Introduction

In her article about doing research with children, Punch (2015) states how, in an adult-dominated society, children are not used to freely expressing their views or to being taken seriously by adults. Typically, there has been an adult-centeredness in matters that concern children directly, and very rarely, their voices are heard. In the case of including English in the elementary school curriculum in Colombia, for instance, voices from experts, scholars, teachers, and adults, in general, have been consulted, but children have not been asked; their voices have not been included. This article presents a research project carried out with children and for children, not only about children; a research project that asked them their views about English in their everyday lives and about the process of learning and teaching this language at school. Two primary purposes guide this article: first, the description of this research project and its findings; second, a reflection on the teaching of English to children and an invitation to question our adult views based on theirs. What can adults learn from children, and from what they have to say? Are young learners considered active participants in the process of education?

This article will be structured as follows: first, a description of the research project that includes objectives, theoretical framework, data collection instruments, and results supported by evidence from drawings, pretend plays, and conversations with the children; the article will conclude with a reflection about English teaching to children in our context.

Background

This study was conducted in Medellín, Colombia, with elementary school children from public and private schools. In this context, English can be considered a foreign language since the language surrounding students and the one in which life unfolds is Spanish; English is a school subject, and most children in public schools have little exposure to the language at school and little access to the language outside the school context. Even though it is the medium of instruction in some private schools, and is considered a second language, this is not the case for most public elementary schools in the city.

Local researchers have found a gap in the teaching of English in public and private schools regarding the teachers’ language proficiency and use of English in classes, the access to professional development programs, and teaching resources (Bastidas & Muñoz-Ibarra, 2011; Correa et al., 2012; González, 2010). Researchers agree that most teachers in public primary schools are teaching English because the law imposed it, but in most cases, primary teachers do not have the necessary preparation to face this task since they hold undergraduate or graduate degrees in areas other than foreign language teaching. Besides, they are responsible for teaching all subjects (math, social studies, physical education, English, Spanish, and others). English lessons are held once a week, usually for 45 minutes, with overcrowded classes of 45 to 50 students. Activities carried out in those lessons are mainly affective or organizational; translation is used to ensure understanding and teachers often model and organize, while the learners generally answer the teacher’s questions, repeat individually or chorally, or copy from the board.

As can be seen, the teaching of English in elementary schools in our context has been explored and insights have been gained from the perspective of researchers and teachers. We know what teachers think and do, but we do not know what children think or feel; their voices have been missing. Although their views can contribute to making classrooms better for learners, they have not been included so as to express their ideas in processes of planning, assessment, or even research. It is precisely within this framework, that a group of researchers at Universidad de Antioquia decided to conduct this study to open the road of exploration of children’s attitudes, beliefs, and information regarding English and the processes of teaching and learning it in the city. We acknowledge that children’s views of teaching and learning can inform curricular, methodological, and pedagogical decisions that affect children directly. Those views can also help adults to question their beliefs and practices regarding English teaching. If we want to move towards educational processes that are truly learner-centered, the voices of those learners should be seriously considered and made visible.

Thus, we decided to explore children’s perceptions through social representations (hereafter SR), as this concept encompasses attitudes, beliefs, interpretations, and information young learners have. Even though the importance of the study of SR in the field of education in general and foreign language education in particular is undeniable, there are very few studies about this specific topic with children in Colombia. So, the study presented here is a contribution to the field of foreign language teaching as it focuses on the viewpoints of children and opens the path to future research.

The purpose of the study was first, to explore children’s SR about English in their everyday lives and about the processes of teaching and learning it; and second, to try to derive possible implications that these representations would have for the teaching of English as a foreign language (EFL) in our context to illuminate decision-making at the level of classroom practices and policy-making processes.

Theoretical Framework

Social Representations

The concept of SR, one of the objects of study for social psychology, is one of the underpinnings of this project. SR were first studied and conceptualized by the social psychologist Serge Moscovici in his 1961 doctoral thesis where he claims that reality is a social construction arising from the interaction among subjects belonging to a group, and that these individuals, in turn, rely on this construction to develop their subjectivity and their position in the world.

In the words of Sotirakopoulou and Breakwell (1992), SR become concrete in the ideas, beliefs, values, practices, feelings, images, attitudes, knowledge, understanding, and explanations about a particular social object.

Conversely, Jodelet (1991) defines SR as images that summarize diverse meanings that allow people to interpret social events; they are categories that can be used to classify situations, circumstances, events, and people with whom we interact. Both Moscovici and Jodelet highlight the importance of the social nature of knowledge construction and acknowledge the critical role played by the context in the construction and interpretation of SR.

In the same vein, Howarth (2006) characterizes SR as being the products of the interaction among individuals, that is, collective meaning construction on objects that allow for the identification of what is relevant to individuals in a given group and how they are affected by them. SR give an account of what things are truly real or valid for a group or society. Similarly, for Araya-Umaña (2002), SR are mechanisms of classification and interpretation built within a community and allow us to define and make sense of the world we live in.

Araya-Umaña (2002) defines three dimensions of an SR: attitude, information, and field of representation. Attitude is the affective element of all SR. This component is always present and is the most evident of the three dimensions since it is expressed through emotions. Although attitude is present in all SR, this alone does not constitute the SR. Information refers to the knowledge that a group has about a social object. This dimension shows prejudices and stereotypes people might have about social phenomena. The field of representation is the dimension in which attitude and information are hierarchized and systematized, giving place to opinions, beliefs, and understandings. These elements allow the creation of conceptions and positions towards real-world issues. This three-dimensional framework will be used to present the findings of this study.

Social Representations, Education, and Foreign Languages

Howarth (2006) points out how the field of SR is continuously growing, and, in the last 40 years, has interested new researchers from all over the world, especially Europe, South America, Australasia, and even the USA. One likely reason for this expansion is the richness that this concept offers in reading and interpreting social realities and phenomena. Its multidisciplinary nature makes it a complex, polysemic notion that provides insights about different issues in different social and human sciences, including education and foreign language teaching.

In education, Jodelet (2011) highlights the appropriacy of the SR approach as an instrument and a mediation well suited to the multiple problems tackled in the field. SR are valuable in education because they allow an approximation to teachers’ and learners’ understandings of events in their environments and shape the way they act. The flexible nature of SR can be used to analyze various aspects of school life including the curriculum, interactions, the functions and purposes of education, and educational policies.

According to Jodelet (2011), in addition to giving an account of the conceptions that are held about educational realities and allowing their interpretation, SR have a pragmatic impact and contribute to shaping practices; also, exploring and analyzing SR sheds light on how these processes are perceived and how they can be modified.

Similarly, in the field of foreign languages, SR have been the object of study both for linguistics and language teaching. In this regard, Castellotti and Moore (2002) point out how sociolinguists have studied people’s attitudes and representations regarding, among others, languages and their nature, position, or function. Concerning the teaching of foreign languages, the authors show the significant influence of the learners’ representations on the language learning process since they can reinforce and enhance it or, on the contrary, inhibit it. The study of representations provides useful insights on both perceptions and practices in foreign language teaching and have allowed the exploration of a wide range of diverse themes that include, but are not limited to, teachers’ beliefs (Gabillon, 2012), culture in EFL classrooms (Menard-Warwick, 2009), identity issues in textbooks (Yen, 2000), and the perception of preservice teachers about racism and ethnocentrism (Carignan et al., 2005). As can be seen, SR is a multifaceted concept that lends itself to explaining and comprehending complex educational phenomena.

It is this connection to education in general, and to learning processes in particular, that makes SR a central and valuable concept for this study. The analysis of children’s perceptions of teaching and learning English can inform classroom practices, decision-making processes about education policies in foreign languages, and the relevance to the context where such policies are implemented. Following Castellotti and Moore (2002), the importance of SR for educators lies in the fact that they would allow teachers to understand some language learning phenomena, and to implement suitable teaching activities.

In the same vein, Kuchah’s (2013) study involving young learners and their teachers in identifying good practice reveals that both teachers and learners have their own perceptions about what constitutes good practice, and those views (sometimes convergent, and sometimes divergent) have more impact on the life of the classroom than the guidelines established by the Ministry of Education. The author suggests that classroom practices should be grounded in the sociocultural realities experienced by the learners, and even be elicited from them. Hence, the importance of doing research that includes the voices of children on this issue and gives them the opportunity to express what they think.

The Study

The core question that guided this study was: What are the SR that children in private and public schools in Medellin have regarding the English language and the processes of teaching and learning it? We wanted to explore children’s views about the importance of English in general and in their everyday lives, what they use it for, and what they think about the teaching and learning of English and its significance in their lives.

A qualitative interpretive research methodology was used in the study, and within this paradigm, the grounded theory methodology was selected to analyze data. Strauss and Corbin (1998) state that grounded theory is drawn from data, offers insight, and enhances understanding of the object of study. The authors also highlight that theory derived from data is more closely related to and resembles reality. In this study we aimed at understanding the meanings and interpretations of children and getting close to their SR regarding the teaching and learning of English. To do this, a grounded theory analytical process was used as categories emerged from the data and were not previously established. The project was developed in four stages. First, participants were selected and contacted: two private and two public elementary schools in the city were selected, and in each of them, three groups of children from first, third, and fifth grade were randomly selected to participate. Sixty children altogether participated in the project. Their parents signed consent forms before the implementation of the research. After this, data collection took place.

Given that this study aimed precisely at delving into children’s ideas, attitudes, and interpretations, it involved the implementation of data collection techniques that allowed us to come close to the children in a non-inhibiting way, namely, drawings and pretend play sessions, both accompanied by a conversation with the children to unveil the meanings they wanted to convey. Data were collected in four different sessions in every school where we worked with the groups corresponding to first, third, and fifth grades separately. The purpose of the first session was to get to know each other, explain the purpose of the work to be done, have children get familiarized with the researchers and the tools to be used like tape recorders and video camera so that these devices were not a cause of distraction in future sessions. In the second session, children were asked to draw the English class, and then there was a semi-structured interview with one of the researchers; the third session was about pretend play: Children were asked to “act out” one English class they liked, and one they disliked. Video recordings of both were kept, and a conversation about these dramatizations took place afterward. The final session was a closure in which the children presented their drawings as in an art exhibit, followed by viewing the videos and a conversation to collect their final remarks and show appreciation for their participation.

After obtaining the data and classifying the information by institutions and grades, we created an identification code for each one and we started the analytic process. For this, we used NVivo software, which allows uploading the data in their original format, that is, the drawings scans, scripts, and videos of the pretend play sessions, and the transcripts of interviews conducted after the drawings and pretend plays. Once the information was organized, and coded, we used an inductive approach to data analysis (data-driven), as categories emerged from the data. This process implied open categorization, making memos or preliminary elaborations and interpretations of data, identification of a core category, and establishing relationships among categories, within the framework of grounded theory presented by Creswell (2011).

Data Analysis

Analysis of the Drawings

Once the drawings were organized and properly coded, we analyzed them as visual texts, trying to make sense of the symbols, signs, and messages, that were present in those depictions of the English class. We use the term “visual texts” in the sense that Albers et al. (2009) use it, referring to “a structure of messages within which are embedded social conventions and/or perceptions, and which also presents the discourse communities to which the visual text maker identifies” (p. 239).

We used scheme analysis (Sonesson, 1988) as a reference for interpreting the drawings and their messages. These schemata refer to traits or the organization of elements found within a visual text, which defines its content and meanings. Based on the author, we analyzed the following schemata in the drawings: (a) principles of relevance, which include intensity of shapes, volume, repetition, colors, exaggeration and distortion of human features, size of human figure; (b) body scheme, which includes hair, body shape, directionality, clothing, and body parts; (c) behavior, which includes setting, actions, roles and interaction with others; (d) activities, which include the location of people involved in the drawings (students and teacher), active or passive movement, and so on. The Appendix illustrates how these drawings were analyzed. From the analysis of those schemata, categories emerged.

Analysis of Pretend Plays

Every pretend play session was video-recorded, and each video text was transcribed in the form of a script that included actions and dialogue. The analysis of the data collected through the pretend plays was based on the content of such scripts. We identified recurrent aspects present in the way girls and boys assumed each character in the game. The framework of analysis proposed by Sierra-Restrepo (1998) was used for analysis. It focuses on actions, characteristics, expressions, relationships, and interactions between participants. With this framework we identified the role of students and teachers, the types of interactions that took place, the rapport between teachers and students, the kinds of activities and materials used in the classes, and the language of instruction, among others. Based on the analysis of those elements in each of the scripts, we drew closer to children’s thoughts and feelings about the English class.

Categories emerged from the analysis; they were saturated with instances from all the sources (drawings, pretend plays, interviews), then refined and triangulated to obtain the findings presented below. Although the examples from data presented to support the findings belong to one of the data sources, the findings condense the results obtained from analyzing all the sources used and are not limited to one or some of them.

Triangulation was ensured by the researchers’ perspectives and different information sources, namely, drawings, pretend plays, and conversations with the children. Findings were condensed in the three dimensions of an SR: attitude (what they feel), information (what they know), and field of representation (what they believe or interpret; Araya-Umaña, 2002).

Findings

What They Feel

One of the dimensions of SR, is attitude. It refers to emotions and feelings towards a social phenomenon or event. In this case, both public and private school children reported having a positive attitude towards English and the English class. Concerning English, they expressed that it is a very important language, and there is a need to learn it (see below “what they believe or interpret”). Regarding the English class, there was a generally positive perception of the activities developed, and the class atmosphere was described as pleasant.

Researcher: Decime, ¿por qué decidiste dibujar esta clase de inglés y no otra? [Tell me, why did you decide to draw this class and not another one?]

Student 1 (Grade 3, public school): Porque, no, porque me gusta, el momento en que ella llega es como algo alegre, como que uno cambia de clase, y ya es más divertida, y ya no hay que escribir tanto. [Because I like it; the moment she arrives is like something happy, one changes to another class and it is more fun, and you do not have to write much.]

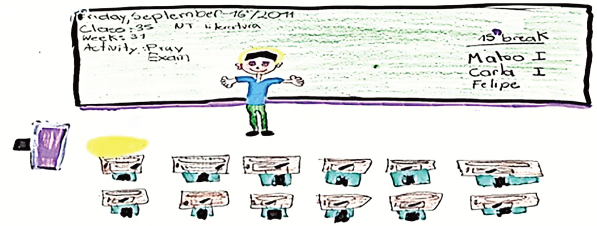

The previous quote summarizes two recurrent aspects highlighted by children in conversations: First, their positive attitude towards the English class and most of activities, and second, their dislike for writing activities in class. They refer to those activities as “copiar” (copying) and they consider this a boring class activity that takes a considerable amount of class time. In general terms, the English class was perceived as a cheerful, relaxed, agreeable moment that was different from the rest of the classes in the school day. Most children expressed through drawings and in the conversations how they enjoyed the classes and the activities proposed by their teachers. The atmosphere of classes is perceived as positive; children in public and private schools enjoy activities like games and songs (see Figure 1). They feel that the class environment is not stressful, and they do not find the English class especially difficult or unappealing.

Concerning the attitude of teachers, children presented them as displaying a positive attitude, most drawings show teachers with smiley faces, and children used the adjective “feliz” [happy] to describe them. Based on the analysis of pretend plays, we can state that when dramatizing the English class they liked, teachers were represented as having a respectful, kind attitude towards students, and, in turn, children also had a positive attitude towards the class and the activities. From the interviews, we could infer how children established a causal relationship between children’s behavior and teachers’ positive attitude. Children repeatedly expressed how, in order for the teacher to be in a good mood, their behavior was essential. Describing his drawing, (see Figure 2) a third-grade boy stated:

El dibujo consiste en cuándo está el teacher feliz y cuándo está enojado. Dependiendo de nuestro comportamiento se enoja o se pone feliz. Feliz, nosotros estamos escribiendo, terminamos rápido, nos desatrasamos, todo. [The drawing represents when the teacher is happy and when he is upset. Depending on our behavior, he gets mad or happy. Happy, we write, finish quickly, catch up with work, everything].

It is striking to see in Figure 2 how, when the teacher is happy, children are represented as if they were a group of little immobile “stones”; conversely, at the bottom, the teacher’s face changes when children are raising their hands and moving. This seems to indicate that a passive role from children is required for the teacher to be “happy,” and also how children’s positive behavior is rewarded by a positive attitude from the teacher that, in turn, becomes a critical element for a good classroom environment. This highlights the connection between teacher’s positive attitude and learners’ behavior.

The interrelation of affective factors and second/foreign language learning has been the object of study of researchers from different fields. In educational psychology, Wang and Wu (2020) argue that the learning outcome of the second language acquisition is greatly influenced by the affective factors of the learner, such as motivation, attitude, anxiety, and empathy, to name but a few. In the field of language teaching, Kumar (2017) also points out that emotions filter all learning and cognition, so the study of affective factors in second language learning is quite significant. The impact of affective factors on the learning process makes evident the need of provoking and sustaining positive attitudes towards learning and teaching.

What They Know

Based on the information children acquire from the adults around them, as well as media and propaganda, children consider English a very important language in the world and derive from there the importance of learning it. For instance:

Como el inglés es el lenguaje universal y mi mamá dice que yo soy muy disciplinada, entonces… [as English is the universal language and my mom says that I am very disciplined, then…]. (Student 4, Grade 5, private school)

Pues, es otra puerta que abrimos, porque cada vez que uno habla inglés es abrir una ventana. [Well, it is another door we open, because every time one speaks English is like opening a window.]

Researcher: ¿Para qué aprender inglés? [Why learn English?]

Student 5 (Grade 5, private school): Para que nosotros avancemos y ellos nos puedan entender. [So that we move forward, and they can understand us.]

These quotes show how English is seen as the requirement to connect to the world, since it opens doors probably to new possibilities, to a good job, to a better life. The last quote establishes a difference between them (English-speaking people) and us (Colombians) and highlights how learning English is for us a sign of progress, a possibility to understand them, and also a requirement as we have to learn this language if we are to move forward.

When asked about the use of English in their future, children repeatedly answered:

Researcher: ¿Y a uno para qué le sirve por ejemplo aprender inglés? [And what is the use of learning English?]

Student 4 (Grade 5, public school): De pronto cuando trabaje, una reunión o algo, a veces es en inglés. [Maybe at work, meetings sometimes are in English.]

As can be seen, the discourse of children in public and private schools has been permeated by the values and views prevalent in their contexts in which the job market is one of the main reasons for learning English. The images presented to children in our context highlight the importance of learning English, not an additional language, and the purposes for learning it are usually instrumental, being access to a better job the most recurrent.

Regarding the context for learning English, in general terms, children see it as circumscribed to the classroom and to the use of books and dictionaries. Figure 3 illustrates this point.

Children also show awareness of the importance of the context when learning a language. In their own words:

Es que es muy difícil aprender uno inglés en un lugar en el que uno no ve inglés, todo no es inglés como en Estados Unidos que cualquier letrerito está en inglés, todo está en inglés. Es más difícil. [It is very difficult to learn English in a place where one does not see English, everything is not English as in the United States where any little sign is in English, everything is in English. It is more difficult.] (Student 1, Grade 5, private school)

Yo pienso que se aprende como el español estando rodeado de muchas personas que lo hablen, entonces uno se acostumbra. [I think that English is learned as Spanish, being surrounded by many people that speak the language, then, you get used to it.] (Student 5, Grade 5, public school)

Children consider that learning English requires being surrounded by a supportive environment where the language is used and, for that reason, it is difficult to learn this language in our context where exposure to the language outside the classroom is scarce.

In contrast to what they think about the process of learning the language and about the need of being exposed to it, children in elementary school know from their experience in class that learning English implies repeating, writing, and memorizing lists of words and grammar structures even though they consider that the purpose of learning a language means being able to speak it fluently in interactions with others: “Saber inglés es como un idioma y una forma de comunicarse con otras personas.” [Knowing English is like a language and a way of communicating with other people.] (Student 3, Grade 3, private school).

As to learning,

Researcher: ¿Tú cómo has aprendido inglés? [How have you learned English?]

Student 2 (Grade 3, public school): Porque la profe nos y repite, y repite, y ya nosotros lo sabemos, entonces cuando ya repetimos, y repetimos, ya primero nos sale mal porque no hacemos bien la pronunciación, y después ya que uno repite y repite ya, ya lo sabe bien. [Because the teacher repeats, and repeats, and we learn it, so when we repeat, and repeat, first it turns out badly because we do not pronounce well, and then, as you repeat and repeat, you learn it.]

There seems to be a gap between children’s views of English, what it means to have a good command of the language, and what happens in class. English for life outside school is one thing, and English at school is another. This information children have about language itself and about teaching and learning processes is nourished by their experiences inside and outside schools and what they hear from adults and the media around them.

What They Believe and Interpret

This third dimension, field of representation, is related to what children believe and interpret. The findings about English, its usefulness in children’s lives, and what they believe about the processes of learning and teaching it are presented through the following analogies: learning as “echo”; teaching as a “power tool”; and English to “survive” or “to live and interact.” After analyzing the data and keeping in mind that SR are images that help explain the social phenomena studied, we decided to select images that captured the essence of the SR children had regarding English in their lives, and what learning and teaching meant to them. After establishing relationships among categories that emerged from the drawings, pretend plays, and interviews, the images that better depicted children’s beliefs and interpretations were learning seen as “echo” as it represents the idea of repetition, prevailing in the data; teaching as a “power tool” as this image accurately captures what children think about teaching and how they interpret their rapport with teachers; and English to live or survive, as a powerful image to show the difference between the views of children in public and private schools.

Learning as “echo.” As previously stated, learning is perceived by children in both private and public schools as a process of memorizing lists of words and structures, and being able to repeat them on an oral or written test as proof of their learning.

Researcher: ¿Cómo se aprende inglés? [How do you learn English?]

Student 2 (Grade 5, private school): Escribiendo, memorizando, hablándolo, dibujando también hay veces. [Writing, memorizing, speaking, and sometimes drawing.]

Researcher: Y fuera de que una persona le repita a uno la palabra y uno se la vaya aprendiendo, ¿cómo más se puede aprender inglés? [And apart from having a person repeating the word for you to learn it, how else can you learn English?]

Student 3 (Grade 3, public school): Que uno escuche una palabra y todos los días la repita. [When you listen to a word and repeat it every day.]

These answers seem to indicate that English teaching emphasizes activities of mechanical repetition and promotes children’s echoing of what teachers present in class; there are no opportunities to use language creatively, use imagination, or express feelings or ideas. It can be inferred that language is conceived as a code to be mastered, and repetition is the most effective way to achieve this goal. Both public and private school children drew and described lessons where the teaching of grammar and vocabulary was the focal point, and their answers emphasized the need to memorize and repeat those lists.

Even though memorization and repetition are cognitive processes needed for learning a language, it should go beyond mechanical reproduction and promote meaningful uses of the language and social interactions within creative and flexible environments. This was also supported by children when they requested more playful class activities.

It is essential then to transcend the mere repetition of words to promote meaningful uses of the language at the level of children. Learning a language should be more than just “echo.”

Teaching as a power instrument. Power issues are present in classrooms, and children made them evident in their drawings, pretend play sessions, and conversations. Drawings usually depict a teacher in front of the class with the board behind, and children organized in lines working individually indicating a vertical relationship between teacher and students; children are usually seated and paying attention to the teacher with no interaction among themselves (see Figures 4 and 5).

Drawings portray children sitting down, writing, and sometimes raising their hands. Individual work is recurrent in drawings and in the pretend plays indicating how children’s role is usually a passive, non-interactive one.

This teacher-centeredness depicted in the drawings is reinforced by expressions children used to refer to what the teacher does in the classroom. Common expressions like “nos pone a aprender, nos pone a escribir” (the teacher makes us learn, or write) show that power lies in the teacher and is not limited to instances of evaluation but has permeated the teaching process as well. Only one of the drawings portrayed a child writing on the board; this is definitely the teacher’s action zone that creates distance with well-defined spaces for students and the teacher. These invisible limits reinforce a vertical relationship between the teacher and the children. The classroom setting is usually very similar in all the drawings, and some drawings portray little teacher-student interaction, let alone students’ interaction. Both the drawings and pretend play sessions present teacher-centered lessons. The teacher oversees planning, teaching, evaluating, and discipline, leaving children a passive role of obedience and acceptance. As a result of this, some children report how learning English implies being attentive, silent, and quiet. Their role is a passive one.

Researcher: Tell me, how do you learn English?

Paying attention, listening to the class, having a good memory capacity. (Student 1, Grade 3, public school)

Paying attention to the teacher. (Student 2, Grade 3, public school)

Listening, not speaking, paying attention, and everything. (Student 1, Grade 5, public school)

More active, interactive, collaborative activities and learning environments are required for children to see English as a language that accomplishes multiple social purposes and to promote more social learning processes with children as the center of the activities. It is important to offer children opportunities for more equitable, less vertical relationships to learn with each other and from each other.

One of the instruments traditionally used by teachers to exert their power is grades. However, in this project, we could observe that when teaching, this power was also evident in the control of discipline in the classroom through the punishment of disruptive behavior and the widespread use of writing as punishment. The following excerpt from a pretend play transcript illustrates this point:

The teacher (N1) appears with a threatening attitude and points at N2 with her right index finger.

Teacher: Sit down! Sit down!

N2: OK, OK! (N5 goes to his desk)

The teacher stands in front of the students. N3 raises his hand.

N3: Can you explain this to me, please?

Teacher: No! Silence! (Pointing his index to N3).

N2: Teacher, can I go to the board?

Teacher: No! (Pointing his finger energetically at N2).

At the end of this pretend play, students decided to go to the principal to express their unconformity with the English class.

Now, N1 assumes the role of principal for a few moments. The principal approaches the children.

N2: The English teacher is not teaching us anything and scolds us.

N3: And it is English class, not scolding class.

N4: And she does not even explain to us.

Principal: I am going to talk to the teacher. He leaves, and students return to the classroom.

The teacher (N1) reappears where the children are.

Teacher: Then you are going to write a book of at least five pages.

N4: No teacher!

This is a depiction of the power teachers have in the classroom, the passive role of obedience expected from students, and what they stated in several instances of conversation: writing is used as punishment. It also shows how students are empowered to take actions leading to change. They voice their inconformity with the principal and, aware of the situation, they act upon it and change it. They are not passively accepting the actions of teachers; they are moving towards change.

Fortunately, this teacher power is also a possibility; it can be used to make a difference, and some teachers actually do. Even though one might expect better teaching practices in private schools given their favorable conditions in terms of resources, equipment, facilities, and prepared teachers, we found that positive teaching practices took place in both contexts regardless of their conditions. Children in private schools reported visits to the computer room, song festivals, and connections to other content areas in the English class, and public-school children mentioned the use of some games in class and connection to other areas like physical education.

Teachers make the difference with their ability to seek appropriate pedagogical and didactic strategies to bring children closer to the foreign language. The disparity in teacher preparation and access to equipment and resources means that the processes are different in the public and private sectors. For instance, the use of English in class is more evident in private schools than in public ones. In the drawings, the children reflect this (see Figure 6), and also in the pretend plays in which the children of one of the private schools used English when dramatizing the English lesson. This means that children in private schools have more exposure to the language at school and outside school as well, as will be presented in the next section. A reason for this might also be that teachers in private schools hold an undergraduate degree in foreign language teaching, whereas most of the teachers in public schools hold degrees in many different fields, but not in language teaching. Therefore, these teachers use different methodologies and use a different language as the means of instruction.

Figure 6 Excerpts of Drawings of the English Class (Boards): Private School (Left) and Public School (Right)

English as a tool to “survive” or to “live and interact.” This finding reveals a big difference in the way children in public and private institutions conceive English. Mostly for the former, English is a tool to pass exams or to obtain passing grades at school, that is, it is a tool to “survive” in their academic environments. In some cases, English is also a tool to “serve” others (foreigners) that come from abroad, and we should be prepared to understand them and determine what they need. In contrast, for the latter, English is a tool to read instructions, play video games, talk with relatives who live abroad, or interact with others when they travel. These two different perspectives reflect the possibilities children have access to or are deprived of depending on their contexts and socio-economic conditions. Table 1 presents some answers about the use of English in their lives.

Table 1 Children’s Answers About English Use

| Children in private schools | Children in public schools |

|---|---|

| A veces en el internet hay cosas en inglés, entonces… [Sometimes on the Internet there are things in English, so…] | Para estudiar, para pasar todas las materias, y todos los años. [To study, to pass all the subjects, all the school years.] |

| Para escribir correos, para mandar cartas a Estados Unidos, para poder hablar con primas, tías. [To write emails, to send letters to the United States and talk to my cousins, aunts]. |

En un trabajo o en un restaurante, de pronto cuando viene gente del extranjero. [In a job or in a restaurant, or maybe when people come from abroad.] |

|

Nos sirve para cuando vamos a viajar. Por ejemplo, vamos a viajar a Canadá entonces allá podemos intercambiar frases y oraciones con las personas de allá. [It is useful when we travel. For example, we are going to travel to Canada, so there we can exchange phrases and sentences with the people there.] |

Para las clases y pa’ las notas. [For the English classes, and also for the grades.] |

Researchers that study SR have emphasized the influence of the context in which SR originate. Castellotti and Moore (2002) argue how these images are created, preserved, and spread in society through different means like media, literature, manuals, among others. According to the authors:

Representations vary according to learning macrocontexts, which include language teaching curriculum options, teaching orientations and relationships between languages both in society at large and in the classroom, and micro-contexts, which relate directly to classroom activities and the attitudinal and learning dynamics they set up. (p. 21, emphasis in the original)

Findings show that in our context, children see English as a universal language, as very important, as a window to another world or the door to the job market. These ideas circulate around them and are perpetuated by the educational system and the media.

This project arose from the need to open a space to listen to children’s voices about English teaching and learning in Medellín. We learned that it is necessary to develop research projects that can account for what children think and feel concerning education in our Colombian context, with a view to illuminating teaching practices and educational policies in this field. Research related to the teaching and learning of English in Colombia has focused mainly on the perceptions of adults and thus, research that includes and takes seriously the views of children is needed as it could inform changes in the content taught or in the materials and methodologies used. When we hear the voices of children, we can hear our own adult voices and stop for a moment to reflect and question them. How can positive attitudes be supported and enhanced? Is this the message we want to convey about teaching and learning? Whose interests are we serving? Do we want to maintain those power relations as they are? How can our beliefs and practices be transformed?

Conclusion

This article presented a qualitative interpretive study about the SR that children in elementary schools in Medellin, Colombia, hold regarding English teaching and learning. Drawings, pretend play sessions, informal conversations, and semi-structured interviews were used to collect data. Findings reveal that both teachers and children have a positive attitude towards the teaching and learning of the language. Children perceive English either as a tool to survive in the academic context (public school children) or to communicate with others (private school children). For the participants in this study, the learning process is circumscribed to the classroom setting and implies repetition and memorization of words and grammar structures. Vertical relationships between teachers and students are widespread, and little interaction is promoted in the English lessons.

One of the limitations of this study was the analysis of data coming from children in first grade, given that we found it was difficult for these children to separate the English class from the other school day activities, and also because more knowledge about the cognitive and developmental processes of this group was required to be able to interpret what they expressed. More research is needed concerning the methodological tools to be used with this group of learners and also in the analytical processes to unveil their meanings.

This paper is an invitation to further research that explores children’s interpretations, feelings, and thoughts regarding the learning and teaching of additional languages in our context. This may help overcome the adult-centeredness that has characterized research and teaching for so long.