Introduction

The Constitution of Colombia recognizes the diversity of its territory in terms of cultures and languages; however, most of the policies created to guarantee a better quality of life for minorities (e.g., African-Colombian, indigenous, and Romany people) seem not to be put into practice. In the educational field, for example, indigenous students are expected to receive a type of education in which their cultural and language needs are considered; however, they are required to fulfil the same tasks as the mainstream scholars in the language of the majority of the population (not in their mother tongue), as on the national standardized test SABER. Due to that reality, indigenous students will be more vulnerable and subject to discrimination as the skills they have developed in school will be useless in their specific contexts.

Considering the previous information, we feel it is important to promote discussion between the majority and minority voices regarding education, interculturality, and bilingualism, and to share knowledge that fosters educational processes being carried out in the minorities’ distant contexts. Therefore, this document starts by presenting the theoretical framework based on the different educational and linguistic proposals surrounding indigenous and mainstream communities in Colombia through the aforementioned concepts. Later, it defines the methodological research design, and finally, it presents partial results of the study related to the analysis of data extracted from the information given by the participants.

Theoretical framework

Intercultural Bilingual Education (IBE)

Initially, the name of intercultural bilingual education (IBE) was given to an educational proposal designed by some South and Central American Ministries of Education to incorporate indigenous communities into the hegemonic educational policies, and into the national lifestyle by teaching them the dominant language and culture. Later, however, it became a way to legitimate and recognize the rights of the indigenous people, which had been denied for decades (Internacional de la Educación América Latina, 2011; López & Sichra, 2008). In this new approach, the cultural practices and mother tongue of the indigenous groups were promoted and taught along with the requirements of the national educational policies.

Different studies in South and Central America have made an approach to the goals and difficulties of IBE. For example, Hevia and Hirmas (2005) argue that even though cultural diversity is recognized in Chile, the indigenous groups are still regulated by the dominant culture which promotes the use of Spanish in the schools, denying the importance of native languages and the cultural practices of minorities. On the other hand, the “Modelo Educativo Bilingüe e Intercultural” (Ministerio de Educación de Guatemala, 2009) outlines the most important elements for developing an IBE school, such as legal aspects, teacher training, the educational system quality, and the parameters of interculturality and bilingualism, among others.

It is relevant to mention that within the Colombian context, the educational model for minorities (especially the indigenous population) is not called IBE but ethno-education; therefore, studies and investigations about it can be considered as following the principles of IBE. Particularly, the researcher and presidential adviser who has coordinated educational processes in ethnic groups (indigenous and afro Colombian), Luis Alberto Artunduaga (1997), for example, has worked towards the understanding of ethno-education as a way for indigenous peoples to enrich their educational model according to their cultural and linguistic needs; then, this proposal reflects a critical stance against minorities’ segregation and discrimination. Likewise, Castillo and Caicedo (2008) analyze how interculturality is understood by sectors such as the Ministry of Education, universities, and Afro Colombian groups to verify how appropriate this concept is in the ethno-education programs. Moreover, despite the fact that the IBE model tries to incorporate the minority groups by recognizing their language and practices, the reality shows another issue; therefore, when the model is critically analyzed there are many inconsistences in issues such as the subjects to be taught, the methodologies to be implemented in the indigenous school and the kind of tests which ignore specific knowledge obtained by experiences.

Due to the existence of 102 indigenous groups and 14 linguistic families (DANE, 2007; Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2013), and the previous claims related to the lack of protection of the cultural and language needs of these groups within the educational field in their territories, the central government has established life plans (planes de vida) to be implemented within the schools. These life plans are projects created by these groups to consolidate the perspectives for their future as a community and are brought to life through the “Proyectos Educativos Comunitarios, PECs” (Community Educational Projects, CEPs) that schools should have. This is how ethno-education-the name that IBE receives in Colombia-is put into practice; nevertheless, a dominant approach is still part of the educational system for minority groups, disregarding their unique lifestyle and authentic knowledge.

A Brief Overview on Bilingualism and its Application in Colombia

Along the teaching and learning of languages, the concept of bilingualism has been in the center of discussions as it deals not only with the field of education, but also with business, politics, marketing, and mass media, among others. Therefore, its definition has developed from establishing that a bilingual person is someone who has a native-like control of two languages (Hamers & Blanc as cited in Alarcón, 2002), to seeing bilinguals as those who can use properly two or more languages, and that can reflect their linguistic competences in the communicative process (Genesee & Nicoladis, 2006). These two broad ideas led us to think that the idea of bilingualism has evolved from being perceived only in a linguistic way, to a more complete concept that includes paralinguistic and cultural elements.

In Colombia, bilingualism has been linked to the teaching and learning of a foreign language, especially English, French, and German (Bonilla Carvajal & Tejada-Sánchez, 2016; de Mejía, 2006; Robayo Acuña, & Cárdenas, 2017). Currently, due to the tendencies of globalization, the English language has become the preferred language to use when communicating with people from other countries who do not speak the same language. This reason led the Colombian government to place special attention on English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching and learning processes, opening the opportunities for the creation of projects to develop and improve all educational levels (primary, secondary, university), framed within the 115 General Law of Education (Congreso de la República de Colombia, 1994). However, those initiatives haven’t been quite successful (Bonilla Carvajal & Tejada-Sánchez, 2016) and the disdain to recognize other types of bilingualism (e.g., indigenous languages) is evident during the implementation of these projects (Guerrero Nieto, 2009, 2010). Despite the focus on bilingualism processes around EFL in Colombia, other proposals from minority groups have come up considering a Spanish-minority language duet, since from colonial times this population has had that situation. Therefore, in the local context and abroad (South and Central America), IBE and ethno-education have arisen as a way for these communities to implement bilingualism programs using their mother tongue and Spanish (or Portuguese) as a means for their instruction in schools, and not the one imposed by the predominant sectors (English in the Colombian case). Only in this way it is possible to talk about inclusion and participation of all groups in political, economic or linguistic decisions of the country (Castillo & Caicedo, 2008; Fajardo, 2011; Lagos, 2015).

Interculturality

In Colombia, the government recognizes and protects the cultural and ethnic diversity of social groups that live in it, making the nation a multicultural context. Also, many indigenous groups have resisted over time and insist on maintaining their cultures and languages; then, these social groups coexist with the dominant culture and relate to it for educational purposes, legal aspects, and commercial issues, among others. These encounters between two individuals from different cultures are framed under the term interculturality (Trujillo, 2005, p. 33). This term has been widely discussed and is usually tied to the educational field and to social processes. According to Rehaag (2006, p. 4): “Interculturality is based on the argument that all cultures are equally valid, and in an attempt to understand the others, one comes to approach them and to face one’s own culture at the same time” (authors’ translation).

For her part, Walsh (2010, pp. 76-78) considers that the concept of interculturality can be seen from three different perspectives: a relational perspective, in which there is contact and interchange between cultures; a functional one, in which the diversity of cultures and the differences each one has are recognized in order to include them in the social structures already established; and a critical perspective that pretends to erase all differences so that new relationships among people can be created in order to transform the social structures that perpetuate the hegemonies of power.

These cultural encounters allow people to show the others who they are and how they conceive the world around them by using their language. As pointed out before, language and culture have a tight relationship, as stated by Delgado (2001) when arguing that a language can shape the culture where it is spoken, and that at the same time the culture gives the language particular elements to be understood. However, sometimes this relationship is not taken into account, especially in educational processes. In relation to this, Walsh (2010) considers that:

Within IBE, the intercultural aspect has been understood mainly in linguistic terms and in one direction only: from the indigenous language to the national one. And this direction gives interculturality a transition sense: It shows how indigenous students should have a relationship with the dominant culture and not vice versa. (pp. 80-81, authors’ translation)

Given this situation, it is important then to think about how educational processes take place in IBE in order to evaluate what has been done so far and to implement the necessary adjustments.

Conceptions of Education

Approaches to Western Education

Grasping the concept of education requires the understanding of many social and cultural relationships that contribute to the instruction of a person, as well as many other people involved in it. Therefore, León (2007) considers that education is conceived to evolve, not to be static; then, it must be redefined and questioned based on a determined time and space in which different subjectivities may share and build up knowledge. With that view, the educational process must not be standardized because, beyond the homogenized practices, it has to satisfy particular necessities in specific contexts.

According to Freire (2005), traditional education focuses on a “banking process” in which “students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor. Instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiques and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize, and repeat” (p. 70); thus, the most important role is exerted by the teacher who has the knowledge and transmits it to the student to be memorized. To counteract this situation, a dialogical education is offered with the sense of allowing students to become active participants in their learning processes; hence, one of the basic principles of critical pedagogy is the cooperation to construct knowledge without hierarchies; thus, “authentic education is not carried on by ‘A’ for ‘B’ or by ‘A’ about ‘B,’ but rather by ‘A’ with ‘B,’ mediated by the world” (p. 93).

To conclude, the education process should involve essential issues such as the construction of knowledge in a dialogical dynamic, the democratic participation to benefit expression of different points of view and, the dynamic sense it has according to particular contexts with precise needs.

Indigenous Self Educational System

For many years, the educational model to be implemented in the indigenous territories in Colombia was Western-like; as Betancur (2012) argues, the only education given for indigenous communities was the Western one through the imposition of the Spanish language and evangelization; so, subjects in the indigenous schools were taught in Spanish with teachers ignoring the mother tongue; Western knowledge was imposed over the vernacular one and with this comes the imposition of Catholicism. As a consequence, education was based on proper Christian conduct rules to guarantee obedience, abstinence, and work.

As the Western proposals were inadequate for the indigenous lifestyle, the Colombian native groups aimed to develop a “new educational” model in which their ancestral knowledge, meaningful practices, languages, and cultures were included in their programs; therefore, the “Sistema Educativo Indígena Propio, SEIP” (Indigenous Self Educational Model, IESM) was presented as a proposal to meet this end. Thus, the Comisión Nacional de Trabajo y Concertación de la Educación para los Pueblos Indígenas (CONTCEPI) (National Commission of Labor and Agreement of Education for the Indigenous Peoples) was created through government decree 2406 of 2007 in order for indigenous groups to start working on this educational model. CONTCEPI considers that it brings into practice the “law of origin, law of life, main right or proper right for every group, maintaining unity, the relationship with nature, with other cultures, with the hegemonic society and with each one keeping their own traditions” (CONTCEPI, 2013, p. 19, authors’ translation). Then, this proposal becomes a reality when “the wise men practice their knowledge in relation to their diverse surroundings, when we learn from our parents and the material and spiritual nature: the traditional medicine, rituals; the plowing of land . . . Yamana or community work, etc.” (CONTCEPI, 2013, pp. 20-21, authors’ translation)

Research Design

The current study followed a qualitative approach as it attempts to describe and contrast the ideas that both groups of participants have about education, bilingualism, and interculturality through their real experiences. Consequently, the Historic-hermeneutic paradigm was implemented since it pursues understanding the way in which the three concepts are assumed in different contexts. This understanding usually goes beyond the text (Data) because it also includes context and pretext to find the inner sense of what was said as this has something inside (Grondin, 1999).

The participants were two groups of teachers, five from a BA program in Bilingual Education from a private university in Bogotá, and four from an indigenous school located on a reservation in Puerto Gaitán, Meta (Colombia). All participants have been involved in the teaching of languages, either English-Spanish or Spanish-Sikuani so, besides being teachers, they are bilingual. All teachers working in the university studied for and completed a BA in languages and a master’s degree related to education. They have worked for this institution for more than three years and have had the opportunity to travel abroad fostering contact with the foreign language and its culture. The teachers from the indigenous context studied basic education, and some have started a BA program in ethno-education. Two of them have worked in the school for more than 10 years and the other two, about three years. They have been in contact with the second language (Spanish) all their lives. The participants were chosen by convenience, which means, people who wanted to contribute and feel an affinity with the topic under study participated in this research exercise. To carry out the research process, three instruments were used: focal groups, semi-structured interviews, and videos (Hernández, Fernández, & Baptista, 2006; Pujadas, Comas, & Roca, 2010).

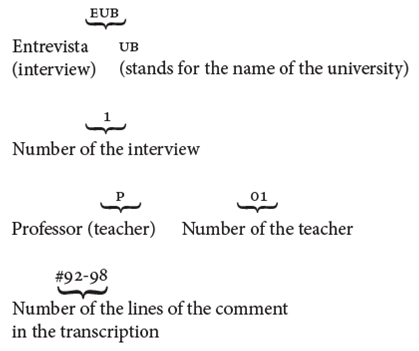

The research process followed the proposal from Taylor and Bogdan (1990), who establish three moments: discover, codify, and revitalize. In the first phase, topics are sought based on data collected; after the completed data collection process is done, it must lead to the categories for the analysis; and in the revitalization stage, data are interpreted within the context where they were collected. With the purpose of handling the data easier, they were coded as follows:

Example: EUB1.P01. #92-98

Other codes given to data are: EW = Entrevista (interview) Wacoyo and EG = Encuentro grupal (focal group).

Data Analysis and Results

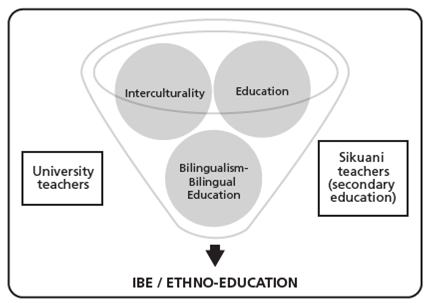

As the two groups of participants come from different realities in terms of their lifestyle and educational backgrounds, this research exercise attempts to identify the conceptions both groups have about three concepts: education, bilingualism, and interculturality, since these terms compose the IBE project or ethno-education, as it is called in Colombia. That is why the instruments used for this research project addressed the concepts mentioned before with the participants in pursuance of understanding what the idea was of the teachers about these terms and how they gave meaning to them in their educational contexts. Therefore, this part is divided into three main sections (education, bilingualism and bilingual education, and interculturality), which show the similarities and differences around the topics discussed for each group (see Figure 1).

Education

According to the collected data, it is possible to mention that the concept of education is usually linked, in both groups, as the teaching and learning processes a person is involved in, which in turn becomes a reproduction of the cultural structures and social models of the context. To this end, León (2007) argues that the educational process “cannot get rid of the culture and tradition (since) these show the values which give cohesion to the way of thinking and to the actions of the social systems” (p. 600, authors’ translation). Then, the educational process goes beyond an interchange of knowledge because it is also a way for culture, ideologies, and values to be perpetuated.

When talking about education, both groups consider it as a tool that bolsters and helps achieve some goals, which represent a social status such as economic capital and leadership. Particularly, for the university teachers, education becomes a way to ascend socially, to be recognized in the context, and to get better financial resources. In terms of Bourdieu (1986), people who have the opportunity to access education acquire a cultural capital (forms of knowledge or educational credentials) that later turns into economic capital such as money or properties; this capital is the stuff “of all other forms of capital and treats all others types of capital as transformed, disguised forms of economic capital” (p. 252). This idea of education as a way to access economic capital is referenced in the next excerpt:

As a teacher, I have seen that education can actually change the reality of a person; if I hadn’t had the education I have now, my possibilities would be reduced. I think that education has had a positive impact in my family in an economic and social way. (EUB1.P01. #92-98)

Then, for the university teachers, education offers the possibility to acquire better economic resources and social status, what in Bourdieu’s theory is understood as economic capital or goods a person possesses. This capital derives from the education people received that guarantees access to well-paid jobs in society and, consequently, a better way of life and socioeconomic conditions.

From the indigenous teachers’ perspective, education offers the possibility to become a leader. Then, the participants affirm that education helps to learn from the surroundings and to internalize the principles of community thinking, both of which are basic features of a leader, even when making decisions. Therefore, leadership is an ability to contribute to the development of the social group, so the leader should put the collective interests over the particular ones in benefit of the social development of the community. To this end, García Hierro (2015) mentions that leadership, in indigenous communities, is linked to the idea of “Asla Laka”, a Guatemalan indigenous word referring to the “Unity Law”, which is a way to highlight that community predominates over personal interests. To support this information a participant affirms:

Talking about education . . . education in our culture is not only to teach but for the kid to visualize what it is in his or her environment . . . in our community, leadership is a key point for the young people, so they understand they are part of a big community, not only of a small family. (EG1.PA. #430-440)

Hence, for this group of participants education is the way for a person to become a leader in their communities and in the nation; therefore, this is broader than learning about basic subjects established by the Colombian Ministry because it is a process in which the student learns personal abilities such as taking decisions, listening to the community, or negotiating with non-indigenous people, along with the required subjects.

To sum up the previous ideas, it is possible to infer that for both contexts, education is a process to achieve certain goals; however, the ends are not the same. Thus, for the university teachers’ group, education may grant them access to a better economic condition and thus a better quality of life which, under the interpretation of Bourdieu (1986), represents the acquisition of economic capital, reflected in the monetary resources owned by a person. On the other hand, for indigenous teachers, education becomes a tool to develop leadership, which is characterized in elements such as the ability to listen and to take decisions that benefit the community as well as one which also acts as an intermediary between this indigenous group and the dominant sectors of the society (Velasco, 2014).

After analyzing the goals education has in each context, we see that a new relationship emerged; it was the connection between education and experience. Then, for both groups this relation is direct because a learning process happens when people experience their surroundings in an interactive process. According to this concept, an indigenous teacher points out the idea that education is not only related to knowledge about science, math, language, and the like, but also to the experiences people have in their contexts, since they turn into situations for learning, as shown in the following excerpt:

In my case, the school was a place to confirm the information we were taught at home. For example, if I know that this is the word for fish and how it is pronounced, I go to the school and confirm this with the teacher. (EW1.PA. #961-974)

Based on the above, the relationship between education and experience leads one to think that the learning processes occurs both at school and everywhere; as a result, it is an interactive and constant process with all elements that surround a person. CONTCEPI (2013) considers that learning takes place with

our parents and material and spiritual nature: traditional medicine; rituality; farming; history; how to care of the seeds based on the moon calendar . . . the relation with the territory, rivers and mountains . . . learning to read the time and space, songs, music. (p. 20, authors’ translation)

Therefore, for the indigenous teachers, people experience the world by interacting with others and with nature, so, in this particular dynamic the learning process happens to help people restructure their knowledge and cosmovision in a constant process that never ends.

Likewise, teachers from the university context consider that experience is part of education because people learn through every single process in which they socialize or interact with others. That is to say, the experiential issues go beyond a formal or informal institution, because it is part of the daily interaction humans have. It is evidenced in the next excerpt:

Education is not only mentioning the types of education, like formal or informal, but to all experiences or socializing processes we have, or the different opportunities of learning that we may have. (EUB1.P02. #96-103)

According to this line of thought, in human interactions people gain knowledge; and as this process is part of daily life, people learn constantly in every moment and in different spaces. Moreover, education cannot be linked to only a particular place such as the school or the university, because it can happen in different places in which a person has the opportunity to interchange ideas with others (church, family, work, etc.).

To conclude this category, it can be said that there are some similarities in the answers provided by the participants; however, there are particular ideas that must be considered. First, one common idea is that education acts as a way to obtain a type of benefit. In the case of the university teachers it is represented as the economic capital (Bourdieu, 1986), which comprises the goods and money that derive from the education (cultural capital) a person has. For the indigenous teachers, education allows them to perform as leaders inside their territories and this is represented in issues such as listening to others, taking decisions, and developing community thinking. Then, for the university teachers the role of education is to empower the individual development which, in turn, provides economic capital; therefore for the indigenous teachers, education becomes a way for a person to gain a sense of belonging to a social group, and in this way, to help in the development of his or her community.

Another similarity refers to the relationship between education and experience and how they complement one another; at that point, both groups consider education as the experience in which one learns by means of interaction. Whereas university teachers consider that education is completely linked to the interaction among people, for the indigenous teachers this interaction is not only with people, but also with other elements such as nature and its components. In fact, even when both groups of teachers have similar ideas about education, when talking about its goals and its relationship with experience, the ideas become wider in issues such as individual (money) and community development (leadership) and experiential learning obtained from the interaction with humans and the components of nature.

Bilingualism and Bilingual Education

The second category allowed us to identify the perspectives the participants have about the concept of bilingualism and its role in education. The first aspect where the participants’ ideas converge is in the definition, corresponding to Skutnabb-Kangas and McCarty’s proposal (2008) wherein these authors state that bilingualism is the possibility for an individual to use two languages proficiently, therefore, “the term does not always imply an equally high level of proficiency in all the relevant languages” (p. 4); this perception is evident when an indigenous participant affirmed: “bilingualism implies that you should talk in two languages” (EG2.PA.#107-108), so this comment refers to the closeness to what is proposed from the theory with regard to the use of two languages. Evidently, we can emphasize the fact that, in the indigenous context, the mother tongue is Sikuani and the subsequent language is Spanish, as the following excerpt portrays:

We always specify which is the mother tongue and the second language as Spanish, they are always together, playing an important role. (EW2.PB. #57-59)

When the indigenous peoples talk about Spanish, they explain that their learning system of this language was depicted as an interactive process with mestizo people by means of work, education, and religion. As one of them stated:

Our grandparents did not talk Spanish properly, they started to use it when they went to work in the farms, around 1970’s. Then, education in Meta Department started and most of the families began to use Spanish, to become bilinguals. Also, Catholic religion started to evangelize, and Spanish was introduced in this way as well. (EW2.PB. #30-43)

Having shown the indigenous perception, we think here it is possible to mention the similar comprehension university teachers have about the concept; hence, one of them states that a bilingual person “is the one who has the communicative competence, not only in his or her mother tongue but in a foreign one” (EG2.P02. #21-23).

It is also important to remark that the definition is supported with academic authorities as declared in the following statement:

It comes to my mind a definition by Grosjean about bilingualism as the regular use of two languages in the daily life of a person. In my case, I may say that I am a functional bilingual, because I can use both languages in different situations, in different contexts. (EUB2.P03. #468-484)

The previous information is linked with the ideas of different authors which support that being a bilingual refers to the perfect domain of the L1 and L2, (Blanco, 1981; Lam, 2001; Romaine, 1999). However, according to Bermúdez and Fandiño (2016), recent studies suggest that more than categorizing bilingual people, it is imperative to describe and be precise as to “their psychological development, their cognitive organization, their communicative specificities or their relation with the cultural environment” (p. 45).

Another coincidence about bilingualism is related to its purpose because the participants understand the L2 as being a tool for communicating but each community uses it in a different way. For the indigenous participants, the second language allows them to defend themselves and to be recognized in the nation. It is clear that during indigenous meetings of diverse groups-known as Mingas-Spanish becomes the language to communicate among them. This enables them to participate actively and the Spanish language becomes the lingua franca inside the Colombian context. In this regard, a teacher mentioned:

In my case, for example, when all indigenous communities in Colombia gather together, the only way to communicate among all is by using Spanish as I cannot use my mother tongue. In that moment I start using Spanish because all people must understand me. Spanish gives us an opportunity to communicate with each other. (EG2.PA. #141-148)

In the same way, the indigenous teachers explain that Spanish becomes a defense tool in a nation as expansive/broad/diverse as Colombia. This is explained in the following extract:

…and then, due to the need of interaction with the others, they had to learn Spanish to demand their rights, so they were not robbed anymore; therefore, I see in bilingualism an opportunity for us not to be exploited anymore. (EW1.PC. #200-204)

Now then, from the university teachers’ perception, English is assumed as a language to reach certain progress because of the possibility the language gives us; regarding this point, it was affirmed that:

I think that most of us perpetuate the idea that the English language opens many opportunities, and the Ministry [of Education] has a very clear discourse about this. (EUB.P01. #1262-1265)

And, the idea is reaffirmed when stated:

I think that bilingualism is an interesting element, a factor that promotes the social and cultural growth, and it has to be linked to all social processes. (EUB.P05. #231-235)

The situation of bilingualism in Colombia was the third convergent axis mentioned during the conversations. Although most of the national context recognizes Spanish-English bilingualism, for the Sikuani community this feature is broadened because in their territories other indigenous languages coexist, turning this into a multilingual phenomenon. Thus, the participants explain that in school, although Sikuani is their mother tongue, Piapoco, Spanish, and English are also part of their realities:

For us, Spanish is our second language and as we will study English, we would have three languages; for example, there is a teacher who speaks Sikuani, Piapoco, and Spanish, if he studied English, he would have more opportunities. (EW2.PA. #131-136)

The group of university teachers recognizes that the bilingual policy implemented in Colombia considers Spanish-English, but other bilingual forms are forgotten, as explained:

I think that the policies regarding bilingualism are focused only on the English-Spanish duet, disregarding other foreign languages or indigenous languages as well. This has led us to consider bilingualism only from that English-Spanish point of view. (EUB1.P02. #344-356)

Although the Ministry of Education recognizes bilingualism, both groups of participants agree that there is no recognition of other languages different from English, even though there are other bilingualism processes, such as the ones among minority languages (indigenous, Romani-from Gypsy people-, Palenquero, and others) and between them and Spanish. This occurs because as regards the Ministry of Education, the policies related to ethno-education are distant from the bilingual programs because, as Fandiño and Bermúdez (2016) explain, there is a distance created in the educational system since the term “bilingual education is used to refer to educational programs involving the teaching of English, French, or German, and the concept of ethno-education is applied to education related to minority languages” (p. 146, authors’ translation).

As a conclusion, it is evident that both parts agree in the conceptions they assume about bilingualism, especially regarding the managing of two languages. Nevertheless, it would be relevant to think the bilingual phenomena raised by the Ministry of Education, which only bears in mind the relations of dominant languages, are to explore the national linguistic diversity of the country. Then, in the Colombian context it is relevant to recognize not only the bilingual duet English-Spanish, but also other forms of bilingualism or multilingualism that constantly exist in indigenous reservations.

Interculturality

In this category, it was also possible to observe that both groups of teachers shared a common definition of interculturality that is related to the knowledge and cultural practices, interaction, and exchange to find points in common, but they bring it to their realities in different ways. According to Trujillo (2005), interculturality refers to “the encounters in which two people who perceive themselves as culturally different get in touch with each other” (p. 33, authors’ translation), a definition that comprises the ideas of the participants, especially for the indigenous teachers, for whom interculturality deals with the interchanging of knowledge in order to converge into common points of view, as the following teacher mentions:

I can also share my knowledge that is not known by everyone of you, and it happens the same with a Spanish speaker with his or her mother tongue and his or her culture. Then, if he/she has a culture, it shows a different point of view; then when we start doing interculturalization, we contribute, you contribute, and we always look for a single conclusion. (EG2.PA. #166-174)

The group of university teachers understands interculturality in a similar way to the indigenous one; therefore, they mention that in order to understand some cultural practices, interaction plays an important role, as mentioned below by a teacher:

I would ideally think that interculturality is the interaction between two or more cultures, the interaction between different cultures. (EUB2.P03#1148-1152)

This interactive process has an important function in representing one’s culture without invalidating others’ cultural backgrounds.

Another important issue to consider is the relationship between interculturality, respect, and cohabitation of people in school. Therefore, indigenous teachers consider this as a key element since they argue that their school integrates students with different experiences whose meaning are in constant negotiation. Regarding this matter, it is commented:

On the other hand, if a peasant, a gypsy, or a person from a specific group, comes to study at our school, we cannot segregate him/her because the idea of interculturality points towards integration. (EG1.PB. #260-267)

Consequently, when talking about integration and cultural interaction, the importance of respecting the language and culture of the participants in a communicative act must be recognized, so that all people involved get a sense of impartiality. That is to say, when interacting in a different context from which a person comes from, it is necessary to negotiate meanings respecting the cultural and linguistic rules to guarantee egalitarianism. This is one way to state it:

Interculturality tries to associate different social groups because in Colombia there are more than 68 ethnic groups; but if I want to go to study the Piraroba or Piapoco languages or any other, I have to interact with that group, respecting their statutory rules; and when other group comes to study with us, it has to do the same, always respecting, not excelling, but respecting the language they handle. (EW2.PB. #276-287)

Also, participants from the university consider interculturality as an interactive process that takes place within a territory in which respect and tolerance for the other should be a must, because everyone has a particular background that makes him/her different from the others:

But I think that if there is interculturality, there is respect for diversity, there is respect for difference, so, I think that it would be the key to interculturality; to understand that there is another culture that is different from mine, that has another language, other customs, another ethnicity maybe, another race, but for these reasons they are not more or less valuable, there should not be like those power dynamics between one culture and the other if there is interculturality. (EUB2.P03#1152-1166)

According to the above, an intercultural process recognizes the respect for diversities not only in terms of race, but also in the way of thinking, the language, and cultural practices, among others. For some researchers, interculturality takes place when one recognizes one’s own culture and the one of the others within a framework of acceptation, acknowledging the other in his/her differences. Thus, Rehaag (2006) mentions:

The concept of interculturality is based on the fact that all cultures are equally valid, and in a process of mutual understanding an approach to the “other” or “stranger” is carried out, which at the same time involves a confrontation with one’s own culture. (p. 4)

Another aspect to look at is the way both groups bring this concept to their realities. Even though all the participants consider interculturality as the interaction that takes place between two cultures, university teachers think about it from the theoretical or academic contexts, as a way of implementing a course or a space to teach what the concept means:

In our system we do not have a class about worldview or interculturality; then, it is not thought as reflection towards our own culture, perhaps because it has been thought that the need does not exist, but that is debatable, I think. (EG1.P01. #282-287)

Likewise, another teacher expresses that even though language and culture have a close relationship, bilingual schools in Colombia seem not to have a cultural component of the target language, so, the intercultural awareness is not reinforced because the predominant model is related to the linguistic skill.

Here [in the Western context] it is thought that in bilingual school, you are taught English, you are taught only a language, but I have never heard, at least where I worked, or with my nephews and close children I know, that the school will teach them about culture; then, English is shown as a hook, as a plus. (EG1.P03. #413-418)

For the indigenous teachers, in contrast, interculturality is a living concept that is not only promoted in school because it is part of the everyday nature; this could be revealed in the experiences when non-indigenous people go to the reservations to interact with the community, then the sharing knowledge process is mediated in the Spanish language as a way to deeply recognize the others’ practices and cosmovision.

Also from the language, the food; many people go there (Wacoyo) and they are not indigenous, then, how can we interact in our language if they are not going to understand us? Then we have to use Spanish. That is why we always learn and teach boys from the youngest and the oldest. (EG3.PD. #92-96)

To conclude, it can be said that the concept of interculturality is understood by both groups of teachers as the interaction of two cultures in which respect for each one and their world visions must mediate to share knowledge. However, each group experiments this concept in a different way: indigenous teachers can have a lively and close experience with other cultures, but university teachers need to approach the concept from theoretical and school contexts. As regards this topic, Trujillo (2005) explains that there are two visions of culture: Culture with a capital letter and culture with a small c, because the former comprises all art elements as music or literature, history, customs, and the like, which can be learned and studied, as in the case of university teachers. The second way to approach a culture (with a small c) relies on experiencing the beliefs, values, religious views, moral aspects, linguistic and non-verbal elements of the language, and others, which the indigenous teachers have had the opportunity to live.

Conclusions

The benefits of the interchange of knowledge between the participants in this research are relevant because not only they could recognize each other’s point of view but also because many commonalities were found along the discussion of the three categories: Education, Bilingualism and Bilingual Education, and Interculturality. Likewise, this sharing of points of view allowed the participants to enrich their perceptions about topics related to the concepts; therefore, different perspectives and perceptions about education and pedagogy were explored to promote the personal and academic practices in favour of inclusion, visibilization, and diversity.

For the category of Education, a common aspect among the participants is the idea that educating a person deals with the interaction he or she has with his or her context and how he or she makes sense of the world based on that; that education should transcend the classroom to every space and experience for the well-being of the person. Also, the participants of this investigation consider education from different perspectives: for university teachers, education is conducive to acquiring economic capital whereas for the indigenous group it is a benefit represented in leadership.

In relation to Bilingualism, both communities agree that this concept is related to the use of two languages in a context, as seen in the participants’ comments. This idea is supported by different linguistic theories; however, for the indigenous teachers, Spanish as their second language becomes a tool to defend their rights and be recognized in the hegemonic culture, as well as a channel to communicate with other indigenous communities. For the university participants, the use of the foreign language (English) allows them to access better academic and working possibilities within what has been called “a globalized world”.

Finally, interculturality is perceived in both groups as the contact of two cultures in equal terms for them; nonetheless, in the western culture working with it can be done through courses, seminars, and the like, and the access to the foreign culture can be done through books, movies, and songs, among others, since a move to English speaking countries is most of the time difficult. On the contrary, for the indigenous community interculturality is a living process due to the closeness to the second language culture which lets them interact and share their knowledge and cultural practices.