Introduction

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, English has gained increasing importance worldwide, and as the international language that it is claimed to be, it is expected to promote economic, social, and individual benefits. Some of those benefits include: the insertion of the national economy into the global market as a result of people’s enhanced communication skills that allow carrying on business with foreign companies, as well as access to better job opportunities. Consequently, educational institutions in Colombia, language programs, as well as teachers, have put forth an effort to innovate English language teaching (ELT) by actively adopting teaching trends that help respond to the mandates of the Ministry of Education (MEN). Among these trends, communicative language teaching (CLT) is a dominant approach, which is regarded as an option that contributes to the achievement of the main goal set in Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo (PNB, National Bilingualism Plan). This goal refers to the development of communicative competence (speaking, writing, listening, and reading skills) in the English language in all educational contexts, from pre-school to higher education (MEN, 2004).

However, these assumptions about English have been challenged by critical scholars (Janks 2014; Luke, 2012; Mora, 2014) as they consider them dominant discourses that promote English as the only language of success. In addition, other aspects such as the development of learners’ criticality, reflexivity, and their exercise of social agency using the target language have been scarcely encouraged, simply because learners are just taught to communicate in the target language (L2) without questioning the underlying messages and power ideologies conveyed through the L2. In this regard, Pennycook (2001) warns that English in a global context would generate unequal power as well as wealth distribution unless English teachers and learners address social issues and, in this way, go beyond the walls of the classroom or, in other words, extrapolate social agency to the world outside the classroom.

Teaching and learning English from this perspective requires a number of transformations, though. On the one hand, the way language teaching has been conceived, as a list of grammar items to be taught (Ko & Wang, 2013) would need to be changed for critical literacies, which advocate for the incorporation of students’ realities as part of the texts to be addressed and reflected upon in the English class (Duncan Andrade & Morrell, 2008; Mora, 2014; Rincón & Clavijo, 2016). Thus, students’ involvement in class discussions and in the creation of counter texts, for instance, calls for a view of language as a whole, in which myriad structures and vocabulary would be demanded by students to fully engage in class. In this same vein, the materials traditionally used in English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching are called to attention from this perspective as they usually fail to represent students’ realities and continue to address issues alien to students’ culture.

Theoretical Background

Critical Literacy

Critical literacies are not new among scholars and researchers in literacy education. However, due to different theoretical bases, there is no unique definition of “critical literacy” (Green, 2001). In their broadest sense, critical literacies refer to the ability to read texts going beyond their superficial meaning. That is, it implies approaching texts in a reflective way to understand working ideologies (Luke, 2012) such as power (Janks, 2010), inequality, and injustice (Comber, 2015). In the realm of critical literacy, text is understood as a “vehicle through which individuals communicate with one another using the codes and conventions of society” (Robinson & Robinson, 2003, p. 3). Texts, in this sense, can be either songs, novels, poems, conversations, pictures, movies, and so on.

To develop a thorough understanding of the tenets of critical literacy, McLaughlin and DeVoogd (2004, p. 54) elaborated four principles which are: (1) critical literacy challenges common assumptions and values; (2) critical literacy explores multiple perspectives, and imagines those that are absent or silenced; (3) techniques that promote critical literacy are dynamic and adapt to the contexts in which they are used; and (4) critical literacy reflects on and uses literacy practices to take action for social justice.

Hence, the critical literacies approach is generally contrasted with “functional literacy”. The former views literacy as a social practice (Gee, 1999), while the latter views literacy as the mastery of linguistic skills. In addition, Manning (1999) developed a framework to distinguish critical literacies from functional literacy by establishing the difference between their respective ideology purpose, literacy curriculum, and instruction. On the one hand, the main objective of functional literacy is to produce skilled workers for the marketplace. Consequently, the curriculum is restrictive and the instruction is individualistic and competitive. On the other hand, for critical literacies, texts are not neutral but marked by power messages, dominating interests, and hidden agendas (Janks, 2010, 2014). In order to deconstruct these texts and unveil their ideological messages and power relationships, the curriculum is to employ materials from the everyday world as text and analytic tools.

Critical Literacies in Action

Critical scholars have overtly supported the idea that there is not a single procedure for incorporating critical literacies into the classroom (Luke, 2012), given that the particularities of the context where the foreign language is taught differ from one another. Thus, an approach to critical literacies “needs to be continually redefined in practice” (Comber, 2001, p. 274). In this realm, Behrman (2006) identified six classroom applications of critical literacies instruction in order give a snapshot of the many possible ways of doing critical literacies in different educational settings. These practices are:

Giving students the opportunity to read texts that supplement the traditional classroom texts such as works of fiction, nonfiction, and texts derived from the popular culture so that they can explore and interrogate social issues.

Exposing learners to the reading of multiple texts written by different authors on the same topic, allowing students to recognize that there is not a unique meaning or interpretation of a text, but rather multiple perspectives that are inherent to the authors.

Encouraging students to read from a resistant perspective. That is, a reader may have different perspectives of a text depending on the lens from which it is approached, namely gender, language, sexuality, class, or religion.

Allowing students to write counter narratives as personal reflections on the topic that is being learned. Through those counter texts, they can express their thoughts, perceptions, and feelings.

Promoting student-choice research projects in order to link the topics mandated by the curriculum with those of learners’ personal interest. In this way, students will be more in charge of their own learning while bringing to this process their everyday lives.

Moving students to take social action and take their everyday issues to the world outside the classroom. Hence, they can start recognizing literacy as a powerful tool for social change.

Some of these classroom practices have been identified in the Colombian context ranging from elementary school to university level. For instance, Arias (2017) implemented a critical media literacy (CML) approach into the curriculum with the purpose of promoting young English students’ critical reading of media, specifically related to food. As a result, students were aware that the media can present a distorted version of reality and therefore, they expressed deception (feeling “tricked”) towards familiar food ads.

Similarly, Rincon and Clavijo (2016) incorporated the tenets of critical literacies through a multimodal approach with a focus on the model of community-based pedagogies with the intention of providing high school students with the opportunity to explore social and cultural issues in their neighborhood. Results of this study suggest that through the use of multimodality, students reflected on the issues that permeated their own lives and on local cultural practices.

At the university level, Alarcón (2017) implemented a critical intercultural approach in an English outreach program to promote intercultural communicative competence among English learners. In this study, students were exposed to materials that presented world realities, which helped them develop critical consciousness, social and language skills as well as engage in a process of reflection and action.

The Use of ELT Materials in the Critical Lessons

Even though there is a vast array of publications in the field of critical ELT, little has been done regarding material development in this area. Therefore, to respond to this need, Rashidi and Safari (2011) expounded a model for critical ELT materials. Some of those principles are explained next.

First, whereas traditional ELT materials only focus on developing learners’ communicative competence through the discussion and understanding of superficial topics, resources developed in a critical language teaching aim at helping learners to move “beyond the superficial to a more complex understanding of the realities” (Rashidi & Safari, 2011, p. 254). Therefore, Rashidi and Safari (2011) recommend that language materials in the critical language class should aim at fostering learners’ communicative abilities while, on the other hand, these resources offer learners the opportunity to apply these communicative abilities in context so that they become aware of the social issues around them as well as be empowered to act on these issues. Second, and aligned to Vasquez’s (2017) ideas, the topics presented in these materials should be related to student’s daily lives and experiences as well as their interests. In this way, both students and teachers may be able to engage in considerable analysis and discussion of these topics (Rashidi & Safari, 2011).

In addition, the topics addressed in those materials should also be related to students’ native language (L1) culture since to get a deeper understanding of the world and globalization, it is first necessary to take “greater account of the local and respecting its value and validity” (Canagarajah, 2005, p. xiv).

Lastly, in order to address issues tied to the L1 culture compared to the target culture, the use of different sources of information, such as authentic materials (Burnett & Merchant, 2011; Kellner & Share, 2007; Saunders et al., 2016) should be considered. This includes commercials, cartoons, and social media in which reading, writing, listening, or speaking can be combined and applied in specific activities. Thus, these sources help learners acquire the information in L2 as well as demonstrate how they identify themselves and differ from others (Reagan & Osborn, 2002). In sum, the inclusion of students’ culture and interests in the classroom, as well as the utilization of a wide range of materials, seem to encourage learners to go beyond the superficial meanings of texts while at the same time foster their language development.

Context of the Study

This research project was carried out in an English class of the language center housed at a private university in Medellin, Colombia. The English program is offered as a requirement for undergraduate learners from different majors to obtain their professional degree. It has been established that students ought to take and pass ten academic levels of English in order to get their diploma.

Five important principles define the methodology and the learning and teaching processes of the language center. These include social constructivism, differentiated pedagogy, the competency-based approach focused on learners’ action, autonomy, and the ICT (information and communication technology) appropriation.

There were 18 students in the class where this research project took place (although only 14 were present during data collection), nine women and nine men from 19 to 40 years old. All of them were undergraduate students, pursuing different majors, including visual design, fashion design, architecture, theology, social communication, chemical engineering, mechanical engineering, and business administration, among others. Most of them had already finished their studies, and some had even finished their trainee internship. Additionally, some students from this course came from different regions of the country.

Along with the participants were the two authors of this paper: Catalina, the English teacher and researcher and Claudia, the research advisor. Both researchers were responsible for planning lessons intended to foster learners’ language skills and helped them use English to interrogate and observe multiple perspectives regarding social issues such as gender violence and discrimination. In the classroom, Catalina worked as a guide and a monitor of students’ reflections and discussions about the topics that they addressed. As researchers, it was in our interest to understand what would happen if undergraduate students also had the opportunity to learn English from a critical stance and addressed social issues that would enable them to exercise their critical reflexivity while learning the target language. We also were interested in understanding what was entailed for a language teacher to teach from a critical perspective.

Method

This study is inscribed in a critical paradigm, in which “reality is socially constructed” (Richards, 2003, p. 38) and as such, learners bring their own life experiences and world perspectives which help with meaning negotiation through interaction with others. In this way, they have the opportunity to engage in a dialogical relationship that may facilitate them to unveil power messages and raise awareness in such a way that they are empowered to question and disrupt oppressive structures, which was one of the purposes of this study.

Moreover, critical research focuses on the impact of various educational approaches that privilege “attention to critique and to social justice as much as it does the development of sanctioned academic skills” (Morrell, 2009, p. 99). Thus, an instrumental case study design was followed, since it allowed us to “investigate a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context” (Yin, 2003, p. 13). In addition, this case study used different sources of information to collect “detailed, in-depth data” (Baxter & Jack, 2008).

Data Collection

Data collection protocols included interviews, focus groups, teacher’s field journal, questionnaires, and students’ artifacts. These protocols provided sufficient information to understand how students’ participation in critical lessons impacted their language learning, what they and their teacher gained from this experience, their struggles, and overall, the implications of incorporating critical literacy principles in this particular context. As follows, an overview of each protocol used is described.

Interviews. Two students who represented opposing reactions towards the pedagogical intervention were interviewed at the end of the implementation. These interviews aimed at understanding where these reactions could stem from.

Focus groups. A focus group was held at the end of each phase, whose primary purpose was to provide information about students’ ideas, analyses, and reflections during the implementation of this pedagogical intervention. Additionally, they helped us find out whether students found this critical approach relevant for language learning.

Teaching journal. Keeping a journal was useful for different reasons: Firstly, it provided information about students, the way they were interacting, their performance in class and level of engagement which, together with the analysis of other sources, helped to select the participants to be interviewed. Secondly, the journal helped us to modify some aspects of lesson planning. Finally, it also supported the teacher’s continual self-reflection not only as a researcher, but also as a teacher moving towards teaching English from a critical stance.

Questionnaires. Two questionnaires were administered during this intervention which also served as self-assessment tools with which learners could judge their performance and reflect on the critical and linguistic components of the lessons.

Students’ artifacts. Two samples of learners’ work were collected which allowed us to further analyze learners’ reflexivity as well as their language development.

Unit Design and Implementation

To carry out this project, we designed a pedagogical intervention for which some of the activities were prepared and adapted following different online sources like The Gender, Language, & Sexual (In)Equality Research Group (http://gentext.blogs.uv.es/), and the Center for Media Literacy (2009). Similarly, in order to achieve the critical objectives set for each of the units, some of the questions proposed by Janks (2014) and McLaughlin and DeVoogd (2004) were used. For instance, whose viewpoint is expressed? What does the author want us to think of? How might alternative perspectives be presented? What action might you take on the basis of what you have read/viewed?

The topics for this implementation were selected based on the fact that at the time of the implementation, trending social issues related to gender violence were of major interest in the national media. In addition, as most learners came from different regions of the country, Catalina considered that it was appropriate to design the second unit to explore the concept of diversity and the different forms of discrimination that we may encounter in our social reality.

For the first part of this pedagogical intervention, Catalina explored how gender and domestic violence were presented in different texts (visual and written) as well as to identify and problematize factors that contributed to violence against women around the world. Thus, after analyzing comics, news stories, a Disney video segment, and a music video portraying visual and text messages concerning gender and domestic violence, learners were given the opportunity to express their ideas and opinions about such images. Additionally, strategies such as group work, debating, switching perspectives, creation of counter texts, creating campaigns, and giving presentations were used to allow students to show and negotiate their understanding of these issues in the target language.

Some of the critical objectives established for the second part included visualizing and reflecting on multiple perspectives of people involved in issues related to discrimination (victims and perpetrators); as well as to become aware of the importance of appreciating people’s differences and the need to disrupt stereotypes in order to stop discrimination. Therefore, to align these objectives to the language content of the course, students used different grammar structures to explore and analyze a poem, a song, a video containing Hollywood representations of Latin people, and to identify and deconstruct their own stereotypes. For this unit, role playing, group work, class discussions, storytelling, writing of a reaction paper, the creation of a blog, and “stand and deliver” activities were carried out.

At the end phase, a focus group and students’ self-assessment procedures were conducted. In this part, students reflected on both their perception toward their linguistic development and the topics covered during the lessons. Moreover, assessment strategies were applied throughout the implementation of the units to check students’ learning and use of the grammar concepts covered. To do so, Catalina created two rubrics for assessing final assignments. Among the criteria established for assessing those tasks there were content, sentence structure, and vocabulary.

Data Analysis

To analyze the data collected, we took into account different steps, as proposed by Thomas (2006). First, information from the two questionnaires and journal entries was gathered and information from the two audio recordings of focus groups and interviews was transcribed. Then, the data were read and analyzed inductively by assigning short names/codes to chunks of information containing similar ideas from the different sources. From these codes, some themes were established based on recurrences and were contrasted against the research question (What does it take for a teacher and EFL university students to engage in critical literacy practices?) Constant comparison of the information collected from different sources, grouping, coding, triangulating, tabulating, and categorizing were the steps taken to identify categories.

Findings

Data collected revealed that students and the teacher experienced a variety of challenges and gains related to students’ language use, their perceptions of critical content, and the teacher researcher’s journey.

Perception of Language Use

One of the most recurrent struggles students experienced during the implementation of this pedagogical intervention corresponded to language use. This was due to the fact that, traditionally, students are presented with specific language points and vocabulary to be learned and practiced throughout the lessons, as though communication involved the use of only one language structure and limited vocabulary. Therefore, when trying to convey their ideas in English, in a class discussion, students felt inhibited as they needed a combination of grammar structures and vocabulary they did not feel confident about, which hindered their participation. Evidence of this was provided in the following quote: “I couldn’t express myself in different ways. I mean, grammar” (Rafael, Questionnaire).

To illustrate this idea, in one of the interviews, one student commented:

My idea was not to respond in Spanish but in English. This is perhaps the reason of my inhibition. As speaking English is somewhat hard for me, I sometimes felt limited to participate. I mean, I had the idea in my mind but I didn’t know how to express it.1 (Juan Camilo)

Consequently, during the discussions, Catalina assisted learners with the vocabulary they needed and translated the ideas they expressed in Spanish into English. Moreover, for the discussions held in the second part, she allowed some time for learners to work in small groups and think, organize, and express their opinions about the topics, beforehand, which helped students to cope with class discussions in an effective way.

Conversely, even though the use of the target language was a constraint for students, they were also aware that, in fact, they learned and used new vocabulary and grammar during the implementation of the critical intervention. In this respect, one of the participants noted:

The topic itself is appropriate for using all we have learned in terms of grammar. So, I think I can now do that after having learned English this way during these days. (Carlos, Focus group)

Similarly, students’ language development was also seen in their class outcomes (see Figure 1) in which they used a variety of vocabulary and grammar structures to express their viewpoints about different topics, moving away from the traditional grammar drills usually promoted in the language class.

Furthermore, students valued the fact that they participated in these activities in contrast to the lessons they had traditionally been exposed to, which is reflected in the following excerpt:

Teacher, I think that the approach you have used this week has helped us a lot because the best way to learn English is by needing it and using it. That is, using the traditional approach is like repeating the structure. So, we don’t learn much if we compare this to the times when we use the language to express our own ideas and develop certain topics. (Andrés, Focus group)

Data also revealed that students were able to use not only the language they had already learned and were learning in the course, but also they could go beyond the mere utilization of language for conveying superficial meanings. In other words, they valued the importance of both learning the target language in context, and addressing issues that were socially and culturally relevant.

At the beginning I thought I was going to learn English similar to the traditional way, such as “the house is green”. But at the end we did something much bigger because we didn’t learn just the phrase “the house is green”. On the contrary, we could express our viewpoint regarding issues such as gender violence and discrimination. We learned how to put that phrase in context and then we could talk about diverse issues without following the repetition exercise. This helps one take a different perspective towards the world. (Juan Camilo, Interview)

All in all, during the implementation of this intervention, language was used for different purposes. This proves that even though students and even the teacher were anxious about meeting the communicative and linguistic goals of the course while engaging in critical conversations, these goals were achieved throughout the different activities.

Perceptions of Critical Content

Data collected suggest that the topics addressed in class were not only of the interest of many learners but also related to their realities. Thus, in the questionnaires, 8 out of 14 students stated feeling identification with the topics:

I really liked the topic. I felt completely identified. But it was sometimes hard to remember or think about issues that are still hurting for me. (Laura)

I have been a victim of discrimination due to my skin color and my coastal roots. So, I think it is really nice to address this [topic] in the course since it is a problem I have to deal with every day. (Andrés)

Moreover, this personal identification with the content was also evident in the mixed feelings some learners experienced while developing the activities. For instance, after carrying out the activity “stand and deliver”, one of the students who was later interviewed stated:

With the question I identified the most was when you asked “have you been in a situation in which a person is being discriminated or being mistreated and you haven’t done anything about it?” I stood up because I had been in that situation. But the reason I felt identified with that question was not because I didn’t want to help that person, but because I couldn’t. The idea of not being able to do anything to help that person is still hurting. (Rafael, Interview)

This evidence reveals that topics addressed in class were not alien to learners but related to their L1 culture, which made them relevant to them.

Additionally, data indicated that 9 out of 14 learners felt moved to propose alternatives to combat problems such as gender violence and discrimination: “Due to my life experience, I have always wanted to help women who are or have suffered like I did. I would love to do something more for them” (Laura, Questionnaire). She explained that as she had been a victim of violence, she felt reluctant to remain silent or to ignore this issue. Moreover, motivation to take social action was not confined to the walls of the classroom as noted in the teacher’s field journal:

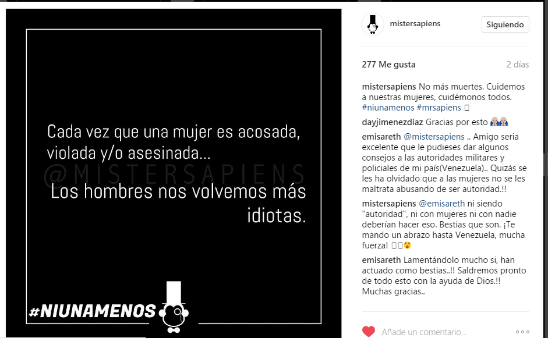

One of the students, who has an active participation in social media, made a post about violence towards women. We had previously addressed this issue in class. In his post, the student let male followers know about the importance of breaking stereotypes . . . Later that week, he kept posting messages reflecting against femicide.

Even though Andrés’ post was not in the target language (see Figure 2), his reflection in the social media proves that he decided to take actions beyond the walls of the classroom and as such, exercise his role as an active member of the society, committed to social transformation.

Subsequently, data also showed that students were also aware of the role that education plays in fighting against these issues: “Through these dynamics I could learn to promote education as the main tool to fight these issues” (Andrés, Questionnaire). In a similar vein, learners perceived that the discussion of these problems in class helped them become aware of their role as active agents in their society:

Teacher, I consider that by tackling issues such as discrimination and diversity, we can make other people aware of the importance of respecting and treating those around us in a better way. (Felipe, Focus group)

Nonetheless, some other participants in this study demonstrated opposing reactions towards the critical component of these units.

I felt somewhat inhibited due to the fact that the topic is alien to me. So, it was hard for me to put myself in other people’s shoes. This is why I couldn’t contribute much to the discussions. (Ricardo, Questionnaire)

Here, Ricardo shows that as a result of not perceiving himself as having identified with the topics, he felt inhibited to participate in the critical conversations held. Moreover, one of the students felt annoyed and reluctant to participate in the conversations: “I didn’t feel identified with the topic because even though I would like this problem to stop, it is an issue that makes me feel uncomfortable” (Luisa, Self-assessment).

Learners’ struggles were also evident when they were asked to contradict stereotypes that exist in our culture. This was not only perceived by me, as a teacher researcher, but also by other participants of the study, as exemplified in the following excerpt:

Teacher: What was that issue that you observed in your classmates?

Rafael: The thing is that there are some who had like a narrow mind while there are some others who have an open mind. Like, “whatever happens, it is normal”. For example, one of my classmates said like “one can’t fight against stereotypes because they are something that is fixed and seen as normal.” However, through the activities we carried out I could realize that it was possible to change that perspective. In fact, if I contribute . . . maybe I will make a difference. (Rafael, Interview)

Reasons why participants found it difficult to contradict stereotypes might be due to the fact that these are rooted and tied to their cultural identities, as they have been infused since childhood.

Furthermore, data also indicate that students’ resistance to the critical component of the lessons came from the fact that some of them are still used to adopting a passive role in the learning process. Therefore, some students experienced difficulty in moving to a more participatory role:

Teacher, I think that the teacher’s contribution is necessary. I say this because during that week, the contribution was mostly made by us, right? And it is really nice. However, the part of the teacher or the contribution by an expert as knowledgeable about the topic was missing. (Juan Camilo, Interview)

In sum, data revealed that being involved in these critical lessons had a variety of effects on students, from identifying with the issues discussed in class and becoming active citizens, to even resisting the content of the lessons.

Teacher’s Journey: Challenges and Struggles

Difficulties experienced by Catalina took place when planning and implementing the lessons. Firstly, planning was very challenging:

I have the big challenge to move from the traditional role of an English teacher who instructs and promotes communicative competence among learners, to a more critical position, in which a wide range of social issues are questioned and analyzed. (Journal entry)

In fact, Catalina did not know where to start, what questions to ask, what resources to use, and even what topics to address. This, considering that important social problems, for instance, are rarely present in textbooks.

Secondly, it took Catalina a while to value sources such as news, videos, cartoons, and media related to students’ own culture as sources teachers can use and adapt to prepare and hold critical conversations. Hence, when planning she had to be cautions not only in selecting the material, but also in designing activities that attracted students’ attention and helped them reflect critically on those issues. Moreover, Catalina was concerned about keeping a balance between the communicative and the critical content of my lessons:

I have had a tough time finding the material and resources to support my classes. I fear that in the process of applying these lessons, the linguistic content that I have to teach (based on the curriculum) might be disregarded. (Journal entry)

Furthermore, designing tasks to assess the critical and communicative content of the units was also puzzling; Catalina had to carefully plan assessment tasks that helped learners reflect and express their stance about the issues addressed in class while considering the criteria to assess the linguistic content. This concern was also present during class development:

It seemed that [students] felt more willing to talk about something they knew and was of national interest. The conversation was very engaging. Nonetheless, the same as yesterday, language use was a constraint for learners to freely express their thoughts. I had to guide them and rephrase what they wanted to say. I personally think that for future lessons, a little more class time to analyze language use should be devoted. (Journal entry)

This quote reveals that during the implementation of the units, Catalina experienced certain insecurity concerning the way she had planned the lessons, especially when considering the linguistic and communicative content.

In addition, Catalina also experienced an internal battle regarding the way she managed the critical component of the units with students in the class. That is, even if learners found it hard to contradict stereotypes and propose alternatives to fight stereotypical categorizations against different minority groups, she experienced the same difficulty:

When we discussed stereotypes about people from other regions of the country, students and I found it difficult to refute them and offer a different perspective . . . it was frustrating for me to be unable to help them refute most of the stereotypes we have created. (Journal entry)

According to Thoman (1978), disrupting a fixed stereotype is not easy because “people perceive selectively through the screen of their own particular attitudes, values, beliefs, and especially personal experience” (para. 4). Perhaps if Catalina had anticipated some arguments to help learners break out these stereotypes, this struggle would have been overcome more easily.

In fifth place, during the class discussions and the activities carried out with the group, Catalina struggled not to be neutral. Thus, she felt a certain lack of confidence when learners asked her to share her personal experiences. This insecurity is exemplified in the following journal entry:

I have been thinking about what I am going to tell my students or the position I will adopt in class when I discuss this topic with the group. . . . My intuition tells me that if one aims to become a critical teacher, it is first necessary to heal one’s wounds first and stop keeping a neutral stance, as if nothing touched you. However, I find it hard to let them know about all I have been through. (Journal entry)

The uncertainty was then lived inside the classroom, particularly during the “stand and deliver” activity. Soon after this activity concluded one of the students asked “Teacher, do you feel identified with any of those sentences?” Catalina felt somewhat uneasy with this question because she thought that if she had let them know about her experiences with issues of discrimination it would have been like a teacher showing her weaknesses to the students. Catalina just answered, “Yes, I felt identified with some of the sentences” and she quickly moved on to another activity to avoid more questions.

Finally, it bears mentioning that Catalina also felt challenged and somewhat frustrated by some learners’ resistance towards the critical components of the units. That is, there were moments during the implementation when she felt some internal anger, especially when some students expressed not feeling attracted to the topics addressed because they found it more as an ethics seminar than an English class. This frustration is evidenced in the following journal entry:

There was one student (who had earlier in the units expressed his unconformity with the critical topics) that when working with the teams asked me “teacher when will we finish with the ética and valores class?” At that moment, I couldn’t feel more disappointed and ashamed. (Journal entry)

It is important to point out that the activities proposed in a critical language class do not have to please everyone. However, Catalina could not stop herself from feeling frustrated with students’ resistance which might be due to the fact that she had not anticipated this. Therefore, it is imperative for teachers, particularly novice teachers, to understand that being critically literate does not consist of shifting or rejecting particular viewpoints, but of considering and examining multiple perspectives, social identities, and discourses (Janks & Morgan as cited in Alford, 2001). Perhaps if Catalina had been fully aware of this idea, she would not have experienced the feelings of discouragement and frustration when encountering this issue in some of her classes.

Personal and Professional Growth

Not everything in this process was challenging and puzzling. Professional and personal gains occurred all throughout this process. As a teacher researcher, the first gain refers to motivation and commitment to accomplish the challenging endeavor of undertaking critical literacies in the language class. Despite all the challenges and struggles Catalina underwent, they did not discourage her. In fact, she became aware that teaching is a political and social act (Nieto, 2013). Thus, it was her responsibility to learn to work from a critical stance and be an agent of change.

Therefore, as a teacher at the university level, she felt and still feels that she has the responsibility to educate citizens able to transform our society and ultimately, help them disrupt and interrogate multiple messages that have been presented to us as universally true.

In addition, there were moments of discovery and surprise during this planning stage which led Catalina to question the mainstream values people are exposed to since childhood. The following notes exemplify this idea:

I have been a fan of Disney’s films since I was a child. However, I never stopped to think critically on the way this type of media portrays the role of women in our society. . . . What shocked me the most was the fact that I always ignored the messages behind these “beautiful films”. (Journal entry)

Moreover, surprise and personal identification occurred through interaction with learners; listening to their contributions, Catalina could see a different perspective of the topics discussed: “It was amazing to see how they interpreted the messages they observed in the comics I presented. In fact, some of them saw different and deeper messages that I had failed to perceive” (Journal entry).

Thus, Catalina confirmed that in critical literacy, learning is bidirectional; she understood that in critical literacy teachers are called to downplay their authoritative role (Giroux, 1987), and as such they must be sensitive and attentive to different aspects, which can be identified through interaction, observation, and dialogue with learners (Nieto, 1977).

Conclusions

The development of the communicative competence for EFL learners is not left aside by critical scholars. That is to say, critical literacy does not disregard linguistic and communicative components of the curriculum, as has been contended (Bacon, 2017; Huang, 2011; Kuo, 2014). Instead, a critical approach to English language teaching focuses on helping learners becoming aware of the connection between language and their social, cultural, and political lives. Hence, it is key to give students the opportunity to explore, interrogate, and discuss texts, materials, and topics that are related to their L1 culture. Nevertheless, it is paramount for teachers to assist and help learners convey their ideas in the target language allowing them to feel more confident to participate in class discussions. In this regard, many of the strategies traditionally used in the communicative competence-based curriculum might prove convenient.

Considering that some learners might be resistant to the critical components of the lessons, one sees they may find it hard to change their long-held beliefs, and ultimately exercise their social action. Thus, it is advisable for teachers not to expect total success from the first task of implementing critical literacies in their classrooms and to understand that this is a process that takes time and effort.

Although this research study focused on an isolated attempt to bring critical literacy to the EFL classroom, these findings agree with those of other Colombian educators interested in teaching languages from a more critical perspective and interested in moving from a role of “passive technicians” to that of “transformative intellectuals” (Kumaravadivelu, 2003), thus contributing to educational progress and social transformation. This endeavor, however, should not be relegated to teachers as individuals; to commit to such enterprise, teachers should try to work together as a teaching community and consider different teachers’ views (Renner, 1991). As a result, they will collaborate and devote to “the creation and implementation of forms of knowledge that are relevant to their specific contexts and to construct curricula and syllabi around their own and their students’ needs, wants, and situations” (Kumaravadivelu, 2003, p. 14). Joining efforts in these attempts to bring critical literacies to the classroom might come as a first step to impact curricula at large and begin the social transformation that is so needed in Colombia.

Finally, if higher education institutions and policy makers aim at educating citizens who are social and change agents, then the curriculum should reconsider and transform the roles that teachers and learners have traditionally adopted in the classroom. If such transformation occurs, more opportunities for students to construct knowledge from their experiences as well as unveil and question power messages infused in our society are provided. To achieve this, language teachers should be given the time and support to explore and incorporate critical perspectives into language teaching. As a result, teachers will be more empowered and more aware that they too have the right and the responsibility to make decisions in curriculum construction.