Introduction

The development of advanced writing skills in English as a foreign language (EFL) is a key factor in professional development in general; writing is a major tool for transmitting and disseminating knowledge in a globalised world where English is considered the universal language. Thus, mastering this skill is compulsory for students of the initial English language teacher education (IELTE) programmes in Chile. Nevertheless, “standardised tests of students and teachers have consistently demonstrated relatively low achievement” (Barahona, 2015, p. 7).

In 2014, the Chilean Ministry of Education created the Guiding Standards for English IELTE programmes in Chile (Ministerio de Educación, 2014), which outline the linguistic and pedagogical competences that future teachers of English need to develop during their undergraduate programmes. One of them is the competence of oral and written skills as well as an advanced level of English at the time of graduation: C1 according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFRL).

During the 1990’s, the curriculum of English language at schools placed stress on the “development of listening and reading comprehension skills, giving speaking and writing a subsidiary role” (Ormeño, 2009, p. 7). Students from this system are then enrolled in the IELTE programmes, which means they learn how to write in English at university level. Therefore, the pressure is on teacher educators who need to develop academic writing with beginner students (Level A1 from CEFRL) who are not familiar with writing in EFL at all.

Writing portfolios uses the process approach to develop writing skills through multiple drafting, authentic and meaningful tasks, and systematic feedback. However, most studies that use portfolios to develop writing skills focus on learners of EFL but do not specifically consider pre-service teachers and their perceptions (Aydin, 2010b; Lam, 2013; Song & August, 2002). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions are important since perception refers to the process of attaining understanding and awareness of the process of portfolio keeping (Aygün & Aydin, 2016).

This study aims to investigate the perceptions of students towards portfolio keeping in an IELTE programme in terms of its benefits and challenges for pre-service teachers.

This study aims to answer the following research questions:

Literature Review

Writing Portfolios in EFL and English Language Teacher Education

Portfolios are widely used in education, and since the 1990’s they have also been introduced in the teaching of English as a second language (ESL), mainly in the United States of America (Pollari, 2000). As a result, in Latin America and specifically in Chile, there is not a robust body of research on this topic. In the particular case of English language teacher education programmes, portfolio keeping not only constitutes a strategy for learning, but a future strategy to be considered in pre-service teachers’ own pedagogical practice as future teachers of English. Regardless of the importance of portfolios, a limited number of studies have been conducted in Latin America (Delmaestro, 2005; Lunar, 2007; Perdomo, 2010; Saavedra & Campos, 2018) and little research seems to have been published in Chile.

According to Richards and Renandya (2002) a typical portfolio contains the student’s total writing output to represent their overall performance. Furthermore, portfolios constitute a learning and assessment strategy which provide deeper insights into students’ own learning processes and their academic improvement because they cover an extensive period of time, usually one term or a whole year.

Contributions of Writing Portfolio Keeping

Portfolio keeping has a number of benefits, as underlined by Brown and Hudson (1998), who state that “portfolio assessment strengthens learning by increasing learners’ attention, motivation, and involvement in their learning processes, promoting student-teacher and student-student collaboration and encouraging students to learn the metalanguage necessary for students and teachers to talk about language growth” (p. 664).One practical perspective is whether writing portfolios contribute to students’ learning. Students taking responsibility to plan, evaluate, and monitor their own language and self-regulated learning to become autonomous are examples of the practical benefits of writing portfolios (Barootchi & Keshavarz as cited in Burner, 2014). Besides, Hamp-Lyons and Condon (2000) claim that “portfolios are particularly beneficial for foreign language learners because portfolios provide a broader measure of what learners can do, and they replace timed writing evaluations” (p. 61).

Another important issue for learners of English, and specifically for teacher trainees, is that students have the constant possibility to become active participants of their learning process and monitor their own progress. As Hirvela and Pierson (2000) discuss in their study, through self-reflection and self-assessment, students can attain an awareness of their own learning processes, thus fostering motivation and engagement in such processes.

Similarly, the opportunities for feedback are greatly expanded in teaching with portfolios. First, there is the opportunity for several drafts of each piece of writing-the process writing approach that is so fruitful for feedback-enhanced by the possibility of revisiting and revising the piece of writing further during the semester (Hamp-Lyons & Condon, 2000). Finally, as Barret (2000) states, portfolios promote collaboration between students and teachers, and among peers. The portfolio allows a visualisation of the progress of students throughout the learning process according to the complexity and progression of their educational performance. It also promotes collaboration among peers through feedback and teacher support for the construction of the final product (Barret, 2000).

Learners and Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions of Writing Portfolios

It is important to know pre-service teachers’ perceptions of writing portfolios since the way these specific learners perceive the strategy might determine their success or failure. Consequently, if pre-service teachers have a negative perception of the strategy to develop writing, the less likely they are going to use it in their future teaching practices. This section will present both positive and negative appraisals of the benefits and challenges of portfolio keeping.

Nunes (2004) conducted a case study for a year with high school students in Portugal, which aimed to shed light on students’ reflections and involvement in the teaching-learning process. Nunes states that “portfolios help EFL learners monitor their own learning and become more autonomous”. She also claims that “portfolios can be used as pedagogical tools to facilitate the use of learner-centred practice” (p. 334).

In addition, the study carried out by Paesani (2006) presents a writing portfolio project which reported that portfolio keeping helps students “to integrate the development of proficiency skills, content knowledge, and grammatical competence” (p. 618). A different study based on pre-service teachers’ and teachers’ perceptions on portfolio keeping (Aydin, 2010a) revealed that pre-service teachers particularly improve vocabulary knowledge, grammar and reading skills, organisation of paragraphs, and composition.

Lunar (2007), in her case study of 20 students from an English for specific purposes (ESP) course in a university in Venezuela, examined the impact of the portfolio in writing production in EFL. The findings indicated that students were reluctant at the beginning of term, but later, most of them valued their portfolios and declared that they had improved their vocabulary knowledge because of the use of vocabulary lists, their writing of formal letters, and their overall attitude towards the course. In a study conducted in Hong Kong with first year students at university level, Lam (2013) examined the impact of two portfolio systems in writing, namely showcase and working portfolio. The findings evidenced varied students’ reactions to the portfolio experience. Some students had a positive appraisal indicating that it helped them in discourse-related concerns. However, there was little agreement on the perceived effectiveness of peer feedback and self-assessment; some learners described it as a cognitively challenging activity while others indicated that peer feedback did not help them to improve grammar accuracy and that self-assessment was not efficient since they were not able to locate their own errors and did not understand why they had made them in the first place.

Aydin (2010b), in his study examining the perceptions of portfolio keeping of 204 EFL learners at university level, showed that students found the process tiring, boring, and time consuming. In addition, some students had difficulties providing peer feedback and carrying out pre-writing activities. Likewise, Lam (2013) concluded that students were not convinced of the benefits of self-assessment and peer feedback as part of the writing portfolio.

To conclude, in order to use portfolios effectively in English language teaching (ELT), potential challenges of portfolios should be taken into consideration. Brown and Hudson (1998) itemised the challenges of using portfolios under five categories that can influence portfolio implementation: design decision, logistics, interpretation, reliability, and validity.

Method

Design

A mixed methods approach (Creswell, 2009) was employed in order to gain insights into the perceptions of students about keeping writing portfolios. As Miles and Huberman (as cited in Dörnyei, 2007, p. 42) indicate, “quantitative and qualitative inquiry can support and inform each other. Narratives and variable-driven analyses need to interpenetrate and inform each other”. Thus, the results from the questionnaires can be strengthened by students’ opinions and analysis in the focus group.

Setting

The study was conducted at a university located in southern Chile. In general, students only have direct contact with English-speakers at university with language assistants from different English-speaking countries.

Students are enrolled in an IELTE programme where they study for five or six years to get a bachelor’s degree with which they are certified to teach at high school level. Pre-service teachers’ syllabus includes: English language, phonetics, literature, grammar, linguistics, didactics and curriculum planning, as well as a research project and a semester-long internship at a high school (from grades 9-12). Each course lasts one semester, which is seventeen weeks long.

Participants

The participants (n = 51) were students in the second semester of the IELTE programme and were assigned randomly to three intact groups at the beginning of the second semester of 2016. This distribution was organised by the university and does not correspond to their level of proficiency or any other variable. Students were in the age range of 18-30 with an average age of 20.6, whilst 58.8% (30) were women and 41.2% (21) were men. Results from the Quick Placement Test (QPT) given to all entering students showed that most of them had a pre-intermediate level of English (B1 according to the CEFRL) and were enrolled in their second English language course out of eleven-all compulsory. Students have to prepare throughout the programme to sit for the official CAE from Cambridge University in semester 9-as previously mentioned, and this proficiency level is a graduation requirement of the Chilean Ministry of Education.

This was a ten-hour per week course, where the four skills of the language were integrated. However, a two-hour writing session was established within the course for the purposes of this study. The participants were given a written consent form indicating that completing the questionnaires and participating in the focus group to collect data were purely voluntary acts and their answers would have no positive or negative impact on their mark for the course. All students agreed to the terms and signed the form.

Implementation and Procedure

The implementation phase was carried out by three teacher educators, of which two were also the researchers. One teacher had previous experience using e-portfolios for professional development and trained the team. The participants were students who had just entered the university, so they had not had previous experience with this type of methodology. Thus, they had explicit training sessions to understand the whole procedure.

The EFL writing portfolio is a physical folder that contains all the writing tasks students do in class, including first drafts and improved versions. The aim of this methodology is that students can keep a visualisation of their progress throughout the learning process according to the complexity and progression of their performance (Barret, 2000). Besides, it is important to mention that the researchers made the decision to use a pen and paper portfolio since they had diagnosed several shortcomings concerning basics of good writing among which are paragraphing, handwriting, punctuation, and spelling.

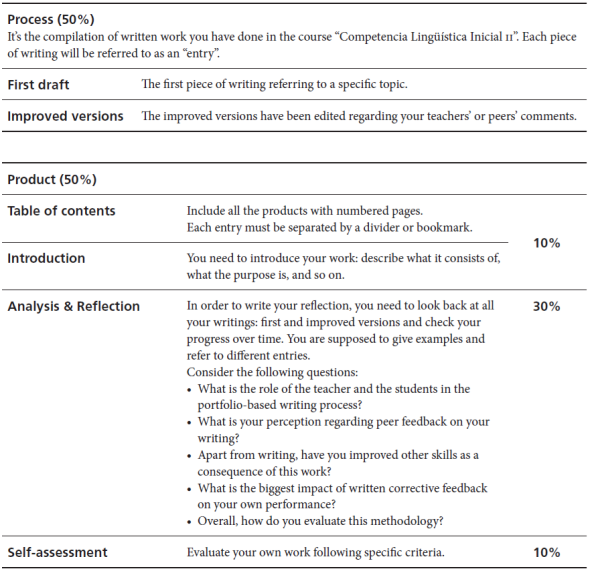

The writing portfolio innovation is made up of the following steps which are explicit in the general guidelines, which were developed for this study and validated through expert judgment (see Appendix A):

Writing texts: All the written work done in class during the semester which includes three drafts of each writing text.

Format: (a) An introduction and a list of contents, (b) each entry (writing text) must be separated using a divider or a bookmark.

Analysis and reflection: At the end of each term, students need to analyse their writing performance, improvement, and attitude throughout the writing class. Some specific questions are given to guide students’ reflection.

Self-assessment: At the end of the semester, students need to evaluate their writing skills process regarding language development, vocabulary usage, and time organisation, among other specific criteria.

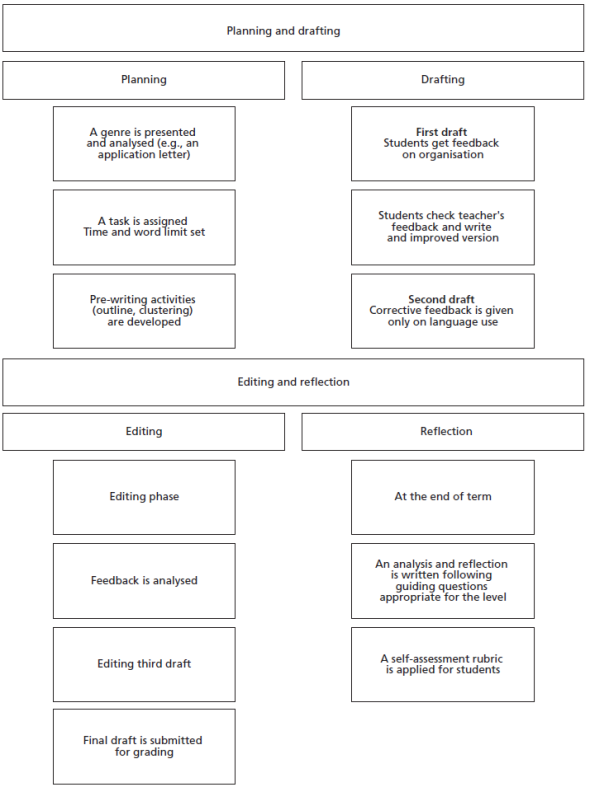

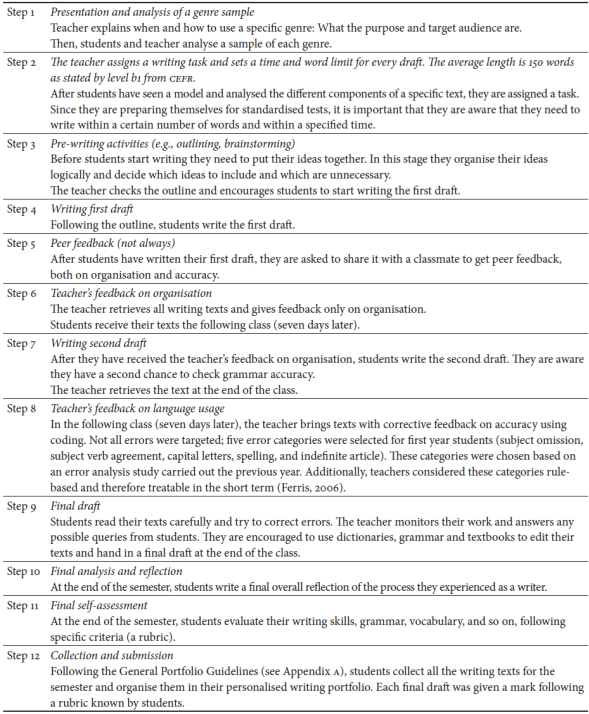

The writing portfolio procedure is summarised in Figure 1. However, a detailed description of the whole procedure is found in Table 1.

Table 1 EFL Writing Portfolio Procedure

Note. Steps 1-9 are repeated three or four times, depending on the amount of writing texts included in the term.

The procedure of the writing portfolio is repeated three or four times during the semester, with different text types. The process presented in this study included four text types: (a) a film review, (b) a biography, (c) a short story, and (d) an application letter.

Data Collection

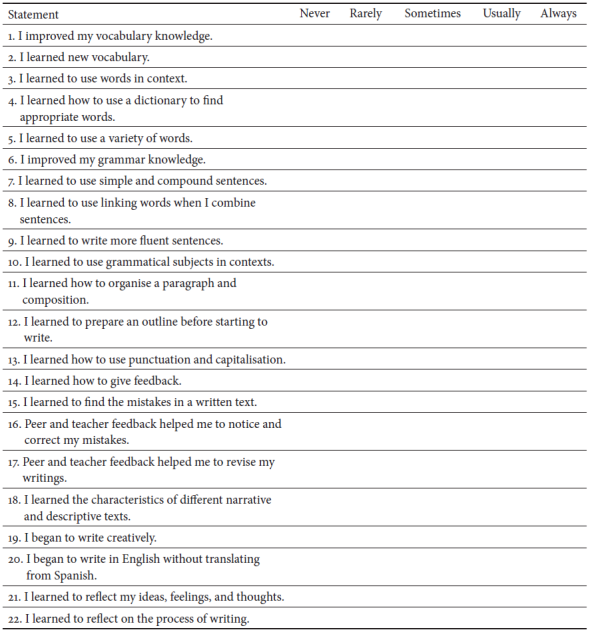

Data were collected post-portfolio implementation, after the seventeen-week intervention had finished. Firstly, the quantitative approach comprised a Likert scale questionnaire to get pre-service teachers’ perception on how much they improved their linguistics knowledge, writing, and reflection skills (see Appendix B). As Dörnyei (2007) establishes, these tools have proved to be simple, versatile, and reliable. Besides, reaching a wider audience is one major benefit of using this tool. This questionnaire was adapted from Aydin (2010b). This instrument met the requirements of this research since it included the focal aspects of the study (grammar, vocabulary, text type knowledge, and feedback). The adapted questionnaire for this study had a Cronbach Alpha of .897, which indicates a high reliability coefficient for the Likert-type scale used in this study.

The instrument has 22 statements and five categories. Some statements referring to grammar structures which had not been covered in the course because of students’ proficiency level were eliminated as well as statements relating to reading skills. Students needed to evaluate the statements using five options: never, rarely, sometimes, usually, and always. The survey items cover these areas: vocabulary knowledge, grammar knowledge, paragraph organisation, mechanics, feedback and correction, textual types knowledge, and reflection skills.

The questionnaire was administered to a six-student sample from a different cohort to check coherency and understanding, but no changes were made. Afterwards, it was given to all 51 students who were asked to write their names and year of enrolment. Thirty minutes were assigned to answer the questionnaire and students were encouraged to write comments on their experience.

On the other hand, the qualitative approach gave more insights into the quantitative data and was conducted through a focus group. In applied linguistics, qualitative research opens the door for a situated in-depth analysis of the factors affecting language acquisition. (Dörnyei, 2007).

A random sample of ten students participated in a focus group. It was conducted in English by one of the teachers from the programme who was not part of the project. It was a semi-structured interview which was recorded and later transcribed.

Data Analysis

First, the questionnaire data were analysed using descriptive statistics since, as Dörnyei (2007, p. 213) discusses, descriptive statistics help us summarise “findings by describing general tendencies in the data and the overall spread of the scores, and such statistics are indispensable when we share our results”. The data were processed using the programme SPSS 15.0 where the following values were assigned: never (0), rarely (1), sometimes (2), usually (3), and always (4). Descriptive statistics tests were applied: frequency, media, and standard deviation were calculated as to show the general tendencies of data.

The focus group was recorded, transcribed into a word document, and analysed using content analysis. The analysis was carried out step by step through the formulation of inductive categories of the data which were later split into subcategories (Mayring as cited in Cáceres, 2003). Some usable quotes were selected in order to contribute to answering both research questions.

Results

The findings from the study will be presented in two sections so as to answer the two research questions set out for this study.

Benefits of Portfolio Keeping in the Development of Writing Skills

Questionnaire Results

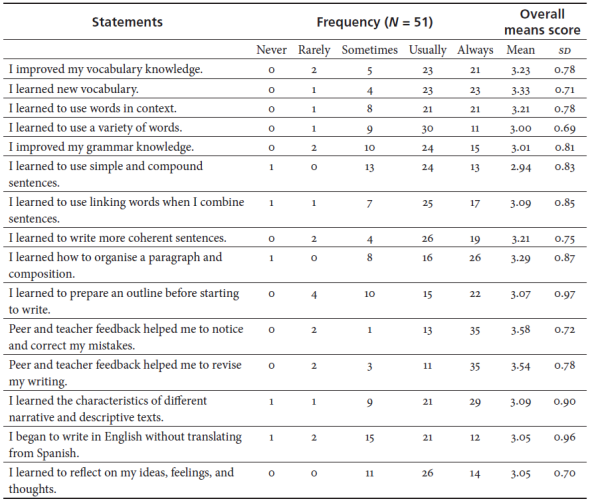

First of all, in order to consider that the portfolio was beneficial for a specific item, the sum of the categories usually and always had to have a frequency higher than 75%. A lower frequency (≤ 75%) was considered a challenge for the purposes of this study.

The main quantitative findings are summarised in Table 2; it can be observed that 15 out of 22 items (68.1%) had a highly positive appraisal by learners. Participants reported that keeping a writing portfolio in an IELTE programme contributes considerably to vocabulary knowledge in 44 out of 51 students (M = 3.23, SD = 0.78), especially learning new vocabulary, where 46 students out of 51 indicated they had acquired new words (M = 3.33, SD = 0.71) and using it in context. Additionally, learners indicated they improved their grammar knowledge in general, they learned to use linking words to combine sentences; 42 students indicated they usually or always learned how to do this (M = 3.09, SD = 0.85), to use simple and compound sentences (37 students chose usually or always), and to use grammar in context (39 students had positive perceptions). Moreover, learners considered this pedagogical strategy had an impact on their writing skills; namely, how to organise a paragraph in a composition (M = 3.29, SD = 0.87) and to a lesser extent, to develop pre-writing activities, mainly outlining with 37 students appraising this writing stage (M = 3.07, SD = 0.97).

An important aspect of the writing portfolio strategy is giving and receiving feedback. Pre-service teachers perceived that feedback from the teacher had contributed positively in revising their written texts; 48 out of 51 students perceived it as positive (M = 3.54, SD = 0.78). The categories regarding teacher feedback had the highest means of the questionnaire. Moreover, 40 students stated that using the portfolio contributed to the knowledge of different descriptive and narrative texts (M = 3.09, SD = 0.90) and the same number considered it helped them to write in English without translating into Spanish as well (M = 3.05, SD = 0.96). In sum, students perceived the writing portfolio as a teaching and learning strategy that allowed enhancing their vocabulary and grammar knowledge, as well as text organisation, text type knowledge, and reflection.

Focus Group Results

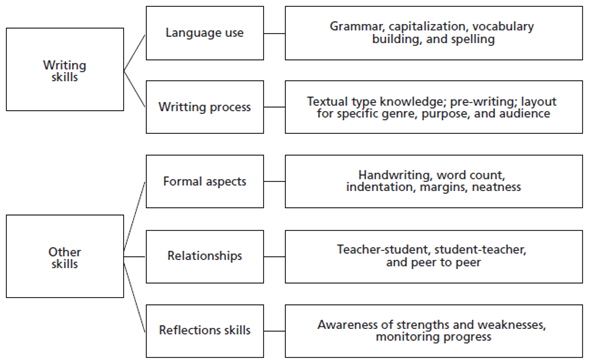

Two broad themes emerged from the analysis: writing skills and other skills (see Figure 2). Each theme has subthemes which will be presented and some examples from the interviews provided.

First, pre-service teachers mentioned they improved grammatical aspects, use of capital letters as well as expanded their vocabulary and spelling-they learned spelling rules.

The portfolio has helped me to improve my ideas, vocabulary, and more things. Since the first writing that I did, I’ve improved a lot, but I still have the same mistakes like: spelling or missing word but I had more before and they’ve disappeared. I didn’t have problems with capital letters anymore.

Similarly, they furthered their knowledge of text types-namely, descriptive and narrative and the different genres associated with them. In addition, they valued pre-writing activities and establishing the target audience and the purpose of the text before starting the writing process.

[The outline] gives you an idea of the general structure, so you don’t have to think too much while writing. It helps me not to waste time thinking what to write while in the process of writing.

Surprisingly, pre-service teachers valued other aspects related to the writing process. To begin with, they drew special attention to the improvement of formal aspects of writing, such as handwriting, margins, use of indentation, word count, and overall neatness in their work.

The process was interesting, I really liked it, it wasn’t easy though, there’s much more to be improved. I enjoyed the fact that I improved my handwriting a little, and that little is going to escalate into something bigger in the next year.

Furthermore, learners showed a positive appraisal of class environment and relationships among all the participants of the process who helped each other, which was not expected at university level, and finally and extremely important, peer to peer. According to them, these relationships grew closer because of the constant and systematic feedback they received from teachers and peers.

I think that it is a good strategy, I mean, we don’t do that a lot. But I think that it is good because with a partner you feel more confident, and feedback will be easier like when we go to the teacher we are always afraid about the things that she could say, like “No! This is past, it’s continuous”, I don’t know...But with a partner there is more freedom…I don’t know, more confidence.

The feedback given by the teacher and peers is very important, we could see in what we failed and the things that were missing.

A final aspect emphasised in the interviews was reflection. Learners said they had gained awareness of their own progress, thus being able to identify their strengths and weaknesses as they monitored their work.

I think the best thing about the portfolio was the...eh...I can read my older tasks and realise my mistakes, so I can improve or evade these mistakes in the future task.

Well, besides learning different structures, emmm...see the improvements that I have, like go 3 pages back, and then forward and see the improvement; I think it’s the best thing for me of the portfolio, to...to analyze my process, to have it all.

Ultimately, the writing portfolio methodology contributed not only to enhancing writing skills in pre-intermediate pre-service teachers, but also to complementing other aspects of learning which are as valuable to the whole process of writing in English.

Challenges of Portfolio Keeping in Developing Writing Skills

Questionnaire Results

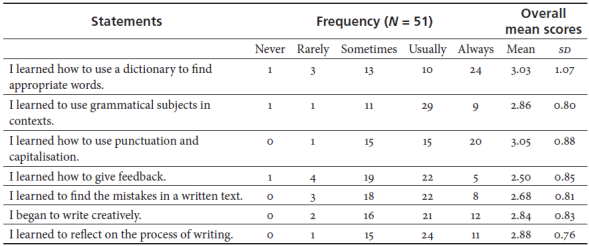

From the questionnaire, seven items (21.8%) were considered beneficial under the categories sometimes, rarely, or never (see Table 3). Therefore, these categories became a challenge for both teacher educators and students in the implementation of the class innovation strategy.

Surprisingly, using a dictionary to find appropriate words was perceived by pre-service teachers as a skill which was not highly enhanced by portfolio keeping and needs further training, and 17 students perceived they used it sometimes to rarely (M = 3.03, SD = 1,07). Additionally, 16 students indicated that sometimes or rarely they improved the use of capital letters and proper punctuation (M = 3.05, SD = 0.80) during the portfolio-based writing class. Besides, 24 learners believed they sometimes or rarely learned how to give feedback to their peers, and 21 students chose rarely or sometimes (M = 2.50, SD = 0.85); consequently, they could not find mistakes in the written texts from their peers (M = 2.68, SD = 0.81). Finally, a borderline category refers to learning how to reflect on the writing process where 11 students indicated that they rarely learned how to reflect (M = 2.88, SD = 0.76). Students believed they were not able to do it properly without the help of the teacher.

Focus Group Results

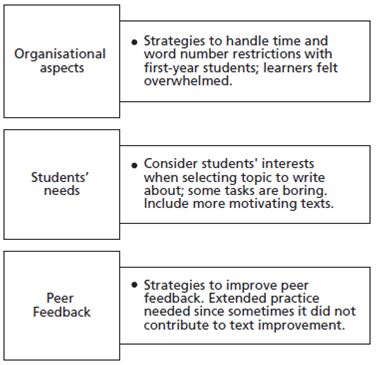

A number of challenges were identified from the use of a writing portfolio (see Figure 3); these categories will be analysed and some examples provided.

First, students referred to organisational aspects like time and word number limitations; they highlighted being under pressure trying to fulfil the external demands when writing.

I think that I don’t like the pressure of that, of doing...I like to write but the pressure of doing a specific topic is kind of hurrying me a little and I can like collapse and don’t like that.

The length, because I always say it...because I said I really...I wrote...I write more than the teacher asks me, so I don’t know how to reduce on that and do a short story of 200 words.

Secondly, learners noted that some of the topics they had to write about were not interesting or motivating for them. Thus, they felt their needs were not taken into consideration when planning instruction and they requested more freedom to choose topics on their own.

I would like to write about something that is interesting for me, because sometimes the topics are very boring.

Thirdly, even though they considered peer feedback as a helpful and positive activity for learning, they admitted they needed to be more skilled and experienced so as to have an impact on their peers’ revision process. They expressed they would like to have extended practice so as to advance on the matter.

Discussion

This study focuses on pre-service teachers’ perceptions towards the benefits and challenges of writing portfolio keeping in EFL in Chile. This article presents an innovation practice: its design and implementation throughout a 17-week semester at university level and a collection of the learners’ work during this period so as to monitor their progress, which is in agreement with previous studies on the use of portfolios (Burnaz, 2011; Hamp-Lyons & Condon, 2000; Richards & Renandya, 2002).

The main results to emerge from both quantitative and qualitative data were related to benefits and challenges of the portfolio as a strategy. The benefits can be broadly categorised into two areas: (a) development of writing skills, namely vocabulary and grammar knowledge, text organisation, and composition and secondly; (b) enhancing other skills like formal aspects of writing, collaborative relationships among teacher-learners and from peer to peer, and to some extent, reflection skills. On the other hand, the challenges identified by pre-service teachers are related to specific grammatical issues, particularly punctuation and capitalisation; organisational aspects and students’ needs; and finally, the process of peer feedback.

The results of this study contribute to the existent literature in regard to pre-service teachers’ perceptions of keeping a writing portfolio to enhance writing and reflection skills. Most importantly, these learners can reflect on the potential contributions of this strategy as future teachers of English with their own students.

Benefits of Writing Portfolio Keeping With Pre-Service Teachers

The main benefits revealed were related to the improvement of writing skills, more precisely grammar and vocabulary knowledge. Students perceived they had enlarged their vocabulary and were able to use the new words in context. These results are similar to Aydin (2010a), Lunar (2007), and Paesani (2006). However, Lunar (2007) incorporated the use of vocabulary lists on different contents as a strategy of the portfolio, which was not done in this study, and students learned new vocabulary using different personal learning strategies without keeping a record. Grammar competence also seemed enhanced by pre-service teachers, particularly the use of linking words and their knowledge of simple and compound sentences. The use of connectors is highly valued in this writing course and students are encouraged to use them as much as necessary; there is specific training considering this aspect of cohesion which, in turn, contributes to the use of compound sentences at the pre-intermediate level (B1). Aydin (2010a) also reported a perceived increase in students’ grammatical competence and proficiency skills in his study.

Another important finding is students’ positive perception on their improvement in paragraph organisation, which is similar to Aydin’s (2010a) reported results. A considerable emphasis is placed on pre-writing activities by teacher educators so as to help students organise their paragraphs around one central idea. The pre-writing stage is time-consuming and sometimes neglected in the writing process; however, students now realise how crucial it is.

One unanticipated finding was that students valued equally other aspects related to their writing process as writers of EFL. As first year students, they faced new requirements in academic writing regarding formal aspects (neatness, formatting, and word limit), which they found difficult to adapt to at first, and eventually the writing portfolio as a learning strategy helped them to deal with it. Furthermore, relationships in the process played an important role for them (teacher-student, student-teacher, student-student), primarily on a personal and affective level.

Finally, as prior studies have noted (Hirvela & Pierson, 2000; Nunes, 2004; Saavedra & Campos, 2018), writing portfolios in EFL contribute to the development of reflection skills. A regular practice of reflection can encourage renewing students’ commitment with their own process of learning for the sake of identifying, assessing, and planning next directions (Huber & Hutchings as cited in Zubizarreta, 2009).

For pre-service teachers it is a crucial skill and advisable to start working by reinforcing critical reflection at early stages. At this level of proficiency (level B1), EFL learners in the study showed to have a lower descriptive level of reflection, gaining awareness of strengths and weaknesses as writers, and at most, being able to monitor their progress and come up with an additional plan of action. However, these results differ from Nunes’ (2004) findings since her students’ reflection revealed a different level of complexity from a more elementary level of thought to a higher level of metacognition, but they are broadly consistent with another of her findings regarding pre-service teachers’ reflections focused on the students’ learning styles, needs, and difficulties.

Challenges of Writing Portfolio Keeping With Pre-Service Teachers

As Dellet, Barnhardt, and Kevorkian (2001) and Aydin (2010b) claimed in their studies, portfolios are used due to teachers’ intentions to actively involve students in their learning process. Results from this study match those observed by these previous studies regarding students’ needs. Learners identified it as a challenge in the portfolio planning phase, highlighting that writing texts should be related to their own interests to promote both engagement and meaning. Nunes (2004) found similar results in her students’ reflection process.

Besides, the findings of the current study are consistent with those of Lam (2013), Barret (2000), and Aydin (2010a) who reported that EFL learners do not seem to be convinced by the contribution of peer feedback as a strategy to develop writing. However, an overall positive appraisal on peer feedback was elicited from pre-service teachers; they reported not possessing the necessary skills and practice to give feedback properly. This finding has implications in redefining the portfolio process with first year teachers’ trainees; either excluding peer feedback in the first levels of proficiency or explicitly training them to do a satisfactory task.

Peer feedback practice can help “to examine student feedback experiences in classrooms particularly in a pre-service context”, as pointed out by Gan, Nang, and Mu (2018, p. 506). On a final note, we agreed with Zhao (2010) who outlined a critical role of peer feedback as being “that ESL/EFL learners could potentially facilitate the development of their peers’ ESL/EFL proficiency” (p. 4), which is the role they will fulfil in the future. An important aspect of the portfolio strategy is giving and receiving feedback; it is especially significant since these learners will become teachers. Overall, the findings observed in this study mirror those of the previous studies that have examined the perception towards the contribution of EFL writing portfolios.

Conclusions and Implications

Since the EFL writing portfolio is perceived as an effective learning strategy to improve writing skills by pre-service teachers in an IELTE programme, researchers do believe this strategy has to be implemented along the programme. Besides, the study has shown that keeping the writing portfolio enhances the learning of vocabulary, grammar knowledge, text organisation and composition, teacher feedback, and reflection.

Additionally, pre-service teachers highly appraise constant teacher feedback and consider that it has an effect on their skills to revise and correct their errors in writing. Regarding peer feedback, it is a challenge for pre-service teachers; they value the strategy but do feel they need much more training and experience. From this point of view, students’ needs should be at the core of planning the strategy in order to fulfil their needs and engage them in active and meaningful learning.

This study has proved to be effective for pre-service teachers of the university where it was conducted, however this study only focuses on a single context with pre-service teachers; it is also necessary to include teacher educators’ perceptions and beliefs both in the implementation and development of the writing portfolio as a tool for learning and teaching. As to limitations, this study should include more varied sources of information through time, not only one snapshot of the reality as the study did with the questionnaires and focus group.