Introduction

The importance of not only knowing but also mastering English as a foreign language (EFL) is undeniable in our era of the “Global Village” where information in the scientific, technological, political, and economic fields at the spoken and written levels are mostly found in this language. Hence, we speak of a global language such as a “lingua franca” that allows different peoples, nations, and races of different languages to communicate through a common code (Cromer, 1992; Ku & Zussman, 2010; Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN], 2006a). This characteristic growth of the importance of English has also produced the phenomenon of the native speaker displacement as a standard. At the level of native English speakers in countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, it has been found that there would be almost five times more speakers of EFL than natives throughout the world (Jenkins, 2003).

In the educational field, the importance of English, especially in developing countries, has been growing due, for the most part, to frequent opportunities for educational mobility offered worldwide to students of higher education (British Council, 2015; Pennycook, 2012; Sánchez-Jabba, 2013). Therefore, the inevitable requirement of mastery or proficiency of EFL has been on the increase. This reality has recently been boosted by the so-called “internationalization” factor that has been taken into account by the universities in Colombia to improve the mobility rates for the accreditation of programs and eventually of the institution. The national and international visibility of the universities required by the Consejo Nacional de Acreditación1 (CNA) as one of the factors for accreditation (Agreement 03 of 2014) and the internationalization dimension by the MEN for the Modelo de Indicadores de Desempeño de la Educación Superior (MIDE, higher education performance indicator model) university rankings has very recently included the results of English from the Saber Pro tests2 at university level as one of its indicators, among others such as student and teacher mobility, and international co-authorship of articles (MEN, 2014; Resolution 18583 of 2017).

According to recent reports in Colombia, the level of English has been identified as low, when considering the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) adopted by the Colombian government since 2006 (MEN, 2006a). This drawback has had direct implications for public education policies aimed at counteracting low language proficiency results for university students at both national (ECAES,3 Saber Pro) and international level (English Proficiency Index, EPI) exams for young professionals. On the other hand, taking into account the results of standardized tests, student performance, especially in higher education, has not changed significantly (Consejo Privado de la Competitividad, 2007; Sánchez-Jabba, 2013).

In this study, the reports from ECAES, Saber Pro exams, and the databases from the repository of the Instituto Colombiano para la Evaluación de la Educación (ICFES) are used for the analysis of the results in two moments along ten years (2007-2017). After a brief historical contextualization of the policy and the exam, the results that determine the different levels of English are compared with reference to the goals established by the MEN for that period of time. Finally, the implications for the future development of the linguistic and communicative competencies of English in the Colombian education system are examined in the discussion and conclusions parts.

International Context

In the early 1990s, with the disintegration of the Soviet Bloc, the Iron Curtain, the Berlin Wall, the Cold War, and other political, economic, and cultural barriers between East and West, there was an increase in student mobility in European countries, after more than 50 years of strong restrictions on entry to the countries of the Eastern Bloc. The same happened with the countries of the American continent that saw greater possibilities of international mobility with Europe. Both government agencies, industrial and commercial companies as well as institutions of higher education launched their different policies of rapprochement and cooperation with European countries and vice versa. EFL thus gained greater momentum as a means of global communication for education (Council of Europe, 2001; Gilpin, 2011; Lasanowski, 2011; McBurnie, 1999).

This resulted in the resurgence of interest in learning and teaching the different languages involved, especially English, from fields such as science, economics, industry, technological development, and the growing impulse of global culture (Nault, 2006). Also, the qualification of people in various languages was particularly important, as was the implementation of evaluation and measurement mechanisms. In addition, it was necessary that actors interested in cooperation and interaction in the new context could show mastery of the target language, making certain forms of institutional certification of their competence in the different languages at stake necessary (Coleman, 2006). This resulted in the need for the standardization of assessment and measurement instruments of internationally validated exams or tests (Benavides, 2015; Council of Europe, 2001; Willems, 2002).

In this way, the option of a standard for the different global certification needs of EFL was born, as well as for the other languages at stake (French, Spanish, German, etc.). Since the 1960s, there have existed language certifications from institutions such as ETS (Educational Testing Service) in America and universities such as Cambridge and Oxford in Europe that used various tests to measure linguistic and communicative skills. Many test developers at that time realized the need for a standard that could serve as a reference for the various certifications of the mastery or proficiency of a foreign language in the new world context.

In the mid-1990s, the Council of Europe proposed a series of guidelines-to be recognized throughout Europe-for learning, teaching, and evaluating qualifications in foreign languages. (Schneider & Lenz, 2001). The resulting effort was the development of the standard called Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) that would eventually become a reference manual for aligning tests for the different language competencies: linguistic, communicative, sociolinguistic, and pragmatic (Willems, 2002).

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages

The CEFR was published as a revised version of a Council of Europe manual in 2001. It aimed at helping European countries in their search for standards, criteria, and points of reference to assess and evaluate different levels of language in order to guarantee and promote interaction among peoples, especially in the field of education. One of its main objectives was:

To encourage practitioners of all kinds in the language field, including language learners themselves, to reflect on such questions as: What do we actually do when we speak (or write) to each other? . . . how do we set our objectives and mark our progress along the path from total ignorance to effective mastery? . . . what can we do to help ourselves and other people to learn a language better? (Council of Europe, 2001, p. iii)

The main advantage of the CEFR from its conceptions has been, as the name implies, to serve as a common reference for language teachers, researchers, and policymakers in establishing their objectives and challenges, taking into account their needs, interests, and contexts (Council of Europe, 2001). However, in recent years and from the pressure of a global economy and the need for policymakers for language choices, most of the attention placed on the CEFR has been focused on the achievement of the different levels built around descriptors and rubrics. In other words, the emphasis has been put on the adequacy and application of tests and achievement exams in the areas of international relations and business and commerce (Neeley, 2012, 2013; Spolsky, 2009). Despite the more pragmatical orientations and applications from its original aim by the Council of Europe, it can be of particular interest to policy designers, agencies and government institutions, curriculum designers, teachers, and institutions to implement curricula around these new standards to eventually have programs developed around descriptors of the international level (Little, 2007; Westhoff, 2007).

The Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo (National Bilingualism Program)

Colombia has prepared the path towards commercial, scientific, and educational openness using the Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo (PNB) since 2004 as an ambitious driving mechanism for the country’s development. Several reforms designed for EFL in the Colombian educational system preceded this program. In its design and implementation, however, structural obstacles were found that prevented its realization. Among them was the large number of students per classroom that became a great pedagogical obstacle to learning objectives. Also, these reforms revealed the wide gaps between national initiatives issued by the Ministry of Education for the policy implementation of English and the development of communicative competence of Colombians. These policies have been carried out amid the lack of continuity in their implementation due to (a) misconceptions of the term “bilingualism” (Gómez-Sará, 2017); (b) not enough available resources, the necessary contextual conditions, and the scarce hourly intensity and content (Jimenez et al., 2017; Sánchez-Solarte & Obando-Guerrero, 2008); (c) the lack of a culture of evaluation (British Council, 2015); (d) disregard of language educators in policy decision making and in-service teacher training and preparation (Cárdenas, 2006); and (e) impoverished opportunities of degree qualification for primary school teachers by the Ministry of Education (Bastidas et al., 2015).

It is noteworthy that during the periods 1991-1996 and 2011-2015, and in the context of decentralization promulgated by the new Colombian Constitution of 1991, the MEN, supported by several private and official universities and with the logistics of the British Council, promoted teacher training in the different participating English programs. This led to a mobilization of English teachers from several universities to enforce internal curricular reforms that would ultimately leverage English learning processes based on new approaches, methodologies, and pedagogical paradigms (Aparicio et al., 1995). The mobilization mentioned above nurtured the development in 1999 of the Curricular Guidelines for Foreign Languages as pedagogical orientations for teachers who could appropriate conceptual elements and make university autonomy effective in guiding the pedagogical processes for curricular needs (MEN, 1999).

Only until 2006, and in the context of the “Educational Revolution,” did the MEN publish the Basic Standards of Competence in Foreign Languages: English, a product created by university teachers with experience in the field and with the support of the British Council. These standards implied the adoption, selection, and application of the descriptors and rubrics of the CEFR, which were accepted as criteria to identify the development of English language linguistic and communicative competencies in the country (MEN, 2006a).

The PNB aimed at “achieving citizens capable of communicating in English, so that they can insert the country into the processes of universal communication, in the global economy and that of cultural openness, with internationally comparable standards” (MEN, 2006a, p. 6). The purpose, made explicit by the Ministry of Education, was intended to achieve levels of mastery or proficiency of English in Colombia for 2019. However, it could also have represented the adherence of the country to globalization as a mass phenomenon, synonymous with the “commercialization” of higher education, as seen by some critics of this process (Brandenburg & de Wit, 2011; Pennycook, 2012; Robertson, 2010). Conversely, Piekkari and Tietze (2011) have reminded us of the difficulty, if not the impossibility, to dictate general policies for language use and rather recommended a sensibilization process before setting any policy implementation. It seemed that this process was made to appear somewhat easy to achieve or it was intended to be perceived as too simplistic, without having considered the complexity of contextual aspects: needs, interests, motivations, the programs (form, duration, and orientation), coverage, participants, institutions, students, and teachers at the regional and national levels. Therefore, the introduction of language policy should have been for the most part an integration of the many factors, actors, and conditions of the process in the country as a precondition to its successful implementation, without neglecting any of the complexities while considering most issues at stake.

Analysis of the Goals Projected for the Development of the Level of English in Colombia

Through the PNB as a policy for the development of EFL in Colombia until 2019, the MEN aimed to develop communication skills in English for educators and students to favor the insertion of human capital in the knowledge economy and in the globalized labor market. For this reason, it considered the achievement of the goals as mastery of English (MEN, 2005, 2006a, 2006b). All accomplishments and achievements would have to be referenced to the standard adopted by MEN since 2006, that is, the CEFR and the consequent use of the new terminology: CEFR levels, performance descriptors, rubrics, scales, ranges and sub-ranges for the different language and communication skills that had to be guaranteed.

A scale of three ranks, for the six levels of the CEFR (A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2) was a more simplified manner addressing the levels: basic user (A1, A2), independent user (B1, B2), and efficient user (C1, C2). However, the latter two levels, according to the CEFR descriptors, refer more to the optimal levels of achievement of an ideal user who would resemble that of a native speaker of the target language. The basic user and independent user ranks were further divided as: Beginner A1, Elementary A2, Intermediate B1, High Intermediate B+. These were the levels obtained after the piloting of the test between 2005 and 2006 and the first results appeared in 2007 (see Table 1).

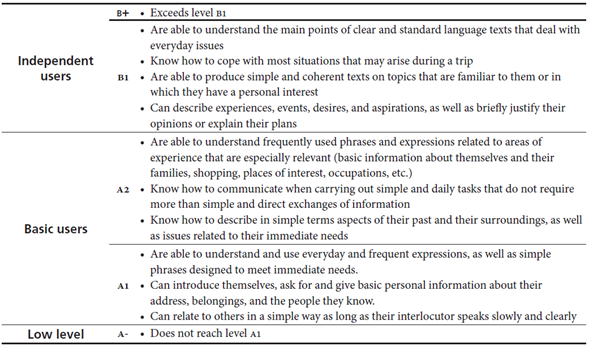

Table 1 CEFR Descriptors for English: Basic and Independent Users

Note. From the ICFES (2010), Saber Pro database. Dirección de evaluación.

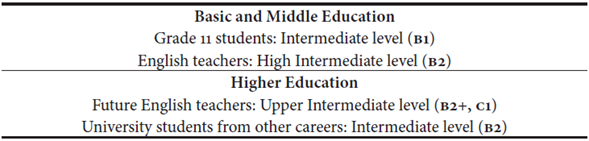

With the PNB as a base policy, the MEN considered that the specific goals for students who completed basic and middle education would be the achievement of levels A2 and B1, respectively, and B2 for teachers. For students who finished higher education levels, B2 and also B2+ would be expected, and C1 for graduates from English bachelor’s degree programs at university level (see Table 2).

Table 2 Achievement Goals for English: Basic, Middle, and Higher Education

Note. From Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo: Colombia 2004-2019, by Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2009, (https://bit.ly/3h1Bnif).

However, since the results at baseline (2005-2006) were lower than expected, projected goals were established in percentage figures for middle and higher education levels (see Table 3).

Table 3 Percentage Indicators, Baseline, and Goals (2011-2014)

| Indicators | Baseline | 2011 Goal | 2014 Goal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | % of 11th grade students proficient in English at the pre-intermediate B1 level | 11% | 15% | 40% |

| 2. | % of English teachers with an intermediate B2 English proficiency | 15% | 19% | 100% |

| 3. | % of English BA degree students who reach the intermediate level B2 | 31% | 45% | 80% |

| 4. | % of university students from other careers other than BA degrees in English that reach the intermediate level B2 | 4% | 6% | 20% |

Note. From Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2010-2014: prosperidad para todos, by Departamento Nacional de Planeación, 2011 (https://bit.ly/2ZsO0Nu).

Given the baseline, an increase of four percentage points as a goal for 2011 (see Case 1) could be understood as moderate. However, an increase of more than 100% in the following three years (2014) appeared very ambitious. In Case 2, the goal pointed to more than 500%, an increase in the same three-year period for teachers of English in basic and secondary education, something very difficult or impossible to achieve without having some kind of special intervention plan.

In the context of a globalized world, pressure for a foreign language policy has been exerted internally and externally. First, by governmental agencies such as MEN and the ICFES and the Consejo Privado de la Competitividad that would allow Colombia to be a competitive country with its insertion into the global economy and with better preparation for the academic and labor global world. Second, by international organizations like the OECD as a demand for the country to be in a better position in the education field by performance indicators on standardized tests. One of these indicators has been English as a primary means of communication in all fields ensuring the educational policies from international organizations dealing with market participation and adherence to a global and neoliberal context of higher education (Apple, 1999; Olssen & Peters, 2005; Phillipson, 2008; Price, 2014). Within this state of affairs of providing the expected results satisfying both sides, the MEN would have adopted two positions. First, a minimalist position for basic, middle, and higher education cycles, in the first three years of the English test for 2011, and second, a maximalist approach for the next three (2014) in the development of foreign language competencies according to the projected goals.

Results of Saber 11 Exam

The results of the level of English for primary and secondary education in this study are taken only as a reference for comparison and the subsequent analysis of higher education. For consistency purposes, the following nomenclature is used as terms of the scale: low levels (A- and A1), intermediate levels (A2 and B1), and high level (B+) or higher.

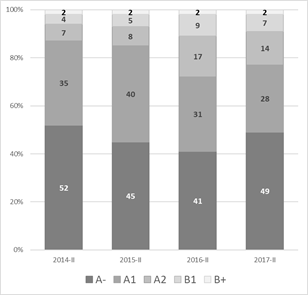

The following results of the Saber 11 exams carried out between 2014 and 2017 could be used to compare the scope of the goals projected by the MEN around the levels established according to the CEFR criteria and the real situation of English in basic and secondary education in Colombia (see Figure 1).

In these four years (2014-2017), the level of English in basic and secondary education appears practically as A1, A2, and B1 of the CEFR with their respective achievement descriptors (see Table 3).

In 2014 (year of the first goal of the MEN), 87% of the students of 11th grade who took the test were in the low levels (A- and A1), and only 4% reached B1 which, according to the MEN, for that year should have been 40%. Three years later, the results are nothing better since the goal for 2017 should have been much higher. However, 7% was obtained, 3% higher than (2014), that is a 1% increase per year. In these four years (2014-2017), there is no significant change to talk about language “mastery” as was proposed in the goals for 2014, with 40% for B1 finishing secondary education (MEN, 2006a, 2006b).

It is worrying to see that practically half of the population of students finishing Grade 11 in 2017 is at Level A- according to the CEFR, that is, the student “does not overcome the questions of less complexity” (see Table 1). If these were the results obtained at the end of the secondary education for 2017, these would be the levels of entry of students to higher education. Seventy-seven percent of the population with low levels (A- and A1) are even lower than what should be achieved, according to the MEN, at the end of primary school. Without obtaining Level B1 for secondary education, the projected goals for higher education would suffer in that same proportion affecting the overall level of English in the Colombian education system.

Results From the ECAES Exam for English (2007-2008)

With the issuance of Law 1324 of 2009, the regulatory framework of the System of Quality Assessment of Higher Education was introduced and new criteria for the English exam were defined. Decree 3963 of 2009 regulated the application of the exam, and Decree 4216 of that same year made its completion an additional degree requirement for students at the end of this level of studies. Since 2010, with the review of the exam, it was called the Saber Pro exam, and its results served as a source of information for the construction of indicators for evaluating the quality of higher education in Colombia.

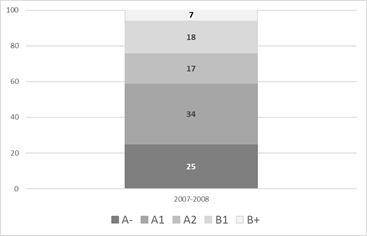

The following results (2007-2008) are the benchmark for subsequent comparison with the period 2016-2017 and they refer to professional programs at the university level in higher education. It can be noted that about 60% of the population that took the English exam in that first period is at low levels (A- and A1), 35% in the intermediate levels (A2 and B1), and only 7% in the high level (B+; see Figure 2).

Note. From ICFES (2010, 2011), results (2007-2008).

Figure 2 Percentage Results of ECAES National Exam, University Programs (2007-2008)

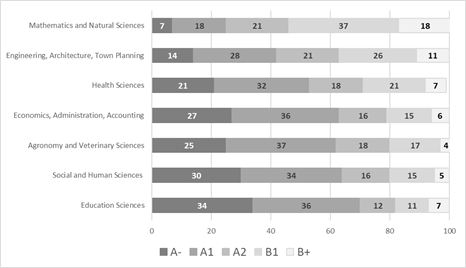

For the same period (2007-2008) the differences among the reference groups are notable between the extremes of the distribution. Mathematics and natural sciences with 25% of low levels (A- and A1), 58% in intermediate levels (A2 and B1), and 18% in the high level (B+). They are followed, in descending order, by engineering, architecture, urban planning, and health sciences. At the lower end are education sciences and social and human sciences. The education sciences group has 70% of the students in the low levels (A- and A1), 23% in the intermediate levels (A2 and B1), and only 7% in the high level (B+; see Figure 3).

Note. From ICFES (2010), results (2007-2008).

Figure 3 Percentage Results of ECAES National Exam, Groups of Reference (2007-2008)

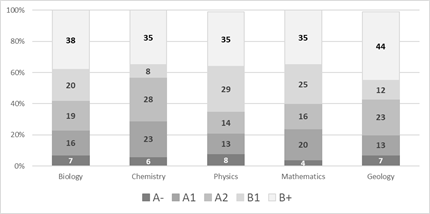

For a better comparison within the reference groups, some of the programs within them at the extremes of the distribution have been taken for comparison: mathematics and natural sciences contrasted with those of education sciences (see Figure 4).

Note. From ICFES (2010), results (2007-2008).

Figure 4 Percentage Results of ECAES National Exam: Mathematics and Natural Sciences (2007-2008)

These programs stand out due to the low percentages at the low levels (A- and A1) and high percentages at the high level (B+). It is important to note that the low levels are between 20% and 29%, while the high between 35% and 44%, which significantly differentiates them from the results of the population.

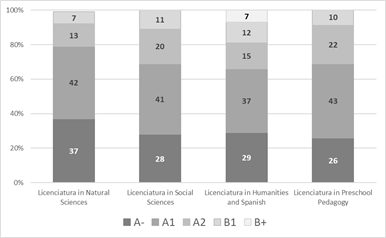

For the second case, in the bachelor’s degree programs from the education sciences group, high percentages in the low levels (A- and A1) reaching about 80% in one of them are observed, and the absence of the high level (B+) in the others (see Figure 5).

Note. From ICFES (2010), results (2007-2008).

Figure 5 Percentage Results of ECAES National Exam: Education Sciences (2007-2008)

Unlike the programs in the area of mathematics and natural sciences (Figure 5), these would be those with the lowest performance of the population: the highest percentages at the lowest levels (A- and A1) and the lowest at the high level (B+).

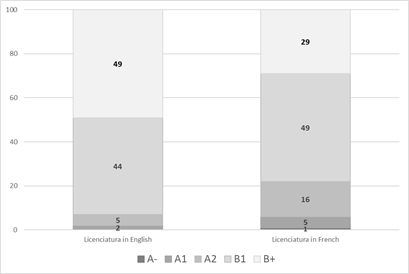

However, within the education sciences, the differences considerably increase when it comes to programs whose emphasis is foreign languages and particularly bachelor’s degrees in English (Figure 6).

Note. From ICFES (2010), results (2007-2008).

Figure 6 Percentage Results of ECAES National Exam: Bachelor’s Degree in Foreign Languages (2007-2008)

Even 2% of low levels (A- and A1), 49% intermediate levels (A2 and B1), and 49% at high level (B+) in programs with an emphasis in English, would not be sufficient for the goals established by the MEN in 2006. These programs, given their subject matter characteristics, would be the exception to the rule of what happens with the other university programs of higher education. Therefore, it would have been necessary to consider them separately.

Results of Saber Pro for English (2016-2017)

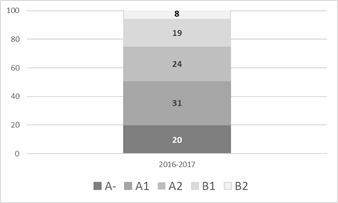

After ten years of the first application of the English exam, and with the modification of Level B+ as B2 after a revision of the test, roughly half of the population (51%) of those who took the test are still at low levels (A- and A1), 43% in the intermediate levels (A2 and B1), and only 8% in the high level (B2; see Figure 7).

Note. From ICFES (2018c), database results (2016-2017).

Figure 7 Percentage Results of Saber Pro National Exam (2016-2017)

The results are similar to those obtained in 2007-2008, ten years previously. There is a decrease of eight percentage points (5% for A- and 3% for A1) in the low levels, that is, less than 1% annual improvement for 2016-2017. There is an increase of eight percentage points in the intermediate level (A2 and B1), less than 1% annual improvement, and practically no difference in the high level (B2) concerning the results of 2007-2008. These do not represent any significant improvement in English for higher education over a period of 10 years, considering the magnitude of the goals established by the MEN in 2006.

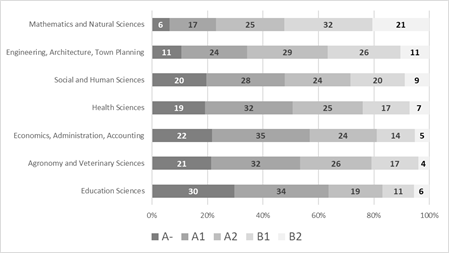

Concerning the reference groups, it is worth noting a marked difference in the extremes, like in the period 2007-2008. Mathematics and natural sciences with 23% at low levels (A- and A1) are far better than education sciences at those same low levels: 64% in a one-to-three ratio. In the high level (B2), 21% for the first case and 6% for the second, in a three-to-one ratio. However, there is a small improvement due to the reduction of the low levels of the two extreme groups, but more for the second, 0.2% and 0.6% annual improvement, respectively. The rest remains relatively the same (see Figure 8).

Note. From ICFES (2018c), database results (2016-2017).

Figure 8 Percentage Results of Saber Pro National Exam: Groups of Reference (2017)

When these results are compared with those of 2007-2008, there is consistency at both ends of the two groups. The only difference is from social and human sciences that now rank third in the reference group scale in 2017. The rest remains relatively invariable. It can be determined that in ten years, no major changes are observed. Therefore, a relative stagnation is evident in the development of the level of English as a generic core from the results of the ECAES, Saber Pro exams for higher education.

Discussion

The results of the English module of the ECAES, Saber Pro exams show that in Colombia, there is a significant percentage of university-level students who are still below the A1 level of the CEFR (25% in 2007 and 20% in 2017) at the end of their careers. In ten years, Level A- only shows a reduction of five percentage points, which represents an average of 0.5% annual improvement. The next level (A1) has a reduction as an improvement trend of three percentage points, for a 0.3% annual improvement. The best gain is at Level A2 with an increase of seven percentage points, for a 0.7% annual improvement. The intermediate and high levels (B1 and B+), which are the focus of the goals for English projected by the MEN, remain virtually unchanged with a slight gain of one percentage point in ten years, from 18% to 19% and from 7% to 8% from 2007 to 2017, respectively, that is, a 0.1% annual improvement in each case.

The improvement trend seems to move towards Level A2, which shows the best gain. However, the overall improvement is too small to be considered important for the “mastery” of the foreign language. Therefore, it could be said that the results show a process of stagnation of the development of English competencies in ten years. For example, the improvement of Levels B1 and B+ is a clear indicator of stagnation, because they are the focus levels by the MEN in setting the goals. If these goals were applied to 2017 as a requirement for graduation (as seems to be the case in the near future with Resolution 18583 of 2017), only about 8% of higher education students at the university level will be able to graduate.

Taking the goals established by the MEN as a point of reference, and the results obtained, it can be determined that the level of English in higher education is still very low, confirming previous analyses (Consejo Privado de la Competitividad, 2007; Sánchez-Jabba, 2013). In other words, it is not only the level of students who finish their university level that is very low but also there is not enough improvement during a ten-year period (2007-2017), as this study shows. In addition, the above findings are confirmed by the level of English of young professionals in the results of international exams where Colombia appears 68th among 100 countries in the 2019 world rankings. As for Latin American countries, Colombia is hardly above Ecuador and Bolivia, according to the 2019 results of the EPI (Education First, 2019).

The differences in terms of the results obtained in the period of this study for English communicative competence and the goals set by the MEN are so broad that a considerable gap has been created between them, and it is safe to say that the State is in debt with the language education system for the stagnation of the process of foreign language development. Consequently, this area would probably take a considerable amount of time, effort, and investment in order to catch up.

This gap started with the results of the Saber 11 exam, as seen in 2014, with more than 50% of the population at Level A-. Then the same debt must have been transferred to higher education in the professional careers at university level in those ten years and could be still happening. University programs would have been carrying that burden without any possibilities of medium and long-term solutions given the low level and minimum progress seen in a ten-year period for the development of English language competencies in the Colombian educational system.

It is also important to highlight the results of the reference groups that relate to a greater or lesser degree with the areas of knowledge. The large differences shown are consistent in the upper and lower end groups, with no major change in ten years, apart from a small decrease in the lower levels, 0.2% and 0.6% per year in the two extreme groups, respectively. However, it is important to consider the most likely reason for these differences in favor of mathematics, natural sciences, and engineering in contrast to education sciences. These differences are most probably due to the fact that in the programs of the first group, the students have to be reading bibliographic sources directly in English, which mostly cover up-to-date information on science, research, and technology. This would imply the use of bibliography and subscriptions to specialized journals in English and access to databases of specialized journals in science and technology over the Internet. The fact that students have to read directly from these sources in English would be guaranteeing them the learning through language use and consequently obtaining significantly better levels of English than those of the other programs.

Finally, it is contradictory that Resolution 18583 of 2017 demands that by 2019: “Higher education institutions must guarantee that graduates of all bachelor’s degree programs in teaching have a B1 or higher level in a foreign language, according to the CEFR.” Equally unlikely, would be to obtain a B2 level as a requirement for students of the other professional careers in the country in the long term. Even the goals required for programs with an emphasis on English expected to be at level C1 for 2020, according to the above-mentioned resolution, would be currently very difficult, if not impossible to obtain if the results of this study are taken into consideration.

Conclusions

The very low level of English communicative competence shown in the period 2007-2017 from the ECAES, and Saber Pro exams for university professional programs concerning the English module reveals a relative stagnation of the development of the linguistic and communicative competencies showing the real difficult situation of English in the Colombian educational system. Despite the overestimated goals of the MEN that insisted on a “mastery” of English in Colombia for 2019, the evidence shown by the results in this study is more than alarming. With the overall importance attributed to the knowledge and mastery of English as a lingua franca for the purpose of internationalization, student and teacher mobility, research and openness to other cultures, there would be no major change and development in the future without the redesigning of an effective foreign language educational policy and innovations and suggestions for teachers’ professional development at local and national levels as those proposed from research and implementation by Alvarez et al. (2015), Cadavid et al. (2015), and Cárdenas et al. (2015).

The absence of an effective state educational policy that fosters the development and use of the foreign language in all its competencies seems to have severely affected higher education and particularly the university programs. If there ever was a foreign language policy or the same with different denominations, these have not worked properly due to several reasons, but mainly for lack of continuity. The PNB, the Programa para el Fortalecimiento y el Desarrollo de Competencias en Lengua Extranjera, the Programa Nacional de Inglés, and Colombia Bilingüe, however, according to the results in this study, seem to have stayed on paper, or in theory, or only in their initial stages in the heat of the enthusiasm of the participants for the expected goals.

Moreover, it should be taken into account that the results of the Saber Pro exam are increasingly being considered by the CNA in order to grant Colombian universities program and institutional accreditation. One of the purposes of this exam is to serve as a source of information for the construction of indicators for evaluating the quality of higher education programs and institutions. By evaluating the level of EFL in the internationalization factor, the CNA assigns a weight of 2% from the new MEN-MIDE 2.0 ranking of Colombian universities.

Therefore, It would be necessary to undertake a drastic revision of foreign language policy as a joint research effort by the different English language departments, language schools, or language centers in charge of the administrative and academic organization of English courses and curricula to delve into the analysis of the foreign language policies of each higher education institution. The end result of this effort would be a more consensual view of foreign language policy and thereby a shared view of language education in general. This joint effort by universities would promote the effective development of English and its linguistic, communicative, and pragmatic competencies starting at primary and secondary education as an initial working platform. Foreign language educational policy should be revised and implemented, and a series of structural alternatives that would allow a sustained development in terms of teacher training, methodology, curricular organization, and use of the language in the programs should strongly be considered.

Finally, a macro research project by the universities in the country is needed. One starting in every institution that encourages awareness of the need for analysis of the situational context using the information available from the ICFES databases. This effort would launch a joint improvement proposal for a medium and long-term intervention strategy as an active and permanent mechanism for a foreign language education policy of development and the use of English in higher education. This course of action should eventually involve and impact the basic and secondary education cycles through the Municipal and Departmental Secretariats of Education.