Introduction

Nowadays students are normally regarded as digital natives dealing with technological advancements easily and effectively. Nonetheless, some specific tools and strategies regarding information and communications technologies (ICTs) and digital media should be targeted in class to contribute to improving students’ digital competence. In the English as a foreign language (EFL) classroom, these ICTs and digital genres can be exploited to develop students’ communication skills, too. Yet, it appears that they are not being dealt with enough in many educational contexts, and students are required to learn about the conventions of other already old-fashioned or not so useful genres.

This paper hopes to address this gap by introducing a teaching proposal that revolves around the travel blog as one of the potential digital genres students may be familiar with and learn from. Particularly, it is advocated that teachers should follow a genre-based analysis to raise awareness about a particular genre before working on it with the students in the EFL classroom. Even when the travel blog has been chosen as the cornerstone for this proposal, the process illustrated here can be replicated to examine and understand any other genre wanted. Actually, this is favourable not only for teachers, since better tasks can be designed and more help can be provided, but more importantly for students, who can develop their communicative and digital competences and have a more meaningful learning experience.

Moreover, learners should get as prepared as possible for the globalised 21st century that we live in, and that involves acquiring certain competences, including the 4Cs of 21 st -century learning: critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity (Partnership for 21st-Century Skills [P21], 2017). Besides fostering the learning of English, the travel blog can be perfectly employed to help students enhance those competences, as the teaching proposal will try to show. Learners can develop their management of ICTs while they critically realise that the Internet is a medium with which to communicate in English with an international audience or to collaborate with people from across the world.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. First, the theoretical background on which the proposal rests is described, explaining the advantages of working with (travel) blogs in the English class, and including communicative language teaching (CLT), task-based learning (TBL) and the writing-as-a-process approach. Next, the proposal will be described, analysed, and justified in the light of the theoretical principles discussed, and samples of the activities and tasks designed will be presented. Finally, some conclusions will be drawn on how this intends to foster innovation in the EFL secondary education classroom highlighting its main strengths.

Theoretical Framework

Educational Benefits of Working With Blogs in the EFL Classroom

(Travel) blogs constitute a source of authentic materials influencing the modes and uses of current communication, inviting interaction among English native and non-native speakers. Introducing blogs written in English by “international speakers” in class may expose students to authentic contexts involving varied cultures and values. This will make them aware of English being used as a vehicle for global communication-with an international status as a lingua franca (ELF) (Baker, 2015; Jenkins, 2007; Mauranen, 2012; Seidlhofer, 2011). This is especially relevant, as achieving successful communication in international encounters with other bloggers and users where English is functionally used is advantageous for students’ communicative competence in English. By interacting with similar or other kinds of English speakers, learners participate in interesting group discussions while being able to express individual preferences and tastes. Overall, this computer-mediated scenario assists them in building a greater sense of autonomy and empowerment (Yang, 2009).

Regarding the promotion of learners’ digital competence, Pérez-Tornero (2004) pinpoints four main uses students should control in the digital sphere, which can be dealt with when introducing (travel) blogs in the EFL classroom: (a) operative, when students learn to exploit the maximal possibilities of something in the web, in this case, the travel blog (for instance, reading for specific or general information); (b) semiotic, when they interpret different codes mixing language, image, video, or sound, and understand how these may complement the textual information in a blog; (c) civic, by effecting a responsible and self-critical use, being aware of the pragmatic and ethical aspects of publishing online, and accepting accountability for their performance; and (d) cultural, as they need to show respect and open-mindedness towards different cultural practices and points of view within the virtual discourse community of the blogosphere. By working on this genre, students’ digital competence can be overall enhanced.

Furthermore, blogs can be fruitful to propose innovative EFL methodologies. Learners should become protagonists of their learning by exploring, making hypotheses, and drawing conclusions regarding language and content as they go along. (Travel) blogs can likely match their interests and personal experiences, both in their current context and for the future. Many students are reluctant to start writing on a blank page, far more in English, so to fight this, they will be offered through blogs a clear context and a purpose clarifying what their written outcome should be like-be it a comment or a post. In so doing, students can work on synthesis processes due to the timely and spatial characteristics of the web where the blog is hosted, and for the creation of their texts and the subsequent publication, a whole array of previous or further projects or tasks can be created (Rojas Álvarez, 2011), as will be shown in this paper.

Blogs also present a motivational role in the classroom for being applicable to real-life situations. Students may be really willing to use them, especially since not many digital genres tend to be included in the EFL classroom in some educational contexts (Pascual, 2017). Students may want to set up blogs and give them shape and accept publishing new content periodically. Writing comments or posting for an authentic potentially global audience is considered not only to boost students’ motivation and participation when learning English, but also to promote their analytical and critical thinking (Murray & Hourigan, 2008). This helps them to show their progressive achievements and increase their sense of self-efficacy (Azmi, 2017).

In that respect, a genre like the blog enables students to learn by doing and to practise the macro- and micro-skills of reading and writing. As for the latter, both individual and collaborative writing can be worked on thanks to blogs, and the fact that students’ texts are to be eventually published creates a certain degree of commitment, carefulness, and revision. Engaging students to sense that pressure has positive effects at other levels, including content quality, organizational skills, and grammar use (Hegelheimer & Lee, 2012).

Communicative Language Teaching and Task-Based Learning

The main principles of CLT underpin “an approach to language teaching methodology that emphasizes authenticity, interaction, student-centered learning, task-based activities, and communication for the real world, [with] meaningful purposes” (Brown, 2007, p. 378). These many advantages can be profited to prepare students for a future where the English language (and digital genres/media) is playing a crucial role. Wesche and Skehan (2002) also highlight, among other CLT principles, learner interaction, contextual links to the world, and room for creativity from learners’ profiles.

As the EFL classroom is moving away from a traditional method to adopt a more active approach, inherent changes both in teachers’ and students’ roles need to be brought about. Currently, teachers are not supposed to be models correcting mistakes and ensuring flawless oral and written discourse (Richards, 2006), but to perform as learning strategy coaches and guides (facilitators and monitors). This implies encouraging students to perceive errors as natural, helping them in their specific needs for language learning, and providing them with the tools, skills, and assistance, in this case to discover a new digital genre. On their part, learners should take a higher degree of responsibility for their own learning and will be driven towards cooperative rather than individualistic tasks often incorporating pair/group work. Collaborative learning and interaction skills should be promoted as successful ways of developing students’ communicative competence and learning by doing-trying out and making mistakes.

Task-based approaches (Ellis, 2003; Willis & Willis, 2007) place the primary focus on meaning and entail a gap (information, reasoning, etc.) for students to fill. So, they should share ideas in different groupings, solving challenging problems, or facing real-life situations (Center for Teaching Excellence [CTE], 2017). To complete these tasks, students will go through different cognitive processes: low-order ones-selecting, classifying, ordering-or high-order ones, like creating or synthesizing (Bloom, 1956). Different thinking routines and challenging tasks revolving around travel blogs will be designed to apply TBL to the genre and lead students to work more collaboratively and autonomously.

The Writing Skill: A Process-Oriented Approach

Given the nature of the travel blog, the core focus will be placed on written-based skills: reading and writing. A beneficial and innovative approach to combine both and greatly develop students’ writing is the process-oriented approach, where the process of going through the completion of a text is overtly emphasized over the value of the final product (Hedge, 2005; Kroll, 2001; Sokolik, 2002; Tribble, 1996). This approach drives learners to write (either printed or digital genres) in a realistic way, acquiring skills to do so with specific purposes and audiences. If learners are conscious of the stages to produce a text and exercise them in class, they can become more critical writers. Thus, learners should realize that writing is a tough but necessary road that needs reflection and effort, but that if they tackle those, they can develop their self-efficacy.

The first stage in this process is generating ideas. Encouraging brainstorming and gathering information will assist students in overcoming potential motivational problems towards writing or “imaginative blocks” (Tribble, 1996, p. 107). Enough time should be devoted to this stage, understanding that self-evident ideas and clichés appear earlier than more complex and original ones (Sokolik, 2002). Second, some focusing tasks help learners select the most outstanding ideas from that brainstorming, and narrow the scope of their writing (Hedge, 2005). Third, the organisation of those key aspects takes place, and students frame their ideas through activities to start structuring their messages effectively. Once students begin to draft, they should pay attention to textual development and structure over accuracy of linguistic aspects (Sokolik, 2002). This is even more relevant in informal digital genres like the travel blog, characterised by a high degree of flexibility regarding these aspects.

Before the final draft turns into the final product to be evaluated, a revising and editing stage allows learners to check whether the writing task has been successfully completed. They can revise the content, structure, and pragmatic use of the language in their output, and may then seek for specific mistakes involving spelling, grammar, or punctuation. These revisions can be tackled via peer-assessment and evaluative tools, such as checklists or rubrics, for one group of students to comment constructively on other groups’ output. Indeed, Kroll (2001) recommends that “the evaluation criteria should be identified [before] so that students will know in advance how their output will be judged” (p. 226). That way, they can be more confident about what to emphasise or revise, and consider the appropriateness of their discourse for the potential audience.

In the following section, the process followed to get to know in depth the genre of the travel blog is outlined, with an explanation of the results obtained from the generic and linguistic analysis.

The Teaching Proposal: Blog in!

Steps Taken in the Design of the Proposal

To design this teaching proposal on travel blogs, first a representative corpus was compiled to highlight their most important generic and discursive features concerning structure, lexis, grammar, orthotypography, or pragmatics. This analysis enabled me to gain a better understanding of the (sub) genre of the post, and its register and relationship with the comment and the potential responses to the comment, as well as to have a database to design activities and tasks for future implementation in the EFL classroom.

The (travel) blog can be reckoned to be a genre, as it is “a class of communicative events, the members of which share some set of communicative purposes” (Swales, 1990, p. 58). This notion has changed alongside time and, from a fixed entity with some purposes and constraints, a genre is viewed now as quite a flexible dynamic entity that shapes itself according to its audience and impact (Bhatia, 2004; Swales, 2004). This is especially the case with digital genres that tend to change, adjust to the users’ needs, and adapt to new contexts.

In relation to that, travel blogs aim to reach a heterogeneous audience interested in discovering new places and learning first-hand anecdotes and curiosities about them. So, the communicative purpose of the travel post is to offer a description of a place, along with the atmosphere or the experiences that someone has encountered for others to relive and adapt these trips, or enjoy themselves by reading about issues of their interest. The members participating in the travel blog through the different genres (posts, comments, replies to comments) implicitly contribute to its dynamicity and dialogicity.

As for the generic relations affecting the travel blog, the post and the comment form a genre chain, since there is a key sequential dependence with “chronological ordering, especially when one genre is a necessary antecedent for another” (Swales, 2004, p. 18). This way, bloggers frequently address the readership along their posts, and readers tend to give feedback and express their emotions by commenting on posts they have read. This bidirectional and conversational discourse allows for a fairly informal and oral-like style when interacting in the blogosphere. All these elements have been borne in mind to design the teaching proposal, so that students can understand the communicative purposes of the different genres and the relationships among them, and effectively employ them to communicate beyond the EFL classroom.

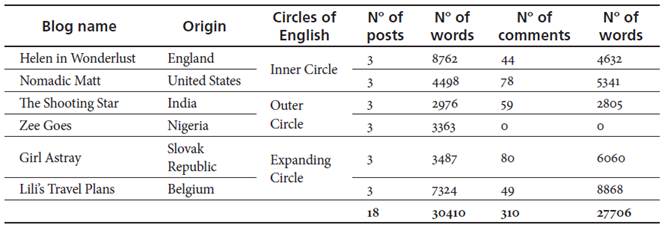

For the compilation of the mentioned corpus, six travel blogs were selected from a sample of online international bloggers belonging to different linguacultural backgrounds. I considered Kachru’s circles (Bolton & Kachru, 2006; Crystal, 2003) when selecting this sample to proportionally incorporate blogs by English natives (inner circle), by people who do not speak English as their L1 but frequently use it in their countries for official or institutional purposes (outer circle), and by English non-native speakers who use English as a foreign language (expanding circle). These texts could be representative and could be analysed, first, and used in class, next, to work on the role of English as a vehicular tool for global communication (ELF).

Three entries from each of those blogs were chosen, making up a small-scale corpus of a total of 18 entries (30,410 words, see Table 1). Each entry comprises the post written by the author of the blog; the comments made on it within the range of one year; and the author’s response to them, to obtain a precise panorama of their genre relations (Swales, 2004) as explained above. The corpus, despite its size limitations, captures and represents the tendencies of the practices travel bloggers and readers follow individually and share as members of the same global virtual community.

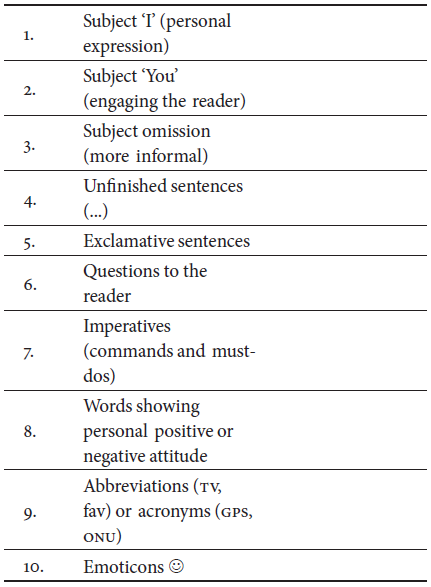

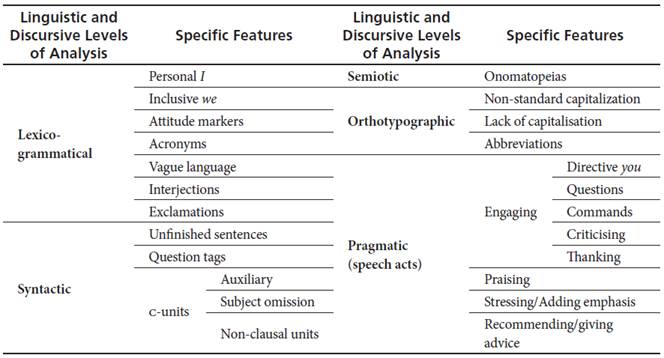

Once the corpus was compiled and the genre understood, travel blog posts and comments were manually analysed in terms of their main lexico-grammatical, discursive, and pragmatic features. Thus, the following step was to create a taxonomy (see Table 2). This was aimed to be the basis for the teaching proposal, together with CLT and TBL principles. Hence, tasks and activities were designed to guide students to the creation of an original comment and post, after raising awareness of the two genres and the participation of bloggers from different backgrounds.

Table 2 Data-Driven Taxonomy Including the Most Prominent Linguistics and Discursive Features in the Corpus

Differences were traced as to the frequency and use of these features in travel blog posts as opposed to comments.1 This may stem from two reasons: first, the communicative purposes of each sub-genre invite certain features to recur more than others-for example, recommending sentences usually abound in posts, while praising or criticizing sentences rather fit in comments. Second, the users’ language level of proficiency depends on their background concerning English and is reflected in the (non) existence of certain features that imply a higher degree of language deployment (acronyms, onomatopoeias, or abbreviations). From the beginning, these findings were considered for the design of the teaching proposal.

Finally, the content of the travel posts was also analysed, and some repeated patterns or stages discerned. These are the “moves” of a text or a genre (Swales, 1990, 2004). Based on the observations from the corpus, it is recurrent to include a situational move setting the post spatio-temporally, plus a descriptive move offering anecdotes about the trip. Then, the post presents some closure with conclusions, and an invitation move introducing the sub-genre of the comment. This structure, widespread among the virtual community using travel blogs, should serve to teach students how to compose their own travel posts and comments.

Critical Analysis and Strengths of the Proposal

In this section, the teaching proposal will be analysed and commented on, paying attention to the principles introduced in the Theoretical Framework and displaying some sample materials and resources to show students’ ideal process from receptive skills to productive skills in the use of travel blogs. That way, how to improve learners’ communicative and digital competences will be illustrated.

Blog in! is based on authentic materials, published in actual travel blogs, to offer students a source of meaningful input, with authentic rich contexts and real purposes for communication (Brandl, 2008). It is also a potential model for learners’ own production of posts and comments in an ELF context of communication. The lessons aim to make students aware that they are not supposed to reach a native-like level, but to use the L2 in an intelligible way. Instead of deficit communicators constantly making mistakes, they are active language users with a potentially similar audience to them (Baker, 2015). So, different tasks and activities in the lesson plans are intended to promote communication, push students to employ the language actively, and guide them through the writing process until the intended outcomes are reached-writing and publishing, first of a travel blog comment and, ultimately, of an original post.

Process-Oriented Writing

To start generating ideas (Hedge, 2005; Sokolik, 2002), students’ schemata and previous knowledge about the topics of travelling and blogs are raised with tasks including guiding questions and the brainstorming technique. Students can start discussing the travel blog and its communicative purpose and contrast this digital genre with other typical ones used on the net (e.g., a FAQ page, a forum, a Wikipedia entry, or a downloadable brochure). This way, students begin to raise awareness, and teachers may find students’ starting point so as to cater for different learning profiles/rhythms.

In the second stage-focusing ideas-, learners are offered tools and materials to organise their hypotheses and ideas, and decide which ones of these are worth considering for the draft of the travel blog post or comment. At this point, key 21st-century skills like critical thinking and creativity (P21, 2017) are promoted in search of the selection of the best ideas and structure for their texts. To do so, students are asked to examine a model post of their choice and identify the salient parts of that text and their distinguishing functions-leading them to unconsciously connect it with the researched move structure of the travel blog post.

For the learners’ draft of their initial versions Google Docs is employed. This collaborative tool is fruitful as it allows students to work in pairs or groups simultaneously, despite not sharing physical space (easily adding, modifying, and organizing ideas). The teacher can check individual work, keep track of the progressive versions, and give personal/ specific feedback to students.

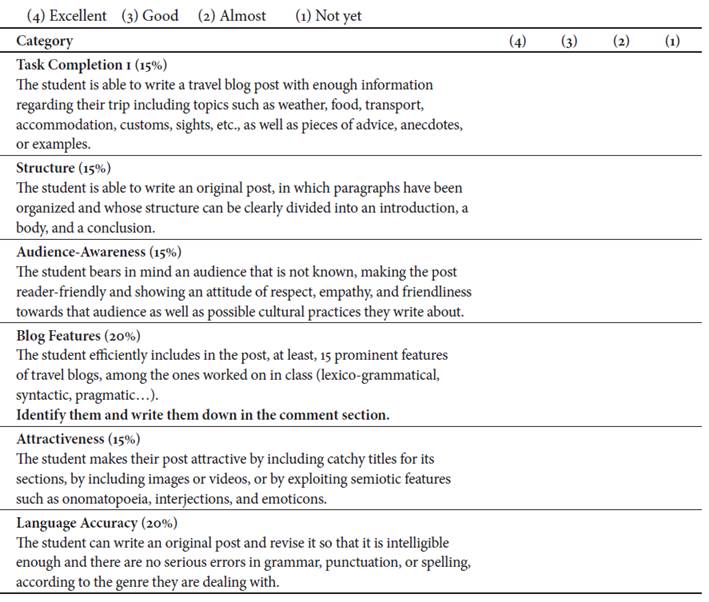

Finally, steps of revision and edition of their texts are encouraged mainly by the use of a two-fold checklist (see Appendix), with which learners-and teachers-can evaluate their process and final product. Firstly, students can look at it when writing the comment and the post to carry out these tasks successfully and evaluate their proper performance and process (as a guide to meet their expectations and the teacher’s). Secondly, students are also expected to evaluate their partners’ comments and posts and give them feedback, helping each other to develop more meaningful learning. In their checklists, students should mark from 1) Not yet to 4) Excellent different evaluation criteria about content (meaning), structure (moves followed), appropriate language use (pragmatically speaking); and linguistic choices (blog features presented in Table 2).

Moreover, online revising and editing tools such as monolingual and bilingual dictionaries, thesaurus, spell and grammar checkers should also be used. That way, students will help each other to proofread and edit their work, ideally with the support of these tools and in an ongoing way through the process. However, assessment criteria will not focus so much on accuracy and error correction as on comprehensibility and content issues, for being considered of greater relevance, as mentioned before.

Evaluation

Before finishing Blog in!, some exit tickets will be employed to make students reflect and draw some final conclusions. These concern not only their learning, interest, and effort, but also the activities and teacher’s help. Instances of the questions they should respond to include completing statements or multiple choices (see Example 1). First, this may be useful for learners to critically underline strengths and weaknesses and to promote their autonomy and intrapersonal skills. Next, from this activity teachers can gather students’ information and feedback to introduce improvements. ICTs such as Padlet or Socrative or rather traditional handouts can be used as exit tickets. To collect feedback from both printed and digital sources, in the proposal Padlet is used for the comment exit ticket and a designed handout for the post one.

Example 1. Sample questions of the printed exit ticket after writing the post.

Three things I learnt about blogs…

1. ______________________________

2. ______________________________

3. ______________________________

My effort these days in class was:

Integrating Skills and Language Content

Although the final outcome of Blog in! is to produce some digital texts, macro-skills are integrated and language functions and features practiced to enable learners to accomplish the final task.

Students might need first to explore the topic of travelling, read information about trips, and share their experiences. Once interest and motivation have been generated, students should start going through the commented genre-based approach (Bhatia, 2004; Swales, 2004) to know what a blog is like, and which texts are written there. That way, they will be able to replicate them thinking of their potential audience and being communicatively efficient. If students see the advantages of using a (travel) blog, they can improve their language skills and learn about other cultures and values.

Therefore, learners move from a receptive use of the language, focusing on reading skills, towards a productive use by the completion of writing a comment and a post on a travel blog. First, students practice reading sub-skills such as skimming to understand the post’s general information, by answering questions such as What’s the author’s opinion about the food? or What was accommodation like? They continue by practising reading strategies such as inferring and guessing the meaning of words from context about recurrent travel blog topics (e.g., transport, sights, etc.). Moreover, activities focus on blog features and form, so that students can concentrate on the language content they are supposed to learn and produce. In Table 3, students can practise their scanning skills (Grabe, 2009) by identifying instances of different features of the genre contained in posts they have previously read.

Simultaneously, activities intend to promote learners’ oral skills and subsequent development of their interacting skills (e.g., negotiation of meaning, turn-taking, etc.). This should foster students’ communicative competence while increasing their learning opportunities and help them to take up the challenge of writing. As they are “doing”, and interacting, and trying to accomplish a task where they are the main focus of instruction, collaborative learning is also being enhanced (CTE, 2017) in different groupings.

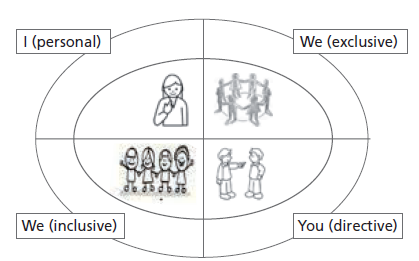

Figure 1 shows one of the many examples that combine the use of oral skills with the focus on language form. Students are expected to distinguish and employ the different uses of personal pronouns, as they are one of the salient features in travel blog posts and fulfill different purposes. In this adaptation from the “circle of viewpoints” (Harvard Graduate School of Education, 2018), learners take turns assuming the role of one pronoun each time and contributing to the group discussion from that perspective. Scaffolding and examples are also provided to guide the reflection on the functions of these lexico-grammatical features, as well as on their own travelling experiences. Later, they will see how and when to employ the different combinations of pronouns in their texts.

Engaging Students

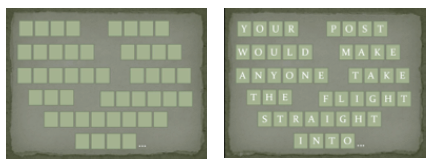

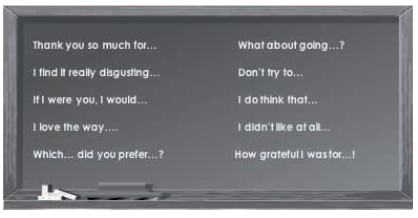

As some activities proposed may entail a deep conceptual or linguistic difficulty and cognitively-demanding participation from students, interactive tasks are interspersed throughout the lessons. Some of them bet on the gamifying part of learning to make it more appealing and motivating for the student. In the activity shown in Figure 2, students simulate the TV contest The Wheel of Fortune to work on speech acts recurrently traced in blog posts and comments. Learners are rewarded for their effective performance in the task with catchy idiomatic phrases to be used in their posts.

Furthermore, varied intelligences (Gardner, 1993) can be matched in the rationale of the travel blog, as students are prompted to interact with other people (interpersonal intelligence), find out about the environment and habitats of places (naturalistic intelligence), receive information from pictures or videos (visual intelligence), and discuss their thoughts and stories (linguistic intelligence). This inherent combination plus specifically-designed tasks can greatly cater both for diversity and differentiation in the EFL classroom, aiding students to become more proficient at their areas of strength and to improve some areas of struggle.

Differentiating Strategies and Activities

In connection with engaging students along the teaching proposal, learners needing differentiated instruction should be guided and helped. For them to reach the aims of writing a comment and a post, various strategies and resources are displayed. Input enhancement (Nassaji & Fotos, 2010) is included in students’ handouts as a strategy for the ones struggling through the tasks. This implies using different fonts and sizes and striking formats (bold, italics) to highlight relevant information in the headings and task explanations. Another way to deal with students’ potential blocks or worries, depending on their learning profiles and rhythms, is scaffolding (see Figure 3). By offering them structures to start their messages, they learn new linguistics items which they may adapt or complicate if they are high achievers, and which may make them feel more comfortable if they are low achievers.

Moreover, colour codes, greatly connected with students’ visual intelligence, are reckoned to be effective in that learners may find common points within the task to reach meaningful solutions. For example, in a form-focused activity one colour can be associated with each category of features under practice (subject omission, emoticons, exclamative sentences, discourse markers, etc.). Students should deal with a type of communication beyond the paper-based one-characterised by more flexible informal oral features-, so this visual support can be helpful. Likewise, cheat sheets-aiding materials hinting at possible answers, exemplifying concepts and easing the completion of tasks through scaffolding-are employed to support students and solve some of their concerns and problems, also bearing in mind diversity in class. They can be made with hints, partial solutions, or fully worked-out solutions to the activities proposed.

Added to those differentiation strategies, learners can reach the expected goals through a multiplicity of answers at many points in the lessons. They can choose the post they would like to read among a wide array of possibilities from the corpus; or decide which comprehension questions on the post they prefer to answer, as long as they reach a minimum to ensure the targeted practice of specific reading micro-skills. So, the idea that students need to be given responsibility and decision-making power is very much underlined for being beneficial in their learning process. Teachers should assist students in finding the most advantageous situation for them in this learning process.

This emphasis on differentiation and negotiation also derives from my awareness, as a teacher, that working with authentic materials and at this level implies high linguistic demand. Therefore, students often have a voice in their learning about what to do and how to do it. All these differentiated techniques seek to slightly adjust the conceptual level of the tasks and help students develop their self-efficacy and sense of comfort and safety, creating a low-affective filter (Krashen, 1982), which in turn brings positive effects to their learning.

Making Learning Visible

Thinking routines in the form of charts let students gradually structure the input they receive and summarise the main information in the output they produce. For example, in one activity students are asked to fill three columns: What I expect before actually reading the post, What I read! to confirm or refute their guesses, and What I think now! to go beyond and raise implications about both the content of the post, the author’s stance, and the form of the blog.

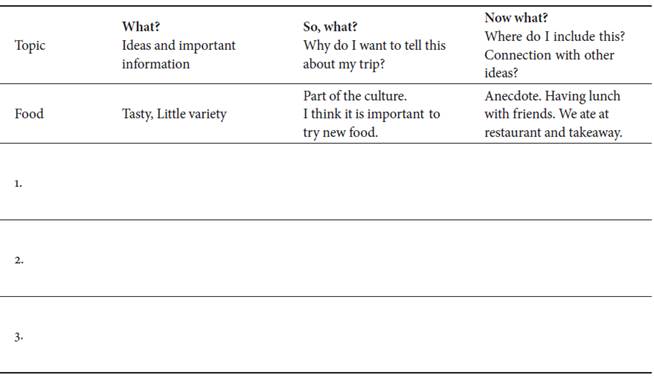

The exit tickets employed at the end of the sessions also contribute to making students’ learning more noticeable (see Example 1) and invite further questioning and reflection. Apart from that, when students are focusing and structuring their ideas, they count on some organisers (see Table 4) that help them test their ideas and place them in order, therefore rendering their learning visible (Clark, 2009).

Promoting Curricular Competences

The design of the teaching proposal clearly has competence-based goals and points at the learning of other cross-curricular values by introducing a digital genre in the secondary education EFL classroom. As working with travel blogs contribute to improving students’ reading and writing skills, the communicative and digital competences turn out as the most necessary ones. Within the former, grammatical, discursive, and pragmatic elements are worked on, whereas the latter highlights skills to successfully employ ICTs and digital genres.

A process-oriented writing approach will support a better learning to learn competence for students, who will become more conscious, responsible, and autonomous in using the language in different learning situations. The use of checklists and exit tickets, as previously shown, is also beneficial to foster this competence. Moreover, devoting time to other values like critical thinking, creativity, and entrepreneurship in the secondary education EFL classroom can also contribute to it.

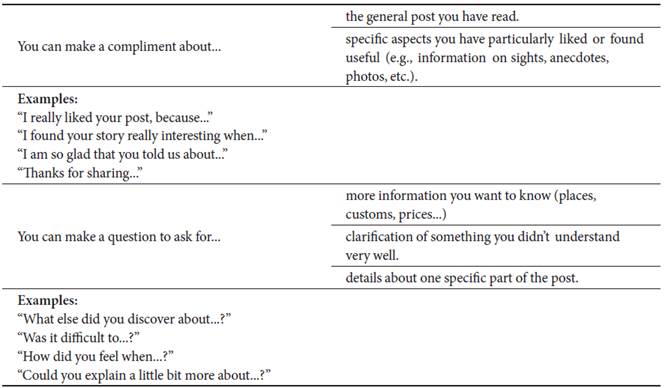

The pragmatic competence is also worked throughout the lessons planned, as (travel) blogs enable students to meet real language users from the worldwide virtual discourse community. To be pragmatically efficient, students are led to get practice in addressing a likely unknown audience in polite ways, not being disrespectful or particularly assertive, and showing a positive face (Brown & Levinson, 1987). So, the social and civic competence is reinforced through the lessons to promote a more critical thinking and well-behaved manners when expressing their ideas. To do so, structures via scaffolding and activities are practised to be appropriate and demonstrate friendliness. In Table 5, students learn to make a compliment through different expressions fulfilling the functions of thanking or praising, as part of a writing task.

Linked to pragmatics, using travel blogs can promote students’ further-reaching intercultural awareness competence, as engaging in online conversations may imply connecting with people from distinct backgrounds or talking about totally different places (e.g., Sri Lanka in Helen in Wonderlust or China in Lili’s Travel Plans). The teaching proposal raises expectations for students to show open-mindedness and empathy when reading and writing about other people’s beliefs, customs, and cultural practices (religion, food, music). These aspects are promoted similarly to the pragmatic ones and have their weight in the checklist for evaluation (see Appendix).

Moreover, the checklist is a beneficial resource to encourage students’ development of the learning to learn competence, as self- and peer-assessment enable them to gradually become more autonomous and critical in creating and evaluating their output and others’. They can bear this process in mind when using travel blogs beyond the lessons to continue learning to read and write them.

Conclusion

In the 21st-century EFL classroom, the new modes of global communication brought about by the technological advances of the Internet and the role of ELF need to be explored. Digital genres have gained a fundamental role in this respect, blurring time and space constraints and widening the audience. Students can and should enhance their digital literacy and competence in the EFL classroom. In this context, a teaching proposal around the travel blog has been offered to promote learners’ communicative and digital competences.

Blog in! is aimed to be implemented in an EFL secondary education classroom of 13-14 year-old learners in the span of about two/three weeks, and intermingles teaching methodologies (genre theory together with CLT and TBL), approaches (writing-as-a-process), and concrete techniques (to promote gamification, attention to diversity, visible thinking and learning) to offer an innovative exploitation of a digital genre. This combination serves to link the whole process of reflection, analysis, design, and potential implementation that teachers should ideally go through when introducing specific text types in the classroom. This paper has attempted to show the many benefits for students that can be achieved when teachers previously explore the genre they like to deal with in class and bet on more genre-informed writing instruction.

On the one hand, allowing students to work following CLT and TBL approaches, and fostering collaborative learning in which students have to make decisions and solve actual problems along the process may set off benefits for them. They need to make choices through the learning process and are expected to work with different group patterns to foster meaningful knowledge. In this proposal, the teacher ideally is just a support for students not to get lost. In the end, they should be aided to be more autonomous in the process of learning a foreign language.

On the other hand, gaining insights into the function, structure, and discourse of a digital genre enables students to better comprehend what they read and be conscious of what they are expected to ultimately produce. (Travel) blogs are sites of informal, dialogical, and immediate communication students may encounter in their future, and can be highly relevant for students, since blogs invite them to face real opportunities for computer-mediated communication with native and non-native English speakers alike.

The type of interaction in travel blogs is different from other genres, as drawn from the discursive and linguistic analysis, and should make students raise awareness of the increasing role of global computer-mediated interaction and communication. They are constantly searching for information on the Internet, and they are or will be virtual users of a digital genre like this, so learners must become more critical and responsible when using ICTs or digital genres at the same time that they become more proficient in their language skills in English.

Moreover, travel blogs can be employed to work on both key competences and cross-curricular aspects, involving cultural and social values, as exemplified in the analysis of the teaching proposal. Students’ communicative competence may improve further by engaging in the real encounters within the blogosphere and producing the typical discourse in this medium. This functional use of students’ L2 has implied in this case using an informal and dialogical register and specific lexico-grammatical and pragmatic features practised throughout the lessons. Simultaneously, students are expected to encounter and regard other cultural practices and non-linguistic codes with a more critical eye. To do so, tasks focus on accomplishing a greater degree of self-reflection and self-efficacy.

In brief, the procedure taken has led me to gain insights into the genre that allows me, then, to bring it into the classroom and exploit its characteristics focusing on the different skills and competences students are expected to develop and improve and contributing to a more integral learning. This teaching proposal has concentrated on the travel blog to do so, but further proposals on different (digital) genres can be designed following a similar procedure and similar principles.