Introduction

Foreign language teaching has become a challenge for both urban and rural schools in Colombia because national foreign language policies and requirements are rigidly uniform in the entire country. There is no consideration of geographical or cultural identities, which are quite distinct from one another. Rural schools are at a particular disadvantage as they must meet the requirements without sufficient human, pedagogical, or technological resources (Cruz-Arcila, 2017).

In the midst of these conditions, language teachers can utilize pedagogies that connect places and communities with their classroom practices. These pedagogies seek to consider the individuals and their capacity to position themselves within the realities in which they live, and to involve teachers in an exploration of the richness of their surroundings as possible sources for their pedagogical constructions. Teachers can draw on community-based pedagogies (CBP) which are grounded in critical pedagogies that transform their daily realities into possible pedagogical sources for teaching and learning. Critical pedagogy has been central for teachers who want to promote changes in students and their communities (Hernández-Varona & Gutiérrez-Álvarez, 2020). According to Wink (2009), “critical pedagogy is a process that enables teachers and learners to join together in asking fundamental questions about knowledge, justice, and equity in their own classroom, school, family, and community” (p. 71). In this sense, teachers and students can become agents of change as they undergo a process of discovering possibilities that can be explored in the classroom and make decisions to transform the many alternatives presented to them into tangible actions that work to their advantage. The notion of agency is also in line with critical pedagogies in the sense that individuals are able to evaluate their realities and make decisions to initiate transformations in understanding who they are, in other words, their identity. As Duff (2012) states, agency refers to the capability to make decisions, self-regulate, and strive for a common goal leading to personal or social transformation.

This article responds to one of the research questions that led to our study: How do students enact agency as a result of exploring their rural communities and their rural identity? In this respect, this report illustrates the way in which learners enacted agency after exploring their communities and viewing themselves as uniquely situated as farmers from a rural area. From that perspective, they were able to make local connections with global environmental concerns and social situations experienced every day in their hometowns. English was used as a means of instruction and communication to carry out class discussions and project activities. CBP became also a source to enact agency and raise students’ awareness of their rural identity. Besides, we present a brief theoretical revision of the main concepts that support this study, describe the context in which it was carried out, and the results of experiencing CBP with this group of learners.

Theoretical Framework

The concepts that support this study are related to critical pedagogy, CBP, and agency in that they conceive learning as situated and call teachers to focus on all the resources a particular place can have, as well as the features rural identity can offer teachers to make curricular decisions and unveil new sources of knowledge.

Critical Pedagogy

In this study, learning is understood as situated and particular; that is why critical pedagogy recognizes that learners exist in a cultural context and in a particular place, hence its importance for our study. Freire (as cited in Grunewald, 2003) states that people are rooted in temporal-spatial conditions that make them reflect on their “situationality” to the extent that they have to act upon it. In other words, it is not possible to belong and move in a place without reading it and becoming aware of its realities and being moved into action on behalf of that space in which people exist.

Mahmoudi et al. (2014) argue that in critical pedagogy schools are regarded “as places for social change and evolution. They should not only foster critical thinking in students, but also teach them how to change their surroundings” (p. 86). For McLaren (1998), teachers, parents, students, governments, and school communities play a significant role in the learning process. For this process to be effective, they need to be aligned in order to reach the same goals, to achieve equity and justice in education. In this respect, McKernan (2013) claims that critical pedagogy “is a movement involving relationships of teaching and learning so that students gain a critical self-consciousness and social awareness and take appropriate action against oppressive forces” (p. 425). Such an approach should enable students and teachers to enact agency through investigating and understanding their contexts and identifying possibilities for change, which will require decision-making and action.

Community-Based Pedagogies

CBP principles are rooted in foundations of critical pedagogy and give shape to a form of pedagogy in which teachers and learners can nurture learning that occurs locally, and which conceives of the environmental space as a primary resource for pedagogical decisions. As Grunewald (2003) states, “place-based pedagogies are needed so that the education of citizens might have some direct bearing on the well-being of the social and ecological places people actually inhabit” (p. 3). From this perspective, learners are able to envision their own realities and to act accordingly in a critical and agentive way.

Demarest (as cited in Clavijo-Olarte & Ramírez-Galindo, 2019) urges teachers to design the curriculum based on local inquiry and to explore places as texts to promote local research. Teachers are called on to discover all the resources local places can offer for their classes, to construct content that is relevant and close to students’ communities, and to challenge students to explore their living environments through inquiry to develop ideas that might contribute to their local settings.

Of course, this is not an overnight change, “it is a forward motion that teachers become engaged in as they explore their communities with their students and discover the amazing and sweet opportunities for learning and living in community” (Demarest as cited in Crosby & Brockmeier, 2017, p. 78). CBP represents a challenge for teachers with respect to evoking reflection on the relationship between the type of education they want and the places they inhabit and are leaving for new generations (Clavijo-Olarte & Ramírez-Galindo, 2019). Sharkey and Clavijo-Olarte (2012) understand CBP as “curriculum and practices that reflect knowledge and appreciation of the communities in which schools are located and which students and families inhabit” (pp. 130-131). Whether in the city or the countryside, teachers need to develop a deep understanding of their communities, make connections between the school, its people and places. In other words, these teachers are “educators who actively research the knowledge of the cultures represented among the children, families, and communities in which they serve . . . as a means of making meaningful connections for and with children and their families” (Murrell, 2001, p. 51).

Agency

Location-based learning enhances agency in the sense that students can enact engagement, social responsibility and community cohesion. They became empowered and developed a sense of achievement (Crosby & Brockmeire, 2017). For van Lier (2010) “agency refers to the ways in which, and the extents to which, the person (self, identities, and all) is compelled to, motivated to, allowed to, and coerced to, act” (p. 10). This means agency comes from a desire or will to make something happen to a certain degree. In like manner, Duff (2012) refers to agency as “people’s ability to make choices, take control, self-regulate, and thereby pursue their goals as individuals, leading potentially to personal or social transformation” (p. 417). Coincidently, Muramatsu (2013) declares that “a sense of agency enables individuals to make choices with regard to how they relate themselves with the social world, to take ownership in the pursuit of the enterprises in their lives, and to create opportunities for self-transformation” (p. 62). This position suggests that agency is the power to make decisions that lead to accomplishments and social or individual transformation. Similarly, for Carson (2012) agency “may be understood as an individual (or collective) capacity for self-awareness and self-determination: decision-making, ability to enact or resist change, and take responsibility for actions” (p. 48). In this respect, CBP opens the door to explore communities and to involve students in a process of reading and understanding their local surroundings, identifying events they feel connected to and proposing concrete actions that involve decision-making processes that benefit the community in which they live.

In relation to foreign language teaching, Cruz-Arcila (2018) argues that the teacher’s role is to create connections between language and culture as a way to establish links with the values of the community. Bonilla and Cruz-Arcila (2014) discovered that students who lived in rural areas were more focused on farming with its emphasis on physical labor than on learning a foreign language. Consequently, the main goal of a teacher is to find ways to connect students’ realities with their classrooms. From this perspective, teachers become mediators between language, culture, and identity. They need to be aware of the students’ rural identities and find ways to connect them with classroom practices while using knowledge of students’ communities as pedagogical resources.

Identity

Burke and Stets (2009) define identity as “the set of meanings that define who one is when one is an occupant of a particular role in society, a member of a particular group, or claims particular characteristics that identify him or her as a unique person” (p. 3). It means that the individuals’ representation of their identity depends on their occupation, their beliefs, and even their roles in society. In this respect, local identity is established by the social contexts people are immersed in (Lin, 2009). Local identity entails several factors from culture and customs which end up constructing beliefs, traditions, and cultural practices from communities that are shaped by context realities (Flórez-González, 2018). Considering the concepts discussed, it can be inferred that local rural identity is tied to the activities that farmers and laborers do, their beliefs, their ways of doing their jobs, their understanding of the world, customs, cultural practices, and behaviors.

In Colombia, rural identities are connected to the previous concept where the identity of a farmer comes from the person who lives in rurality, works on a farm and holds responsibilities related to physical work on the land. In this respect, Llambí-Insua and Pérez-Correa (2007) declare rurality as places with low population density, the predominance of agricultural work, and cultural features different from those that characterize the population of the large cities.

The question here is, how to connect rural identity with language teaching? In this respect, Bonilla and Cruz-Arcila (2014), in their research about English language teaching in rural areas, bring important insights to the roles of teachers as builders of identity, where the language becomes “an end or action in itself that contributes to constructing and interpreting social and cultural reality” (Pennycook, 2010 as cited in Cruz-Arcila, 2018, p. 70). Their research illustrates that when teachers acknowledge students’ rural reality, they are able to make decisions that value and respect local knowledge.

The Study

This is a qualitative study rooted in an action research design that relies on a community inquiry project in which students’ surroundings were used as pedagogical sources. Action research is related to the ideas of “reflective practice and the teacher as researcher. It involves taking a self-reflective, critical, and systematic approach to exploring your own teaching contexts” (Burns, 2010, p. 2). In this respect, Kemmis and McTaggart (1988) argue that action research has three characteristics: First, it is carried out by the practitioner rather than outside researchers; second, it is collaborative; and third, it is focused on change and improvement. Smith et al. (2009) state that action research takes place when teachers carry out their own implementation in their own classrooms, evaluating the process and the results in order to bring about changes. Cano-Flores and García-López (2010) affirm that “action research is a form of knowledge construction conditioned by the necessary reflective exchange around theory and practice and by the continuous analysis of the educational reality” (p. 62).

Context and Participants

This study was carried out at a public school located in a small village about an hour and a half from Ibagué, a medium-sized Colombian city located in the center of the country. This is a coeducational school1 that has 196 students. Thirty-three students from ninth grade volunteered to participate in the study. They were actively involved in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of the project developed throughout the study.

Data Collection Process

CBP that worked as the pedagogical framework of this study also provided insights and forms of data collection. To begin the study, data were collected by the implementation of a needs analysis that allowed the teachers to identify students’ preferences, concerns, and suggestions in relation to their English class. After analyzing this information, the teachers and students selected the topics of interest. After that, the students were asked to do a photographic mapping of their communities, identifying possible issues or themes to explore throughout the project. The teachers then planned the project connecting the information provided by the students and the syllabus of the school (see the class planner in Appendix A). After three weeks of planning, the project was carried out during the second and third period of the school’s academic year (approximately four months). The students, guided by their teachers, explored their communities and carried out different activities focused on their identity as farmers and the realities they experience in their surroundings, as is evident in the class plan. Throughout the project implementation, there was a continuous process of reflection guided by the teachers and based on students’ performance. Dialogues and interviews served as tools to collect reactions from students and the original plan was modified in response to suggestions from students.

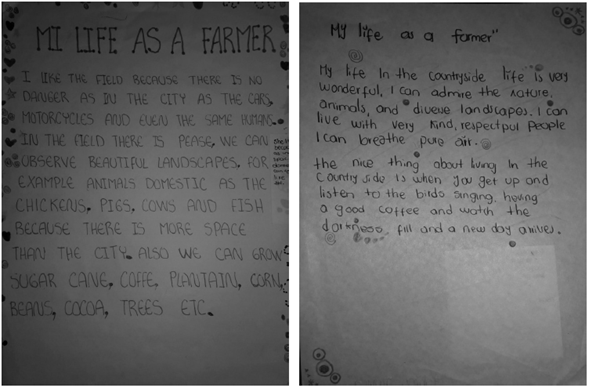

Data were collected by means of students’ artifacts that reflected the products students achieved throughout the project and their initiatives to benefit their communities (see Appendix B); a journal by teachers which contained reflections and insights after the different sessions with students; and narratives in which students wrote about their lives, activities, and customs as farmers, as well as perspectives about their communities (see Appendix B). Two additional instruments were the focus group2 that was carried out at the end of the process to hear the voices of students in relation to the project, and a class questionnaire, where students had the opportunity to give their opinions about the project and the classes (see Appendix C). Questions for these two last instruments were piloted with some students. Two action research cycles were developed during the study, each cycle including phases of exploring, identifying, planning, implementing, evaluating, and reflecting (Burns, 1999).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed and validated using triangulation and member checking. Member checking is a technique primarily used in qualitative research. According to Barbour (2001), Byrne (2001), and Doyle (2007), it is a quality control process by which a researcher seeks to improve a work’s accuracy, credibility, and validity (as cited in Harper & Cole, 2012). Lincoln and Guba (1986) refer to member checking as:

The process of continuous, informal testing of information by solidifying reactions of respondents to the investigator’s reconstruction of what he or she has been told or otherwise found out and to the constructions offered by other respondents or sources, and a terminal, formal testing of the final care report with a representative sample of stakeholders. (p. 77)

We first contacted students via WhatsApp and shared with them the findings and conclusions of the study through a PowerPoint presentation. They read and shared their reactions, which assisted us in verifying whether what we had said was accurate. The students then signed a letter in which they confirmed the credibility of the information gathered and presented in the study.

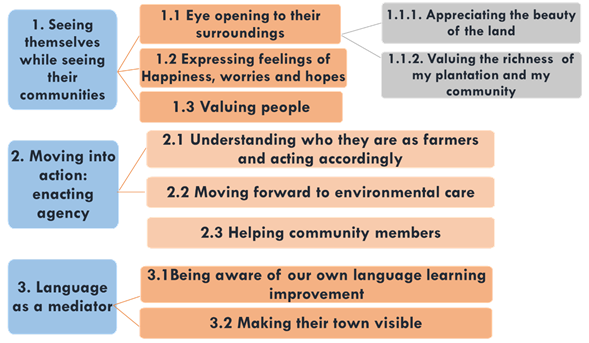

Data were analyzed under the principles of grounded theory. As Charmaz (2006) states, “grounded theory provides guidelines on how to identify categories, how to make links between categories, and how to establish relationships between them” (p. 10). First, the information collected through all the instruments was read several times in order to identify repetitive patterns and themes. Then, from these themes, preliminary categories were defined. After reviewing these categories, and in light of the research question, we defined the final categories and integrated them into concepts that sought to answer the stated research question (see Figure 1).

Although three categories emerged from the analysis, for the purpose of this article we will only focus on the second category: Moving Into Action: Enacting Agency, which entails three subcategories as described in the Findings section.

Findings

Understanding Who They Are as Farmers and Acting Accordingly

In the upcoming descriptions from student narratives, their deep love and appreciation for being farmers is evident:

I feel happy being a farmer because it has a unique nature. We get up with love to live the day, and we can see our crops grow each day. I liked all the activities that we did with the teacher and we could get to know all the different parts of the village. (Student 12, Narrative 1)

There are two aspects worth analyzing in this excerpt. First, there was delight in being a rural worker, where phrases such as “I feel happy being a farmer” displayed contentment with the uniqueness of the land. Second, the exploration allowed students to get to know the surroundings more intimately. The comment speaks to the advantages of being part of a rural area. The following excerpts illustrate the participants’ reasons for living in the countryside.

I feel very happy to live here because of my family, for the things we can learn from the countryside, and also for the great work that the farmers do to cultivate the land. Also, I feel very proud of the food we grow because we care about the environment and the people in the village help each other. (Student 7, Narrative 1)

My life in the countryside is beautiful because I have all my family here, I can share things and spend time with them, and see them constantly. There are various crops including sugar, plantains, avocados, yucca, corn, coffee, etc. (Student 21, Narrative 1)

These excerpts revealed the particular splendor of having a family in a rural area, which united and allowed them to be more connected with their family members. The land was also a reason of pride in which the abundance of crops and food is a blessing. Also, the expression “for the great work that the farmers do” stands out as recognition for the activities their community does and the products they cultivate. Throughout the implementation of the project, students explored their identity as farmers and displayed love and pride for their land. The following excerpt shows a deep feeling for belonging to a rural area:

After the activity I felt more proud of living in the countryside because I have the possibility to enjoy the tranquility of nature, to see beautiful landscapes, to live together with the environment and that my family is mostly farmers. (Student 19, Narrative 1)

This comment demonstrates how learners view their surroundings as something worthwhile, a unique place and a land full of beauty. This appreciative feeling of being farmers and their love and pride for the land and its people moved students into action. Once they made connections and expressed their realities, those feelings of affection became the motivation that enacted change. Their connection to the land and people caused them to contribute and care for the main resource, the land.

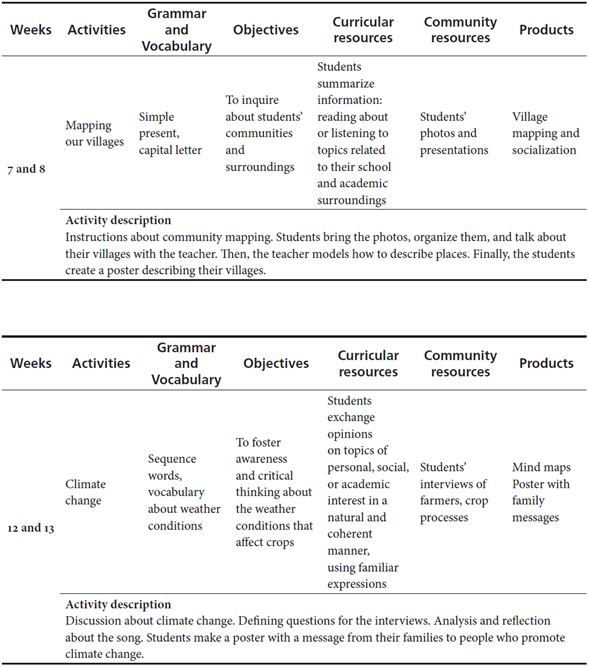

Moving Forward to Environmental Care

After observing the community, students were swayed to be aware of their surroundings. This subcategory relates the way students explored their locations, which allowed them to recognize the environmental issues that affected them, therefore triggering the desire to enact changes. When global warming was discussed in class as part of the project implementation, students were concerned about their current environmental situations. They reflected upon climate change as a threat to the places where they and their families reside and work since they grow grains, fruits, and grasses for daily sustenance. They managed to communicate their points of view in different ways, especially through mind maps (see Figure 2).

These mind maps reflect students’ various understandings of global warming and show how they integrated their contextual identities and resources, as well as how they saw and interpreted topics that were presented in English classes. Students were impacted by the global warming topic and its effects on their way of living. As seen in Figure 2, the participants started to discover where the environmental problems came from, how they perceived the effects, and what solutions could be devised in order to take action. Participants made the connection between global and local knowledge and evidenced agency processes in the decisions they made. They raised awareness about local risks with fires and climate changes and then designed posters in English, inviting families from their community to take care of the river and pick up garbage. Consequently, students found that taking care of their environment was also their responsibility, as the following excerpts show:

We could learn many things that I did not know before, for example global warming, and how we can help other people by planting trees. This experience was very thrilling because not only did we learn more about global warming, but also about the natural wealth of our village and its people. (Student 24, Narrative 1).

Students raised their awareness of the environment and the natural resources surrounding them. They reported learning something new on the topic of global warming and found in the target language a way to verbalize that learning. The expression “This experience was very thrilling,” highlights the impression the implementation made on them, not just because of the topic, as some students mentioned, but the realization that they were part of the problem and the solution.

Students made connections between the topics discussed in class related to climate change effects and the weather conditions they were facing in their village. They wrote very emotive messages after visiting and helping a family which had lost their avocado plantation. Seeing this family situation impacted learners strongly and moved them to a collective initiative. Both the students and the teacher planned a field trip to the property and helped the farmer and his family. This experience allowed learners to move from reflection and decision making to action. Visiting and helping a farmer was a way to connect what they discussed in class with the realities of what they saw in the real world. In the following excerpts, they expressed what they had learnt that had made an impression on them: “It impacted me because of the damage that fires can cause, and how these affected the mountains” (Student 3, Poster).

Students verbalized feelings and suggested alternatives in class using the target language. The vocabulary and language forms required for this purpose were worked on in class through language workshops as illustrated in the following quotes and the use of the modal verb “should”: “I learnt that we should take care of the environment by growing trees,” “I learnt that we should clean our villages and nature.” In these passages, “should” is used to express a moral obligation with nature, where planting trees, cleaning the towns, and caring about the land is a task everyone should be a part of. The use of the pronoun “we” included themselves and others as part of the solution. It showed how pupils, after taking part in actions, adopted new ideas and behaviors through sharing their messages with others.

In the same way, this feeling is reaffirmed in the teacher’s narrative about the students’ impressions:

It was meaningful for them to see why it is necessary to take care of the environment as it was really shocking for them to see the burnt mountains, because they had expressed worry about the environment; but with this visit they really could see the damage humans can cause to the land, and to the mountains where they and their families live and use what they need for living. (Teacher’s journal)

The teacher discerned her students’ feelings in the expression “meaningful for them,” representing what could be observed, the significance of the experiences, and how the activity impacted the students in their heart and minds. The teacher realized that this activity was not just another class exercise, but rather something that connected students with their realities and led them to do something about the issues raised.

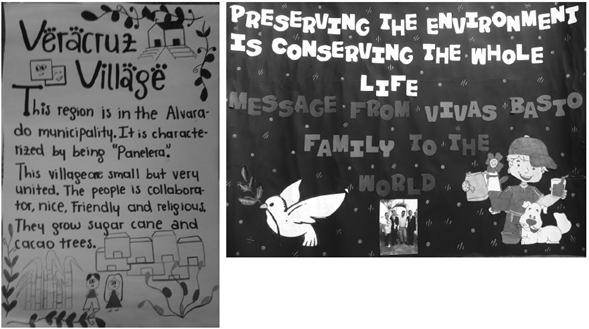

All through the process, families and the community changed their way of thinking and acting. After introducing global warming issues in class and connecting them to the fires that were damaging the villages, families designed a poster in English inviting members of the village to help take care of the environment.

Take care of our water resources by saying no to the mining industry and hydroelectric plants, less fumigations with glyphosate. More healthy lives. (Message from Family 2, Student 23)

Take care of the natural resources to avoid burning and deforestation. (Message from Family 3, Student 27)

Through these messages, families invited people to protect their primary natural resources such as water and the ecosystem to foster life, thus becoming aware of certain practices like fumigation, mining, deforestation, and the impact hydroelectric plants had on the land and crops. These families showed strong concerns about the land and nature, but at the same time suggested some ways to protect them. They showed growing awareness that every damaging effect to the environment around the world also altered their crop processes; produced shortages of water, depletion of resources, and pollution; and affected their way of life.

Subsequently, during the inquiry, their own agency became a path for this community. Families and learners started to reshape environmental practices, as is evidenced in the following excerpts from the Focus Group:

I see in my village...I have seen improvements because they see that the teacher gave us some commands it’s due to maybe she sees something wrong…when I go there, I don’t see the same…they have done it and applied it. (Student 2)

In our village we felt proud, despite there were fires, after we did in the villages people stopped burning and started to recycle, there aren’t much trash in the roads. (Student 5)

The perception of change is seen by the students in their families and communities, when a student described that she had noticed an improvement in her town, with the expression, “when I go there, I don’t see the same...they have done it and applied it” which reflects actions that transformed certain habits. Likewise, another student expressed how proudly their people had stopped practices like burning and littering. Families’ actions moved from promoting changes or making decisions to taking real actions in favor of the environment. Some students demonstrated their concerns about how taking care of the land helps to preserve their surroundings. Moreover, learners’ awareness was not just for helping a community member but also for contributing to environmental issues and changes as this statement makes clear: “After all, we do not help just one person, we also help to take care of others by helping the environment” (Student 3, Focus Group). Another participant declared how agency was converted into action: “We could grow trees, we shared food, we took care of the countryside, we recycled, we picked up garbage there, and we brought it back to put it in the right place” (Student 6, Focus Group). This quote represents the recognition of action when students began to apply the knowledge learnt in the classroom. The way they carried garbage from the farm they were visiting and the responsibility of bringing it back and putting it in the right places, showed a change in thinking, and in students’ own sense of agency. Students learned to name and identify bad practices affecting the rivers and fields, like the improper disposal of cigarettes, and recounted how people stopped those negative actions to transform their village into a better place.

Students’ experiences also began to favor not only the environment but also other members of the community. The following subcategory pictures how CBP motivated students to action in order to help one of their classmate’s family who had suffered serious damage caused by the seasonal fires.

Helping Community Members

Students began to adopt community issues as theirs, taking action to meet the needs of the people, empathizing with their feelings and thereby strengthening their personal values. This understanding emerged during the classes when environmental issues around the world and country were being discussed. Participants started making connections about how their people were also victims of climate change, for example by witnessing how forest fires were affecting the region. The following excerpts from some students’ artifacts reflect what learners understood from the visit to one of the farms in the region which was affected by the fires: “I learned it is very good to help people who need it, no matter where they come from or who they are” (Student 2, Poster); “I learned I should help my community and the people around me” (Student 14, Poster).

It seems that students were profoundly concerned, since they used expressions like “it is very good to help no matter who they are,” and “I learned I should help my community.” Students began to observe others’ needs and decided to help, moving from feelings of sorrow to acts of solidarity. When one of their classmates told them how a fire had burned their avocado plantation, they decided to devise strategies to provide support and proposed a visit to the farm in order to help clean the field and plant new trees. This was one of the students’ most significant activities of the project. They experienced feelings of happiness because they were able to help others who were in need in their home villages: “In my case I felt happy to help someone, I feel proud because we could help, I was able to do something by helping, I helped someone who needed it” (Student 5, Focus Group). These excerpts also show the profound impact that helping someone from the community had on the students’ lives. Agency was enacted by observing the community, identifying needs and situations, and taking actions to contribute meaningfully. The following excerpts, from the Focus Group, provide more illustrations about the deep feelings of happiness and enjoyment students experienced when helping a member of their community.

That’s true...we helped someone and he was happy because if we wouldn’t have helped him, he would have to pay someone else, instead we helped him with love. . . We saw the farmer very happy…we motivated him. (Student 2)

After the students had helped the farmer, they discussed the visit and how the results of helping someone was full of a sense of gratification: First, it was an opportunity to express empathy with a member of the community who had lost their crops because of fire. Second, students observed the gratefulness of the farmer and perceived his positive reactions. They concluded it was worth the time and effort and they were pleased about the job they had done. Likewise, the teacher reiterated these feelings in the journal:

One of the things that caught my attention was the love, thankfulness, and emotion students did the collage after the visit to the farmer . . . the visit to this farm helped learners to comprehend more deeply the importance of helping someone from the community . . . today we are helping the farmer and tomorrow it could be anyone of us, like today for you, tomorrow for me.

To sum up from the data analyzed above, we would argue that classrooms should be scenarios in which agency can be enacted through critical pedagogy. This decision requires teachers to open the doors to the exploration of students’ communities in order to establish meaningful connections between language and students’ needs and realities. We believe that teachers can enact students’ agency by using their communities and their contexts as curricular sources in order to give meaning to language teaching, leading students to see themselves and others by analyzing situations or events they identify with. By doing so, students envisage themselves as members of a local community, acknowledge all the richness of their surroundings and the values they have as individuals. This may move them to see others, to see the conditions of the places where they live and respond by being informed about causes and effects and making decisions to improve their surroundings. In other words, enacting agency and engaging in actions that could contribute to the improvement of their setting. In this respect, individuals are a very important asset that communities can benefit from. When teachers connect agency and CBP, classrooms become places in which students’ identity, contexts, families, and neighbors become visible, and their conditions become reasons for class discussions and reflections that result in achievable actions.

Discussion

The discussion chapter of this paper interprets the results of the study described earlier. It discusses the three subcategories: Understanding Who They Are as Farmers and Acting Accordingly, Moving Forward in Environmental Care, and Helping Community Members. Regarding the first subcategory, data revealed that through the exploration, students resignified their identity; when they saw themselves, in this case as farmers, and were able to make visible the richness and possibilities of their communities, they were moved to reflection and decision making. Problems in their communities were understood as possibilities for change and improvement; in other words, agency was enacted. In this sense, it is worth recalling Duff’s (2012) definition of agency explained above, as people’s ability to make choices in order to achieve personal or social transformation. Students were able to take control of their practices and acted according to their appreciation for their lands. The preceding outcomes bring into focus the possibilities favored by agency for giving students a voice, a non-conventional voice (Kramsch & Lam, 1999) that is connected to personal purposes and that is not governed by subordination and powerlessness regarding the cultures of the target language. Rather, it offers “the opportunity for personal meanings, pleasure and power . . . Learners . . . construct their personal meanings at the boundaries between the native speaker’s meanings and their own everyday life” (Kramsch, 1993, p. 238).

Agency is seen as a result of the exploration of the students’ identity and language learning. Norton and Toohey (2011) define the concept of identity under a poststructuralist approach, which seeks to explore links between identity and learning a foreign language. They state that when students are provided with opportunities to explore their communities’ issues, this serves as a catalyst for positioning themselves in imaginary communities where those problems could change, but instead of imagining them, they act in response to those issues in the communities and become aware of them. The perspectives on students’ identity and communities described above demonstrate the multifaceted and multidimensional ways in which learners can be looked at. Thus, the inclusion of local communities may enable learners to see “how things are and have been but [also] how they could have been or how else they could be” (Kramsch, 1996, p. 3). The imaginative ingredient added to language learning is a critical aspect for understanding the research undertaken here since it is acknowledged that a community’s culture is both real and imagined and is constantly mediated, interpreted, and recorded by language. Hence, as indicated by Kramsch (1996), language learning and teaching “[play] a crucial role not only in the construction of culture, but in the emergence of cultural change” (p. 3).

In like manner, the second category “Moving Forward in Environmental Care” and the third subcategory “Helping Community Members” are clear examples of how agency was enacted from the classrooms. Agency in the classroom is seen by van Lier (2010) as the way students make decisions, support others and themselves, and become conscious of the responsibility for one another’s actions. In this respect, the exploration of the communities as rich spaces and sources for learning moved students to understand themselves as individuals and as social subjects aware of their own community realities and agents of change that can contribute to the welfare of the members of their community. This outcome underlines the variety of ways in which students can access new knowledge through joint problem spaces, inside and beyond the classroom, to reflect and construct meaning with their peers.

To sum up, the findings of this inquiry made the following evident: first, the possibility to make choices about environmental issues affecting the community; second, raising awareness about the effects of bad environmental practices on students’ communities’ rivers and land. Students’ families and other members of the community were challenged to evaluate their practices and make decisions that ended up involving concrete actions. Third, exploring the community let students see their conditions and be moved to carry out concrete actions to benefit people in need, which evoked values such as empathy, solidarity, and partnership.

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to examine students’ agency while participating in the local community inquiry. Throughout the exploration, agency was enacted in the classroom as a process of self-awareness and decision-making. Students inquired about their community and were able to see issues that triggered not just the desire to promote changes but act in response to them. In this sense, students’ agency was revealed in their actions that not only empowered their neighbors and surroundings but spread changes that would contribute to the welfare of the area as a whole.

Among other aspects, this study provides a valuable understanding of how language teaching and learning can be enriched in rural areas and how agency can be a result of exploring CBP. Usually, education in rural areas is associated with stigmas related to the lack of resources for teaching and the idea that students are not capable of taking on academic challenges, especially when it comes to learning other languages (Llambí-Insua & Pérez-Correa, 2007). Despite lacking resources for language learning, the participants of this study demonstrated they were able to use English to report and to communicate ideas related to their communities, practices, and problems (see Appendix B which illustrates students’ writing). English was the means of instruction and discussion whereby students had plenty of opportunities to communicate their ideas. Language in this setting was more than an object of the study, it became a medium to read, understand, and react to their reality. In this sense, rural students saw English as part of their lives and made more sense of language learning.

In conclusion, when the classroom connects with students’ realities, offers spaces for authentic reflection, and is closely related to their interests and daily life, the barriers of economics and distance fall away and learning increases in response to the interaction of new knowledge with the life, space, and people that are related to the students. These connections allowed students to learn about valuable resources that caused them not only to see themselves as farmers, but also their people and surroundings. They took actions that contributed to the welfare of the place where they lived, demonstrating commitment with this type of projects.