Introduction

Students in secondary education today are usually skilful in the use of technology, and some studies have focused on the usefulness of this exposure to the media for the L2 classroom (Feng & Webb, 2020; Montero-Pérez, 2020; Webb & Rodgers, 2009b). Moreover, most schools are starting to normalize the use of technological devices in the classroom. Many teachers and educational researchers have seen an opportunity in this technological and media proficiency on the part of the students, and its acceptance on the part of the schools, as a way of taking advantage of the media’s intrinsic motivation for learners in English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching. As a result, this article presents the process undertaken to create and exploit a corpus of audiovisual materials (AM)-such as films and TV series-to use as a learning resource in the EFL classroom to improve language learning and the development of students’ communicative competence.

Recent studies have explored the benefits of using AM in the EFL classroom, such as the many examples of language use in real-life context they display (Peters & Muñoz, 2020; Puimège & Peters, 2020), the variety of topics they might tackle (Sert & Amri, 2021), the advantages of imagery for vocabulary learning (Webb & Rodgers, 2009a; Pujadas & Muñoz, 2020) and the possibility to use captions while viewing (Lee & Révész, 2020; Peters & Muñoz, 2020; Wisniewska & Mora, 2020). Films are usually intrinsically attractive (provided the topic appeals to the viewer) and they are said to be one of the most enjoyable and accessible forms of entertainment, which can work as a motivator and an educator for EFL students (Feng & Webb, 2020), enhancing the language learning process as long as appropriate materials are selected and suitable activities designed (Donaghy, 2015).

The main purpose of this paper is to explore how AM, such as scenes from films and series, can be selected, analysed, and exploited in the EFL classroom to develop students’ communicative and comprehension skills. The creation of a corpus of useful and exploitable audiovisual fragments will be explained, identifying and collecting examples of fragments of films and series that can be used to promote language learning. This could help other teachers by offering possible scenes to use in class that are also relevant in their professional contexts. Furthermore, the way in which the intrinsic attractiveness of audiovisual resources may improve secondary education students’ motivation and engagement will be highlighted.

First, there is a discussion of the theoretical framework behind the compilation of the corpus CAMELLS (Corpus of Audiovisual Materials for English Language Learners in Secondary) and its exploitation. Next, the methodology used will be explained, which was based on two surveys distributed to secondary education students to learn more about their likes and preferences on films, series, and EFL classroom activities. The process undertaken to choose scenes in the corpus will be described. Finally, the main findings will be presented, which stem from another survey done regarding the use of AM and other common practices in the EFL classroom. In this section, the CAMELLS corpus will also be presented, and some possible ways of exploiting it in the secondary education classroom will be discussed. The limitations and implications of the study will be highlighted in the conclusions section.

Theoretical Background

Making use of AM in the EFL classroom can present many benefits while learning the second language, as “meaning is communicated through moving images more readily than print because of its immediacy, making film literacy an incredibly powerful teaching tool” (Donaghy, 2015, p. 12). This means that the visual component of AM is likely to help with language acquisition, since the images “support the verbal message and provide a focus of attention” (p. 19). Moreover, these kinds of materials can be very useful, especially in terms of improving students’ motivation and engagement (Feng & Webb, 2020; Peters & Muñoz, 2020; Pujadas & Muñoz, 2020). Films and TV series will probably be intrinsically attractive to students, especially if they are interested in the topic. Therefore, a survey was designed (see Method section and Appendix A) to learn more about students’ interests and preferences. Motivation is said to be “one of the main determinants of second/foreign language (L2) learning achievement” (Dörnyei, 1994, p. 273), which means that if students do not feel motivated or are not engaged in the lessons, it will be more difficult for them to acquire the language. Dörnyei (1994) claims that there are three levels in the L2 motivation framework: the language level, the learner level, and the learning situation level (p. 279). These three levels were taken into account to try and increase the attractiveness of the content of the course under investigation by using authentic AM and visual aids and exploiting them to increase students’ interest and involvement.

Another benefit of the use of these resources can be familiarizing students with the English language in real-life contexts and situations for communication, so language learning can be improved by providing authentic input that might be hard to display through other materials (Alluri, 2018; Donaghy, 2015; King, 2002). Real-life audiovisual models of the foreign language can help develop comprehension skills, aside from providing different contexts for the development of activities. AM provide a clear context for the students to better understand and acquire vocabulary (Kalra, 2017) since multi-sensory input is likely to aid memory retention more effectively. Using AM helps train “verbal skills, writing, vocabulary, grammar and cultures,” but it is the teacher’s job to come up with activities that work these skills (Alluri, 2018, p. 148).

Furthermore, films and TV series make a great tool for intercultural communication, since they are “cultural documents” that help to communicate cultural values and customs to viewers, as well as making them “better understand their own culture” (Donaghy, 2015, p. 19). They also offer “an opportunity for being exposed to different native speaker voices, slang, reduced speeches, stress, accents, and dialects” (King, 2002, p. 511). This means that they are an appropriate and realistic source of representation of different Anglo-speaking countries with their different accents and registers, which is something required to develop students’ communicative competence and its sociolinguistic component. Also, “by introducing various cultures to students through films we can make students tolerant, liberal and sensitive to other cultures and respect them” (Alluri, 2018, pp. 148-149), which is something that must be taken into account since one objective as an EFL teacher is to develop students’ intercultural competence without prejudices or stereotypes.

The benefits of AM for promoting students’ communicative competence, their motivation and engagement, and their intercultural awareness have been well attested. As has been pointed out, when seeking to introduce AM in the EFL classroom attention has also to be placed on what use is made of such materials and how they are exploited. Ellis et al. (2002) argue that students will not achieve a high level of linguistic competence if there is not a focus on form in the EFL lessons. This means that teachers cannot rely on the film’s topic alone if they want students to acquire the language. In his words, “learners need to do more than to simply engage in communicative language use; they also need to attend to form” (p. 421). AM are a source of authentic language which can be brought and exploited in the classroom to foster communicative competence in line with communicative language teaching principles (Brown, 2007; Larsen-Freeman, 2014; Richards, 2006), but in order to be effective, students’ attention needs to be drawn to specific features of the language (Han et al., 2009; Izumi, 2002).

Through films and series students can be exposed to contextualized language and such input can contribute to developing their grammatical, discourse, functional, and strategic competences. This can be done through the use of input enhancement. Larsen-Freeman (2014) explains that “by highlighting . . . certain non-salient grammatical forms in a reading passage, students’ attention will be drawn to them” (p. 258), and thus, input enhancement is achieved. Han et al. (2009) points out the reasons why input enhancement should be used in the L2 classroom; first, learners may “lack sensitivity to grammatical features of target language input.” Secondly, “certain grammatical features in the input . . . are inherently non-salient,” so learners may not notice them. And finally, “learners’ first language may act as a hindrance to their ability to notice certain linguistic features in the input” (p. 598). When using AM, learners’ attention can be drawn to particular language features, for example through the use of subtitles: “movie subtitles through input enhancement can have a facilitative role in the achievement among the participants and it can affect their speaking ability” (Okar & Shahidy, 2019, p. 101); or by highlighting specific salient features as will be argued in the Findings section.

Previous research on the effects of AM on students’ acquisition of English as an L2 has pointed out the importance of such authentic input to be comprehensible and the actual impact on vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation learning. The input students are exposed to needs to be comprehensible, and for that, a vocabulary of the most frequent word families need to be covered by the films and series. Webb and Rodgers (2009a) determined that a lexical coverage of 3,000 word families would be necessary, concluding that “if 95% coverage is sufficient for comprehension then movies may be an appropriate source of L2 input for many language learners” (p. 418). In contrast, if 98% coverage is necessary then additional support should be given in order to ease comprehension, like pre-viewing activities or the use of captions or scripts (Webb & Rodgers, 2009a). Very similar results were found when investigating the vocabulary coverage of TV programs (Pujadas & Muñoz, 2020; Webb & Rodgers, 2009b). Combining visual and aural input might make comprehension easier than listening comprehension, since it may “effectively link L2 form with L1 meaning” (Webb & Rodgers, 2009a, p. 410), and that in an EFL context these materials could “improve listening skills, [improve the] learn[ing of] vocabulary,” and help “focus on specific language points” (p. 420). Pujadas and Muñoz (2020) argue that, even if students are motivated to use AM for language learning, some films or series might be too difficult to understand, and they showed how captions eased such comprehension.

Students’ vocabulary range has been shown to improve thanks to AM. Puimège and Peters (2020) explored the incidental learning of formulaic sequences (FS) from audiovisual input, and found that knowledge of FS benefits language processing in both native speakers and L2 learners and is a key predictor of L2 writing and speaking proficiency. Nevertheless, FS usually present difficulties for L2 learners due to their low frequency in texts. In the light of their results, Puimège and Peters concluded that “TV viewing can be a highly effective method for acquiring L2 vocabulary” (p. 546).

As regards the development of students’ grammatical knowledge, Lee and Révész (2020) argue that “captions cannot only facilitate the acquisition of L2 vocabulary but also have the capacity to promote development in L2 grammatical knowledge” (p. 642). Finally, Wisniewska and Mora (2020) examine the potential benefits of captions on pronunciation, finding that they enhanced “not only the ability to segment speech, . . . but also the ability to process speech faster and more efficiently” (p. 616).

Looking at the findings of all of these recent studies on audiovisual input for language learning, I think it could be affirmed that AM can be very useful in the EFL classroom if they are appropriately selected, and if they are suitably exploited. This paper aims to present the process of selection, analysis, and exploitation of AM in the EFL secondary education classroom.

Method

Instruments

Two surveys were designed with the purpose of creating the CAMELLS corpus and exploiting it. The first one was aimed at secondary education and baccalaureate students (i.e., 12- to 18-year-olds in Spain). It was sent to the participants through Google Forms in the students’ L1 (Spanish). The survey called for information such as age, gender, the academic year in which they were currently studying, and requested participants to name two or three English-speaking films and two or three English-speaking series they enjoy watching (see Appendix A). The main intention of this first survey was to take into account students’ preferences and find out what kind of films and series appeal to different ages in order to ensure that the clips to be used will actually be motivating for the students.

The second survey was carried out with the intention of finding out students’ opinion on using audiovisual resources in the EFL classroom and what kind of activities they find most engaging during these classes. This survey concerned three main points: the participants’ viewing habits as an out-of-class activity; the use of AM in their EFL classes; and the activities they usually carry out in the EFL classroom. It first asked how participants usually watch English-speaking films and series (if dubbed into Spanish, with English or Spanish captions, or in the original version) and why would they prefer to watch AM in English-if they did so. Then, if they ever use AM in the EFL classroom, and how they do so (similar to the first question). Finally, the survey requested students to grade typical EFL activities according to their level of engagement. It consisted of six linear-scale questions and three open-answer ones (see Appendix B).

Participants

Secondary education and baccalaureate students (i.e., 12- to 18-year-olds in Spain) participated in the first survey, while only fourth year secondary education students (i.e., 15-16 years old) took part in the second survey. The first survey received 46 responses (32 female and 14 male respondents) and 49 students participated in the second one.

Procedure for the Administration of the Survey

Responses to the first survey were progressively collected and then a list was made with the films and series that had more than one vote. Initially there was a great variety of titles, but most of them had been selected by just one person (since the survey was open-question, the responses had little cohesion), so only the titles, which had more than one vote, were selected (see Tables 2, 3, and 4). The titles in the corpus were intended to be used with fourth-year secondary education students (i.e., 15-16 years of age). However, since the sample would have ended up being too small if only the titles chosen by students of this age were considered, the ones suggested by students one year younger or older were also taken into account (considering that most answers had been given by third-year students).

Procedure for the Selection of Titles and Fragments

However, some of the titles chosen by fourth-year secondary education students were finally not used because of their topic or because of age restrictions, even if they had received many votes-titles such as It (which received four votes), Joker (four votes) or The Walking Dead (two votes). These are a substantial number of votes considering that the majority of films and series that the participants selected had just one or two, and that it was an open-question survey (that is, the participants could write down any title they wanted as long as English was the original language). I decided not to include these titles using my own criteria as a teacher, since I would not want the clips used in class to upset any student (both for moral and practical reasons; a frightening or generally uncomfortable clip would probably affect the students’ performance when carrying out an activity), and because there were many others to work with. Similarly, even if many titles from this final selection could be useful due to their content, there were also an ample number of them that I considered unattractive due to their lack of action and that were not used. Again, my own criteria were used for this, since the idea of something being boring or tedious is very subjective. The scenes considered non-engaging were the ones which included long dialogues with no action (for instance, some of these were found in the first episode of Peaky Blinders), that may not be appealing to students.

After this, I started watching the films and series on the final list and noting down different fragments that were expected to be both practical for English language teaching and engaging for the students. The fragments were selected taking into account two main elements: the topic(s) and the linguistic features present, which needed to follow the fourth-year standards in this case. To meet these criteria, the fragments had to include some sort of dialogue with useful language for the students (e.g., grammatical and syntactic structures, lexis), and also include interesting topics, ensuring that students would find them enjoyable.

Procedure for the Analysis of Selected Fragments

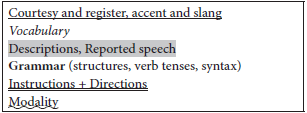

Then, the fragments selected (24 in total, as can be seen in Table 4 in the Findings section) were analysed. This entailed transcribing the corresponding script and highlighting different language elements (such as vocabulary, grammatical structures, and syntax, among others) that would be suitable for the academic year I was focusing on. A coding system was used on the scripts (see Figure 1) to highlight the main linguistic features that should be taught in the fourth year of secondary education. This could also make it easier for the learners to notice certain elements, if they also work with the scripts and not just with the audiovisual fragments.

Regarding the exploitation of CAMELLS, two different protocols were followed for the initial step of the development; either choosing a fragment that could be useful for a specific academic year and then coming up with an activity; or thinking about a convenient activity to work some particular features and then choosing a scene that could be employed for this. Due to the nature of this project and the corpus of fragments created, the first protocol was the one followed for the most part, so most of the activities are based on a previously analysed fragment. In regard to the second protocol (first coming up with an activity or deciding what the activity should focus on before having a scene for it), the scenes chosen included important grammatical and/or lexical features for the students’ level, as well as those that had relevant topics. The intention of the fragments chosen was to focus students’ attention on particular forms and make them notice them through input enhancement in subtitles and scripts (Okar & Shahidy, 2019).

Findings

In this section, the results of the two surveys conducted will be presented. Then, the corpus CAMELLS, which was compiled according to the results obtained from the surveys, will be described. The corpus presented in this paper can be considered a pilot version, since it is expected to be developed in the future through further research.

Results From the Surveys

In the first survey, 46 responses were received, most of them including 5-6 titles, so the corpus ended up with 67 film titles; there were 99 suggestions in total regarding film titles, but as this included the repetition of titles the final number was 67. The same goes for the series titles; there were 92 suggestions in total, but counting the repeated ones, it turned out to be 57 titles (Table 1). From the 46 responses, 27 (58.7%) were selected as a representative sample of the academic years under study: 11 from the third-year secondary education, 8 from the fourth-year secondary education, and 8 from the first-year baccalaureate.

Table 1 Summary of Results for First Survey on Students’ Choice of Audiovisual Materials (N = 46)

| Initial number of suggested film titles | Final number of film titles (excluding repeated ones) | |

|---|---|---|

| 99 | 67 | |

| Initial number of suggested series titles | Final number of series titles (excluding repeated ones) | |

| 92 | 57 | |

| Academic year of the participants’ responses considered | ||

| 3rd-year secondary education | 4th-year secondary education | 1st-year post-secondary education |

| 11 | 8 | 8 |

In regard to the second survey, results revealed that 28 out of 49 participants (57.15%) watch films and series in English as a leisure activity. The main reasons for this are that they believe watching them in English will help them learn and practice the language (Appendix C). They also acknowledged that they prefer hearing the actors’ real voices and original script because of problems like mistranslated puns. Therefore, more than half of the participants stated they would find watching films in English in the EFL classroom useful and enjoyable. Moreover, even if 21 participants declared they do not watch films or series in English for leisure, 43 out of 49 (87.75%) participants claimed to have watched films or series in the EFL classroom before.1

Regarding what kind of activities the students found most motivating, they indicated that they would like to break away from the routine of using their every-day English books and doing grammar exercises. They expressed they would like to be active participants in the EFL classroom and use different resources and materials. This is related to the question regarding students’ attitude towards watching films in English in the EFL classroom, since 10 participants (20.4%) claimed that they would enjoy watching videos or films and commenting on them. This information is further supported by the results obtained in the question “What would you change or improve about your English lessons?” More than half of the answers (30 out of 59) belonged to the group “more fun, entertaining, and interactive” lessons, and changes in relation to academic work and the use of AM in class was also demanded. In summary, the participants report they prefer more engaging and interactive lessons, less focused on grammar and more focused on speaking and games.

These results revealed that the lack of motivation for most students lies in Dörnyei’s (1994)learning situation level, which can be divided into three areas: course-specific motivational components, teacher-specific motivational components, and group-specific motivational components. Most of the answers expressed in the survey were related to course-specific motivational components, since students claimed to be displeased with the teaching method, the learning tasks, and the materials. Taking all of these data into account, one sees it can be affirmed that using audiovisual resources could help with students’ engagement, especially of an interactive kind in which they are active participants. This would make our lessons more effective in terms of language acquisition and motivation.

Description of the CAMELLS Corpus

After compiling the responses of the 46 participants of the first survey, the final count was of 67 film titles and 57 series titles, although many of these were selections with just one vote. The number of votes each title received was included in a table, ending up with 16 film titles (Table 2) and 16 series titles (Table 3), to make way for the next step.

Table 2 Film Titles in CAMELLS

| 2 votes | The da Vinci Code, Mean Girls, The Greatest Showman, The Notebook, Wonder, The Lion King, The Incredibles, A Monster Calls |

| 3 votes | The Hunger Games, Spider-Man, Five Feet Apart |

| 4 votes | Star Wars, Joker, It |

| 5 votes | Harry Potter |

| 6 votes | Avengers |

Table 3 Series Titles in CAMELLS

| 2 votes | Game of Thrones, The Walking Dead, Vikings, Grey’s Anatomy, Jane the Virgin, CSI, Raising Dion, Voltron: Legendary Defender |

| 3 votes | Shadowhunters, Glee, The Society |

| 4 votes | Peaky Blinders, Gossip Girl, 13 Reasons Why |

| 6 votes | Stranger Things |

| 8 votes | Friends |

Some problems were encountered during the first response count; for instance, many students had written down Avengers as their favourite film, which posed a challenge since there are many films related to this title (The Avengers, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Avengers: Infinity War, and Avengers: Endgame), and most of the main characters have their own film. There were also many students who wrote down titles of films belonging to this saga (such as Iron Man, Doctor Strange, and Spider-Man). Because of this, all of these titles were counted as belonging to the category of Avengers since they are all quite similar in their topics and style, thus of these films being appropriate for my project.

The fragments used in this project were selected so as not to contain spoilers, or at least not significant ones. They are from the first episodes of the series they belong to, from the first scenes of a film, or from the first film of a well-known saga. The main purpose of this is not to spoil the films or series for my students, since that might even decrease their motivation or produce some kind of discontent that could affect the session, like raising their affective filter. Krashen (1981) defines the affective filter as an attitude related to second language acquisition, in which “performers with high or strong filters will acquire less of the language directed at them, as less input is ‘allowed in’ to the language-acquisition device” (p. 22). That is, if the learner is stressed, anxious, or in a bad mood it can prevent him or her from learning, which is something to avoid as a teacher. Spoiling some TV series or film that students might have liked to watch at some other moment can negatively affect their mood, and thus their attitude towards the lessons and their disposition to learn.

Table 4 shows the titles compiled with the fragments selected and their exploitation. The first column includes the titles of the films or series from CAMELLS, selected for script analysis. The middle column contains what episode or film from the franchise was chosen (in the case of The da Vinci Code it was left blank, since there is only one film). The last column indicates the fragments analysed and their minutes. Each fragment received a title, with the intention of reflecting the main topic and to make it easier to identify. The titles in bold have been selected to illustrate the two protocols followed for their exploitation in the next section.

Table 4 Titles and Fragments Selected in CAMELLS

| Films or series | Selection for exploitation | Selection of relevant fragments |

|---|---|---|

| Avengers | Iron Man | “Meeting a celebrity” (0:40-3:50) |

| Harry Potter | 1st movie | “A new family” (1:35-4:00) “A disappointing birthday” (4:04-5:55) “Visiting the zoo” (6:00-8:32) “Meeting Hagrid” (12:30-18:22) “Choosing a wand” (24:43-28:45) “You-Know-Who” (28:45-31:00) “Looking for platform 9 –” (31:05-33:55) “New friends” (34:20-37:47) “Welcome to Hogwarts” (39:30-41:27) “The sorting hat” (42:50-46:05) “Nasty Snape” (51:18-53:16) “Flying class” (55:05-59:10) |

| The da Vinci Code | “Cultural relativism” (3:30-5:13) | |

| The Hunger Games | 1st movie | “The president’s speech” (12:50-14:00) “Survival techniques” (26:00-28:36) |

| Friends | Season 5, Ep. 9 Season 10, Ep. 3 |

“Ross’ sandwich” (11:35-13:35) “Fake tan” (4:40-7:12) |

| Peaky Blinders | Season 1, Ep. 1 | “Pub fight” (10:00-14:35) |

| Stranger Things | Season 1, Ep. 1 Season 1, Ep. 2 |

“Dungeons and Dragons” (1:43-4:50) “Will’s whereabouts” (11:08-12:40) “School bullies” (12:50-13:57) “Officer Hopper” (16:15-18:52) “A weird girl” (0:10-4:30) |

Exploitation of CAMELLS

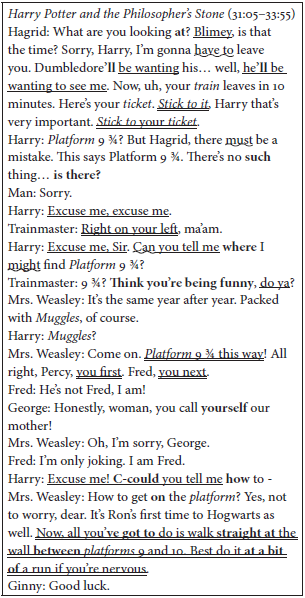

After the compilation of CAMELLS while bearing in mind students’ choices and preferences of films and series, and its analysis in terms of potential uses in the secondary education EFL classroom, the two protocols that can be used for the exploitation of the selected fragments will be illustrated. An example of the corpus lexico-grammatical analysis using the coding system specified in Figure 1 can be found in Figure 2. As can be seen, there is a particular feature that is repeated recurrently-modal verbs-and thus students’ attention, once their comprehension of the fragment has been checked, could be drawn to it, focusing on form (Ellis et al., 2002) as modal verbs are presented in a meaningful, relevant context. Some features could be marked when students are focusing on the comprehension of the message making use of input enhancement strategies (Larsen-Freeman, 2014; Okar & Shahidy, 2019), both using the script or captions when viewing (Pujadas & Muñoz, 2020).

The modal verbs present are for positive deduction (must), prediction (will), permission/request (can, could), obligation (have to/have got to) and possibility (might). The teacher may also have to explain and provide examples of the modals not present in the fragment, like ability, negative deduction, no obligation/necessity, prohibition, and advice. Students could be asked to identify and point out the modal verbs in this fragment, which would help them understand them better and recognize them in future texts. Also, modal verbs could be highlighted to make them salient making use of input enhancement techniques and drawing their attention to them (Larsen-Freeman, 2014; Okar & Shahidy, 2019).

This fragment also has different functions related to the topics it covers, like asking for and giving directions, use of politeness and giving instructions. Because of this, the scene can also be exploited in other ways and used for different lessons. An activity focused on teaching how to give instructions can be combined with teaching modal verbs, since instructions are usually constructed with them (must/mustn’t, need/not need to and have/not have to will probably be used for this purpose). This may also be the case with an activity focused on politeness (asking for things politely, like Harry does in this scene; could, may, might, and will are probably going to be used). Aside from the modal verbs and the topics mentioned, the character of Hagrid speaks with a West-country English accent and uses rustic expressions, like “will be wanting to see me.” This may be useful for the EFL classroom as an example of English accents and expressions different from the “standard” usually present in the EFL course books. Some useful vocabulary has been highlighted, as well as a collocation (“stick to it”), which can also be learnt from audiovisual input and which are important for students to know (Puimège & Peters, 2020).

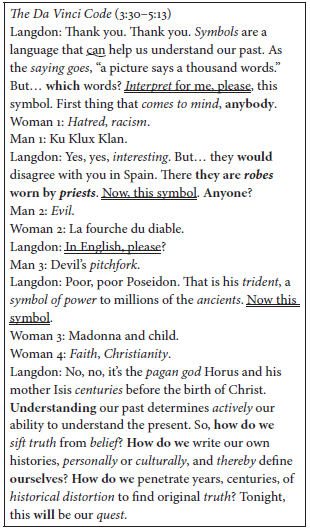

Whereas in the example in Figure 2 a particular grammatical feature stood out, in other fragments selected in CAMELLS, that may not be the case (see Figure 3). In this case the exploitation is based on the fragment’s meaning and content to a greater extent.

This is a good scene with which to talk about the topic of symbolism and cultures with students. This fragment focuses mostly on vocabulary (mainly racism, religion, mythology, and pop culture) and the grammar present is quite simple and within fourth-year students’ level (it is limited to how-questions, that-relative clauses, present simple and continuous, and demands), so in this case it may be more interesting and beneficial for students that the activities have a focus on meaning. The scene is very versatile; the activities arising from it could focus on current symbolism, that is, new language (like emojis and memes, which students will be familiar with), but also on the idea of multiculturalism and the relativity of images depending on how and where one has been brought up. Students could be asked to give their opinions and to write messages making use of those new ways of expressing meaning these days.

It could also be useful for cross-curricular activities or projects, since it can be easily related to subjects such as history (with the theme of the Ku Klux Klan and the robes used in the Easter celebrations in Spain), art and literature (the images of Poseidon and Isis). Although this suggestion is not related to the main EFL activities proposal, it could be interesting to relate the English language classes to other subjects to motivate students and help them associate concepts, since many things that are taught in school should not be seen in isolation if the objective is to promote better understanding.

When checking the different fragments analysed for exploitation, I found that it is very difficult to find one that focuses on only one or two linguistic items (either lexical, syntactic, or grammatical items) as is the case of the example in Figure 2. There tends to be variety in the use of the language, as films and series usually attempt to mimic real-life situations and conversations, and people do not normally use just one tense or type of adverb (for instance) when communicating. Regarding the subject matters of the fragments, initially many of the themes in the analysed fragments were similar. For instance, several examples of instruction-giving and commands were found (in Stranger Things, Friends, and various scenes of Harry Potter), as well as the theme of bullying (Harry Potter, Stranger Things). However, the fragments can be exploited in different ways-mainly because some of them do not cover just one topic, and because one can choose to put the focus of an activity on either form or meaning. In any case, students would be exposed to authentic uses of the language and would be having an active role responding and working with it, fostering their communicative competence in the English language.

Conclusion

Secondary education EFL students nowadays are constantly surrounded by AM through the media, and teachers are starting to include these in their lessons as a means of motivation and presentation of authentic language. Taking this into account, a corpus of audiovisual titles and fragments (CAMELLS) was proposed. Apart from keeping learners engaged in the lessons, this corpus could promote effective learning of the English language by developing their communicative and comprehension skills. The process of the creation of CAMELLS was explained, which took into account learners’ opinions on the titles used as well as their impressions on their EFL class practices. AM, in addition to intrinsically attracting students, are a source of authentic language models and clear contexts for better comprehension. CAMELLS was thus constructed by carrying out a survey regarding students’ preferred titles. However, in order to improve EFL students’ communicative competence, appropriate activities for each fragment in line with communicative language teaching principles should be carried out. By studying the scripts through a coding system, one is able to determine which fragments would be most useful for each academic year, regarding either the topics or the lexico-grammatical features available. Additionally, a second survey revealed that secondary education students demanded a more active role in their EFL lessons, with more interactive activities and a higher use of AM, which should also be considered in their exploitation.

My study presents some limitations. First, the number of students that participated in both surveys can be considered low and were restricted to a very particular context. The titles and fragments in CAMELLS were chosen taking into account responses of participants in the fourth year of secondary education, and the analysis of fragments was also done taking the curriculum of this year into account. It would be a good idea to expand CAMELLS for it to include titles and fragments suitable for every year of secondary education. Another limitation is that the activities proposed have not actually been implemented and evaluated for an EFL lesson.

As some future lines of research, the fragments proposed should be implemented in the secondary education EFL classroom, along with suitable activities, in order to verify the actual effect of their use on the learners’ language learning and communicative competence development. It would also be important to take into account students’ level of satisfaction with this procedure, since this is also a crucial aspect to ensure language acquisition. Moreover, there is an aim to expand CAMELLS-since, as mentioned earlier, the one presented in this paper should be considered a pilot version-and to make it more encompassing, addressing every grade of secondary education.