Introduction

English as a foreign language (EFL) is taught across the globe with the aim of encouraging students to become more socio-economically competitive and, ultimately, to achieve better academic success (Dang, Nguyen, & Le, 2013; Guo, 2012; Usma, 2009a; Wilkinson, 2015). Although research strongly suggests that the use of multiple languages support second language learning (C. Baker, 2001; Cummins, 1996, 2001; Hornberger, 1995, 2002), in Colombian classrooms the standard practice remains one of banning the use of languages other than English, including Indigenous languages (Miranda-Nieves, 2018; Peláez & Usma, 2017; Usma, 2009a, 2015; Usma & Peláez, 2017), and many teachers and policymakers still believe that in order to learn English effectively, students must use English exclusively.

In this article, I will employ plurilingualism and translanguaging as concepts to argue for the validation and recognition of students’ native language (which in this case is Spanish or may be an Indigenous language), as well as their personal backgrounds and identities. I will present a classroom scenario in which students are encouraged to use their first language to make meaning as they learn English. Here, the teacher promotes the use of Spanish during the learning of English in order to consolidate the teaching of English, while using social-justice themes collaboratively. These classroom experiences exemplify how literacy and the validation of first languages can successfully be implemented as ways to remove barriers to learning. It also showcases how, by allowing students to engage in their first language, serious issues regarding social interactions (such as bullying and aggression) can be discussed in the class, while simultaneously and effectively achieving English literacy skills. Further, using these English-classroom experiences as examples, I propose that plurilingualism and translanguaging converge in the classroom as an approach to teaching; which I refer to in Spanish as trans[cultura]linguación (i.e., the synergy of languages interacting with cultures in a pedagogical task). In this process, students use their knowledge of Spanish and English to make meaning as they experience the merging cultures or subcultures. Although I will focus here on non-English speaking countries in Latin America (specifically Colombia), this approach can also be applied to other international contexts.

Finally, I advocate for a paradigm shift in teacher education programs and language research in which plurilingualism and translanguaging are adopted as approaches to EFL learning in contexts where English is not the official language of instruction. I argue that these approaches provide an equitable avenue for all students to successfully learn English, regardless of their socioeconomic status. I ultimately posit that this paradigm shift in EFL pedagogies may foster an inclusive learning environment in which students make meaning while collaborating with and supporting each other.

Conceptual Considerations

This article is framed within two main concepts that co-habit and are juxtaposed concomitantly. First, plurilingualism as a concept values and acknowledges the cultural and linguistic backgrounds that students bring to the classroom. Second, translanguaging is an approach that allows students to use their first language to make meaning in specific pedagogical learning tasks.

Plurilingualism

First of all, it is important to highlight that the idea of using languages for the purpose of meaning making is not a new concept since Indigenous communities around the world have been doing it for millennia. Certain Indigenous communities in the Americas, Australia, central Asia, and Africa have always been using and mixing different languages as a symbolic behaviour that have allowed them to communicate for the purposes of trade, self-determination, human connection and cultural identity affirmation (Henderson & Nash, 1997; Hornberger, 2009; Skutnabb-Kangas, 2012; United Nations, 2012, 2016; Walsh & Yallop, 1993). However, in broad terms, plurilingualism refers to the number of languages or even variations of the same languages that coexist in the same society (Council of Europe, 2001). The concept behind plurilingualism implies that the languages we use for communication are not siloed or homogenous monolithic systems, but are elements of a dynamic multi-system that overlaps with other languages (Wandruszka as cited in Piccardo, 2013).

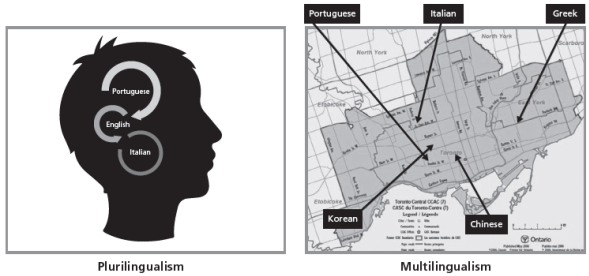

Whether located in North America or Europe, multilingualism and plurilingualism are sometimes interchangeable and can be confusing (Galante, 2018). For the purposes of this article, I would like to make a subtle distinction. For example, some scholars recognize multilingualism as languages interacting at a societal level (Toronto, New York, or London are examples of today’s multilingual cities), whereas plurilingualism looks at the languages that an individual possesses at any given time in life (Cavalli, Coste, Crişan, & van de Ven, 2009). In other words, a person who speaks or knows various languages or variations of the same language is a plurilingual person, and a city in which there are many languages and cultures interacting is considered a multicultural city (see Figure 1). A good example of a plurilingual individual would be someone who was born in Brazil, then travelled to Ecuador, where he learned Spanish, and later visited the USA for educational purposes, and then subsequently married an Italian woman. In addition to having acquired at least four languages-to various degrees of fluency-this person also has some knowledge of the Indigenous languages that his grandparents used to speak. Some may claim that since most of the people on the planet know more than one language or variations of the same languages (including Indigenous languages), we can say that we are all, in some degree, plurilingual (Piccardo, 2013).

Plurilingualism does not work in isolation; it works in tandem with both concepts of plurilingual and pluricultural competence, recognizing the ability a person has to use various languages in a communicative intercultural interaction. This person is seen as a social agent who has various degrees of linguistic proficiency and who has experiences across several cultures (Council of Europe, 2001). One of the highlights of plurilingualism is that it has assumed a subtle yet profound shift in perspective towards the use of multiple languages, in a manner that benefits individuals by negating the notion that it is essential to achieve linguistic perfection; this removes the stress of trying to achieve the fluency of a native speaker (Coste, Moore, & Zarate, 2009).

Further, plurilingual and pluricultural concepts can become the point of departure for equitable education, especially in the area of language teaching. Piccardo (2013) offers a synergic vision that proposes a change from a monolingual paradigm of language teaching to a plurilingual one; this allows for a pedagogy whose goal is to move away from the hierarchies of languages. Piccardo proposes key principles that can be applicable to any classrooms or language policies:

The teaching and learning of languages should strive for promoting languages and linguistic diversity,

Cross-curricular approaches in which languages interact synergistically should be fostered;

Transferable language skills should be cost-efficient, leading to awareness and self-esteem in learners that potentially optimize learning.

These principles validate and empower students and their cultures, making language-learning more relevant to their lived experiences, and consequently more equitable. Thus, it makes sense that a plurilingual approach to education can encourage a more robust socially just pedagogy. For Piccardo (2013, 2016) shifting towards a plurilingual approach to language education constitutes a pivotal social-justice issue, because it minimizes the barrier between languages and their different varieties, making education more holistic, synergic, and inclusive. She posits that “once such a conceptual shift towards plurality occurs, the door is open for people not only to accept plurilingualism but to take pride in it and to capitalize on it” (Piccardo, 2016, p. 12). In other words, a plurilingual approach-one in which students’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds are being asserted-provides a means to reduce their fear of language production.

Translanguaging

When a person has a document in English and writes the content in Spanish for a Spanish-language audience to understand it, that is translation (M. Baker, 1998). When two bilingual people are having an informal conversation and they switch languages as a strategy because they cannot find the phrase/word meaning in one of the languages, that is code-switching (Gumperz, 1982). If I read an article in English and then I discuss the content in Spanish with my peers, that is translanguaging (García & Wei, 2014). In order to understand what translanguaging encompasses, the concept of languaging needs to be clearly defined.

Languaging as a concept is not new; Maturana (1978) had already proposed the term lenguajear in Spanish; this refers to how language is incorporated in our lives as a mode of living and as a continuing and ever-changing process of our interactions with other human beings. Here, he helps us to understand languaging as an approach to express our thoughts, emotions, and feelings as processes to make meaning. In the field of language learning, the work of Swain (2008) on the conceptualization of languaging has been fundamental. For her, languaging means producing language in an attempt to understand and solve problems, as well as the process of making meaning in a specific language-learning situation. It conveys an action that is both dynamic and a never-ending process. In languaging, language is used to mediate cognition, or to act as a vehicle through which thinking is articulated and transformed into written or spoken form. Empirical data demonstrate how language students set about solving problems, using language as a tool to mediate their thinking, and thereby help and support each other in making meaning. For example, Tocalli-Beller (2005) highlights a lesson about idiomatic expressions in which students were able to support each other in order to understand given idiomatic expressions in an English class, and this exchange allowed students to reflect on their own learning, making them perform better on subsequent tasks.

García and Sylvan (2011) state: “Languaging is different from language conceived simply as a system of rules or structures; languaging is a product of social action and refers to discursive practices of people” (p. 389). In multilingual contexts, languaging transcends the barriers of meaning-making and becomes a process in which bilingual/multilingual teachers and students engage in complex discursive practices in order to “make sense” and communicate-this process is called “translanguaging”. This term was first coined by Cen Williams (as cited in Lewis, Jones, & Baker, 2012) for the systematic planning and use of two languages in the same lesson. Also, García (2009) and García and Wei (2014) describe translanguaging as the communicative norm of multilingual communities and the different discursive practices as seen from the speakers of these communities; they are not only a duality of separated languages but one linguistic repertoire that is used to make meaning. The authors also argue that translanguaging may include translation and code-switching practices, not necessarily as a shuttle between two languages, but as elaborated bilingual linguistic practices to make sense by doing various production and comprehension tasks.

One of the many advantages of translanguaging is that it facilitates finding a balance in the power relations among languages in the classroom. Canagarajah (2011) notes that multilingual language students feel free to use the languages with which they are more comfortable in using to make meaning, thus countering school impositions of monolinguistic ideologies. Consequently, the main advantage of a translanguage-infused classroom is that it inspires and transforms pedagogies that acknowledge the students’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds. C. Baker (2001) describes four main pedagogical advantages of translanguaging:

It promotes a better, deeper, and fuller understanding of the subject matter.

It helps students to strengthen their weaker language.

It supports students with home-school links and cooperation.

It integrates fluent learners with beginner students.

Furthermore, translanguaging explains the constant adaptation, movement, and fluidity of languages in contemporary multilingual societies. English language learners are constantly using their linguistic repertoires to make meaning. As a pedagogy, translanguaging allows flexibility in language teaching and takes away the stress that EFL teachers may experience when thinking rigidly about the exclusive use of English in the classroom. For all these reasons, I posit that translanguaging can be enacted in the classroom as a means of encouraging social justice. Kleyn (2016) underlies this notion when he argues that translanguaging is an equitable approach to education in which students’ linguistic and cultural resources are brought to class. Teacher-educators and teacher candidates must ask themselves what the sociopolitical and economic reasons are and why they are promoting English-only policies, and why racialized ideologies are given free rein to silence language practices which, otherwise, would allow the coexistence of other languages and their variations inside the English language classroom. To this end, Kleyn recommends a discussion of the following questions with students and future teachers:

Voice: What is the role of translanguaging in providing voice to emergent bilinguals? If students are denied the use of their home language, what are the implications educationally, emotionally, and politically?

Freedom: To what extent is linguistic freedom provided to students who speak a home language that differs from the national language? Are the human and linguistic rights of these students being met? If not, what changes need to occur at the national, local, and school levels?

Access: How is access to learning content and a new language facilitated or limited to emergent bilinguals, and why? And what role can translanguaging play in making learning more accessible?

Answering these questions will allow us to better comprehend the need to create a space to educate children equitably within a socially just environment. This will be a space in which students are encouraged to build on their translanguaging practices and discourses, as teachers build on those flexible practices in order to challenge the concept of the ideal “standard language” (García & Leiva, 2014) that many policies and classroom teachers have strived to achieve for so many years.

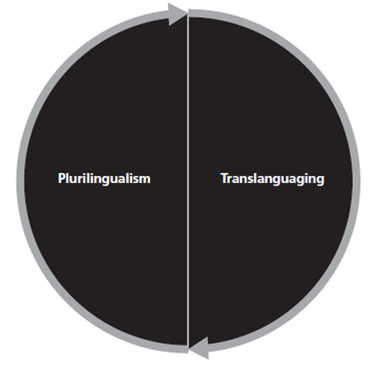

Finally, I have argued that plurilingualism and translanguaging as concepts support spaces that allow students to use their language repertoires. Nevertheless, this does not happen in a vacuum, but is created through the everyday practices of the speakers, which are sociohistorical in nature (Heller, 2007). These practices are not fixed or straightforward from the beliefs or attitudes of individuals who interact in multilingual contexts who have an array of lived experiences. Thus, this plurilingual and translanguaging ideological approach to language equips and empowers bilingual or multilingual speakers to challenge the monolingual dominant paradigm and to resist the tendency some researchers have to study languages as existing in isolated silos. Heller (2007) further asserts that this approach presents a more flexible idea of bilingualism and represents a view of envisioning languages as a societal resource, stressing the individuals’ agency and ability to perform in different social situations. Additionally, Creese and Blackledge (2011) suggest that “flexible bilingualism can be viewed as heteroglossia rather than code-switching, allowing the speaker rather than the language to be placed at the heart of the interaction, and linguistic practices to be situated in their social, political and historical conditions” (p. 1206). In other words, language and learning are no longer seen as separate entities, but rather as a process in which the speakers and their interaction become the sum of their experiences, their histories, and their lives.

Although it has been demonstrated that a monolingual EFL classroom may present power relations that can create conflict among students (Forero-Rocha & Gómez-Rodríguez, 2016), adopting a plurilingual and translanguaging approach to education may position the school as a site for transformation and production of social equality. This may be reflected in the way in which students and teachers work as mediators for problem-solving during the learning process, thereby fostering a more equitable learning environment. Ultimately, the concepts described in this section do not act in isolation but interact with each other much like a linguistic ecosystem (see Figure 2) in which language-learning is situated in very specific spaces, places, and times.

Classroom Experience: Teaching About/for Social Justice

In general, plurilingual pedagogies and translanguaging approaches to teaching EFL in Latin America have been minimally explored in the academic literature (Escobar-Fallas & Dillard-Paltrineri, 2015), and may not have been explored explicitly at all in Colombia. Here, I present a classroom experience in which a Colombian high school teacher uses a social-justice approach to teaching English by (a) discussing issues related to problematic situations in the school and (b) allowing students to use their linguistic repertoires to make meaning as they discussed these issues. In my relationship with the teacher I acted as a critical friend (Costa & Kallick, 1993) where my role was to understand the teacher’s concerns with regard to her class. I heard her teaching stories; I gave feedback and I offered emotional support whenever she felt it was needed.

With over 20 years of English teaching experience, Laura1 teaches EFL in a high school in the south of Bogota, Colombia. The neighbourhood in which she works is located in a poor area of the city where displaced people from the war,2 African Colombians and campesinos3 live. Most of her students have experienced violence at home, in school, and on the street, at the hands of parents, relatives, and street-gang members. Additionally, students do not have much exposure to English outside the school and do not have opportunities to practice English, thus making Laura’s teaching job more demanding. Despite this challenge, while reflecting on her work with her class, Laura expressed that her personal goal was to use her grade nine class as a space to foster a welcoming environment for learning English, as well as using English language learning as an opportunity to empower her students to become agents of social change.

The classroom experience presented in this article serves as an example of how Laura uses a dynamic plurilingual pedagogy as a dialogical action (García & Sylvan, 2011) to draw on the knowledge of students’ own culture and other “internal” cultures of Colombia to make connections between their Spanish-language repertoire (which includes knowledge of other variations of Spanish) and English. By using this approach, Laura’s unintentional expectation is to teach about social justice, so her class becomes one that works for social justice.

Laura’s experiences in high school enabled her to witness the inequalities that her students have faced over the years. Many students come to class having no breakfast, others have problems with their families, and some suffer bullying and victimization from local ruthless and violent groups. In many of our conversations, Laura would ask herself: “How can my English class address these issues? And how can I create a more peaceful learning environment in my classes?”

She teaches English for around three hours a week in a grade nine class; her students are in level A1 of the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) scale. According to Laura, since her students are not proficient enough in English, everyone uses Spanish for meaning-making. Most of the time, she writes on the board in English to explain a concept after which she would translate it into Spanish. As much as the students try hard to speak in English, they seem to struggle, so she continually asks herself how her class can be more engaging, meaningful, and motivating, so that her students are encouraged to use more English.

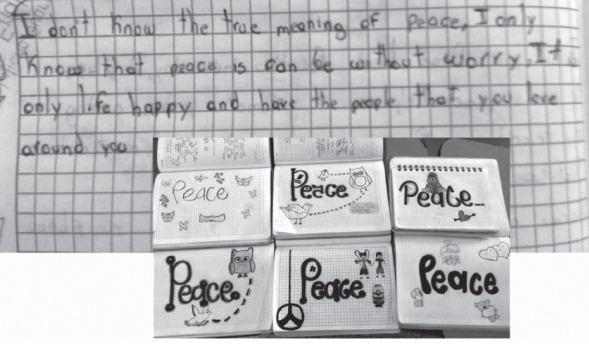

In order to address this issue, Laura thought that it was a sound idea to discuss social problems through the lens of peace education. Laura and her students collaboratively developed a social justice-oriented project. First, she asked her students what the meaning of peace was to them. Laura spent a few classes discussing the concept of peace, her students responded mainly in Spanish and Laura scaffolded some of the language they used into English. She realized that their answers were vague and unclear, so she encouraged them to expand their ideas by drawing and writing some sentences in English with her help (see Figure 3).

After a few weeks, Laura decided that merely drawing was not enough and that talking about peace needed a more active component. Students felt engaged with the first task and they then proposed to Laura to do skits to talk about peace. Laura suggested a more concrete action and motivated students to discuss and propose how they could prepare skits about how to stop school bullying. The students and the teacher used Spanish to discuss different types and characteristics of bullying. They discussed who the bullies, accomplices, bystanders, and victims were in their own context. After that, they had conversations about possible ways to prevent and respond to bullying. As a final activity to wrap up these discussions, students drafted skit scripts in Spanish, and Laura helped them to translate and edit them in English. After several weeks of language support and feedback provided by Laura and performative skills supervised by the drama teacher who helped students to rehearse and be ready for presentations, the final project was presented before the class, and a few weeks later, before the entire school in the form of a drama performance.

Laura argues that this project could not have been possible if she had not allowed the students to use Spanish to carry out the activities. Her students expressed the view that the whole project was easier to carry out because of that and asserted that they had learned more English than before. They indeed felt more empowered and motivated to learn more English after that experience. Laura confirmed that this group continued using Spanish to scaffold English-learning while simultaneously creating a campaign against bullying by using drama and other art forms such as painting, graffiti, dancing, and hip-hop.

Discussion: Trans[cultura]linguación

The concept of translanguaging (García & Wei, 2014) has been used as the communicative norm of multilingual communities in North America and sometimes elsewhere. For example, when used as a pedagogical strategy, Lewis et al. (2012) and García (2011) have proposed the use of languages alternatively for input and output activities in the English language classroom. This allows multilingual speakers to engage in discursive practices as a way of making sense of their bilingual worlds. Translanguaging has been demonstrated to be a powerful tool that can challenge monolingual and colonial tendencies of the English language by giving space for students to draw on their fluid linguistic and cultural resources (de los Ríos & Seltzer, 2017). For example, García and Sylvan (2011) described translanguaging as a dynamic plurilingual pedagogy in which students were allowed to use their home languages at an International High School in New York as a way of making sense of a learning moment. Similarly, Laura challenged the traditional approaches to teaching despite the unspoken Colombian linguistic-policy expectation to speak English during the entire time in class. By challenging static models of teaching and allowing dynamic approaches in the classroom, Laura’s class has become a good example of how to further social justice, and how to change power relations, promote equal access, and encourage the generation of knowledge (Goldfarb & Grinberg, 2002). Due to the ethnic and geographical diversity of the students in Laura’s class, she argues that it is important to respect all variations of Spanish and to allow students to use those variations to interact with each other during English activities.

Laura’s class exemplifies translanguaging practices in which languages are not only being used to make meaning, but also to learn about the students’ own culture. Laura tapped into her students’ Colombian cultural and linguistic capital in order to make meaning, build upon, and understand vocabulary in English. Students not only became more aware of the different variations of their own Colombian Spanish from various regions of the country, but were also able to make connections to the same phenomenon in English. In other words, Spanish has been used to learn English, and culture has been placed at the centre of learning to draw meanings.

In order to exemplify this, in one of Laura’s classes, while rehearsing the skits, she discussed how American English is different from that spoken in England, and she brought up an example from Colombian culture. The word bolsa (bag in Spanish) has different meanings in different regions of Colombia. Students were prompted to give examples of how they say the same word in the different cities from where they came. For example, for one student from El Valle (a province in Colombia) chuspa is the word for bag, whereas for another student from Cundinamarca (another province) talego is the word they use. She encouraged her students to appreciate the different variations of the Spanish language in Colombia as they learned different variations of English. Giving respect to and understanding variations of Colombian Spanish allowed Laura’s students to recognize that English is not the powerful utilitarian language it is made out to be, but just another language in which to communicate. Laura believes that her class has become a hub for social justice in the sense that the relation of power has been challenged, and students become active participants in the curriculum decision-making. Further, her students are not only empowered to use Spanish and other vernacular variations fearlessly in class, but are also engaged and motivated to learn about other cultures and languages while learning English.

The phenomenon mentioned above is best described by a concept that I have named trans[cultura]linguación, where there is a transaction between languages (and/or variations of the same language) while students learn about their own culture and about other cultures. For McLaren (2003), this central aspect of culture is a particular way in which a group lives and makes sense of its given circumstances and conditions of life, as expressed by their symbols and social practices, such as those found in music, dress, food, religion, dance, and education. Therefore, culture becomes as much an individual/ psychological construct as well as a social construct (Matsumoto & Juang, 2012), one which Laura and her students certainly use to create meaning in a Spanish/English learning environment.

To expand on this idea further, I borrow from translanguaging (García & Wei, 2014) and transculturización (Ortiz, 1983, p. 86), which describe how complex phenomena occur when multiple cultures trans-mutate in various directions within a specific context and among various individuals.4 With this in mind, I will define trans[cultura]linguación as the dynamic process in which the Spanish and English languages are juxtaposed with the merging and converging of cultures. Although this phenomenon may also occur in other contexts in which one or more languages (including Indigenous languages) are used to explain specific aspects about culture to make meaning in a specific learning task, in this article, I exemplify it by referring to the acknowledgment and learning of language variations and cultures from different regions of Colombia, and the learning of variations of the English language and its connected cultures within a pedagogical task.

Additionally, I can give another example that explains this phenomenon. When I was an ELE (Español como lengua extranjera / Spanish as a foreign language) teacher, I used to compare the different geo-cultural variations of English in the USA, in Canada, and the world, with the different variations of Spanish in Latin America. In this example, I used to compare vernacular English with Standard English, and then contrast it with vernacular variations of Spanish in various regions in Latin America. In other words, the concept of trans[cultura]linguación5 refers to two things: (a) the level of knowledge a person has of both variations of Spanish and English to make meaning and navigate their social lives, depending on the cultural location; and (b) the approach of teaching culture and linguistic variations of both English and Spanish based on different contexts, which requires the teacher to be knowledgeable of the two (or more) languages and two (or more) cultures. I acknowledge that teachers may not be knowledgeable about all the cultural and linguistic repertoires of the two cultures, however, trans[cultura]linguación refers mainly to how teachers and students engage the cultural knowledges they possess and the possibilities they have to learn more about other cultures and subcultures in a pedagogical task. In other words, how the class can be sparked into a curiosity that propels them to learn more about the local cultures of other students in the classroom, as well as other global cultures.

Unlike some EFL teachers who believe that students will best learn English by conducting class exclusively in English, Laura believes that she has challenged that notion by allowing her students to use their first language, Spanish. By adopting a trans[cultura]linguación approach, Laura has demonstrated that she could help to remove barriers to learning by creating an enabling, inclusive environment that validates first language identities and allows students to use Spanish to make meaning.

Finally, I posit that trans[cultura]linguación may become one more approach available to challenge static models of language teaching and learning, not only in multilingual locales of the Global North, such as New York, Toronto, London, and so on, but also in other locations of the Global South in Latin America, such as Bogota, Mexico City, and Buenos Aires. Students will not only learn the subject matter, but also learn more about their own culture and that of others from their own local country. They will thus be provided with opportunities to reflect on linguistic variations from different urban, rural, and regional locations.

A quote from García and Sylvan (2011) provides an apt conclusion to this section:

Teaching in today’s multilingual/multicultural classrooms should focus on communicating with all students and enabling them all to negotiate challenging academic content by building on their different language practices, rather than simply promoting the teaching of one or more standard languages. (p. 386)

To this end, I invite teachers and researchers to reflect on the different cultures and individuals interacting in the language classroom. As demonstrated in Laura’s classroom experience presented in this article, Colombian students from different departamentos (provinces/states), who speak different variations of Spanish, had the potential to learn about themselves and their own regional cultures while simultaneously learning English.

Final Reflection and Implications

In this contemporary globalized world, we are more connected than ever before, and languages and cultures no longer exist in hard-to-reach, isolated silos. Students pursue English language learning for economic and social mobility, and in the process are losing or beginning to devalue their own home languages; they are failing to recognize that bi/multilingual learning is a valuable asset (Cummins, 2001). For instance, research clearly shows that students with strong reading skills in their home language will also have strong reading skills in their second language (August & Shanahan, 2006; Riches & Genesee, 2006). Although, according to Laura, some English teachers still believe that Colombia has been portrayed as a monolingual/monocultural country, her pedagogical approach challenges this image. As de Mejía (2006) points out, Colombia has a rich diversity of cultures and languages, and this needs to be clearly acknowledged, recognized, and factored into English language teaching. Within this context, I contend that now is the time to value and embrace different variations of the Spanish language, as well as to value the country’s own Indigenous languages represented in many Colombian classrooms and schools.

Laura’s classroom experience may serve as an example to inspire other teachers to explore how pedagogical tasks can be used to make linguistic connections while also learning English. The fact that her students possess knowledge of Spanish variations from the different regions of Colombia helps to demonstrate that students are not monolingual in the strict sense of the word; as Piccardo (2013) said, “we are all plurilingual”, and thus attention must be paid to students’ linguistic and cultural repertoires, so as to ensure a more holistic education in English language teaching.

With this in mind, Cenoz (2013) focuses on three dimensions of holistic views on multilingualism: multilingual speakers, their entire linguistic repertoire, and their social context. Considering this, I think the teaching of language(s) in Colombia may be inspired by

a holistic approach [that] aims at integrating the curricula of the different languages to activate the resources of multilingual speakers. In this way, multilingual students could use their resources cross-linguistically and become more efficient language learners than when languages are taught separately. (Cenoz, 2013, p. 13)

What this means for bilingual (Spanish/English and other Indigenous languages) teachers is that they could develop activities in which different variations of Spanish expressions from various Colombian regions are integrated within English language learning tasks. Ultimately, a more holistic curriculum which allows flexibility and fluidity in language teaching and learning, one which fosters “flexible bilingual pedagogy” (Creese & Blackledge, 2010, 2011), can be developed. Based on the above, I propose three implications for a framework towards achieving a flexible and fluid holistic curriculum for English language teaching in Colombia and elsewhere: (a) equal education, (b) teacher education, and (c) language research.

Equal Education

In a country where in most elite schools, the curriculum is offered in English as the medium of instruction (de Mejía, 2011), translanguaging could potentially offer an instructional space for public school students to make meaning while discussing issues that are relevant to their communities. Thus, a curriculum that integrates plurilingual and translanguaging ideas has the potential to create equal opportunities for public school students to use their home language as a support and scaffolding for learning English in a less stressful manner. This suggests a paradigm shift in which the linguistic repertoires and language variations (in this case, of Spanish and English) and Indigenous languages are recognized, respected, and valued in the schools by keeping in mind what trans[cultura]linguación is. In this way, language education gains the power to dismantle monolithic narratives of the ideal English native speaker, and dispel the assumptions, beliefs, and practices that fuel the monolingual bias (Escobar-Fallas & Dillard-Paltrineri, 2015). Within such a framework, students would not worry about attaining higher levels of oral proficiency by trying to imitate the native English speaker but will rather learn English while affirming their own identities (Cummins, 1996) as Colombians, thus balancing the cultural and linguistic forces to make learning more equitable, especially for students in public and underfunded schools. Hurst and Mona (2017) have suggested that translanguaging pedagogies may best benefit students who are disempowered by English-only language ideologies. Furthermore, according to Laura, her class certainly became a hub to challenge such ideologies and it encouraged students to respond to issues of violence and aggression in the school in a context where Colombia is attempting to transition to being a more peaceful society.

Teacher Education Programs

Most teacher education programs in Colombia continue to advocate for communicative language teaching approaches that favour English-only policies, given that this is what is expected by government and institutional authorities. This negatively affects marginalized communities in the country (Usma, 2009a, 2009b; Usma, Ortiz, & Gutierrez, 2018). This points to a need for change in how teachers envision a classroom where more socially-just oriented pedagogies are more inclusive of cultural and linguistic practices (Sierra-Piedrahita, 2016). In-service and pre-service teachers in Colombian public schools need to gain a deeper knowledge of plurilingualism and translanguaging, what these concepts mean, and how they can contribute to the effective teaching of English. Both professional-development programs and bilingual-education programs will benefit from including theoretical, practical, and research courses on these topics, and language-education programs can integrate courses that teach the importance of students’ home languages and their linguistic variations, especially as students gain awareness of other cultures and languages.

It is important in today’s globalized world that as students are exposed to languages and cultures across the planet through the internet and social media, they acquire the relevant codes and skills. Accordingly, in order for teachers to not lag behind the rapidly evolving Zeitgeist, teacher-education programs need to equip students in their charge with the needed skills. Laura’s classroom practices may present a sound example as to how teachers can incorporate simple activities to activate students’ curiosity for learning about other cultures and languages, and as a means of fostering more sustaining pedagogies (Paris & Alim, 2017) that favour marginalized communities in Colombia. Laura’s classroom experience is a miniscule example of how teachers have already begun to push back at the established linguistic hierarchy from the bottom up, so that they can bring about meaningful pedagogical changes.

Language Research

Colombian researchers may find interesting connections in exploring the relationship between Spanish and learning EFL and the role Colombian Indigenous languages can play in the learning of other languages (English included). Although there is emerging research in Colombia investigating current teaching practices, and further social research among undergraduate students and in-service teachers (see Escobar, 2013), more attention can be paid to the system of semilleros de investigación (research incubators), very popular among teaching education programs across Colombia. These research groups at undergraduate and graduate levels can potentially use the resources they already have to advance research on plurilingualism, translanguaging, and their relationship with Colombian cultures (ethnic cultures, subcultures, urban cultures, etc.). Additionally, now that Colombia is in a post-peace accord era, this presents an opportune time for teachers and researchers to potentially explore the connections between social justice and peace education in EFL. These themes are no strangers to the goals of plurilingualism, which are “to perceive the language teacher (who teaches the mother tongue, the language of the school or foreign languages) as an individual who has social responsibilities, including responsibilities towards oneself as a plurilingual and intercultural speaker, and towards others” (Bernaus & European Centre for Modern Languages, 2007, p. 16). For Oliveira and Ançã (2009), the realization of these goals calls for training language teachers and teacher researchers who can help their students to become more aware of the context in which their communication and learning experiences take place, and to become agents who represent an evolving plurilingual competence. To this end, research methods such as collaborative action research (CAR) and youth participatory action research (YPAR) have the potential to engage both teachers and students in (re)discovering languages and cultures, and the role these play in the current sociopolitical environment in Colombia.

Ultimately, there is an urgent need to see students’ cultural and linguistic diversity not as impediments to learning languages, but as cultural-capital resources that they bring from home to school. Once this is clearly understood, the intellectual capital of our societies will grow dramatically (Cummins, 2001), fostering a new generation of students who can become agents of social change. I concur with Alexander and Busch (2007), who agree that

the maintenance and promotion of multilingualism is essential in the modern world because of its implications for diversity, development, democracy, didactics and (human) dignity [and] depriving a person of the free and spontaneous use of his or her mother tongue constitutes a violation of a fundamental human right. (p. 15)

Throughout this article, I have suggested that plurilingualism and translanguaging are key concepts for the teaching and learning of EFL in Colombia (and, for that matter, in any number of other countries). I have also argued for change from a monolithic framework of learning language(s) to a more dynamic and fluid one that uses trans[cultura]linguación as a point of departure for a paradigm shift in language pedagogy. This, I strongly believe, will ensure equitable pathways for all students, regardless of socioeconomic and class status, or their geopolitical location, to successfully learn and value their own languages as they learn English, and to do so while addressing issues that are relevant to their communities. So, when a student, like one in Laura’s English class, asks: “Teacher, ¿puedo hablar en español?” The answer is a convincing “¡Sí! Yes, of course!”