Introduction

Language assessment literacy (henceforth LAL) is an area of ongoing debate in the field of language testing. The research on this topic has focused on the components of LAL (Davies, 2008; Inbar-Lourie, 2013b), models for describing LAL (Giraldo, 2018b; Malone, 2017), definitions (Fulcher, 2012), and the shape of this construct across different stakeholders (Pill & Harding, 2013; Taylor, 2013). In essence, LAL represents the different levels of knowledge, skills, and principles required to engage in language assessment, either from a development perspective (i.e., designing and evaluating language assessments) or from a knowledge perspective, that is, understanding and using scores from assessments to make decisions about people’s language ability.

Much research, especially when it comes to language teachers, has not used the term LAL explicitly but has clearly studied areas that deal with language assessment in practice. For example, various research studies have examined what teachers do in the classroom for language assessment (Hill & McNamara, 2011; Rea-Dickins, 2001), what they think about language assessment, that is, their beliefs (Díaz, Alarcón, & Ortiz, 2012; López & Bernal, 2009), and the instruments they use for collecting information about students’ language ability (Cheng, Rogers, & Hu, 2004; Frodden, Restrepo, & Maturana, 2004; Tsagari & Vogt, 2017). Thus, it can be argued now that LAL has solidified as a general research and conceptual framework to scrutinize the meaning, scope, and depth of this construct in language testing in its three overarching components (Davies, 2008): knowledge, skills, and principles for language assessment.

A clear trend in the research has been the prominent use of psychometric measures to research LAL. Specifically, scholars have used questionnaires to study LAL as it reflects content from language testing courses (J. D. Brown & Bailey, 2008; Jin, 2010; Lam, 2015) and, in the case of language teachers, their training in LAL, current level of LAL, and needs to further their understanding of language assessment (see specifically Fulcher, 2012; Vogt & Tsagari, 2014). Given statistical interpretations, data from questionnaires can be used to sensibly derive generalizations about populations (i.e., language teachers), as the data can describe extensive aspects of LAL, including terminology and technicalities of test design. On the other hand, few studies have used a mixed-methods approach (Tsagari & Vogt, 2017) to further understand, now in depth, what LAL means for language teachers. Although quantitative and mixed-methods studies have indeed yielded useful results to conceptualize LAL, further research is needed to capture other areas of language teachers’ LAL and, therefore, provide a more valid account of what this construct means for this population.

My purpose with this article, then, is to reflect on the need to have a broader perspective towards researching the LAL of language teachers. To do so, I first explain why the focus on language teachers’ LAL is necessary and then review current research challenges surrounding LAL. Lastly, I put forward two major proposals within a post-positivist research paradigm: the need to expand LAL constructs and a related need to expand research methodologies.

Why a Focus on Language Teachers’ LAL?

Taylor (2013) explained four differential profiles of stakeholders in language assessment: test writers, classroom teachers, university administrators, and professional language testers. The author argues that these people should have different levels of knowledge, skills, and principles for doing language assessment. Such levels refer to aspects including knowledge of theory, technical skills, principles and concepts, language pedagogy, sociocultural aspects, and others. In general, the call that Taylor makes is to conduct research to examine her proposal so that the field can increase its awareness of LAL among these stakeholders.

While research for these different profiles is welcomed, language teachers have remained a central stakeholder group, arguably because they are the ones more directly engaged in doing language assessment (Giraldo, 2018b; Tsagari & Vogt, 2017). The research and discussions about language teachers’ LAL has given two central trends. On the one hand, teachers are expected to possess quite a wide array of knowledge, skills, and principles, as several authors have emphasized (Fulcher, 2012; Giraldo, 2018b; Inbar-Lourie, 2013a; Stabler-Havener, 2018). On the other hand, research has consistently shown that pre- and in-service language teachers need and want training across the board (Fulcher, 2012; Giraldo & Murcia, 2018; Vogt & Tsagari, 2014). Additionally, current studies have started to shed light on the complexity of LAL in its sociocultural milieu, that is, language teachers’ institutional contexts of assessment (Hill, 2017; Scarino, 2013; Sultana, 2019). For example, in Sultana (2019) one of the language teachers stated the following when asked about a public examination:

Does it matter? Public examination is a public examination. It does not matter what I think, my duty is to prepare the students for the examination. (p. 10)

The excerpt above attests to the fact that the sociocultural context of language teachers shapes and even constrains their LAL (Inbar-Lourie, 2012, 2017a). Thus, the research arena in LAL, and this includes language teachers of course, is going through a process of exploration and refinement (Inbar-Lourie, 2017b). In regard to language teachers, it can be argued that their LAL involves three moments for scrutiny: the before, the now, and the after. The before in LAL refers to teachers’ prior training (or lack thereof) in language assessment. The now refers to language teachers’ current practice in language assessment and what this process implies. Finally, the after includes the level of LAL growth once teachers have finished professional development experiences in LAL; this focus includes their perceived improvement in LAL and how they put new learning into practice. In synthesis, the LAL of language teachers should be carefully studied for the following four reasons:

They are the ones most directly engaged in planning, implementing, and interpreting language assessments, with the corresponding responsibility to gauge students’ level of language ability.

The consensus in the field of language testing is that, for the previous point to be well done, language teachers need adequate levels of LAL.

A related point is that language teachers have reported the need to improve their LAL in general, for which an understanding of their life-worlds is a central condition (Hill, 2017; Scarino, 2013).

Discussions of LAL need to center on teachers’ LAL development (Baker & Riches, 2017) and how this development occurs through time.

Challenges in Researching Teachers’ LAL: From Constructs to Instruments

Although numerous articles exist defining what LAL is, the field of language testing has not ultimately reached a consensus as to what the construct means at the granularity level. Thus, a first challenge in researching LAL is trying to operationalize what it means (Inbar-Lourie, 2013a): There is no solidified, agreed upon knowledge base. However, this is not necessarily a negative aspect of LAL-in reality, it invites further research. The complexity lies in how to operationalize the construct for research purposes.

Another related challenge is to identify who the authorities are for establishing the aforementioned knowledge base. Stabler-Havener (2018) argues that a group of scholars should come forward and formulate ways to define what LAL means and implies, specifically, for language teachers. Efforts to provide broad guidelines in language testing exist; for instance, the guidelines for practice and code of ethics by the International Language Testing Association (2000, 2007). This association was formed by scholars in language testing, and their documentation is generally taken as sound. In the case of defining LAL, however, there still is not an established body of thinkers willing to define it.

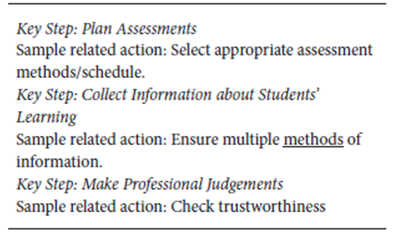

As briefly commented on earlier, language teachers’ LAL is complex, so another challenge in researching this construct is to manageably state where the concept stands for this stakeholder group. To illustrate, the works by Davison and Leung (2009) and Hill and McNamara (2011) have provided thick descriptions of what teachers do and why they do so in classroom language assessment. In Davison and Leung (2009), the authors describe what they call “key steps in teacher-based assessment” (p. 396), some examples of which are shown in Table 1.

The actions in Table 1 can be conceptualized against the overarching components of LAL, that is, knowledge, skills, and principles. Selecting appropriate methods, for example, requires knowledge of assessment instruments so they are fit-for-purpose; the use of varied methods for assessment may require skills in design, administration, and evaluation. Finally, checking whether an assessment can be trusted reflects back on principles for doing sound assessment; specifically, an instrument whose information cannot be trusted may lead to unfair practices.

In conclusion, the LAL of language teachers embodies what is a potentially large set of knowledge, skills, and principles. For example, in Giraldo (2018b), readers can find 66 descriptors that seek to explain part of the LAL for language teachers in eight dimensions: awareness of applied linguistics, awareness of theory and concepts, awareness of one’s own language assessment context; instructional skills; design skills for language assessments; skills in educational measurement; technological skills; and awareness of and actions towards critical issues in language assessment. Additionally, as it has come to be accepted, language teachers’ contexts of assessment are one more ingredient in the LAL puzzle. Scarino (2013, 2017) has been emphatic in explaining that efforts to cultivate LAL among teachers should include acknowledgement of their life-worlds, or interpretive frameworks, where their beliefs, values, experiences, and contextual knowledge play a role in LAL.

A last challenge in this review refers to the use of questionnaires for researching LAL. As stated elsewhere, questionnaires can compile large amounts of data on varied topics of LAL, which can then be used to interpret trends in the construct. However, these instruments come with their own limitations when researching teachers’ LAL, some of which are internal to the field and others which relate to the use of questionnaires in general, as I discuss next.

Fulcher (2012) explained that the use of a survey in his study led to two problematic issues, namely, low variation in responses and the idea that teachers need to improve LAL across the board. The answers in this survey suggested that they thought “all topics within language testing are important” (Fulcher, 2012, p. 127) and needed for training. As Fulcher states, the fact that the respondents were self-selected may account for this result. This sentiment is also observed in the studies by Vogt and Tsagari (2014) and Yan, Fan, and Zhang (2017) with in-service teachers in Europe and China respectively; and Giraldo and Murcia (2018) with pre-service teachers in Colombia. The results then beg the question of whether these teachers do indeed think all of the items they see in questionnaires are truly important for their LAL. Further, Giraldo and Murcia warn that the use of pre-determined questionnaires needs to be examined carefully. In their study, the researchers used the survey developed by Fulcher and then realized it lacked a more fine-grained definition of classroom-based assessment, where issues such as portfolio use were not included.

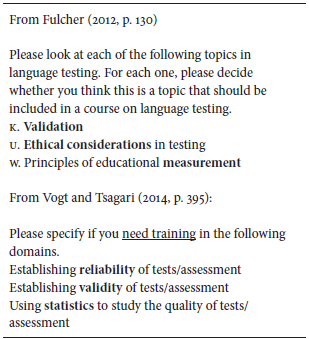

One last internal limitation that I see in the use of questionnaires to tap into language teachers’ LAL is the use of technical jargon. To illustrate, validity in language testing and in other fields (e.g., psychology) traditionally has represented the degree to which an assessment instrument measures what it is supposed to measure and nothing else (H. D. Brown & Abeywickrama, 2010). However, it can be ascertained with confidence that this is no longer an accurate definition in language testing, which has embraced Messick’s (1989) view on the matter. So, in a survey where language teachers select validity as a concept (in fact quite a far-reaching and ongoing debate) to learn about in language assessment, some may not be aware of what the term actually implies. In other words, how can I know that something is important (or that I need training in it) if I am not sure what that something really is? Or perhaps my definition may be inappropriate or incomplete. Table 2 includes sample items from two different questionnaires for researching the LAL of language teachers. The items refer to long-standing debates in language testing and require, to my belief, a good deal of knowledge to understand them. I have highlighted them in bold and made minor modifications to the format of the original questionnaires.

Lastly, Dörnyei and Taguchi (2010) warn practitioners of the possible disadvantages of using questionnaires, among which they explain the superficiality of answers, unreliable answers, and low levels of literacy, which the authors define as reading and writing; as the present paper implies, low levels of LAL may affect respondents’ answers and their validity. Additionally, the authors comment on social desirability (wanting to choose answers to please the researcher), self-deception (respondents deviating from what is true about them), and acquiescence bias, or what they call “yeasayers” (p. 9) who would agree with items that look right at face value. Finally, Dörnyei and Taguchi warn of fatigue effects, which can have a negative impact on the last items in a questionnaire.

To reiterate, questionnaires have been useful in researching LAL as they have allowed the field to operationalize this construct across different stakeholders. However, given the complexity of language teachers’ LAL, complementary approaches to research should be welcomed so that the field delves into the intricacies of the matter. To such end, I now move on to suggesting possible expansions of LAL research.

A Post-Positivist and Interpretive Philosophy for Studying Teachers’ LAL

The reflection I am proposing is grounded on a general research philosophy. Positivist approaches to research see nature as measurable, easily observable, and quantifiable (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007). Conversely, a post-positivist approach sees reality as amenable to varied interpretations where probabilities, rather than absolute truths, are sought and understood (Guest, Namey, & Mitchell, 2013). Particularly in LAL, a post-positivist view to research embraces teachers’ LAL as situated practice. Hill (2017), for example, argues that a precondition for teachers’ LAL is a close examination of the contexts where they do assessment, what Scarino (2013) calls their interpretive frameworks or life-worlds. The implication for post-positivist research is that LAL research must look at language teachers’ reality in naturalistic contexts (Cohen et al., 2007).

Such research philosophy can have the advantage of listening to teachers’ voices regarding their LAL. As Inbar-Lourie (2017a) argues, their voices need “to be heard loud and clear” (p. 268), as this attitude can help to unveil the complexities of LAL for these stakeholders. A positivist view would not be fit for such purpose-it is not its intention, really-but a post-positivist view can be.

In test-based teaching countries such as those reported in Sultana (2019) and Baker and Riches (2017), a post-positivist and interpretive lens helped these researchers to realize that LAL is shaped by teachers’ cultures. Specifically, teachers can at times accept large-scale tests unquestioningly (Sultana, 2019), an issue Vogt and Tsagari (2014) see as problematic. Thanks to a post-positivist philosophy to LAL research, these problematic areas arise.

Expanding Research Constructs of Teachers’ LAL

As indicated, studies using questionnaires have provided insights into language teachers’ reported knowledge of and needs in LAL. Data from these studies tap into the before (i.e., prior training in LAL) and the now (their current needs). One expansion of the LAL construct that emerged as unexpected in Giraldo and Murcia (2018) was to elicit information about local policies for general assessment. In these authors’ study, the open-ended items in the survey made it clear that the different stakeholders who responded wanted to know about general policies for assessment in Colombia, or what is known as the “decreto 1290” (decree 1290) (Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia, 2009). This decree explains in depth how assessment both of and for learning is to be done in the general curriculum in elementary and high schools in this country. Therefore, this might be an area of language teachers’ LAL that needs to be further examined, especially because teachers are expected to balance these general policies as well as the internal technicalities of language testing. Authors have indeed highlighted that this coexistence can entail tensions teachers face in doing language assessment (Firoozi, Razavipour, & Ahmadi, 2019; Inbar-Lourie, 2008; Scarino, 2013, 2017).

Another expansion of the construct, and one that is slowly but steadily gaining momentum in LAL research, is language teachers’ interpretive frameworks for assessment (Hill, 2017; Scarino, 2013, 2017). Specifically, qualitative research has studied language teachers’ LAL as operationalized in their practices and beliefs, or what I call the now in LAL. These studies have consistently suggested an overreliance on the use of traditional methods such as tests and quizzes that reflect external examinations (Cheng et al., 2004; Frodden et al., 2004; López & Bernal, 2009; Sultana, 2019; Tsagari & Vogt, 2017). In terms of beliefs, the more trained in LAL teachers are, as suggested by the research, the more they believe language assessment should be used for formative purposes (López & Bernal, 2009). Contrarily, when training in LAL is lacking, teachers believe assessment is an artefact of power and control, a criticized misuse of tests (Fulcher, 2010; Shohamy, 2001).

In order to further comprehend these two aspects of the LAL construct (practices and beliefs), qualitative research should be conducted on the relationship between language assessment and policies for general assessment. For instance, in Colombia, it might be enlightening to know how language teachers in schools use the decree 1290 for their particular assessment practices and what they think about it. In a related manner, research can ask teachers about how they design an assessment in its general universe. To illustrate, an assessment can align with a school curriculum and modality (e.g., tourism), students’ ages and interests, a school’s general philosophy of language learning (e.g., communicative), standards for language learning, and can follow national guidelines (e.g., be mostly formative, as decree 1290 suggests). In other words, research can be conducted on what institutional and social forces shape language teachers’ design of assessment instruments and whether or not there is harmony or tension in this relationship.

Lastly, and as López and Bernal (2009) warn, the validity of teacher-designed assessments and the consequences that unfold from these instruments need to be studied. The authors connect these two issues to ethics. Thus, if at all possible, uses and misuses (e.g., using assessments to control misbehavior) of assessments, and the reasons for them to happen, should be elicited in qualitative research on LAL. Although this may indeed pose ethical issues for the teachers themselves, unpeeling the opinion of language assessment at the grassroots level (i.e., the classroom) can be informative to foster our understanding of LAL. Of course, ethical considerations for this research, namely confidentiality, need to be crystal clear so participants can disclose the information they think is pertinent (Avineri, 2017).

An under-researched area in LAL is the impact that professional development initiatives have on language teachers’ LAL. Few studies have addressed how teacher learning increases thanks to programs that educate teachers in LAL. For example, Walters’ (2010) study helped ESL teachers in New York to become more critical towards the nature of standards for learning English, which the author argues is a part of having LAL. In the study by Nier, Donovan, and Malone (2009), teachers of less commonly taught languages became more aware of concepts and design in language assessment. In Arias, Maturana, and Restrepo (2012), the participating teachers made their assessments more comprehensive and valid; they also embedded democracy and fairness in their practice by making students active participants in assessment. Finally, in a recent article, Baker and Riches (2017) reported that Haitian language teachers-engaged in a one-week LAL program-learned how to create questions for reading comprehension, embed vocabulary in teaching and assessment tasks, and in general integrate language skills in assessments, make connections between teaching and assessment, and consider assessment as essentially student- and learning-centered.

Asking language teachers about professional development in LAL, as the studies above did, refers to what I call the now. The proposed expansion is to ask participants in these scenarios to express their perceptions of what works and what does not for increasing their LAL and how their LAL is changing thanks to these professional development programs. Additionally, research can be conducted to see whether LAL programs do in fact exercise change in teachers’ language assessment practices, what I call the after in the LAL construct; specifically, research could also evaluate the effectiveness of language testing courses for pre-service teachers, once they are doing their professional practice as in-service teachers.

A clear research gap concerns the lack of information as regards the education of pre-service teachers’ LAL, as Giraldo and Murcia (2018) pointed out. The authors invite teacher educators to share their experiences so other practitioners can benefit from the way LAL is taught at the pre-service education level, where professional education in LAL is expected (Herrera & Macías, 2015; López & Bernal, 2009). Every experience can be considered a case study, and as Moss (2005) argues, case studies should be done in the service of others. To conclude, the idea of researching language testing courses in language education programs reflects the need to empower training in LAL at the pre-service level, as Herrera and Macías (2015) argued.

Additionally, studying the characteristics of programs to foster language teachers’ LAL-both pre-service and in-service-can help the field to understand how teacher educators and teacher learners operationalize LAL. Classroom contexts are sociocultural in nature, due to the roles instructors and students have. Therefore, observational schemes may help to see how instructors actually teach the construct of LAL, what components they teach, what questions and discussions can emerge during lessons, what teacher learners bring to lessons (i.e., their interpretive frameworks), and how in the end teacher learners are familiarized with LAL at large. Taken together, data from case studies of this kind can help devise LAL initiatives elsewhere, by helping us to learn from other teacher educators’ successes and limitations. In Table 3, I summarize the proposed expansions in the construct of teachers’ LAL for research purposes.

Expanding Methodologies for Researching Teachers’ LAL

Expanding the research constructs for researching LAL necessitates the implementation of qualitative methodologies for data collection. They permit researchers to unearth the gist of language teachers’ LAL as qualitative research seeks the hows and whys to project them through thick descriptions of participants’ natural milieu (Mackey & Gass, 2005). This is something that quantitative methods are not meant to do.

Among the available methodological tools for qualitative studies on LAL, researchers can use interviews. They can help to deeply examine language assessment in practice in participants’ institutional contexts (Cheng & Wang 2007; Tsagari & Vogt, 2017). In particular, Tsagari and Vogt’s (2017) study helped them to confirm what they had identified in their previous quantitative study (Vogt & Tsagari, 2014): Teachers report low levels of LAL and need improvement in this area of their profession. Furthermore, interviews can unearth the overall power that tests can have on teachers and the way they teach (Shohamy, 2017), as the findings in Sultana (2019) show. Since interviews seek to elicit answers rather than give predetermined choices, teachers can provide insightful feedback for conceptualizing LAL. For example, in Giraldo’s (2019) case study, the teachers reported affective skills (e.g., giving feedback tactfully and “humanly”) as being part of their approach to assessment. Such a skill is not, to my knowledge, generally reported in discussions about LAL.

Another qualitative methodology for researching LAL is document analysis. Researchers can study the form and content of assessment instruments, as Frodden et al. (2004) and Giraldo (2018a) did; as stated elsewhere, these instruments can be compared and contrasted vis-à-vis the language learning documents existing in schools (e.g., language curricula); therefore, this comparative analysis can substantiate findings regarding to what degree language teachers integrate the assessment instruments they use or design with the forces that shape assessment.

Finally, observations can be used to describe and interpret how language assessment is done in language teachers’ classrooms, as Hill and McNamara (2011) reported. However, not only should observations be used to describe teachers’ practices but also characterize how professional development programs have affected teachers’ LAL. For example, observations can be done to see how teachers newly educated in the paradigm of alternative assessment actually put this knowledge in practice, a much-expected approach to language assessment (López & Bernal, 2009; Tsagari & Vogt, 2017). Additionally, observations can help to elucidate what happens in contexts where pre- and in-service teachers are being educated in LAL. Although research has reported successful outcomes of professional development initiatives (for example, Baker & Riches, 2017; Nier et al., 2009), the process of getting to such outcomes is not reported, therefore limiting the usefulness of these case studies to provide instructional insights for practice in other contexts.

Herrera and Macías (2015) propose a questionnaire to research the level of satisfaction that language teachers have regarding their LAL. However, the authors make it clear that qualitative methodologies are needed because “they will contribute to provide a portrayal of EFL teachers’ language assessment competences and needs” (p. 308). In synthesis, for researching LAL, qualitative approaches complement quantitative ones, and perhaps more importantly, have the potential to generate comprehensive data to increase the construct validity of researching the LAL of language teachers. In turn, this information can ignite follow-up discussions of LAL in the field of language testing.

Conclusions

The ongoing research on language teachers’ LAL has provided valuable insights into what they lack, need, do, and believe. Because this research has done so, the field of language testing is expanding its boundaries to invite new research paradigms to raise awareness of the construct, which may lead to what Inbar-Lourie (2017b) calls an era of language assessment literacies. My purpose in this paper was to propose ways in which the field’s invitation can be answered.

Language teachers are constantly making decisions about student learning based on data generated by assessments. Thus, they are a crucial stakeholder group for conducting comprehensive research on LAL, especially because research studies have suggested burning needs in teachers’ LAL. To have a more fine-grained picture of LAL for this group, I propose the use of a post-positivist and interpretive research philosophy to operationalize research constructs through qualitative methodologies. Specifically, the field can benefit from research studies on language teachers’ use of local policies for assessment, design of assessment instruments vis-à-vis these policies; uses and misuses of assessments; teacher perceptions towards professional development opportunities in LAL and their impact on teacher learning; the shape and impact of language testing courses on pre- and in-service teachers; and, overall, the impact of these programs once teachers are implementing new ideas and approaches to language assessment.

To tap into the aforementioned constructs, I suggest qualitative methods for data collection, including interviews, document analysis, and observations. Such research will not only listen to teachers’ situated LAL voices and their messages-loud and clear-but also use such data to further conceptualize LAL. The methods will also allow for a more complete, informative picture of the expanded research construct on LAL and, in turn, unveil the intricacies of the matter. Collectively, this information will be useful for practitioners (e.g., professional language testers, language teacher educators) to engineer approaches to support language teachers to improve their LAL, which will hopefully have a positive impact on student learning. That should be the ultimate goal of researching language teachers’ LAL.