Introduction

The Daily 5 (Boushey & Moser, 2014) is a literacy framework that fosters lifelong habits of reading and writing and provides the foundation for students to build stamina for independent work. According to Boushey and Moser (2014), the starting point took place when the researchers wanted to give a structure to the learning environment, developing a new form to plan how students should spend their time in class working independently. Then, they wanted to change the learning atmosphere and their roles as teachers by creating routines and systems that stimulate independent literacy behaviors, embedded to the point of becoming habits. Accordingly, they had to put trust in the conviction that students had the skills and desire to accept the challenge of making attentive choices during independent periods.

At one point, Boushey and Moser (2014) encountered a question from one teacher when they were studying The Daily 5 with an expert from New Zealand, Margaret Mooney. The teacher asked, “I have thirty students. What are my kids doing while I’m trying to teach this small group of children?” to which Mooney responded, “They’re reading, reading to each other, revisiting books, writing, and trying something new” (p. 23). From this discussion evolved the following five steps defined by Boushey and Moser which marked their investigation:

Read to Self; the best way to become a better reader is to practice each day, with books you choose, at your suitable reading level. It soon becomes a habit.

Read to Someone; reading to someone allows more time to practice strategies, which help you to work on oral fluency and expression, to check for understanding, to hear your own voice, and to share in the learning community.

Work on Writing; like reading, the best way to become a better writer is to practice writing each day.

Listen to Reading; we hear examples of good literature and fluent reading. We learn more words, thus expanding our vocabulary and becoming better readers.

Spelling/Word Work; correct spelling allows for more fluent writing, thus speeding up the ability to write and to get thinking down on paper. This is an essential foundation for writers. (pp. 11-12)

The Daily 5 has presented a complete literacy block for the reading and writing skills. However, this approach did not work with the speaking skill as it was envisioned and implemented in a native English-speaking environment. Learning to produce a foreign language orally is not an easy task due to several affective factors that may have a negative impact on the learning process (Brown, 2003). According to Thornbury (2009), the lack of oral fluency in L2 may trigger frustration and embarrassment in learners of a foreign language, inhibiting face-to-face interaction. In our study, the introduction of the sixth step (the Daily 6 hereafter) aimed to fit the Colombian context and therefore focused on fluent, effective oral communication within a communicative framework. This is how the Daily 6 was born with the purpose of giving response to a crying speaking need evinced in a private school in Bogotá, Colombia. To tackle the need, we decided to bring this novel approach to the English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching and learning environment by integrating it as a oral-oriented task that involved an information and communications technology (ICT) tool and autonomous work. The ultimate goal was to offer an enjoyable experience that combines reading, writing, and speaking while teaching students behaviors of independence and self-monitoring through motivational means. This is where the link between this study’s main goal and the objective of the Daily 5 meet.

Background and Previous Research

Oral fluency

Brown (2003) states that oral fluency is a productive sub-skill that focuses on content rather than form. Earlier accounts on fluency were based on Fillmore’s (1979) four-way concept. According to him, fluency is the ability to talk at length with few pauses. Secondly, fluency is the capacity of expressing messages in a coherent, reasoned, and “semantically dense” manner. Thirdly, a fluent speaker should know what to say in different contexts, and finally, a fluent speaker should make use of creativity and imagination in his or her speech. Other authors have expressed that there are abilities beyond smooth delivery of speech that are needed for a speaker to be fluent in a foreign language. Richards, Platt, and Weber (as cited in Brown, 2003) state that a fluent user is he or she who displays command of suprasegmental features or, that for a user of EFL to achieve fluent speech, he/she must rely on abilities such as: coherence, reasoned talking, continuity, creativity, and context-sensitivity (Fillmore & Brumfit as cited in Brown, 2003). We followed a more syncretic definition synthesized by Lennon (2000): Fluency is “the rapid, smooth, accurate, lucid and efficient translation of thought or communicative intention into language under temporal constraints of on-line processing” (p. 26).

Consequently, we concluded that one of fluency’s main characteristics is speed of production, called conversational speed or native-like speed. This validates the seven criteria (mean length of runs, silent pauses per minute, mean length of pauses, filled pauses per minute, disfluencies per minute, pace, and space) selected to assess students’ oral fluency before and after the implementation of the Daily 6.

An aspect that hinders oral fluency according to Thornbury (2009) makes a very strong claim on the difficulty most learners face when dealing with the speaking skill. Most learning methods prioritize speaking as a means to practice grammar rather than as a rightful skill. The closest speaking might come to being treated as a skill is when students work on pronunciation. Most students feel that no matter how well they know grammar and vocabulary, they are not prepared to engage in speaking, and Thornbury blames this mindset on the lack of practise with genuine speaking. In other words, this obstacle thwarts the normal process of developing oral structures.

Different approaches to foster oral fluency in EFL, such as Gutiérrez’s (2005), attempted to enhance communicative skills. Gutiérrez implemented interactive tasks with ninth graders at a school in Bogotá, Colombia. The findings suggested that establishing some stages-as in the Daily 6-such as exposure, interaction, feedback, and final oral production, created a motivating environment for students. Thus, the students’ effort was directed towards the improvement of their oral fluency. Gutiérrez’s work made room for group work (as in the Daily 6) to relieve the pressure entailed by teacher-student interaction. The combination of these factors resulted in low anxiety levels, which have previously been presented as one of the aims of the Daily 6. In the same vein, poster presentations were reported by Lane (2001) and Tanner and Chapman (2012) to have conditions that provided potential advantages to language learners; such advantages are lessening anxiety and creating a supportive environment. Moreover, Mir (2006) expanded the concept of written journals to recorded oral journals. These journals were meant to help learners gain self-confidence rather than grammatical accuracy. As a result, learners engaged in more enjoyable speaking tasks that enabled them to see the development of their skills and become more confident when speaking.

Similarly, Alam and Uddin (2013) developed a study that sought enhancement of oral communication skills of sixth graders at a public school in Pakistan. The study’s results showed that providing students with opportunities for practicing oral language and using teaching strategies combined with peer and self-correction, were key factors that fostered improvement in students’ oral communicative skills. The relationship between such a study and the present lies in the sub-skill in which both were focused, and on the fostering of learner autonomy. The latter is a major characteristic of the Daily 6 and was a great indicator of success in Alam and Uddin’s study. Other studies (Duque, 2014; Suarez Rodriguez, Mena Becerra, & Chaparro Escobar, 2015) attempted to determine the effect of self-assessment practices on young adults’ oral fluency and illustrated how collaborative learning raised participants’ awareness of their mastery of English.

Besides collaboration and self-assessment practices, interactional tasks have also been implemented to enhance oral fluency (Usma, 2015). Usma’s findings supported the idea that teachers should include more of these tasks into their teaching practice to develop skills related to oral fluency, connected speech, and the use of fillers. More recently, Montilla, Ospina, and Pineda (2016) designed an approach with similar results to the Daily 6; they confronted the negative anxiety experienced by adolescents when speaking in English. However, the tool used to lower anxiety was audio blogs recording, showing that new technologies in education to teach EFL leads to a change in the participants’ attitude towards learning activities. Accordingly, we chose VoiceThread™ as the tool to help the participants to speak fluently.

Blended Learning

The Daily 6 is a blended approach that exploited the appealing characteristics of ICT tools, the structure of the Daily 5, and the sixth step-Speaking to Someone-added to the former approach to foster speaking fluency. ICTs are becoming so pervasive that professionals in education must explore the changes they trigger in learning processes. Blended learning systems are defined by Graham (2004, p. 5) as “the combination of instruction from two historically separate models”. These models are (a) traditional, on-site, face-to-face (F2F) systems and (b) computer-based technologies. However, Sharma (2010) argues that this is “the classic definition” (p. 456) of blended learning and that the term continues to develop. Singh (2003), indeed, continues to develop the concept stating that its aim is to complement distance learning with F2F classes. Accordingly, Oliver and Trigwell (2005) have defined the term as a combination of a number of pedagogic approaches and any learning technology.

In addition, McDougald (2013) discusses the number of tasks that can be done in teaching when using ICT and the advantageous availability of authentic material as well as web-based material, which foster the development of real-world skills among learners. This is where VoiceThread™ comes to light in the present research. The Daily 6 is viable through VoiceThread™, for it is a web-based storytelling application designed to allow users to upload videos with audio, optionally accompanied by pictures or documents. This offers the student a smooth experience and the possibility to practice meaningfully once he or she has gathered enough data from the first five steps of the former approach-Daily 5.

Bailey (2005) provides insights on the use of technology for teaching speaking. We highlight the use of chat rooms, which, as explained by these authors, are web tools that allow interaction between users. Although these tools used to limit conversation to text typing, Web 2.0 tools comprise new technology that allows for voiced chats. Jepson (2005) studied the repair moves of L2 learners when engaging communication on voiced chat rooms. The results of his study showed that this Web 2.0 tool provides learners with opportunities to negotiate meaning, and functions as an appealing strategy for students to enrich and improve the efficiency of their communicative skills.

Blended learning has proved to be successful in certain other EFL learning processes, such as in Bañados’ (2006) study in an English program carried out with Chilean students. The results of his study demonstrate a “remarkable improvement in speaking skills” (p. 542). Bañados and his blended approach to English as an L2 for Chilean students (CALL programs, online monitoring, and on-site EFL teacher-led classes) demonstrated how quickly the learning of EFL and ICT have become of global importance, leading to the necessity of understanding factors that may affect the learning processes of young EFL students.

Need for the Study

A needs analysis performed on a group of 13 adolescent students at a private institution in Bogotá, Colombia, revealed affective and linguistic needs hindering students’ oral performance. The students participated in a diagnostic-achievement test that was video-recorded from three to four minutes. The recordings showed appropriate use of vocabulary to speak at a B1 level of the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR, Council of Europe, 2001), yet, their oral discourse mostly showed A2 features, as it was rather unintelligible and presented frequent hesitation. Although it is necessary for a learner to be knowledgeable of vocabulary and rules of the language, this is not sufficient to enhance learners’ speaking skill. Research suggests that EFL learners have limited opportunities to practice or use the language outside the classroom (Jaramillo Chérrez, 2007). Thus, the context in which students are immersed is a restraint to practice their oral English, diminishing the opportunities to become fluent speakers. In addition, nearly half of the participants in the diagnostic stage required prompting and support to maintain simple exchanges. The CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001) describes oral fluency from a global view, as the ability the speaker has “to make him/herself understood in very short utterances even though pauses, false starts and reformulation are very evident” (p. 29). Additionally, De Jong, Groenhout, Schoonen, and Hulstijn (2015) describe oral fluency “in terms of speedy and smooth delivery of speech without (filled) pauses, repetitions, and repairs” (p. 235). All of these criteria were not evidenced when assessing the students’ oral fluency.

Although some studies have been found in the field of oral fluency in oral production of EFL, there is no evidence that a study of the Daily 5 has been used as a springboard to design a methodology to promote speaking among EFL learners in Colombia. The Daily 5 was the subject of study for LaShomb (2011), who argued that the components “are all proven strategies to support children’s reading and writing development” (p. 5) by offering a strong base for a rooted system in routine and structure. In LaShomb’s study, the Daily 5-along with specific instruction-provided learners with “an efficient, cohesive, management system for implementing reading and writing instruction” (p. 5). The result was an unquestionably strong response in terms of attitude from the students. Even though the Daily 5 is a novelty in the Colombian English language teaching (ELT) context, it was created for American schools where speaking is not a concern as English is the learner’s first language. To fill in the gap, we modelled the format of the five steps proposed by its structure, so that students not only gain more responsibility in what they have to do during each one of the sessions, but also speak with some degree of fluency.

Accordingly, this research aimed to determine the possible effect that the implementation of the Daily 6 might have on the oral fluency of eighth graders at a private bilingual school in Bogotá, and the corresponding research question is how does using the Daily 6 (a modification of the Daily 5) affect the oral fluency of students with A2 (CEFR) English?

Method

The study was based on qualitative action research. This type of educative research focuses on teaching and learning issues that could be improved, and whose improvement would benefit a certain population and their social situation by developing new ideas and alternatives (Burns, 2010). This study was conducted with a group of students whose evidenced difficulty was a high or appropriate level of oral fluency, a goal not yet attained. Data were gathered after running an open, selective, and axial coding process for subsequent organization in a matrix that facilitated its interpretation. This eased the management of data and their subsequent analysis based on the grounded theory principles (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). We determined that recording students and counting the words and the pauses they uttered would be an effective way to assess their oral fluency level (understood as a result of continuous, natural, accurate, and effective speech). These observable temporal indicators of proceduralization were established as a major basis for oral fluency (De Jong & Perfetti, 2011; Towell, Hawkins, & Bazergui, 1996).

Participants

The population of this study consists of a group of 13 eighth graders, ages 13-14. They belong to upper-middle socioeconomic levels. The group’s oral language performance comprises an A1 English level (Council of Europe, 2001); however, the standards set by the school syllabus state that eighth graders should be competent at an A2 level (Council of Europe, 2001). Likewise, the group, when dealing with English, still works with lower order thinking skills such as recognizing and exemplifying (Krathwohl, 2002), which means that the Daily 6 represented a challenge for them, pushing them to synthesize old knowledge into pieces of oral discourse.

Data Collection Instruments

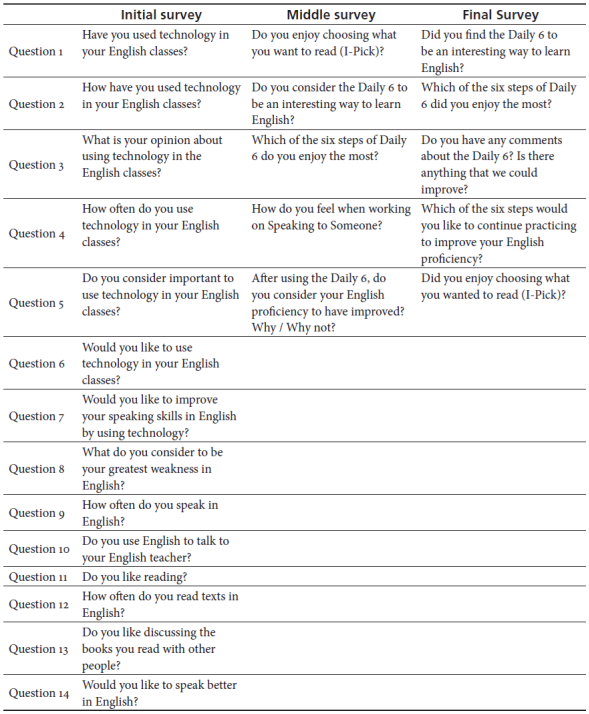

Data were collected through surveys, tests, a teacher’s journal, and video-recordings. Three surveys (see Appendix) were conducted to retrieve attitudinal data (Burns, 2010), students’ on-going perceptions, and final perceptions on the Daily 6. To determine the level of oral fluency, a pre- and a post-test allowed registering any gains.

Students’ oral interventions were video-recorded to measure fluency according to temporal indicators: mean length of runs, silent pauses per minute, mean length of pauses, filled pauses per minute, disfluencies per minute, pace, and space (Kormos & Dénes, 2004). Lastly, teachers-researchers used a weekly journal to report on factors such as motivation, oral fluency, anxiety, discipline, and cooperation.

For validity and reliability, we adhered to triangulation, peer-review, and piloting of the instruments as discussed in Johnson (1997) and Newman and Benz (1998). Likewise, researchers applied a trial of every single instrument in a classroom with similar conditions to the one implementing the Daily 6, testing a small-scale trial as described by Sapsford and Jupp (2006). In addition, interviews were aligned to the speaking section, part 1, of the international test formats KET/PET (University of Cambridge, 2010).

Procedure and Data Collection

The implementation of the Daily 6 comprised a total of 27 hours divided into three stages; each stage lasted seven hours and the students worked independently at home two hours per week. Three different lesson plans were created to guide each stage. The first stage was named “Foundation Lessons”. Foundation Lessons are meant to introduce students to the Daily 6 by creating and setting the rules for behaviors and the activities to be carried out. Stage 2 was named “Implementation Lessons”. These lessons were devoted to developing the 6 steps of the Daily 6 in short periods of time (3 to 9 minutes for each step). When arriving at the sixth step-Speaking to Someone-students should already be empowered with material, ideas, and information to start producing English orally through a voice recording posted on VoiceThread™. The implementation of VoiceThread™ sought to reduce the stress that speaking produces in students (Thornbury, 2009) by enabling them to choose the topic of their preference. Students spent longer on each step as they felt more confident and built-up more stamina for independent work. The implementation of the Daily 6 requires teachers and students to go over the six steps four times, increasing their pace periodically. The first lessons were devoted to becoming familiar with the procedure of the Daily 6. A useful strategy to achieve this was to have students fill a chart with the “most desirable” and “least desirable” behaviors expected during the lesson. Then, we focused on the students’ performance across the six steps; especially on the sixth step: Speak to Someone. This newly introduced step aimed at having students record their oral ideas through VoiceThread™ on a voluntarily selected topic such as comics, videogames, or sports. The easy access to this online tool allowed students to practice their speech outside the classroom in order for them to decide when their performance is satisfactory and ready to be shared with their peers. The final stage was essentially the same as the previous ones, however, they had to post their VoiceThread™, as in Stage 2, but this time they also had to leave voice comments on their friends’ posts. This stage came to an end with the Achievement Test.

The development of such test followed an interview format that elicited meaningful communication by means of information gaps. The students’ oral interventions were video-recorded for subsequent transcription. These video-recordings enabled us to evince the attitudinal traits displayed among students when taking the test at both diagnostic and achievement. Besides the attitudinal data retrieved, we measured fluency with temporal indicators after the transcription of the students’ responses. These two observable, temporal indicators of oral fluency can be used as indicators of proceduralization, a major source of improvements in oral fluency (De Jong & Perfetti, 2011; Towell, Hawkins, & Bazergui, 1996).

The classroom provided students with puff seats, books, a projector, speakers, and a computer so as to create a friendly and appealing learning environment. Every session was recorded for the teacher-researchers to retrieve attitudinal information on the behavior of learners regarding the resources provided, the instructions given, and the development of each of the steps of the Daily 6. Since the Daily 6 is intended to foster motivation and to build up stamina for independent work, the videos were used to look for signs (like body language, facial gestures, and readiness to start the lessons).

Data Analysis and Results

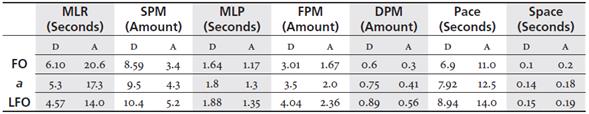

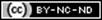

Students performed two oral interviews, which correspond to the diagnostic (D) and achievement (A) test. In Figure 1, the results show the average scores of the 13 students that were tested, and these averages are discriminated amongst the seven different criteria used to assess oral fluency: mean length of runs (MLR), silent pauses per minute (SPM), mean length of pauses (MLP), filled pauses per minute (FPM), disfluencies per minute (DPM), pace (P), and space (S).

The dot shows the exact average among each group of thirteen scores, and the lines above and under the dot represent the highest and lowest score of each group.

Figure 1 Comparison of the Diagnostic and Achievement Tests Results

The dot shows the exact average among each group of thirteen scores, and the lines above and under the dot represent the highest and lowest score of each group.

Figure 1 also shows the improvement reached by the participants with the upper line on each of the different criteria. The MLR, for instance, displays a huge improvement among the 13 participants, as opposed to S or the DPM in which amelioration was not as broad. Two other criteria in which participants demonstrated enhancement were the P and the SPM, which indicate less hesitation and more time filled within speech. Most of these temporal criteria comrpised undeniable evidence of progress in proceduralization (De Jong & Perfetti, 2011; Towell et al., 1996).

Table 1 shows the favorable outcomes (FO), the average (a), and the less favorable outcomes (LFO). These correspond to the seven different criteria and contrast the scores students obtained in both the diagnostic (D) and achievement (A) tests. The average scores show participants increased their scores in the MLR by more than 150%, and they also reduced their SPM by more than 50%. The other scores revealed less than 50% of improvement. The scores of the MLP clearly depict a slight improvement of 0.5; however, the overall results show that there were 50% less pauses per minute and these pauses were slightly shorter than the scores of the diagnostic test.

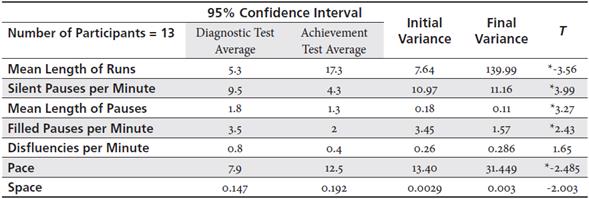

Likewise, to calculate whether there is a significant difference between the diagnostic and achievement test scores, a small sample hypothesis test for means was applied. Table 2 shows the scope of the implementation of the Daily 6 on students’ oral fluency in regard to the seven criteria aforementioned. The results of the hypothesis test indicated that five of the criteria (T = *) did not lie within the interval (-2.06; 2.06). Therefore, the participants’ performance on length of runs, silent pauses, length of pauses, filled pauses, and pace was affected significantly during the implementation of the present study. In contrast, the criteria disfluencies (T = 1.65) and space (T = -2.003) did not report gains as they did indeed lie within such interval.

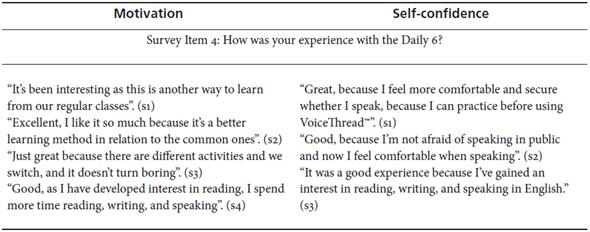

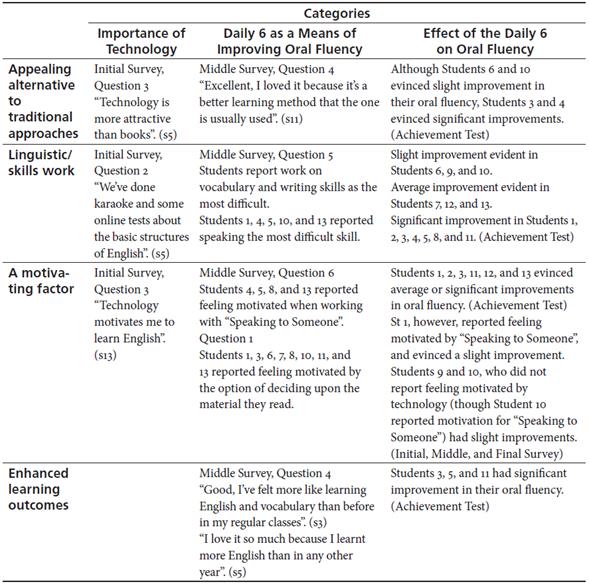

As to the qualitative data, in first place emerged affective factors such as self-confidence and motivation, which were crucial for the amelioration of oral fluency among students through their enhanced participation in the Daily 6. Although the ultimate goal of the study did not focus on affective factors, it was inevitable to witness evidence of self-confidence and motivation among the participants. Table 3 displays evidence retrieved from the surveys (see Appendix).

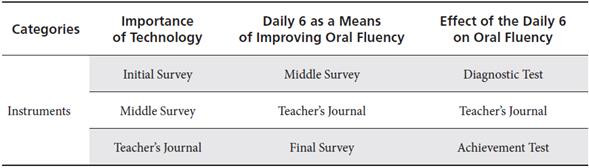

Subsequently, the qualitative data collected from various sources (see Table 4) resulted in three main categories: Importance of Technology for the Speaking Skill, Daily 6 as a Means of Improving Oral Fluency, and Effect of Daily 6 on Oral Fluency. These categories emerged after a continuous contrast of information and after following Creswell’s (2012) method of “generating and connecting categories by comparing incidents in the data to other incidents, incidents to categories, and categories to other categories” (p. 434).

Consequently, after a process of theoretical saturation-integration and the analysis of the interwoven themes and concepts, a core category emerged. Table 5 shows how different codes interrelate and are present among the three categories depicted.

Importance of Technology

As Table 5 shows, learners reported having used technology in their English lessons prior to the implementation of the Daily 6 in the initial survey. Technology was also a matter of importance present within the data retrieved among other instruments; the middle survey and the teacher’s journal revealed a positive impact of the sixth step (Speaking to Someone), given its relation to VoiceThread™. Although students struggled at first, they became familiar and accustomed to using this technology to enhance their oral fluency. In addition, students whose survey responses favored the use of technology, achieved significant improvements in the measurement of their oral fluency.

Daily 6 as a Means of Improving Oral fluency

Through instruments like the middle survey and the teacher’s journal, we gathered enough evidence to support the Daily 6 as an innovative and efficient approach to improve oral fluency. Some students even reported greater success in the current English lessons compared to other school years. After data triangulation, it was evinced that greater improvement came to those students with a positive attitude towards technology use and active class participation with the Daily 6. Moreover, as seen in Table 5, students who reported an increase in motivation to study English with the Daily 6 succeeded with superior scores in the achievement test for speaking.

Effect of the Daily 6 on Oral Fluency

The third and last category was basically distilled from the results of the diagnostic and achievement tests. A positive effect was predominant among learners’ oral fluency, while a minority of the participants experienced only slight improvements. The Daily 6 did not produce any negative impact on the participants’ oral fluency or learning process; there were no reports of unpleasant experiences. The absence of negative feedback from the participants and the scores led to a positive assembly of this category. Additionally, the achievement test and its video recordings gathered the evidence to state that the participants’ oral fluency had improved. Nevertheless, every learner achieved different degrees of improvement as previously evidenced in the achievement test scores.

Core Category

Undoubtedly, the core category for this study is “The Daily 6 as a Means of Improving Oral Fluency”. The data analysis process from coding stages, to category mapping and category integration, revealed a clear trait that led the population to identify the Daily 6 as an approach created to enhance their learning outcomes. It also led to identify the Daily 6 (category) as the widest sphere entailing literacy skills work, language skills work, the use of technology (category) in the English classroom, the perceptions and conclusions among the population as well as the evidenced (by means of the oral fluency measurements performed before and after implementing the Daily 6) and reported (by means of the Final Survey) enhancement of the population’s oral fluency (displayed in the effect on oral fluency category).

Conclusion and Discussion

The Daily 6 was implemented to determine the effect it might have on the participants’ oral fluency. The researchers found that the Daily 6 had a positive impact on the participants’ oral fluency thanks to (a) the decrease of anxiety, (b) the fostering of motivation and self-directed behaviors, and (c) the speaking opportunities provided by the Daily 6’s sixth step. These results answered the research question of this study by demonstrating that the Daily 6 positively affected the participants’ oral fluency. The effectiveness of the Daily 6 as an approach sheds light on the significance of this study’s results for the ELT community by adding a novel approach to the field. This statement also invites fellow researchers to deepen their understanding of the relationship between the lowering of enhancement of oral fluency with the Daily 6 and the assessment practices that should be implemented with this approach.

The effect of the Daily 6 on the participants’ oral fluency might be compared to the studies that have been published in recent years and in different places. The majority of these studies have reported enhancement of oral fluency; some of them have ameliorated affective factors such as anxiety to enhance oral fluency and some others have proposed repetition of tasks to make students aware of their own progress. There are two evident differences between those previous studies and the present one: population, and the approach with which oral fluency skills were developed. The latter is deemed more important and discussed in the following paragraphs.

Gutiérrez (2005) and Usma (2015) proposed interactional tasks among their participants to boost their oral fluency skills. Their studies share one similarity with the Daily 6 (and other studies hereby mentioned): decrease of anxiety among learners. It is safe to highlight that many studies have identified anxiety as an obstacle for would-be fluent speakers. Another clear example of such a study is Mir’s (2006). This article narrates how the author has implemented recorded oral journals in her lessons repeatedly, so her students would become accustomed to speaking English for several minutes, increasing their self-confidence and lowering their anxiety levels. The Daily 6 has achieved a decrease in anxiety levels among learners thanks to the itinerary nature of its six steps, rather than by just repeating the same task several times. Nevertheless, the recorded oral journals did not seek accuracy in grammatical terms but oral fluency of speech. The aforementioned article demonstrated that pushing the participants towards accuracy-oriented goals inherently increased their negative anxiety, instead of reducing it; this is a characteristic that is present in the Daily 6 as well.

Another key strategy used by some authors to develop oral fluency skills in their participants consisted of self-assessment and self-correction (Alam & Uddin, 2013; Duque, 2014). These authors intended to advise their participants with explicit knowledge on their progress. At mid-term, learners would start noticing a degree of enhancement that might encourage them by giving them a sense of accomplishment. The Daily 6 also provides learners with self-reflection opportunities but it does not entail any self-assessment stages. This means that the results of progress depend exclusively on the teacher’s assessment of the learners’ performance.

Moreover, a different implemented strategy was collaborative learning (Suarez Rodriguez et al., 2015). These authors argue that, in their study, collaborative work resulted in learners gaining awareness of their strengths and weaknesses and making plans to overcome such weaknesses. In a parallel way, collaborative work also promoted class participation among the learners, which in turn is evidenced by lowered anxiety. The Daily 6 entails collaboration in the steps Read to Someone, Listen to Someone, and Speaking to Someone. There are steps to be carried out individually, as well as steps that require collaborative work. In both, the present study and in Suarez Rodriguez et al.s’ study, collaborative work was reported as a cause for an observed decrease of anxiety among learners.

The most recent study related to oral fluency in Colombia (Montilla et al., 2016) also achieved low degrees of anxiety among its participants. However, the researchers applied a very specific strategy: audio blogs. According to the authors, audio blogs meant a novel opportunity for learners, who took advantage of this opportunity and became interested in recording their voices and participating in the blogs. This repeated task helped learners become aware of their own learning processes and changes in their oral fluency. The Daily 6’s sixth step “Speaking to Someone” was an equivalent of this study’s strategy. Students were prompted to record their voices using a web tool. The use of technology was welcomed by the participants of the Daily 6, and the recordings they made evidenced a slow but steady decrease in anxiety. These strategies led learners to experience positive changes in their oral fluency, which was ultimately displayed when learners were tested after the implementation of the Daily 6.

Although a sample of 13 students may not mean a major piece of evidence for the research world, teacher-researchers need to bear in mind that the Daily 6 entails an inventory of materials, resources, and strategies that required a high amount of data, preparation, and monitoring. To obtain a larger sample, the researchers would have needed a greater amount of records that might not have easy to control for transcription and qualitative analysis. This small sample may have helped us not only in the data collection process but also in the development of the different activities within a pleasant and low-anxiety environment. A group of participants comprising over 20 students would require more than 25 hours of implementation. Therefore, teachers implementing the Daily 6 need to bear in mind that it is mandatory to boast a wide variety of book materials for students to choose from. Should a classroom have more than 20 students, the teacher may face logistic issues implementing the Daily 6. In this light, it is necessary to take an inventory of the available resources in stock before starting the process. Consequently, an option could be to have a teacher-assistant while introducing the Daily 6, as once the methodology is introduced, the teacher-researcher’s role becomes that of an observer.

Lastly, this study is a call for pedagogical innovation towards current efforts to ameliorate the conditions under which oral production and communication are developed in the EFL classroom. It encourages researchers to bring a foreign approach to English teaching and learning (Daily 5), and then adapt it to become suitable upon its application in a local context with a specific need: the fostering of oral fluency in EFL. The results showed a positive effect on the participants’ oral fluency after implementing the Daily 6 using VoiceThread ™, displayed in the fostering of autonomous behaviors, development of higher order thinking skills through decision making and meaningful practice and interaction. The Daily 6 is a new approach that needs to and may be enhanced to become a well-known method to heighten speaking in foreign languages.