achievers; such factors can be physiological or psychological, which might be multidimensional in nature (Chakrabarty & Saha, 2014). Low achievers are commonly seen as less proficient, less effective, or unsuccessful learners; they are usually categorized as learners who obtain a low grade on an exam or a course. Vann and Abraham (1990) defined unsuccessful learners as learners who move relatively slowly through an intensive English program. Similarly, Wen and Johnson (1997) defined low achievers as learners who spend more time learning English and with lower scores. The slow motion through a course that Van, Abraham, and Wen explain in their definitions of low achievers can lead the learner to quit before reaching their learning goal. That is, they are less likely to complete a language course. However, slow progress in a language course does not define a low achiever. A learner can have slow progress, yet he or she can still be learning.

Normazidah, Koo, and Hazita (2012) outlined the characteristics of low achievers. They state that low achievers see English as a difficult subject to learn. They depend on the teacher as an authority; they lack support to use English in an environment outside the classroom; they lack exposure to the target language; they have a limitation of vocabulary, and they lack the motivation to learn English, which causes a negative attitude towards the learning of English. The view of Normazidah et al. regarding low achievers seems to comprehend, mostly, individual attitudes and motivation towards language learning. That is, with the correct spur of motivation, learners can look for ways to expose themselves to language, ways to increase their vocabulary, and take a proactive attitude towards learning. Alderman (2008) points out that poor performance comes from a lack of motivation, effort, and effective learning strategies. Learners’ attitudes and behaviours towards language learning can have a great impact on their performance. Chang (2010) offered a more simplistic factor to low achievement; she explained that some of the weaknesses in language learning come from learners’ attitudes to learning such as laziness. Although it cannot be generalized, laziness can be derived from a poor motivation to invest effort in activities, and it can be caused by the perception learners have of their learning experience; for instance, boredom, unwillingness to work, or unattractiveness to what they are doing. Thus, high achievement does not only come from high strategy use but from attitude, motivation, and perceptions or behaviours in learning.

Additional to the great importance of motivation, several factors can be accounted for success in language learning. Samperio (2013) suggests that for a learner to achieve success in language learning, three factors need to be present and interact with each other. In the first instance, a learner must be motivated to learn and to adopt adequate behaviours in learning. The power of using their own will to change behaviours in benefit of learning can change the course of learning. Duckworth and Seligman (2006) call this power volition and they describe it as the capability to inhibit distracting behaviors in order to attain a higher goal. Samperio also states that language learners need time to engage in a proactive behaviour outside the language classroom to practice the language and to expose themselves to language learning. Finally, he states that a learner must have a repertoire of strategies to choose from to solve language tasks.

Taking the initiative to pursue goals rather than remain passive and expecting teachers to provide all learning is necessary for language learning. Early research conducted by Rubin (1975) explained that good language learners take responsibility for their own learning. That is, they take the initiative in terms of what they want to learn which is decisive in being successful. Macaro (2001) states that “one thing that seems to be increasingly clear is that, across learning contexts, those learners who are proactive in their pursuit of language learning appear to learn best” (p. 264). Being in control of what learners want to learn can give them the chance to take advantage of the opportunities readily available, therefore, deploy more and varied learning strategies to reach their goals. Learners’ proactive behaviour can help them become self-regulated, autonomous, and motivated learners, which, in turn, will lead them to use different methods and adopt different behaviours in language learning.

Work Conducted on High and Low Achievers

Much research has aimed at discovering what successful learners do (Chamot et al., 1999; Griffiths, 2003, 2015; Rubin, 1975) so that the strategies they use can be taught to low achievers. However, there is also research conducted on the strategies that low achievers use and ways to help them improve strategy use. Findings have postulated that high and low achievers use different types of strategies and at different frequency rates. For example, Zewdie (2015) compared the language learning strategy use among high and low achievers. He discovered that both high and low achievers use similar types of strategies. The difference he found was in the time they invest for studying. He stated that high achievers spend time more wisely; that is, they invest and manage their time in a strategic way. For example, they distributed their practice over multiple times while they monitored their performance. Similarly, Rajak (2004) investigated the learning strategies of low achieving learners of English as a second language (ESL). Although his findings indicated that low achievers reported an interest in learning English, which is an important factor in both learning and strategy use, their overall results demonstrated that the low achieving learners used learning strategies with a moderate frequency. The average of the frequency of strategy use was not higher than 3.5. Oxford (1990) defined an average above 3.5 as a high frequency of strategy use; this suggests that low achievers do not use strategies frequently enough to boost them to a high achieving category. Boggu and Sundarsingh (2014) investigated the language learning strategies among the less proficient learners by means of the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL). Their findings indicated that the less proficient learners used compensation and memory strategies more frequently than cognitive, metacognitive, social, and affective strategies. In a similar way, Tang (2015) discovered that high and low achievers vary considerably in metacognitive strategy use. High achievers have a more proactive and metacognitive behaviour, and they are able to use more often strategies such as self-monitoring, planning, setting goals, seeking practice, and overviewing in reading; self-evaluating, paying attention, and identifying information. Tang concluded that a metacognitive strategy-training program for language low achievers would greatly improve low achievers in language learning. Teaching learners how to use learning strategies can motivate learners to not give up and endure in language learning (see Dougherty & Kienzl, 2006; Jadal, 2012; Luo, 2009; Yang, 2010).

Low and high achievers differ in many aspects; however, both types of learners need to respond to their current learning situation and manage their learning in the most accurate way. High and low achievers can be similar in other ways; for example, the fact that they use learning strategies. Whether they are strategies from their strategy repertoire or strategies that they can deploy at the moment of facing a new task, both types of learners use mechanisms to help them in the language learning process.

Method

The study followed a mixed-methods approach methodology in which quantitative data were gathered from a questionnaire, and qualitative data gathered from individual interviews.

Participants

The participants were university learners and people from the general community; that is, a variety of different types of learners, from homemakers and high school learners to already professionals such as doctors, engineers, or lawyers. Their ages ranged from seventeen to sixty years old. They all belonged to the first level (out of six) of the English language course. The sample consisted of 27 learners with a high score and 30 with a low score on the achievement test score. The English achievement test consisted of 151 items, therefore, percentiles and quartiles of the achievement test scores defined categories of learners. High achievers (HA) were classified as learners who obtained 118 correct answers or above on the achievement test; in contrast, low achievers (LA) were learners who obtained 89 correct answers or below on the achievement test.

The Strategy Questionnaire

Numerical data were collected through the questionnaire developed by Martinez-Guerrero (2004) which comprises a selection of activities and tactics in learning from different methodological-theoretical approaches in learning strategies and self-regulation. The questionnaire explored the strategies learners, who are about to start studying university, had in order to predict academic success in learning. The questionnaire included four theoretical dimensions. The first dimension is called behaviour and organizational strategies, and it is composed of study (STU) and study organization strategies (STO). The second dimension is called cognitive and metacognitive strategies and included the concentration (CON) and the cognitive (COG) strategies of the questionnaire. The third dimension named motivational and affective strategies included achievement motivation strategies (AM) and affective strategies (AFF) and the fourth dimension is called cooperative and interactive strategies, which comprise cooperative learning strategies (COO) and interaction in class strategies (IIC).

The questionnaire, in Spanish, was adapted to the specificity of the language learning context by adding the particles: English, in the English class, or when studying English. For example, original Item 1: “When I read, I can identify main information of the text.” The item was adapted to language learning in the following form: “When I read English, I can identify main information of the text.” This procedure allowed contextualizing general learning strategies in language learning.

Interviews

Adding a qualitative element in the form of individual opinions, attitudes, reactions, or beliefs complements and extends the quantitative findings of the questionnaire data. Interviews had as the main purpose knowing the learners’ real use of strategies in English learning from the perspective of their genuine experiences. The questions were mainly designed to figure out how learners deal with learning tasks such as daily studying, studying for exams, strategies they use to overcome difficulties, and strategies they use out of the classroom in order to improve their language learning. Another objective was to find out the perception of difficult areas in language learning and the strategies they use to improve in such areas. It was also intended to seek learners’ strategies they use to improve in reading, speaking, listening, writing, and memorization, and the activities they use to improve language learning outside the classroom.

The Achievement Test

The English achievement test consisted of 151 items, and the publisher of the textbook in use provided it. The number of correct answers was considered for statistical analysis. The achievement test included sections that tested listening, social language, reading, writing, and sub-skills such as vocabulary and grammar. Items included true and false, multiple choice, and cloze sentences with word banks from which learners could choose. It also included items that required more thought and more productive responses than just choosing, for example, answering questions, completing conversations, or cloze sentences in which students would not benefit from a bank of answers. The test also included items that required critical thinking such as inferential understanding of language and ideas in context from reading passages.

Results and Discussion

The Learning Strategies That High and Low Achievers Use

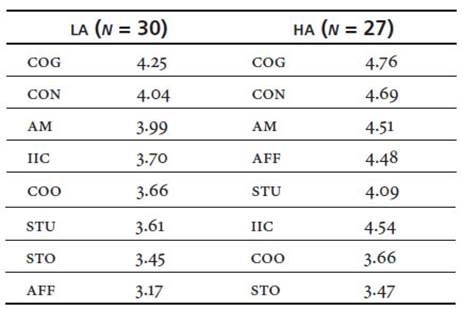

The HA group was associated with a more frequent use of strategies (average = 4.33). In the same way, the LA group was associated with a less frequent strategy use (average = 3.86). When strategies were computed into categories, it was possible to observe that HA show a higher average score than LA in all categories of strategies. Table 1 shows averages of strategies computed into categories of HA and LA.

To the naked eye, averages of HA on Table 1 suggest that they use strategies at a higher frequency than low achievers; nonetheless, in order to know if the difference in strategy use between low and high achievers is statistically significant, a t-test for independent samples was applied to data. Results indicated that study (STU), concentration (CON), cognitive (COG), achievement motivation (AM), affective (AFF), and interaction in class (IIC) strategies showed a statistically significant difference in strategy use between high and low achievers. That is, high achievers, indeed, use such strategies at a higher frequency rate. Nonetheless, study organization (STO) and cooperative (COO) learning strategies do not show significant differences. This result suggests that low achievers and high achievers use STO and COO strategies at a similar frequency rate. In other words, HA and LA use these strategies at low-frequency use.

Strategies Used by High Achievers

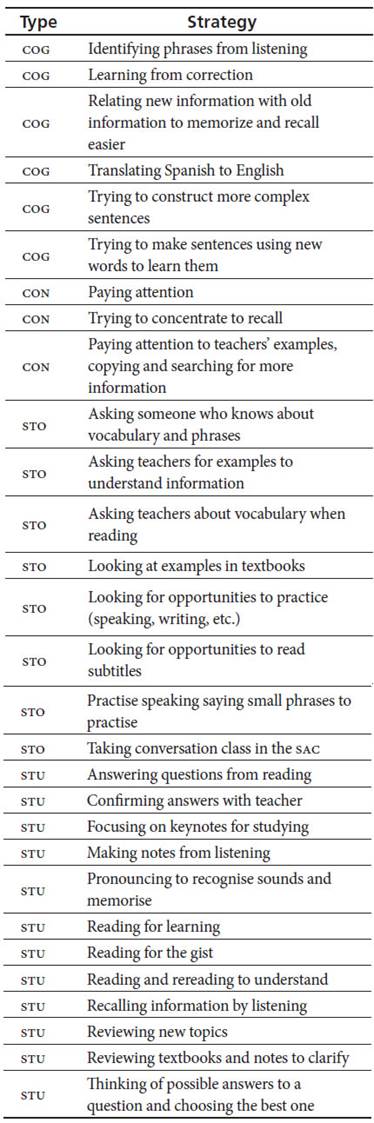

Figures in Table 1 show that HAs use COG, CON, and AM strategies at a higher frequency rate and, to a lesser extent, STU, IIC, COO, and STO strategies. On the contrary, in data gathered from interviews, it was found that HA reported using a number of STO and STU strategies, which are not measured in the questionnaire. Interviewees reported strategies such as asking teachers for examples to understand information, identifying phrases from listening, learning from being corrected, looking for opportunities to practice speaking and writing with friends, making notes from listening, paying attention to others’ mistakes to learn, trying to construct sentences that are more complex. They also mentioned trying to make sentences using new words to learn them, watching movies, and observing grammar and pronunciation. The STU and STO strategies gathered from interviews counter the low-frequency rate of the STU and STO strategies included in the questionnaire. That is, interviewers choose from their repertoire of varied strategies the one that best suits their needs and is the most adequate to reach their learning goals.

It was observed that the study strategies that HA use in language learning principally help learners in reviewing and revising information. For example, learners review by reading and rereading in an attempt to recall information so that they can understand and retain it better. Pozo (1990) defines reviewing and revising as recirculation strategies; particularly, strategies that help learners recall, and eventually, acquire information; and which learners use across learning contexts. Pozo’s interpretation contrasts with that of Himsel (2012) who sees reviewing (as reading) as a rote learning strategy; namely, the memorization of information based on repetition. He argues that such strategy does not have a beneficial effect on learning. For Himsel, rote methods involve shallow processing because such methods result in very limited brain change: Methods that do not generate enough raw materials to construct an accurate memory. Instead, he suggests cognitive processes used to learn such as encoding information; however, he warns that not all of the encoding processes are equally helpful. Interestingly, Evelyn, a 17-year-old high school interviewee, implied that reviewing is a characteristic of good learners. When she was asked what she did to study; she stated, “Since I am a student, what I do is I take my book and review.” Evelyn’s perception of students represents learners’ procedures to store information. Furthermore, language learners hold a positive view on reviewing and use it as an effective strategy.

High achievers also reported using strategies that aid them to understand and practice the language, for instance, looking for unknown information, which they use to clarify meaning with someone more knowledgeable such as teachers or more experienced learners. Apparently, learners are aware of their knowledge and are able to evaluate what they know and where they need to improve. When learners come to recognize that they need to improve, they move their attention to a different path and look for strategies that suit their needs.

High achievers mentioned looking for opportunities to practice speaking with native speakers, family, or friends or even by themselves and attending conversation classes in the self-access center, and so on. Looking for opportunities to practice or looking for unknown information suggests a degree of metacognitive and self-regulated behaviour since they are able to monitor their understanding. This finding suggests that language learners make use of metacognitive strategies. The use of metacognitive strategies incorporates the ability to predict, plan, evaluate, and monitor knowledge efficiently and accurately; and they can facilitate and accelerate the whole process of transfer of strategies from one language (L1, L2) to the other (Wenden, 1999); additionally, it enables learners to achieve knowledge. Griffiths (2003) implies that metacognitive strategies are correlated with proficiency and high frequency strategy use. Learners are able to retrieve their metacognitive knowledge from their previous learning experience, which is stored in the long-term memory (Phakiti, 2006). Possibly, achievement motivation strategies are supported by a metacognitive behaviour which is the spark for the use of more and different strategies, and which learners have transferred from previous learning experiences.

In a similar way, HA reported strategies to practise pronunciation such as reading in silence to memorize or repeat aloud many times. This result concurs with Cohen’s (2011) categorization of language use strategies. Cohen makes a differentiation between language learning strategies and language use strategies. He explains that language use strategies allow learners to use the language that they have in their current interlanguage. In a deeper categorization, Cohen divides language use strategies into retrieval, rehearsal, cover, and communication strategies. The main intention for learners in using rehearsal strategies is to practice new material to learn it, to store it in memory for a later retrieval.

Interviews provided a great number of strategies that extends and complements quantitative data. The strategies used by HA show that they are able to evaluate their needs and deficiencies in language learning and take action in improving them. HA can be metacognitive in their learning, and they are aware of their strengths and weaknesses. They understand that success depends on the effort they make and the strategies they implement.

Strategies Used by Low Achievers

Quantitative analysis indicates that LA, similar to HA, use cognitive (average = 4.25), concentration (average = 4.04), and achievement motivation (average = 3.99) strategies at a more frequent rate and study (average = 3.61), study organization (average = 3.45), and affective strategies (average = 3.17) at a less frequent rate. A difference between HA and LA is found in the frequency of use of strategies.

Contrastively to quantitative data, qualitative data suggest that LA interviewed mostly reported using STU, STO, and COG strategies; and to a lesser extent, CON strategies. Language learning at an adult age demands consistency and effort to master the language, and study and study organization strategies represent the effort learners make. LA interviewees use STO strategies such as deliberately allotting time to studying, and within this time they reported attending the self-access centre and looking for opportunities to practise, mostly speaking with friends, native speakers of the language, and classmates; listening to music, radio, or the news; and watching TV or movies. LA also reported looking for clarification when the information was not clear. LA look for approaches that deepen their understanding of the language, and they use strategies that could actually make a big difference for learners; for example, attending the self-access centre which provides learners with varied materials and opportunities to practice their language skills.

Similar to HA, LA frequently reported using STU strategies such as reviewing and reading or rereading strategies as a way to study, making lists to memorize, repeating to memorize. The use of these study strategies seems to be a common process they use to approach learning in any context. However, the activities around the strategy of reviewing might be the differential factor between HA and LA, for example, reviewing and then trying to restate what was read in your own words or trying to explain the material to someone else, or even make notes, or mind maps.

Oxford (2011) calls these series of strategies “chain” strategies. Strategies stored in the learners’ repertoire do not work in isolation; Oxford stated that strategies work in “chains” and Macaro and Wingate (2004) in “clusters”; for instance, listening to songs in the target language. This strategy involves a series of activities or tactics and behaviours that a learner would need to implement in order to have an actual benefit from the strategy. For example, the learner will likely pay close attention to the song; she will identify unknown vocabulary, and she will look for the meaning of the words. Then, she will listen to the song again and pay attention to the new vocabulary. She will identify the pronunciation and try to imitate the pronunciation of the singer. In these activities, she will adopt a tolerant and patient behaviour. Perhaps many other activities will take place when listening to songs. Additionally, strategies seen as chains of activities transform along the process of using it every time the learner approaches a skill or uses a strategy consciously and purposefully. Thus, when learners purposefully listen to songs the next time, strategies will likely be different. The choice for different strategies can change according to the results learners obtain, and their interest to invest effort in learning. The use of strategies to reach a goal represents the effort and interest learners have in their own proactive attitude towards language learning. LA seem to invest time in STU strategies that help them rehearse information they see in language classes.

High Achievers and Low Achievers

Findings in the research of language learning strategies have established that a difference between HA and LA is the frequency of strategy use (e.g., Green & Oxford, 1995; Griffiths, 2003; Şimşek & Balaban, 2010). Findings indicate that HA make use of a great number of strategies at a high-frequency rate. HA use 29 strategies included in the questionnaire at a high-frequency rate. In contrast, they use nine strategies at a low-frequency rate. As expected, LA only use five strategies included in the questionnaire at a high-frequency rate whereas they use 25 strategies at a low-frequency rate.

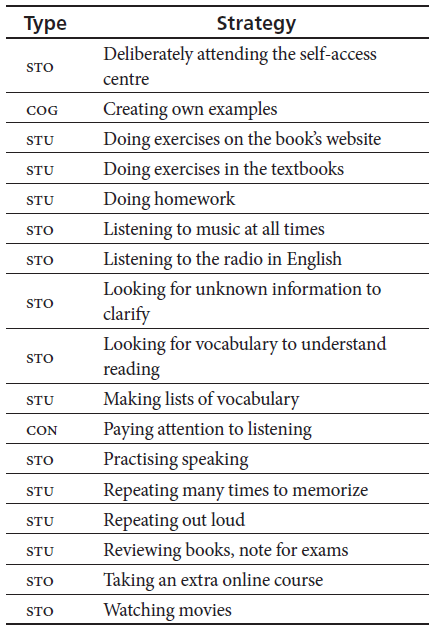

These results appear to support the belief that, in general, high achiever learners report using a higher number of language learning strategies and at a more frequent rate than low achievers or less proficient learners. However, HA and LA concur in the use of some strategies. T-test for independent samples results show that there is no significant difference on strategy Number 9 (“When I solve problems in English, first I try to understand what it is about, and later I solve it”); strategy Number 2 (“When I study English, I try to relate new things that I am learning with the ones I already knew”); 34 (“When I study English in a team with my classmates, we make sure that everybody in the team learns the topics well”), and 19 (“When I study English, I organize the material by topics to analyse them one by one”). According to Green and Oxford (1995), these strategies, reportedly used at similar rates of frequency across all levels, are called “bedrock strategies.” As stated by Green and Oxford, these strategies “contribute significantly to the learning process of the more successful students although not being in themselves sufficient to move the less successful students to higher proficiency levels” (p. 289). A list of strategies that both HA and LA use emerges from qualitative data. Table 2 shows a list of strategies used similarly by HA and LA.

Although high and low achievers use some strategies equally, as previously discussed, a difference in strategy use resides in the chain of activities around the strategy used as well as the purposes for using it; consequently, learners get different outcomes. For example, in watching TV, what learners do much depends on the purpose; that is, if the learner wants to improve pronunciation, the activities that the learner will participate in will be different than if the purpose in watching TV is learning vocabulary or improving grammar. High and low achievers can spend different levels of effort, and the number and the type of activities will consequently be different. An example of this is Jacobo, who is a high achiever. He reported watching TV in order to observe grammar and pronunciation; that is to say, Jacobo clearly stated the purpose of the strategy (observe grammar and pronunciation). In contrast, Susana, a low strategy user, watches TV with subtitles in order to understand; however, she does not state if her goal is understanding reading or listening; however, activities performed will likely change for any case. Another example is Lilia, a high achiever. Lilia reported watching TV without subtitles to force herself to understand, and she tries to identify phrases or vocabulary when listening. Lilia’s purpose of using the watching TV strategy (identifying phrases or vocabulary) can contribute to developing her listening skill. In contrast, most of the LA who reported listening to music did not state the purpose of using it.

The discovery that HA and LA use similar strategies raises questions regarding pedagogical practice. Do learners purposefully use strategies, or do they mechanically use strategies without a purpose in mind? Further research needs to be conducted to clarify the extent to which learners use strategies with a purpose in mind. Ideally, a learning strategy is purpose oriented; however, at times, learners are unaware of the purpose they have in mind while they use a strategy; an example of this is watching TV with the purpose of learning vocabulary. If the learner strays in listening comprehension, pronunciation, and the enjoyment of the TV show, the learner will unlikely improve vocabulary. Perhaps knowing the purpose for using a strategy could greatly improve the efficiency of a strategy since effort would be directly applied to the learning goal. Thus, watching TV to improve pronunciation, to identify grammar, to learn vocabulary, to practice listening comprehension, or to assess comprehension would considerably help the learner reach the learning goal. It would be, then, necessary not only to encourage LA to include strategies that HA use but to make sure that LA use them correctly. However, future research needs to be conducted in order to observe whether these strategies will expand with practice and will be part of a repertoire of strategies more typical of a high achiever.

Just as there are strategies that both groups use, there are strategies that HA use as opposed to LA. Perhaps these strategies contribute to greater learning in HA. Table 3 shows the strategies that HA reported and which LA did not.

It should be noted that HA use a higher number of cognitive and concentration strategies, which belong to the cognitive and metacognitive dimension of the strategy questionnaire. These frequently used strategies appear to set the HA apart from LA. The inclusion of an important number of strategies found on the cognitive and metacognitive dimension support the idea that metacognition is essential in language learning proficiency. Learners who are able to manage their performance on a task can perform better, and their learning can be more meaningful. Metacognition is developed in learners in the context of their current goals and can enhance their learning. Additionally to the variation between using a strategy purposefully, or not, by HA and LA, above described, a number of strategies that HA use differently from LA arises.

Among the strategies gathered from interviews, HA use study, study organization, and cognitive strategies more frequently (see Table 3). Considering the varied possible factors that contribute to language learning, one can see it is possible to hypothesise that the strategies that HA used, above listed, seem to contribute to the learners’ process of learning and higher language achievement. The inclusion of these strategies as a means of managing learning indicates that HA use strategies to process new information, rehearse and retain new information as well as strategies that allow them to manage studying habits such as looking for opportunities to practice or manage their study time.

It is possible that at beginning stages of language learning, learners have not fully developed language learning strategies, and possibly they use strategies they have in their repertoire which might not be appropriate for language learning; for instance, reviewing while they need to develop oral skills. With the development of language knowledge and the complexity of language tasks, learners will require using a greater number of strategies and more focused strategies in language learning instead of the general learning strategies that they bring from their general learning contexts; for example, strategies for pronunciation, speaking, or listening. Possibly, beginner learners transfer the strategies from their repertoire because language tasks have not required learners to deal with different strategies that more advanced language tasks require.

The finding that HA use strategies which LA do not, suggests that such strategies contribute to their proficiency, achievement, or success; however, it is not feasible to generalize this finding. The purpose of using the strategy towards a goal is a differentiating factor in the effectiveness and ineffectiveness of strategies. For example, if watching TV to improve listening comprehension were the case for LSU, the subtitles might be of much help in understanding. However, much of the information understood in the TV program comes from reading subtitles and not from listening. Therefore, if learners assess the use of the strategy based on the obtained results, they will be misdirecting effort in a skill (reading) with the intention of improving another (listening).

A high number of strategies do not always imply a benefit in learning. An example of this is Ofelia, Aleli, Milagros, and Karla, who were not able to reach high achievement scores despite their high strategy use in language learning. It is important to acknowledge the reasons why (and how) a strategy can be useful. Although different types of learners use the same type of strategies, they work differently on every learner; consequently, they obtain different results.

The relationship of high strategy use-high achievement appears to have exceptions, and it can only be speculated that learners are using strategies that are not having any beneficial effect on their achievement and that they might be wasting effort in using them. What makes learning strategies contribute to the learner’s language learning processes lies in the strategic adaptation to tasks directed by their goals, and the frequent use of strategies; the larger the variety of strategies is the higher the possibility to direct effort accurately to learning.

Conclusion

Learners use strategies from their repertoire of strategies in their early stages of language learning, and it expands and revolves around the practice into strategies that help learners to become less dependent as they reach higher levels of language learning.

The inclusion of study strategies intended for the practice of the language may well reflect the reality that many learners are in need to rehearse and evaluate their learning; however, learners would need more than practice to be proficient language users; they need strategies appropriately directed to their needs and lacks. Thus, it is necessary to acknowledge that learners learn differently depending on different factors; consequently, they choose various learning strategies. Then, we need to encourage learners to identify the purpose of doing what they are doing and assessing their methods for learning to address effort accurately.

Several factors, internal and external, come together and cause learners to use strategies. Research has shown that motivation, metacognition, and self-regulation are important characteristics in differentiating low from high achievers. However, motivation has been found responsible for self-regulatory decision-making (Corno, 2001). In consequence, numerous studies have revealed a significant relationship between motivation and language learning strategy use (Oxford, 1996). The lack of adequate motivation can interfere with an effective adoption and orchestration of strategies and behaviours necessary for successful language learning.

Findings of this study support the idea that low achievers might be incorrectly addressing effort to unneeded areas without having a positive or significant effect on their learning. Green and Oxford (1995) suggest that strategies that poor learners use are not necessarily unproductive but that they may not work adequately in their learning process. The strategies used by LA do not necessarily suggest that the strategies are bad or wrong. Instead, it possibly reflects LA would need to include more, and more frequently, strategies used by HA to improve their success without the necessity to change their repertoire or discard the strategies they use.