Introduction

Assessment has been widely recognized as an indispensable part of a language teacher’s job. A great deal of a teacher’s time is typically spent on undertaking various assessment and evaluation activities such as developing and administering tests, rating examinees’ performances, and making appropriate decisions regarding the test-takers’ proficiencies and the quality of teaching and learning activities (Ashraf & Zolfaghari, 2018; DeLuca & Klinger, 2010). Language assessment is not solely a means to monitor and rank students’ achievements at the end of a course and make decisions about their futures (i.e., assessment of learning). Teachers may also carry out assessment for learning in order to improve students’ learning through providing frequent informative feedback, building their confidence, and helping them undertake self-regulated learning and assessment to feel responsible for their own success (Levi & Inbar-Lourie, 2020; Stiggins, 2002). It might also be beneficial for teachers by providing them with ample evidence to regulate their instruction and to sharpen their pedagogic and evaluative qualities (Mertler, 2016). Accordingly, it is necessary for language teachers to have sufficient language assessment literacy (LAL) to maximize teaching and learning practices in classrooms through carrying out efficient assessments (DeLuca & Klinger, 2010; Harding & Kremmel, 2016).

Widely acknowledged as a significant construct (Scarino, 2013; Taylor, 2013), LAL is generally regarded as the skills, abilities, knowledge, and expertise that language assessors are required to attain in order to carry out efficient language assessments (Fulcher, 2012; Inbar-Lourie, 2017). Fulcher (2012) defines teachers’ LAL and, more specifically, the skills that they need to acquire to be assessment-literate as:

The knowledge, skills and abilities required to design, develop, maintain or evaluate, large-scale standardised and/or classroom based tests, familiarity with test processes, and awareness of principles and concepts that guide and underpin practice, including ethics and codes of practice. The ability to place knowledge, skills, processes, principles and concepts within wider historical, social, political and philosophical frameworks in order to understand why practices have arisen as they have, and to evaluate the role and impact of testing on society, institutions, and individuals. (p. 125)

In spite of the continuing controversy about what LAL is required for different stakeholders (Inbar-Lourie, 2017), there is a consensus that language teachers are the largest group of LAL users and, consequently, require LAL most immediately (Harding & Kremmel, 2016). To perform assessment activities that are consistent with the desired learning objectives, language teachers are required to obtain appropriate LAL. Lack of LAL would threaten the reliability and validity of a test considered for the evaluation of language learners and, as a result, impede students’ language learning (Xu & Brown, 2017). Therefore, promoting teachers’ LAL through, for instance, launching language assessment training programs, appears essential in developing their assessment skills. Apart from tapping into the knowledge and skills that teachers are required to acquire to be assessment-literate, language assessment training programs need to address teachers’ perceptions and personal training needs (Vogt et al., 2020).

Different facets of language assessment training have been studied in western academic settings including teachers’ training needs and the efficiency of face-to-face and virtual training (Malone, 2008; Vogt & Tsagari, 2014). However, it is still underexplored in the higher education context, particularly in parts of the world where education is exam-oriented (Yan et al., 2018). Accordingly, there is a dearth of research concerning language assessment training in the Iranian higher education context. In other words, previous studies have scantly explored the assessment training university English instructors have received or wish to receive in the Iranian context. The present study, therefore, sought to examine university-level English instructors’ assessment training experiences, classroom assessment practices, and assessment training needs (ATN) in Iran. University instructors are recurrently busy with assessment-based activities such as generating and administering tests, rating or ranking performances, providing feedback, and making decisions. Therefore, exploring university instructors’ ATNs may help them generate a more profound understanding of their assessment skills and, consequently, induce teacher educators to design and offer training programs in line with the instructors’ needs.

The present study sought to find appropriate answers to the following questions:

Literature Review

The term assessment, for many years, was associated with the process of evaluating and summing up what pupils had learned and achieved at the end of a certain course. In this traditional approach, known as summative assessment or assessment of learning, “the actions that guided learning processes before the end of the course were generally not regarded as kinds of assessment” (William, 2011, p. 4). More recently, however, there has been a growing tendency to practice formative assessment or assessment for learning with the aim of guiding and forming students’ learning based on their potential capabilities and adjusting pedagogic practices to the needs of the learners. Despite some minor distinctions between formative assessment and assessment for learning (see Swaffield, 2011), the two terms are usually used synonymously in the related literature (see Dann, 2014, for further discussion). Motivated by the assessment for learning initiative, developing LAL has become critical for language teachers and the subject of discussion and research in the related literature (see Hasselgreen, 2008; Hasselgreen et al., 2004; Reckase, 2008; Scarino, 2013; Taylor, 2009; Vogt & Tsagari, 2014; Walters, 2010).

The related literature is replete with studies which have examined LAL among English language teachers working in schools (e.g., Chung & Nam, 2018; Guerin, 2010; Hasselgreen et al., 2004; Watmani et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2018; Zulaiha et al., 2020) and institutes (e.g., Crusan et al., 2016; DeLuca & Klinger, 2010; Lam, 2015). The teachers in most studies (e.g., Crusan et al., 2016; Lam, 2015; Malone, 2017; Vogt & Tsagari, 2014; Watmani et al., 2020) were reported to demonstrate underdeveloped LAL and to lack adequate skills and knowledge to carry out a fair and efficient assessment. Watmani et al., for instance, studied LAL among 200 Iranian high school teachers of English and concluded that the teachers had poor assessment literacy competence.

The disappointing condition of language teachers’ LAL highlights the urgent need for training teachers in this regard (Fulcher, 2012; Malone, 2017). Hasselgreen et al. (2004), for example, examined this issue in the European context and came to the conclusion that insufficient attention was paid to training teachers in the field of language assessment and evaluation. Guerin (2010) also reported that the participants in his study had not received adequate assessment training and called for programs that could enable them to become more skillful assessors. Fulcher (2012) and Chung and Nam (2018) have also reported similar findings in their studies in which the participating instructors voiced the need for training programs that prepared them to be experts in designing and developing tests. On the other hand, the teachers who participated in Gan and Lam’s (2020) study did not give much weight to assessment training programs and refrained from attending such programs due to personal factors. Hence, it seems that no consensus on the criticality of assessment training programs has been reached in the related literature.

In general, the findings reported in previous related studies have suggested ATNs as highly contextualized and individualized factors. Language instructors from various settings with specific educational norms have reported different training needs. Tsagari and Vogt (2017), for example, scrutinized language teachers’ ATNs across seven European countries and found that the instructors from different countries focused on varying priorities in their assessment training programs and whether they showed desires to attend training programs depended on the assessment culture of their country. Greek teachers, for instance, required advanced training courses since the English curriculum standards as well as the Ministry of Education in the country emphasized the significance of assessment practices in academia. In contrast, German teachers exhibited moderate training desires concerning skill-based assessment because German foreign language learners were evaluated by national tests mainly based on linguistic skills.

Due to the context-specific nature of LAL, ATNs are often customized. Specifically, since teachers’ LAL involves their knowledge, abilities, attitudes, and beliefs about assessment (Scarino, 2013), their ATNs can differ individually. The English language teachers participating in various studies (e.g., DeLuca & Klinger, 2010; Yan et al., 2018) voiced greater training needs for assessment practice than for assessment theory. They, specifically, did not show any interest in theoretical principles of language assessment and refrained from applying the theories in their assessment practices. ATNs are also individualized owing to some contributing factors. Yan et al. (2018) argued in this regard that an enormous workload prevents language teachers from expressing their ATNs in assessment theories and principles because it is challenging and time-consuming to study and acquire these theories and principles. Teachers’ varying individual desires may also be due to the imbalanced training contents that they have received (Lam, 2015). Lam (2015) also argued that language assessment courses fail to provide preservice teachers with the essential assessment skills. This inefficiency, in his view, results in the generation of different assessment skills and, consequently, various ATNs.

Although the previous studies have yielded precious insights into assessment training for language teachers, they have mainly been concerned with English teachers working in schools or institutes and only a few were on university instructors. Likewise, as the review of the related literature indicates, university English instructors’ ATNs are underexplored in the Iranian context. The current study, therefore, was carried out to fill this gap.

Method

A mixed-method design was used in the present study. More specifically, in order to complement and triangulate the collected data to provide a more profound understanding of Iranian university English instructors’ ATNs, both quantitative and qualitative data were accumulated and analyzed. Online questionnaires and semi-structured interviews were employed to collect quantitative and qualitative data respectively.

Participants

The study was conducted after the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, which gave the researcher no choice but to find appropriate cases through social networks. More specifically, to sample the participating university instructors, the researcher randomly looked for appropriate cases in some academic social networks such as LinkedIn and Academia and sent them messages containing a brief description of the objectives of study along with formal participation requests and the questionnaire. They were also requested to share their demographic information and leave their telephone number or email address at the end of the questionnaire if they were interested in receiving the follow-up interview. The messages were sent to more than 300 English instructors who taught at the university level in Iranian state, Azad, Payame-Nour, and applied science and technology universities.

Eventually, 68 instructors (28 men and 40 women) with the age range of 30 to 58 years participated in the study by filling in the questionnaires. Fifty-nine participants taught English to non-English major students and nine taught English major students. The majority of the participants (about 80%) got a master’s degree in applied linguistics, linguistics, English literature, or English language translation. The rest had a doctoral degree in the mentioned fields of studies. Their teaching experiences ranged from 3 to 21 years.

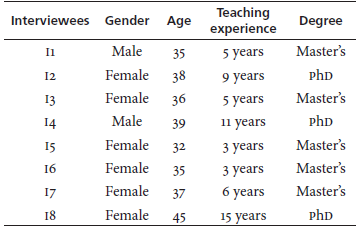

Fourteen participants agreed to receive follow-up interviews. The researcher, subsequently, selected one volunteer randomly and interviewed him through Skype. After analyzing the recorded data, he interviewed another case through the same procedure and kept it up to reaching the status of data saturation and coherence. The recorded data saturated after the participation of eight participants whose demographic information is shown in Table 1.

Data Collection Instruments

To accumulate the quantitative data, the questionnaire developed by Vogt and Tsagari (2014) was adapted and used. This instrument was selected since it has also been employed and validated in similar studies on ATNs such as Lan and Fan (2019). It consists of three sections. The first section seeks participants’ demographic information including their gender, age, academic degree, teaching experience, student types (English or non-English major), and educational background. The second section investigates the assessment training respondents have received and wish to get. This section comprises three thematic areas including concepts and content of language testing, aims of testing and assessment, and classroom assessment performances. Each thematic area is divided into two parts: received training and needed training. A three-point Likert scale is used for each item with not at all, a little, and advanced options for received training and none, basic, and advanced for needed training. It is worth mentioning that the terms a little, basic, and advanced are quantified to dispel any likely ambiguity. More specifically, the terms a little, basic, and advanced are specified as training for one day, two days, and three or more days respectively. At the end of the questionnaire, one open-ended question is used to seek instructors’ perceptions about their specific ATNs.

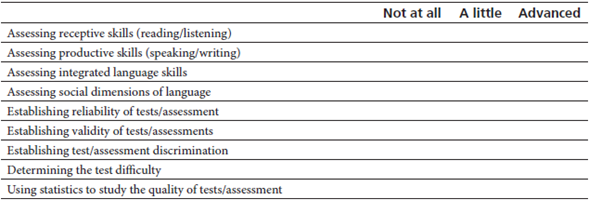

The questionnaire was piloted with four English instructors teaching in Iranian universities. As a result of the comments provided by the respondents, some minor changes were made to the questionnaire including removing similar items, rewording the technical terms, and reordering the items. Eventually, the questionnaire (see Appendix A) comprised 22 items including nine items for concepts and content of language testing, four items for aims of testing and assessment, and nine items for classroom assessment performances.

Semi-structured interviews were also used to triangulate the collected data and let the respondents extend, elaborate on, and provide details about their perceptions of their ATNs. Such a plan could lead to the richness and depth of the responses given by the respondents as well as the comprehensiveness of the emerging findings. The interview questions were concerned with the respondents’ classroom assessment practices, assessment training experiences, assessment learning resources, and ATNs. The interview questions (see Appendix B) were developed in English and, subsequently, checked by two experts who were teaching English-major students in Iranian universities.

Data Collection Procedure

Since the study was conducted after the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 and also focused on a wide range of university teachers from various universities in the country, the researcher sought to take the advantage of academic social networks (e.g., LinkedIn and Academia) to collect the data. More specifically, the researcher found cases with the required features on social networks and sent them the intended message and the questionnaire. Seventy-one respondents returned the questionnaires after about three months. Three submissions were excluded due to incomplete responses. The responses given in the rest (68 questionnaires) were loaded into SPSS 24 to be analyzed.

After collecting the quantitative data, the researcher strived to contact the respondents who left their telephone number or email address at the end of the questionnaire and set an interview time with the volunteers. The interviews were conducted and recorded through Skype. To facilitate the communication and give the respondents the chance to elaborate on their viewpoints at length, they were privileged to opt for the language to respond freely. To ensure the trustworthiness of the data, the researcher sought to avoid bias through the recommended strategies (for more details see McMillan & Schumacher, 2006). More specifically, he persistently employed field work, accounted for participants’ language verbatim accounts, and checked the data informally with the participants during the interviews. In addition to recording all interviews with the permission of the participants, the researcher took hand-written notes of the key points of the interviewees’ responses throughout the interviews.

Data Analysis Procedure

SPSS 24 was employed to analyze the data collected through the questionnaires. Analysis of the data indicated a strong internal and consistent reliability of the questionnaire (α = 0.92). Descriptive statistics of the 23 items, including their frequencies and percentages, were reported to answer the research questions quantitatively. Besides, the frequency of the recurring themes was calculated to analyze the responses given to the open-ended question.

The recorded interviews were analyzed inductively and deductively. To conduct the inductive procedure, the interview contents were analyzed through code-labeling and identifying recurring themes. That is, the data from both interviews and open-ended questions were transcribed verbatim and integrated with the notes taken. The transcriptions were then read frequently and recursively so that the interactions could be envisaged in detail. This also helped to find connections between the results emerging from both sources. The researcher developed open codes concerning the research questions independently, which sometimes entailed going back and forth through the data. The categories and relationships among the themes emerged from more refined cross-referencing among the themes, memos, and participants’ accounts. This procedure proceeded incrementally up to data saturation and coherence and, eventually, conclusions. The deductive approach taken in the data analysis procedure involved referring to questionnaire items as categories. To ensure coding reliability, coding and thematizing were verified by an expert who was an associate professor of applied linguistics and had a great wealth of research experience.

Results From Questionnaires

The results are discussed in the three thematic areas considered in the questionnaire including concepts and content of language testing, aims of testing and assessment, and classroom assessment performances.

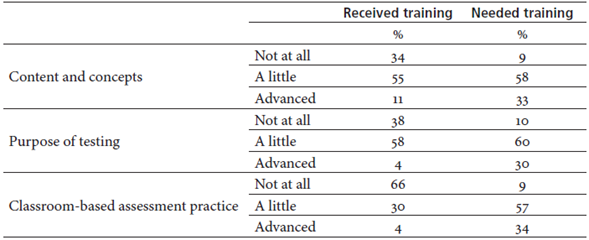

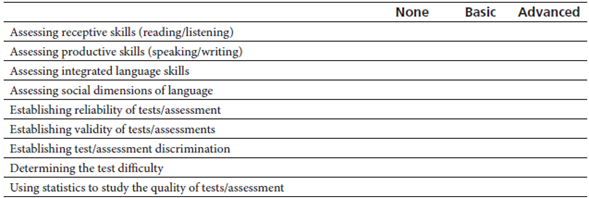

Content and Concepts of Language Testing

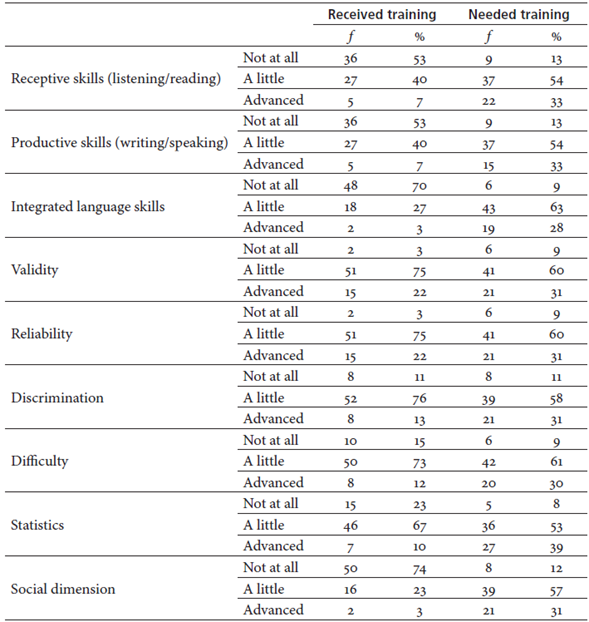

As can be seen in Table 2, it seems that most of the training the respondents received in the content and concepts revolved around the qualities of a test. That is, less than 11% of the respondents claimed that they had received no training in the concept and content of test reliability, validity, and discrimination. Only two respondents reported no training in the concept and content of test reliability and validity. On the other hand, more than half of the participants did not receive any remarkable training in the content and concept of assessing language skills and the social dimension of language assessment. Social dimension, among all content and concept areas, appears to be the most neglected one in training, with 74% of respondents reporting no training in this regard. Integrated language skills were reported to be the second least trained area of content and concepts among the respondents, 70% of whom claimed no training at all.

Table 2 Respondents’ Assessment Training Received and Needed in Content and Concepts

Note. The percentages have been rounded up and down.

Concerning the respondents’ ATNs, Table 2 indicates that the majority of the respondents longed to receive training in all concept and content areas of language assessment. However, their needs for basic training were unveiled to be stronger than those for advanced training. That is, more than half of the respondents reported a need for basic training in all content and concept areas, whereas about one-third of them desired advanced training in content and concepts.

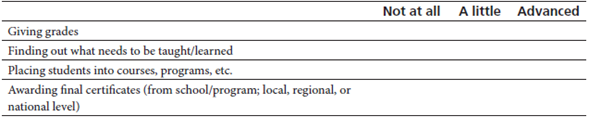

Aims of Testing and Assessment

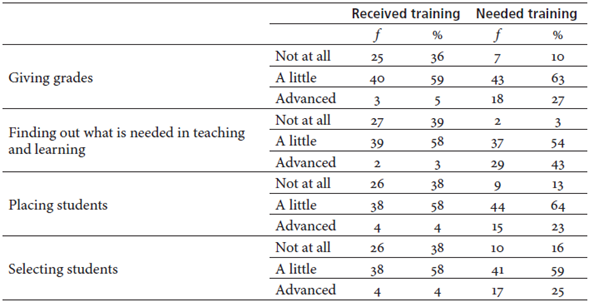

The results in Table 3 show that more than one-third of the participants had not received any training in the four areas concerned with the purposes of testing and assessment. One out of two respondents claimed that they had received basic training in the four issues dealing with the purpose of testing. It was also revealed that the amount of advanced training that they had received in any of the four areas was negligible. That is, only less than 5% of the respondents reported receiving advanced training in the purpose of testing and assessment.

Table 3 Respondents’ Assessment Training Received and Needed in Purpose of Testing

Note. The percentages have been rounded up and down.

Most of the participants also thought they still lacked training in the four areas covered in this theme. However, they showed greater tendencies to attend basic training sessions about the purposes of testing and assessment rather than advanced ones. The participants seeking to receive training in “finding out what is needed in teaching and learning” made up the largest percentage of advanced training applicants at 43 percent. It may indicate the respondents’ attention to the significant connection between assessment and teaching.

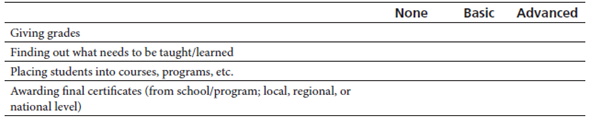

Classroom-Based Assessment Performances

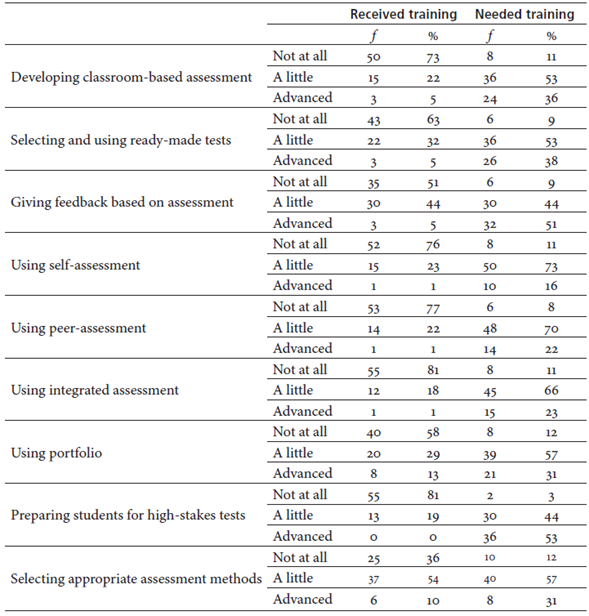

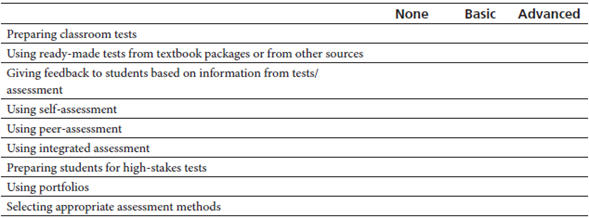

The results in Table 4 indicate that more than half of the respondents received no training in the practical aspects of classroom assessment except for “selecting appropriate assessment methods,” with less than two-thirds of the respondents receiving training. Among these classroom-based assessment practices, “preparing students for high-stakes tests” and “using integrated assessment” seem to be the most neglected areas in training, with more than four-fifths of respondents reporting no training in these aspects. Less than 8% of the respondents reported attending advanced training sessions in any of the classroom-based assessment practices. On the other hand, nearly 90% of the respondents expressed their desire to attend either basic or advanced training sessions in the practical aspects. Except for “preparing students for high stakes exams,” the instructors expressed more need for basic training in classroom-based assessment practices.

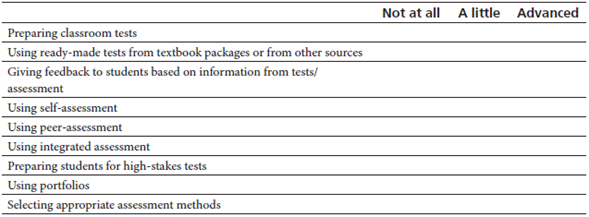

Overall Results

As indicated in Table 5, the majority of the instructors (66%) had not received any training in the practical aspects of classroom assessment, which also turned out to be the most neglected area among the examined assessment themes. The proportion of the instructors receiving no training in the other two thematic areas was similar (i.e., about one-third). Besides, most of the training that the respondents had received was reported to be basic.

The results also show that the respondents demonstrated similar ATNs in the three thematic areas. That is, nearly 60% and 30% of the instructors reported their desire to get basic and advanced training respectively in any of the examined areas. Also, about 10% of the respondents had no interest in receiving training in any of the three thematic areas.

Findings From the Interviews and the Open-Ended Question

The interviews were carried out to reveal the respondents’ assessment training experiences, classroom assessment practices, and ATNs. The latter was also scrutinized by the open-ended question used at the end of the questionnaire.

Training Experiences and Classroom Practices

Iranian preservice instructors are typically exposed to various assessment and testing concepts, principles, and approaches in formal higher-education courses for the first time (I1, I2, & I6). Some common testing and assessment concepts -including reliability, validity, practicality, rating, and assessment purposes- were learned from those courses (I1, I2, I5, & I6). However, as four of the respondents argued, they have failed to apply the knowledge and skills they learned in actual classes since they became in-service instructors. Also, no training plan has been considered by universities to help in-service instructors to extend and enact their prior assessment knowledge (I2, I4). This is vividly presented in I2’s words:

I have to admit the fact that I have learned nothing about language testing except some broad theories, definitions, and principles that were presented in my university courses. Honestly, what happened to me regarding language testing was just superficial learning. I just memorized the most important definitions and notes to pass my testing exams. And, honestly, I do not remember much about my testing lessons because I have never tried to use those theories in my classroom assessment practices. Also, my university has never required us or has never considered a program to train us to employ our testing knowledge in practice.

The interviewees were also asked to elaborate on the strategies they had used to compensate for the lack of assessment training. Seven out of the eight respondents maintained that they had done nothing to promote their classroom assessment abilities after graduation and had never been exposed to any language testing resources because language testing had never been their academic area of interest. Two instructors (I2 & I7) also attributed this negligence to their universities, which did not attach much weight to “recent and up-to-date testing methods” (I7) and required their instructors to “stick to old-fashioned methods” (I7). I3 was the only instructor who had compensated for his lack of assessment training through “reading assessment books and recently-published papers.”

Assessment Training Needs

Nearly 90% of the participants who answered the open-ended question aired their needs for training in various assessment areas. They were eager to receive training in practical aspects of testing (n = 42) and, more specifically, learn to develop a standard test (n = 16), implement formative assessment in their classes (n = 12), interpret test scores efficiently (n = 8), and prepare candidates for high-stakes exams (n = 5).

Along the same lines, all interviewees unanimously voiced strong desires for getting training in assessment because, to them, it might lead to promoting their LAL, classroom-assessment practices, and students’ quality of learning. They were also required to elaborate on their specific training needs. Although three respondents did not provide any clear response to this question, the rest expected to receive training in some assessment skills including various formative assessment methods and techniques, test and scale development, item writing, and score interpretation. Concerning her specific ATNs, I5 stated:

I like to learn basically how to apply formative assessment in my classes because I have always used summative assessment to evaluate my students’ performance. Although I assign some scores to students’ class activity and attendance, I know what I do is not systematic or scientific.

I2 called for training programs that mainly focus on applied aspects of classroom assessment rather than theories and principles: “We are fed up with various theories of language testing. I suppose we did not learn how and where to apply those theories. I am eager to get training in anything which can be used in classrooms.”

Discussion

The current study sought to examine Iranian university English instructors’ assessment training experiences, classroom assessment practices, and ATNs. The results of the study showed that the instructors had received insufficient assessment training (specifically in classroom-based assessment practices), had low LAL, and had failed to put their limited testing and assessment knowledge into practice because they had solely been exposed to various theoretical assessment lessons in the limited courses they had taken in their undergraduate and post-graduate studies. Similar findings have been reported in studies conducted in other settings (e.g., Fulcher, 2012; Jin, 2010; Vogt & Tsagari, 2014). Jin (2010), likewise, attributes the failure of enacting language instructors’ assessment knowledge in classrooms to the limited time devoted to classroom practice in language testing and assessment courses. The results, however, are not supported by Lam’s study (2019) in which university instructors in Hong Kong were reported to have high LAL for receiving professional training in language assessment. This difference might be explained by the fact that instructors in this region are mandated to pass the Language Proficiency Assessment for Teachers Test to be qualified officially to start their career (Coniam & Falvey, 2013). Therefore, taking professional assessment training to prepare for the test appears to be necessary for the instructors. On the contrary, getting such a qualification is not considered a job prerequisite in the Iranian context. Besides, assessment training programs offered to preservice instructors in Hong Kong, unlike in Iran, are reported to be comprehensible and efficient (Lam, 2015).

The results of the study also revealed that the participants, despite their lack of assessment training, had refrained from using other resources to compensate for their insufficient LAL since they were not interested in the testing and assessment area and also had to comply with the testing regulations adopted in their universities. This is not consistent with the results in Tsagari and Vogt’s study (2017) where the instructors were reported to resort to books and recently-published papers and turn to their colleagues for practical advice in order to make up for their low LAL.

Another important finding of the study was that a great majority of the respondents (nearly 90%) expressed their desire to get assessment training. It appears that they assumed taking efficient assessment training programs to be effective in addressing their assessment needs and, consequently, enhancing their assessment literacy competence. As Tajeddin et al. (2011) concluded in their study, taking assessment training programs can help untrained or insufficiently-trained Iranian teachers develop a more profound understanding of different language proficiency concepts and make, for instance, more insightful and reliable raters through mainly focusing on macro-level and higher-order components of language while assessing their students’ performance.

On the other hand, the teachers mainly showed unwillingness in taking advanced and rigorous training programs and required basic training in content and concepts in assessment, purposes of testing, and classroom-based practices owing to their disinterest in the language assessment area (i.e., a personal factor) and insufficient support from their universities (i.e., a contextual constraint). This is in line with the findings reported in the study by Yan et al. (2018) in which the participants mainly tended to take less advanced assessment training courses to improve their LAL and, consequently, classroom practices. Yan et al. also argued that the tendency to get basic rather than advanced training can be accounted for by personal factors and/or contextual constraints. It accordingly seems that the university instructors may reinforce their interest in promoting their assessment knowledge and skills if more emphasis is placed on their assessment competence in their workplaces and adequate support and budget are provided for them to improve their LAL. A lack of support as well as strict regulations set by universities may discourage instructors from improving their LAL and assessment practices because the instructors are generally graded and evaluated based on the quality of their publications rather than on classroom practices (Mohrman et al., 2011).

More support and emphasis on LAL may reinforce the instructors’ interest in getting more advanced assessment training and induce them to pursue more recent and novel approaches to language assessment (Lam, 2015). For instance, they may strive to practice assessment for learning to support students’ learning and benefit from their assessment results to improve the quality of their teaching. Also, they may resort to the sociocultural theory of language teaching, learning, and assessment to assist their learners to move through their zone of proximal learning through constructive feedback on their performances and scaffolding. The tendency to grow such skills was also pointed out by the instructors who voiced their desire to learn to practice formative assessment.

The results also showed that when the interviewees were required to voice their specific ATNs, some of the respondents were found to be hesitant to answer. This supports Tsagari and Vogt’s (2017) study in which the language instructors failed to specify their ATNs clearly. As Hill (2017) argued, the difficulty to know ATNs appears when instructors fail to employ their assessment knowledge in classrooms or when they lack skills to elaborate on the efficiency of their classroom assessment practices.

Conclusion

The study attempted to explore university English instructors’ assessment training experiences, classroom assessment practices, and ATNs in Iran. In general, the findings revealed that the instructors had not received enough training to promote their LAL and classroom-based assessment practices because they had solely been exposed to language assessment principles in the limited courses offered to preservice teachers in universities, which had mainly revolved around concepts and theories of language assessment and had given short shrift to the practical aspects. In spite of this situation, the instructors had a stronger desire for one-to-two-day training programs (i.e., basic training programs) rather than advanced ones lasting more than three days. This tendency might be ascribed to different personal and contextual constraints including the instructors’ disinterest in the language testing and assessment area and lack of support from universities.

The study, however, is subject to some limitations that could be addressed in future research. First, it is a small-scale study with 68 participants who filled out the questionnaire and eight interviewees. Moreover, some terms used in the questionnaire (e.g., basic and advanced) may still look ambiguous, although they are quantified by being day-based. This ambiguity may give rise to varying interpretations and, consequently, different responses from participants.

Despite such limitations, the study may have some practical implications to enhance assessment training for university English instructors in Iran. For instance, the results obtained in the current study may contribute to growing the body of knowledge in the related literature. They may also raise teacher educators’ awareness of the Iranian university instructors’ LAL, assessment training experiences, classroom-based assessment practices, and ATNs. This awareness might induce them to design and implement more efficient assessment training programs in line with instructors’ lacks and actual needs. Further, the results may encourage Iranian university administrators and department heads to give more weight to their instructors’ assessment practices, to consider practical and effective assessment training programs for the preservice and in-service instructors, and to provide enough financial support for them to promote their LAL.