Introduction

Research in the area of assessment of oral performance is abundant in English as a second/foreign language (ESL/EFL) literature but, if we focus more attentively on the assessment of pronunciation, the scope immediately diminishes, which is an indicator that the interest in this field is not highly regarded when compared to that in some other skills. Furthermore, considerations on the differences between the way in which native English speakers (hereinafter NES) and non-native English speakers (hereinafter NNES) assess pronunciation are practically inexistent in the literature. This does not mean that there is an absence of research concerning this divide between NES and NNES teachers; it only means that these works usually have a different scope. For instance, Martínez Agudo (2017) has explored the relevance and significance of both types of ESL/EFL teachers and their roles as facilitators of learning. On the other hand, Isaacs and Trofimovich (2017) have begun to shed new light on the challenges that both NES and NNES teachers face when assessing ESL/EFL pronunciation, yet in their work there is no explicit comparison between the way in which NES and NNES teachers evaluate pronunciation. Davies (2017) refers to the concept of the native speaker stating that it is a contentious one. He focuses on the attacks they usually experience, most of them related to political rather than linguistic considerations. In relation to this, it is important to clarify that the present study does not intend to criticize the role of NES (or NNES) teachers whatsoever. The view of the native speaker, in this study, is merely defined by the factors described in the methodology, such as having been born in an English-speaking country.

NNES teachers perceive that NES tend to be, sometimes, more indulgent when assessing not only pronunciation, but also oral performance as a whole. Of course, this premise does not constitute evidence of any kind, but the sole idea that NES may indeed assess students’ performances in a more lenient fashion when compared to NNES cannot be taken lightly as it would have important implications in the activity. First, and as obvious as it may sound, students do not feel comfortable with low marks, and many of them will surely avoid the stress caused by these low marks whenever possible. For instance, if a phonetics course in a given English teacher training program is offered in two separate sections, one taught by an NES teacher and the other by an NNES teacher, the differences in marks regarding oral production-which is usually the most important part of the course-may potentially lead to comparisons and conflicts among students. Such comparisons might even, in turn, have repercussions among teachers and authorities of the program or department and even with the institution. Without stating any judgment on the value of grades in education, the fact that they are an element that requires and receives attention in current educational systems must be acknowledged. Having a good or bad mark can make a difference, since there is a reason many universities in the world require students, for instance, to score highly in their secondary education accomplishments to be accepted in their programs. Additionally, marks are also important to obtain grants and subsidies for academic purposes. Therefore, the differences found between the two groups of teachers would be relevant, especially considering that the presence of NES teachers in the so-called expanding circle (Kachru, 1985) is not likely to change in the foreseeable future.

The present study is guided by the following research questions:

Are there differences in the ratings NES and NNES teachers assign students when evaluating their pronunciation?

In case these differences are present, are they significant in the context of higher education?

Are there any differences in the ways in which NNES and NES teachers approach the evaluation task?

In the first part of the article, a framework of relevant literature is provided followed by the methodology, including all the procedures to carry out the research. Then, the results and discussion are presented together. Finally, the conclusions and the most relevant findings, interpretations, and implications in the field of ESL/EFL are offered.

Theoretical Framework

Pronunciation in EFL and ESL contexts

Speaking skills have always been important in the teaching and learning of English as a foreign or second language, but those with several years of experience in the field know that the aspect of pronunciation has usually been neglected. In a recent study, Edo Marzá (2014) discovered that, in most Spanish-speaking countries, there is an evident tendency to overlook the teaching of pronunciation in EFL settings, and that the focus of instruction lies mostly on grammar, reading, and writing skills. Additionally, Gilbert (2010) has estimated that pronunciation continues to be overlooked in the ESL and EFL contexts. On top of all this, not all teachers seem to be receiving proper training in pronunciation. Actually, Breitkreutz, Derwing, and Rossiter (2001) conducted research in Canada, and concluded that most instructors receive little to no training in the specific area of pronunciation. Despite the lack of research in Chile, our reality does not seem to differ from the above situation, since training programs do not commonly include independent modules-core or elective-aimed at reinforcing this area in learners, relying only on the teacher’s sensitivity to deal with particular problems in the classroom. This limitation may present further risks because, even though most English teacher-training programs include two semesters of English phonetics as a minimum, these courses do not usually prepare students on how to teach pronunciation.

Until not so long ago, research in the field seemed to mirror the problem related to the professional activity mentioned above. Asher and Garcia (1969) argued that pronunciation in second language acquisition (SLA) was less studied than other components due to the different variables that are involved in the process-gender and motivation, among others. Four decades later, Derwing and Munro (2005) stated that published research on the teaching of pronunciation is significantly smaller when compared to areas such as grammar and vocabulary, and teachers often end up relying on their own intuition rather than on empirical evidence to assess their students’ oral output. Besides, Kang (2010) has similarly noticed that there has been little research on the teaching of pronunciation in L2 contexts. Recently, though, there have been noteworthy works on the matter. Isaacs and Trofimovich (2017), despite the absence of a comparison between NES and NNES teachers, refer to several aspects relevant to this study, such as the fact that some teachers only focus on comprehensibility when evaluating oral production, whereas others consider near-native or free-accent pronunciation as an important factor. They also refer to the debate on what the appropriate standard should be, as well as the pronunciation features that should be prioritized.

Concerning the latter point, neither NES nor NNES teachers receive any specific training in the teaching of pronunciation. Since NNES teachers need to experience acquisition formally, they may naturally develop a degree of awareness concerning the aspects of pronunciation that are more challenging. On the other hand, NES teachers can only rely on their own perceptions.

The Relevance of Interlinguistic Comparison

Robert Lado (1957) introduced the notion of contrastive linguistics. According to him, in order to solve the problem of what to teach, we need to carry out an interlinguistic comparison between the mother tongue and the target language as the former may facilitate the learning of certain elements, and it may also affect the learning process negatively. In light of this, Corder (1967) presents the concept of error analysis as a descriptive and comparative technique useful to the process of language teaching and learning. He points out that this technique serves to help teachers provide concrete solutions to problems in the classroom. One of the main problems regarding the role of contrastive analysis is that it assumes that all errors derive from interference with the learners’ mother tongue. Nonetheless, by means of the aforementioned error analysis studies, it has been revealed that certain errors, made by various foreign language speakers with different L1 backgrounds, are recurrent among them and seem to be more related to the intrinsic difficulty of the subsystem involved and not necessarily to cross-lingual influence. For instance, concerning the use of prepositions in English, it would be nearly impossible for a non-native speaker of English not to make mistakes regardless of whether or not their own mother tongue has prepositions (Lennon, 2008). Widdowson (2003) also points out that knowing the learners’ L1 is not the only helpful source of information, but that being aware of the “bilingualisation” process is just as meaningful. Despite the fact that there are various considerations that need to be taken into account in the area of pronunciation of a foreign/second language, the role of the mother tongue is important as a predictor of a series of potential errors students may present. For instance, the vowel system of English is a problem for speakers of most languages in the world as they have a relatively small inventory of vowels (five being the average), but Germanic languages have a larger number of vowels, so learning how to produce English vowels is far more accessible than for a Greek, Japanese, or Spanish speaker.

The students’ mother tongue appears to be a relevant item to most authors in the field. For example, Odlin (1989) believes that native language phonetics and phonology significantly influence second language pronunciation. Similarly, Akram and Qureshi (2012) refer to the positive or negative influence of the native language since learners tend to replicate their L1 speech habits in their target language. In fact, the relevance of the mother tongue is what makes it hard for teachers and researchers to map out a common ground for the specific hardships in second language learning, thus standardizing the practice. Some linguistic areas that may be affected by mother tongue interference in foreign language output are specific phonemic contrasts (Brown, 1988), segmental vs. prosodic errors (Anderson-Hsieh, Johnson, & Koehler, 1992; Johansson, 1978; Palmer, 1976) and the negative impact on overall comprehension (Fayer & Krasinski, 1987; Koster & Koet, 1993). In this study, our concern is not the degree to which Spanish L1 interference plays a role in the students’ pronunciation but to identify how the awareness of these areas of interference affects the judgements of NNES teachers.

As a whole, Spanish is a language that often poses difficulties for EFL/ESL students. Edo Marzá (2014) focuses on the many differences between Spanish and English in terms of phoneme production, linking phenomena, intonation and stress, and goes on to explain that all these traits may negatively affect Spanish speakers upon the production of oral speech. In the same vein, Florez (1998) argues that errors in aspiration, intonation, and rhythm in English are likely to be caused by Spanish interference. Shoebottom (2011) also highlights the consistency of Spanish spelling and pronunciation versus the corresponding inconsistency in English, which results in orthographic-like utterances. Coe (2001) has provided an outline of the most common areas of interferences or potential difficulties for Spanish speakers when attempting to produce English. Among such hitches are found “difficulty in recognizing and using English vowels, strong devoicing of final voiced consonants, and even sentence rhythm, without the typical prominences of English” (Coe, 2001, p. 91). All these hardships not only affect the learning process of students, but they may also have an effect on the perceptions of evaluators, particularly NNES teachers, who tend to be mostly aware of the influence of their mother tongue in the acquisition of a foreign language. In other words, the fact that they have achieved a relative success themselves in the target language may predispose them to be more demanding with their own students, as opposed to native speakers of English who never experienced language interference and, therefore, are unaware of the importance of L1. Put simply, even if NES teachers were trained on Spanish interference, the role of said interference would never be as significant as for NNES teachers due to their own experiences in learning the language.

NES and NNES Teachers and Evaluation

Literature on the differences between the ways in which NES and NNES teachers approach evaluation of oral performance is not abundant and, in the Chilean context, the material is even more restricted. One significant contribution regarding the teachers’ own perceptions in relation to assessment has been provided by Barrios (2002) who, in her research, albeit limited only to Spain’s reality, discovered that non-native English speakers saw themselves as more capable of evaluating students’ potential and of anticipating what their eventual areas of difficulty might be. It follows, then, that NNES teachers view the first language as an asset that NES teachers with no second or third language do not have. This idea, besides being supported by several authors and theories-e.g., Corder (1967)-is mainly predicated on their personal experiences learning English as a foreign language and is rooted in the fact that they literally have the know-how after having acquired English successfully in spite of the difficulties that it presented. On the other hand, NES teachers are usually seen by most people as the most reliable English language source. In fact, it is well known that many language institutions advertise their courses with the hook of native instructors. In spite of this enlightening finding, there are not many studies that have attempted to examine the manners in which NNES and NES teachers evaluate their students’ oral output.

Although the study carried out in Chile by Baitman and Véliz (2013) considered oral performance as a whole rather than pronunciation only, some of the conclusions appear relevant to the present study. The first and most important finding is that NES teachers, overall, tend to assess their students’ performances with higher grades on the speaking rubric than NNES teachers do. Although we cannot refer to conversations among NNES teachers as proper evidence, the findings of Baitman and Véliz mirror the general impression that many Chilean teachers have on this issue. Another observation made by Baitman and Véliz is that NES teachers often give more relevance to items such as fluency and pronunciation when assessing their students’ oral performance, while NNES teachers tend to focus more on grammatical accuracy and vocabulary instead. In a similar study carried out in China, Zhang and Elder (2011) found that, although there were no differences in rating between NES and NNES teachers, NNES raters appeared to be more form focused and less communication focused than NES. Their study also showed NES teachers were more likely to pay attention to features of interaction, while NNES focused more on linguistic resources such as accuracy. It follows, then, that the difference will be less significant in the present study, since it only focuses on pronunciation. On the other hand, the variables considered in the present study may not be comparable to any previous research.

Method

The purpose of this research was to determine qualitatively whether there were differences between the judgements of NES and NNES teachers when evaluating pronunciation and, in the event that there were such differences, to identify them. Through comments made by the teachers, the study also attempted to identify differences in the procedures that the two groups of teachers carried out, including the particular subfields of pronunciation present in the evaluation sheet: production of vowels, consonants, stress and intonation.

Sampling Design

Six NES and six NNES teachers were selected according to the criteria that follow. First, they were required to have a degree in the area of concern, either an English pedagogy and/or an ESL/EFL certification. Alternatively, they could also hold a degree in the area of applied linguistics. Regardless of their degrees, in Chile people who currently serve as teachers of English as a foreign/second language possess different academic backgrounds-some of them do not even have a degree. The participating teachers were also expected to have a minimum of five years of experience in the area of English language training due to the undeniable fact that teaching and assessing are, to a certain extent, processes of trial and error. Therefore, teachers who have accumulated a few years of experience tend to be less hesitant and pass judgments more definitively when evaluating language performance. Regarding the distinct requirements for NES and NNES teachers, the former were selected only if they had been born in any of the countries in which English is spoken as a first language, and had actively participated in those communities until adolescence. The latter, in contrast, were born in countries in which English is considered a foreign language and showed no command of fluent spoken English before adolescence. Authors such as Leung, Harris, and Rampton (1997) and Davies (2017) have claimed that variables such as nationality or ethnicity may be misleading to identify accurately native from non-native; hence, those variables were not considered in this study. The data were obtained from the evaluation of the 12 teachers who assessed four tasks produced by a first-year student and a second-year student participating in the teacher-training program at a major private university in Santiago, Chile. Each student recorded two files-an interview and a reading passage-and the differences in each student’s level of English was a conscientious decision in order to explore another possible variable that may potentially interact with the perceptions from each evaluator. Out of 12 samples obtained from six first-year students and six second-year students who recorded their tasks, only two were selected. The selection criteria included extra linguistic variables, such as voice volume, sound quality of the recording, and even discourse coherence in order to avoid any interference with the focus of the evaluation, which was pronunciation.

Materials

The materials developed for this project included the following components:

Audio files. Four audio files produced by the speech of two students were sent to each participant. Two of the files consisted of spontaneous speech, each one lasting three minutes approximately. Both recordings were obtained by means of an oral interview including various questions mainly about the personal background of the two students. Additionally, students recorded two more audio files of approximately 40 seconds, each containing a written text read aloud by the two students. The text used was developed considering some of the areas of interference between English and Spanish with the purpose of eliciting specific deviant forms.

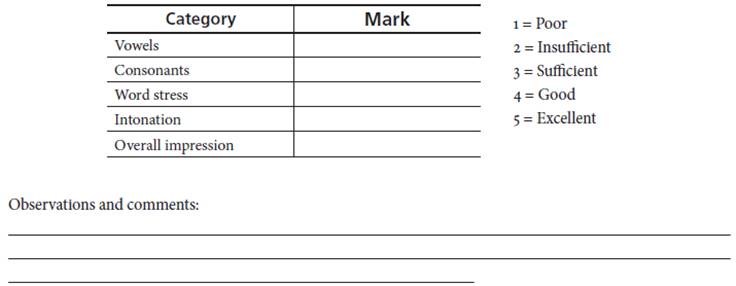

Evaluation sheet. An evaluation sheet (Appendix A) was included to collect the data from each teacher. This sheet did not include descriptors so that the teachers could freely jot down their own perceptions rather than refer to pre-defined specific ratings. However, specific categories in the area of pronunciation were included. Segmental features, which involve sounds-namely vowels and consonants-and suprasegmental features-which are present across and beyond segments-including word stress and intonation. Extra variables, such as rhythm or sentence stress, were not included because they require the expertise of highly specialized teachers with an ample knowledge of phonetics, which was not a requirement for the participants in this study.

Directions for evaluation. Finally, specific instructions (Appendix B) were provided to each teacher to avoid any significant differences in the assessment procedure.

Procedure

Recordings, scale of evaluation, and procedural instructions were sent to the participants involved in the research (teachers), and they were required to assess each recording including comments and observations on each category. They were required to send back their results within a period of two weeks. After data collection, the scores provided by NES were compared with those provided by NNES, and the same procedure was carried out. On this second occasion, the differences between the two students were evaluated. Additionally, comments made by the subjects were analyzed in order to identify evaluation patterns in NES and NNES.

Results and Discussion

Table 1 presents the ratings provided by both groups of teachers, NES and NNES. The Chilean marking system sets 60% as the minimum level of achievement for a passing grade. Both groups of teachers were asked to assess the students’ performances with marks ranging from 1 to 5, with 3 being the minimum passing mark.

Table 1 Evaluation Ratings by NES and NNES Teachers for Each Student and Task

| Student A 58. | Student B 60. | |||||

| Reading Task | Speaking Task | Reading Task | Speaking Task | Mean Score | Standard Deviation | |

| NES teachers | 3.7 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 0.65 |

| NNES teachers | 3.2 | 3.9 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.7 | .0.99 |

The assumption that NES teachers are not as demanding as their NNES counterparts to evaluate students’ pronunciation is confirmed by the results in Table 1. Both NES and NNES teachers rated Student A higher than Student B-which is consistent with the level of the students. In fact, considering a 60% scale of achievement, both NES and NNES teachers passed Student A and failed Student B. However, if we look at the mean score from each group, we find that NES teachers rated 3.3 (SD = 0.65) after all four tasks, which correspond to 66% of achievement, while NNES teachers rated 2.7 (SD = 0.99), which corresponds to 54%, thus showing that the ratings actually become more significant when combining the results of both students. As for the reasons why NES teachers rate students higher, their comments on the evaluation suggest that NES teachers focus on comprehensibility-or focus on meaning, which is directly related to understanding oral output at a macrostructural and cultural level (Jung, 2010)-while NNES teachers concentrate on form. Notes on the assessment sheets of the type “I had no problem to understand the speaker” are numerous in the NES group, which would suggest that they concentrate on comprehensibility rather than form. The above comments are actually rare in the assessment sheets of their NNES counterparts as most of them focused on deviant forms present in the students’ oral production, which is consistent with the findings of Fayer and Krasinski’s study (1987). Additionally, their ratings may largely be based on their lack of proper training on English phonetics as argued by Gilbert (2010) and Breitkreutz, Derwing, and Rossiter (2001), among others. Furthermore, the NES teachers’ evaluation of both the speaking and the reading tasks by both students was higher than that of NNES teachers. An additional reason for the aforementioned differences may be presented now from the perspective of the NNES teachers. As mentioned above, NES teachers do not take courses of pronunciation, but NNES teachers do. Traditional universities in Chile include a minimum of four semesters of English phonetics on average. Despite the fact that students are not actually trained to “teach” pronunciation, the training they receive is, overall, rigorous. It includes a detailed theoretical description of the English phonological system (both at the segmental and the suprasegmental levels), as well as practical activities, like sound-discrimination, drillings, phonetic transcription, among others. After this training, students are not only prepared to comprehend English but also to discriminate output that does not resemble any of the traditional models (British or American standard accents), which are still used in universities in Chile. The fact that all the NNES teachers in the present study have been exposed to that type of learning experience may make them predisposed-consciously or unconsciously-to setting higher expectations on the performances of the students. Another important indicator of the differences in training between the two teacher groups concerns the type of language used in the comments. The amount of technical terms belonging to the field of phonetics and phonology was overwhelmingly greater in the comments made by the NNES group. Words such as “schwa,” “bilabial,” “fricative,” “acoustic,” “neutralization,” “elision,” “clusters,” “canonical,” and others were used by NNES teachers. On the other hand, NES teachers used none of these terms with the exception of certain labels that are found in everyday English, such as “foreign accent” and “good ear.” For NES teachers, there seems to be a paradox in the use of the term “foreign accent” when talking about comprehension since, as stated by Munro and Derwing (1995), these are non-related concepts. Actually, they have demonstrated that heavily accented speech may also be completely comprehensible. This pervasive notion is still a common misunderstanding as demonstrated by the same study.

In Table 2, we can see the same tendency presented in Table 1, since NES teachers rated each one of the criteria higher (SD = 0.59) when compared to their NNES counterparts (SD = 0.85). The only exception was the category of word stress in Student A, which was rated exactly the same. This may be explained by the actual number of mistakes-no more than two-which was simply not enough to produce a difference in perception between the NES and NNES teachers. This idea is further supported by the fact that the mark is relatively high (3.9 out of a maximum of 5).

Table 2 Evaluation Ratings by NES and NNES Teachers for Each Criterion

| Criteria Evaluated | ||||||||||

| Vowels | Consonants | Word Stress | Intonation | Overall Impression | ||||||

| St. A | St. B | St. A | St. B | St. A | St. B | St. A | St. B | St. A | St. B | |

| NES teachers | 4.1 | 2.9 | 4 | 2.6 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 2.8 |

| NNES teachers | 3.5 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 2.5 | 3.9 | 2.5 | 3 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 2 |

Another factor that reflected the more holistic appreciation of the performance by NES teachers as opposed to the narrower, more form-based evaluation made by NNES teachers is also present in the comments. NES participants wrote notes such as “It seems she didn’t understand what she was reading” and “I noted that the speaker lacked confidence.” These comments were based on more pragmatic elements that are not traditionally considered when the assessment focuses on pronunciation regardless of other extra linguistic elements that are also part of communicative acts. In contrast, NNES teachers showed no concern for such elements and seemed to have concentrated only on linguistic features, which was illustrated by comments like “vowels interfered by Chilean Spanish,” “lack discrimination between alveolar, plosives and dental, fricatives”, “no overt differentiation of vowels 1-2 and 4-5”, “production is orthographically based”, among others. These findings are highly consistent with the one found by Zhang and Elder (2011).

The distinction between what is correct or incorrect is naturally more rooted in NNES teachers. Another point that illustrates this distinction concerns intonation and the comments made by the two groups. One of the students in the speaking task consistently produced a rising intonation at the end of every utterance regardless of whether it was a statement or a question. NNES teachers described this pattern as being “incorrect,” “wrong,” or simply “not suitable,” while NES teachers (three of them, to be precise) associated the feature with “California Valley intonation”, which, although it is stigmatized as a trait of ditzy or intellectually superficial speech, is not incorrect as, for them, it is an obvious possible form in which people speak English. Without making any technical judgments regarding the way in which both groups faced the process of assessing pronunciation, it is noticeable that there are differences in the way in which both groups viewed the task. In fact, considering the language employed in the comments, it is surprising not to find a bigger gap in the ratings. The differences in their assessments and the comments provided by both groups of teachers suggest an overall differentiation in their roles in the assessment and what the assessment task entails. In other words, their own performances exhibit differences that are largely based on and imbued by their own backgrounds and professional training, which they extrapolate to their teaching practices. Consequently, their professional performances differ in both intent and form.

Conclusion

The objective of the present research was to determine whether there were any differences between the way NES and NNES teachers evaluate pronunciation of students, and to explore the aspect in which the procedures they carry out differ. NES teachers of English seem to rate performances higher than their NNES colleagues. Even though the differences may not appear statistically significant in number, NES teachers constantly rated higher not only the overall performance of each student, but also the students’ performances for each criterion. However, both groups of teachers can similarly identify a weak from a strong performance between the tasks and students evaluated.

Taking into account the comments made by each group, one can see it follows that NES teachers have a more holistic approach towards the assessment of pronunciation as they appear to consider elements that are not necessarily within the purely linguistic categories, but which can rather be more closely associated with the area of pragmatics and communication as a whole. On the other hand, NNES teachers are far more structured in the way they assess precisely because the training they had as students was geared toward being structured, error-oriented and, in the end, much more punitive.

It seems logical that one possible solution to minimize the effects of differentiated assessment by NES and NNES teachers is to hire teachers with very similar backgrounds, training, and qualifications; however, this procedure is not only hard to achieve-since teachers in reality come from different backgrounds-but it is also discriminatory as not all applicants would be given the same or similar opportunities. A far more sensible solution would be for institutions to organize workshops in which all teachers share and discuss the criteria they take into account for the assessment of their students’ oral production. By so doing, they would be able to outline and consolidate policies (Jenkins, 1998) with the purpose of reducing the differences above, thus standardizing criteria to assess students as fairly and objectively as possible. This issue should be seriously undertaken by institutions, especially if English is being taught for professional purposes as there may be cases in which injustices could be made. Such amendment is especially significant if we consider that in many institutions both NES and NNES teachers cohabit and assess students’ performances on a daily basis, thus making room for the aforementioned discrepancies.

Besides having a bigger sample, future research in this area could incorporate a follow-up study for teachers to provide relevant reflections about their assessment practices and, in doing so, obtain insights on how to improve the assessment procedures in the area of pronunciation not only restricted to the context of teacher-training education.