Introduction

The need of professional development and the creation of a professional development program not only for full time professors, but for adjunct instructors, who are the most representative population among instructors in a public university in Colombia, inspired this case study. Final reports of professors who had passed their provisional years at this university (Pineda Hoyos, 2011; Pineda Montoya, 2013), the evaluation of a multilingual program (Gómez Palacio, 2014), preliminary findings of a case study (Pineda Montoya, 2015), and the context evaluation about the reading comprehension program at the university (Quinchía Ortiz, Muñoz Marín, & Sierra Ospina, 2015) also inspired this work.

Coaching as a professional development strategy became a tentative strategy to provide adjunct teachers with opportunities for professional learning because as it is expressed by Velásquez Arboleda and Bedoya Bedoya (2010) in their study about adjunct teachers’ factors of psychosocial risks, pay-by-the hour instructors lack time to enjoy their spare time due to their long hours of work. As a consequence, educational institutions should not expect adjunct instructors to have time for long hours of training sessions but instead, they should think about alternative professional development opportunities for them, such as coaching that can be performed in private sessions.

Therefore, with the assumption that adjunct foreign language instructors do not have enough time to attend long hours of training sessions, four strategies of professional development were proposed in 2013 in a professional development program at the public university: mentoring, coaching, chats, and training sessions (Gómez Palacio, Álvarez Espinal, Gómez Vargas, Riascos Gómez, & Gil Guevara, 2016).

The instrumental case study (Stake, 1995; Stake as cited in Creswell, 2007) we examine in this article was carried out during a year and a half with the aim to explore if coaching, one of the strategies offered in the professional development program at the outreach section of the university, works as a professional development strategy for adjunct foreign language instructors. Therefore, the following questions guided our experience:

Theoretical Framework

Professional Development

The professional development program in the outreach section of the Colombian university from 2013 until 2015 followed this definition of professional development inspired from the works of Diaz-Maggioli (2003), Head and Taylor (1997), and Lozano Correa (2008):

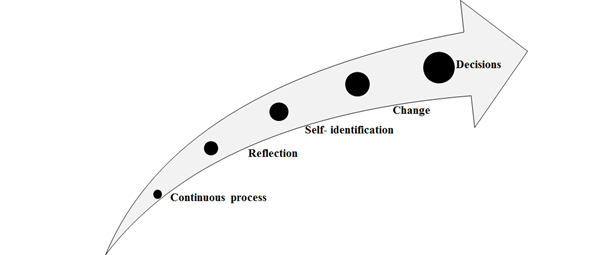

A continuous process in which a teacher makes reflections, thinks about his/her teaching practices, identifies his/her abilities to perform different activities, and what he or she is capable to learn by himself or herself in order to voluntarily make changes in his/her teaching practices. In this process, the teacher discovers his or her true professional self-something that cannot be carried out without the firm awareness that a shift must be made in his/her professional inner self and not only as a result of external agents’ influence. (Gómez Palacio as cited in Gómez Palacio, Álvarez Espinal, & Gómez Vargas, 2018, p. 547)

Figure 1 illustrates the process.

Diaz-Maggioli (2003) points out that professional development is an “ongoing process” in which teachers “engage voluntarily” and find opportunities to learn, so they can adjust their teaching practices to their students’ needs. He considers professional development an “evolving process of professional self-disclosure, reflection, and growth” (p. 1) that combined with communities of practice and “job-embedded responsibilities”, show results over time.

Diaz-Maggioli (2003) also emphasizes that for professional development to be successful, research on teachers’ needs should be done. He also examines different needs of professional development considering that teachers’ professional development also depends on the career stages in which teachers find themselves. Therefore, he suggests different approaches to professional development, which should be explored taking into account that teachers at different career stages may differ on their professional needs.

Regarding Head and Taylor (1997), they define professional development as a continuous process in which “change and growth” take place having in mind that teachers are always asking themselves how to become “better teachers”. They place emphasis on the premise that this is a process “centred on personal awareness of the possibilities of change and of what influences the change process” (p. 1). In addition, they consider it is a “self-reflective process” because it is “through questioning old habits” that teachers will identify new versions of themselves and their performances. Head and Taylor highlight that professional development focuses on “individual needs”, and it is valued and developed in different ways considering teachers’ workplaces and their specific expectations for development.

Coaching

Coaching still has an uncertain origin in time, country, and discipline (Ortiz de Zárate, 2010; Ravier, 2005). It is multidisciplinary according to Brock (as cited in Krapu, 2016). In addition, it is a discipline that needs research (Latham, 2007). However, coaching is considered to have great possibilities as a professional career in the near future (Brock as cited in Krapu, 2016). If we go back to ancient Greece, philosophers such as Socrates performed similar practices to what North American, European, and Latin American coaches have performed so far. It means that coaching has emerged from contributions of different practitioners who, in some cases, have come from academic and non-academic settings (Brock as cited in Krapu, 2016). Socrates, for example, used questions among his followers, and that is a particular practice in coaching. Heidegger, existential philosopher, who states that human beings should set up goals and follow them because human beings are finite, promotes part of the coaching strategy, that is, setting goals (Ortiz de Zárate, 2010; Ravier, 2005).

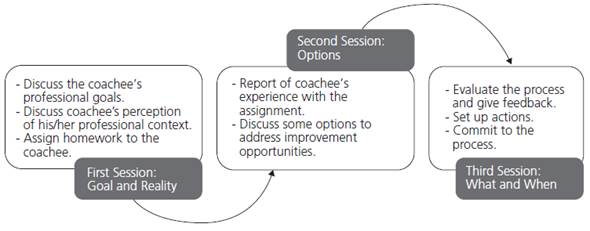

Whitmore (2009) states that “coaching is unlocking people’s potential to maximize their own performance” (p. 10). He promotes the GROW model (Goal, Reality, Options, and What and When) as the model coaches should follow during a coaching session. The International Coaching Leadership in Colombia (2011) defines the GROW model as Goals, Reality, Options, What and Will. In the Goal stage, coachees set short and long term goals. To examine the Reality, it is indispensable to explore the situation at the present time. Options refer to the different possibilities the coachee has and the strategies that he or she can use. What involves the actions, the performers, the commitment, and the will to achieve what has been set.

Both Clutterbuck (2007) and Goldvarg and Perel de Goldvarg (2012) as well as Whitmore (2009) agree that coaching happens in conversations. All of them also concur that a coaching session is performed with a coach and a coachee, the two main characters in a coaching session. Goldvarg and Perel de Goldvarg (2012) and Whitmore (2009) highlight that the purpose of coaching is to make a person conscious and responsible for his/her own actions.

Lozano Correa (2008) emphasizes that every professional should go deep inside himself or herself to find his or her real self. She promotes coaching because it is a tool that contributes to people’s personal and professional growth. It is an activity that is developed between a coach and a coachee. In addition, she lists three types of coaching: personal coaching, business coaching, and coaching for education. Personal coaching or life coaching focuses on people’s personal issues or concerns. Business coaching is developed in three steps. In the first step, the coach helps the coachee identify improvement opportunities. In the second one, the coachee’s paradigms are questioned through the process and the coach’s goal is to invite the coachee to change blocking paradigms. On the third and last step, the coachee commits to actions.

Bou Pérez (2013) points out that all definitions about educational coaching highlight the human being as the principal actor in personal growth; therefore, he invites all the educational system actors to rethink the educational system transforming the “learning to learn” attitude into necessary competence to manage change in order to accomplish stated goals (p. 15). Lozano Correa (2008) considers “the practice of coaching” necessary at any personal levels. She states that “the practice of coaching” helps people analyze what they are doing, their reality; it guides them to become more creative, and to learn how to solve obstacles they might encounter (p. 133).

Coach

According to Whitmore (2009), based on what participants in his courses have expressed, a coach is “patient, detached, supportive, interested in people, good listener, self-aware, attentive”. It is a person who has “retention and perception”, and he or she is always aware of what is going on. It is a person who has technical expertise, knowledge, and experience, which is the foundation to gain credibility and authority (pp. 51 - 52).

Catalao and Penim (2009), for example, have a set of questions for coaches’ self-assessment. With the questions, coaches can ask themselves about their performance at the beginning of the process when they meet the coachee, and about their practice during the coaching session. Some examples of those questions are found in the Appendix.

Goldvarg and Perel de Goldvarg (2012) and Whitmore (2009) agree that a coach is an expert in coaching, and it does not have to be an expert in the coachee’s professional field. Nonetheless, we want to express that besides the characteristics mentioned by Whitmore, the questions discussed by Catalao and Penim (2009), and the clarification about the coach’s field of knowledge, a coach is a non-professional or professional person who decides to coach others and finds an institution to obtain a certification in how to perform coaching sessions, something that we did not find expressed in this way in the literature. A coach is a person like you and us who is trained to perform coaching sessions. According to Whitmore, a coach is “a detached awareness raiser” (p. 42).

Coachee

A coachee is a person like you and us who has a specific purpose in mind, and in a specific personal area. For example, in this instrumental case study, our participants had to have a professional purpose in mind. We only explored our participants’ professional area. Cubeiro (2011) states that a coachee is a person who is willing to change. It is a person who would like to explore his/her beliefs, show his/her emotions, and commit to actions.

Method

We conducted an instrumental case study (Stake as cited in Creswell, 2007) because we wanted to identify how coaching sessions would help foreign language instructors in their professional development, and what their gains and changes were if there were some. We used “multiple sources of information” (Creswell, 2007, p. 73) such as a questionnaire, coaching sessions, interviews, and coaches’ and coachees’ final reports of the process. Before we gathered the information from the participants, they signed a consent letter in which we explained all the steps and possible results after the coaching sessions.

Setting

The outreach section at the public University is a section in charge of the foreign language courses offered to all students within the University. It is also responsible for the English courses offered to professors at the University whose aim is to learn or to improve the mentioned language. Furthermore, the section is well-known around the University for providing its services to different regions in a department in Colombia where the University is present. The University has offered this service since 1990 when it was officially established. The first semester of 2017, the outreach section consisted of 134 faculty members among which five were tenured professors, 10 provisional professors, and 119 adjunct foreign language teachers, which has always been the most representative population.

Interdisciplinary Research Team

Foreign language instructors and psychologists worked collaboratively on this project. The research team consists of two research assistants in the process of earning an undergraduate degree, two provisional instructors, an adjunct instructor, two psychologists, and a tenured instructor who was the main researcher. Both the psychologists and the main researcher, certified coaches by the International Coaching Leadership in Colombia, were the coaches who ran the sessions in this project.

Participants

Five adjunct English instructors who we called coachees were the participants in this study. By the time we started the study at the outreach section, there were 175 foreign language instructors from which 165 were adjunct instructors, and 10 full time faculty. Six adjunct English foreign language instructors volunteered to participate in the study, and after the main researcher explained to each of them the dynamics of the coaching sessions and the methodology of the study, one of them quit due to personal reasons.

Each of the participants suggested one pseudonym to be called during the study; they were Elena, Julieta, Jazmin, Bambam, and Tom. The five of them represent the adjunct instructors’ population at the outreach section. Two of them are professional translators, one holds a B.A. in foreign language teaching, one is a professional in languages, and the last one holds a degree in an area different from foreign language teaching. According to the information inserted in the database about instructors in charge of the University courses in the year 2017 semester 1, there are 134 foreign language instructors from which 15 instructors are professional translators, 73 hold a B.A. in foreign languages, 20 more are professionals in languages, and the other 14 hold a degree in an area different from the foreign language teaching one. There is one instructor who is in the seventh semester of a major that is not in the field of foreign languages, and 11 instructors do not have their degrees reported in the database (Universidad de Antioquia, 2015).

Data Collection

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was designed based on Creswell (2012) and sent to the participants four months after we reviewed the literature about coaching, and then we decided the objective and questions we were going to ask. One of the objectives of the questionnaire was to find out how motivated our participants were to be part of the face-to-face coaching sessions with our three coaches. We also wanted to know, before the coaching sessions, what our participants knew about coaching and if they really had a professional goal that they wanted to discuss in the coaching sessions, something that was one of the requirements the main researcher explicitly stated when the invitation to participate in the project was sent.

Coaching Sessions

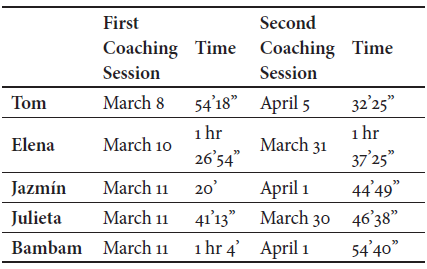

We included the coaching sessions as “new and creative data collection methods” (Creswell, 2007, p. 129). The coaching sessions are private, confidential, and target-oriented conversations between a coach and a coachee (Goldvarg & Perel de Goldvarg, 2011, p. 261). They can last between 90 and 120 minutes (Cubeiro, 2011, p. 27). The coaching sessions performed in our project lasted from 20 minutes to around 2 hours as Table 1 shows.

We planned to have five coaching sessions with each participant; however, we performed two coaching sessions with them; the other three sessions were used to give participants therapeutical orientation carried out by our two psychologists, members of the research group. We also agreed on having the coaching session with each participant and the three coaches (the two psychologists and the main researcher who is a foreign language teacher).

During the first coaching session, the three coaches reviewed with each participant the information registered in the questionnaire, especially the part related to his/her professional goal. At the end of the first session, the coaches assigned homework to each coachee. During the second session, each participant was asked to report their experience with the homework. After the third session, each participant chose one of the psychologists to continue with the process and the three remaining sessions. The first two sessions were audio-recorded; however, we did not record the last three sessions with the psychologists because the focus of those sessions was on personal issues, and the study focused on the exploration of coaching as a strategy for professional development. Figure 2 shows how we applied the GROW model in the coaching sessions in the project.

Interviews

The interviews were performed after the five sessions with each participant. We conducted a semi-structured interview, audiotaped it, and transcribed it (Creswell, 2007). One of the interviewers also took notes. The interviewers were one of the co-researchers and one student assistance. The main researcher was also present during the interviews but as an observer. The interviews were carried out in Spanish.

Data Analysis

We used a traditional data analysis for qualitative research which consists of preparing and organizing the information, then reducing it into themes through a coding process to finally present it in figures, tables, charts, or discussions. This is part of the three analysis strategies stated by Creswell (2007, p. 148). Additionally, we based our analysis on Wolcott’s (1994) recommendations:

Highlight certain information in description

Identify pattern regularities, contextualize in framework from literature.

Display findings in tables, charts, diagrams, and figures; compare cases; compare with a standard. (p. 149)

We also considered categorical aggregation and direct interpretation as types of analysis which are discussed by Stake (1995, p. 78), who encourages the researchers to search for patterns based on the research question and be attentive for unexpected patterns that emerge from the analysis.

We did not transcribe the entire coaching sessions; we only selected the information we needed such as the purpose of the conversation, the assignments left after the coaching sessions, and our coachees’ gains. We did not transcribe the whole conversations because we agreed with the participants in the consent form signed that personal information would not be revealed, and the majority of the information discussed in a coaching session is personal data about the coachee. In addition, our purpose with the development of this instrumental case study has been to identify the coachees’ professional purposes and their gains after a coaching session for professional development rather than to analyze how a coaching session is performed. Both coaches and coachees presented a final report that researchers compared to analyze coachees’ professional purposes and their gains after the use of coaching sessions as a strategy for professional development. One of our research assistants transcribed all the interviews, and the researchers present in the interview also took notes.

Findings

Jazmin, Elena, Julieta, Tom, and Bambam consider coaching as a useful strategy for professional development. They consider it as a professional development opportunity for adjunct foreign language instructors (not only for English instructors) to grow both personally and professionally if trust and genuine interest are involved. We will discuss in the following paragraphs our participants’ gains after the coaching sessions, their definitions of coaching and professional development. In addition, we will explain the role that genuine care and trust play in coaching sessions as a strategy for teacher professional development.

Participants’ Gains

To be part of the research project, each participant had to have a professional purpose to discuss in our coaching sessions. According to the information collected, these were our participants’ professional purposes: Elena wanted to improve, not only her teaching practices, but also herself as a person; Jazmin wanted to improve professionally; Julieta expected to enrich her responsibility and become an example for her students; Bambam wanted to learn how to learn and how to become a better learner; Tom wanted to improve his teaching practices and feel better about himself.

Personal and Professionals Areas

Our participants became aware of personal aspects that they did not control within the class or during their daily routines. Regarding her personal area, Jazmin, for instance, became more confident about her students’ attitude towards her class when she realized, through the coaching sessions, that her students did not leave her class early because the class was not good:

There’s no longer that little voice that tells me: They [students] left because they didn’t like the class. Through the coaching sessions, let’s say that this excessive worry that I was demonstrating for if the class was good or not, improved. (Interview)

Although it seems a simple aspect for an English instructor to take care of, and it may not have any relationship with the traditional view of professional development that is related to her teaching practices; for Jazmin, it was something important that she learned after her reflections through questions because her anxiety diminished; she always thought her students did not like her class; it was her assumption: “I also learned how to reflect through questions in this project” (Interview).

Jazmin learned not to make assumptions about her students’ behavior within the class and towards her class. She gained confidence, and she realized that if she has a doubt about her students’ behavior in class, she should ask.

Regarding Jazmin’s gains in her professional area, she expressed that she learned how to control the time, so it takes her less time to plan a class:

Already there is a managing, already there is a major control of the time of preparation of class for example. (Interview)

Tom gained more confidence (personal aspect) to become closer to his students. He wants to inspire his students, so they can take charge of their own learning process; he would like to empower them.

Wholeheartedly, I want to achieve an excellent empathy with my students and well, motivate them to the point in which they find their own well to progress in their process. It seems to me like a big challenge, and I’m working on that. (Interview)

Tom also became aware of the importance of being organized with grades, attendance, and students’ homework (professional aspects).

Other things I’ve implemented are, for instance, order in the attendance, grading, assign homework in every class, or yes, or being consistent with the assignments, looking for different sources, all of that. (Interview)

Julieta became aware of the words she was using to treat herself and people around her (personal area):

The exercise of judging myself, judging me like, no, like insulting myself, or telling myself stuff like “You are dumb!” “Stupid!”. (Interview)

After the coaching sessions, Julieta started an exercise to be coherent with what she thinks, what she says, and what she does.

In this moment, I’m like doing some exercises that I wouldn’t have done before if it wasn’t because of these coaching sessions. Well, exercises about things like, about something like the coherence of what I think, what I say, and what I do. For example, those kinds of things, that exercise, I never did it before; I’m doing it now. (Interview)

Regarding Julieta’s gains in her professional area, she expressed that since she feels better now about herself, she can be more creative, which impacts her professional life:

When you feel better, you are more creative and obviously, if you are more, a more creative teacher, you will do well in your professional world. (Interview)

Elena, our fourth coachee, became aware of how she has had “the lack of time” as an excuse for everything (personal area):

The psychologist, she was able to identify and tell me, with Claudia as well, “Do not use that much that of ‘I don’t have time’, that predisposition of saying all the time that you don’t have time”. (Interview)

She also became conscious of how much she judges people, situations, and things, and considers the fact of having realized her tendency to judge, an opportunity to become a stronger and better person:

Another aspect that I realized about, like that, like on a general level, was to stop like giving epithets to things, for example. All that seems to me like, it makes you stronger and improves you as a person. (Interview)

Regarding Elena’s gains in her professional area, she expresses that to make changes in her personal area will impact her performance in the classroom:

I am going to contribute to my students with what I have, if I am not patient, how am I going to be patient in the classroom? If I judge, how do I expect students to do not judge me? (Interview)

Bambam gained confidence to start writing again as he used to do many years ago. He expressed that writing was one of his major weaknesses; however, an assignment he did over the study showed the coaches that he used to write very well, something that he had stopped doing because of personal reasons:

I really like that [the coaching sessions] and I have writing in mind, one of my biggest weaknesses. (Interview)

Regarding Bambam’s gains in his professional area, he expressed he would approach more technological devices. He wanted to keep writing with pens and pencils because his handwriting is beautiful; however, he had to accept that to achieve his academic goals, he would have to consider technological devices.

Bambam has had this impediment to write since 1981. His participation in the project made him raise awareness regarding the use of technological devices for his writing and research professional purposes expressed in the first coaching session.

I would like to strengthen my foundations in research. I can talk, talk, and talk about many things and many topics; however, I would like to write about realities in teaching. (First coaching session)

Professional Development From Participants’ Perspectives

Teacher professional development tends to focus on teachers’ development of a technique. Workshops, lectures, courses, and mandatory training are still part of the opportunities of professional development in educational institutions (Diaz-Maggioli, 2003; Hudelson, 2001; Sierra Piedrahita, 2016). Although our participants still recognize the above-mentioned opportunities for professional development in their professional agenda, they also included both personal and professional areas when defining teacher professional development, which they also think should be continuous.

I understand for professional development, is like…a group of activities or a project or a program that aims to improving the performance, in this case, of the teachers, looking not only to their job inside the classroom but other parts of that, like the human part, the personal part. (Elena, Interview)

Professional development is continuous, and it will always be a merging element between the professional human being and society. (Jazmin, Interview)

Basically, professional development for me is the evolution in my field of study, is how I’ve improved. (Tom, Interview)

Well it is any strategy, I mean, it is every kind of strategy or process aimed to enrich you in a professional level, that is, when I say every kind of strategy I mean to everything, that is, not only like that one, that this, a coaching project, no, like, I mean, conferences, everything, everything that helps you, everything, congresses, talks, that help you like to reflect about what you’re doing, if you’re doing it right, if you’re doing it wrong and the negative aspects, improve them, that, for me, is professional development. (Julieta, Interview)

Coaching as a Professional Development Strategy

The participants of the study consider that coaching can be used as a strategy of professional development with all foreign language instructors at the outreach section; it is not only a strategy for English instructors. Coaching is a process in which a person works on her or his improvement areas. Coachees express how much they learned along the process.

I realized that there is a human being behind the teacher. I discovered how emotions play an important role in the classes. (Jazmin, Interview)

With this quote, Jazmin confirms that she cares about emotions in her language classroom. She realizes how important her students’ attitudes towards her class are at the time she evaluates if her class is good or not. Jazmin’s thoughts about her students’ attitudes towards her class reveal issues with Jazmin’s self-esteem.

Elena comments that she gained tools to improve aspects of her personal life:

The process was useful to me to identify some aspects in which I have to go in depth and it also gave me some tools to improve in important areas of my life. (Written report)

For Tom, this process also helped him to learn more about himself and to evaluate himself as well. He considered the experience an opportunity to improve professionally.

The process, in general, was about self-knowledge and self-assessment from my part, to keep improving as a professional in a constant way. (Written report)

As a result of the process, Elena found balance and began to value what she has in life:

As a result from this process, I felt like a liberation and I started a process of “harmony” with my body and my being…is just that sometimes we forget what we have because we are thinking of trifles that damage our health. (Written report)

Bambam liked the process. He felt comfortable and recognized that he made decisions regarding work on academic writing and the use of technological devices.

Very nice, nothing that stressed me, very, everything was right, and very respectful. I liked it, I decided two very interesting things [to use technological devices and work on academic writing]. I felt really well. (Interview)

Genuine Interest and Trust in Coaching Sessions for Teacher Professional Development

Our coachees’ comments regarding trust and genuine interest are shown as follows. They also expressed that our coaching sessions were conducted in an informal and cozy environment that made them feel secure.

It was an easy-going and cordial environment. (Tom)

I felt in an informal environment, and it makes you “let it go”. (Julieta)

Total tranquility without external pressures of any type. (Bambam)

Building trust was excellent. (Elena)

Building trust was present. (Jazmin)

According to Goldvarg and Perel de Goldvarg (2012), in institutions in which coaching sessions are mandatory, to build trust with their coachees is an important coaches’ step. They add that one of the strategies coaches may use to build trust with their coachees is to show “genuine interest for the person not only as an employee, but as a human being with concerns and needs” (p. 53). In our study, coachees were invited to participate voluntarily, and before they signed the consent form, our main researcher explained to them what the coaching sessions were about and what to expect after the process. As a consequence, to build trust and rapport with our coachees was not an aspect our coaches had to worry about. In fact, during one of our research meetings, our main researcher reported that “the two psychologist-coaches had agreed on that the instructors trust was placed on her [our main researcher], and as a result, they see that the process would be easy to carry out”. In addition, one of the two psychologist-coaches’ conclusions was that “the coachees’ trust was placed in our main researcher and what she represented for them at the outreach section”.

Conclusions

The goal of this study was to investigate adjunct teachers’ gains after attending five coaching sessions and see what conditions a professional development program should have in order to implement coaching as a professional development strategy.

Regarding the foreign language teachers of any affiliation, we can conclude that coaching is an alternative professional development opportunity that teachers can consider in their professional development agenda since with the use of this strategy, teachers can get involved in a “process of professional self-disclosure, reflection, and growth” as stated by Diaz-Maggioli (2003). Coaching provides the perfect environment for teachers to grow personally and professionally as Roux and Mendoza Valladares (2014) propose: “teacher professional development is a process of growth that the teacher lives around his/her educational occupation; it helps him/her to improve his/her action, and to understand his/her teaching profession better” (p. 14).

One of the main findings was that coaching provided teachers with an opportunity for professional development in which the theoretical enrichment was not the focus but self-awareness. Coaching as a professional development strategy invites teachers to be coherent with what they think, feel, and finally do. Coaching also provides the perfect environment for teachers to explore the integrity of human beings with their students (Martínez Cardona & Pulgarín Taborda, 2016).

In line with this finding, it could be argued that the development of professional skills, one of the main goals of any professional development program, depends primarily on the recognition of the importance of tackling personal issues first, and in this case, coaching could be a very appropriate strategy to be implemented.

Echeverri-Sucerquia, Arias, and Gómez (2014) found that “teacher development experiences should not only strive for the development of theoretical clarity but also for the development of critical awareness of the self and the world around” (p. 167). We think that if professional development programs include coaching as one of the strategies in their agenda, teachers will become better human beings and will raise their awareness about themselves and their surroundings.

Teacher professional development programs should also consider different aspects when designing and implementing professional development programs with coaching as one of the strategies and their professional development agenda. Goldvarg and Perel de Goldvarg (2012) remark that “trust is essential in a coaching relationship” (p. 48) and the coach must leave judgment apart and see the coachee as a whole and complete person. Cubeiro (2011) states coachees should find someone with whom they feel comfortable to talk about their concerns, someone with whom they can find improvement opportunities. Miedaner (2002) points out that when a person is looking for a coach, he or she should consider someone who has taken the coaching courses to make sure the person knows “the bases of the discipline” (p. 332).

Interdisciplinary teams should also be considered when having coaching as a strategy for professional development in teacher professional development programs. Baltar De Andrade, Carrasco Aguilar, Jensen Bofill, Villegas Fernández, and Tapia Rojas (2012) consider that teachers and psychologists contribute the best of their professional jobs when their relationship has been built with liberty and autonomy. In our study, teachers and psychologists decided to work together; it was not an administrative decision. Baltar De Andrade et al. (2012) also point out that both teachers and psychologists complement each other and learn together: teachers with their practical role and psychologists with their reflective one. In our study, the psychologists’ contributions were relevant after the second session when coachees started talking about personal issues that had to be addressed therapeutically.

Coaching sessions should be performed in an environment of trust and genuine interests (Goldvarg & Perel de Goldvarg, 2012). O’Connor and Lages (2005) remark that trust is crucial in a coaching relationship. Professional development leaders should also be aware of what Whitmore (2009) says: “Coaching is not merely a technique to be wheeled out and rigidly applied in certain prescribed circumstances. It is a way of managing, a way of treating people, a way of thinking, a way of being” (p. 19).

Suggestions for Further Research

Coaching can provide not only adjunct foreign language instructors at the university level with the opportunity to gain consciousness about themselves and their surroundings to become agents of change, but also primary and secondary teachers. We suggest further research on primary and secondary settings since coaching could provide many gains for all type of teachers at any level of occupational education to explore themselves, their beliefs, and their dispositions to change.

This research was an enriching experience since we had the opportunity to share knowledge and work from two different perspectives: foreign language education and psychology. We strongly recommend continuing to do research on coaching carried out by professionals of different areas that are involved in education, psychology, or any other human science.

We encourage scholars interested in the professional development research line to explore teacher professional development not only from the pedagogical and cognitive perspectives, but also taking into account teachers’ working conditions as stated by Imbernón (2011). Professional development goes beyond pedagogical aspects; it even goes beyond teachers’ personal issues because professional development includes teachers’ pedagogical development, knowledge about themselves, cognitive and theoretical development in addition to their working conditions that allow or avoid the development of their careers (Imbernón, 2011).