Introduction

This paper aims at presenting a bottom-up perspective in the understanding of the role of teachers in the implementation of educational policies. We think it is important to hear from teachers themselves how they experience educational policies and how they face the multiple challenges and conflicting discourses that surround their implementation. Each time an educational policy is issued, the national government expects it to work regardless of its feasibility, the provisions (or not) made for the implementation, and the training teachers receive to set the policy in motion. The government is particularly strategic in selling to the general public the idea that certain policy is needed by using two mechanisms. On the one hand, it circulates discourses that on the surface seem to represent the needs of the community, when in fact they are very far from them (van Dijk, 1997), and on the other, the government hires external agencies (so called “experts”) to back up their educational polices showing that they value more the voice of “experts” than the voice of teachers.

Despite the call of many scholars and researchers to include teachers in the design of policies, in most parts of the world educational policies follow a top-down approach where policy makers design them and teachers are reduced to the role of implementers (Shohamy, 2009). Leaving out teachers, school contexts, and the needs and interests of communities results in monolithic and homogenizing policies. Colombia is no exception and teachers are constantly flooded by new policies; they are expected to achieve the goals set by the government which generally are not rooted in reality and are, therefore, unattainable and unrealistic. But, when policies do not work, the government does not take any responsibility and places the blame on teachers (Apple, 2002; Wink, 2000).

Our purpose, then, is to show that such a perception is not accurate because in fact what happens is that teachers do “whatever it takes” to make things work; they adapt policies in order to better serve the needs of their communities, and they search for different ways of compensating for their lack of preparation to teach English with the purpose of balancing governmental regulations and students’ needs.

This piece is part of a larger study framed within the socio-critical perspective that highlights a dialogic relationship between discourse and society (Bourdieu, 2003; Fairclough, 1992; Foucault, 1970/2005). Its purpose was to investigate the voices of some elementary school teachers about the design and implementation of educational policies, in Bogotá (the capital city of Colombia). The data were collected through five focus groups over the period of an academic year. The inductive analysis of the data led us to conclude that elementary school teachers are not passive implementers of policies but that they take actions, have their own perspectives about policies and their relationship with education, and are very aware of the treatment (or mistreatment) the national government gives them.

In conclusion, this paper attempts to leave the reader some food for thought to challenge the belief that teachers are passive followers; instead, we should see them as intellectuals (Giroux, 1988) who play a quiet yet effective role in both the implementation of educational policies and in filling the gaps left by policy makers and technocrats (Shohamy, 2009). The knowledge, expertise, and contributions of teachers should be regarded as a cultural capital even if, as in many cases, this form of capital is not institutionalized (Bourdieu, 1986; Foucault, 1972).

Background of the Study

The origins of this research can be located, on the one hand, in previous studies about the images of teachers in official discourses and in the media carried out in Colombia (Correa & González, 2017; Guerrero, 2010; Vargas et al., 2016) and on the other hand, on our own experience as teacher educators. In regard to images of teachers, Guerrero (2010)-using critical discourse analysis-shows that teachers are portrayed in a very negative light in one particular document issued by the Ministry of Education of Colombia with the occasion of the implementation of the so called “National Bilingualism Program” (PNB for its initials in Spanish).

The role of mass media has also been critical in shaping teachers’ negative images as found by Vargas et al. (2016) in a study in which they collected online opinion articles published from 2010 to 2014 along with the responses by users of the site. These opinion articles were published by the two major Colombian newspapers and dealt with three main educational policies. The main objective of the study was to analyze how readers constructed their own concept of educational policies; some of their findings show that journalists and readers alike think that teachers are unprepared, lazy, and do not care about students.

In another study that involved media and teachers, Correa and González (2017) conducted a research project in which they analyzed how major Colombian newspapers portrayed Colombian English language teachers. They collected news from 2005 to 2010 and found that not only were teachers presented in negative terms but also that these media had a strong influence on the negative perceptions Colombians have about teachers (particularly those working in public schools).

On the other hand, this study is also rooted in our own experience as teacher educators. Our professional careers have provided us with unique opportunities to interact with hundreds of school teachers around the country and to know firsthand their teaching stories. By listening to them in different scenarios (like conferences, workshops, and classes) we realized we should collect those stories in a systematic way to make teachers’ voices heard. For this study we invited elementary school teachers for two main reasons. First, because they have to teach English in elementary school although they do not have any type of training to do so; and second, because they are the least heard by technocrats in charge of designing educational policies. The national government always favors the “expert” over teachers. In our context, “experts” fall into three broad categories: (a) International agencies like the British Council which has been present in Colombia since 1945; (b) National agencies like the Fundación Empresarios por la Educación which do not have anything to do with education but are organizations whose main objective is to procure quality in the education system (as stated on their website); and (c) University professors, especially those who work in the private sector and are regarded as more knowledgeable (and who in some cases align themselves with the neoliberal take on policies). As Méndez-Rivera et al. (2020) put it: The world today relies on a techno-scientific knowledge in which only certain organizations claim the right to certify others. This relationship between “experts and non-experts” stimulates dependency and submission and leads to homogenization, which is the ultimate goal of “experts” since their economic interest lies there.

The situation is even more critical in developing countries like Colombia because, as a former colony, traces of colonialism and coloniality1 are still evident in governmental practices (González, 2007; Guerrero & Quintero, 2009) and which play very well with the neoliberal economic model adopted in the country in the late 1980s motivated, mostly, by the need (the same as other Latin-American countries) to renegotiate the external debt (Díaz-Borbón, 2009). In this context of colonialism, coloniality, and neoliberalism, teachers (in general) are not heard or consulted about the relevance and/or feasibility of educational polices, let alone elementary school teachers.

But while technocrats have the technical and theoretical knowledge, they lack the knowledge of reality that teachers possess. Colombia is mainly a rural country, affected by more than 50 years by an armed conflict, where teachers and students are the target of crossfire among paramilitary groups, guerrilla groups, and state agents. Studies like the one conducted by Lizarralde (2003) and Restrepo-Méndez (2019) show the distance between technocrats and teachers in regard to what is needed in terms of educational policies in a vastly complex context like the Colombian one.

Theoretical Framework

The relationship between educational policies, teachers, and neoliberalism is a rich, challenging, and provoking one. We have divided this section into two parts. In the first one we will discuss the pervasiveness of neoliberalism in education and in the profession; and in the second we will address conflicting discourses (which stem from neoliberalism) where teachers find themselves caught in the middle.

Teachers Under Suspicion: Neoliberalism in Education

The State plays a crucial yet contradictory role in school reforms in times of neoliberalism. On the one hand, loyal to the ideal that the State should provide and take care of its nationals, it is the State, through its government, that organizes and controls the school system; the government sets directions in terms of curricular content as well as in terms of financial resources like regulating teachers’ salaries and students’ fees (Apple, 2003). Some of these measures cover both public and private schools whereas others apply only to the schools funded by the State. Private schools determine their teachers’ salaries, hiring modalities, teachers’ duties, students’ fees, and so on.

On the other hand, the State owes itself to the neoliberal principles that, as in the case of Colombia, it decided to adopt in the late 1980s. In that sense, it seems the State no longer exists to protect its nationals but to serve the interest of the market. As such, the State keeps reducing the monies allocated to finance public schools and facilitates the creation of private schools, covered in discourses such as efficiency, efficacy, and productivity which, in the short run, “subordinates education to commercial values and vocational skills” (Levidow, 2005, p. 156).

Neoliberal reforms in education have brought policies that have harmed the educational system at the level of content as well as at the level of schools’ autonomy and employment stability. By adopting neoliberal discourses and practices in education, the public-school system has been debilitated and, as stated by Apple (2003),

This involves conscious policies to institute neoliberal “reforms” in education (such as attempts at marketization through voucher and privatization plans), neoconservative “reforms” (such as national or statewide curriculum and national or statewide testing, a “return” to a “common culture,” and the Englishonly [sic] movement in the United States), and policies based on “new managerialism,” with its focus on the strict accountability and constant assessment that so deeply characterize the “evaluative state.” (p. 7)

Although the context of this text is mainly the United States, it is very relevant to say that the current situation in Colombia is no different; as stated by Díaz-Borbón (2009), Colombia has been under the patronage of the United States in what has to do with economic policies. Sadly, these school reforms have changed the very nature of education; while for pedagogues the aim of education is the holistic education of the human being, for neoliberals it is about fulfilling the demands of the market and being productive moneywise; while for pedagogues students are unique human beings with the potential to be whatever they want, for neoliberals students are products that can be adapted according to the needs of the clients; for pedagogues there is an epistemological relation between the teacher and the students while for neoliberals there is a transaction between seller and buyer (Díaz-Borbón, 2009).

Under the spell of neoliberalism, policies that search for the homogenization of education, the adoption of a national curriculum, the implementation of standardized tests, the marginalization of indigenous languages, and the promotion of English as a superior language are all measures established to enhance productivity and guarantee revenue (Bruno, 2007; Shohamy, 2009). Instead of moving forward to a more inclusive and diverse world, we are walking backwards to the 18th century to claim “one language one nation” as the way to economic and social progress. But more problematic is that by adopting these measures, we witness, as put by Apple (2003): “the reproduction of both dominant pedagogical and curricular forms and ideologies and the social privileges that accompany them” (p. 7). So, it is not only that education is being taken over by those with neoliberal ideas but also that it segregates those who can have access to privileges from those who cannot.

Therefore, teachers are trapped within these discourses, practices, and policies and are deskilled (Sayer, 2012) by the minute. In the neoliberal models, teachers are not there to think but to do, and students are there not to learn but to acquire the necessary skills to perform in the labor market. Teachers are viewed as technicians who have to follow directions, obey distant authorities (Giroux, 1988), and make things work, and of course they are under constant suspicion: That is why the government fosters the implementation of surveillance devices like tests, periodical teachers’ performance evaluations, lesson plans, working plans, and tons of other formats for teachers to “prove” they are really working (Escalante-Gonzalbo, 2019).

Teachers Between Dichotomies

Shohamy (2009) calls for the need to include teachers in the design of educational policies. As many of us think, she claims that teachers could greatly contribute to designing polices that are more connected to school realities; their expertise and knowledge can help set attainable goals since, as Shohamy states:

A big disconnect exists between powerful policy statements and those which are practice-driven; this can help explain the reasons why policies often fail as they are driven by wishes and aspirations, which may be good in themselves but not always feasible. (pp. 46-47)

Unfortunately, with the adoption of neoliberal models in education, this is far from happening; meanwhile, teachers are still caught up in dichotomies and tensions that have to do basically with their having to take sides, either with the mandates of the government or with their students and their needs.

Heterogeneity vs. Homogeneity

When talking about education, official discourses foster, on the surface, the idea that schools should be heterogeneous and favor diversity of all sorts: language, gender, class, race; teaching methods, class contents, school materials, and so forth; but practices go in an opposite direction (da Silva-Pardo, 2019). Aligned with neoliberal discourses of competitiveness, the government implements different mechanisms geared towards homogeneity; according to Shohamy (2009), the test is the most powerful one. She claims that the use of tests unfolds a series of actions that make people, whether they like it or not, end up accepting, embracing, and demanding homogeneity. Teachers are caught up in the middle of these conflicting discourses, juggling with the ambiguous demands of the government.

The School as a Site for Reproduction vs. the School as a Site for Change

The school, as a concept, has been studied, analyzed, and problematized. For some scholars (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1970/1990; Freire, 1968/1996; Gramsci, 1995; McLaren, 2015) it is a site where the superstructures of society are reproduced. They see the way school life is organized, from the special layout to the contents studied and the ways they are delivered, as the perfect architecture for reproduction where little or no room exists to think critically. The school exists to discipline the body and the mind (Foucault, 1975/2012) in order to produce a submissive individual who obeys the rules of society and incorporates its practices without questioning them. But to others (Fraser, 1997; Hogan, 1982; & Wong, 2002 as cited in Apple, 2003) schools are places where social change can take place. For these authors, schools have been critical in challenging dominant powers and in bringing about social change. For them, there is a relationship between the school, as a government institution, and the school community where the latter have a rather active role in contesting the hegemonic practices of the former.

Teachers are then caught up in this dichotomy; on the one hand, they are part of the school as an institution, but on the other, as teachers, their role is to educate their students as holistic human beings. As we found in a previous research study (Guerrero & Quintero, 2016), teachers are caught in between deciding whether to comply with government regulations and mandates or to serve students’ needs. For many schoolteachers, students come first. This does not mean that they leave policies aside, but that they find a way to make policies work. These actions, or micro-practices, as we call them, should be visible and known by the rest of the society in order to understand the value and the contributions that teachers make for the same society.

Method

Our study is framed within a poststructuralist paradigm because we do believe that teachers’ voices do not simply reflect reality, but construct it while speaking (Agger, 1991); along with their voices, we will try to problematize and destabilize the given. We agree with Baxter (2008) and Hatch (2002) that there is not only one single story, let alone one single truth (Merriam, 2009), but many that deserve to be told. As stated above, this piece is part of a larger study conducted in Bogotá, Colombia. Using the social network strategy, we invited elementary school teachers from different localities of the district of Bogotá, and with the participating teachers we were able to form five focus groups in five localities.2 Each focus group was made up of eight to ten teachers whose ages ranged from their twenties to their fifties; there were female and male teachers.

According to Galeano-Marín (2010) focus groups fall into two main trends: the European and the American. The European differences itself from the American in that the former does not allow the moderator to intervene too much, while in the latter, the moderator controls the conversation. In our case, we adopted the European format because it was our interest to collect as much genuine information as possible. Also, focus groups lend themselves as a suitable methodology because we wanted to gather teachers’ opinions, ideas, and perspectives on one particular issue: the implementation of educational policies. We met with the teachers at their own schools (all of them public schools) over a year. Data consisted of recorded audios and videos and teachers were asked to sign a consent form.

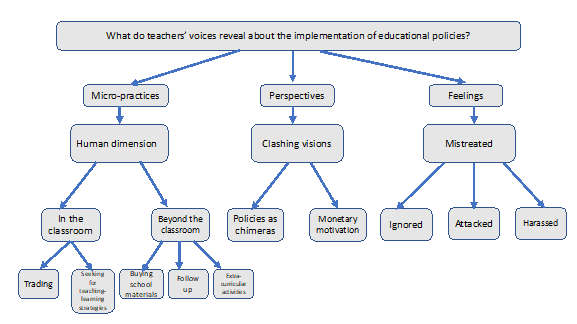

Grounded theory was the approach we used to analyze data because, being consistent with the poststructuralist approach, our interest was to dig deep into the data to theorize by finding emergent categories. The unit of analysis was chunks of data where teachers made declarative statements expressing actions, opinions, perceptions, or ideas. The analysis was guided by the research question: “What do teachers’ voices reveal about the implementation of educational policies?” and was done manually using both open and axial coding. We also used two forms of triangulation: peers’ triangulation, in which we invited other researchers to cross-examine the data and our interpretations, and theory triangulation, in which we confronted the emergent categories with existing literature.

Findings and Discussion

After immersing ourselves in the voices of elementary school teachers, and as an answer to our research question, we found that teachers take actions-which we have called micro-practices-have their own perspectives about policies, and feel negatively treated by the national government. In Figure 1 we illustrate these categories and their subcategories.

Teachers’ Micro-Practices

This category allows us to see that despite the pervasiveness of neoliberalism in education (Apple, 2003; Bruno, 2007; Díaz-Borbón, 2009; Levidow, 2005; Shohamy, 2009) teachers still put their students and their needs first when implementing educational policies. Teachers are very engaged with the profession and with the responsibilities it carries, which, many times go beyond the instructional or disciplinary aspects of teaching. We observed that teachers carry out lots of different actions either within their classrooms or beyond, that were neither part of the curriculum nor in their capacity as teachers; and that they did not share with other colleagues or administrative staff. We called this pattern micro-practices and define them as actions that teachers do on their own, quietly, either within the walls of their classrooms or beyond those walls.

These actions are their own because they are not initiated by the principal of the school, by any external agent, research group, consultant agencies, or official projects or initiatives. The other characteristic is that these actions take place quietly; by this we mean that teachers do not brag about what they are doing, and they do not invite anyone to be part of this action. By talking to them we figured out that they do not share their actions because they think they are meant to do these things as teachers, it is their job, and they do not see anything extraordinary about what they do. The third characteristic of micro-practices has to do with the scenario where these actions take place. Sometimes teachers engage in actions that reach beyond the classroom, but most of them happen within their classrooms while they are teaching. The classroom is the place, as we reported somewhere else (Quintero & Guerrero, 2013), where teachers feel powerful (in professional terms); they know their children and their contexts, and invent multiple ways to serve their students’ needs and expectations; to fill in the gaps left by policy makers and to fulfill the immediate needs of their contexts is a priority. As one of our participating teachers puts it:

If you are a teacher, you always want to do more for your students and then, as much as possible, because if you see that something…is missing…fortunately in primary school we have that…like that advantage, that as we are almost all the time with the group, yes? So, uh…we can within closed doors, when one is in the classroom eh…do something that you see that the kids are needing and that…that arises from your experience, of observing, of what to do, right? that is happening naturally, that is the contribution that one can make. (AC-N)3

The Human Dimension of Teaching

When looking at the way many educational policies have been drafted, one can see they seem detached from reality, cold and distant. As stated by Shohamy (2009), policy makers’ decisions are influenced by ideology, politics, economy, but “lack a sense of reality” (p. 46). It seems that policy makers forget that the act of teaching-learning is an act of humanity, or an act of love, as Freire (1992/2004) would say. Teachers, instead, are very clear about the nature of their profession. Students are human beings who, beyond grades, tests scores, and rote learning, have their own lives, which, of course, they bring into the classroom.

We learned that the human dimension of teaching is the driving force behind the micro-practices, that is, teachers’ actions are informed, driven, and inspired by it. Teaching is not a result-oriented practice that focuses only on doing as superiors say. In the participants’ declarations there are recurrent references to the place of caring in their teaching and the decisions they make in order to better serve the needs of their students. The excerpt below illustrates this point:

What does one do in the classroom: The children arrive, one greets them, one looks at them, one asks them if they had lunch, who brought them, who brings them, with whom they sleep, why they did not do the homework, why the mother and father are not living with them. One also helps them academically when they do not understand a task; after a weekend they come home without the homework, what happened? Why did he not make the homework? Nobody helped them at home so one takes him, separates him from the group and dedicates some time to the children that have problems. (PN_Solecito)

In the data we identified that teachers’ micro-practices fall into two main kinds: one that has to do with teaching per se, and happens in the classroom, and one that spans beyond the classroom and implies other forms of caring.

Micro-Practices in the Classroom. As we stated above, the classroom is where teachers feel powerful (Quintero & Guerrero, 2013), they feel their knowledge matters, and they feel they are really in charge and can make their own decisions. Being aware that they lack the preparation to teach English (teachers in elementary school do not receive any training in this matter), they find ways to compensate for this by taking informed actions. They “trade classes”; this means that if, by any chance there is a teacher who is good at teaching English, they switch groups, as we can see in this excerpt:

I have always looked for her, to deal with English in my group, so I had to go to her classroom to teach her kids religion, physical education, ethics, drawing, whatever I had to do, and she would come to mine to teach English to them. At least, the children take away a little foundation, a base for their high school. (AN-P6)

Another micro-practice is using others’ knowledge to learn some tips and strategies. For example, when there are student-teachers in the school, teachers ask them to come to their classrooms so they can take notes on both their pedagogy and their language usage (particularly in pronunciation which is something that worries them a lot). Others, led by intuition, search for materials or activities that they think might help children learn English. They adapt those materials to the number of students in the classroom, to the English level of the kids, their age, the particularities of the context, and so on. Although teachers find ways to cope and compensate for the lack of previsions in the design of the policies, these micro-practices have their dose of anguish, as the teacher in the excerpt below shows.

Then one makes moderate efforts, I say…the fact of being a teacher is definitely love, that is, I cannot say that I am a teacher by vocation, because it is not true, but I assume it with great responsibility, I cannot say what it was what I dreamed of…no, it was life circumstances that confronted me…but I think that when one assumes something, one has to assume it with full responsibility and then in those terms I assume it, well, I said well, I will have to do something and more with young children, well, one says, let’s use playful activities, let’s use songs, let’s use whatever tools we might know…but it is difficult. (AC-Jo)

Micro-Practices Beyond the Classroom. The other kind of micro-practices we identified are those that span beyond the classroom, which are also informed and motivated by the human dimension of teaching. On the one hand, we found that many teachers buy classroom materials for those kids who cannot afford them, and without second thoughts, they do this from their own pocket money. We also found that, in some cases related to child abuse or children with cognitive disabilities, they made a personal decision to visit the State offices in charge of dealing with those cases, and/or visiting children at home. And a third set of micro-practices beyond the classrooms was that in which teachers used their free time to teach children non-academic activities like playing chess or playing music. The excerpt below illustrates these micro-practices.

There are no spaces, there are no times, but sometimes one has the will, for example I work here with a small group teaching them chess, here in this lounge I work a few days, I have a small group but I would love to have a large group. (PN-Biribis)

Summing up, micro-practices constitute an alternative (in parallel) to teaching practice, in which the latter is the bulk set of activities that teachers must do: grade, instruct, discipline, punish, fill out forms, hand in report cards, behavior cards, attend meetings, and so on and so forth. Micro-practices, on the other hand, are those tiny actions teachers carry out in or out their classrooms and that are not contemplated in the syllabus, or on any administrative check list.

Perspectives

Under this category we present the perspectives teachers have on educational policies and show how divergent these are in regard to those held by policy makers. In what follows we delve into those perspectives.

Clashing Visions About the Purpose of Education

Teachers’ voices reveal that their visions about education differ greatly from those who design them. As discussed in the theoretical framework, most of the Western world has adopted a neoliberal model that crosses all instances from economic to educational. For teachers, it is very clear that educational policies are dictated by supranational organizations like the IMF, the World Bank, and the OECD (Nussbaum, 2011); in that sense it is clear to them that these policies have nothing to do with our context and needs. The data led us to identify two prominent ideas about educational policies: (a) Policies as a Chimera; (b) Policies Have a Monetary Motivation.

Policies as a Chimera. There is a generalized idea among teachers that policies are acontextual, homogenizing, and do not respond to the needs either of the society or of the students. By examining the educational reforms adopted under the neoliberal model, as stated by Apple (2003), it is apparent that these are not intended to improve the quality of education but to set the grounds for capitalism to consolidate in our emerging economies. Therefore, the promises of better education become a chimera. As stated by Díaz-Borbón (2009), for teachers, education has to do with caring and helping human beings to achieve their epistemological potential; for neoliberalism it has to do with maximizing the use of financial and human resources while reducing policy implementation to filling formats and reporting figures (Han, 2017). The following excerpt presents this clashing vision:

I would like to say something about the coverage policy, I think it is important to keep in mind that the established parameters are inadequate, they are not the most appropriate; 35 or 40 students per classroom; overcrowding; mega-schools; there is a great deal of investment in infrastructure but they have not invested in the quality of the education of the teachers; not of the students because after all, if one is well prepared, if one does research (not only doing things by trial and error) it can provide…provide a better quality education, that should be, among other policies, should be quality-oriented, it should not be oriented towards how many children pass the school year, and what the dropout rates are, and how many are repeating the grade; so, not to focus on the numerical part, but more on the knowledge part. Right now, everything is numbers, how many passed the test, how many passed the ICFES, how many children passed and how many failed. So that is failing the truth. (AN-P4)

Monetary Motivation. Policy makers, probably with good intentions, prioritize labor the market and the demands from the OECD (Colombia became a member in 2018) and those of the free trade agreements signed by our country. As a consequence, policy makers bring neoliberal practices to schools (Apple 2003; Ayala-Zárate & Álvarez, 2005), which changes the humanistic nature of education for one that cares about the production of goods. As such, discourses that include lexical choices like indicators, quality assurance, efficiency and efficacy, client, budget and others have been naturalized by schools.

Teachers claim that the economic interest is at the core of policy making and that the State makes decisions depending on how much money a policy will cost and what the revenue will be. The excerpt below voices this concern:

Or we see in Decree 230…the background of everything is an economic background, why? because each child who repeats a year has an economic cost for the governments. The 230 was intended to cut expenses to the maximum; only 5% of children could repeat a year, uh…Article 9, I think is the one that talks about 5% repetition in the courses, so you can see clearly…that…money-saving process, what economists call fiscal adjustment. (JP-Misudo)

Here, teachers are talking about a decree that rules on the percentage of repetition per course. It cannot be over 5%. Teachers interpret this decree not as a strategy to improve the quality of education but as a way to save money. Unfortunately, in this neoliberal system, money that goes to schools is not seen as investment but as waste (Apple, 2003; Manzano & Salazar, 2009). This other excerpt reinforces this vision of the prevalence of the economic aspect over the educational one:

If you see the need for Colombians to be taken into account, for the population to be taken into account-because that is what matters least to them, for them matters that a teacher has 45 students in a classroom; they don’t care if they are well prepared, or not; they care that there are 45 students per a teacher; that the teacher produces, yes? And it is advantageous in the economic aspect, but they do not care if the child can learn, or the child cannot learn. And we see that right here in Bogotá, the children who are studying in this area are different from those of XXX, they are different. (AN-Lucecita)

All and all, teachers are very aware that policies are strongly attached to economic interests in two ways: (a) making schools sites for the reproduction of the status quo (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1970/1990; Freire, 1968/1996; Gramsci, 1995; McLaren, 2015) and as a key piece in the gear to supply a cheap workforce for the labor market; and (b) seeing schools as money drainers, in which case, the objective is to reduce their budget and force them to survive. This, of course, enhances the inequality in the country (Colombia is the fourth most inequitable country in the world, according to the World Bank Group, 2016), because if teachers do not have all the financial resources to offer a good education, their students will drop out school to thicken poverty belts.

Feelings

An unexpected category emerged in our analysis which had to do with the feelings teachers hold in regard to policies. We found that they felt, constantly, negatively treated by State agents; their voices led us to characterize this category as follows:

Teachers Feeling Mistreated by State Agencies

Teachers voices also reveal that they feel mistreated by the National Government and by policy makers. This is consistent with Guerrero’s (2010) findings which show that the Ministry of Education has constructed a very poor image of teachers. Indeed, teachers feel ignored, harassed, abused, and attacked (which are the most common words they use to express their feelings):

Many times, we feel attacked, that is the truth. Because they attack us; this is how we feel, they attack us, they practically attack us, because they subject us to doing things without our consent and without seeing what the characteristics of our children are; what our characteristics are, and what are the means we have to make those changes and those approaches that they bring. So really, the aggression is strong and we feel it that way, and many times you do not participate…that is why, or many times you do things wrong because you do not have a personal motivation to do it, because one realizes that one is not taken into account at all and neither are children. (AN-P2)

As stated by Giroux (1988) teachers are viewed as mere technicians, their role is reduced to implement policies with no questions asked. Teachers are then, as Sayer (2012) puts it, “deskilled”; ripped of their knowledge, expertise, and abilities. Their voices are ignored because they are not considered “intellectuals” but implementers. And teachers do feel this disdain from the State which, in turn, leads them to stop participating when the State calls for feedback on new policies; of the older ones, experience has taught that their ideas will never be taken into account. Here the voice of one of the teachers:

All the voices were not heard, so, this policy is not accompanied by the voices of the teachers, so at one point they said that if we all participated, this would be it, but now, at the time of implementation, they have never come to ask “how is it going teachers?” They have never evaluated the impact of this policy in the schools. About the Decree 1290, they have never asked what has happened in the schools, is it working? Is it not working? and it turns out that now they call the headmasters and the coordinators and they are told we have to get our act together because a lot of children are going to fail. (AC-AiD)

Teachers also claim they feel harassed, and as we stated in the theoretical framework, teachers are constantly under suspicion; they have to fill in endless forms to prove they are good teachers. Paradoxically, to prove they are good teachers they only need to fill in forms; teaching is reduced to a report. This means that teaching is not important; what matters is whatever is written in the form. And school directors flood teachers with these assignments which leave very little time for actual teaching. Here is what one of the teachers says about this:

And then, the directors end up harassing the teachers, telling them “I need these formats, I need this implemented, I need them to develop eighty thousand projects” and because all those policies respond more to a “boom,” completely like this. They absorb us and we end up saying: “Well, what am I going to do with all this?”, what we do then, is to try to comply. To comply, but processes are not really being executed; school administration only and exclusively care for the formats, we are required to fill in the formats, that is what they pay attention to, but not the real work we do with the kids; the most important, which is the child, is completely forgotten. (AC-Jo)

We can conclude here that opposite of what is constructed in the media about who teachers are (Correa & González, 2017) and the constant neglect of governments to include teachers in the design of policies, teachers are critical of the norms imposed top-down by the government. Also, that neoliberalism in education takes a toll, not only in the quality of education per se, but in the personal and professional lives of teachers who feel despair more and more about their role in the implementation of policies, but who also find the strength to keep fighting for their ideals.

Conclusions

The adoption of neoliberal models in education are here to stay. Day by day those discourses and practices become more and more naturalized which makes it harder to problematize and, eventually, eradicate them. Discourses about the internationalization of education, globalization, and standardization for the sake of freedom nurture the ideas that neoliberalism does serve the individual needs of subjects. What it fails to show is that education is not a factory; students are not products for the market, and teachers are not clerks (Giroux, 1988). Teaching and learning are human activities, which imply a dialogical relationship that cannot be reduced to forms and figures. As stated by Escalante-Gonzalbo (2019) it is true that education should prepare people for work but it is also true that there are other purposes which are important too, like teaching students to be good human beings, to act ethically, and to care about others, for example. Unfortunately, in the race for pleasing the markets, policy makers are leaving out these other purposes and stripping teaching of its true meaning, emptying it of its humanity.

But, as a consequence of this, teachers do not give up, and despite feeling mistreated and silenced, they keep working to compensate for those flaws; teachers find different ways to resist the deskilling practices brought on them by neoliberalism to fight for their ideals and to secure a better future for their students.