Introduction

English as a global language has spread all over the world not only in second language settings, but also in foreign language contexts. According to Matear (2008) “the number of people learning English as a foreign language is growing across [Latin America]” (p. 131); this is because this language has the status of the Lingua Franca (Gómez Burgos & Pérez Pérez, 2015; Harmer, 2003); the international language (Pennycook, 1994); and the language of business, science, and technology worldwide. The status of English promotes people’s wishes and needs for learning that language and, at the same time, gives people more opportunities to become more competent in the world of work. Similarly, it is widely recognized that being competent in English opens doors to access a number of opportunities in different areas such as cultural exchange, knowledge, business, and education.

In Latin American countries for many decades, knowing English was mainly a hallmark of the economic and political power of the upper echelons of society (Matear, 2008) because wealthy people had easier access to learn this language; then, they were better prepared to face this new requirement of the globalized world. Recently, however, governments in Latin America have proposed new educational policies which promote the insertion of English in the curricula of their countries in publicly funded schools during the last years (Lindahl & Sayer, 2018); these new proposals are intended to democratize the teaching of the language, and people from lower and middle classes may see this initiative as an opportunity for them to be better prepared and to obtain better jobs in the near future.

In the case of Chile, teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) has gained importance during the last decades. As a consequence, English was included as the compulsory foreign language in the Chilean curriculum during the 1990s, starting in year 5 in elementary education until year 12 in secondary education. With the new educational reform in 1998, English was presented as a primordial skill in the new curriculum in order for it to develop competencies in students to obtain access to information and facilitate international communication and business (McKay, 2003). From this period onwards, EFL has been taught in the Chilean classrooms and its coverage broadened via its insertion from first cycle in primary levels in the last ten years. However, results of the last national examination applied to measure 11th graders’ English level showed that fewer than 20% of them obtained an A2 certificate of proficiency (Gómez Burgos, 2017).

A similar situation has occurred in Chilean tertiary education. Nowadays, English is part of many study plans (Matear, 2008) of diverse programs in the areas of science, engineering, health, arts, and humanities. This insertion has been done by including English courses in the curriculum of undergraduate programs to give the students access to scientific information written in English and develop professional language skills in the target language. But, in spite of having more English courses at university level, results from international tests revealed the very basic knowledge of English students hold. For example, a study conducted by Education First (2017) placed Chile in number 45 of 80 participating countries and in the category called “low proficiency” of language use; this aspect reflects that a considerable number of Chileans have a very limited management of the foreign language.

Bearing in mind the previous information concerning the inclusion of EFL in Latin America, but mainly in Chile, we can see that many factors might influence the students’ low proficiency in English, especially affective variables such as motivation and attitude. Hashwani (2008) informed that positive attitudes towards a language are a fundamental factor in the process of learning a foreign language. Nonetheless, studies in this field have not been reported in Chile in tertiary levels during the last decade even when attitudes towards a language have been reported as crucial factors in language learning (Fakeye, 2010) in different levels of education. In this regard, Gómez Burgos and Pérez Pérez (2015) and Kormos and Kiddle (2013) suggested that there is limited research conducted in the field of affective factors in EFL in Chile, which leads us to believe the present study contributes to expanding the existing literature in the area.

Considering the above-mentioned factors, we see this research reports on the attitudes of a group of 131 university students towards EFL in Chile. Simultaneously, this report intends to characterize the way undergraduate students perceive EFL, especially in the south of the country, by analyzing their responses given to the 78 statements of the questionnaire applied in the three different dimensions of attitudes, namely: behavioral, cognitive, and emotional.

Affective Factors in EFL Learning

In light of the new tendency that shows the increment of EFL learners in the region, but the low results of people’s language proficiency, an interesting topic in this area has to do with affective factors that interfere positively or negatively in the process of language learning (Ahmed, Aftab, & Yaqoob, 2015; Hashwani, 2008). Studies in the area have reported the relevance of these variables when learners face the complex process of second language acquisition, and even more complex, foreign language learning, not only because it is time demanding, but also because it is a difficult process when negative variables intervene.

Studies about affective factors affecting EFL learning are limited in South America. Puerto Zabala and Reyes Vargas (2014) reported on a group of Colombian students’ perception of EFL towards English for specific purposes; results evidenced that students are conscious of the importance of English in the globalized world. Similarly, Peña Dix (2013) completed a study in Colombia and concluded that EFL learning and teaching are complex processes where motivation plays a foremost role. In the same way, Chilean students, their parents and 2017eachers are reported to hold favorable perceptions towards the management of the English language since its use improves future job and study opportunities (CIDE, 2004). A similar study carried out by Gómez Burgos and Pérez Pérez (2015) concluded that 12th graders held a favorable perception towards EFL because they consider the target language essential for their future; however, they do not want to devote time to it. All in all, the conclusions of the reduced studies in the field agree on the importance of affective variables in the process of learning EFL.

Kormos, Kiddle, and Csizér (2011) established in their study that the most significant learning outcome of the students had to do with “the status of English as a lingua franca, and the wish to use English as a means of international communication” (p. 513); and acknowledging that an “ESL/EFL learner’s motivation is affected by learner’s attitude towards learning language” (Noreen, Ahmed, & Esmail, 2015, p. 96). We expect Chilean undergraduate students hold favorable attitudes towards EFL. It is clear that favorable attitudes towards a language positively predispose learners to its learning process; therefore, attitude is an essential variable to consider when teaching and learning EFL.

Attitude in EFL Learning

Attitude has been regarded as a key factor in learning a foreign language. According to Zainol, Pour-Mohammadi, and Alzwari (2012), attitude is one of the key affective issues for success in learning a foreign language; it plays a crucial role in the learning process since it is a predisposition towards an object which can be either positive or negative. In the case of foreign language learning “positive language attitudes let learner [sic] have positive [sic] orientation towards learning English” (Karahan, 2007, p. 84); consequently, when facing a teaching-learning process like learning a language, the learner’s mood with a favorable foundation is more suitable than a learner with an unfavorable basis. Positive inclination towards the language has an effect on the process of learning the language.

Additionally, Wenden (1991) proposed a definition of attitudes that covers three dimensions, namely, cognitive, affective, and behavioral. First, the cognitive dimension has to do with the individual’s beliefs or opinions about the object; second, the affective component alludes to the individual’s feeling and emotions towards the object; and third, the behavioral constituent refers to the individual’s behavior or actions towards the object. Therefore, attitudes are made up of all three components and, in the case of foreign language learning, they suggest “linguistic behaviour in particular” (Al-Mamun, Rahman, Rahman, & Hossain, 2012, p. 200) because they have a clear influence over our behavior resulting from the social activities performed by using the target language (Gómez Burgos & Pérez Pérez, 2015).

In the last decade, many studies have revolved around the issue of attitudes learners at different levels have towards EFL. Concerning university students’ attitudes towards EFL, Soleimani and Hanafi (2013) recently conducted a survey of 40 Iranian medical students; their findings indicated that the participants held highly favorable attitudes towards the language. In the same year, Tahaineh and Daana (2013) informed of 184 Jordanian undergraduates’ motivations and attitudes towards learning EFL; their findings showed the positive support English enjoys for participants’ instrumental use. Likewise, Al-Tamimi and Shuib (2009) described a research study about petroleum engineering students’ motivation and attitudes towards learning English; their findings revealed that learners held positive attitudes towards the use of English in social and educational contexts. All the studies informed above reported on favorable attitudes towards English as a universal language and highlighted the importance of English in the globalized world.

In regard to Chile, McBride (2009) investigated the students’ perceptions about the techniques used when teaching EFL in Chile. Results showed that students had positive perceptions towards English, especially concerning its use in order to facilitate communication with other language speakers. In this line, it seems the evidence shows that Chilean learners hold positive attitudes towards the target language; however, the inexistence of studies reported in tertiary education in this area makes it difficult to definitely conclude in this regard. As stated previously, this study aims to investigate and report on a group of 131 university students’ attitudes towards EFL in Chile in order to characterize their attitudes towards the target language at university level.

Method

This research project is a descriptive survey study that uses quantitative methodology. It aims to characterize a group of university students’ attitudes towards EFL by means of their responses given to the statements on a questionnaire.

Participants

The participants were 131 students from four different universities in the south of Chile who answered an online questionnaire; 68 respondents were women (52%) and 63 respondents were men (48%). Their ages were varied: 49 respondents ranged in age from 17 to 20 (37%), 75 respondents ranged from 21 to 25 (57%), 6 respondents ranged from 26 to 30 (5%), and 1 respondent was more than 30 years old (1%). The participants’ fields of study were varied as well; 8 respondents were from arts and architecture (6%), 1 participant from education (1%), 67 participants from health (51%), 32 respondents from engineering (24%), 22 participants from social sciences (17%), and 1 respondent from another field (1%). In regard to the respondents’ year of study in their programs, 4 participants were in their first year (3%), 55 students were in their second year (42%), 26 respondents were in third year (20%), 13 students were in fourth year (10%), and 33 students were in fifth or senior years (25%).

Data Collection Instruments

A questionnaire was designed to gauge or probe a group of university students’ attitudes towards EFL in the south of Chile. It was developed based on the analysis of previous related instruments (see Gómez Burgos & Pérez Pérez, 2015; Soleimani & Hanafi, 2013; Tahaineh & Daana, 2013). The instrument was also previously piloted and refined in order to measure the reliability level of the different items; similarly, it was proofread by three professors to corroborate the validity of the items of the questionnaire. All comments received were considered at the moment of modifying the instrument before applying it.

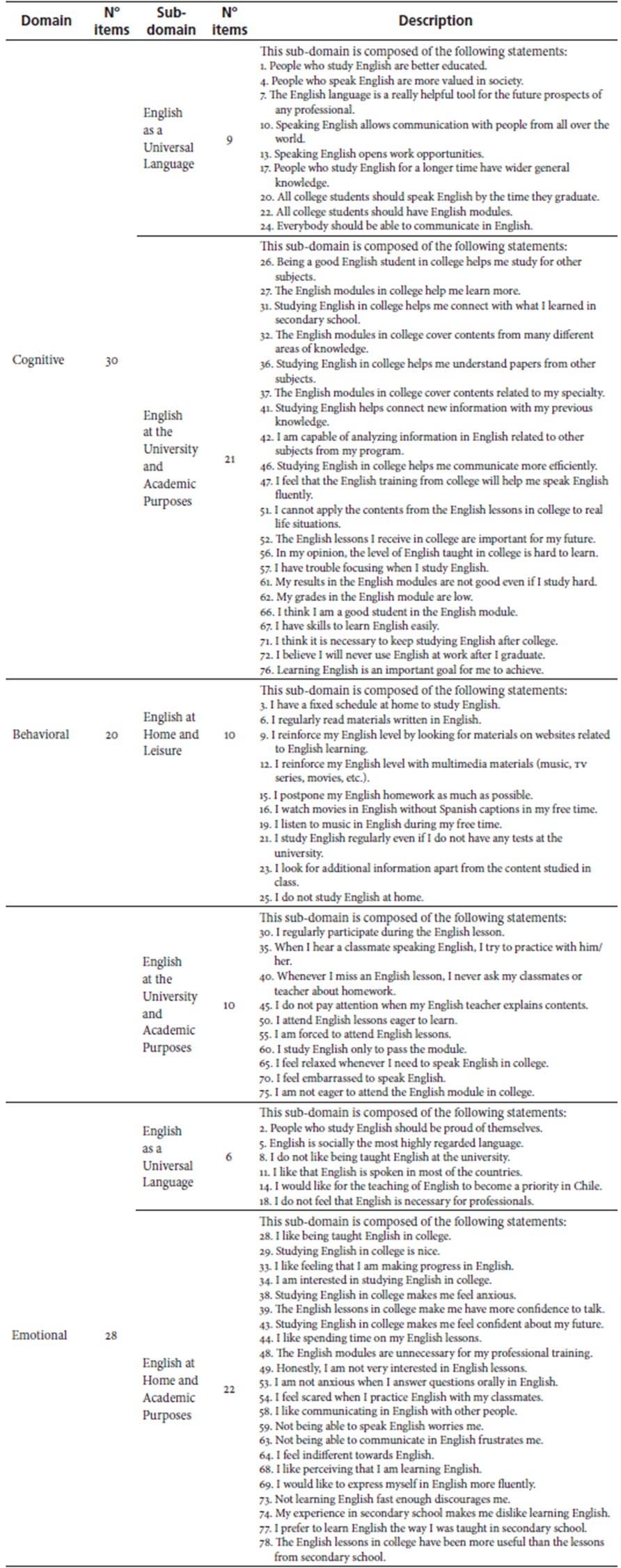

The questionnaire has two main parts: the demographic information and the statements related to the three domains of the instrument. The former has questions that require information about the respondents’ gender, age, fields of study, number of years studying, number of subjects related to English, and number of hours dedicated to learning English. The latter is composed of 78 statements that pertain to the three domains of attitude: cognitive, behavioral, and emotional. Each domain is further divided into two categories as shown in Table 1.

The value of Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.886 which shows an acceptable consistency of reliability of the instrument.

Procedure

The development of the research consisted of three stages: the development of the instrument, the application of the instrument, and the analysis of the data. First, several questionnaires were studied and analyzed in order to choose the most appropriate ones for the purposes of the current research; the criteria to select the instruments were (a) acceptable value of Cronbach’s Alpha, (b) similarity with the Chilean reality, and (c) Chilean context. After the analysis of the collected instruments, three previous investigations were considered (see Gómez Burgos & Pérez Pérez, 2015; Soleimani & Hanafi, 2013; Tahaineh & Daana, 2013). Later, the instrument was designed and sent to three professors to corroborate its validity; it was also piloted with ten students randomly selected from the target population. Then, all comments were considered and the final version of the instrument was presented. As a second stage, the questionnaire was sent to students of five different universities in the south of Chile by email with an invitation to participate. The first answer was received on 10/23/2016 and the last answer was recorded on 12/22/2016; the questionnaire was available from October until the end of December 2016. Finally, the responses to the questionnaire were analyzed using the statistical program SPSS.

Results

The most important results will be discussed in terms of the distribution of frequencies and percentages, the total means value, the standard deviation for each domain, and the results of the non-parametric test Mann-Whitney-U Test.

Cognitive Domain

The cognitive domain of attitudes is represented by 30 statements. The results of the domain are represented in Table 2.

Table 2 Results of Cognitive Domain

| Item # | Frequency (percentage) | Means | Std Dev | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Disagree | |||

| Sub-category: English as a Universal Language | ||||

| 1 | 40 (43%) | 53 (57%) | 2.779 | 1.2967 |

| 4 | 100 (90%) | 11 (10%) | 3.985 | .9686 |

| 7 | 124 (99%) | 1 (1%) | 4.649 | .6067 |

| 10 | 117 (96%) | 5 (4%) | 4.389 | .8093 |

| 13 | 121 (98%) | 2 (2%) | 4.588 | .7111 |

| 17 | 43 (51%) | 41 (49%) | 3.031 | 1.1763 |

| 20 | 84 (86%) | 14 (14%) | 3.779 | 1.0546 |

| 22 | 106 (92%) | 9 (8%) | 4.229 | 1.0120 |

| 24 | 87 (86%) | 14 (14%) | 3.824 | 1.0847 |

| Sub-category: English at the University and Academic Purposes | ||||

| 26 | 55 (56%) | 43 (44%) | 3.115 | 1.2443 |

| 27 | 63 (71%) | 26 (29%) | 3.389 | 1.0639 |

| 31 | 67 (66%) | 34 (34%) | 3.351 | 1.2085 |

| 32 | 74 (82%) | 16 (18%) | 3.588 | 1.0067 |

| 36 | 83 (76%) | 26 (24%) | 3.740 | 1.3450 |

| 37 | 109 (92%) | 10 (8%) | 4.160 | 1.0511 |

| 41 | 76 (82%) | 17 (18%) | 3.603 | .9975 |

| 42 | 79 (64%) | 24 (36%) | 3.481 | 1.0767 |

| 46 | 75 (82%) | 17 (18%) | 3.611 | 1.0566 |

| 47 | 62 (70%) | 27 (30%) | 3.397 | 1.1548 |

| 51 | 29 (29%) | 72 (71%) | 2.557 | 1.2351 |

| 52 | 99 (92%) | 9 (8%) | 4.000 | .9282 |

| 56 | 13 (14%) | 80 (86%) | 2.267 | 1.0139 |

| 57 | 38 (37%) | 66 (63%) | 2.618 | 1.3270 |

| 61 | 35 (34%) | 69 (66%) | 2.534 | 1.3773 |

| 62 | 31 (34%) | 61 (66%) | 2.405 | 1.3114 |

| 66 | 64 (65%) | 34 (35%) | 3.221 | 1.1916 |

| 67 | 66 (63%) | 38 (37%) | 3.252 | 1.2238 |

| 71 | 86 (84%) | 16 (16%) | 3.939 | 1.2010 |

| 72 | 19 (17%) | 95 (83%) | 1.924 | 1.2380 |

| 76 | 96 (88%) | 13 (12%) | 3.985 | .9844 |

Figures in Table 2 show that the average of the participants in agreement regarding the 30 statements of the cognitive domain of attitude was 68% against 32% of the respondents who disagreed. However, when the analysis is conducted by sub-categories in the same domain, the classification English as a Universal Language evidenced an average of 82% in agreement with the nine statements of that group in comparison to the category English at the University and Academic Purposes that showed only 62% in agreement.

Item 7 of the survey (“The English language is a really helpful tool for the future prospects of any professional”) obtained the highest level of agreement among the participants with 99% of positive preferences, while Item 17 (“People who study English for a longer time have wider general knowledge”) was the lowest score with 51% in agreement on the positive side. Other remarkable items of the domain are Item 13 (“Speaking English opens work opportunities”) that garnered 98% of positive preferences and Item 10 (“Speaking English allows communication with people from all over the world”) where the percentage of positive attitude was 96%, among others.

Behavioral Domain

The behavioral domain of attitude is represented by 20 statements. The most significant results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Results of Behavioral Domain

| Item # | Frequency (percentage) | Means | Std Dev | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Disagree | |||

| Sub-category: English at Home and Leisure | ||||

| 3 | 7 (6%) | 101 (94%) | 1.779 | .9710 |

| 6 | 47 (47%) | 52 (53%) | 2.992 | 1.2800 |

| 9 | 35 (36%) | 61 (64%) | 2.634 | 1.2166 |

| 12 | 87 (82%) | 19 (18%) | 3.786 | 1.1702 |

| 15 | 33 (34%) | 63 (66%) | 2.687 | 1.2221 |

| 16 | 25 (23%) | 84 (77%) | 2.198 | 1.3268 |

| 19 | 93 (86%) | 15 (14%) | 4.053 | 1.1523 |

| 21 | 18 (20%) | 74 (80%) | 2.344 | 1.1147 |

| 23 | 36 (36%) | 64 (64%) | 2.656 | 1.2075 |

| 25 | 54 (52%) | 49 (48%) | 3.076 | 1.3337 |

| Sub-category: English at the University and Academic Purposes | ||||

| 30 | 59 (59%) | 41 (41%) | 3.168 | 1.2719 |

| 35 | 31 (30%) | 71 (70%) | 2.542 | 1.1849 |

| 40 | 26 (23%) | 88 (77%) | 2.183 | 1.3405 |

| 45 | 16 (13%) | 109 (87%) | 1.695 | 1.1087 |

| 50 | 76 (87%) | 11 (13%) | 3.702 | .9663 |

| 55 | 33 (31%) | 72 (69%) | 2.511 | 1.3380 |

| 60 | 37 (36%) | 66 (64%) | 2.641 | 1.3131 |

| 65 | 43 (45%) | 52 (55%) | 2.908 | 1.1796 |

| 70 | 45 (46%) | 53 (54%) | 3.000 | 1.2950 |

| 75 | 18 (17%) | 86 (83%) | 2.084 | 1.1769 |

Table 3 reveals that an average of 40.5% of the participants agreed on the statements of the behavioral domain in contrast to 59.6% of participants who marked disagreement on the 20 statements as an average. Regarding Sub-category 1 (English at Home and Leisure) the average percentage of agreement was 42%, while in Sub-category 2 (English at the University and Academic Purposes) the average was 39%.

When analyzing specific items in the behavioral domain of attitude, four statements obtained an average of more than 80% of choices that reflected positive attitude towards the assertions. On the one hand, Item 45 (“I do not pay attention when my English teacher explains contents”) showed that 87% disagreed with the statement, that is, participants demonstrated a positive attitude towards the assertion. Item 50 (“I attend English lessons eager to learn”) ranked an average of 87% as well regarding positive preferences. On the other hand, Item 3 (“I have a fixed schedule at home to study English”) indicated that 94% of the contestants disagreed with the statement.

Emotional Domain

The emotional domain of attitude was represented by 28 assertions. Table 4 shows the main results.

Table 4 Results of Emotional Domain

| Item # | Frequency (percentage) | Means | Std Dev | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Disagree | |||

| Sub-category: English as a Universal Language | ||||

| 2 | 73 (77%) | 22 (23%) | 3.603 | 1.1141 |

| 5 | 108 (95%) | 6 (5%) | 4.252 | .8801 |

| 8 | 14 (12%) | 106 (88%) | 1.672 | 1.0410 |

| 11 | 77 (81%) | 18 (19%) | 3.687 | 1.1374 |

| 14 | 106 (94%) | 7 (6%) | 4.137 | .9262 |

| 18 | 12 (10%) | 108 (90%) | 1.672 | 1.0630 |

| Sub-category: English at the University and Academic Purposes | ||||

| 28 | 91 (83%) | 19 (17%) | 3.855 | 1.1840 |

| 29 | 84 (88%) | 12 (13%) | 3.863 | 1.0360 |

| 33 | 109 (95%) | 6 (5%) | 4.244 | .8952 |

| 34 | 96 (88%) | 13 (12%) | 3.939 | 1.0937 |

| 38 | 39 (41%) | 57 (59%) | 2.756 | 1.2655 |

| 39 | 63 (68%) | 29 (32%) | 3.321 | 1.1386 |

| 43 | 68 (73%) | 25 (27%) | 3.511 | 1.1527 |

| 44 | 82 (82%) | 18 (18%) | 3.748 | 1.1459 |

| 48 | 32 (28%) | 83 (72%) | 2.244 | 1.4681 |

| 49 | 20 (18%) | 92 (82%) | 2.099 | 1.2144 |

| 53 | 49 (54%) | 41 (46%) | 3.115 | 1.1207 |

| 54 | 29 (28%) | 74 (72%) | 2.473 | 1.1788 |

| 58 | 85 (86%) | 14 (14%) | 3.794 | 1.0577 |

| 59 | 69 (63%) | 26 (27%) | 3.519 | 1.2791 |

| 63 | 65 (70%) | 43 (40%) | 3.221 | 1.4158 |

| 64 | 13 (12%) | 94 (88%) | 1.893 | 1.1180 |

| 68 | 107 (96%) | 4 (4%) | 4.229 | .8187 |

| 69 | 122 (98%) | 3 (2%) | 4.611 | .6858 |

| 73 | 51 (51%) | 49 (49%) | 2.947 | 1.2546 |

| 74 | 21 (21%) | 80 (79%) | 2.191 | 1.2897 |

| 77 | 21 (19%) | 89 (81%) | 2.137 | 1.2635 |

| 78 | 83 (86%) | 13 (14%) | 3.817 | 1.1149 |

In the emotional component of attitudes, the general average percentage of agreement was 61.2%. The highest average of agreement for this group was obtained on Item 69 (“I would like to express myself in English more fluently”) with 98% of preferences whereas the lowest score was from Item 49 (“Honestly, I am not very interested in English lessons”) which showed a positive attitude with 82% disagreement with the statement, followed closely by Item 77 (“I prefer to learn English the way I was taught in secondary school”) which ranked 19% in agreement.

If the analysis is conducted per sub-category, the first one, English as a Universal Language obtained a 62% average of agreement and the second category, English at the University and Academic Purposes, achieved 61% of preferences. However, the analysis per specific items shows that six assertions obtained more than 90% average of preferences; for example, Item 68 (“I like perceiving that I am learning English”) was marked 96% as the average of agreement; similar to Items 5 (“English is the most highly regarded language socially”) and 33 (“I like feeling that I am making progress in English”) that obtained a 95% average of preferences.

Finally, the Mann-Whitney U test was run in order to compare male and female participants’ attitudes. Based on the results obtained, it was evidenced that there was no significant difference between the two groups, that is, subjects reported similar answers to the statements of the questionnaire. The results of the three components of attitudes, according to the Mann-Whitney U test are shown in Table 5.

Table 5 Results of Mann-Whitney U Test

| Attitudes | Cognitive Component | Behavioral Component | Emotional Component | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mann-Whitney U | 1930.429 | 1897.533 | 1912.300 | 1978.625 |

| Wilcoxon W | 4183.353 | 4166.533 | 4159.300 | 4218.554 |

| Z | -1.023 | -1.187 | -1.0958 | -0.7951786 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.445 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.53 |

From this data, we can conclude that the attitude among male and female participants is the same as the p-value, which was higher than the level of significance (0.445 > 0.05), meaning that there was no significant difference between male and female students. Meanwhile, the results show that the three specific components of attitude had slight differences as the cognitive component obtained less value than the behavioral and the emotional ones.

Conclusions and Implications

The current study aimed at investigating undergraduate students’ attitudes towards EFL in university contexts in Chile. The findings evidenced that 131 students hold highly positive attitudes regarding EFL at the tertiary level in Chile. The cognitive aspect of attitude towards English showed evidence of the highest mean score while the behavioral domain of attitude in our study represented the lowest mean score; similar to what was reported by Soleimani and Hanafi (2013). This study showed that attitudes have a very precise influence on learners’ behavior, similar to what Gómez Burgos and Pérez Pérez (2015) reported in their work. A positive attitude towards a foreign language is fundamental to learning it (Fakeye, 2010; Hashwani, 2008; Lai & Aksornjarung, 2018; Zainol et al., 2012) because it allows learners to have a favorable predisposition towards its learning (Karahan, 2007). However, there was statistically no significant difference between male and female students after applying the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test.

With respect to the cognitive aspect of attitude, this study showed that this domain was extremely well accepted by the participants; both sub-categories obtained the highest percentage of agreement, especially the sub-domain English as a Universal Language, which ranked as having the greatest value of the study. This is aligned to the idea of English as an international language (Pennycook, 1994) and the participants’ awareness of the importance of English as a global language as reported by Puerto Zabala and Reyes Vargas (2014) and Asghar, Jamil, Iqbal, and Yasmin (2018). Similarly, respondents ascertained that learning English is a specific resource that gives power, as previously alleged by Matear (2008).

In regard to the behavioral and emotional aspect of attitude, the findings in this category are aligned with the reports given by Asghar et al. (2018) and Puerto Zabala and Reyes Vargas (2014), among others, due to the learners’ positive attitude towards these components in spite of the lower results obtained in the behavioral aspect. In this domain, the sub-group English at the University and Academic Purposes obtained negative approval by the respondents because the group was related to the participants’ own responses and behavior towards the English lessons and their study habits. Based on the responses, the learners are keen about learning English and they attend the lesson enthusiastically, but they do not pay enough attention to their instructors and they are embarrassed about speaking in class. Even though the students wish to be part of the international English-speaking community, they might find themselves trapped by their own time-consuming university obligations, which interfere with more constant practice and study of the language prior to the lessons (Kormos et al., 2011). Evidently, there are a number of factors, other than lack of time, that make an impact on the level of students’ participation and involvement in the English lessons: attitudes towards the language, anxiety, or fear of ridicule. As an additional component, even if English is generally perceived as a very important skill to be acquired at some point in their professional training, the perception of English as a subject is usually regarded as less important than the core modules for each program. This might help explain this apparent nonchalant attitude towards the lessons.

With reference to the emotional aspect, learners showed their interest in learning English as presented by Asghar et al. (2018); data also revealed that learners like English and those who speak it, similar to the report of Al-Mamun et al. (2012).

This study might contribute to complement research in the field of EFL in Chile as “there is a lack of research in the area of affective factors that influence the learning of the target language, especially the role of positive or favorable attitudes that students hold in different classrooms” (Gómez Burgos & Pérez Pérez, 2015, p. 323). In this line, the current study contributes to complement the information available of the Chilean learner specially in the area of the learners’ opinions towards the foreign language in tertiary programs. Participants of this investigation alleged that they would like for the teaching of English to become a priority in Chile (94% agreement with the assertion) and suggest this be considered by the national authorities when deciding on the new policies related to the inclusion of the foreign language in the country. These findings can be used to complement pertinent public policies in Chile in order to promote the inclusion of English in the country.

As to the implications offered by this study and the analysis of its results, it can be affirmed that this piece of research seeks to open a new path for EFL research in tertiary education in Latin America, particularly in Chile where, as reported by Barahona (2015), research lines in EFL settings correspond to “teachers’ beliefs, the practicum, identity formation, teacher’s perception of their own practices, teacher mentors and pre-service teacher relationships and teachers’ metacognitive knowledge” (p. 8). Therefore, it is to be concluded that a study on the university learners’ side of the spectrum, more specifically, about their attitudes towards EFL, is an underdeveloped topic that might lead to interesting findings to widen the field of EFL research in Chile.

The institutions included private and public spheres, and the wide age range of the participating students shedding light on the importance of investigating how a relevant affective factor-attitude-might impact the acquisition of a foreign language in university students from all sorts of origins, making this issue a transversal one. Placing more emphasis on areas like English for specific purposes (ESP) in university programs offers more opportunities for undergraduate students to merge their fields of expertise with a second language, which has proven to trigger positive attitudes towards its acquisition.

In order to achieve this goal, it would be necessary to introduce some changes in the way English is taught in tertiary education. These changes should cover aspects such as syllabi design, the training of teachers to provide challenging yet attainable ESP lessons at university level, and the consideration for students’ needs when designing courses via survey application, to name a few. This way, teachers will ensure that tasks and practical activities promote the use of the target language for professional and academic purposes in a sheltered environment, where students feel comfortable while producing English. The combination of these factors would undoubtedly heighten affective factors such as motivation and positive attitudes towards the language, since the students will relate to the contents studied, while knowing they will be able to use English in practical ways for their future careers.

As for the limitations of the study, the number of participants (131 undergraduate students), and the number of participating institutions (4) might be seen as a drawback as they are from only one region in the south of the country. Accordingly, the study could be expanded to other regions of Chile so as to have a wider variety of participants and, therefore, an assortment of institutions. A wider sample of students and institutions might in turn provide additional variables to consider, such as socio-economic backgrounds, types of programs, and geographic location, all of which can enlarge the scope of the present study.

With that in mind, there would be an in-depth study and analysis of the Chilean reality in this matter. A final aspect to consider has to do with the limited evidence reported from studies conducted in this particular field of language teaching, specifically in tertiary education. As this work is a pioneer in the area, there are no standards or literature with which to compare these outcomes. Nonetheless, it opens a new avenue for expanding research in EFL in Chilean contexts.