Introduction

Reflection in English as a foreign language (EFL) in classrooms around the world has taken a relevant role among students and teachers, since it enables the analysis of actions taken during the teaching and learning processes (Manouchehri, 2002; Schön, 1983; Sockman & Sharma, 2008). Reflection entails a deep critical analysis and the questioning of all that surrounds us by taking a closer look into our reality (Schmitt, 1973); then, learners have the opportunity to start identifying their own strengths and weaknesses before any situation they face in life, in this case learning a foreign language. Therefore, EFL learners who continuously reflect upon their performance seem to achieve better academic results.

Likewise, self-assessment enhances students’ reflection on their weak and strong points (Rodríguez Ochoa, 2007); it affects learners’ performance since it fosters the decision-making ability to face problems and suggests ways to solve them (Caicedo Pereira et al., 2018). Moreover, formative feedback activates students’ reflection regarding their learning goals (Alvarez et al., 2014); when used properly, it directly relates to the parameters of assessment and to its timely, customized, and encouraging approach (Hatziapostolou & Paraskakis, 2010).

Accordingly, we examine the reflective process carried out by a group of EFL preservice teachers regarding their academic writing and the effect that self-assessment and formative indirect feedback has on the construction of their texts. Consequently, our research question is: What is the impact of reflective learning on a group of preservice teachers’ academic writing skills through formative feedback and self-assessment processes?

Statement of the Problem

This study derived from a needs-analysis performed with sixth semester students (of the BA in bilingual education program of a private university in Bogotá, Colombia) who were training to write academic essays for an international exam. At the beginning of the semester, the teacher did a series of observations that led to identifying students’ lack of skills at the moment of writing essays. She also found that students’ writing practice in their English classes was limited exclusively to narrative texts, which made it difficult for them to meet the academic standards for writing sections on international tests. The lack of practice and training in this area unveiled a lack of proper argumentation, weak cohesion and coherence, improper paragraph formats, Spanish-like structures, and inaccurate conclusions, among other aspects.

In order to target these issues, the teacher collected students’ initial reflections about their academic writing needs, which allowed us to have a clearer insight in terms of the students’ perceptions regarding their writing processes. Such insights included the need for a more critical role by deeply analyzing the challenges the students faced during the steps of the pedagogical implementation and their own performance through formative feedback and self-assessment.

We used students’ reflective journals, teachers’ feedback, and students’ self-assessment regarding the process of writing an academic text. We encouraged students to work on reflective learning as they wrote journals after each of the stages they developed, and to include thoughts about their planning, learning, and self-regulated actions to foster metacognition through monitoring and control (Nelson & Narens, as cited in Dunlosky et al., 2016).

We considered the relevance of learners’ constant self-assessment since it helps teachers and students identify to what extent they have achieved their learning goals. Furthermore, it helps teachers evaluate their own practices to support the learners’ process (Palomba & Banta, 2001). Likewise, formative feedback plays a meaningful role as it provides students with the opportunity to analyze their performance and put this analysis into work when improving their skills.

Literature Review

In order to carry out this study, we reviewed literature concerning the main constructs that supported our pedagogical implementation. In this sense, we focused on reflective learning, academic writing skills, indirect and formative feedback, self-assessment, and metacognition, which are described in the following paragraphs.

Reflective Learning

Reflective learning is defined by Rickards et al. (2008) as the “intentional use of reflection on performance and experience as a means to learning” (p. 33). Accordingly, there are three stages to effectively implement reflective learning (Scanlon & Chernomas, 1997, as cited in Thorpe, 2004). First, there is awareness, which refers to the acknowledgement of the discomfort, lack of information, situation, or event that fosters students’ inquiry during the learning process; second, the given phenomenon that is the center of the reflection requires a critical analysis, which at the same time needs skills such as self-awareness, description, synthesis, and evaluation for it to be properly developed; and finally, a new perspective, which emerges after the phenomenon has been critically analyzed. In short, these stages allow both teachers and students to include systematic and meaningful reflective practices inside the teaching and learning processes.

Because the purpose of reflection as a pedagogical tool is to establish connections among cognitive and experience-related elements (Jordi, 2011), reflective learning offers teachers and students two relevant tools that encourage proper reflective practices. First, Xie et al. (2008) establish that journaling offers the space for students to externalize their reasoning and reflections on experiences they consider relevant for their learning process. Second, Moon (2013) states that collaborative work facilitates reflection since it offers an external perspective towards the analyzed situation. Once reflection is part of both students’ and educators’ practice, it lays out possible solutions to learning and teaching issues, leading to the transformation and integration of new understanding within the classrooms (Rogers, 2001).

Academic Writing Skills

Learning to write academically is one of the many issues EFL and English as a second language learners face. This field conveys specific challenges given the rigor that this practice poses, along with the fact that foreign language learners are faced with linguistic characteristics distant from the linguistic traits their first language has. In this sense, we will refer to particular skills we consider relevant for our students’ process, since they enable them to find their own voice and increase their English proficiency not only when writing, but throughout all the skills and the literacy-driven processes.

In order to address academic writing tasks effectively, we focus on style and correctness. Sword (2012) proposes style as the writers’ capacity to tell a compelling story while keeping the reader’s attention with information that is both engaging and scientifically supported. Developing style depends on how writers approach the language and the different linguistic components they are able to successfully implement in their texts. Most of these components are part of the structural and lexical skills, which combined give the text a sense of “correctness” or the ability to involve grammar, punctuation, spelling, and referencing to structure proper texts (Bailey, 2015; Elander et al., 2006). Accuracy is also necessary when writing any sort of text (Ivanič, 2004).

The previous skills will enable EFL learners to develop their academic literacy while understanding its components (Warren, 2003). In effect, being academically literate implies learning “the specialized practices of academic reading, writing, and speaking that characterize college-level communication” (Curry, 2004, p. 51).

Indirect and Formative Feedback

Feedback is a way to assess how well pupils’ performance was (Harmer, 2007). It can be classified as direct, with a correct version provided to students, or indirect, when errors are indicated, but not corrected by teachers (Westmacott, 2017). Hendrickson (1980) used indirect correction-coded and uncoded-by indicating the location and types of errors when he assumed learners could correct them on their own. Research has shown that indirect error feedback is more beneficial since it increases students’ engagement and attention to problems and forms found in their written production (Ferris, 2003), and it helps learners achieve more accuracy than those who received direct corrections (Chandler, 2003). Westmacott (2017) found that motivated learners who valued metacognitive knowledge of grammar favored indirect coded feedback as they became active actors in their writing process by strengthening their grammar knowledge and developing autonomous learning patterns.

Moreover, the main aim of formative feedback is to transform thinking and behavior to increase students’ knowledge and understanding of some content area or general skill (Shute, 2008), based on specific standards (Bollag, 2006; Leahy et al., 2005). According to Narciss and Huth (2004), effective formative feedback should take into account the instructional context and the learners’ features; when designed systematically, factors that must be considered are the instruction (objectives, tasks, and errors), the learners’ information (goals, prior knowledge, skills and abilities, and motivation), and finally, the feedback itself (content, function, and presentation). The usefulness of this type of feedback relies on the fact that it should be needed, timely, feasible, and desired. Likewise, it must attempt to revise different aspects, such as learners’ outcomes, the process involved, and the level of improvement (Shute, 2008).

Self-Assessment

Self-assessment implies pupils reflecting on the quality of their work so that they can judge whether they have achieved their goals and revise their performance accordingly. This is possible through the elaboration of drafts that can be revised and improved. The main goal of this kind of assessment is to boost learning by giving timely feedback on pupils’ comprehension and performance (Andrade & Cizek, 2010).

Self-assessment involves three steps: The first one is articulating expectations for the task or performance; this is done by teachers and students separately or together when checking examples of an assignment or creating a rubric. The second stage is the critique of work based on expectations, so learners draft and monitor their progress by comparing their performance to the expectations. The last step implies revising; thus, students use the feedback from their self-assessments to guide a revision. This is fundamental because students self-assess thoughtfully if they know that their work drives them to improve (Andrade & Cizek, 2010).

Metacognition

Metacognition refers to “knowledge and cognition about cognitive phenomena” (Flavel, 1979, as cited in Dunlosky & Metcalfe, 2009, p. 32), whereas scholars such as Martinez (2006) have referred to it as “thinking about thinking.” As a cognitive process, it is composed of several components and skills, which we will briefly address from two different perspectives: from the main metacognitive categories and from a metacognitive framework standpoint.

Regarding metacognitive categories, Martinez (2006) establishes three: metamemory and metacomprehension, problem solving, and critical thinking. Metamemory refers to how well you recall your knowledge, whether you remember a fact or not, while metacomprehension refers to the reflective process you go through regarding your knowledge, whether you know or understand something or not. As for problem solving, it is understood as the pursuit of a goal when the path to it is uncertain: being able to understand a phenomenon, identifying the necessary procedures to address it, and developing and implementing different strategies to overcome the given situation. This category in itself requires other activities such as generating and weighing possibilities, exploring subsets of options, and evaluating the results. Finally, critical thinking is defined as “evaluating ideas for their quality, especially judging whether they make sense or not” (Martínez, 2006, p. 697).

From a metacognitive framework point of view, authors such as Nelson and Narens (as cited in Dunlosky et al., 2016), and Serra and Metcalfe (as cited in Negretti, 2012) established three perspectives from which metacognition is developed: awareness, monitoring, and control. In the first instance, Dunlosky and Metcalfe, and Serra and Metcalfe (as cited in Negretti, 2012), establish awareness, in terms of metacognitive processes, referring to three main aspects:

(1) declarative knowledge, or awareness of what strategies and concepts are important in relation to a specific task, (2) procedural knowledge, or awareness of how to apply concepts and strategies (how to perform the task), and (3) conditional knowledge, or awareness of when and why to apply certain knowledge and strategies (p. 145).

Monitoring, on the other hand, refers to all the activities we do when we are evaluating our own learning. In this regard, judgements on the things one learns and how well or easily one learns them are paramount in order to feel confident, which will lead the process towards self-regulating actions taken after the monitoring stage, known as control. Moreover, Monitoring poses a great challenge for learners’ metacognitive processes, since it is the first sense of “feeling-of-knowing” (Hart, as cited in Perfect & Schwartz, 2002) they have. This “feeling” entails learning to judge whether one is learning or not, and what actually helps one do so.

Method

Research Design

This research follows a qualitative approach, which allows one to explore a phenomenon by interpreting the participants’ behaviors, values, and beliefs, among others, inside their context; thus, enabling different ways of “seeing the world” (Atkins & Wallace, 2012; Bryman, 2012; Packer, 2011). Likewise, we followed an action-research design because it addresses and attempts to solve a real-life problem (Creswell, 2012).

Setting and Participants

Our research took place in a private university in Bogotá. The participants were 15 EFL preservice teachers of a bachelor program who were studying the 6th level of English. They had to be prepared to take English standardized tests and so, they needed to develop academic writing skills to compose an opinion essay.

Pedagogical Implementation

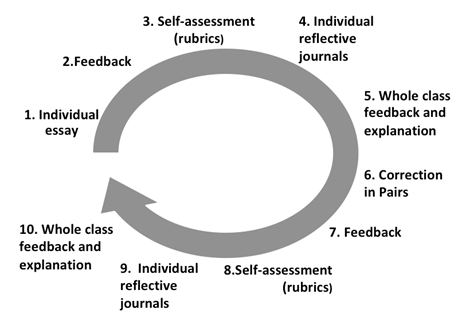

This study took place during an academic semester in which students had to work on all their EFL skills, therefore, fostering writing skills for taking a standardized test was part of it. The semester was divided into three terms, so we replicated the pedagogical implementation cycle (see Figure 1) the same number of times.

First, students wrote a draft of their opinion essays, then we provided them with indirect feedback and set some class time to discuss their performance. Then, the students received a rubric (from Educational Testing Service, 2019) corresponding to the standardized test for them to self-assess their documents. Afterwards, we asked students to write a reflective journal entry and guided them with some questions that pointed to their performance, learning, flaws, and actions to be taken. Once they finished, the teacher read the reflections and prepared a session of feedback and explanation for the whole class, addressing the points they had marked as relevant to be clarified. Thereupon, the students worked in pairs to correct the essays each member had written at the beginning of the cycle. Once more, they received indirect feedback in class and assessed their performance based on the rubrics given. Then they wrote another individual reflective journal entry which provided the teacher with topics to work on during a second whole class feedback and explanation session. This cycle was repeated three times and provided several insights regarding the learners’ academic writing skills.

Data Collection Instruments

In order to collect data, we used mainly non-observational data collection techniques, particularly students’ essays, which included the teacher’s indirect feedback, a rubric suggested for independent writing tasks (Educational Testing Service, 2019) that students used to self-assess their productions, and their reflective journals. Eventually, such instruments allowed us to have a closer insight in terms of students’ academic writing in our classes.

Through the teachers’ feedback on essays, we could see the characteristics of students’ manuscripts, the strengths and weaknesses the students exhibited in terms of style, accuracy, and correctness as well as how their writing skills were being shaped. The rubric they used for self-assessment revealed to what extent they considered they had reached their learning goals comparing them to the standards required. Students’ reflection journals allowed us to have a clearer idea in terms of what they perceived about their performance, their main goal, the feedback they had received, the discussions they carried out among peers, the difficulties they had faced, and the changes they considered necessary as well as the possible strategies they wanted to apply for improvement.

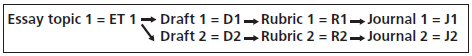

In order to systematize the data, we used the following codification: The participants were codified assigning the letter S and a number from 1 to 15 and the three cycles are represented as C and the corresponding number (see Figure 2). As students worked on a topic essay per term, every paper was coded as ET and numbers 1, 2, and 3. Besides, the students wrote two versions of every essay; so these drafts were coded with letter D and numbers 1 and 2. Participants’ rubrics and journals were coded as R1 and R2 and J1 and J2 since they worked on a rubric and journal per draft.

Data Analysis and Discussion

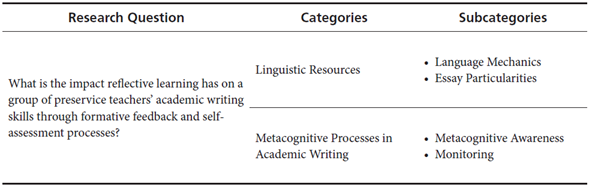

The data collected were analyzed through the methodological triangulation of sources (Bryman, 2012). The analysis followed the processes of the grounded theory approach, which follows an inductive process through a systematic analysis of data in order to characterize what is happening in a specific context and generate theory (Bryant & Charmaz, 2007). After examining the information gathered, we started to categorize the data according to the research question. Subsequently, two categories and four subcategories emerged based on the research inquiry (see Table 1).

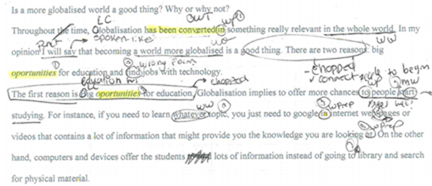

Linguistic Resources

The implementation of the pedagogical cycle in this study required students’ essay drafting to foster their academic writing. There were two drafts per each of the three cycles that were carried out. Once students submitted their drafts, the teacher provided indirect feedback by using proofreading marks (see Appendix) that were established and socialized at the beginning of the semester. Based on the correction of these texts and the systematization of proofreading marks from the final drafts, it was possible to identify the types of mistakes that were frequent in terms of language mechanics and essay particularities.

Language Mechanics

The term language mechanics refers to elements that help a text reach a level of organization and style according to academic standards. It includes aspects such as spelling, vocabulary, grammar, and syntax, among others, which, if used properly, characterize skillful writers by showing better control over the language (Crossley & McNamara, 2016). For this study, it was important to identify to what extent these elements, from the students’ written drafts, reached the standards required for an academic text, specifically, an opinion essay. In this regard, we aimed at supporting students’ grammatical development by means of teacher’s feedback.

In order to describe the process of improvement that students evidenced regarding this aspect, we focused on the teacher’s indirect written feedback provided for the final drafts of every cycle, which allowed us to identify mistakes and report them with the use of proofreading marks. As found by Kang and Han (2015), written corrective feedback tends to have a positive impact on grammar accuracy. Therefore, by providing formative and indirect feedback, we found some changes along the learning process. Additionally, the different learners’ reflections regarding elements of language mechanics demonstrated their awareness concerning the types of mistakes they made, which confirmed the weaknesses we had identified.

At the beginning of the process, several elements related to language mechanics mistakes were evidenced. Regarding the production from the first cycle of the implementation (a draft and final paper) through indirect written feedback, we noticed a high frequency of mistakes in terms of punctuation, wrong word, spelling, Spanish-like forms and wordiness, and a not so frequent display of mistakes related to verb forms and missing word (see Figure 3).

The rubrics students used to assess their papers and our systematization of the text proofreading marks also showed students’ awareness regarding these elements. After counting the different kinds of mistakes students made, we identified many of them as being related to word choice and structures. Sixty percent of the students marked their papers as 2 out of 5, a score that corresponds to a clear difficulty to choose words and forms and a large collection of mistakes regarding elements of language mechanics. Likewise, students’ journals included reflections upon their fears concerning this type of written tasks and the mistakes they considered were affecting their texts the most.

Excerpt 1.

I feel a little bit nervous because I don’t have the security to write. (S5, J1, C1)

During the second cycle, the students’ productions unveiled a radical improvement in most of these aspects, demonstrating a very low frequency of mistakes related to spelling and Spanish-like forms and wordiness, followed by a relatively low frequency of flaws regarding verb form and missing word. However, there was a very high occurrence of mistakes related to wrong words and punctuation, which was confirmed by the students’ reflections in which they identified the necessity to work on punctuation and vocabulary, mainly academic, and look for synonyms; their self-assessment also changed as their marks improved. The lowest score was 3 out of 5, which was the one two groups chose to assess their papers. Four groups marked their paper as 4 out of 5, and a group decided they had reached all the standards and self-evaluated as 5.

Excerpt 2.

Vocabulary, because sometimes I made a translation of the sentences. And the English is different to Spanish language. (S1, J2, C2)

Excerpt 3.

I need to learn more words and adjectives and adverbs mainly of degree. (S4, J1, C2)

Excerpt 4.

I need to work grammar connectors, punctuation, synonyms. (S6, J2, C2)

However, for the final cycle, elements of language mechanics evidenced another change. Some aspects that in the second cycle had improved, suffered an involution. The students’ texts presented problems, mainly, in terms of wrong word choice, followed by punctuation, spelling, verbal forms, wordiness, Spanish-like constructions, and missing words. Something to highlight is that the students’ reflections were not focused on elements of language mechanics, although a few of them mentioned their necessity to work on grammar, punctuation, and vocabulary; it seemed that they were more focused on aspects concerning the academic text structure. Likewise, their self-assessment process resulted in lower scores, as four groups graded their papers as 4 out of 5, two as 3 out of 5 and a group got 2 as the lowest score. Thus, this final report evidenced that students had lost focus on linguistic resources; although they seemed to consider the relevance of accurate texts, their efforts were not enough to meet the standards in these aspects.

Nevertheless, comparing the results from the first and the last cycle (see Figure 4), it was possible to identify an improvement in most of the aspects related to language mechanics, as the number of mistakes decreased, except for the use of wrong words, which constituted an important aspect to keep working on.

Overall, language mechanics represented a relevant aspect at the moment of writing academically. Through the implementation of this research, we could see an improvement comparing the final drafts of the first and the last stage. The learners’ academic writing evidenced a much higher text quality in terms of spelling, Spanish-like structures, and punctuation, followed by a moderate improvement in verb forms, missing words, and wordiness. Conversely, the use of wrong words did not present a clear reduction, which shows that learners need to continue working on vocabulary. This was supported not only by the statistics, but also in the reflections the students wrote in their journals.

Essay Particularities

The students had to write a personal experience essay in accordance with the independent task of an international exam with particular characteristics regarding topic development, organization, and clarity. In relation to topic development, raters will be looking for an introduction that clearly expresses whether the author agrees or not with the statement provided, which is the topic that must be developed in the essay, and explanations of key points through examples and details. The raters will assess the essay organization and clarity based on the structure developed; thus, responses should include an introduction, body paragraphs that introduce clear key points, a conclusion and transitions that contribute to the unity, progression and coherence of texts (Practice test pack for the TOEFL test [HarperCollins UK, 2014]). For this study, we focused on the main structural aspects that would help students to write this kind of academic compositions; so we checked that every essay included background information; a thesis statement; body paragraphs made up of topic sentences, supporting ideas, and concluding sentences; and a main conclusion at the end of the essay.

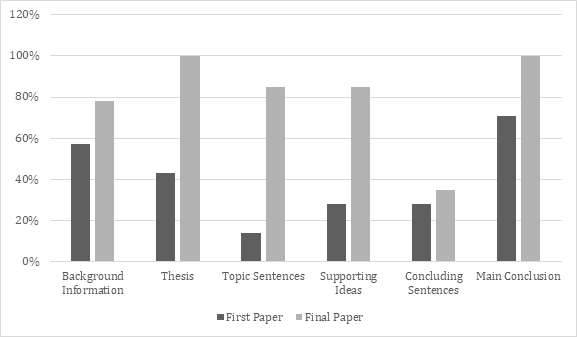

At the beginning of the semester, the abovementioned aspects were in need of improvement. In the first essay students wrote, only 14% of them included topic sentences in the body paragraphs and only 28% wrote supporting ideas and paragraph conclusions. Seventy-two percent of the participants failed to include thesis statements and 47% omitted proper background information in the introductions. However, 71% of the students were able to conclude the essay despite the missing elements mentioned above. We understood these first challenges as the beginning of an ongoing process, since writing practice is a procedure that involves continual and constructive feedback on written work (Bitchener, 2008).

At the end of the academic semester, there was a significant change in the learners’ written production based on their performance in the last essay submission (see Figure 5). All the participants managed to include thesis statements and main conclusions. Additionally, the most remarkable improvement was evidenced in 85% of the students, who consistently wrote topic sentences and the corresponding supporting ideas in their papers. Background writing also improved since 78% of the essays had these sentences to catch the reader’s attention. Nevertheless, participants kept omitting concluding sentences, so 65% of them failed to wrap up the ideas of body paragraphs. The students’ performance confirms that providing feedback may help students recognize and avoid errors when they submit corrected versions of their compositions based on the comments they received (Ashwell, 2000). Likewise, we could observe how self-assessment resulted in observable improvements in the quality of essays (Fung & Mei, 2015).

These results unveil how the sequence we proposed with different steps of feedback, reflection, self-assessment, and multiple drafting had an impact on the students’ performance and contributed to their awareness of the essay structure for an international exam. Although most of the essay particularities were enhanced through this cycle, writing is quite a demanding process that requires more time in order for the writer to accomplish the standards required for this type of text.

Metacognitive Processes in Academic Writing

When students have the possibility to learn reflectively, they understand the importance of developing strategies and learning processes that allow them to achieve their learning goals properly. In this case, the data showed our students’ different metacognitive features as they started to improve their academic writing. Such traits relate specifically to the initial awareness they began to display regarding the actions needed to enhance their writing skills and the monitoring actions they started to implement.

Metacognitive Awareness

During the observations of our students’ writing processes, we could notice they showed “awareness,” concerned with their weaknesses and, consequently, proposing possible strategies to improve them. In this stage, students’ reflection showed the fact that they had indeed identified some aspects to improve their academic writing, thus evidencing their declarative knowledge (Dunlosky & Metcalfe, and Serra & Metcalfe as cited in Negretti, 2012). In this regard, some of their comments are:

Excerpt 5.

I feel afraid because I have spelling problems and also, I have to think a lot in order to understand something coherent. (S7, J1, C1)

Excerpt 6.

I need to find more resources to support my future essays. Besides, I need to increase my vocabulary. (S11, J2, C1)

As evidenced in the excerpts above, students had the opportunity to reflect upon their process, particularly during the first stage once they received the teacher’s feedback and were asked to edit their manuscripts. Some of the aspects most students felt they needed to work on were related to vocabulary, grammar, and punctuation. Indeed, their reflections about the areas they felt they needed to improve upon represent their declarative knowledge, since these reflections are related to their understanding of writing academically.

Therefore, once students started to identify the aspects they needed to work on, thanks to the self-editing stage they went through, they started to come up with possible actions and strategies that they could put into practice (Negretti, 2012). This process is closely related to the concept of procedural knowledge, in which learners are expected to identify strategies and procedures that will allow them to achieve their cognitive goals. As such, our students expressed their procedural knowledge by proposing the following strategies:

Excerpt 7.

I need to write more about educative things. I have to practice on my writing and punctuation. (S4, J1, C1)

Excerpt 8.

Correct the mistakes in this essay to understand things that I didn’t know before. (S2, J2, C2)

Excerpt 9.

I will give my essay to other person, in that way he or she is able to give her or him feedback and I will have a second opinion. (S10, J1, C2)

Excerpt 10.

I want to practice and write more frequently. Also, I need to review the teacher’s presentation. (S11, J2, C2)

Excerpt 11.

I am going to read some academic essays. (S5, J1, C3)

Excerpt 12.

Self-correction, after having pointed out the mistakes, it’s a great way of learning how to write properly. (S12, J2, C3)

As can be observed, most of the strategies proposed by the participants were directly related to self-editing (Excerpts 14 and 18), peer editing (Excerpt 15), practice (Excerpts 13 and 16), and modelling (Excerpt 17). From Murray and Moore’s (2006) and Murray’s (2013) perspectives, drafting and revising the draft (actions considered under the category of self-editing) are key strategies when it comes to having a fresh, more elaborated perspective about what is being written, which constitutes the first feedback we receive. Once this self-editing process is done, writers can move on to the next stage, which is asking for external feedback or peer editing; this enables dialogue and creation of academic community (Murray, 2013). As for practice and modelling, students themselves considered that writing more often and reading other academic texts enabled them to understand grammar structures better in order to reproduce them in their own texts. As such, practices such as the previously mentioned evidence the close relationship between modelling and reflective learning (Loughran, 2002).

Consequently, thanks to the reflective learning activities carried out by the students, their awareness regarding their writing process was observed. As such, being able to identify the aspects they considered needed improvement encouraged them to propose actions and strategies to face said areas in need.

Monitoring

Once students’ metacognitive awareness was fostered through reflective learning, we had the opportunity to identify the strategies they considered were necessary to improve their academic writing. Through this, it was important to foster said strategies and assess whether they were working or not. This process is called “monitoring,” which Nelson and Narens (as cited in Rhodes, 2019) relate to assessing and evaluating one’s learning.

In Figure 6, we can observe the process through which students managed to assess or monitor their writing process.

First, students developed individual initial drafts of their essays, and then they received indirect written feedback from the teacher. In Figure 6 we can observe mechanics and content areas that the students addressed for improvement. This information constituted the source for them to self-assess their performance.

Since students were polishing their academic writing skills in order to present international exams, we used a specific rubric in order to self-assess their papers (from Educational Testing Service, 2019). This tool enabled both teacher and students to have clear criteria regarding the writing process. Once students carried out their self-evaluation, they reflected on four aspects: the planning of the essay, the new learning they had reached after the feedback received, their reactions towards feedback, and the actions that would be taken in order to improve their writing skills, which represented the strategies they manage to propose. As the classes moved on and we established the strategies students offered, learners started to monitor their self-editing and peer-editing actions, which were the most common strategies that they proposed during their awareness stage.

After that, the teacher offered the learners feedback and general explanations regarding the writing process. Eventually, after revising and editing in pairs, we could observe the improvement of their writing performance:

Excerpt 13.

A class is successful when you have a good relationship with students. Therefore, I agree with the idea of giving importance to the teachers’ ability to relate well to the students more than the knowledge of the subject that is being taught. I believe this for two reasons that will be explained in the following essay. First, knowledge has no value if the teacher does not know how to transmit it, and second, students will enjoy the class much more if they have a great relationship with their teacher.

Thus, once they received the teacher’s new feedback, and analyzed the level of their performance, a new process of self-assessment took place, which consequently helped them increase the score obtained in the previous version of their text. Therefore, students’ reflections during the process led them to implement monitoring strategies as part of their metacognitive strategies. When they applied the actions they saw as necessary in order to improve their academic writing skills, they were able to carry out a more in-depth editing process. All in all, through metacognitive awareness and monitoring, students had the opportunity to take control of their own learning process. In this sense, learning and understanding the areas they needed to work on, and establishing strategies they considered relevant for their improvement, empowered them to enhance their writing skills.

Conclusions

This study focused on the impact of reflective learning on a group of EFL preservice teachers’ academic writing skills through formative feedback and self-assessment. We could identify two main areas in which the impact was visible: linguistic resources and metacognition.

Regarding linguistic resources, we could identify that this implementation favored the learners’ writing skills by means of indirect, formative, written feedback, multiple drafting, working in pairs, and reflecting upon their performance. First, the learners identified their language mechanics weaknesses; this provided opportunities to review grammatical aspects, punctuation rules, and assertive vocabulary, among other relevant items of working on any writing task. At the end of this implementation, the learners wrote more accurate texts, which evidenced a more conscious use of language mechanics and, in turn, helped them develop editing skills. Second, they were able to identify the particularities that build up an academic text such as an essay. Being aware of the essay structure allowed the learners to incorporate gradually all aspects they did not include at the beginning of the implementation. Their understanding of most of the essay components nurtured the quality of their essays in order to meet the requirements for international exams.

Nonetheless, there was an unexpected phenomenon during the implementation. Aspects that seemed to have improved after the second cycle tended to appear again during the last one, although we could still appreciate clear improvement between the first and the final papers. Thus, we could notice that when students centered more on the structure of the papers, they lost focus on the language mechanics. Likewise, we acknowledged that there was an evident gradual incorporation of the essay structure, which, supported by the students’ reflections, let us conclude that they were more concerned about the structure of an international exam that was new for them.

As for metacognitive features, we had the opportunity to evidence two outstanding characteristics. On the one hand, we identified students’ awareness when it comes to the needs and gaps they presented in regard to their writing skills; which included actions such as peer and self-editing, practice, and modelling. On the other hand, there were monitoring procedures carried out by both the teacher and the participants in order to assess students’ actions that let them improve their manuscripts; the procedures that students commonly used were peer and self-editing. On this basis, reflections made by our students allowed us to observe and evidence the process students went through and, consequently, the improvements they portrayed in their papers.

Overall, improvement of linguistic resources and development of metacognitive features constituted the main impact of this pedagogical implementation. However, time seems to be an issue as it is necessary to devote more lessons to give continuity to this process and be able to achieve better results.

Limitations and Pedagogical Implications

There were some limitations we could identify. Firstly, time was an issue since the target group had six academic hours a week; it would be necessary to devote more lessons with a higher frequency to give continuity to this process and achieve better results since, as mentioned by Karim and Nassaji (2019), the effect of feedback should be studied over a long period of time. Secondly, students seemed to be very focused on the structure of a standardized essay as they were going to finish their cycle of English levels proposed by the curriculum and also as their future classes implied the use of this type of text. Therefore, whenever they received feedback, they centered their attention on essay particularities, and overlooked language mechanics aspects. This affected the expected results on the final versions as feedback does not guarantee learners’ final decision-making; this is one of the aspects that may interplay when correcting their written production. Likewise, we agree with Karim and Nassaji since we consider language accuracy is one of the many aspects that learners must focus on to become successful writers; they also need to communicate and present ideas appropriately according to academic standards. Thus, one direction for further research is to analyze which factors may affect preservice teachers’ effective response to feedback.

Regarding implications, we highlight the necessity to write academic texts as a learning goal along the curriculum and feedback as a potential strategy for preservice teachers to develop writing skills. This may progressively help students master this type of text and its features while developing their editing skills, gaining academic vocabulary, expressions, and structures and developing metacognitive awareness.