Introduction

English is the most taught foreign language in Mexico, which in turn has forced both public and private institutions to make English as a foreign language (EFL) courses available in various modalities of instruction. Online courses became particularly popular due to the time and space constraints they can help surpass. In the particular case of a public university in southeast Mexico, online courses are available for the two compulsory basic English levels undergraduate students have to take as part of their bachelor’s degree programs. However, online EFL courses have been found to be the most criticized modality of instruction within that institution, being two of the biggest problems the online course design and the support provided to students (Herrera-Díaz & González-Miy, 2017; Ocampo-Gómez & González-Gaudiano, 2016). Within the official course curriculum, the ultimate goal of all compulsory English courses within this university is for students to be able to engage in meaningful communication in this foreign language (Sampieri-Croda & Moreno-Anota, 2015). However, according to the work of multiple linguists over the last decades (Bachman, 1995; Canale & Swain, 1980; Council of Europe, 2001; Hymes, 1972; Nguyen & Le, 2013; Sanhueza-Jara & Burdiles-Fernández, 2012), being able to engage in communication is related to the development of learners’ communicative competence, which seems not to be happening in the context where our study took place.

Based on the abovementioned authors, this competence is defined within this paper as the use individuals make of their grammatical knowledge of morphology, phonology, and syntax, as well as their social knowledge to exchange information and negotiate meaning in communication. Nevertheless, as mentioned before, upon analyzing the compulsory online English courses at the university under study, the disarticulation between the course goals, instruction, and assessment also seemed evident. On the one hand, the current instructional design fosters little interaction between participants and instructor in the target language. That is to say, students are not exposed to language models that allow them to actually learn the language according to the principles of the teaching approach used in other modalities (the communicative language teaching [CLT] approach).

It is also possible to argue that without input in the target language (activity instructions, examples and explanations are usually presented in Spanish), students are not likely to be able to go through all three stages of the interaction hypothesis, which purports to explain how the learning of a language occurs (Ellis, 1991, 2008; Gass & Mackey, 2007; Ghaemi & Salehi, 2014). The stages in the interaction hypothesis, according to Ellis (1991), are described as follows: (a) noticing, the individual perceives and is aware of the linguistic characteristics of the input he or she is receiving through interaction; (b) comparison, the individual compares the characteristics of the input with that of his or her own spoken output; (c) integration, the individual constructs his or her own linguistic knowledge, thanks to the two previous elements, and internalizes it. Therefore, if online instruction does not provide students with interaction and enough language models, it would be nearly impossible for them to build their own language. That is, we would be expecting students to communicate in the language without providing them with the tools to do so.

Assessment, on the other hand, is standardized for all modalities of instruction. This means that those students enrolled in the online version of the courses are expected to take communicative oral tests at the end of the course even if they were not given the chance to ever interact orally with their classmates in the target language prior to the test. Moreover, these oral assessments are provided to online course students in a traditional face-to-face setting, disregarding the technology-based nature of the course itself. So far, the institution has not shown any real interest in delivering oral assessment in a way that is congruent to the principles of online courses, which, in turn, could be discouraging teachers from pursuing it as well. Nevertheless, according to the principles of CLT, instructional design, and assessment of communication, it seems evident that both the technological and pedagogical aspects of the course can be improved so as to provide students with a real opportunity of developing communicative competence in these online courses.

Consequently, this educational intervention aimed at improving the techno-pedagogical design of the second level of the compulsory EFL online courses within this Mexican university. According to Coll et al. (2008), the term techno-pedagogical emphasizes the two dimensions of instructional design for courses supported by technology: (a) the technological, concerned with the tools and resources to be applied within the learning environment; and (b) the pedagogical, which has to consider students’ characteristics and needs, as well as the learning objectives and competences to be achieved. The modifications made to the English II online course were based on the RASE (Resources, Activities, Support, Evaluation) techno-pedagogical model, proposed by Churchill et al. (2013), as well as on the CLT approach, as described by Larsen-Freeman and Anderson (2012).

The four components tackled by the RASE model were modified and enriched following not only its own proposed principles (Churchill et al., 2013), but also disciplinary principles for language teaching and learning. Both the RASE model and the CLT approach are based on constructivism, which made their integration unproblematic. As a matter of fact, both of them regard evaluation and assessment as a task or series of tasks that must relate and be similar in nature to the resources and activities students were exposed to throughout the course (Churchill et al., 2013; Larsen-Freeman & Anderson, 2012). Therefore, online synchronous interaction in the target language among participants and online assessment can work together to achieve the course’s goal: have students develop the skills and competence they need to communicate in English through the exchange of information and negotiation of meaning.

It is worth mentioning that the present article is focused on the fourth component of the RASE model: Evaluation, that is, communicative assessment online, as was provided to students in the aforementioned English II online course. Therefore, the objectives that guided the study, with regard to evaluation, were:

To describe how communicative assessment can be implemented online following the same disciplinary and institutional principles applied in face-to-face assessment.

To determine whether the provision of synchronous contextualized oral practice influences the students’ communicative competence.

Literature Review

Understanding the Concept of Communicative Competence

Hymes (1972) coined the term communicative competence relating it to the importance of learning not only what is grammatically correct but also what is appropriate. Although Hymes’ work was not originally created in relation to learning foreign languages, it led linguists such as Canale and Swain (1980) and Savignon (1983) to reassess the original definition, determining that this competence must be observable in communicative acts. These authors also identified the need to look for ways to contribute to the development of communicative competence, as well as their evaluation since they considered it measurable. Several other authors (Bachman, 1995; Council of Europe, 2001; Pilleux, 2001; Sanhueza-Jara & Burdiles-Fernández, 2012; Widdowson, 1983) have laid the foundations for the development of new techniques, methods, and approaches to teaching/learning languages, as well as for the evaluation of communication.

The Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) for learning, teaching, and language assessment (Council of Europe, 2001, 2018) provides one of the most accepted descriptions of communicative competence based on “different competence models developed in applied linguistics since the early 1980s” (Council of Europe, 2018, p. 130). Drawing from the work of the authors mentioned in this section, it is possible to distinguish at least three dimensions of communicative competence: linguistic competence, pragmatic competence, and sociolinguistic competence, each of which can be studied through certain indicators (see Table 1).

Table 1 Dimensions and Indicators of Communicative Competence

| Dimension | Definition | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Linguistic competence | Use an individual gives to his or her grammatical, lexical, and phonological or spelling knowledge (depending on the means or modality of the communication). |

|

| Pragmatic competence | Communicative use of the language that is consistent and appropriate according to the function or need that the individual intends to fulfill when interacting in the target language. |

|

| Sociolinguistic competence | Appropriate use of linguistic and pragmatic competences according to the context in which communication takes place. |

|

The introduction of methodologies and approaches aimed at communicative learning and assessment of a language in order to reflect the components of the so-called communicative competence was nothing less than revolutionary (Savignon, 2017). Following the work carried out by Savignon (1983) almost five decades ago, one could see it was demonstrated that grammatical accuracy (related to linguistic competence) could be developed to the same degree in groups that had had communication-focused practice and in groups that had not been exposed to that type of practice; however, it would be the groups exposed to the communicative practice that would show greater mastery of the foreign language when exposed to different communicative situations (Savignon, 2017). Therefore, communication is essential to both the teaching and assessment of students’ communicative competence because during communication the use of all three components of this competence are evidenced.

In this study, communication is understood as: “The exchange and negotiation of information between at least two individuals with the use of verbal and nonverbal symbols, oral and written/visual models, and the production and comprehension processes” (Canale, 1983, p. 4). Communicative competence is, then, reflected during the communication and interaction between individuals through the use of linguistic components (linguistic competence), combined with a consistent and adequate use, according to the function or need that the individual intends to fulfill/satisfy (pragmatic competence), and according to the social context in which the communication takes place (sociolinguistic competence).

Principles for the Assessment of Students’ Communicative Competence

The CEFR provides guidelines for the teaching, learning, and, perhaps most importantly, assessment of communication skills in foreign languages. According to the CEFR, it is of utmost importance that an assessment procedure be practical (Council of Europe, 2001). This relates to the fact that assessors only see a limited sample of the language the student is able to produce, and they must use that sample to assess a limited number of descriptors or categories in a limited time. What this means is that if we were trying to assess all indicators of all three dimensions of students’ communicative competence, the procedure would not be practical, and it might not be feasible due to time constraints while carrying out the assessment. Moreover, the Council of Europe (2001), through their CEFR, establishes that oral assessment procedures “generalize about proficiency from performance in a range of discourse styles considered to be relevant to the learning context and needs of the learners” (p. 187). Therefore, an oral assessment procedure should keep some relation to certain needs and situations speakers of a language face in real life.

The CEFR also addresses the subjective nature of the grades awarded to students. Grading of direct oral performance is awarded on the basis of a judgment, which means assessors decide how well a student performed taking into account a list of factors or indicators. These decisions are usually guided by a pre-established set of guidelines which is usually nurtured by the assessors’ own experience. Nevertheless, the advantage of this subjective approach is that it acknowledges “that language and communication are very complex, do not lend themselves to atomization and are greater than the sum of their parts” (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 188). In other words, guided-judgement-based assessment is a fit solution to a complex issue, especially since the subjective factor can be controlled through the use of a clear set of criteria or guidelines to use for the assessment, and the undertaking of training on how to use said criteria.

Another key issue to the assessment of oral performance is what to assess. When attempting to assess students’ communicative competence, it would seem obvious to measure each of the indicators shown in Table 1, in the previous section. However, a set of eleven indicators would reduce the practicality factor an oral assessment procedure is supposed to keep. In consequence, the CEFR advises that indicators should be combined, reduced, and even renamed into a smaller set of criteria deemed appropriate to the needs of learners and the requirements of the task. According to the Council of Europe (2001), the resulting criteria could be awarded the same weight or not, depending on whether certain factors are considered more crucial than others. Here we could even propose that when assessing communicative competence, it is important to find a balance between form (represented by the linguistic competences) and use (related to the pragmatic and sociolinguistic competences).

We could argue that finding this balance in indicators of form and use relate to the original tenets of Hymes (1972) and would thus help assess whether students have learned what is grammatically correct and can use it appropriately. In consequence, an instrument to measure three indicators that represent form and three that represent use was designed to be used as part of this intervention, and it will be described in the Method section. The guidelines provided by the CEFR, in addition to those by authors such as Brown (2005) and Fulcher and Davidson (2007), allow the development of communication-oriented tests which can also be referred to as communicative tests. In this regard, Brown indicates five characteristics that a test must have to be considered communicative: (a) the use of authentic situations, (b) the production of creative language, (c) significant communication, (d) integrated language skills, and (e) unpredictable language input. Bakhsh (2016) adds that communicative tests differ from other language tests in that they intend to predict how students would react in a real communicative situation. Facing real communication situations involves the integrated use of language skills. The effectiveness of communication will depend on the extent to which the conversation helps students meet the fictitious needs assigned to them in the communicative test.

Method

Context of the Study

As has been previously mentioned, oral assessment of the target language, within the higher education institution where the study was carried out, follows the same standardized procedures regardless of the modality of instruction. This means students from blended, autonomous, and online courses are expected to undergo the same oral assessment procedure as those who have received 90 hours of instruction and practice of the language in a traditional face-to-face setting. Nevertheless, under the current instructional design of online English courses, students never communicate orally in the target language prior to the oral assessment.

All students enrolled in any of the compulsory English courses are assessed at least twice to determine their oral performance in the language: the first time (partial exam) around the eighth week of the course and the second (final exam) after the sixteenth week. Even though there is a written counterpart to the oral assessment procedure, the oral test seems to be more challenging for students even when enrolled in a traditional face-to-face course. The oral performance is assessed in pairs or trios, during two tasks, the first of which is individual with the instructor asking each candidate a set of personal questions related to heretofore covered language points or topics. The second task is carried out in pairs or trios, and demands for the participants to engage in an unplanned conversation, which, as previously stated, the students had never been prepared for. This conversation must emerge from a communicative situation they are provided with on a card.

The communicative-situation cards contain the description of a fictitious situation and a list of language prompts they can use to create questions around that situation. According to several authors (Bakhsh, 2016; Brown, 2005; Fulcher & Davidson, 2007), these kinds of tasks fit within the definition of a communicative test because they try to predict how students would react in a real-life communicative situation. That is the main reason why the institution where the intervention took place gives the same oral tests to all students, regardless of the modality under which they take the course, because the aim is to determine how effectively students can communicate in (semi)authentic situations.

During the oral assessment procedure, the assessor listens and grades concurrently. Assessors grade two areas, form and communication, thus assigning two scores for each task. Even when these two areas are the ones we mentioned in the previous section in relation to the tenets of Hymes (1972)-what is grammatically correct and what is appropriate-we can now argue that including only two indicators for each task might oversimplify what we have already established as a complex issue: communication. Not providing enough indicators could lead to subjectivity issues the CEFR warns about. The oral assessment procedure described in the present section is always carried out in a face-to-face setting, which means that students, who study English online during the whole semester, are required to meet their teachers/online instructors at the Language Center facilities. By not finding ways to arrange online assessment, the whole purpose of allowing students to benefit from a modality of instruction that avoids time and space constraints is partially defeated.

Using a Web Conferencing Tool for Communicative Assessment

The intervention carried out in the present study aligned the four elements of the RASE model (Resources, Activities, Support and Evaluation) through the use of contextualized explanations and group practice (guided by the instructor), synchronous peer interaction (through online interactive resources and activities), as well as oral assessment (through a web conferencing tool). In other words, students in the experimental group were provided with explanations, resources, and opportunities to use the language in contextualized situations (e.g., plans after they graduate, directions around the campus, previous vacations), and they were evaluated accordingly. It must be said that both the activities and the evaluation were administered on the web conferencing tool.

During the investigation, students were assessed three times, which means an additional assessment moment was added to the two that usually take place, as described above. That is to say, students were required to meet their English instructor before the official start of the course in order to take a pre-test and sign the corresponding consent forms. This first assessment (pre-test) used the contents from the previous course, English I, and sought to gather information on students’ oral performance before the intervention. Both the experimental and control groups took the pre-test under identical circumstances (see the composition of the groups in the Design of the Study section). As a matter of fact, the groups were mixed during the procedure and no distinction was made in regard to which group participants belonged to until after the data had been recorded in the corresponding grid.

After the pre-test, over the next two assessment moments (one control test and a post-intervention test), the oral assessment procedures were carried out completely online for the experimental group (EG). This implied first and foremost a change in the setting, but it also helped make schedules more flexible and accessible to students. In other words, assessing students’ oral performance online allowed them to avoid time and space constraints in the same way online courses work.

The oral assessment was carried out via the Zoom platform, and each online session involved four participants: a pair of students, the course instructor, and an assistant teacher. Only when both students were online, did the instructor open his microphone and started delivering instructions. The nature of the tasks during the control test did not change from the face-to-face counterpart; there were still two: (a) an individual task where the instructor asked the students personal questions based on the contents of the corresponding units; and (b) a joined communicative task, where the students were presented with a communicative situation for which they had to interact with each other, asking and answering questions to fulfill a fictitious need.

The delivery of task instructions slightly changed for the second task, as students listened to the instructions instead of reading them on a situation card. While the instructor read the situation and instructions to them, the assistant teacher typed the same instructions in the chat section and delivered them to each student individually (in private chat messages) in case they needed support. In sum, the main difference in the assessment procedure for the second task was the method of delivery of instructions: no situation cards but oral instructions/prompts for the assigned communicative situation, and the fact that the students were not provided with prompt words like the ones found on the communicative situation cards handed out in face-to-face settings.

The tasks in the post-intervention test were slightly changed, but still complied with what was established in the program for the online English II course: a final project presentation in which students were asked to prepare a short presentation they delivered orally during a synchronous web conferencing session. This assessment procedure consisted of two tasks: (a) presenting information they had a chance to plan in detail in relation to some key topics of the course (talking about past experiences, family, future plans, hobbies, etc.); and (b) answering non-planned questions the instructor and the assistant teacher asked regarding the information they had just presented. The second task was given particular attention because it involved the spontaneous production of language and the use of integrated language skills (listening to some of the questions and reading some others in the chat), while talking about their own life and experiences. Therefore, this new oral assessment procedure still complied with the key characteristics of a communicative test as described by Brown (2005).

Grades were recorded in the same way they would be if the assessments had been applied face-to-face; that is to say, the assessor (course instructor) assigned them concurrently as the students performed using what could be considered guided judgement. Instead of simply assessing form and communication as in the institutional scoring grid, the assessor used a new instrument that assessed six areas or indicators of the three dimensions involved in communicative competence. The instrument was specifically designed for this study and will be described in the next section.

Design of the Study

This study follows a quasi-experimental design that uses two groups (experimental and control) and three data collection moments. This kind of design aims to test a hypothesis by manipulating at least one independent variable in contexts where random sampling is not possible (Fernández-García et al., 2014). The variable to be manipulated was the instructional design of an online English II course. As explained previously, the course followed the principles of the RASE model and of the CLT approach. According to different authors (Campbell & Stanley, 2011; Fraenkel et al., 2012), a design with these characteristics gains certainty in the interpretation of its results due to the multiple measurements made. The 221 students enrolled in the online course during the 2019 spring semester across the five regions of the university constituted the target population of the study; whereas, the accessible population was constituted by the 46 students enrolled in said course in the Veracruz-Boca del Río region over the same period of time.

Students enrolled in these online English courses usually have diverse backgrounds in regard to their previous educational experiences studying the language. However, a characteristic they all have in common is having validated or credited the previous course or level (English I). Students in the accessible population belonged to 21 different degree programs. The 46 students taking the course were divided into two groups: experimental (EG) and control (CG). However, the final sample was constituted by the 17 students who were active in the EG and the 13 who were active in the CG. For this intervention, as part of the changes made to the instructional design regarding the second component of the RASE model (Activities), the students in the EG were asked to join web conferencing sessions where they received contextualized instruction as well as interactive oral and written practice in the target language. To achieve this, the students used their microphones and the chat capabilities of the web conferencing platform Zoom, where the oral assessment of the language also took place. The CG, for their part, took the online course under the original instructional design and conditions, that is, they followed the course remotely with no opportunities for peer-on-peer interaction, and were then assessed in individual face-to-face sessions with the instructor.

Assessment Instrument

An assessment grid was designed to record the scores obtained by the EG students in the two communicative tasks they were to complete as part of the pre-test procedure. The design of the grid took into account the guidelines and examples offered by the CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001). The operationalization of the communicative competence variable into dimensions and indicators (see Table 1) was also considered in the creation of this instrument, and it was based on the literature presented in the Literature Review section. Six aspects were included, three of which were related to linguistic competence and the other three to pragmatic and sociolinguistic competences, to balance form and use. The aspects originally included in the oral assessment grid were: (a) accuracy and lexical and grammatical control; (b) lexical and grammatical range; (c) pronunciation; (d) style and register; (e) fluency, coherence, and cohesion; and (f) contextual property. In agreement with the ideas of Leung (2005), these indicators allowed assessors to consider not only standard English, but also what we may call a local variety of the target language. That is to say, the students were expected to perform as effective users of the target language during their assessment process, with no consideration for specific accents.

The grid uses a scale from 1 to 5 (5 being the maximum score for each aspect), resulting in a score of 5 to 30 points. In order to determine the validity of the instrument, two procedures were followed. The first consisted of a workshop where three experts in teaching EFL, all of which had previous experience working with online English II groups within the institution, emulated the process originally followed for the design of the grid. As a result of that workshop, it was decided that cohesion should not be assessed in the oral performance of students of such a basic level, since their utterances are usually short. The second procedure for testing the validity of the instrument was expert evaluation. A different group of experts was asked to evaluate the coherence and relevance of each aspect included in the grid, specifically in relation to the measurement of students’ communicative competence. The experts scored each indicator using a format proposed by Escobar-Pérez and Cuervo-Martínez (2008), which resulted in the V of Aiken coefficient shown in Table 2.

Table 2 V of Aiken Coefficient

| Linguistic competence | Pragmatic competence | Sociolinguistic competence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect 1 | Aspect 2 | Aspect 3 | Aspect 4 | Aspect 5 | Aspect 6 | ||||||

| Coh | Rel | Coh | Rel | Coh | Rel | Coh | Rel | Coh | Rel | Coh | Rel |

| 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.96 | 0.75 | ||||||

| 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.75 | |||||||||

| 0.88 | |||||||||||

Note. Coh = coherence, Rel = relevance.

Due to the subjective quality of the instrument, product of the guided judgement required to use it, two assessors tested the scoring agreement as a means to ensure its reliability. Having two oral examiners, or assessors, is not only common but also recommended in certain institutions, due to the fact that two different interpretations of the qualification criteria can balance each other, leading to the advantage of impartiality when assessing (Sun, 2014). Eleven students (apart from the 46 participants of this study) were assessed in two communicative tasks at the end of an online English course at the institution where the study was conducted. Nine students received identical or very similar scores, and two received scores with drastically different results. The results of the pilot test to determine scoring agreement in relation to the reliability of the instrument show an agreement at an acceptable level in line with the principles established by Fraenkel et al. (2012).

Data Analysis

In order to determine how students’ communicative competence had developed over the 16 weeks the course lasted, students were assessed three times. Students from both the EG and the CG were given an oral pre-test in a traditional face-to-face setting before the online course started. Afterwards, two oral assessment procedures were carried out online on the web conferencing tool called Zoom with the EG, and the members of this group were scored using the grid described in the previous section. The same grid was used with the CG, which was following the traditional assessment procedure. The data analysis followed the four stages proposed by Creswell (2015): data processing, basic analysis, advanced analysis, and in-depth analysis. During the first two stages, the scores originally registered in the grid were transcribed into a database in SPSS®, which was repeatedly cleaned. As part of the advanced analysis, the mean scores of each group were obtained and contrasted. The descriptive statistics were also obtained as per the indications of Creswell and Guetterman (2019). In the final stage, a Shapiro-Wilk normality test was run and contrasted against Q-Q plots. The reasoning behind choosing the Shapiro-Wilk test is that it is suitable for small sample sizes (Pedrosa et al., 2014; Razali & Wah, 2011) such as the one reported in this article.

Once the data were proved to have a normal distribution for all three oral assessment moments, the conditions for a repeated measures test established by Ho (2006) and Pituch and Stevens (2016) were verified and the aforementioned test was carried out.

Results

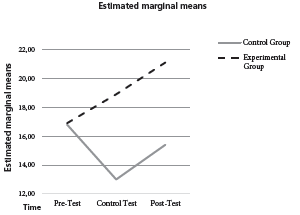

As can be observed in Table 3, the average scores the EG obtained when measuring its members’ oral communicative competence increased steadily from the first to the third oral assessment procedure. However, the average scores for the CG decreased from the first to the second test and increased again on the third test.

Table 3 Mean Communicative Competence Scores of the Experimental (EG) and Control Groups (CG)

| EG | CG | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | 17.20 | 18.00 |

| Control test | 19.50 | 13.67 |

| Post-intervention test | 20.21 | 17.23 |

Even though the CG managed to recover from the second to the third assessment moment, the mean score they obtained in the post-intervention test was still almost three points below the one of the EG. A possible cause for the fall of their communicative competence mean score from the first to the second moment, in particular when compared to the scores obtained by the EG, could be the fact that the control test for English II (for both groups) covers a language point that is typically regarded as challenging for students: the simple past tense. Although the mean scores obtained by the EG showed a better oral performance and thus a more developed communicative competence, this result was further confirmed as a product of the modifications to the instructional design through the use of a statistical test.

Based on the number of measurements made across time, as well as on the fact that we had two groups, a repeated measures test was selected to determine whether the mean scores obtained by the groups were or were not related to the treatment. Nevertheless, a number of conditions needed to be met before running such a test (Pituch & Stevens, 2016), namely:

Independence of the observations: Since the oral assessment involved interaction between participants (specifically in Task 2), we acknowledge that, just like in any other study that involves interaction, students might have influenced each other’s performance.

Multivariate normality: Proved through a Shapiro-Wilk test.

Sphericity or circularity and homogeneity of covariance matrixes: Due to lost data from those participants who either joined the course late or missed one of the assessment procedures. The group size proportion changed from 1.3 (given that the 17 students from the EG and the 13 from the CG had taken three tests), to 2.0 (since only 10 of the students from the EG and 5 from the CG took all three tests), it was necessary to run Mauchly’s sphericity test.

The Shapiro-Wilk test and the Q-Q plots showed the data distribution could be considered normal. Besides, the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test show a p value greater than 0.05, thus proving the data meet the criteria of normality (see Table 4).

Table 4 Normality Test

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov a | Shapiro-Wilk | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Sig | Statistic | df | Sig | |

| Pre-test | 0.151 | 15 | .200* | .965 | 15 | .777 |

| Control test | 0.90 | 15 | .200* | .953 | 15 | .577 |

| Post-intervention test | 0.106 | 15 | .200* | .969 | 15 | .835 |

a Lilliefors significance correction.

*This is a lower bound of the true significance.

The data were also tested with the help of a Mauchly’s test where a p value of 0.459 proved sphericity, one of the essential conditions to be met before executing a repeated measures test (Ho, 2006; Pituch & Stevens, 2016). When executing the repeated measures test, it was determined that, although there were significant differences in students’ oral communicative competence throughout the implementation, those differences were not equivalent for the EG and CG. Consequently, an additional test was run in order to determine if the interaction of the between-subjects factor (the group where they were placed) and the within-subjects factor (the repeated measures) had been significant. To achieve this, the coding of the repeated measures test was modified on SPSS as follows:

DATASET ACTIVATE ConjuntoDatos1.

GLM PTccoral TCccoral PostTccoral BY group

/WSFACTOR= time 3 Polynomial

/METHOD= SSTYPE(3)

/PLOT=PROFILE(time*group)TYPE=LINE ERRORBAR=NO MEANREFERENCE=NO YAXIS=AUTO

/EMMEANS=TABLES(time) COMPARE ADJ(BONFERRONI)

/EMMEANS=TABLES(group*time) COMPARE (group) COMPARE ADJ(BONFERRONI)

/EMMEANS=TABLES(group*time) COMPARE (time) COMPARE ADJ(BONFERRONI)

/PRINT=DESCRIPTIVE ETASQ OPOWER HOMOGENEITY

/CRITERIA= ALPHA(0.5)

/WSDESIGN= time

/DESIGN=group

Upon execution of the new command, it was determined that the differences between the communicative competence demonstrated by the groups in the pre-test were not statistically significant (p = 0.979). Nevertheless, the time-pair comparisons showed that the differences in students’ communicative competence across time were statistically significant exclusively for the EG (p = 0.031) between the first and the final assessment moments. The same was not true for the CG (p = 0.255). The changes in mean scores across time are summarized in Figure 1.

Based on the results obtained and described in this section, it is possible to attribute the improvement in the EG’s communicative competence between the first and the third oral assessment procedures to the intervention in which said group was provided with synchronous contextualized practice in the target language and oral assessment on a web conferencing tool. This was carried out in agreement with the modifications and alignment of the elements of the RASE model.

Conclusions

Assessing students’ oral communicative competence online is not usually pursued within the institution where this study took place. However, in relation to the first research objective, we can assert that online assessment was feasible, mainly thanks to the use of a web conferencing platform students found easy to use, and the support of an experienced instructor. Thus, it has been proved that not only is online evaluation of students’ oral performance commendable, but also successful when its execution is carefully planned. This study also found that it was possible for assessors to deliver instructions, and for students to perform communicative tasks aligned with the principles of oral assessment and communicative tests established by several English language teaching authors (Bakhsh, 2016; Brown, 2005; Council of Europe, 2001; Fulcher & Davidson, 2007).

Students who took the oral online assessment through the web conferencing tool (Zoom) did not experience any major inconveniences and were able to perform as they normally would in a face-to-face setting. One of the clear advantages of using this web conferencing platform, instead of having students meet their instructor in person within a limited timeframe, was the feasibility to align the elements of the RASE model and have the evaluation process become congruent with the online modality of the course. In line with the recommendations provided by Sandoval-Sánchez and Cruz-Ramos (2018), a second instructor or assistant can help with technical aspects as well as with the delivery of instructions, thus improving the quality of the experience for students. The assistant was always ready to help students with backup questions that might escape the main instructor when carrying out the oral assessment procedures on a web conferencing platform.

Regarding the second research objective, the study also proved that the EG’s communicative competence improved steadily from the beginning to the end of the implementation, and this improvement was a product of the changes made to the instructional design of the English II course. This also helps highlight the importance of aligning resources, activities, support, and evaluation when dealing with a language course online. Moreover, we could argue that students who were enrolled in the EG were able to cope with new, and sometimes challenging, language points better than their CG counterparts during assessment.

It must be mentioned that we found some limitations of the study, such as having a small sample chosen non randomly, the possible existence of extraneous variables, and the lack of independent statistical analysis for each dimension of the communicative competence. Accordingly, we may suggest further research on the same topic but by including more groups of online English courses within the same institution or any other with similar characteristics; studying each dimension separately as well as the communicative competence as a whole; identifying those variables, besides the ones related to the instructional design, that may affect the intervention as well as the results.

We hope the present manuscript encourages teachers, online instructors, and institutions to embrace the capabilities of online language courses by providing online assessment options that are truly congruent with the principles of online instruction.