Introduction

A seminal article published by Ball and Cohen in 1999 began a shift in conceptions of teacher education toward greater incorporation of practice in the university classroom. They argued that teacher preparation must shift from predominating models in which educators describe the techniques and methodology of teaching, to a model that more effectively incorporates the practice of those techniques and methods. A primary motivation of this argument was to counter the tendency of teacher educators to teach in the ways in which they themselves were taught (Donato & Davin, 2018; Lortie, 1975). Instead, they contended that “much of what [teachers] would have to learn must be learned in and from practice rather than in preparing to practice” (Ball & Cohen, 1999, p. 10). Since this call, a developing line of research has focused on identifying a set of high leverage teaching practices (HLTPs) required by teachers, as well as the formulation of a practice-based learning cycle through which student teachers can rehearse such practices.

In this article, we report a collaborative self-study (Troyan & Peercy, 2018) that examined our own experiences and challenges in implementing a practice-based approach in our respective foreign language teacher preparation programs. When we first met in 2018, we each had begun to actively incorporate practice-based approaches as teacher educators. We soon realized that-despite the large physical distance between us (with Malba in Chile and Kristin in the United States) and the many contextual differences-we shared many experiences and challenges in the implementation of this approach. In this article, we present the stages of the learning cycle that transcended localized contexts to support teacher educators considering the implementation of a practice-based approach in foreign language teacher education. Through analysis of our own conversations and email exchanges, we discuss related recommendations for teacher education practice and areas of caution for each of the four major phases in the practice-based learning cycle. We draw on examples from both contexts to illustrate these recommendations and cautions and analyze data from one focus student as she moved through the four phases to illustrate how candidates might learn through this process.

Literature Review

HLTPs are teaching practices in which, “the proficient enactment by a teacher is likely to lead to comparatively large advances in student learning” (Hlas & Hlas, 2012, p. s78). To be considered an HLTP, “a practice must improve the achievement of all students, occur frequently in instruction, and be learnable by novice teachers” (Davin & Troyan, 2015, p. 125). Within a practice-based approach, instruction focuses on a limited number of HLTPs which are made accessible to preservice teachers, are revisited periodically, and can be practiced (Ball et al., 2009).

Researchers within the field of foreign and second language education have begun the work of identifying their own set of HLTPs. Troyan et al. (2013) began this work, discussing their implementation of a practice-based approach around three HLTPs: (1) using the target language comprehensively during instruction, (2) questioning for building and assessing student understanding, and (3) teaching grammar inductively in meaningful contexts and co-constructing understandings. Glisan and Donato (2017, p. 28) revised and built upon those practices, identifying six practices:

facilitating target language comprehensibility

building a classroom discourse community

guiding learners to interpret and discuss authentic texts

focusing on form in a dialogic context through PACE (Presentation, Attention, Co-construction, Extension)

focusing on cultural products, practices, and perspectives in a dialogic context

providing oral corrective feedback to improve learner performance

Many teacher-preparation programs internationally-including the two programs at the center of this research-have adopted their resulting orientation.

To facilitate student teachers’ development of these HLTPs, a practice-based approach is often characterized by a four-phase cycle. The first phase is demonstration and deconstruction, in which the teacher educator shows student teachers a representation of the practice in context, such as a lesson video or transcript of a class. In this phase, student teachers and the teacher educator discuss how the components of the HLTP are portrayed in the representation. For example, they might discuss instances in the video in which the teacher used visuals and gestures to support students’ understanding of the target language, which represents a key component of facilitating target language comprehensibility. The second phase is centered on planning. In this phase, student teachers typically plan a learning segment that highlights the HLTP. Ideally, the teacher educator provides student teachers with an instructional activity in which to situate the practice. For example, Glisan and Donato (2017) recommend that student teachers practice facilitating target language comprehensibility within the context of introducing six new thematically-related vocabulary words within a meaningful context, such as introducing a story or text. After planning a lesson segment, student teachers then come together for the third phase, rehearsal and coaching. In this phase, student teachers rehearse a portion of their lesson segment, either in small groups or as a whole class if time allows, with the teacher educator acting as a guiding coach. Coaching includes discursive moves such as giving directive feedback, highlighting moves made by the student teacher, inviting discussion, and playing the role of the student (TeachingWorks, 2018). After phase three, student teachers revise their plan and progress to the fourth phase, implementation and reflection. In this phase, student teachers video-record the enactment of their lesson segment in a more authentic context, typically a classroom field site. To prompt reflection, student teachers may, for instance, watch the video and deconstruct their own practice to identify ways in which they demonstrated (or should have demonstrated) the various components of the HLTP.

Method

Context and Participants

Although we both followed this four-phase practice-based learning cycle, we each worked in distinct contexts: Malba in an initial English language teacher education program in Chile and Kristin in an initial foreign language teacher education program in the United States. In the Chilean context, the student teachers at the center of this research (n = 20) were undertaking their second teaching practice experience-in tandem with a Methods course-and were in the seventh semester of their learning program. These student teachers were engaged in a nine-semester undergraduate program, with curriculum organized into theoretical courses (in the fields of English, applied linguistics, and education), four didactics courses, and three school-based teaching practice experiences. At schools, they undertook activities such as monitoring students’ work, preparing learning materials, and teaching six classroom lessons. They worked in pairs throughout the semester, a structure which provided a consistent framework for the development of their work in both the Methods course and practicum.

In the U.S. context, student teachers (n = 5) in this research were graduate students seeking their initial teacher licensure in a 16-credit graduate certificate program. Given the escalating demand for teachers in the United States, student teachers were practicing full-time teachers, despite being unlicensed. However, it was a requirement of their employment that they were concurrently enrolled in the graduate certificate program to earn that license. The practice-based learning cycle described in this article took place during their second of three semesters, when student teachers were enrolled in a three-credit foreign language methods course, a two-credit foreign language assessment course, and a one-credit lab. All courses were online, with the exception of the lab which was a hybrid format that included three three-hour face-to-face meetings during the semester. Student teachers engaged in the activities described in this article in the lab. All four phases of the practice-based learning cycle were embedded in online modules, with the exception of Phase III: Rehearsal and Coaching, which took place in the face-to-face meetings.

Our two contexts shared important similarities and critical differences. What was similar across the contexts was the implementation of the four-phased practice-based cycle and a focus on three of the HLTPs described by Glisan and Donato (2017). Coincidentally, we had chosen two of the same HLTPs, facilitating target language comprehensibility and designing and conducting oral interpersonal communication tasks. Critical contextual differences included the sociocultural context (Chile vs. the United States), target language employed (English vs. Spanish and Chinese), student level (preservice undergraduate students vs. in-service graduate students), and delivery method (face-to-face vs. a hybrid format).

Data Collection and Analysis

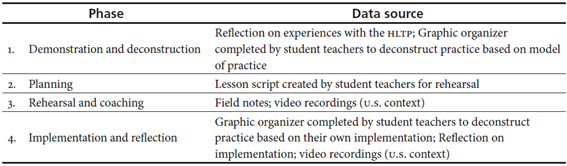

Data were drawn from pedagogical tools (i.e., assignments, rubrics, teaching materials), student teachers’ reflections and scripts, videos of rehearsal and implementation (only in the U.S. context), and our own oral and written communication. Because we were each using Glisan and Donato (2017) as a text, our approaches were similar and we had many of the same data sources (see Table 1).

Beyond student teacher data, our email communications and meeting notes served as data sources.

Data analysis occurred in two phases. For the first phase, we examined data first individually, and developed themes related to recommendations and challenges of the practice-based approach. We then met for a week for collaborative analysis and to compare themes. Our comparative analysis suggested potential productive actions and specific cautions that transcended each context, which we developed further with illustrative data from both settings. Thus, we categorized the findings into recommendations and cautions. For the second phase, we chose one focus student for whom we could track progress through the four-phased cycle. We selected Lucia (a pseudonym) from the U.S. context because we had video recordings of her rehearsal and implementation and because she was studying to be a Spanish teacher, which eliminated the need for translation. Lucia was an elementary school Spanish teacher in her first year of teaching. We analyzed the four data sources displayed in Table 1 for Lucia to track her learning through the practice-based cycle.

Findings

Phase I: Demonstration and Deconstruction

Recommendation 1. The first phase of the practice-based learning cycle consists of demonstrating and deconstructing the HLTP into instructional moves (Lampert et al., 2013). In this phase, after student teachers have read about the theoretical underpinnings and research base of the practice, the teacher educator guides students to deconstruct their practice and provide a representation of how the practice is enacted (Ghousseini & Sleep, 2011). When using video representations, it is critical that the teacher educator selects a video that clearly demonstrates the HLTP, so that the teaching moves are easily recognizable. For example, when the first HLTP (facilitating target language comprehensibility) was introduced in the Chilean program, student teachers viewed a 15-minute segment in which a former student teacher was starting a lesson on daily routine. The teacher taught in the target language and enacted most of the teaching moves suggested by Glisan and Donato (2017) for that practice, including using gestures, visuals, comprehension-checking questions and providing students with language support so that they could interact using the target language. The lesson demonstrated in the video was familiar for student teachers because it was about a topic which was mandatory in the Chilean national curriculum. The teacher educator facilitated an open discussion, using a checklist adapted from a pedagogical tool designed by Glisan and Donato, to allow student teachers to make sense of this HLTP and exchange their views on affordances and constraints of implementing this practice in their own school contexts.

Recommendation 2. An alternative to video representations of an HLTP is modelling, in which the teacher educator or other experienced teacher enacts a lesson as if they were in the field site, and as if student teachers were the intended students. Modelling should be done in a highly structured way so that student teachers are instructed to use tools (e.g., checklists, rubrics, questions) to help them identify and understand the teaching moves enacted in the modelled practice. For example, in the case of the second HLTP used in the Chilean context, focus on form, the teacher educator prepared a 15-minute lesson following the PACE model (Donato & Adair-Hauck, 2016) about giving recommendations using the subjunctive form. Instead of talking about the HLTP, the teacher educator taught this lesson as if this were an English class for intermediate students. Following the demonstration, student teachers identified examples of the various components of focus on form using a checklist (adapted from Glisan & Donato, 2017). They then discussed the affordances and constraints of the implementation of this practice in the student teachers’ own school contexts.

A Caution. The demonstration and deconstruction phase required a significant amount of time to analyze the practice and decompose it into teaching moves. However, this does not mean that theory should be abandoned or disregarded in this phase. On the contrary, student teachers should reflect on the HLTP using sound theoretical support. In this sense, beliefs about target language use and teaching and learning a foreign language in class should be explicitly considered during class discussions. Student teachers should also be encouraged to reflect on their own experiences as language learners to connect these experiences with their beliefs and research (Donato & Davin, 2018). For example, in both contexts, student teachers were asked to respond to a range of questions about their own learning experiences, such as: “Consider a positive experience of foreign language learning. What did the teacher do? What did students do? What did the teacher do to encourage students to use the target language?” Subsequently, student teachers had to critically examine their reflections and the HLTP in light of its theoretical assumptions. In this sense, this first phase acted to mediate student teachers’ understanding of theory through the deconstruction of practice (Peercy & Troyan, 2017).

The recommendations of using different representations of practice, such as videos, modelling, or analysis of scripts as part of the demonstration and deconstruction phase should be followed with caution and should be situated in the context of teaching. Although we both followed this learning cycle, each of us adapted tools and selected representations of practice according to our respective contexts including teachers’ characteristics and contexts for teaching (Danielson et al., 2018).

Lucia’s Experience

In Phase I, Lucia reflected on her past experiences with facilitating target language comprehensibility and completed a graphic organizer deconstructing a teacher’s use of this practice. For the reflection, when asked about her experiences with this practice, she explained that English was her second language and that she felt that she “learned more when the teacher spoke only in the target language.” She wrote:

In my first class in college (completely in English) when I was forced to understand the main ideas and the lesson’s purpose, that made me learn more. I can describe the experience as “bold” but I agree 100% with Chapter 1. We learn more when we focus on the comprehension and the teacher talks 100% in the target language.

However, when asked about her current teaching practices, she wrote that she needed “to improve in this aspect,” explaining:

I use the target language 50%, sometimes less than that because I teach little kids and when they don’t understand I lose their attention. I think I should use more visual aids and the media (cartoons, short clips, songs) in the target language in order to get their attention for a longer period of time and maximize our time using the target language.

For her graphic organizer, which is not included here due to space limitations, Lucia accurately identified the subcomponents of the practice from the video demonstration.

Phase II: Planning

Recommendation 1. The second phase of the practice-based learning cycle is the planning phase in which student teachers create a plan for the lesson segment that they will rehearse in Phase III. In this phase, teacher educators should scaffold student teachers’ planning by specifying the instructional activity in which to situate the practice. An instructional activity provides the context in which student teachers should demonstrate the HLTP (Lampert & Graziani, 2009). In our teacher education contexts, this meant specifying the type of lesson in which the practice should be embedded. For example, when preparing to practice facilitating target language comprehensibility, we asked student teachers to teach six new vocabulary words bound by a theme, within a meaningful and cultural context (Glisan & Donato, 2017, pp. 33-34). One student teacher, who was teaching rooms of the house, created a story about a person travelling to China and who was attempting to identify a desirable rental home. Defining the instructional activity for student teachers removed the burden from student teachers of selecting a context (Troyan et al., 2013). For instance, in the Chilean context, as another way to provide opportunities for practice, student teachers were encouraged to script and rehearse instructions for an interpersonal communicative task. These instructions needed to integrate a wide range of instructional moves that facilitated target language comprehensibility.

Recommendation 2. A second recommendation related to Phase II: Planning concerns the level of detail of the lesson plan that teacher educators should require. The plan that a student teacher submits for a practice-based course should be designed differently than the plan submitted for a more traditional methods course. For example, a more traditional lesson plan might include multiple portions of the lesson (i.e., focus & review, teacher input, guided practice) and provide a description of what will occur in each segment. When planning for lesson rehearsal, following the recommendations of Glisan and Donato (2017), we determined that student teachers should carefully script a 10 to 15-minute segment of the lesson that they intended to rehearse. Such scripting included both what the teacher intended to say, as well as what he or she expected the students might say. While certainly not expected to read or stay faithful to the script, thinking through the lesson segment in this way encouraged student teachers to more carefully consider discourse possibilities. Moreover, it allowed them to more systematically analyze their scripts for the components of the HLTP before submission.

A Caution. A critical component of Phase II is that it requires student teachers to submit their lesson scripts in advance, in order to allow time for the teacher educator to provide feedback and for the student teachers to revise. For example, in one case when engaged with the HLTP of designing and conducting oral interpersonal tasks, a student teacher submitted a plan for her rehearsal that suggested she had not grasped the concept of interpersonal communication. Her lesson did not require students to listen to each other, a key component of interpersonal communication (i.e., two-way spontaneous communication in the target language). Had the teacher educator not reviewed the lesson script prior to the rehearsal, this student teacher’s rehearsal would have been fruitless for both her and her classmates. Such advanced planning can be difficult because it requires student teachers to plan a lesson that will not be taught to their students for approximately two weeks. This is to permit sufficient time for the teacher educator to provide productive feedback, for the student teacher to make any necessary revisions, and for them to subsequently rehearse and revise the plan. The length of time between the rehearsal and the enactment in the K-12 setting influences not only the focus of the rehearsal (Kazemi et al., 2016), but also impacts on how much of the coaching the student teacher remembers from the rehearsal. However, the time required for the process of feedback and revision is too critical to be compromised.

Lucia’s Script

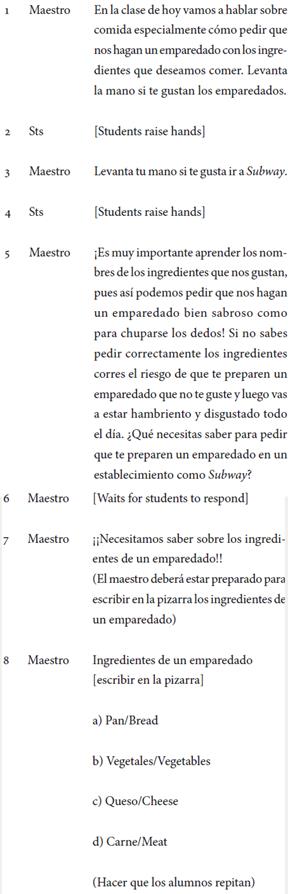

After reflecting on her own experiences and deconstructing a model of the practice, Lucia had a week to plan and script her own lesson. Her lesson focused on teaching students sandwich vocabulary and how to order in a restaurant and was part of a larger unit on food. In addition to scripting what they planned to say as well as what they expected students might say, student teachers were also asked to include teacher actions in brackets. Excerpt 1 displays the initial portion of the Teacher Input section of Lucia’s lesson.

Excerpt 1. Lucia’s Rehearsal Script for Facilitating Target Language Comprehensibility

As Excerpt 1 illustrates, Lucia planned to begin her lesson by introducing the objective for the day. Her entire script was in the target language and she had incorporated opportunities for students to respond. However, she included few brackets describing her own actions and there was no mention of visuals or gestures.

Phase III: Rehearsal and Coaching

Recommendation 1. Lesson rehearsals are approximations of practice, which form critical learning activities in a practice-based approach as they act as dialogic mediating tools for student teachers’ development (Troyan & Peercy, 2018). In this phase, student teachers enact their lesson segments with a special emphasis on the components of the HLTP and pause-or are asked to pause-their teaching to be coached by the teacher educator. A key recommendation for this phase is to maximize the opportunities for rehearsal. In our teaching contexts, each student teacher had the opportunity to enact their lessons or segments of lessons and receive coaching. However, in the U.S. setting, student teachers planned their lessons individually and rehearsed each HLTP in different rehearsal sessions. In the Chilean context, student teachers worked in pairs and planned lessons collaboratively, with one student teacher rehearsing a segment of the lesson and receiving direct coaching. Student teachers rotated to rehearse their lessons during the semester so that all were able to perform the role of the teacher and rehearse one HLTP during the semester. Another strategy that was used to enhance the opportunities for practice was having student teachers record themselves practicing segments of lessons in advance (i.e. starting the lesson, giving instructions, explaining vocabulary, conducting an interpersonal communication task). This strategy was used to scaffold the learning process and to contribute to the level of student teachers’ confidence and self-efficacy. However, it is important to note that these videos did not replace the rehearsal sessions, but worked primarily as stepping stones.

Recommendation 2: Another key recommendation in Phase III: Rehearsal and Coaching is to carefully plan coaching moves, with careful attention to context, to provide opportunities for the interrogation of teachers’ practice and its consequences. When coaching, the teacher educator guides student teachers through the enactment of teaching moves. This includes such elements as giving directive feedback, highlighting the importance of a teaching move enacted by the student teacher, asking a question for reflection, or modelling a specific move to be enacted by the student teacher (TeachingWorks, 2018).

In the Chilean context, student teachers planned minilessons (with a focus on facilitating target language comprehensibility and building a discourse community) in pairs and subsequently rehearsed their lessons in class. The teacher educator paused the lesson at critical moments of the rehearsal to coach student teachers by making suggestions such as “Use a synonym, point to the picture,” or by asking questions such as “Why did you choose to teach those words?,” or “What do you think your students would do after you said that?” The teacher educator enacted a wide range of coaching moves which required a high level of self-confidence to know when to pause the lesson and which coaching move to use. Most student teachers were open to criticism and willing to interrogate their own practices. After the rehearsal sessions, student teachers wrote their reflections on the feedback and suggestions discussed in class and how they would consider them for their future implementations in school.

A Caution. In this phase, student teachers actively engaged in preparing the rehearsal session and enacting it. The rehearsals typically focused on one HLTP or a set of instructional practices. However, it was important that a set of norms was established before the rehearsal session so that everyone understood its intended structure, as well as assigned roles and functions (Kelley-Petersen et al., 2018). For instance, in the Chilean context, the first rehearsal session was a challenge. Student teachers were not sufficiently clear as to their roles and the structure of the session. So, when the teacher educator paused the lesson, the first student teacher reacted very defensively and did not integrate the feedback into his teaching.

In addition, in the case of some specific practices such as designing and conducting oral interpersonal communication, it can be difficult to effectively rehearse all aspects of the HLTP. For the rehearsal, other student teachers need to play the role of students and be able to engage in the interpersonal task. In this sense, student teachers need to share the target language at a similar level of proficiency. In contexts in which the Methods course is taught to teachers of different foreign languages, it is recommended that instead of rehearsing all aspects of HTLP, only a set of instructional moves such as activating background knowledge and providing language support be enacted. Teachers can still gain significant learning in planning the rehearsal of the interpersonal task and its instructions.

Lucia’s Rehearsal

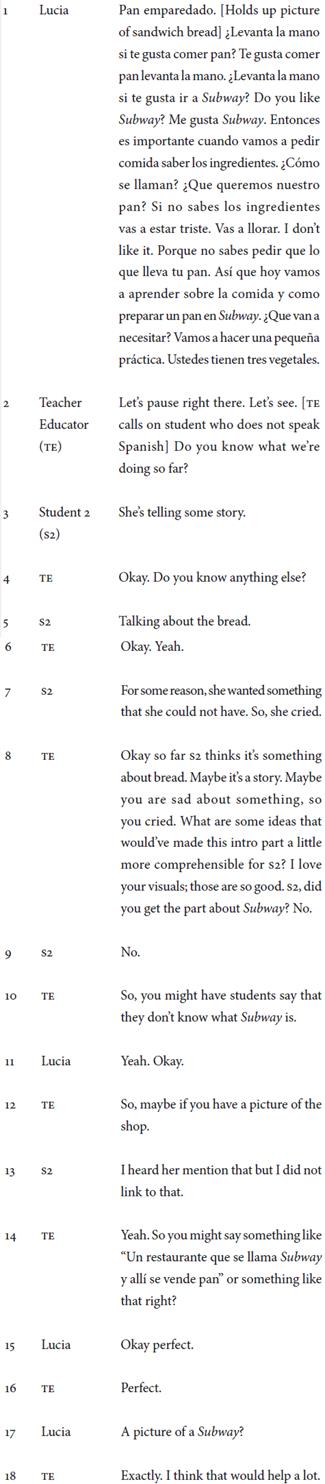

As Excerpt 2 illustrates, Lucia’s rehearsal began slightly differently than she had planned. This was to be expected, because student teachers were told that they did not have to follow the script word-for-word, but that its purpose was more to carefully think through the lesson.

Excerpt 2. Lucia Rehearsal Transcription

As Excerpt 2 illustrates, Lucia, began her lesson in Turn 1 with a series of sentences interspersed with questions in Spanish, just as she had planned to do. However, unlike her script, she translated her phrases to English twice (Turn 1), despite the requirement that she use only the target language. In Turn 2, the teacher educator interrupted Lucia and called on a Chinese student teacher in the class to inquire about whether she had understood Lucia. Turns 3, 5, and 7 revealed that she had not. As a result, the teacher educator complimented Lucia’s use of pictures (Turn 8), asked a question for reflection (Turn 8), provided directive feedback (Turn 12), and modeled a way to make her language more comprehensible (Turn 14).

Phase IV: Implementation and Reflection

Recommendation 1. One of the most critical recommendations related to Phase IV: Implementation and Reflection concerns the need for flexibility on the part of both the teacher educator and the student teacher. It is inevitable in schools that there will be unanticipated interruptions (such as an unexpected field trip or cancellation of school for a weather emergency) and student teachers will not necessarily be able to enact their lesson in the K-12 classroom on the day that they had planned. In some cases, we have had student teachers who were not able to enact the lesson that they had rehearsed at all. For example, one student teacher planned and rehearsed a lesson that illustrated the HLTP of facilitating target language comprehensibility. However, when she returned to her field site the following week, she learned that her clinical educator had already taught the content. In this case, the student teacher had to implement the HLTP in a lesson plan that she had not yet rehearsed. Strict due dates on lesson implementations and reflections can cause added stress to student teachers who are already overwhelmed with the demands of learning to teach.

Recommendation 2. As the length of many teacher education programs across the world decreases, the placement of student teachers in field sites for student teaching becomes even more critical. For example, in the U.S. context described in this study, the graduate certificate program required only 16 credits, three of which were dedicated to student teaching. As a result, the practices and beliefs of clinical educators (often referred to as cooperating teachers in the United States or profesores mentores in Chile) have a profound impact on student teachers’ development (Delaney, 2012). To develop the ability to carry out these HLTPs, student teachers must be placed in classrooms where clinical educators model these practices on a daily basis. In both of our contexts, we have had experiences where student teachers were placed in classrooms in which the clinical educator did not agree with the focused practice of facilitating target language comprehensibility and wanted our student teachers to use more of the students’ first language and did not allow student teachers to implement other instructional moves. Such placements undermine the practice-based learning cycle and put the student teacher in a stressful position that can inhibit their development as teachers.

A Caution. A critical component of Phase IV is for student teachers to video-record their enactment, which comes with its own set of inherent challenges. On the most practical level, video-recording has become much simpler with cell phones; however, student teachers must remember that most phones stop recording after 15 minutes. A more profound consideration deals with who is captured in the video. In order for students to appear in the video, student teachers must secure signed permission forms from students’ parents. As a result, our student teachers often submit teaching videos that show only themselves teaching. It is often difficult to draw conclusions about the extent to which students were engaged, how many students were participating, and what exactly they were doing. In fact, a video of only the students might be more telling than a video of only the teacher.

Lucia’s Implementation and Reflection

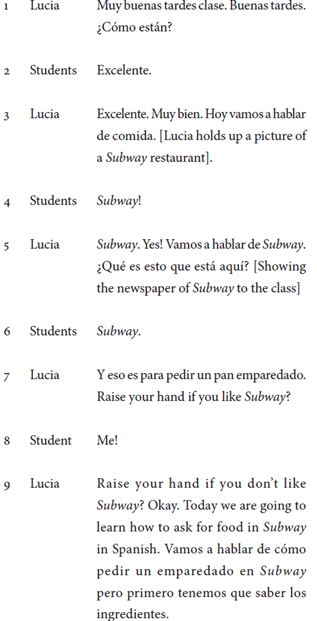

Building on Excerpts 1 and 2, Excerpt 3 illustrates Lucia’s implementation of the portion of her lesson rehearsed in Excerpt 2.

Excerpt 3. Lucia’s Classroom Implementation

Excerpt 3 illustrates how Lucia translated one instance of coaching into her lesson implementation with students. Comparison of Excerpts 2 and 3 illustrates that Lucia more effectively focused learners’ attention on the topic of the lesson by shortening her introduction and simplifying her language. While Turns 7 and 9 revealed Lucia’s continued struggles with using solely the target language, Turns 3 and 5 revealed that she implemented the teacher educator’s feedback by providing students with a visual to make her talk more comprehensible.

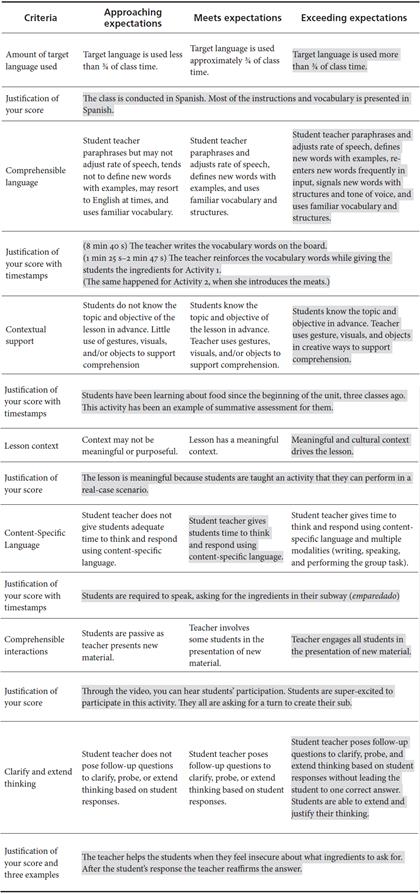

Following lesson implementation, the student teachers also self-assessed their implementation using the same deconstruction tool that was used in Phase I. Table 2 displays Lucia’s assessment of her own lesson with the highlighted elements corresponding to her perceived scores and justifications. This pedagogical tool allowed student teachers to examine their practices and find opportunities for improvement.

Discussion and Conclusion

Responding to international trends toward more practice-based approaches in language teacher education (Davin & Troyan, 2015; Pang, 2018), we both incorporated a practice-based learning cycle in which student teachers engaged in language teaching practice. Based on our individual experiences and dialogue about our contexts, supported by our reflections and the analysis of student teachers’ outcomes, we believe that incorporating this approach into the university foreign language teacher education classroom offers a useful opportunity to examine and illuminate some of the complexities of foreign language teaching practice across contexts.

As demonstrated by our two experiences, student teachers need to engage in practice, enacting key instructional moves that are suitable for a situated context. However, this enactment needs to be accompanied by constant reflection about the implementation in real classrooms and its implications for students’ learning. This reflective process allows student teachers to make connections with theoretical underpinnings more meaningful and relevant for them, offering a potent means of potentially shaping and reshaping their conceptual knowledge (Peercy & Troyan, 2017). It also appears that this consistent dialogue and personal inquiry can foster student teachers’ identity development as more reflective teachers.

Rehearsal sessions have the potential to be crucial in teachers’ development as they are,

informed not only by the knowledge for enacted practice that is the goal of the activity (i.e., unassisted implementation of the core practice), but also by the broader individual, historical, and contextual factors, including the kind of mediation provided, that construct the activity setting of learning to teach a second language. (Troyan & Peercy, 2018, p. 270)

In this sense, it is important to consider that a practice-based approach is adopted in more than one course of a teacher education program. Such iteration allows student teachers to develop a more sophisticated understanding of language teaching practice. This means not only developing an appropriate set of effective instructional moves, but also a complex understanding of what teaching and learning a foreign language implies.

Furthermore, this collaboration affirmed that teacher educators must carefully plan instructional activities within the context of the university setting, considering appropriate mediation tools and scaffolds in each phase of the practice-based learning cycle. The learning cycle implemented proved to be essentially student-centered and contributed to the construction of a continuum of practice-based teaching opportunities from university settings to school contexts. In this sense, we confirmed that instructional activities need to be aligned with the school so that they can foster student teachers’ learning in a situated context. Reflecting on the outcomes of our differing implementations of this approach, we concur with the observations of Peercy et al. (2019), who contend that:

Teacher educators must employ [practice-based teacher education] in ways that are mindful of tensions between providing sufficient support to [novice teachers], while also not ignoring context, teacher and student subjectivities and agency, and the cultural and linguistic resources that students and teachers bring to teaching and learning. (p. 9)

As language teacher educators, we have been challenged in integrating and adopting this practice-based approach as a viable pedagogy in our foreign language teaching methods courses. We have implemented this approach, taking clear account of the cultural and linguistic resources of our student teachers, through the development of responsive tools to support them in our unique settings. However, we have also reflected on our own understanding and expertise of language teaching, as well as the complexities of practice (Peercy & Troyan, 2017). Consistent with this perspective, we concur with other studies (see Grosser-Clarkson & Neel, 2019) that call for more “transparent reporting on practice and investigation of practice” (p. 11). Such transparency can provide a more developed understanding of how the practice-based approach impacts teaching and thereby contribute to the design of more effective learning responses.

Finally, we conclude that future studies should critically investigate the longitudinal effects of a practice-based approach to teacher preparation to make a more robust empirical foundation for informing language teacher education practice. This form of research could potentially allow for the development of more responsive language teacher pedagogies that more effectively contemplate the realities of changing classroom practice.