Introduction

Living in a globalised world where there is a flux of people, economy, and knowledge, the need to carry out social, academic, and work-related activities has become apparent. This social phenomenon has significantly impacted on higher education institutions (HEIs) where practices, such as academic mobility, research, and the insertion to the labour market, are now required to be carried out and strengthened in order to meet international standards (Knight, 2010). To achieve this, the English language has played a key role in the internalisation of higher education because it is a tool which is used worldwide for communication and social relations (Romo López et al., 2005). Particularly, English is considered to be the means that promotes opportunities for university students to get jobs in the highly competitive labour market in political, economic, scientific, or academic fields.

Currently, Mexico is increasingly dependent on the growth of its manufacturing sector which has recently been challenged by external competition and gaps in the labour market. In response to these challenges, the Mexican government has undertaken massive investment in infrastructure and substantial reforms in education, including plans to increase the English proficiency of the Mexican population. Previously, having proficiency in the English language was not compulsory for graduates and professionals to get a job in the Mexican labour market. However, given the importance of English as an international language and the active role it plays in enabling Mexico to become a prominent contributor to the globalised world, English proficiency requirements have changed. Currently, having a strong academic background and high proficiency in English are key to finding jobs in the competitive Mexican labour market. The new graduates and professionals are now required to show evidence of at least a B2 or C1 proficiency level (according to the Common European Framework for Languages [CEFR]) to be considered for many jobs.

Despite the importance attributed to English as an international language, the General Director of the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness confirmed that only 5% of the Mexican population speaks and/or understands the language (Becerril, 2015). This limited English proficiency constitutes a particular threat to the manufacturing industry in Mexico because low English proficiency results in limited opportunities in the labour market for recent graduates (Navarro, 2006). The context of the present study, the University of Guanajuato, has seen limitations in the linguistic competence of students who graduate from the different BA programmes across the university. This is known by local employers from important industries who claim that they have noted limited English skills of recent graduates from this university, and that this frequently results in not hiring them because most of the vacant positions require high abilities to both produce and comprehend English.

In response to the above perceived limitations, two needs analysis (NA) cycles were conducted with four groups of stakeholders (i.e., heads of human resources in locally-based multinational companies, University of Guanajuato’s authorities and faculty members, language programme directors and teachers, and students from different BA programmes and disciplines) who took part in a series of focus groups and answered questionnaires between January 2018 and February 2019. The present study was guided by two research questions:

Background

In recent years, HEIs in Latin America have felt the need to promote English because it is an instrument which allows international communication, social and international relations, and the key to the local and international labour market. Therefore, these institutions have redirected their efforts towards preparing future professionals with not only disciplinary knowledge, but also skills in the foreign language. However, these efforts have been nuanced by limited flexibility, internationalisation, and technology platforms (Romo López et al., 2005); and old-fashioned teaching methods, low socioeconomic status of students, and large class sizes (Mora Vasquez et al., 2013) which have hindered effective English learning and thus expected language achievement in HEIs.

In Mexico, only a low percentage of the population speaks English (Navarro, 2006). In the University of Guanajuato, these limitations have been reformulated into challenges to promote English language education which is (a) of quality, (b) centred on the learner, and (c) based on institutional values with a view to strengthening the interplay between the English language and the liaison with the society. However, as previously mentioned, this university has seen limitations in the English competence of students who graduate from the different BA and BSc programmes. In this case, NA plays an important role in understanding the specific learning needs of students and the real expectations of the labour market regarding English language proficiency. However, this process has been greatly overlooked in this university, and has thus ignored ways through which English language achievement can significantly be enhanced.

Needs Analysis: An Overview

At this stage, it is important to define NA. In language education, NA can be defined as the process of identifying “what learners will be required to do with the foreign language in the target situation, and how learners might best master the target language during the period of training” (West, 1994, p. 1). In general, it is claimed that NA can be used for a wide range of purposes (Pushpanathan, 2013). For example, NA is believed to be useful for evaluating English programmes and, if necessary, changes can be implemented to match learners’ needs and language achievement. Richards (1990) alleges that NA is key to the planning of language courses and programmes. Some other benefits of conducting NA in language education is that it provides insights into learners’ and teachers’ perspectives, beliefs, and perceptions. This perceptual information can be used to adapt language programmes to the needs of learners, or to promote the acceptance of pedagogical changes or innovations among teachers (Pushpanathan, 2013). According to Pushpanathan (2013), the relevance of this process is that learners’ motivation and language achievement are enhanced when teaching and learning practices match their perceived and actual needs. In line with these benefits, Graves (1999) suggests that NA should be considered as a component in teacher training.

In general, NA is considered to be a fundamental component of English for specific purposes (ESP) (Robinson, 1991; West, 1994), because efforts are directed to connecting learners’ needs to communicative situations in function of what they are expected to perform in their discipline areas (Tudor, 1996). In this regard, it is commonly believed that NA is unnecessary for general English teaching and learning because learners’ needs in general English courses and programmes are hard to identify (Pushpanathan, 2013). However, there is a considerable number of scholars who advocate the use of NA for ESP or general English course design (Brown, 1995, 2009; Graves, 1999; Long, 2005; Richards, 2001; West, 1994; among others), because there is always a perceptible need of some kind which needs to be attended to (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987). In the same vein, Tudor (1996) argues that NA is necessary in general English courses and programmes because their content should be formulated and evaluated following an analysis of the communicative situations during which learners are expected to use the target language. This thus suggests that NA is an important set of tools which can be used for different teaching and learning purposes with a view to making language programmes more relevant to the real-life needs of learners (Pushpanathan, 2013).

In literature, several NA approaches have been suggested, depending on the language goals (for a detailed review of this frameworks, please refer to Hutchinson & Waters, 1987; Jordan, 1997; Robinson, 1991; among others). For the purpose of this study, a target situation analysis (TSA) model was used. For West (1994), this is the oldest approach to NA. It is widely known that this model was initially used by Munby (1978), when he introduced the processor which investigated learners’ needs, the so-called “communicative needs processor.” TSA can best be understood as an approach which explores needs which are further divided as “necessities,” “lacks,” and “wants” (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987). Elsaid Mohammed and Nur (2018) define necessities as “what students have to experience to perform in the target situation” (p. 53), lacks as “the gap between what students already know and what is needed in the target situation” (p. 53), and wants as “what students feel they need” (p. 53). The TSA model works to identify priorities regarding the target language, the preferred language skills, the functions to be developed, the activities, and the situation. In general, six questions are posed in this model: (a) the purposes of the target language, (b) how it is used, (c) its content, (d) who takes a role in the process, (e) the context, and (f) the time when the language will be used (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987).

As we have seen, NA may be useful for gathering information regarding attitudes, beliefs, and opinions. However, in order to ensure its effectiveness, it is necessary to examine and consider the contextual factors that play a role in processes of teaching and learning the target language. For this, all the stakeholders should participate in exploring the needs, and formulating the suggestions to address those needs. As we will see, this was the approach adopted in the NA cycles and the formulation of recommendations in the present study.

The Needs Analysis at the University of Guanajuato

The University of Guanajuato was the context of the present study. This state university is located in the Mexican State of Guanajuato and offers 153 programmes of different disciplines (from high school to the doctorate level) on four campuses. This HEI has departments in 14 cities throughout the State of Guanajuato. Depending on the discipline area, each BA and BSc programme requires students to take from four to eight semesters of general English courses. However, despite this requirement, the University of Guanajuato has seen limitations in the linguistic competence of students who graduate from the different BA programmes. Thus, following the claim that NA is an activity in which “the cycle of decision, data gathering, and data analysis repeats until further cycles are judged unnecessary” (McKillip, 1987, pp. 9-10), two NA cycles were conducted; the first one in January and February 2018, and the second one in February 2019.

For the purpose of this study, the TSA approach followed McKillip’s (1987) suggestions to conduct NA, as follows:

Step 1. Identification and description of users and purpose of NA. For this first step, the stakeholders in the processes of English teaching and language achievement at the University of Guanajuato were identified. Taking into consideration the perceived limitations concerning English proficiency at this university, the researcher formulated and then described the purpose of the NA cycles.

Step 2. Identification of needs. In this step, the language problems, needs, and challenges were explored and described. To do this, language teaching and learning discrepancies, that is, “problems . . . revealed by comparison of expectations with outcomes” (McKillip, 1987, p. 11), were mostly considered.

Step 3. Assessment of the importance of the needs. Once problems and their solutions were identified, the needs were then evaluated to promote the effectiveness of the prevailing general English programmes vis-à-vis future and present needs of students. To do this, three dimensions suggested by McKillip (1987) for evaluating solutions were considered:

Step 4. Communication of results. Finally, the results of the identification of needs and solutions were communicated to decisions makers, users, and other relevant stakeholders.

The Participants

According to McKillip (1987), stakeholders may have different perspectives on needs and solutions. Therefore, the two NA cycles were conducted with four groups of stakeholders (see Table 1). This decision enabled me to move away from outsiders’ to insiders’ views. (Long, 2005; Pushpanathan, 2013). Different means of communication (posters, Facebook posts, emails, formal letters, and radio spots) were used to call for participation. Information about the participants is detailed below.

Table 1 Participants of the Needs Analysis Stages

| Sessions | Participants | Cycle 1 | Cycle 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Employers from transnational companies | 5 | 4 |

| 2 | University authorities and decision-making entities | 36 | 17 |

| 3 | English language teachers | 31 | 25 |

| 4 | University students | 53 | 83 |

NA with employers. As a first step, two NA cycles were conducted with nine employers from several local transnational companies. In general, these first sessions with the employers were useful to understand their perspectives, needs, challenges, and expectations, and then communicate this information to the university community that attended the other rounds of sessions.

NA with university authorities. The second sessions were conducted with 36 university authorities in the first cycle, and 17 in the second cycle. The university authorities were the academic secretariat of the Guanajuato Campus, heads of divisions and departments, undergraduate and postgraduate programme coordinators, and other authorities involved in English teaching and learning in our university. The first part of this second round of sessions was conducted as a series of presentations in order to communicate the employers’ perspectives to the university authorities regarding expected language abilities of university students and graduates. Moreover, discussions were then initiated to understand the university authorities’ perspectives, needs, challenges, and expectations concerning English language achievement at the University of Guanajuato.

NA with English language teachers. The third sessions were conducted with 31 teachers in the first cycle of the NA process, and 25 teachers in the second cycle. These professionals teach English as a foreign language (EFL) to students from various disciplines at this university. As with the university authorities, the sessions with the EFL teachers started with presentations to communicate the results of the two previous sessions with employers and university authorities. After the presentations, group discussions with the EFL teachers were initiated to explore their perspectives regarding the learning and teaching of English at the University of Guanajuato, and to better understand their challenges in order to help them develop more effective language teaching and learning practices.

NA with university students. The last round of sessions was conducted with 53 university students in the first cycle, and 83 students in the second cycle from different BA programmes across the university. One of the primary objectives of these sessions was to communicate the results of the three previous rounds of sessions. Moreover, this session was intended to create a space where the students could communicate their perspectives and challenges regarding the learning of English at the University of Guanajuato with the purpose of understanding the limitations in their contexts and programmes to learn English. It also aimed at exploring their perspectives concerning more effective language learning practices which may improve their language proficiency.

The Instruments

In order to carry out NA, it is suggested that researchers use multiple instruments (McKillip, 1987). Scholars, such as Brown (1995, 2009), Long (2005), Richards (2001), Graves (1999), and West (1994), agree that questionnaires, observations, and (individual or focus group) interviews are instruments which can be used to explore needs. The benefit of combining multiple techniques is that it allows triangulation to produce credible and relevant results and solutions for the target population (Long, 2005).

As the main instrument during the NA cycles, focus groups were conducted with each group of stakeholders (see Table 1). In accordance with Gibbs (1997), focus groups enable participants to engage in group interactions during which individual as well as group views, attitudes, feelings, and beliefs are revealed. For this study, focus groups were necessary in order to explore the participants’ perspectives on expectations, needs, challenges, and suggestions regarding English language teaching and learning at the university with a view to formulating and informing solutions. In order to guide the discussions, questions and relevant topics concerning linguistic expectations and needs were used. The sessions in the two NA cycles were audio recorded. As a way to obtain more detailed information from the participants, paper-based questionnaires were designed and administered (please refer to Appendices A, B, C, and D). All the participants were informed of the objective of the project and their participation in it. They all expressed their consent to participate and formally provided it at the end of the questionnaires.

The data obtained from the recorded focus groups and questionnaires were transcribed completely. Once transcribed, the data were analysed using a thematic analysis which firstly involved identifying and demarcating extracts in which the participants voiced their expectations, needs, challenges, and suggestions regarding English achievement at the University of Guanajuato. Then, these perspectives were listed for the analysis. For the employers’ data, the extracts were selected and then categorised. For the university authorities’, English teachers’, and university students’ data, the extracts were identified and, based on their frequency, percentages of how many participants suggested the same idea were calculated to understand the importance attached to it.

The Results

In order to answer the first research questions (i.e., what are the stakeholders’ expectations, needs, challenges, and recommendations regarding English language achievement at the University of Guanajuato?), this section outlines the results of the focus groups and questionnaires that were used to explore the perspectives of the stakeholders from local companies and the university community. This section begins by presenting and discussing the results of the local employers’ perspectives concerning the challenges and needs that they face in their companies in terms of the English proficiency of the University of Guanajuato graduates and their suggested actions to enhance it. The section “University Authorities, English as a Foreign Language Teachers, and University Students” then presents and summarises the results of the discussions held during the sessions with university authorities, language teachers and students, as well as the questionnaires administered during these sessions.

The Employers

During the focus groups, all the employers agreed that their potential employees must demonstrate high English abilities to perform a range of activities in their companies, for example:

Extract 1. Employer 2’s Quotes

We are a global company. Therefore, we have to be in contact with people around the world using English.

Candidates have to demonstrate advanced proficiency skills in writing, speaking, listening, and reading.

Extract 2. Employer 5’s Quote

I would like for my employees to have proficient oral skills for efficient communication to be able to talk to clients and receive training. However, listening, writing, and reading are also relevant.

As can be seen in the above extracts, the employers emphasised the need for candidates or employees who have abilities to communicate and comprehend using English with high proficiency. When asked about the activities that need high English skills, the employers stated that from 80%-100% of the activities in their companies require English communication and/or comprehension. Some of the activities that they mentioned during the focus groups were:

oral and written communication (all the employers)

participation in problem-based business meetings (Employers 2 and 8)

persuasive writing (Employers 3, 5, and 9)

composition of business reports (Employers 1 and 5)

email composition (all the employers)

oral presentations (all the employers)

group discussions regarding projects and activities (all the employers)

interactions on the telephone (all the employers)

networking and negotiations in English with other companies/affiliates (all the employers)

problem-solving interactions in oral and written forms (all the employers)

in the case of the areas of accountancy and engineering, knowledge of principles, terms, and technical procedures and presentations (Employers 2, 3, and 7)

Again, this list shows that much of the communication that is expected from employees and candidates is in English for different purposes and activities. For example, as mentioned by Employer 4 (“for Japanese corporations, it is necessary to make reports to headquarters in Japan and USA”), interactions in some companies are held with Japanese people. As Japanese is not considered a global language, English becomes the lingua franca to establish communication among different executives. This in turn gives the knowledge of English a high value in those potential employees that they can hire.

However, when the employers were asked about whether graduates from the University are able to carry out those activities using English, they all expressed concerns about communication skills during work-related situations, for example:

Extract 3. Employer 1’s Quote

They [UG graduates] do not normally have a good command of spoken English.

Extract 4. Employer 3’s Quote

They [UG graduates] have an “acceptable” level of English, mainly in reading and writing, but not spoken. They are too shy because of their low confidence to speak it.

Extract 5. Employer 9’s Quote

There are not enough candidates who can satisfy the demands of the company.

As suggested in these extracts, the employers generally claim that graduates from the University of Guanajuato have an English proficiency level which does not satisfy the requirements to perform the different activities. They explained that during hiring processes, candidates who have graduated from the University de Guanajuato can demonstrate abilities that meet the requirements of the work positions, but they do not have the basic skills to communicate in English. This is suggested in Extract 6.

Extract 6. Employer 8’s Quote

Sometimes I have found good candidates, with experience in the field that I am looking for, but their English level is not good enough for the position.

As suggested in Extract 6, the employers maintained that candidates that have graduated from the University of Guanajuato have the academic backgrounds desired for the posts, but they have shown evidence of low English proficiency. For them, when these graduates are hired, this results in problems to maintain communication with clients or directors from other countries. This is suggested in the extracts (7-9) below.

Extract 7. Employer 5’s Quotes

They [UG graduates] maintain ineffective communication with employers from different countries.

There is sometimes misunderstanding with employers from other countries.

Extract 8. Employer 3’s Quote

Our clients face difficulties to send them [UG graduates] abroad because of the language.

Extract 9. Employer 9’s Quote

The growth of the company is limited when people do not speak English because we need to report to directors in other countries.

The employers explained that when graduates from the University of Guanajuato are hired, they are unable to communicate with other people in their companies due to their low level of English proficiency. In general, the employers’ suggestions reveal the need to train students to face different situations in English so that they will be prepared to start a job in the areas in which they studied. As we will see in the remainder of this paper, the participants that attended the other sessions were able to verbalise the same needs, pointing to a recurrent discourse which reveals the necessity to enhance teaching and learning practices in the different fields and departments across the University of Guanajuato.

University Authorities, English as a Foreign Language Teachers, and University Students

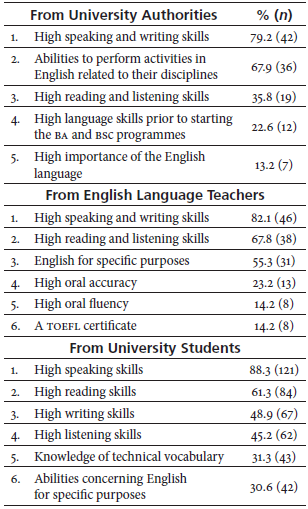

During the focus group sessions and in the questionnaires, the university authorities, language teachers, and university students were asked to generate their own ideas concerning their expectations regarding the English abilities of students at the University of Guanajuato. Table 2 summarises their responses.

In Table 2, it can generally be seen that the university authorities, English language teachers, and university students (a range between 35.8% to 88.3%) expect that teaching and learning provided by the University of Guanajuato develop the four English language skills. Moreover, 22.6% of the university authorities state that a certain level of English proficiency should be expected and measured during admissions with the intention of ensuring student candidates’ English abilities prior to commencing the BA and BSc programmes. Moreover, the students’ responses show that teaching and learning practices at the university are expected to develop the knowledge of technical vocabulary (31.3%) and English for specific purposes (30.6%).

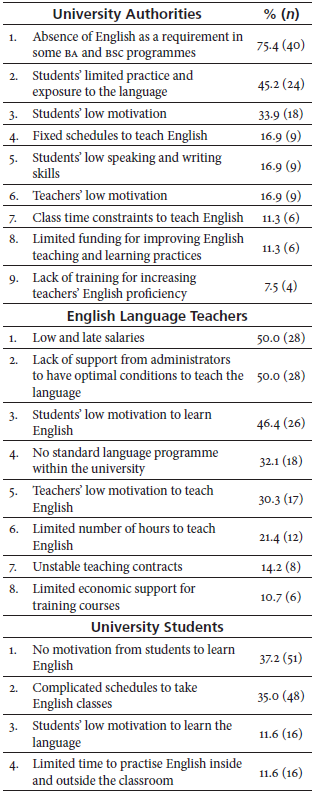

The participants were also asked about the challenges that they have perceived regarding English teaching and learning at the University of Guanajuato. Table 3 outlines these challenges.

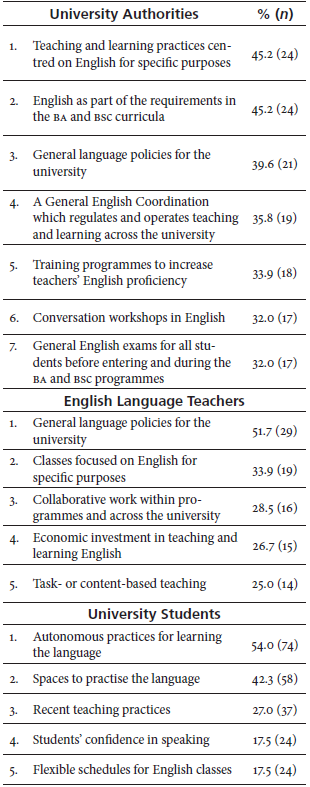

Table 3 shows that the participants perceived a wide range of challenges concerning English teaching and learning at the University of Guanajuato. In the three groups, it can be seen that they all perceived that students tend to have low motivation to learn English. In the case of the university authorities (75.4%), they felt that some BA programmes do not take into consideration the English proficiency of students in both the admissions and their teaching. Moreover, as expressed by 45.2% of the university authorities, students at the University of Guanajuato have limited exposure to the English language. It is interesting that 32.1% of the English teachers claimed that there are no standard language programmes within the university to teach English. As we will see, it seems that having English language programmes which are sensitive to the requirements of the different departments in the university is necessary in order to address the needs of these stakeholders concerning language proficiency. This suggestion is supported in some of the actions which were suggested by the university authorities, English teachers and university students who attended the workshops. Table 4 summarises their suggested actions.

As expected, Table 4 shows a wide range of actions suggested by the participants. As evident in the university authorities’ and English teachers’ responses, ESP seems to be an option which might enhance English teaching and learning practices in relation to employers’ needs (45.2% and 33.9%, respectively). More importantly, a considerable number of university authorities (39.6%) and English teachers (51.7%) believe that language policies for the university need to be implemented and formulated. These policies then need to be general for all the university but sensitive to the requirements of each department. It seems that an English coordination and language programmes which regulate and operate English language teaching and learning across the university might be beneficial for addressing the needs expressed by the participants and increasing the students’ English language proficiency to meet the demands of local companies in the State of Guanajuato. These ideas are integrated in a proposal for English language teaching and learning at the University of Guanajuato. This proposal is relevant to both the university community and local industries in the State of Guanajuato because challenges and plans of action have been suggested by the stakeholders in order to increase the English proficiency of future professionals from the University of Guanajuato and thus ensure that they join the local labour market.

The Proposal for an English Coordination and English Programmes

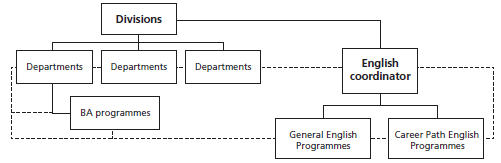

In order to address the second research question (how can these perceptual data be reformulated into a proposal which aims to enhance the English proficiency of students at this university?), I recommend that this HEI creates an English coordination which regulates and oversees the teaching and learning of English across the different departments, as illustrated in Figure 1.

The English coordination would also be responsible for updating the academic content of the English programmes across the divisions, giving teacher training in line with the programmes and pedagogic and administrative recommendations for meeting language objectives. It would also be responsible for designing and administering exams of different kinds. The function of the coordination to regulate English examination is of high importance because of the language standardisation which is necessary at the university. For this, it would be necessary to have an examination committee with English teachers and profession-related (discipline) teachers. This work is central to the success of both English programmes (see Figure 1) because it would create a cycle of collaboration among teachers which has a direct impact on the students’ English proficiency and thus the success of the programmes.

The English coordination, in collaboration with trained English teachers, would design and implement the “general English programmes” and the “career path English programmes.” As shown in Figure 1, I suggest that the English coordination not only continues implementing the general English programmes, but also designs and operates career path English programmes which are sensitive to the characteristics of each BA and BSc programme, and thus ensure that the English skills of students are developed as expected by the labour market. This suggestion is in line with the participants’ responses which revealed the needs to create language curricula which are sensitive to the nature of the different BA programmes in the university (see Tables 2 and 4). In this proposal, the career path English programmes would be designed as curricula which are sensitive to developing students’ English skills as expected by the labour market which they plan to enter. The impact of these programmes would be:

a short to medium-term effect on graduates’ employment resulting from new opportunities for them to develop English skills for occupational purposes; and

medium-term effects on social cohesion and economic development with more graduates in jobs establishing a collaborative relationship between businesses and the University of Guanajuato.

As suggested in the focus groups, it would be important that the general English programmes and the career path English programmes incorporate ideas and principles of content-based task teaching because its focus is to use language as a vehicle for authentic and real-world needs as in the labour market. In other words, it provides students with opportunities to experiment with spoken and written language through tasks which are designed to engage students in the authentic and functional use of language for meaningful purposes. Some of the benefits of this approach are the following:

active student involvement, empowerment, and autonomy

real life, authentic context of content

higher level of thinking skills

cooperative learning, collaboration, and problem solving

strategic reading and content vocabulary

In general, the general English programmes and the career path English programmes would aim at developing writing and speaking skills and vocabulary for work-related activities in national and transnational companies. However, I also highlight the importance of developing listening and reading skills so as to promote integral English language proficiency. In this proposal, I am thus suggesting that content-based English programmes (in the career path English programmes) be offered in connection with general English programmes (general English programmes). These programmes need to be:

realistic in terms of the language goals expected before, during, and after the BA studies;

context-sensitive regarding the nature of the BA programmes; and

integrative concerning the voices, perspectives, and experiences of the individuals who are immersed in the teaching, learning, and decision-making in the labour market.

I believe that by having these English programmes which have the objective of developing skills as expected by the labour market, the needs and actions suggested by the participants would then be addressed progressively.

Conclusions

The University of Guanajuato has designed and implemented several strategies to promote students’ development of English skills which allow them to enter the labour market. However, this institution has seen several limitations concerning the teaching and learning of English. In response to these perceived limitations, two NA cycles were conducted with four groups of stakeholders, that is, the heads of human resources in locally-based multinational companies, University of Guanajuato’s authorities and faculty members, language teachers, and students from different disciplines. This NA study involved a series of focus groups and questionnaires which took place between January 2018 and February 2019. The objectives of this NA study were to explore the stakeholders’ expectations, needs, challenges, and suggestions regarding English language teaching and learning at the University of Guanajuato; and to understand how this evidence can be reformulated into a proposal which enhances the English proficiency of students at this university.

The data collected in the focus groups and questionnaires yielded valuable insights into how the teaching and learning of English at the University of Guanajuato can be improved in order to increase the number of graduates who successfully enter the labour market. The voices and perceptions that were included in this proposal generally revealed that more agentive practices should be carried out to ensure that (a) English language goals are attained, and (b) the students of this university have better opportunities to enter the competitive labour market after their BA studies. In order to attain this, it was suggested that the University of Guanajuato creates an English coordination which regulates and oversees general English programmes and career path English programmes across the different departments. This would thus address the needs and suggested by the participants and promote the attainment of goals concerning English proficiency at this university.

To ensure its effectiveness, it would be important that more NA cycles are conducted to better understand how to implement the general proposal and set of recommendations with a view to obtaining positive attitudes and acceptance by the university community concerning this change. I believe, however, the present study attained the objectives of exploring the stakeholders’ needs regarding language achievement and understanding context-sensitive solutions which may be beneficial for enhancing English proficiency in this HEI. I hope that this study, its results and general proposal are useful for other HEIs which are currently facing challenges concerning students’ English proficiency.