Introduction

Despite the advances in the educational field in terms of better coverage, inclusive classrooms, and standardization of processes, there is still an unbalance in the teaching-learning process in English language teaching (Castañeda-Trujillo, 2018) and in schools in general (Guerrero-Nieto & Quintero-Polo, 2016). It means that teachers usually have the main role in the classroom and they become the sole owners of knowledge and the ones who decide how and when this knowledge must be transmitted to their students. In this way, students tend to be seen as passive receivers of knowledge, with no agency over what they need to learn. They are like tabula rasa that must be filled (Freire, 1970/2007), and they seem to be given few opportunities to express themselves, neglecting the knowledge, beliefs, and opinions which they bring to the classroom and which are valuable for the process of learning a foreign language.

This study aims at analyzing how seventh graders represent their social context after working with and interpreting some songs in English with certain social contents in an English as a foreign language (EFL) class. From our experience as pre-service English language teachers in the teaching practicum, working with seventh graders at a public school in Bogotá, we could evidence the low participation of students in the English language classes. This fact is paradoxical since in a language class interaction and communication among all the participants are of paramount importance. Moreover, this interaction should promote language learning and foster language use (Lucero & Scalante-Morales, 2018). In the classes we observed, students commonly limited their participation to answering specific questions about grammar and vocabulary such as the literal meaning of words in Spanish (church = iglesia) or choosing the best auxiliary, subject, or verb according to short sentences. In the same way, teachers tend just to give instructions about the activities to be done during the class, acting in this way as passive technicians who assume others’ methodologies and strategies to approach English teaching (Kumaravadivelu, 2003). By doing this, teachers set aside the human aspect and how students feel during the learning process.

Therefore, it is necessary to start seeing students as

human beings who have the right of being heard and taken into account in the teaching process, and also to see themselves as cognitive subjects, able to read and assume contexts and able to seek opportunities for transformation through education. (Castañeda-Trujillo & Aguirre-Hernández, 2018, p. 169)

Thus, we propose to use a critical pedagogy (CP) perspective because it allows students to change their passive roles and become agents of their own learning (Shor, 1993). As music creates a pleasant atmosphere, which influences people in different positive ways, we want to link CP to the use of music as a means of reflection in the English classes (Rosová, 2007). Thence, we created a proposal for using music in an English class to encourage students to be reflective and active participants in the class (Palacios & Chapetón, 2014). Furthermore, we are not forgetting the teachers’ role, since this research could give them a useful perspective to take into account the social reality of the students and to transcend the classroom environment.

Theoretical Framework

Since this research intends to rescue the EFL students’ self-representations by means of a strategy based on CP through the use of songs in English, it is necessary to clarify how all these aspects relate to and connect each other throughout this research paper.

Context Representation Using Critical Pedagogy

First of all, we will explain how the concept of context representation is understood. Freire (1970/2007) states that context representation changes according to the moment and some circumstances.

[Students] will tend to reflect on their own “situationality” to the extent that they are challenged by it to act upon it. Human beings are because they are in a situation. And they will be more the more they not only critically reflect upon their existence but critically act upon it. (p. 109)

Similarly, McLaren and Giroux (1990) refer to context representation through an expression of CP, focusing on the importance people should give to tell their own stories and how they individually see the environment surrounding them in a multicultural and global society. Gruenewald (2003) mentions that students’ context representation is related to the kind of educative experiences they perceive in their partners and teachers, noticing the characteristics of the places in which they live and share with others, including family interaction at home. Likewise, as stated by Dehler, Welsh, and Lewis (2001), CP contributes to “students becom[ing] capable of a complicated understanding of the historical, social, political, and philosophical traditions underlying contemporary conceptions of organizations and management” (p. 493), that are maintained in their contemporary experiences and persist in the future.

Based on what Freire (1970/2007), McLaren and Giroux (1990), Gruenewald (2003), and Dehler et al. (2001) mentioned, we can say that context representations appear as a mixture of the immediate situations a person is living day by day, as familiar, academic, and professional surroundings. Then, the important thing is to link reflection through CP and act to change the context to make it favorable, understanding historical and current events. In the present study, reflection is promoted by asking students some questions about themselves, and as a result we were able to notice the immediate environment in which they are involved in and how they see the world in general. In that way, students acquired an awareness of the situations they were facing, and they could propose some solutions for those. Thus, we could observe how students appropriated their own realities and knowledge and expressed themselves freely to the whole class.

Songs in the EFL Classroom

Songs have been used as a resource in English classes to provide a relaxed and comfortable atmosphere, with the purpose of motivating students to be more receptive and participative during each class. Additionally, songs tend to describe experiences, feelings, and these can tell stories (Griffee, 1995). As Jolly (1975) expressed, songs are a great material or tool, because music makes them enjoyable and motivational and they favor the communicative component of language.

Furthermore, as Palacios and Chapetón (2014) state, songs bring to people’s minds different memories, which become more meaningful for students when those are used in a classroom. This recalling of memories happens because songs are usually written from personal experiences that happen in determined socio-cultural environments. Therefore, using songs in an EFL classroom could foster students’ participation in a more enjoyable environment (Phillips, 2003).

Taking the abovementioned into consideration, we used some songs with a social content. Then, we expected students to become more confident while communicating their thoughts and feelings in the foreign language, as well as experiencing an improvement in their interactive skills: listening and speaking. Besides this, using music in the classroom promotes students’ comfort and empathy about several topics, as well as helps them get close to the language and to their own lives inside or outside the classroom, as Palacios and Chapetón (2014) noticed in their research. These authors stated that the innovative use of songs fosters students’ reflection, and consequently, a more active and freer participation in the class.

Method

The purpose of this study is to analyze a group of students’ self-representations by connecting their own reality to the content of some songs in English used in a specific EFL class. To fulfil this purpose, we decided to use case study as the main research methodology, since this research method focuses on particularity (students’ self-representations of their realities), contextualization (English language classes in seventh grade in a public school), and interpretation (researchers analyzing the phenomenon) (Duff, 2008). The integration of these three components constitutes a “contemporary phenomenon within some real-life context” (Yin, 2003, p. 1). Furthermore, to analyze such self-representations of students’ realities, researchers just need to have “little control over events” during classes, activate students’ memory to evocate significant moments in their lives, and observe what happens within the classroom while the strategy is on (Gomm, Hammersley, & Foster, 2000; Yin, 2003, p. 1). As the scope of this research was to present a description of what happened within the context of students from their representations, this study is a descriptive case study (Duff, 2008).

We collected the data through students’ artifacts (drawings and short writings), classroom observations, closed-ended questionnaires, and dialogues with the students; all of these techniques and instruments served the purpose of getting information about their families, partners, and their relationships with teachers, and so on. During the process, other scenarios for sharing information emerged, so we could have spontaneous chats with students; these scenarios were more relaxed and for that reason, the information we got from them was very significant for our study. During the intervention, we assumed differentiated roles; one was that of the teacher (in charge of directing all the activities in the class), while the other was in charge of observing and collecting the most information possible. These two roles permitted us to interact in a closer way with the students and at the same time, analyze students’ outcomes deeply, influencing as little as possible students’ responses (Merriam, 1998).

The study was developed at a public school in Bogota, located in the downtown area of the city. This institution1 let us work as pre-service teachers in the English class with one grade, one day of the week. Therefore, our participants were eight seventh-grade students whose participation was voluntary and with prior permission from their parents or guardians. The participants were students ranging in age from 11 to 13 years old, who were experiencing a stage of changes in their lives during the intervention, the adolescence stage. At this age, students are still building their own identity; for them, all their experiences (positive or negative) become meaningful and relevant, even those experiences that an adult might consider as insignificant and irrelevant (Jackson & Goossens, 2006). They were in a constant struggle to know who they were in the path of becoming young and future adults, a struggle which could provoke not being understood by the world around them (Jackson & Goossens, 2006).

We used three different songs in the pedagogical design of this study. We selected these songs after applying a closed-ended questionnaire to students where they wrote about their musical likes. The results of this questionnaire let us select which artists could be interesting to our population. Then, we selected some songs that help our students explore their own contexts to express themselves later in the activities designed.

The first song that we used was Monster by Imagine Dragons. This song is about a person with a complicated past and how it is affecting his self-image. Based on this song, students wrote short texts about their self-image and how they feel with people around them. The second song was In My Blood by Shawn Mendes; it is about how sometimes the problems can overtake a person and how this person searches for solutions. Finally, the last song used was by Count on me by Bruno Mars, in which it is mentioned that we can count on someone to help us (a friend, a family member, a partner); also, this song is related to feelings of happiness. We analyzed students’ context representation by working on those aspects with them; they are better explained in the findings.

Our intention was to understand how students show their realities based on the songs’ topics worked during the English classes, and to observe the different representations that students created based on real-life issues by designing activities in which learners use the first and the foreign language to achieve a real outcome (Willis, 1996). Then, we worked with each song as follows: First, students listened to the song and understood the singer’s message, and second, students connected the songs’ contents with their lives in order to express themselves (written or orally). Regarding the data collected, these students’ artifacts let us gather meaningful information related to their experiences and feelings in order to study how each student represented her or himself. Moreover, we also used an observation technique in order to consign important aspects that happened in our classes for future analysis; these observations did not follow a specific rubric, however some aspects that we took into account were students’ attitudes at the moment of talking about their lives, English use, and students’ comments and reflections.

Findings

After listening to the songs selected, students worked on the activities designed by the teacher, so they did some drawings, posters, short conversations, and short written sentences, among others. Through these artifacts and the other data collection instruments, a series of representations linked to students’ closest context emerged. Likewise, the analysis of what the songs represented to students after using and discussing the lyrics of the songs is described in the following categories.

Feelings of Loneliness

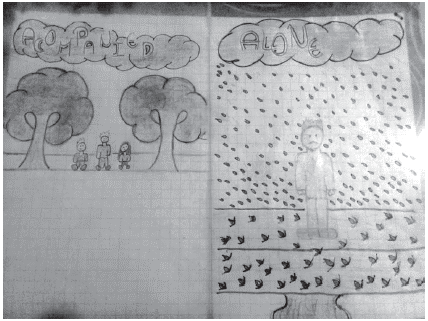

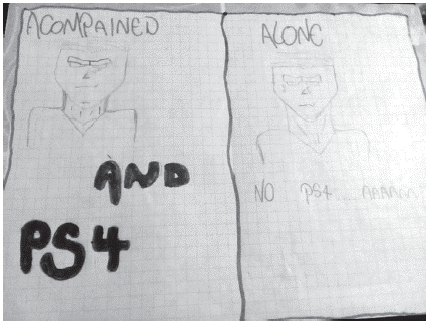

This category emerged when we found that the students’ answers and artefacts recurrently touched on the topic of feeling lonely. In one class, after listening to the song In My Blood and understanding the lyrics, some students expressed that they had felt alone, just as the main character of the song feels. Consequently, the students were asked to make a drawing in which they showed how they felt when they were alone and accompanied; throughout the analysis we noticed that the students perceived solitude as the absence of a relative (father, mother, siblings, friends, etc.) (Figure 1); also, some students even associated solitude with the absence of an object, as evidenced in Figure 2.

In the next class, we continued working with the song In My Blood. This song has a strong message about being alone, and that we sometimes need somebody else. After doing the exercises oriented to understanding the song, a spontaneous conversation with the students took place. This conversation started in English, however, the lack of proficiency they had did not permit the use of the proper language to express what they wanted to say. For that reason, we allowed them to use their mother tongue in this stage. After talking about some problems that affect them, we noticed a repetitive feeling in students’ answers: solitude. Therefore, we wanted to explore this feeling deeper. Then, we asked the students if they felt alone, when they feel alone, and what they do when that occurs. They expressed themselves as follows:

Yo me siento sola cuando estoy en mi casa y mi mamá no viene rápido (I feel alone when I am at home and my mother does not come fast). (Oral conversation, Laura)

Yo voy a mi casa y me siento peor…porque uno se siente sólo, no hay nadie que lo acompañe, uno lo que hace es dormir y ya…porque no está mi papá, entonces le toca hacer a uno todo solo (I go to my house and I feel worse…because I feel alone, there is nobody to accompany me, I only sleep…because my father is not there, so I have to do everything by myself). (Oral conversation, David)

A mí no me gusta llegar a la casa porque no hay nadie (I do not like to arrive home because there is nobody). (Oral conversation, Karla)

Cuando llego a la casa estoy solo, aburrido, no tengo con quien hablar (When I arrive home I am alone, bored, I do not have someone to talk with). (Oral conversation, Jhon)

The previous utterances denote a pattern of repetition, linking being at home to feeling alone because the students recognize they do not find anything to do or anyone to talk with. In addition to what they said before, we evidenced other similar opinions about a dislike of being in their houses; they would rather be at school because there they can interact with people similar to them. In addition, they find classmates who understand them, different from what happens at their homes, as evident below:

Yo prefiero quedarme en el colegio estudiando que...que estar lavando los platos a mi papá (I prefer to be studying in the school that… that being doing dishes to my father). (Oral conversation, John)

Yo a veces me siento solo en mi casa pues, aparte de que no hay nadie, nadie me entiende (I feel alone in my house sometimes, well, there is nobody and nobody understands me). (Oral conversation, David)

Sí, es que en el colegio al menos uno tiene a alguien con quien estar acompañado (Yes, in the school at least you have someone to be accompanied by). (Oral conversation, Laura)

In contrast to their opinions, only one student expressed:

Cuando yo estoy en la calle no me siento bien, me siento como que este no es mi lugar, uno llega a la casa y se siente mejor, como más seguro (When I am in the street i do not feel good, I feel like this is not my place, I arrive at home and I feel better, like safer). (Oral conversation, Brandon)

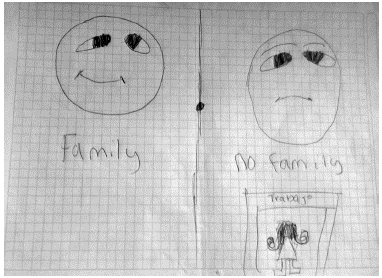

Also indicated is how society influences the behavior of students’ parents, being a consequence of the accelerated rhythm of lives in which people live nowadays, then most of the parents have to work long hours per day in order to obtain a minimum salary. Children associate this event with solitude (Figure 3), resulting in students only having an “approximation” with their parents when they return home at night as one student mentions, or they find themselves not spending quality time ”en famille”.

Yo me he sentido sola porque no tengo una persona a quien contarle mis cosas porque con mi hermana no tengo a veces tanta relación y pues mi mamá trabaja todo el día así que la veo a veces por la noche (I have felt alone because I do not have a person to talk about my things, because with my sister sometimes I do not have much relation and my mother works all day, so I see her sometimes at night). (Written representation of solitude, Laura)

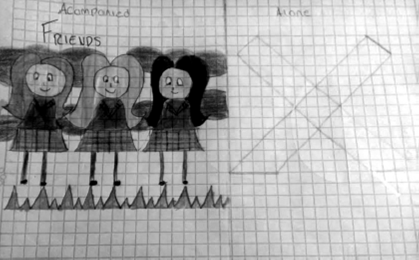

In the same class, we identified, from students’ spoken opinions, that adults commonly ignore the situations children have to face at school or at home. Additionally, parents do not give a place to important events for the children due to the lack of time for interaction between them. This lack of attention generates students’ looking for different alternatives in order to avoid loneliness (Figure 4). Then, most of the time the students prefer the use of electronic devices, social media, or video games; something that does not solve the problem in the long term because they begin to develop a feeling of dependency on those devices as one of the students expressed:

Me sentí demasiado solo cuando me quitaron mis teléfonos (I felt so alone when they took my telephones away.). (Oral conversation, David)

It is also important to highlight that some of the students did not show any relation to solitude feeling; they put an “X” rather than making a drawing in the “Alone” section (Figure 5), or they expressed the following:

Yo nunca me he sentido sola (I have never felt alone). (Oral conversation, Sara)

Profe, no tengo nada que dibujar, yo no me he sentido sola (Teacher, I have nothing to draw, I have never felt alone). (Oral conversation, Gabriella)

While interpreting students’ representations, we realized that solitude is not the only aspect they expressed. There is another element that deserved attention, as it is also an important part of students’ immediate environment: physical and verbal mistreatment.

Physical and Verbal Mistreatment

Throughout the pedagogical intervention, the students continued representing their realities based on the songs In My Blood and Monster, since those songs focus on the idea of feeling alone and different from the rest of people, feelings that result very familiar for the majority of adolescents. Students described how they have felt mistreated by their loved ones on some occasions, mainly by the use of verbal violence. Consequently, that mistreatment causes them a feeling of sadness that can be evidenced in their drawings (Figure 6). At the same time, this situation shows how tough the students’ family realities can be, since some of them do not have “traditional families” with a father or a mother. In fact, most of them do not live with their parents but live with another family member such as their grandparents, uncles or aunts, and even step parents.

“Tú eres el peor error que yo he conocido” [sic] (“You are the worst mistake that I have ever known”)

Likewise, another student talked about how sometimes his social situation affected him; because he belongs to a low stratum, he has suffered abuse by some people and we realized how he underestimated the way he feels when being treated like this.

Yo no me siento mal, o pues un poquito pues porque antes me trataban tan mal, decían que era muy pobre que no iba a poder pasar el año y ellos hacían cosas malas y me trataban mal (I do not feel bad, or well a little bit because before they used to treat me so bad, they said that I was very poor and that I would not be able to pass the year. They did bad things and treated me badly). (Short writing, David)

On the other hand, we also observed that the mistreatment that some students have suffered is not only inflicted by their relatives but also by their classmates. As in the following example, a student commented on a situation that happened with his classmates. This revealed how the situation made him feel rejected, having negative effects when students have to work in groups because they tend to reject each other; besides, situations like this can explain why some students feel comfortable in the school, but others isolate themselves and avoid talking to others about what they live.

Me siento solo cuando todos me abuchean…ay yo no sé, yo llego tarde y todos empiezan ah naa salgase…me tienen aburrido…yo me siento re feo (I feel lonely when everybody boos me…oh I do not know, I am late and they all start ah no get out…they have me bored…I feel very bad). (Oral conversation, David)

Regarding the physical abuse, the students did not talk much about it. However, there was a student who mentioned a case in which one of her classmates was mistreated by her father. Thus, this shows how students also represent the reality of others.

Yo tenía una compañera que...o sea…o sea hablaba mucho con la profesora, pero la profesora le daba mucho respaldo porque ella no tenía mucho apoyo ni de la mamá ni del papá, porque el papá siempre le pegaba y eso, por cualquier cosa, era maltratada re feo (I had a partner that…I mean…I mean she talked a lot with the teacher, but the teacher gave her backing because she did not have much support either from her mother or from her father, because her father always hit her and things like that, for anything, she was mistreated so ugly). (Oral conversation, Sara)

Even with the applied activities, some students did not feel comfortable talking about certain topics, making us think about the different ways in which they confront and manage their troubles. Consequently, we decided to work on this issue with the students in order to understand them better.

Problems Management

After having analyzed some concerns expressed by the students, we turned our attention to problems management. Thus, we have learned how the students looked for solutions to their problems, what they proposed to do and how they dealt with them. For that reason, we based our classroom discussion on the song In My Blood specifically on the part that mentions how people should not give up despite having many problems. Then, we decided to focus on solving problems of loneliness since it was the issue worked with the students, to which they proposed being with friends or the family, listening to music, writing, and seeking refuge on TV or social media. In contrast, other students prefer to be alone when they have a problem or feel bad:

Cuando me siento sola o triste escribo cosas en un cuaderno que me sienta bien, o miro televisión o hablo con mis amigos, familiares (When I am feeling alone or sad I write things in a notebook that makes me feel good or watch TV). (Solutions to loneliness, Laura)

Cuando estoy triste no me gusta que me molesten y escucho música (When I am sad I do not like being disturbed and I listen to music). (Short writing about solutions to loneliness, Alex)

Continuing with this category and having some dialogues with students, we noticed again how they prefer talking with their classmates at school than talking about their problems at home. Therefore, we can understand how important the school is for the students as we mentioned before, since there, apart from being their place to socialize, it is a place that allows them to surround themselves with people that make them feel more confident and comfortable. We can illustrate the above with the following example:

Profesora: Cuando ustedes sienten que tienen problemas, ¿se sienten mejor hablándolo en el colegio o hablando en sus casas?

Estudiante: Pues yo me siento mejor aquí hablando en el colegio porque en la casa nadie lo comprende, en cambio aquí uno puede conocer gente de la misma edad de uno o mayor y hablar de lo que uno tiene.

Teacher: When you feel you have problems, do you feel better talking about it at school or talking at home?

Student: Well, I feel better here, talking at school because no one in the house understands me, but here you can meet people of the same age as one or older and talk about what you have. (Dialogues between students and teacher)

However, other students mentioned how they solve their own problems without requiring the help of others. They found out a way to cope with such difficulties by facing them instead of escaping from them.

Profesora: ¿Ustedes expresan los problemas a sus profesores?

Estudiante: Cuando yo tengo un problema no le cuento a nadie.

Profesora: ¿A nadie?

Estudiante: No, yo me pongo a pensar en cómo solucionarlo.

Teacher: Do you express your problems to your teachers?

Student: When I have a problem, I do not tell anyone.

Teacher: To anyone?

Student: No, I set about thinking how to solve it. (Dialogues between students and teachers)

Al estar ahí escuchando la canción (Monster) me acuerda a lo que siempre hago, dejar y olvidar todo atrás (Being there listening to the song (Monster) reminds me of what I always do, leave and forget everything behind). (Short writing, Alex)

I feel identified by the chorus, I want to escape the problems and be free, I did bad things and I want to fix it, I don’t want problems. [sic] (Short writing, Brandon)

The categories so far have shown some aspects that are not that positive about students’ context. The last one, on the contrary, highlights positive representations from what students have lived.

Moments of Happiness

During the last class, we proposed the creation of a letter in which students could describe the best day of their lives to a close person they trust and count on, after listening to the last song Count on me. This song is about having someone that supports you in your difficulties. Hence, in this section we found two subcategories: Happiness associated exclusively with people, and Happiness associated with people, objects, and places at the same time.

Happiness associated exclusively with people. In the case of some students, we distinguish that happiness for them is present in little things as spending a whole day with each one’s family, laughing with them, and realizing how fortunate they are. In this way, to talk and feel listened to by someone is something students appreciate and give a big value to; additionally, happiness for them has to do with self-esteem and accepting themselves as they are. We can evidence it thought the next letters students wrote:

Que vivo con mi familia y no me falta nada y tengo a mi madrecita viva y con ella disfruto lo positivo en mi vida. Que tengo todo y soy feliz así como soy (I live with my family and do not lack anything. I have my mom alive and I enjoy with her the positive things in my life. I have everything, and I am happy as I am). (Letter written by Gabriella)

The students demonstrated a feeling of gratitude with their relatives and friends just for being accompanied by them at any moment, regardless if such moments are good or bad. They described how they feel secure, helped, supported, and loved sharing with someone else and emphasizing on the special aspects they discover in others.

Gracias Lely, me siento segura siempre en lo buenos momentos; a pesar de que peleamos, nosotras estamos en lo bueno y en lo malo. Mis mejores momentos son contigo en cada momento (Thanks Lely, I always feel safe in good moments; although we fight, we are together in good and bad times. My best moments are with you every time). (Letter written by Sara)

Happiness associated with people, objects, and places at the same time. Most of the students related those three aspects as a mixture to express happiness. They chose for consideration the celebration of special dates or holidays like birthdays, Christmas, and Halloween, in which they have a close interaction with their families, going to see/visit new exciting places, taking a trip, and receiving some gifts. They expressed a correlation between being with all their families and feeling union and affection:

My day more happy is my brtday number 13 why was a the festival of horror the Salitre Mágico. Too eat pastel and I receive much gift for my family. [sic] (Letter in English written by John)

Moreover, they related happiness to the act of their meeting new people at school or in the neighborhood. That way, they share with people of their same age, establishing interpersonal relationships, which make up their personality from childhood to adulthood as we identify below:

My best moment was to meet to my best friend and went with her to the amusement park. [sic] (Letter in English written by Isabella)

It is important to add that through the classes we could notice some students did not have enough resources to eat well every day. For instance, one student kept his snacks for his sister’s lunch every day because it was difficult for his family to provide a daily meal for them both. In this sense, social strata or life conditions also intervene in the feeling of happiness. One student expressed happiness as receiving food from someone; we made an approximation and asked him directly what he was trying to say exactly and he answered:

Es la única vez que alguien me ha dado un postre en mi vida, lo disfruté, por eso es el mejor día de mi vida (It is the only time that someone has given me a dessert in my life, I enjoyed it, for that reason it is the best day of my life). (Informal conversation, David)

In other cases, some students represented happiness as contact with living beings as pets, which is a way to notice they may respect and live together with nature and animals, as well live without hurting them. On the other hand, some students expressed happiness towards an object or by talking to the teachers like this:

El mejor día fue cuando me dieron mi celular (The best day was when they gave me my cell phone). (Informal conversation, Brandon)

My best day was when I touched a soccer ball. [sic] (Letter in English written by Brandon)

Mommy my happiest day is when they gave me my kitten, I felt so happy just the…[sic] (Letter in English written by Karla)

As a piece of evidence that not all the students think the same, only one of the students declared that he has never had a “best” day in his life, he stressed in that idea, but also mentioning that he trusts his family and friends:

I trust on my family and mine best friends. Besta day…no I have. What no I have!!! [sic] (Letter in English written by David)

Finally, we can close this category by saying that students do not need so many things to feel happy. They just need to feel accompanied, understood, having any member of their family who trusts them and support them to achieve their dreams as expressed below:

My mother beautiful. Mommy my happiest day it was when you took me to the cinema to watch Intensely and we laughed together. We spent nice time, we ate and we had fun too. Looked so beautiful, you look beautiful all day but that day was the best of my day. [sic] (Letter in English written by Karla)

Discussion

The findings demonstrate how designing activities from a CP perspective can be beneficial for EFL classes, since it allows students to take an active and dynamic role in the classroom. For instance, the students increased their interventions throughout the classes, something that promotes meaningful learning because they used their own knowledge to interact with others using the target language for talking about their realities. Therefore, this type of experience allows them to understand their environment and to appropriate their learning, making them freer and more conscientious learners (Shor, 1993), increasing their confidence and, equally, their participation in class.

In the same way, students became more open to talk about their contexts, identifying themselves and recognizing themselves in others. Even though there were similar realities in the students’ stories which they felt reflected themselves, they also learned to accept the different life experiences of others. Thus, we realize the importance of each student telling their stories, highlighting their individuality, and demonstrating the diverse contexts representations (McLaren & Giroux, 1990).

Moreover, we want to mention the importance that experiences play in students’ lives, especially during adolescence. “Adolescents experience greater emotional variability than other age groups” (Jackson & Goossens, 2006); they really feel and act as they feel. For that reason, adolescents might face drastic emotional changes, and the perception of their context will depend on their mood. The previous is a call to pay attention to what students express with or without words inside the classroom. Teachers might be able to understand these kinds of messages students send, since they are in charge not only of providing the content knowledge, but of guaranteeing a more integral education.

Apart from the aspects discussed before, we consider education should not be a technical process, but rather a critical space open to curiosity (Shor, 1993) where students and teachers interact reciprocally and share experiences to create a conscientious environment. Teachers need to remember they share that space with human beings and for that reason it is important to listen to students because although they are often underestimated, they have many things to contribute in the classroom dynamics.

Nevertheless, we experienced some limitations in our study. First, our limited population, since there were only eight students giving more specific results. Second, as pre-service teachers, we had a time restriction for working with the students, owing to the school’s having a stipulated curriculum, which we had to articulate with our research, diminishing time for data collection. As a result, we could not measure whether there was a deep change or stability in the students’ answers by applying the intervention for a longer time. Lastly, as we held some open dialogues with all the students at the same time, everybody wanted to give their opinion and they did not respect the speaking turn of the others, which made it difficult to delve deeper into their answers.

To the future researchers, we recommend choosing a dialogic interview as one of the instruments for gathering data, as it permits being closer to the students. This kind of dialogue also allows students to open up more and go deeper into their thoughts and feelings.

Conclusions

The study showed that the adolescent students’ representations were varied. Hence, the application of English songs helped us to encourage our students to explore and reflect on their contexts with topics closed to them. Besides, the use of a CP perspective while developing the class stimulated students to talk about their contexts, which revealed some concerns about their relationships with their family members and friends, allowing different issues about the social contexts in which they are involved to become known. Likewise, the students presented some alternatives for dealing with their worries. We centered our attention on listening to the students and learning what they had to say about their lives; as a result, we focused on four issues found in the students’ answers:

In the first place, the students expressed a feeling of loneliness, mainly in their houses. They associated this emotional state with the absence of a person (parents, siblings, or friends) or an object (cell phones, game consoles). Although they showed a desire for sharing with their families, most of them find refuge in technology. In the second place, some of them expressed being affected by verbal and physical abuse, both from their parents and classmates. This mistreatment represented by students allows us to interpret the difficult family conditions of the students since they are at home without the presence of a relative, which can become a negative factor for the students’ feelings.

As a third aspect, we also worked with the students about problems management. In this case, some of them, having an independent attitude, prefer to solve those problems by themselves; however, other students expressed a need of being heard and advised by their families. Finally, the last category focused on positive students’ representations of their contexts; students are able to find solutions to some of the problems they have to face daily, such as solitude, rejection, and mistreatment, among others, and they consider the school as the place where they can socialize and find people who share their likes and who can understand them.

In terms of students’ participation during the language classes, throughout this research the students showed an improvement in communication, having better self-confidence at the moment of expressing their opinions and even proposing activities to develop during the classes. In addition, language improvement was not one of the goals of this study, but indirectly language use increased notably; then, students were motivated to speak more in the target language (English) and the increased use reinforced the writing skill.

This study is also a wakeup call to students’ parents to devote more quality time to their kids, especially during the childhood stage when they need attention to become strong and need a guide to act correctly in society.